Abstract

Background

In recent years, Nocardia farcinica has been reported to be an increasingly frequent cause of localized and disseminated infections in the immunocompromised patient. However, recent literature is limited. We report a case of left thigh phlegmon caused by N. farcinica that occurred in a patient with Leprosy undergoing treatment with prednisone for leprosy reaction.

Case presentation

We describe the case of left thigh phlegmon caused by Nocardia farcinica in a 54-year-old Italian man affected by multi-bacillary leprosy. The patient had worked in South America for 11 years. Seven months after his return to Italy, he was diagnosed with Leprosy and started multi-drug antibiotic therapy plus thalidomide and steroids. Then, during therapy with rifampicin monthly, minocycline 100 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, and prednisone (the latter to treat type 2 leprosy reaction), the patient complained of high fever associated with erythema, swelling, and pain in the left thigh. Therefore, he was admitted to our hospital with the clinical suspicion of cellulitis. Ultrasound examination and Magnetic Resonance Imaging showed left thigh phlegmon. He was treated with drainage and antibiotic therapy (meropenem and vancomycin replaced by daptomycin). The responsible organism, Nocardia farcinica, was identified by 16S rRNA sequencing in the purulent fluid taken out by aspiration. The patient continued treatment with intravenous trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and imipenem followed by oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and moxifloxacin. A whole-body computed tomography did not reveal dissemination to other organs like the lung or brain.

The patient was discharged after complete remission. Oral therapy with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, moxifloxacin, rifampicin monthly, clofazimine and thalidomide was prescribed to be taken at home. One month after discharge from the hospital the patient is in good clinical condition with complete resolution of the phlegmon.

Conclusion

N. farcinica is a rare infectious agent that mainly affects immunocompromised patients. Presentation of phlegmon only without disseminated infection is unusual, even in these kinds of patients. In any case, a higher index of suspicion is needed, as diagnosis can easily be missed due to the absence of characteristic symptoms and the several difficulties usually encountered in identifying the pathogen.

Keywords: Nocardia, Hansen’s disease, Phlegmon

Background

Nocardiosis is a localized or disseminated uncommon infection caused by an aerobic Actinomycetes of the genus Nocardia[1]. Approximately 50 species of Nocardia have been characterized [2], with at least 16 species being recognized as human pathogens [3]. These organisms are opportunistic pathogens affecting immunocompromised hosts, including those with long-term corticosteroid exposure, malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and a history of transplantation [4]. Earlier reports estimated the occurrence of 500–1,000 new cases each year in the USA, and 150–200 and 90–130 in France and Italy, respectively [5-7]. N. asteroides, N. farcinica and N. nova caused approximately 85% of the total cases [8-10]. An increase in the diagnosis of N. farcinica infection is due to the growing population of immunocompromised hosts and improved methods for detecting and identifying the Nocardia species. This microorganism can cause localized or disseminated infections that can be life-threatening without prompt diagnosis and proper treatment; furthermore, it is characteristically resistant to multiple anti-microbial agents, including third-generation cephalosporin [1,11].

We report the case of left thigh phlegmon caused by N. farcinica that occurred in a patient affected by Leprosy undergoing treatment with prednisone for leprosy reaction.

Case presentation

A 54 year old Italian man was admitted to the “Lazzaro Spallanzani” National Institute for Infectious Diseases of Rome because of fever, cutaneous lesions and sensory loss of peripheral nerves. He had worked in Venezuela for eleven years. A histological examination of a skin biopsy showed the presence of Mycobacterium leprae and the patient was diagnosed as borderline lepromatous (BL) leprosy complicated by erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) reaction. His bacteriological index (total bacterial load) was 4.17+ (normal range 0-6+) and the morphological index (percentage of bacilli uniformly stained) 0.5%. He was treated with rifampicin monthly and minocycline and moxifloxacin daily. The ENL was recurrent and treated with oral prednisone (75 mg) and thalidomide. Sixteen months after starting therapy for Leprosy (and after about a year of steroid therapy), the patient started to complain of high fever (39°C) associated with erythema, swelling and pain of left thigh, and he was admitted to our hospital for the second time with suspicion of cellulitis. He referred that the symptoms had started about 7 days before admission, but he denied a history of local trauma or recreational drug abuse. Diabetes mellitus had been diagnosed two months before.

