Abstract

Background

Miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) are expected to play important roles in evolution of genes and genome in plants, especially in the highly duplicated plant genomes. Various MITE families and their roles in plants have been characterized. However, there have been fewer studies of MITE families and their potential roles in evolution of the recently triplicated Brassica genome.

Results

We identified a new MITE family, BRAMI-1, belonging to the Stowaway super-family in the Brassica genome. In silico mapping revealed that 697 members are dispersed throughout the euchromatic regions of the B. rapa pseudo-chromosomes. Among them, 548 members (78.6%) are located in gene-rich regions, less than 3 kb from genes. In addition, we identified 516 and 15 members in the 470 Mb and 15 Mb genomic shotgun sequences currently available for B. oleracea and B. napus, respectively. The resulting estimated copy numbers for the entire genomes were 1440, 1464 and 2490 in B. rapa, B. oleracea and B. napus, respectively. Concurrently, only 70 members of the related Arabidopsis ATTIRTA-1 MITE family were identified in the Arabidopsis genome. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that BRAMI-1 elements proliferated in the Brassica genus after divergence from the Arabidopsis lineage. MITE insertion polymorphism (MIP) was inspected for 50 BRAMI-1 members, revealing high levels of insertion polymorphism between and within species of Brassica that clarify BRAMI-1 activation periods up to the present. Comparative analysis of the 71 genes harbouring the BRAMI-1 elements with their non-insertion paralogs (NIPs) showed that the BRAMI-1 insertions mainly reside in non-coding sequences and that the expression levels of genes with the elements differ from those of their NIPs.

Conclusion

A Stowaway family MITE, named as BRAMI-1, was gradually amplified and remained present in over than 1400 copies in each of three Brassica species. Overall, 78% of the members were identified in gene-rich regions, and it is assumed that they may contribute to the evolution of duplicated genes in the highly duplicated Brassica genome. The resulting MIPs can serve as a good source of DNA markers for Brassica crops because the insertions are highly dispersed in the gene-rich euchromatin region and are polymorphic between or within species.

Keywords: Miniature Inverted-repeat Transposable Element (MITE), MITE insertion polymorphism (MIP), Brassica species, Evolution, BRAMI-1

Background

The large-scale sequencing of eukaryotic genomes has revealed that transposable elements (TEs) are present ubiquitously and occupy large fractions of genomes: 5% in yeast, 35% in rice, 45% in human, and up to 85% in maize [1-9]. TEs are classified into two classes based on their transposition mechanism. Class I mobile genetic elements, or retrotransposons, are replicated through RNA intermediates by a copy-and-paste mechanism, whereas Class II mobile genetic elements, or DNA transposons, move directly from DNA via a cut-and-paste mechanism [1,2,10].

Miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) are Class II DNA transposons that are non-autonomous, with defective or absent of coding genes. MITEs were identified in the maize genome [11] and later found in Arabidopsis, rice, grape, mosquito, fish, bacteria and human as well as in several other genomes [1,12-15]. Due to their extremely high copy numbers, MITEs can account for a significant fraction of a eukaryotic genome (i.e. >8% of the rice genome) even though the size of element itself is small [16]. Individual MITEs are usually less than 600 bp and A/T rich, with terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) and 2–11 bp target site duplication (TSD) sequences [1,10]. MITEs, which are relatively stable in the genome, are often closely associated with genic regions and thus can affect gene expression patterns [16,17]. Some MITEs are involved in up-regulation of host genes by providing additional recognition sequences or polyA signals to host genes [14,18,19]. MITE insertion into regulatory regions may cause disruption or promotion of gene expression [18]. Recent studies have found that MITEs are also a source of small interfering RNA (siRNA) evolution and may play an important role in gene regulation and epigenetic mechanisms [16,20-22]. MITE transposition into a new region of the genome causes insertion polymorphisms among accessions of same species that can be useful tools for development of various markers [23,24].

The Brassicaceae family includes 338 genera and 3700 species, which serve as sources of vegetable, fodder, condiments and oil, with wide range of morphologies, such as Chinese cabbage, mustard, cabbage, broccoli, oilseed rape, and other leafy vegetables. The model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana is a close relative of the Brassica species and belongs to the same family. As a model Brassica crop, the B. rapa genome sequence spanning 256 Mb euchromatin chromosome spaces was completed recently and released to the public [25].

Comparative analysis of Brassica species with A. thaliana has revealed up to two additional rounds of recent genome duplication: one triplication and one allopolyploidization that is the major factor responsible for the increased genome size of Brassica[25-27]. In addition, TEs also contribute to increase the genome size of the Brassica species and to genome evolution [28]. The completed genome sequence of B. rapa revealed that at least 39.5% of the genome contains TEs [25].

In this study, we identified a new MITE named Brassica rapaMITE (BRAMI)-1, which is present in more than 1400 copies in the genome of each of three Brassica species. We inspected its characteristics and distribution and inferred its potential involvement in the evolution of duplicated genes in the highly replicated Brassica genome. We also discovered high amounts of insertion polymorphism inter- and intra-species, which can serve a good source of genetic markers in the Brassica species.

