Abstract

Reductions in mesolimbic responsivity have been noted following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB; Ochner et al., 2011a). Given potential for postoperative increases in postprandial gut (satiety) peptides to affect mesolimbic neural responsivity, we hypothesized that: 1) post RYGB changes in mesolimbic responsivity would be greater in the fed relative to the fasted state and; 2) fasted vs. fed state differences in mesolimbic responsivity would be greater post- relative to pre- surgery. fMRI was used to asses neural responsivity to high- and low-calorie food cues in five women 1mo pre- and 1mo post-RYGB. Scans were repeated in fasted and fed states. Significant post RYGB decreases in the insula, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) responsivity were found in the fasted state. These changes were larger than neural changes in the fed state, which were non-significant. Preoperatively, fasted vs. fed differences in neural responsivity were greater in the precuneus, with large but nonsignificant clusters in the vmPFC and dlPFC. Postoperatively, however, no fasted vs. fed differences in neural responsivity were noted. Results were opposite to that predicted and appear inconsistent with the initial hypothesis that postoperative increases in postprandial gut peptides are the primary driver of postoperative changes in neural responsivity.

Keywords: RYGB, Roux, Obese, fMRI, Bariatric

Introduction

Research on the neural control of food intake suggests that reward-related mesolimbic responsivity to food cues may be a primary driver of food intake (Berthoud & Morrison, 2008; Stoeckel et al., 2008). Such reward-driven overconsumption continues despite homeostatic (i.e., hypothalamic) and inhibitory (i.e., dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [dlPFC]1) neural signaling designed to maintain energy balance and prevent excess weight gain (Berthoud & Morrison, 2008). We recently reported significant reductions in reward-related (e.g., striatal) and inhibitory (dlPFC) mesolimbic neural responsivity to palatable food cues from pre to post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery in obese women tested postprandially (Ochner et al., 2011a). These data suggest a possible neural mechanism for the significant proportion of post RYGB weight loss left unexplained by the restrictive and malabsorptive mechanisms of the procedure (Ochner et al., 2011b). In addition, these findings raise the question of what may be driving post RYGB changes in neural responsivity.

Gut peptides have been shown to influence neural signaling, both peripherally and centrally (Berthoud & Morrison, 2008; Moran and Dailey, 2011), suggesting the possibility that postoperative changes in gut peptide signals may be driving postoperative changes in neural signaling. Large changes in postprandial satiety-inducing gut peptides (e.g., peptide YY3-36 [PYY3-36] and glucagon-like Peptide-1 [GLP-1]) have been consistently noted following RYGB (Bose et al. 2010; Ochner et al. 2011b). However only small changes in fasting hormones (e.g., ghrelin) have been reported (Ochner et al., 2011b; Bose et al., 2010). Given their potential to affect neural signaling (Berthoud & Morrison, 2008), we asserted that the dramatic postoperative increases in postprandial levels of these satiety hormones may be driving the decreases in postprandial ratings of desire to eat and reward-related mesolimbic neural responsivity noted in our prior report. With larger post RYGB changes in postprandial (fed state) vs. preprandial (fasting state) gut peptides it was reasoned that, if postoperative changes in postprandial gut peptides were the primary driver of postoperative changes in neural responsivity, larger postoperative changes in neural responsivity would be noted in participants assessed in a fed relative to a fasted state. Stated simply, there are larger postoperative changes in gut peptides in the fed vs. fasted state. Thus, if those changes in gut peptides were mainly driving neural changes, we would also expect to see larger neural changes in the fed vs. fasted state.