On physical examination, his vital signs were as follows: temperature 39°C, blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, pulse rate 95 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 15 breaths per minute. Laboratory examinations revealed: white blood cells (WBC) 14,500/μL (4,3-10,8) (87% neutrophils, 4.1% lymphocytes), haemoglobin 11 g/dL (12–18), platelets 234,000/μL (80,000 – 400,000), C-reactive protein (CRP) 32 mg/dL (0–0.16), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 82 mm/h (0–15). Chest X-ray was normal. Ultrasound examination and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the lower extremities revealed left thigh phlegmon (Figure 1). Ultrasound guided incision and drainage were performed at the bedside with leaking, copious amounts of pus. Samples were sent to the laboratory for Gram and acid -fast bacilli staining, cultures, and PCR amplification of bacterial DNA. Furthermore, more sets of blood cultures were performed.

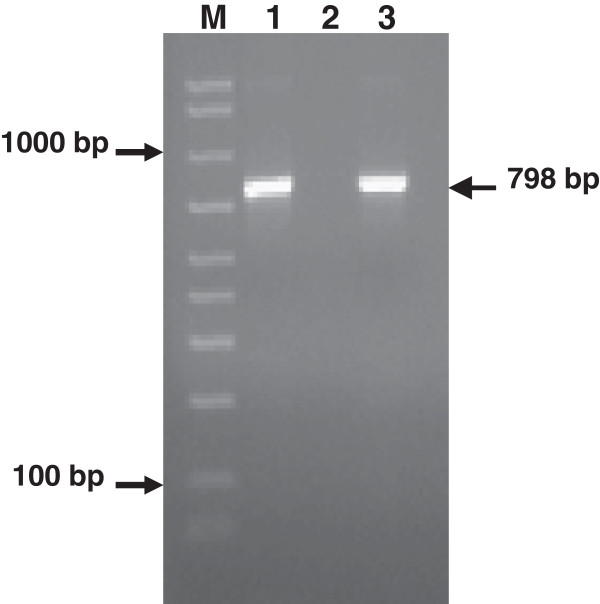

Figure 1.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of left thigh at admission. a. T1 after contrast coronal image showing hyperintense necrotic lesion of the left thight; b. T2 FLAIR weighted sagittal image of the same lesion that appear hypointense.

Intravenous vancomycin and meropenem were started: 500 mg every six hours, and 1 g every 8 hours, respectively, and moxifloxacin and minocycline were stopped. Incision was repeated on hospital day 3 and vancomycin was replaced by daptomycin for the persistence of high fever; prednisone was reduced to 50 mg. After 96 hours of incubation, blood cultures and aerobic and anaerobic cultures of the sample were negative. On day 6, the patient had type 2 leprosy reaction and prednisone was again increased to 75 mg. Seven days after initiating daptomycin, an ultrasound examination showed the first decrease of both phlegmon volume and peripheral oedema.