Results

Characterization of BRAMI-1 in Brassica

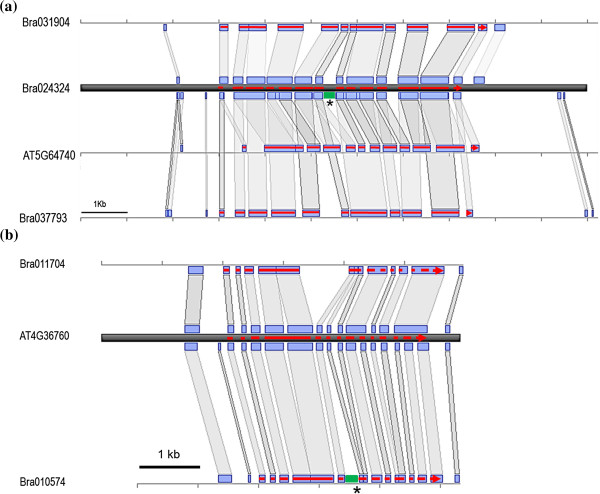

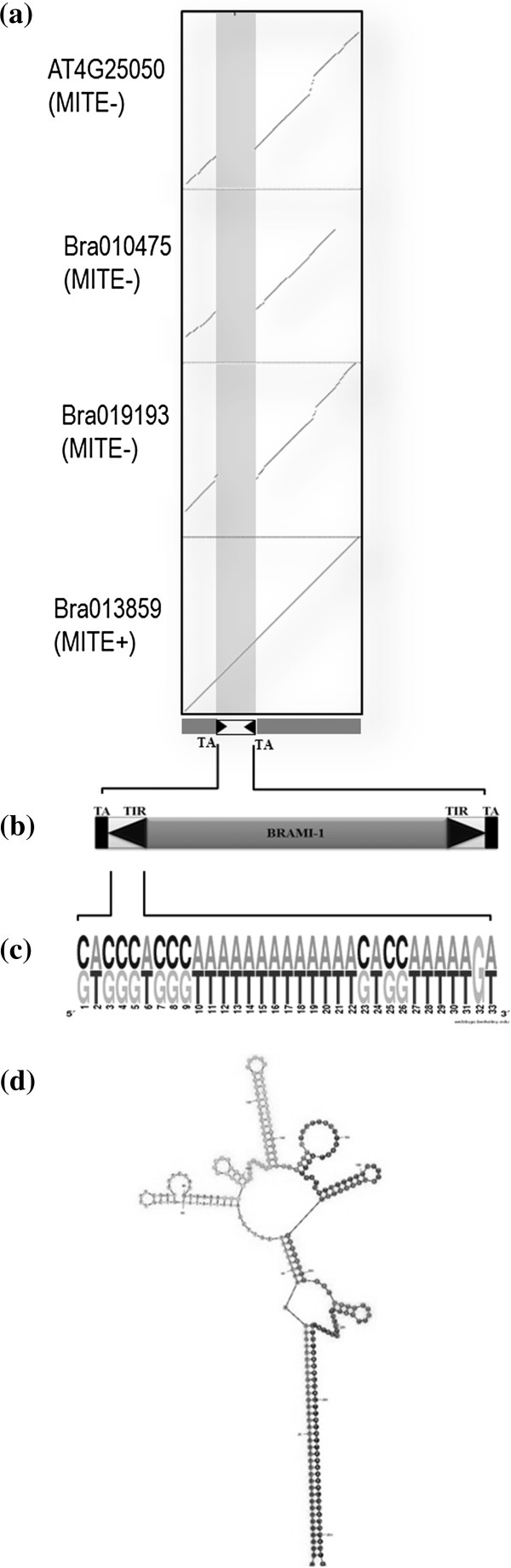

We identified a 260 bp MITE in the Brassica rapa BAC clone, KBrB059A03 using MUST, a de novo program for MITE identification, and additional manual inspection. MITE characterization on B. rapa contig (KBrB059A03) using MUST yielded 291 candidate MITEs and further careful manual inspection of each candidate MITE for TIR and TSD using self-BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) led to the identification of BRAMI-1. Comparison of BRAMI−1 against the repeat database (http://www.girinst.org/) showed 77% similarity to a reported Stowaway MITE, ATTIRTA-1 in A. thaliana[29]. Perfect MITE insertion was confirmed by comparing one of the representative B. rapa genes (Bra013859) harboring a BRAMI-1 insertion with the related empty sites in its non-insertion paralogs (NIPs) (Bra010475 and Bra019193) from B. rapa syntenic blocks and its ortholog (At4g25050) in A. thaliana (Figure 1a, b). The MITE included 33 bp of highly conserved A/T rich (>69%) TIRs and was flanked with a unique di-nucleotide TA target site duplication (TSD), which are distinct characteristics of the Stowaway super-family MITEs (Figure 1b, c). The secondary structure of the MITE was predicted using mfold (Figure 1d), which showed a potential DNA hairpin-like secondary structure.

Figure 1.

Identification and characterization of the BRAMI-1 elements. (a) Dotplot analysis of Bra013859 and the related empty sites in its two non-insertion paralog (NIP) genes, Bra019193 and Bra010475 from B. rapa and its orthologue At4g25050 from A. thaliana (b) The structure of BRAMI-1 showing its characteristic properties, TA Target site duplication (c) Conserved 33 bp TIR sequences shown by Weblogo analysis (d) Hypothetical secondary structure and expected loop formation predicted by mfold.

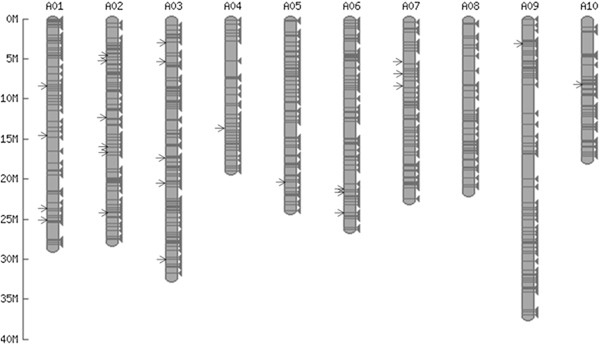

BLASTn searches revealed a total of 697 BRAMI-1 elements in the 256 Mb B. rapa genome sequence. In silico mapping of these elements on the B. rapa pseudo-chromosomes showed that they were evenly distributed in the euchromatin regions of the B. rapa genome (Figure 2). The physical positions of the 697 BRAMI-1 elements in the B. rapa genome are listed in Additional file 1. On average, 70 BRAMI-1 elements were found on each pseudo-chromosome. MITE density analysis (chromosome size/no. of MITEs per chromosome) shows chromosome 3 (31.72 Mb), which is the second largest in size, has the high MITE density (MITE/0.28 Mb), while the largest chromosome 9 (37.12 Mb) had the less MITE density (MITE/0.44 Mb).

Figure 2.

In silico mapping of BRAMI-1 elements in 256 Mb of B. rapa pseudo-chromosomes. Arrows indicate the positions of the 25 members used for MIP analysis. The exact physical positions of the 697 BRAMI-1 members are listed in Additional file 1.

We found 516 and 15 copies in 470 Mb of B. oleracea and 15 Mb of B. napus shotgun sequences, respectively. Based on this, the total numbers of the BRAMI-1 MITE members were estimated as 1440, 1464 and 2490 in the whole genomes of B. rapa, B. oleracea and B. napus, respectively (Table 1). By contrast, in A. thaliana we found only 70 copies of ATTIRTA-1, the closest Arabidopsis relative of BRAMI-1. Simple comparison revealed that the copy numbers of these MITEs in Brassica genomes are 20–35 times more than that of Arabidopsis.

Table 1.

Summary of observed and predicted copy numbers of the BRAMI-1 elements in Brassica relatives

|

MITE |

BRAMI-1 |

ATTIRTA-1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. oleracea | B. rapa | B. napus | A. thaliana | |

| Database type |

GSS |

Pseudo-chromosomes |

GSS |

Whole genome |

| Database size |

470 Mb |

256 Mb |

15 Mb |

119 Mb |

| Total copies |

399 |

697 |

11 |

70 |

| (>80% similarity) |

123 |

401 |

4 |

34 |

| Average length of the GSS sequence |

700 bp |

N/A |

700 bp |

N/A |

| Estimated Genome Size [30] |

696 Mb |

529 Mb |

1132 Mb |

157 Mb |

| Estimated copies in the whole genome | 1464 | 1440 | 2490 | 44 |

BLASTn was performed at the local database (http://imcrop.snu.ac.kr).

N/A: not applicable.