Prior to RYGB, levels of the postprandial gut peptides PYY3-36 and GLP-1 rise following a meal, presumably triggering satiety signals in the brain. Post vs. Pre RYGB, a much larger spike in these peptides is seen following meal ingestion, potentially due to faster gastric emptying resulting from the reduced postoperative pouch size and bypassing of a portion of the upper intestine with the gastric bypass procedure (Ochner et al., 2011b; Bose et al., 2010). More rapid transit of nutrients through the lower gut may stimulate a faster and enhanced postprandial release of gut peptides, and enhance the effect of the ileal break mechanism (Cummings et al., 2004; Ochner et al., 2011b). The enhanced postprandial release of PYY3-36 and GLP-1 after RYGB may trigger neural satiety pathways and contribute to post RYGB weight loss (Moran and Dailey, 2011; Ashrafian and le Roux, 2009). Thus, there are relatively small but reliable differences between fasted and fed levels of PYY3-36 and GLP-1 prior to RYGB and very large differences between fasted and fed levels of these hormones following RYGB. Given the larger post vs. pre RYGB differences between fasting and fed levels of PYY3-36 and GLP-1 it was reasoned that, if postoperative changes in these postprandial gut peptides were the primary driver of postoperative changes in neural responsivity, larger fasted vs. fed state differences in neural responsivity would be observed post relative to pre surgery. Again stated simply, there are larger fasted vs. fed differences in gut peptides before (vs. after) surgery. Thus, if gut peptides were mainly driving neural responsivity, we would also expect to see larger fasted vs. fed differences in neural responsivity before (vs. after) surgery.

The aims of this study were to test the hypotheses that participants in this study would show: 1. larger pre- to post- operative neural changes in the fed vs. fasted state and; 2. larger fasted vs. fed differences in neural responsivity before (vs. after) surgery, as these results would align with postoperative changes and fasted vs. fed differences in postprandial gut peptides (Ochner et al., 2011b; Bose et al., 2010). Thus, although gut peptides were not assessed in this study, we anticipated gathering evidence consistent with the notion that postoperative changes in postprandial gut peptides may be driving postoperative changes in neural responsivity.

Methods

Participants

Five women candidates for RYGB surgery were recruited from the Center for Weight Loss Surgery at the St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York. Participants ranged in preoperative body mass index (BMI) from 39.1 – 48.1 (mean=44.0±3.8[SD]) kg/m2 and age from 21 – 54 (mean=36±13) years, were weight-stable (< 5% weight change in prior 3 mo), right-handed (in order to prevent handedness from affecting neural responsivity in this small sample), non-smoking, premenopausal, free of any major psychological or physical disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, diabetes, cardiovascular disease) and were not taking any medication that may have affected body weight. Exclusion criteria also included: a history of brain injury or brain surgery, metal implants, substance abuse (drugs and alcohol). These patients were not required to and did not lose weight prior to surgery. The same exclusion criteria were used in previous studies on this topic (Ochner et al., 2011a; 2012). The sample was 80% Hispanic and 20% African American. Institutional Review Board approval for this study was granted by Columbia University and St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital. All participants provided informed consent and met the criteria proposed by the NIH Consensus Panel in 1991 (NIH, 1991).

Design and procedure

A within-subjects design was used, with assessments at 1-month pre and 1-month post RYGB surgery. These time periods were chosen to remain consistent with previous work conducted in this area (Ochner et al., 2011b; 2012). All RYGB procedures were laparoscopic, performed in the same manner by the same surgeon. Postoperatively, the vertical pouch was approximately 5 cm long × 1 cm wide (~2 oz volume) with a 100 cm alimentary limb length and 30 cm biliopancreatic limb length. No adverse events or complications were reported.

Following an overnight (12 h) fast, participants reported to the fMRI Research Center at the Columbia University Medical Center between 11am and 1pm. Time of day was kept consistent across assessments for each participant. Forty-five minutes prior to scanning, participants ingested either a small (250 ml) nutritionally-complete liquid meal (Glytrol; Nestlé Nutrition, Vevey, Switzerland; 250 kcal) for fed state scans or 250 ml water for fasted state scans. The same volume (250 ml) of liquid meal and water was provided both pre and post surgery. Water was used to control for stomach volume and gastric distention. Participants rated hunger and fullness (visual analog scale, 0–100) just before scanning. Fed vs. fasted state scans were conducted in counterbalanced order on separate days within 72 h of each other. During fMRI scans, participants were presented with visual and auditory representations (cues) of high-calorie foods (e.g., pepperoni pizza, fudge sundae) and low-calorie foods (e.g., raw vegetables). All high-calorie cues had ≥ 3.5 kcal/g and all low-calorie cues had < 1 kcal/g (see Supplementary Table 1). All procedures were identical pre- and post- surgery.