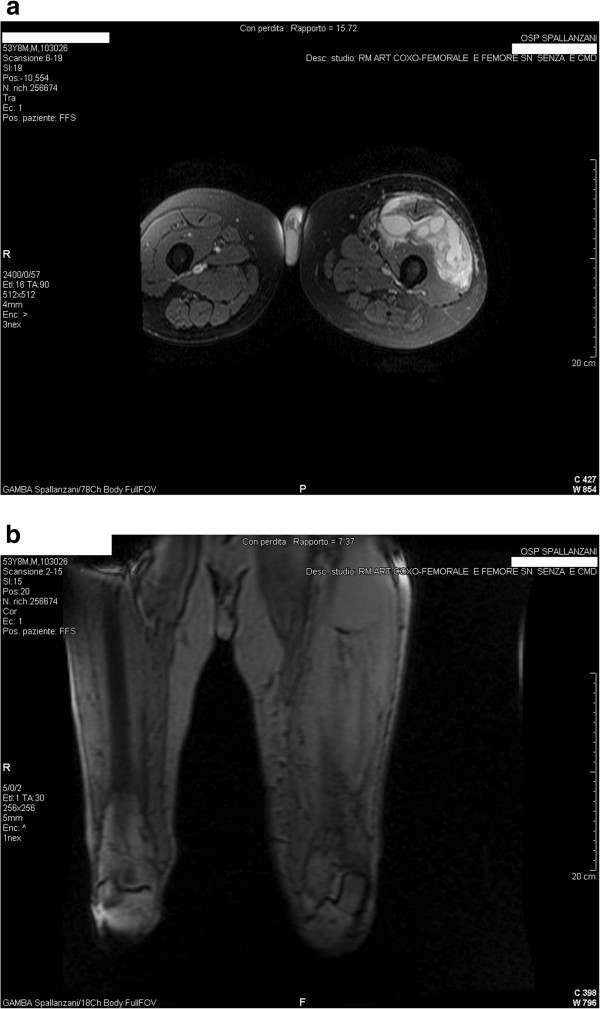

On hospital day 15, the pathogen was identified as N. farcinica by 16S rRNA gene sequencing in the purulent fluid, whereas the cultures were negative. Amplified PCR products (Figure 2) were purified and directly sequenced. Related DNA sequences were searched in GenBank by using the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) server. The most closely related sequences belonged to Nocardia farcinica species. The further identity of the pathogen was also confirmed by sequencing a region of 16S rRNA gene of Nocardia with a PCR that used genus-specific primers [12]. Sequence data of the amplified PCR products showed great identity (99%) to the species Nocardia farcinica

Figure 2.

Two percent agarose gel electrophoresis showing the product of amplification of the 798-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene. DNA sequencing of such a fragment further allowed the identification of Nocardia farcinica. Lane 1 = PCR product obtained from a phlegmon sample of our patient; lane 2 = negative control (water); lane 3 = positive control (Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619); M = DNA size reference marker (50-2000-bp Amplisize, Biorad).

The patient was shifted to a therapy based on intravenous trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and imipenem for 1 month. A whole-body computed tomography (CT-scan) revealed no dissemination to other organs like the lung or brain. On hospital day 22, prednisone was stopped and the leprosy reaction was treated with clofazimine and thalidomide. After a month of therapy, MRI revealed a decreased amount of phlegmon without osteomyelitis of the left femur (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging performed after a month of antibiotic therapy shows complete resolution of the phlegmon.

The patient was discharged after complete remission at day 51 with a prescription of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, moxifloxacin, rifampicin monthly, clofazimine and thalidomide.

One month after discharge from the hospital the patient is in good clinical condition.

Conclusion

N.farcinica is a Gram–positive, branching, filamentous bacillus causing many localized and disseminated infectious in humans, including pulmonary and wound infections, brain abscesses, and bacteraemia. Immunocompromised hosts and patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapies are more commonly affected by this bacterium [2].

Anton Y. Peleg et al. described the risk factors of N. farcinica infection in organ transplant recipients. In this case series, patients with Nocardia infection had significantly higher prednisone dosages (p 0.007), lower lymphocyte counts (p 0.003), and higher neutrophil counts (p 0.006) at the time of infection, compared with control subjects [13]. In our case, the patient had undergone therapy with prednisone in the preceding 12 months because of leprosy reaction. At admission he had WBC 14,500/μL with neutrophils 87% (11800/mmc), lymphocytes 4.1% (500/mmc), CD4 cells 34.6% (463/mmc), CD8 cells 24.8% (322/mmc).