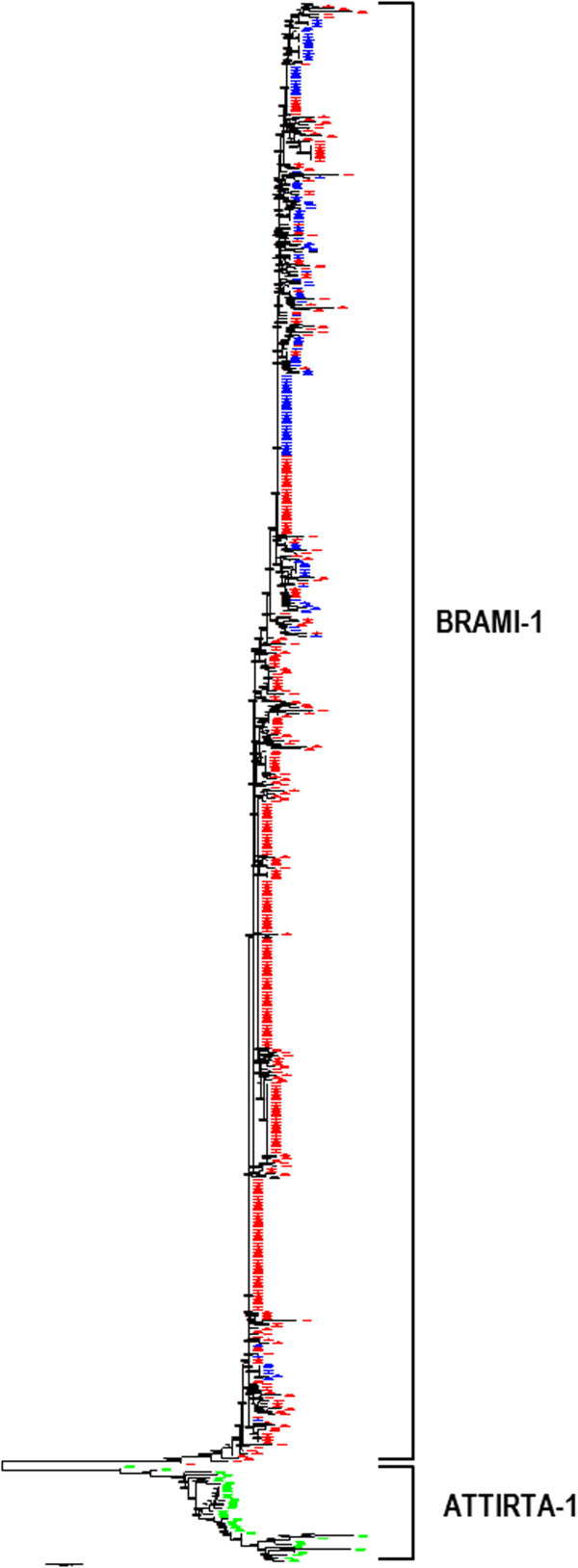

Phylogenetic analysis of the BRAMI-1 elements

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted for 528 nearly intact MITE members that have >80% similarity to BRAMI-1: 401 members from B. rapa, 123 from B. oleracea, and four from B. napus. In addition, 34 ATTIRTA-1 members from A. thaliana were included. The ATTIRTA-1 members formed a separate clade from the Brassica members, and they were very diverse among themselves. By contrast, BRAMI-1 members from the three Brassica species were highly conserved and were interspersed with each other (Figure 3) indicating they were rapidly amplified in the Brassica genome after divergence from Arabidopsis. Due to their high sequence similarity, we could not distinguish any separate clades for the BRAMI-1 family members in the Brassica species.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of BRAMI-1 elements from Brassica species and ATTIRTA-1 fromA. thaliana. Relatively intact MITE members showing 80% similarity to the characteristic MITE structure were used for the analysis. A total of 528 BRAMI-1 members including 401, 123, and 4 from B. rapa (red), B. oleracea (blue), and B. napus (black), respectively, and 34 ATTIRTA-1 members (green) were compared. Sequence alignment was conducted using ClustalW and then the phylogenetic tree was generated using the neighbor joining method with 500 bootstrap replicates.

BRAMI-1 insertion in genic regions of the B. rapa genome

We inspected the insertion sites of the 697 BRAMI-1 elements in the B. rapa genome using the annotated B. rapa genome database [31]. The analysis showed that 548 members (78.6%) were located in gene-rich regions, less than 3 kb from genes. Among them, 71 (10.2%) were inside the gene structure, specifically in introns, and 281 (40.3%) were within less than 1 kb of a gene (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the insertion positions of 697 BRAMI-1 elements in the B. rapa genome

| Insertion position | Number of elements | Percentage of elements |

|---|---|---|

| Gene |

71 |

10.2 |

| Near Genic Regions (<1 kb)a |

281 |

40.3 |

| Near Genic Regions (1 kb to <2 kb)a |

134 |

19.2 |

| Near Genic Regions (2 kb to <3 kb)a |

62 |

8.9 |

| Intergenic Region (>3 kb)a |

149 |

21.4 |

| Total | 697 | 100.0 |

a Distance from nearest gene.

We closely inspected the 71 genic insertions by comparing with their NIPs from triplicated chromosomal blocks. Similar numbers of insertions were identified in tri-, di-, and mono-copy genes (20, 26, and 24 insertions, respectively; Table 3) indicating that multi-copy genes did not preferentially contain BRAMI-1 insertions. Comparison of genes containing the BRAMI-1 insertion and their NIPs genes in the triplicated blocks revealed that all of the elements resided in intronic regions.

Table 3.

Insertion positions and names of the 71 genes harboring BRAMI-1 elements in intronic regions and list of their orthologous genes in Arabidopsis and NIPs in the triplicated blocks of the B. rapa genome

| |

MITE No |

Chr No |

MITE start |

MITE end |

Ortholog from A. thaliana |

Triplicated blocks inB. rapaz |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF | MF1 | MF2 | ||||||