Stimuli presentation paradigm

Visual (pictorial) cues were transmitted through eye goggles and auditory (spoken name) cues were transmitted through a headset. Stimuli were presented in runs of 10 consecutive four-second epochs (total block duration 40 s), with a 52-second pre run baseline epoch and a 40-second post run baseline epoch. A Latin-Square paradigm employed two similar, but not identical, nonconsecutive runs of each type of food cue (high-calorie, low-calorie) for each condition (visual and auditory). The auditory stimuli were recorded two-word names similar in content to the visual stimuli (e.g., “chocolate brownie”), repeated twice to fill the four-second epoch. Only areas activated in both stimuli presentation modalities were considered significant in image analyses, which helps eliminate sensory-specific activation (Friston et al., 2005).

fMRI Acquisition

A 1.5-Tesla twin-speed fMRI scanner (General Electric) with quadrature RF head coil and 65 cm bore diameter was used. Participants were positioned in the scanner with the head in a passive restraint. Three-plane localization was used to verify head position and motion was minimized with restraint pads around the head and a tape strapped across the forehead. Total time in the scanner was about 60 minutes. In each run, 36 axial scans of the whole brain were acquired, each scan consisting of 25 contiguous slices (4 mm thick), with a 19 × 19 cm field of view, an acquisition matrix size of 128 × 128 and 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm in plane resolution. The first three scans of each run (12 s) were discarded to attain magnetic equilibration. The axial slices were parallel to the AC/PC line. T2*-weighted images with a gradient echo pulse sequence (echo time = 60 ms, repetition time = 4 s, flip angle = 60°) were acquired with matched anatomic high resolution T1*-weighted scans.

fMRI Analyses

Whole brain functional data was analyzed with SPM5 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK). Prior to statistical analyses, the realigned T2*-weighted volumes were slice-time corrected, spatially transformed to a standardized brain (Montreal Neurologic Institute) and smoothed with an 8 mm full-width half-maximum Gaussian kernel. First level regressors were created by convolving the onset of each trial (audio and visual, high-calorie and low-calorie) with the canonical HRF with durat ion of 40 seconds for both pre- and post- surgery scan sessions. Both sessions were included in the 1st level model for each participant. Average beta estimates of each condition (12 total per participant) were passed to four second level models (pre, post, fasted, fed) from which all subsequent contrasts of interest were generated. Pre- to post- operative changes in BMI and pre-scan fullness ratings were included as nuisance regressors to control for postoperative weight loss and increases in postprandial fullness. t-values for neural responses to visual and auditory stimuli significant at p < 0.005 uncorrected were averaged to obtain areas activated across both modalities for pre-post analyses and entered concurrently in SPM analyses. Statistical maps for neural activation are shown at p < 0.005 uncorrected for display purposes. Significance was determined using a threshold of p < 0.005 uncorrected tested against the global null hypothesis, combined with a cluster-extent threshold of 145 contiguous voxels, resulting in a threshold of p < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons. The cluster threshold was determined by 1000 Monte Carlo simulations of whole-brain fMRI data with respective data parameters of the present study using the AlphaSim program as implemented in AFNI (version 2011, National Institutes of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Cox, 1996, 2011). Non-fMRI data were analyzed using SPSS versus18 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA), with two-tailed tests, α = 0.05. fMRI acquisition and analyses have also been previously described (Ochner et al., 2011a; 2012).

Results

Body weight, hunger and fullness

Pre- and post- operative body weights are reported in Supplementary Table 2. Hunger and fullness ratings pre and post surgery in fasted and fed states are shown in Supplementary Table 3. From pre to post RYGB, the only significant change was a decrease in hunger in the fasted state (p = 0.03).