The relative frequency of infections caused by the different Nocardia species are difficult to determine retrospectively and may vary geographically. N. farcinica has been reported to constitute 13,8% and 19% of Nocardia isolates in Italy from 1982 to 1992 [14] and from 1993 to 1997 [7], respectively. It is not possible to estimate the actual number of Italian cases due to the potential bias of referrals to public health authorities and also because Nocardia strains are not collected at the National Reference Centre.

The clinical manifestations of N. farcinica are different. The lung is the most common site of infection (43%). Torres et al. observed infections of cutaneous and sub-cutaneous tissues in 10% of cases. In the case of disseminated infections, it was possible to detect a metastatic focus or, more frequently, a primary lesion after traumatic injury. In other cases, the patients had sub-clinical or transient primary pulmonary infection followed by dissemination to the brain, skin, bones, and kidney [15]. In our case, as in the 7/26 cases described in an Italian report about human Nocardiosis between 1993 and 1997 [7], it was not possible to observe previous pulmonary involvement.

Concerning the epidemiology, Nocardiae are ubiquitous in the environment and can be found worldwide in fresh and salt water, in a variety of soil types, dust, decaying vegetation, and decaying faecal deposits from animals [2]. Bittar et al. described a Nocardia infection in a man who was an active gardener [16]. Our patient had gardening as a hobby, which led us to speculate that he could have acquired the infection in this way.

Unfortunately, we did not identify the organism with the cultures and could not perform susceptibility testing. However, previous studies have identified multi-drug-resistance patterns in isolates of N. farcinica, characterized by resistance to most beta-lactam antibiotics [17] and susceptibility mainly to amikacin, imipenem, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and fluoroquinolones [2]. Hansen G. et al. reported that fluoroquinolones had variable activity against clinical strains of Nocardia, and the newer fluoroquinolones such as moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, and gemifloxacin, had increased in vitro activity compared to ciprofloxacin [17].

Laboratory identification and speciation for Nocardia are challenging, and the methodology continues to evolve. Before 2000, Nocardia isolates were identified primarily through phenotypic methods. In 2000, the identification of Nocardia was enhanced through the use of 16SrRna gene sequencing in research centres [18-20]. In the reported case, it is interesting to underline that our patient presented clinical and radiological improvement after the initiation of therapy with daptomycin. Since no cases of N. farcinica treated with daptomycin have been described in literature (there are only sensitivity studies in vitro) [21], we started empirical antibiotic combination therapy with imipenem plus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Information on the duration of treatment is inadequately documented in most reports, varying from 3 to 12 months with a median of 4 months. Primary cutaneous Nocardiosis may be treated with therapy for 2 to 4 months, but only after bone involvement has been excluded [4,6].

In summary, Nocardiosis remains a severe and sometimes potentially life-threatening complication in the immunocompromised host. It is relevant to consider this microorganism in the differential diagnosis of infections, even in cases with unusual presentations such as this one. Because of the aggressiveness, tendency to disseminate, and resistance of the organism to antibiotics, delayed diagnosis can have serious consequences.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

WBC: White blood cells; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; CT: Computed tomography

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AC and PDN took care of the patient and wrote the case report; MGP did the laboratory work; MLG and PG took care of the patient; EG, CT, RT took part in the drafting; SN, EN and AA contributed to literature search and reviewed the final manuscript; all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Pasquale De Nardo, Email: dr.pasqualedenardo@gmail.com.

Maria Letizia Giancola, Email: mletizia.giancola@inmit.it.

Salvatore Noto, Email: salvatore.noto@hsanmartino.it.

Elisa Gentilotti, Email: e.gentilotti@libero.it.

Piero Ghirga, Email: piero.ghirga@inmi.it.

Chiara Tommasi, Email: chiara.tommasi@inmi.it.

Rita Bellagamba, Email: rita.bellagamba@inmi.it.

Maria Grazia Paglia, Email: pagliamicromol@inmi.it.

Emanuele Nicastri, Email: emanuele.nicastri@inmi.it.

Andrea Antinori, Email: andrea.antinori@inmi.it.