| THREE COPY GENES |

23 |

A01 |

8110084 |

8109821 |

At4g25050 |

Bra013859 |

Bra019193 |

Bra010475 |

| |

83 |

A02 |

4177719 |

4177456 |

At5g17300 |

Bra008563 |

Bra006394 |

Bra023610 |

| |

176 |

A03 |

5778627 |

5778365 |

At5g55050 |

Bra002937 |

Bra035549 |

Bra028994 |

| |

188 |

A03 |

8910390 |

8910639 |

At2g37940 |

Bra005148 |

Bra017148 |

Bra000029 |

| |

219 |

A03 |

17370042 |

17370087 |

At3g15820 |

Bra027205 |

Bra021138 |

Bra001607 |

| |

220 |

A03 |

17370087 |

17370331 |

At3g15820 |

Bra027205 |

Bra021138 |

Bra001607 |

| |

299 |

A04 |

13405505 |

13405756 |

At2g30110 |

Bra018338 |

Bra021611 |

Bra022779 |

| |

303 |

A04 |

14136797 |

14136887 |

At2g31500 |

Bra018236 |

Bra021727 |

Bra022844 |

| |

346 |

A05 |

7674854 |

7674713 |

At2g29980 |

Bra018348 |

Bra021599 |

Bra022767 |

| |

347 |

A05 |

7674974 |

7675006 |

At2g29980 |

Bra018348 |

Bra021599 |

Bra022767 |

| |

349 |

A05 |

8733844 |

8733992 |

At4g04640 |

Bra029511 |

Bra000802 |

Bra018503 |

| |

368 |

A05 |

16917820 |

16918070 |

At3g20770 |

Bra035746 |

Bra023927 |

Bra001802 |

| |

425 |

A06 |

14973843 |

14973752 |

At5g64740 |

Bra024324 |

Bra037793 |

Bra031904 |

| |

443 |

A06 |

22195786 |

22196049 |

At3g28050 |

Bra025321 |

Bra033037 |

Bra039062 |

| |

450 |

A06 |

24123977 |

24123793 |

At2g01430 |

Bra024888 |

Bra026666 |

Bra017451 |

| |

452 |

A06 |

24666391 |

24666142 |

At5g46630 |

Bra025009 |

Bra022052 |

Bra017537 |

| |

473 |

A07 |

8537339 |

8537527 |

At1g22340 |

Bra031388 |

Bra012324 |

Bra016424 |

| |

474 |

A07 |

9114152 |

9114414 |

At1g20670 |

Bra025837 |

Bra012243 |

Bra016456 |

| |

566 |

A08 |

20712404 |

20712596 |

At1g07920 |

Bra018669 |

Bra031602 |

Bra030707 |

| |

654 |

A10 |

1570075 |

1569913 |

At1g06080 |

Bra015473 |

Bra032437 |

Bra030638 |

| TWO COPY GENES |

46 |

A01 |

18882651 |

18882770 |

At5g52140 |

Bra028293 |

Bra022579 |

- |

| |

55 |

A01 |

23626196 |

23626459 |

At3g16180 |

Bra027185 |

Bra021168 |

- |

| |

61 |

A01 |

25069244 |

25069502 |

At3g02180 |

- |

Bra021476 |

Bra001035 |

| |

87 |

A02 |

5079784 |

5080047 |

At5g20540 |

- |

Bra006563 |

Bra020109 |

| |

113 |

A02 |

9852697 |

9852644 |

At1g66370 |

Bra004162 |

Bra039763 |

- |

| |

153 |

A02 |

25486260 |

25486523 |

At5g23940 |

Bra009716 |

- |

Bra029388 |

| |

168 |

A03 |

2298612 |

2298349 |

At5g12420 |

- |

Bra006160 |

Bra023377 |

| |

200 |

A03 |

11193078 |

11192830 |

At2g47460 |

Bra004456 |

- |

Bra000453 |

| |

234 |

A03 |

20936196 |

20936267 |

At5g23260 |

Bra013028 |

Bra026507 |

Bra029365 |

| |

235 |

A03 |

20936271 |

20936494 |

At5g23260 |

Bra013028 |

Bra026507 |

Bra029365 |

| |

249 |

A03 |

24785451 |

24785715 |

At4g22950 |

- |

Bra019343 |

Bra020826 |

| |

319 |

A04 |

18584148 |

18584406 |

At2g45550 |

Bra004921 |

Bra039330 |

- |

| |

444 |

A06 |

22352521 |

22352784 |

At3g27640 |

Bra025293 |

- |

Bra039073 |

| |

460 |

A07 |

1577014 |

1576769 |

At2g18230 |

Bra039627 |

- |

Bra037229 |

| |

467 |

A07 |

6402416 |

6402153 |

At1g29120 |

- |

Bra030121 |

Bra010851 |

| |

490 |

A07 |

12392864 |

12392917 |

At3g57530 |

Bra007334 |

- |

Bra003287 |

| |

536 |

A08 |

12108300 |

12108552 |

At4g35150 |

- |

Bra017699 |

Bra034678 |

| |

545 |

A08 |

15271728 |

15271631 |

At4g36760 |

Bra011704 |

- |

Bra010574 |

| |

596 |

A09 |

8214071 |

8213980 |

At1g61890 |

Bra027073 |

Bra028379 |

- |

| |

597 |

A09 |

8214185 |

8214078 |

At1g61890 |

Bra027073 |

Bra028379 |

- |

| |

604 |

A09 |

16501688 |

16501868 |

At5g46350 |

Bra025021 |

Bra022033 |

Bra017561 |

| |

605 |

A09 |

16667316 |

16667053 |

At5g46040 |

- |

Bra022016 |

Bra017582 |

| |

606 |

A09 |

16682960 |

16683223 |

At5g46040 |

- |

Bra022016 |

Bra017582 |

| |

608 |

A09 |

19871591 |

19871427 |

At1g32780 |

Bra023290 |

Bra010185 |

- |

| |

615 |

A09 |

24192808 |

24192545 |

At1g23380 |

Bra024593 |

- |

Bra016348 |

| |

666 |

A10 |

8067999 |

8067852 |

At5g57655 |

Bra002710 |

Bra020426 |

- |

| |

670 |

A10 |

8789727 |

8789464 |

At5g59340 |

Bra002576 |

Bra020321 |

- |

| ONE COPY GENES |

40 |

A01 |

14766344 |

14766081 |

- |

- |

- |

Bra029909 |

| |

41 |

A01 |

14767003 |

14766741 |

- |

- |

- |

Bra029909 |

| |

129 |

A02 |

16530545 |

16530808 |

At4g01590 |

- |

- |

Bra008554 |

| |

178 |

A03 |

5992774 |

5992961 |

- |

- |

- |

Bra029035 |

| |

223 |

A03 |

18448338 |

18448491 |

At3g20360 |

- |

- |

Bra001785 |

| |

578 |

A09 |

3996947 |

3996684 |

At2g11810 |

- |

- |

Bra037199 |

| |

266 |

A03 |

29733949 |

29734212 |

- |

- |

Bra017680 |

- |

| |

268 |

A03 |

30599723 |

30599787 |

At4g36940 |

- |

Bra017808 |

- |

| |

472 |

A07 |

7616363 |

7616100 |

- |

- |

Bra012436 |

- |

| |

49 |

A01 |

21397784 |

21397864 |

At3g19870 |

- |

Bra038237 |

- |

| |

120 |

A02 |

12485621 |

12485884 |

At1g72110 |

- |

Bra008008 |

- |

| |

128 |

A02 |

15935110 |

15935361 |

At1g80200 |

- |

Bra008487 |

- |

| |

148 |

A02 |

24005490 |

24005690 |

- |

- |

Bra020642 |

- |

| |

285 |

A04 |

7140471 |

7140542 |

- |

Bra028251 |

- |

- |

| |

378 |

A05 |

20048141 |

20048392 |

- |

Bra027271 |

- |

- |

| |

445 |

A06 |

22716443 |

22716194 |

At3g26610 |

Bra025216 |

- |

- |

| |

501 |

A07 |

16958538 |

16958801 |

At1g65590 |

Bra004121 |

- |

- |

| |

513 |

A07 |

20340243 |

20340188 |

At1g74790 |

Bra015893 |

- |

- |

| |

655 |

A10 |

4270200 |

4270396 |

At1g02390 |

Bra033323 |

- |

- |

| |

656 |

A10 |

4270415 |

4270484 |

At1g02390 |

Bra033323 |

- |

- |

| |

657 |

A10 |

4410198 |

4410053 |

- |

Bra033297 |

- |

- |

| |

672 |

A10 |

9364412 |

9364675 |

- |

Bra002467 |

- |

- |

| |

673 |

A10 |

9364744 |

9365007 |

- |

Bra002467 |

- |

- |

| 677 | A10 | 10858935 | 10858966 | - | Bra002214 | - | - | |

z The triplicated chromosome blocks are denoted according to the classification of the B. rapa genome annotation databases (BRAD) [25,31]. The triplicated chromosome blocks are classified as one least fractionized block (LF) and two moderately fractionized blocks (MF1, MF2). Genes with BRAMI-1 insertion in introns are denoted in bold and their NIPs are denoted in plain letters.