Fasted state pre- to post- operative change in neural responsivity

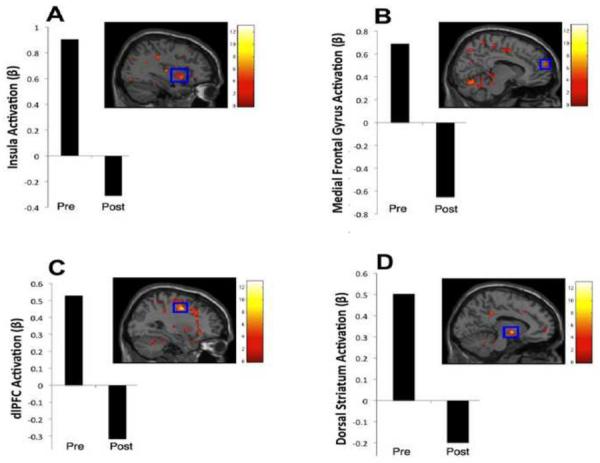

Significant pre- to post- operative reductions in neural responsivity to high- vs. low-calorie food cues were noted in the gustatory cortex (insula; Fig. 1A), reward-related aspects of the prefrontal cortex (medial frontal gyrus [mesolimbic pathway]; Fig. 1B), inhibitory areas (middle and superior frontal gyri [dlPFC]; Fig 1C), the motor cortex (precentral gyrus) and sensory areas (middle and superior temporal gyri). A large but nonsignificant cluster (k = 119) was also noted in the dorsal striatum (lentiform nucleus [reward]; Fig. 1D). No significant postoperative increases in neural responsivity were noted. See Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Areas in which responsivity to (high- vs. low- calorie) food cues decreased from pre to post RYGB when Ss were assessed in the fasted state. Preoperative Fasted – Fed, High- – Low- Calorie Food Cue Contrast. Clockwise from upper left: A) insula;* B) medial frontal gyrus; C) dorsal striatum; D) dlPFC. The color bars represent t values. For display purposes, activation maps are shown without a cluster extent threshold. All clusters and coordinates (x,y,z) are presented in Table 1. *significant at p < 0.05 corrected.

Table 1.

Areas showing postoperative reductions in the fasted state in response to high-calorie relative to low-calorie food cues.

| Coordinates (x,y,z) | Area(s) | Hemisphere | k | Maximum t-value | Effect Size (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −44, −50, 10 | superior temporal gyrus*,1 | L | 1177 | 8.81 | 8.81 |

| middle temporal gyrus*,1 | |||||

| culmen*,1 | |||||

| 30, −4, 44 | middle frontal gyrus* | R | 698 | 9.51 | 9.51 |

| precentral gyrus*,2 | |||||

| −26, −10, 66 | middle frontal gyrus*,2 | L | 418 | 6.89 | 6.89 |

| superior frontal gyrus*,2 | |||||

| −40, −76, 14 | middle temporal gyrus*,3 | L | 370 | 6.34 | 6.34 |

| precuneus*,3 | |||||

| 8, −68, −16 | declive*,4 | R | 346 | 6.26 | 6.26 |

| culmen*,4 | |||||

| 36, 8, −8 | insula*,5 | R | 170 | 5.97 | 5.97 |

| claustrum*,5 | |||||

| 10, 60, 20 | superior frontal gyrus*,6 | R | 150 | 7.35 | 7.35 |

| medial frontal gyrus*,6 | |||||

| −10, −4, −4 | lentiform nucleus | L | 119 | 8.34 | 8.34 |

Within these clusters, those larger than 145 voxels are deemed significant at p < 0.05 corrected.

k = Number of voxels within each cluster.

Significant at p < 0.05 corrected.

Part of the same cluster.

Fed state pre- to post- operative change in neural responsivity

No significant postoperative changes in neural responsivity were noted, although nonsignificant clusters were seen in areas previously reported (Ochner et al., 2011a). See Supplementary Table 4.

Preoperative fasted vs. fed state differences in neural responsivity

Preoperatively, neural responsivity was greater in the fasted vs. fed state in contextual (precuneus) and sensory (superior parietal lobule) areas. Large but nonsignificant clusters (k = 123–129) were also seen in reward-related (medial frontal gyrus) and inhibitory (middle & superior frontal gyrus; dlPFC) areas (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 5).