Angela Corpolongo, Email: angela.corpolongo@inmi.it.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to offer their special thanks to Andrea Baker for english revision.

References

- Lerner PI. In: Nocardia species. Mandell/Douglas/Bennetts, editor. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases; pp. 2273–2280. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallace RJ Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp, based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259–282. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.259-282.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saubolle MA, Sussland D. Nocardiosis: review of clinical and laboratory experience. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4497–4501. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4497-4501.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner PI. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891–903. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaman BL, Burnside J, Edwards B, Causey W. Nocardial infections in the United States, 1972–1974. J Infect Dis. 1976;134:286–289. doi: 10.1093/infdis/134.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiron P, Provost F, Chevrier G, Dupont B. Review of nocardial infections in France, 1987–1990. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:709–714. doi: 10.1007/BF01989975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina C, Boiron P, Ferrari I, Provost F, Goglio A. Report of human nocardiosis in Italy between 1993 and 1997. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:1019–1022. doi: 10.1023/A:1020010826300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamura M, Ohta M. Nocardia farcinica as a pathogen of lung infection. Microbiol Immunol. 1980;24:237–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1980.tb00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl G, Schaal KP, Kochsieck K. Nocardial endocarditis of an aortic valve prosthesis. Br Heart J. 1987;57:384–386. doi: 10.1136/hrt.57.4.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamura M, Shimoide H, Kaneda K, Sakai R, Seino A. A case of lung infection caused by an unusual strain of Nocardia farcinica. Microbiol Immunol. 1988;32:541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1988.tb01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RJ, Tsukamura M, Brown BA, Brown J, Steingrube VA, Zhang Y, Nash D. Cefotaxime resistant Nocardia asteroides strains are isolates of the controversial species Nocardia farcinica. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2726–2732. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2726-2732.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent FJ, Provost F, Boiron P. Rapid identification of clinically relevant Nocardia species to genus level by 16S rRNA gene PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:99–102. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.1.99-102.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg AY, Husain S, Qureshi ZA, Silveira FP, Sarumi M, Shutt KA, Kwak EJ, Paterson DL. Risk Factors, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcome of Nocardia Infection in Organ Transplant Recipients: A Matched Case–control Study. Clin Inf Dis. 2007;44:307–1314. doi: 10.1086/514340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina C, Boiron P, Goglio A, Provost F. Human nocardiosis in northern Italy from 1982 to 1992. Northern Collaborative Group on Nocardiosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1999;27:23–27. doi: 10.3109/00365549509018968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres OH, Domingo P, Pericas R, Boiron P, Montiel JA, Vazquez G. Infection Caused by Nocardia farcinica: Case report and Review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s100960050460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittar F, Stremler N, Audié JP, Dubus JC, Sarles J, Raoult D, Rolain JM. Nocardia farcinica lung infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:84. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen G, Swanzy S, Gupta R, Cookson B, Limaye AP. In vitro activity of fluoroquinolones against clinical iolates of Nocardia identified by partial 16S rRNA sequencing. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud JL, Conville PS, Croft A, Harmsen D, Witebsky FG, Carroll KC. Evaluation of partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing for identification for Nocardia species by using the MicroSeq 500 system with an expanded database. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:578–584. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.578-584.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JB, Leonard DGB, Pan X, Musser JM, Berman RE, Nachamkin I. Sequence based identification of Mycobacterium species using the MicroSeq 500 16SrDNA bacterial identification system. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:246–251. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.246-251.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Andress S, Kroppenstedt RM, Harmsen D, Mauch H. Phylogeny of the genus Nocardia based on reassessed 16SrRNA gene sequences reveals underspeciation and division of strains classified as Nocardia asteroids into three established species and two unnamed taxons. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:851–856. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.851-856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Liao CH, Teng LJ, Hsueh PR. Daptomycin Susceptibility of Unusual Gram-Positive Bacteria: Comparison of Results Obtained by the Etest and the Broth Microdilution Method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1570–1572. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01352-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]