For example, Bra024324 gene was annotated as having 13 exons and included the BRAMI-1 insertion in the 7th intron. Its two NIPs (Bra031904, Bra037793) and its Arabidopsis ortholog (At5g64740, CELLULOSE SYNTHASE 6) have similar structures in which the exonic regions share conserved sequences with Bra024324 (Figure 4a). Another gene, Bra010574, which has the BRAMI-1 insertion in 5th intron, showed conserved CDS sequences without any change of gene structure compared to its NIPs (Bra011704) and its Arabidopsis ortholog (At4g36760, 15 ORF, N-1-NAPHTHYLPHTHALAMIC ACID BINDING PROTEIN) (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Microsynteny between the genomic regions with BRAMI-1 insertions and homologous blocks in B. rapa and A. thaliana. (a) Genomic region including 3 kb upstream from the start codon and 3 kb downstream from the stop codon of Bra024324 compared with those of its two paralogs and Arabidopsis ortholog. (b) Genomic region including 2 kb upstream from the start codon and 0.3 kb downstream from the stop codon of Bra010574 compared with those of its paralog and Arabidopsis ortholog. Genomic organization, such as exon and intron location, is based on annotation information in BRAD for B. rapa and TAIR for A. thaliana. Red lines indicate exons of each gene annotation. The gray bars connecting boxes on genome sequences indicate synteny blocks present in both sequences. The position of the MITE insertion is indicated by both an asterisk and a green block. The map was generated based on nucleotide sequence similarity determined by BLASTn search.

Transcriptional changes of B. rapa genes containing BRAMI-1 insertions

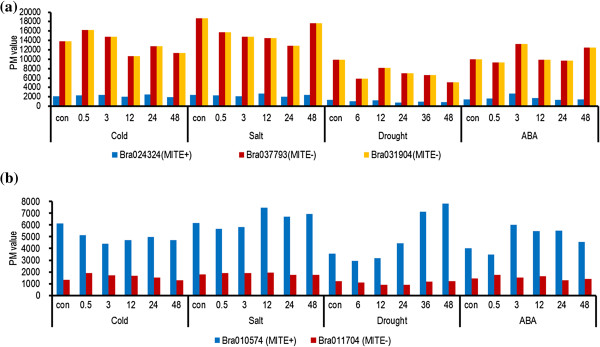

Even though most of the BRAMI-1 insertions were found in introns or UTRs, some modification of gene expression might still be mediated by BRAMI-1. Therefore, we analyzed expression level changes by comparison to NIPs using a B. rapa microarray database. Among the 46 multicopy genes with BRAMI-1 insertions (20 tri-copy genes and 26 di-copy genes), only six were present along with their NIPs in the microarray database. Of the six genes with BRAMI-1 insertions, only Bra039627 showed similar expression to that of its NIPs, regardless of stress treatments. One gene, Bra024324, showed decreased expression and four genes, Bra027185, Bra039330, Bra034678, and Bra010574, showed increased expression compared to that of their NIPs (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of expression profiles between genes with BRAMI-1 insertions and their NIPs. (a) Expressions of Bra024324 and its two NIPs, Bra031904 and Bra037793, were analyzed by searching a microarray database of B. rapa treated with cold (4°C), salt (250 mM NaCl), drought (air-drying), or ABA (100 μM). (b) Expression of Bra010574 and its NIP, Bra011704, were compared. MITE+ and MITE- indicate genes with the BRAMI-1 insertion and their NIPs, respectively.

The expression of Bra024324, which contains a BRAMI-1 insertion, was severely decreased compared to that of its NIPs, Bra031904 and Bra037793, under normal conditions and also under the four stress treatment conditions, indicating that Bra024324 gene expression was maintained at a very low level even though the BRAMI-1 insertion did not affect exons (Figure 5a). By contrast, expression of Bra010574, with a BRAMI-1 insertion, was more than 3-fold higher than expression of its NIP Bra011704 under control and all four treatment conditions (Figure 5b).

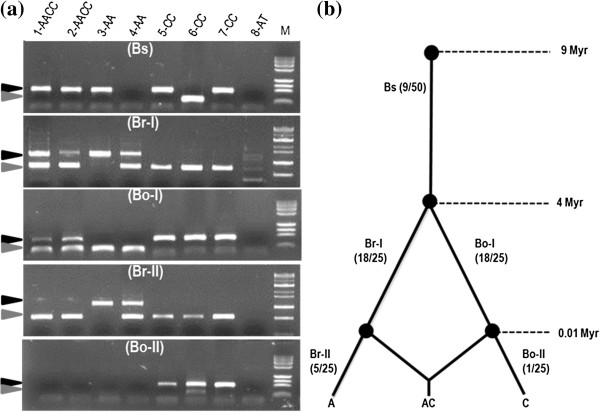

Survey of MITE insertion polymorphisms (MIPs) and estimation of activation dates

To analyze BRAMI-1’s transposition activity and insertion time, we designed 50 MIP primers, 25 for B. rapa and 25 for B. oleracea, from the flanking regions of the BRAMI-1 insertions, especially insertions in genic regions (Additional file 2). The positions of the 25 B. rapa MIPs are denoted as arrows on the in silico map (Figure 2). Almost all of the primer pairs revealed polymorphisms (48 in 50 pairs; 96%) among seven accessions belonging to three Brassica species, indicating that the BRAMI-1 members have been continuously activated during diversification of the Brassica genome. Moreover, there was high polymorphism within species, with seven (14%), six (12%), and ten (20%) polymorphisms among two accessions of B. napus, two accessions of B. rapa, and three accessions of B. oleracea, respectively.

We grouped the 50 MIPs into three different groups: Bs (common to both species), Br (B. rapa-unique), and Bo (B. oleracea-unique), to deduce the tentative insertion times (Figure 6a). The Br and Bo MIPs were further classified into two subgroups, -I and –II, based on the presence or absence of the insertion in their allopolyploid species B. napus. Among the 25 B. rapa MIPs, 3, 17, and 5 were Bs, Br-I, and Br-II type insertions, respectively, and among the 25 B. oleracea MIPs, 6, 18, and 1 were Bs, Bo-I, and Bo-II types, respectively. Overall, 18% were shared in the Brassica genus, and 82% were species-unique insertions (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

MITE insertion polymorphism (MIP) analysis and estimation of insertion time. MIP patterns were classified into 5 groups (Bs, Br- I, II and Bo- I, II), based on existence of MIPs between species. (a) Gel electrophoresis of five MIPs (Bo-23, Br-6, Br-3, Bo-10, Bo-21, ordered from the top, for more information on the MIP IDs refer to Additional file 2). The lane numbers (1 to 8) indicate plant materials used, as described in Table 1. A, C, and AC represent the genomes of B. rapa, B, oleracea, and B. napus, respectively. AT indicates A. thaliana. M, molecular size marker. The presence or absence of an insertion is denoted by a black or gray arrowhead, respectively. (b) Estimated insertion timing for the five MIP groups during the evolution of Brassica species [27,36,37].The number within the parentheses indicates the corresponding number of MITE members belonging to the particular group (based on the analysis in panel a).

Phylogenetic analysis based on the 50 MIP profiles revealed four distinct clusters at the 0.30 genetic similarity coefficient level (Additional file 3). Arabidopsis was separated from Brassica accessions with a genetic similarity coefficient of 0.16. Three Brassica species each formed a distinct cluster with two or three accessions belonging to each species, corresponding well with the phylogeny of Brassica species. Each MIP reflects the insertion time at that genomic position and thus MIP-based genotyping and phylogenetic analysis will be a good tool for study of genetic diversity in the Brassica genus. We also confirmed that the MIPs are clearly distinguishable on agarose gels, heritable and reproducible, characteristics beneficial as DNA markers. A MIP between two B. oleracea accessions, Bo-19, segregated according to a normal Mendelian 1: 2: 1 ratio in a survey of 94 F2 progeny of a cross between the two accessions (Additional file 4).