Postoperative fasted vs. fed state differences in neural responsivity

Postoperatively, no significant differences in neural responsivity were noted in the fasted vs. fed state. Note: no areas showed greater responsivity in the fed vs. fasted state pre- or post-surgery.

Discussion

Pre- to post- operative changes in neural responsivity

In the fed state, postoperative reductions in mesolimbic activation reported previously (e.g., dorsal striatum; Ochner et al., 2011a) failed to reach significance with the application of a cluster threshold, likely reflecting limited power afforded by the small sample. Interestingly, in the fasted state however, relatively robust postoperative reductions in neural responsivity were observed in areas within the mesolimbic pathway and gustatory cortex, suggesting that postoperative changes in neural responsivity in the fasted state were more robust than postoperative changes in the fed state noted here and in the prior sample. Thus, results were not only unexpected, but opposite to that which was hypothesized, indicating that postoperative reductions in mesolimbic responsivity were larger in the fasted relative to the fed state. This unanticipated finding may be partially explained by differential effects of hunger and fullness in the fasted vs. fed state (Supplementary Table 3). There was a large postoperative decrease in hunger ratings in the fasted but not fed state. However, there were no significant postoperative changes in fullness ratings in either state (fasted or fed). Thus, the larger postoperative decreases in hunger in the fasted vs. fed state may have driven the larger postoperative changes in mesolimbic responsivity seen in the fasted vs. fed state. Regardless of cause, however, this finding appears inconsistent with the theory that postoperative changes in postprandial gut peptides are the primary driver of postoperative changes in neural responsivity.

Fasted vs. fed differences in neural responsivity

Preoperatively, fasted vs. fed differences in neural responsivity to food cues in this sample were relatively consistent with prior studies, reporting more reward-related responsivity to palatable food cues in the fasted vs. fed state (Goldstone et al., 2009; Führer et al., 2008). This may be at least partially explained by evidence of hypothalamic up-regulation of mesolimbic signaling during periods of caloric deficit (Berthoud & Morrison, 2008). Thus it was anticipated that there would be greater mesolimbic responsivity to food cues in the fasted vs. fed state both pre- and post- surgery. Further, it was anticipated that the fasted vs. fed difference in mesolimbic responsivity would be larger post- vs. pre- surgery, based on the supposition that larger post- vs. pre- surgery difference in satiety hormone levels were driving postoperative changes in neural responsivity (Ochner et al., 2010).

Data from this study again failed to support the relevant a priori hypothesis, with results showing a trend opposite in direction to that hypothesized. Although preoperative fasted vs. fed state differences in mesolimbic areas failed to reach significance with the applied cluster threshold, no areas even approached significance for postoperative fasted vs. fed differences (largest cluster = lingual gyrus, k = 28). Thus, contrary to a priori hypotheses, data from this study suggest larger differences in neural responsivity between the fasted and fed states pre relative to post RYGB. Although not as robust as pre to post RYGB changes in postprandial gut peptide levels, there is some evidence suggesting short-term (i.e., to 1 mo post) decreases in fasting ghrelin, and increases in fasting PYY3–36, following RYGB (Korner et al., 2009; Karamanakos et al., 2008). These changes could have served to decrease hunger and increase the fullness effect of the water control in the fasting condition, limiting postoperative fasted vs. fed differences. A postoperative decrease in ghrelin could potentially explain the unanticipated decrease in hunger in fasted condition (Supplementary Table 3). Further, ghrelin has been shown to play an important role in neural reward processing, suggesting that potential relations with fasting peptides should be explored in subsequent research (Skibicka and Dickson, 2011; Skibicka et al., 2011). Again, however, findings appear inconsistent with the hypothesis that postoperative changes in postprandial gut peptides are the primary driver of postoperative changes in neural responsivity.

Future Directions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to address the potential relation between changes in gut peptides and neural responsivity following obesity surgery. The ultimate goal of this line of research is to replicate the lasting weight loss produced by RYGB through nonsurgical methods, so called “knifeless RYGB” (Shin & Berthoud, 2011). Under the premise that the brain controls all non-reflexive behavior (Grobstein, 1994), and with new non-invasive treatments being developed to directly manipulate neural responsivity (McCaig et al., 2011), an attempt to replicate the changes in neural responsivity seen with RYGB may prove fruitful in increasing the effectiveness and sustainability of nonsurgical weight loss interventions for obese individuals (Shin & Berthoud, 2011; Stoeckel et al., 2008). In line with this rationale, recent research has demonstrated associations between changes in neural responsivity and changes in body weight (Stice et al., 2010). Identifying the primary driver of the changes in neural responsivity associated with the only sustainable weight loss intervention (bariatric surgery) may help achieve beneficial alterations in neural responsivity to food cues, eating behavior and body weight through noninvasive means. Given the preliminary nature of the current study, these data cannot be taken as evidence refuting the hypothesis that post RYGB changes in gut peptides are the primary driver of postoperative changes in neural responsivity; however, this study does suggest the possibility that this supposition may not be correct and requires further investigation.

Limitations

Gut peptides and satiety were not assessed in this study. Thus, statements regarding the association between gut peptides and neural responsivity are speculative. Future research should assess gut peptides concurrently with neural responsivity, as well as satiety, in larger samples to ensure adequate power. All participants were female, limiting generalizability. Sample size was limited due to difficulty recruiting patients willing to commit to two additional appointments on separate days (one fasted, one fed) both pre and post surgery, even with data collection spanning over more than a year. It is important to note that the longitudinal within-subjects design did provide sufficient power to detect effects in the fasted state with the application of a k-correction threshold. Further, the limited sample size helped make the relative changes and differences in neural responsivity readily apparent, as the relative changes and differences hypothesized to be larger not only failed to be larger but failed to even reach significance. Finally, in interpreting results, it is important to bear in mind that inferences cannot be made based solely upon pilot project data such as those presented in this paper. Given the limited sample, results are also not generalizable to males, other races, ages or BMIs.

Conclusion

Based on studies demonstrating significant post RYGB changes in neural responsivity to food cues (Ochner et al., 2011a; 2012) and postprandial gut peptides (Ochner et al., 2011b; Bose et al., 2010), and the potential for gut peptides to affect neural responsivity (Berthoud & Morrison, 2008; Moran and Dailey, 2011), we speculated that postoperative changes in postprandial gut peptides may be the primary driver of postoperative changes in neural responsivity. Thus, we predicted that postoperative changes in neural responsivity would be greater in the fed relative to the fasted state (mirroring changes in gut peptides) and that the difference between neural responsivity in the fasted vs. fed state would be greater post relative to pre RYGB (also mirroring gut peptides). Contrary to a priori predictions, postoperative reductions in neural responsivity were greater in the fasted relative to the fed state, and the difference between neural responsivity in the fasted vs. fed state was greater pre relative to post RYGB. These findings appear inconsistent with the notion that postoperative changes in postprandial gut peptides are the primary driver of the previously reported postoperative changes in neural responsivity in the examined brain areas involved in rewarding food cues. Although these inferential conclusions represent the thinking of these authors, it is important to note that alternate conclusions may be drawn from this data. Regardless, caution must be taken in interpreting small sample results and prospective replication is needed.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

We test fasted vs. fed state differences in neural responsivity to food cues

We test post bariatric surgery change in neural responses in fasted and fed states

Postoperative decreases in gustatory/reward responsivity in the fasted state

Surprising results inconsistent with popular notion

Acknowledgements

We thank Stephen Dashnaw and Andrew Kogan for conducting the fMRI scans, as well as Danielle Binler for her assistance with image analyses.