Discussion

Structure, distribution and evolution of BRAMI-1 in the B. rapa genome

BRAMI-1 exhibits the basic characteristics of conventional Stowaway-like MITEs, which include small size, TIRs, and TSDs, and also possesses a potential DNA hairpin-like secondary structure. BRAMI-1 elements have a highly conserved 33 bp TIR region that is rich in A + T nucleotides (>69%) and a 194 bp internal region. In plants, most MITEs are classified as either Tourist-like or Stowaway-like. Tourist-like MITEs are regarded as deletion derivatives of full-length autonomous TEs, such as mPing derived from Pong and PIF[13,32,33]. The origin of Stowaway-like MITEs is unclear due to the lack of sufficient sequence similarity to known autonomous TEs [1,34]. However, numerous Stowaway-like MITEs can be cross-mobilized by distantly related Mariner-like elements (MLEs) to generate high copy numbers [13,35]. However, we could not identify the trans-acting autonomous element for the BRAMI-1 elements in this study.

Rapid amplification of BRAMI-1 elements in the Brassica genus

The genus Brassica is an excellent model plant to study polyploidization-mediated genome evolution because allotetraploid species like B. juncea, B. napus, and B. carinata evolved very recently from the three diploid species B. rapa, B. oleracea, and B. nigra, and even the diploid Brassica species have triplicated genome features that arose approximately 13 million years ago (MYA) [26,27,36]. The estimated copy numbers of the BRAMI-1 elements were similar in two closely related Brassica species: 1440 and 1464 in B. rapa and B. oleracea, respectively supporting that BRAMI-1 elements were actively amplified in both Brassica species [27,36,37]. This is the first MITE found to exhibit very high copy numbers in Brassica, although one medium copy number Brassica Stowaway MITE, named Brasto, was recently characterized [38].

BRAMI-1 shares 77% similarity with the A. thaliana MITE ATTIRTA-1, suggesting that they evolved from a common ancestor of the Brassica and Arabidopsis lineage. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that ATTIRTA-1 and BRAMI-1 elements have clearly different evolutionary histories. The ATTIRTA-1 elements showed a high amount of variation even though their copy numbers were small compared to those of the BRAMI-1 members, indicating that the ATTIRTA-1 members were maintained in the Arabidopsis genome without further amplification after the split from the Brassica lineage 13–17 MYA [27,36]. By contrast, members derived from B. rapa (red), B. oleracea (blue), and B. napus (black) are highly conserved and interrelated with each other, demonstrating that the members were actively amplified in the Brassica lineage after divergence from Arabidopsis (Figure 3). This is consistent with a report showing highly active TE amplification in B. oleracea[28]. We assume that several transpositional bursts may have been responsible for the amplification of the BRAMI-1 members in the Brassica lineage [16,39,40].

The putative role of BRAMI-1 in B. rapa genome evolution

There have been many reports of MITEs involved in the evolution of genes and genomes. MITEs are often inserted in genic regions such as promoter regions, UTRs, introns, or exons and can influence the expression of genes [1,2,16,19,34]. MITE insertion into the various functional regions of a gene can modify its transcriptional activity, cause silencing, and up- or down-regulation of gene expression [34,41]. We found 697 BRAMI-1 elements were dispersed across the whole genome (Figure 2). A total of 626 members (90%) were identified in 177 Mb of intergenic spaces and 71 members (10%) were identified in 79 Mb of gene spaces in the 256 Mb B. rapa pseudo chromosome sequences. Among the 697 elements, 548 members (78.6%) were located within 3 kb of genic regions and all the 71 copies found in genic regions were resided in introns. The 33 Mb intronic regions exhibited 65% A + T composition, which was much higher than that of 46 Mb exonic regions (54% A + T composition). This insertion target site preference for non-coding sequences of genic regions is similar to the insertion preference of mPing in rice, which is more often found in A + T rich non-coding sequence than in G + C rich exonic regions [19].

We showed that BRAMI-1 insertion might be one of the causal forces for modification of gene expression. When we compared the expressions of several genes harboring BRAMI-1 within their genic regions with those of NIPs, most of the genes with BRAMI-1 insertions showed different expression patterns than their NIP counterparts (Figure 5). Comparison of microsynteny between regions with BRAMI-1 insertions and their non-insertion homologous genes in B. rapa and A. thaliana showed relatively conserved coding sequences but more sequence variation in introns and UTRs, including from the BRAMI-1 insertions (Figure 4). The observed changes in transcription levels might arise from BRAMI-1 insertions into intronic or UTR regions, similar to a recent report showing an enhancing effect of mPing near rice genes [19]. Further intensive study of whole transcriptome profiles will be necessary to address MITE effects on gene expression.

BRAMI-1 elements are active up to the present in Brassica genera

MIP patterns showing insertions specific to certain species or accessions elucidate the timing of insertion events. Among 50 MIPs, nine (18%) BRAMI-1 elements were found in both B. rapa and B. oleracea, indicating that they were inserted into the regions before B. rapa and B. oleracea diverged from each other 4 MYA [27,36]. The other 41 (82%) were unique to one species or the other, indicating they were inserted after the divergence of the two lineages. Among the 41 species-specific members, six (8%) showed no insertion in B. napus (the allopolyploid product of B. rapa and B. oleracea) indicating that they inserted into each genome after allopolyplidization 0.01 MYA [36] (Figure 6). Some MIPs were found between accessions of same species, and the MIPs segregated normally in an F2 population, opening a new window for MIP-based marker development for marker-assisted selection and other breeding applications in Brassica crops. Overall, the MIPs revealed that BRAMI-1 elements were gradually inserted into the Brassica genome during various events and remained active up to the present.

Conclusions

We characterized a high copy Stowaway family MITE, named as BRAMI-1, in three Brassica crops and showed its putative role in the evolution of the highly duplicated Brassica genome based on comparative genomics analysis. MIP analysis revealed that the BRAMI-1 elements were dispersed into whole Brassica genome by gradual amplification. We also propose effective utilization of the elements as DNA markers for breeding and evolution of duplicated genes.

Methods

Identification and characterization of BRAMI-1

We analyzed a repeat-rich B. rapa BAC clone sequence, KBrB059A03 (AC189406), to find high copy repeat elements using MUST, a de novo program for MITE analysis, with the default parameters [42]. The BAC clone contained 139 kb of highly repetitive sequence. The structure of the TIRs was analyzed using weblogo [43]. The hypothetical DNA hairpin-like structure was predicted using the mfold application [44].

The new MITE was used as a query to retrieve its family members from a local database (http://im-crop.snu.ac.kr/) that includes 256 Mb of 10 pseudo-chromosome sequences from B. rapa, 425 Mb of B. oleracea shotgun sequences, 15 Mb of B. napus shotgun sequences, and the whole genome sequence of A. thaliana, using the approach suggested by Wicker et al. (2007) [10]. BLASTn with default parameters [45] and a threshold E-value of 1E-10 was employed to search for MITE family members. The insertion sites of 697 elements and their flanking regions were annotated using the B. rapa genome database [31].