Role of the Funding Source This research was funded by NIH grants KL2RR024157, P30DK26687 and R56DK080153. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors Dr. Ochner conceived of the study, provided funding support and wrote the manuscript. Dr. Laferrère assisted in interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. Ms. Afifi conducted image analyses and assisted in manuscript preparation. Dr. Atalayer assisted in manuscript preparation. Mr. Pantazatos assisted in image analyses and interpretation of results. Dr. Geliebter assisted in study conception, provided study support and assisted in manuscript editing. Dr. Teixeira was the study surgeon and assisted in manuscript editing. Dr. Hirsch oversaw fMRI scanning and manuscript preparation.

dlPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

PYY3-36 = peptide YY3-36

GLP-1 = glucagon-like peptide-1

BMI = body mass index

References

- Ashrafian H, le Roux CW. Metabolic surgery and gut hormones - a review of bariatric entero-humoral modulation. Physiol Behav. 2009;97:620–631. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud H-R, Morrison C. The brain, appetite, and obesity. Ann Rev Psychol. 2008;59:55–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose M, Machineni S, Oliván B, Teixeira J, McGinty JJ, Bawa B, Koshy N, Colarusso A, Laferrère B. Superior appetite hormone profile after equivalent weight loss by gastric bypass compared to gastric banding. Obesity. 2010;18:1085–1091. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and biomedical research. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: What a long strange trip it's been. Neuroimage. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.056. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DE, Overduin J, Foster-Schubert KE. Gastric bypass for obesity: mechanisms of weight loss and diabetes resolution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2608–2615. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Penny WD, Glaser DE. Conjunction revisited. Neuroimage. 2005;25:661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Führer D, Zysset S, Stumvoll M. Brain activity in hunger and satiety: An exploratory visually stimulated fmri study. Obesity. 2008;16:945–950. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone AP, Prechtl de Hernandez CG, Beaver JD, Muhammed K, Croese C, Bell G, Durighel G, Hughes E, Waldman D, Frost G, Bell JD. Fasting biases brain reward systems towards high-calorie foods. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1625–1635. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobstein P. Variability in brain function and behavior. In: Ramachandran VS, editor. The Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 447–458. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, Alexandrides TK. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-yy levels after roux-en-y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: A prospective, double blind study. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401–407. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318156f012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner J, Inabnet W, Febres G, Conwell IM, McMahon DJ, Salas R, Taveras C, Schrope B, Bessler M. Prospective study of gut hormone and metabolic changes after adjustable gastric banding and roux-en-y gastric bypass. Int J Obes. 2009;33:786–795. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaig RG, Dixon M, Keramatian K, Liu I, Christoff K. Improved modulation of rostrolateral prefrontal cortex using real-time fMRI training and meta-cognitive awareness. Neuroimage. 2011;55:1298–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran TH, Dailey MJ. Intestinal feedback signaling and satiety. Physiol Behav. 2011;105:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consensus development conference panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:956–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochner CN, Gibson C, Carnell S, Dambkowski C, Geliebter A. The neurohormonal regulation of energy intake in relation to bariatric surgery for obesity. Physiol Beh. 2010;100:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochner CN, Gibson C, Shanik M, Goel V, Geliebter A. Changes in neurohormonal gut peptides following bariatric surgery. Int J Obes. 2011b;35:153–166. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochner CN, Kwok Y, Conceicao E, Pantazatos SP, Puma LM, Carnell S, Teixeira J, Hirsch J, Geliebter A. Selective reduction in neural responses to high calorie foods following gastric bypass surgery. Ann Surg. 2011a;253:502–507. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318203a289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochner CN, Stice E, Hutchins E, Afifi L, Geliebter A, Hirsch J, Teixeira J. Relation between changes in neural responsivity and reductions in desire to eat high-calorie foods following gastric bypass surgery. Neurosci. 2012;209:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin AC, Berthoud HR. Food reward function as affected by obesity and bariatric surgery. Int J Obes. 2011;35:S40–S44. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibicka KP, Dickson SL. Ghrelin and food reward: the story of potential underlying substrates. Peptides. 2011;32:2265–73. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibicka KP, Hansson C, Alvarez-Crespo M, Friberg PA, Dickson SL. Ghrelin directly targets the ventral tegmental area to increase food motivation. Neurosci. 2011;180:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Yokum S, Blum K, Bohon C. Weight gain is associated with reduced striatal response to palatable food. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13105–13109. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2105-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckel LE, Weller RE, Cook EW, Twieg DB, Knowlton RC, Cox JE. Widespread reward-system activation in obese women in response to pictures of high-calorie foods. Neuroimage. 2008;41:636–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.