Estimation of copy number

The copy number of BRAMI-1 in the B. rapa genome (529 Mb) was estimated from the number of copies identified in 256 Mb of 10 pseudo-chromosome sequences from B. rapa[25]. The copy numbers in the B. oleracea and B. napus genomes were estimated by considering the hit numbers in the available genome shotgun sequences. A total of 425 Mb of B. oleracea sequences derived from 680,894 genome shotgun sequences with an average length of 700 bp [46] and 15 Mb of B. napus shotgun sequences derived from 52,099 genome shotgun sequences (GSS) with an average length of 700 bp were downloaded from GenBank (NCBI) and used as local databases. The copy numbers of BRAMI-1 in B. oleracea and B. napus were estimated using the previously reported formula [28]: [(1/genome coverage)/2] x number of hits {[1 + [(average GSS) -TIR length x2)/(average GSS length + TIR length x2)]}. Relatively intact copies with more than 80% coverage of the BRAMI-1 structure were collected from the three Brassica species for phylogenetic analysis. Multiple sequence alignment was conducted using ClustalW and phylogenetic analysis was performed based on the neighbor joining method in MEGA5 [47]. In A. thaliana, ATTIRTA-1 was the most closely related element to BRAMI-1, so it was included in the phylogenetic analysis. Tree topologies were evaluated using bootstrap analysis with 500 replicates for the neighbor-joining method [47].

Expression analysis of B. rapa genes with BRAM1-1 insertions

We investigated expression modification of genes that had a MITE insertion inside of the gene structure by comparison with their syntenic paralogs using a 24 K microarray database (http://nabic.rda.go.kr) [48]. The microarray database represented ca. 24,000 unigenes generated from cDNA libraries of B. rapa ssp. pekinensis (inbred line ‘Chiifu’) and provided transcriptome profiling of changes induced by abiotic stress treatment. A given probe sequence and its ID in the microarray were searched using the coding sequence of the gene as a query. The perfect match (PM) values of probes were retrieved and processed to identify expression patterns, as described previously [48].

MITE Insertion polymorphism (MIP)

To inspect insertion polymorphisms and thus infer activation times, we used seven Brassica accessions belonging to three species and A. thaliana ecotype Columbia (Table 4). DNA was extracted from fresh leaf samples using the CTAB method [49]. In addition, a total of 94 F2 progeny from a cross between B. oleracea accessions C1234 and C1184 were used for segregation pattern analysis of MIPs.

Table 4.

Plant materials used for MIP analysis

| Genome | Species | Accessions (cultivars) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

AACC |

B. napus |

Tapidor |

| 2 |

AACC |

B. napus |

Ningyou7 |

| 3 |

AA |

B. rapa |

Chiifu |

| 4 |

AA |

B. rapa |

Kenshin |

| 5 |

CC |

B. oleracea |

C1234 |

| 6 |

CC |

B. oleracea |

C1184 |

| 7 |

CC |

B. oleracea |

C1235 |

| 8 | AT | A. thaliana | Columbia |

We designed 50 primer pairs, 25 using shotgun sequences of B. oleracea (Bo 1–25) and 25 using the B. rapa pseudo-chromosome sequences (Br 1–25), from the flanking sequences of BRAM1-1 insertion sites using the Primer3 software program [50] (Additional file 2). PCR was conducted in 20 μL total volume containing 10 ng DNA, 10 pmol each primer, 250 μM dNTPs, and 1 unit Taq DNA polymerase (VIVAGEN, Republic of Korea). PCR conditions were as follows: 5 min at 94°C, 38 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 56°C-62°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 60 sec, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min, using a MG96G thermo cycler (LongGene Scientific Instruments, China). PCR products were analyzed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized on a UV trans-illuminator after ethidium bromide staining.

For MIP marker analysis, each band was scored as ‘1’ or ‘0’ for presence or absence, respectively. Jaccard’s similarity coefficient and a dendrogram of the genetic relationship according to Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Average (UPGMA) analysis were determined by the NTSYS-pc program (Numerical Taxonomy & Multivariate Analysis System) [51].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

PS and TJY initiate the research. PS, SCL, JL, and NKI carried out the molecular experiments, interpreted the results. PS and BSC performed the bioinformatics analyses. MJ and BSP provided suggestion for the manuscript preparation and writing. PS and TJY wrote the manuscript. All authors critically read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Physical position of the 697 members in the B. rapa genome.

List of Primers used for MITE insertion polymorphism analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis of MIPs. Dendrogram based on Jaccard’s similarity coefficient of 50 MIPs among eight genotypes constructed using the UPGMA method.

MIP survey of 94 B. oleracea F2 plants from a cross between parental lines C1234 (P1) and C1184 (P2). The primer MIP-M1-19 was used and a ratio of 22:50:21 was observed for genotypes P1: P1/P2 : P2.

Contributor Information

Perumal Sampath, Email: sampathsnu@snu.ac.kr.

Sang-Choon Lee, Email: sclee0923@hanmail.net.

Jonghoon Lee, Email: jonghoonlee@snu.ac.kr.

Nur Kholilatul Izzah, Email: lila_ref@yahoo.co.id.

Beom-Soon Choi, Email: euphra@snu.ac.kr.

Mina Jin, Email: genemina@korea.kr.

Beom-Seok Park, Email: pbeom@rda.go.kr.

Tae-Jin Yang, Email: tjyang@snu.ac.kr.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program (No. 309008–05) for Agriculture and Forestry, Ministry of Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Republic of Korea and and a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (No. PJ0090762012), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. Perumal Sampath is supported by a Korean Government Scholarship (KGSP) 2008 from the National Institute for International Education (NIIED), Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, Republic of Korea.

References

- Feschotte C, Jiang N, Wessler SR. Plant transposable elements: where genetics meets genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(5):329–341. doi: 10.1038/nrg793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte C. Transposable elements and the evolution of regulatory networks. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(5):397–405. doi: 10.1038/nrg2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer G, Young S, Bharti AK, Gundlach H, Raymond C, Fuks G, Butler E, Wing RA, Rounsley S, Birren B. Structure and architecture of the maize genome. Plant Physiol. 2005;139(4):1612–1624. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.068718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiel JL, Blot M. Transposable elements and fitness of bacteria. Theor Popul Biol. 2002;61(4):509–518. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2002.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell PL, Buckler ES, Ross-Ibarra J. Crop genomics: advances and applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;13(2):85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrg3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel P, Gaut BS, Tikhonov A, Nakajima Y, Bennetzen JL. The paleontology of intergene retrotransposons of maize. Nat Genet. 1998;20(1):43–45. doi: 10.1038/1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable PS, Ware D, Fulton RS, Stein JC, Wei F, Pasternak S, Liang C, Zhang J, Fulton L, Graves TA. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326(5956):1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto TWJ, Kanamori H. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005;436(7052):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nature03895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker T, Sabot F, Hua-Van A, Bennetzen JL, Capy P, Chalhoub B, Flavell A, Leroy P, Morgante M, Panaud O. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(12):973–982. doi: 10.1038/nrg2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau TE, Wessler SR. Tourist: a large family of small inverted repeat elements frequently associated with maize genes. Plant Cell. 1992;4(10):1283–1294. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z. Eight novel families of miniature inverted repeat transposable elements in the African malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(4):1699–1704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Feschotte C, Zhang X, Wessler SR. Using rice to understand the origin and amplification of miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs) Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7(2):115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki N, Yano K, Okumoto Y, Tsukiyama T, Teraishi M, Tanisaka T. A genome-wide view of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) in rice rice, Oryza sativa ssp japonica. Genes Genet Syst. 2008;83(4):321–329. doi: 10.1266/ggs.83.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjak A, Boue S, Forneck A, Casacuberta JM. Recent amplification and impact of MITEs on the genome of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Genome Biol Evol. 2009;1:75–84. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Chen J, Zhang Y, Hu Q, Su W, Kuang H. Miniature Inverted–Repeat Transposable Elements (MITEs) Have Been Accumulated through Amplification Bursts and Play Important Roles in Gene Expression and Species Diversity in Oryza sativa. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(3):1005–1017. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo YJ, Kim KY, Shin WC, Lee GM, Ko JC, Nam JK, Kim BK, Ko JK, Yu Y, Yang TJ. Characterization of Imcrop, a Mutator-like MITE family in the rice genome. Genes Genomics. 2012;34(2):189–198. doi: 10.1007/s13258-011-0193-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Lee YH, Jiang Y, Shi X, Kertbundit S, Hall TC. A two-edged role for the transposable element Kiddo in the rice ubiquitin2 promoter. Plant Cell. 2005;17(5):1559–1568. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.030528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito K, Zhang F, Tsukiyama T, Saito H, Hancock CN, Richardson AO, Okumoto Y, Tanisaka T, Wessler SR. Unexpected consequences of a sudden and massive transposon amplification on rice gene expression. Nature. 2009;461(7267):1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/nature08479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piriyapongsa J, Jordan IK. Dual coding of siRNAs and miRNAs by plant transposable elements. RNA. 2008;14(5):814–821. doi: 10.1261/rna.916708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang H, Padmanabhan C, Li F, Kamei A, Bhaskar PB, Ouyang S, Jiang J, Buell CR, Baker B. Identification of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) and biogenesis of their siRNAs in the Solanaceae: new functional implications for MITEs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):42–56. doi: 10.1101/gr.078196.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisch D, Bennetzen JL. Transposable element origins of epigenetic gene regulation. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14(2):156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casa AM, Brouwer C, Nagel A, Wang L, Zhang Q, Kresovich S, Wessler SR. The MITE family heartbreaker (Hbr): molecular markers in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(18):10083–10089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons M, Cardle L, Rostoks N, Waugh R, Flavell AJ. Isolation, analysis and marker utility of novel miniature inverted repeat transposable elements from the barley genome. Molecular genetics genomics. 2008;280(4):275–285. doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang H, Wang J, Sun R, Wu J, Liu S, Bai Y, Mun JH, Bancroft I, Cheng F. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/ng.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TJ, Kim JS, Kwon SJ, Lim KB, Choi BS, Kim JA, Jin M, Park JY, Lim MH, Kim HI. Sequence-level analysis of the diploidization process in the triplicated FLOWERING LOCUS C region of Brassica rapa. Plant Cell. 2006;18(6):1339–1347. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun JH, Kwon SJ, Yang TJ, Seol YJ, Jin M, Kim JA, Lim MH, Kim JS, Baek S, Choi BS. Genome-wide comparative analysis of the Brassica rapa gene space reveals genome shrinkage and differential loss of duplicated genes after whole genome triplication. Genome Biol. 2009;10(10):R111. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-r111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wessler SR. Genome-wide comparative analysis of the transposable elements in the related species Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica oleracea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(15):5589–5594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401243101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. Molecular paleontology of transposable elements from Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetica. 1999;107(1–3):27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JS, Pepper AE, Hall AE, Chen ZJ, Hodnett G, Drabek J, Lopez R, Price HJ. Evolution of genome size in Brassicaceae. Ann Bot. 2005;95(1):229–235. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Shengyi L, Jian W, Lu F, Silong S, Bo L, Pingxia L, Wei H, Xiaowu W. BRAD, the genetics and genomics database for Brassica plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11(136):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Bao Z, Zhang X, Hirochika H, Eddy SR, McCouch SR, Wessler SR. An active DNA transposon family in rice. Nature. 2003;421(6919):163–167. doi: 10.1038/nature01214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Zhang F, Hancock CN, Wessler SR. Transposition of the rice miniature inverted repeat transposable element mPing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(26):10962–10967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702080104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casacuberta JM, Santiago N. Plant LTR-retrotransposons and MITEs: control of transposition and impact on the evolution of plant genes and genomes. Gene. 2003;311:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00557-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Nagel DH, Feschotte C, Hancock CN, Wessler SR. Tuned for transposition: molecular determinants underlying the hyperactivity of a Stowaway MITE. Science. 2009;325(5946):1391–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1175688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana D, Boogaart T, O'Neill CM, Hynes L, Bent E, Macpherson L, Park JY, Lim YP, Bancroft I. Conservation of the microstructure of genome segments in Brassica napus and its diploid relatives. Plant J. 2004;40(5):725–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truco MJ, Hu J, Sadowski J, Quiros CF. Inter- and intra-genomic homology of the Brassica genomes: Implications for their origin and evolution. Theor Appl Genet. 1996;93(8):1225–1233. doi: 10.1007/BF00223454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarilar V, Marmagne A, Brabant P, Joets J, Alix K. BraSto, a Stowaway MITE from Brassica: recently active copies preferentially accumulate in the gene space. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;77(1–2):59–75. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9794-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontdevila A. Hybrid genome evolution by transposition. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110(1–4):49–55. doi: 10.1159/000084937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Hawkins JS, Grover CE, Wendel JF. The history and disposition of transposable elements in polyploid Gossypium. National Research Council Canada = Genome Conseil national de recherches Canada. 2010;53(8):599–607. doi: 10.1139/G10-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago N, Herraiz C, Goni JR, Messeguer X, Casacuberta JM. Genome-wide analysis of the Emigrant family of MITEs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(12):2285–2293. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhou F, Li G, Xu Y. MUST: a system for identification of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements and applications to Anabaena variabilis and Haloquadratum walsbyi. Gene. 2009;436(1–2):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14(6):1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayele M, Haas BJ, Kumar N, Wu H, Xiao Y, Van Aken S, Utterback TR, Wortman JR, White OR, Town CD. Whole genome shotgun sequencing of Brassica oleracea and its application to gene discovery and annotation in Arabidopsis. Genome Res. 2005;15(4):487–495. doi: 10.1101/gr.3176505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee SC, Lim MH, Kim JA, Lee SI, Kim JS, Jin M, Kwon SJ, Mun JH, Kim YK, Kim HU. Transcriptome analysis in Brassica rapa under the abiotic stresses using Brassica 24 K oligo microarray. Mol Cells. 2008;26(6):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J, Doyle J. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf F. NTSYS-pc, version 2.10 z. Setauket, New York: Exeter Software; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Physical position of the 697 members in the B. rapa genome.

List of Primers used for MITE insertion polymorphism analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis of MIPs. Dendrogram based on Jaccard’s similarity coefficient of 50 MIPs among eight genotypes constructed using the UPGMA method.

MIP survey of 94 B. oleracea F2 plants from a cross between parental lines C1234 (P1) and C1184 (P2). The primer MIP-M1-19 was used and a ratio of 22:50:21 was observed for genotypes P1: P1/P2 : P2.