Abstract

Background

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae is the causative agent of porcine enzootic pneumonia (EP), a mild, chronic pneumonia of swine. Despite presenting with low direct mortality, EP is responsible for major economic losses in the pig industry. To identify the virulence-associated determinants of M. hyopneumoniae, we determined the whole genome sequence of M. hyopneumoniae strain 168 and its attenuated high-passage strain 168-L and carried out comparative genomic analyses.

Results

We performed the first comprehensive analysis of M. hyopneumoniae strain 168 and its attenuated strain and made a preliminary survey of coding sequences (CDSs) that may be related to virulence. The 168-L genome has a highly similar gene content and order to that of 168, but is 4,483 bp smaller because there are 60 insertions and 43 deletions in 168-L. Besides these indels, 227 single nucleotide variations (SNVs) were identified. We further investigated the variants that affected CDSs, and compared them to reported virulence determinants. Notably, almost all of the reported virulence determinants are included in these variants affected CDSs. In addition to variations previously described in mycoplasma adhesins (P97, P102, P146, P159, P216, and LppT), cell envelope proteins (P95), cell surface antigens (P36), secreted proteins and chaperone protein (DnaK), mutations in genes related to metabolism and growth may also contribute to the attenuated virulence in 168-L. Furthermore, many mutations were located in the previously described repeat motif, which may be of primary importance for virulence.

Conclusions

We studied the virulence attenuation mechanism of M. hyopneumoniae by comparative genomic analysis of virulent strain 168 and its attenuated high-passage strain 168-L. Our findings provide a preliminary survey of CDSs that may be related to virulence. While these include reported virulence-related genes, other novel virulence determinants were also detected. This new information will form the foundation of future investigations into the pathogenesis of M. hyopneumoniae and facilitate the design of new vaccines.

Keywords: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, Genetic variation, Virulence attenuation, Sequence analysis, Repetitive sequences, Virulence factors

Background

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae causes porcine enzootic pneumonia, which is a mild, chronic pneumonia of swine [1]. This highly infectious organism has a worldwide distribution. The primary mycoplasmal infection often becomes complicated by secondary bacterial and viral infections [2], resulting in more severe lung lesions and production losses. Relative control has been achieved through active vaccination programs, but porcine enzootic pneumonia continues to be a major economic problem in the swine industry. While progress has been made in understanding the molecular basis of some Mycoplasma diseases [3], advances in M. hyopneumoniae research have been hampered by its fastidious growth condition and the lack of genetic tools and transformation protocols. To date, few virulence determinants or virulence-associated determinants have been identified. Attachment to the respiratory epithelium is a prerequisite for host colonization and is mediated by the membrane protein P97 [4]. This protein is located on the outer membrane surface, and its role in adherence has been firmly established. The general region of P97 that mediates adherence to swine cilia is thought to be the R1 region, near the C-terminus of the protein [5]. To bind cilia, a minimum of eight tandem copies of the pentapeptide sequence (AAKPV/E) in R1 are required [5]. Although the function of R2 in vivo is unknown, both it and R1 are required to bind heparin [6]. The P97 genes of M. hyopneumoniae strains 7448, 232, and J code for proteins with 10, 15, and 9 of the previously described R1 repeating units (AAKPV/E), respectively; all three strains had more than the minimum number of tandem copies (8 tandem copies) required for cilium binding [7]. Moreover, monoclonal antibodies F1B6 and F2G5, which both react predominantly with P97 [4,5], only partially block adherence of M. hyopneumoniae to receptors on epithelial cell cilia [8]. These observations indicate that molecules other than P97 play a role in facilitating adherence of M. hyopneumoniae to swine cilia. Comparative transcriptomic and proteomic studies are also performed to study transcriptional changes that occur during disease and investigate differentially expressed proteins in pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains [9-11]. Several M. hyopneumoniae proteins, including immunodominant proteins (P36 [12], P46 [13], and P65 [14]), adhesin-related proteins (P102 [15], P146 [16], P159 [17], P216 [18], and LppT [16]), and a 54-kDa cytotoxic factor [19], have been characterized; however, the biological functions of these proteins in pathogenesis are not well understood.

Comparative genomic analysis has previously revealed mechanisms of M. hyopneumoniae pathogenicity [7] and predicted unidentified virulence factors, including genes involved in secretion and/or traffic between host and pathogen cells, or with evasion and/or modulation of the host immune system [20,21]. In 2005, Vasconcelos et al. sequenced a pathogenic and a non-pathogenic strain of M. hyopneumoniae and performed a comparative genomics approach to identify putative virulence genes [7]. They identified various CDSs that could be considered candidate virulence genes, including cilium adhesin homologs, lipoproteins, and other components which might contribute to virulence [7]. However, comparative genomic analysis of a virulent M. hyopneumoniae strain versus its attenuated strain is lacking.

The need to control the spread of M. hyopneumoniae prompted the development of live attenuated vaccine strains. M. hyopneumoniae strain 168-L has been extensively used as vaccine against M. hyopneumoniae in China [22,23]. This attenuated vaccine strain is derived from the virulent parent strain 168. Strain 168 was originally isolated in 1974, from an Er-hua-nian pig (a Chinese local breed very sensitive to M. hyopneumoniae) with typical clinical and pathogenic characteristics of mycoplasmal pneumonia of swine (MPS) [24]. This field strain was gradually attenuated by more than 300 continuous passages through KM2 cell-free medium (a modified Friis medium) and the 380th passage was named strain 168-L. Currently, the genetic basis for the attenuation of virulence in 168-L is poorly understood.

To gain new insight into the components that contribute to virulence and the mechanisms by which M. hyopneumoniae causes disease, we sequenced the genomes of strains 168 and 168-L. This allowed us to perform the first comprehensive analysis of virulent and attenuated strains, and identify CDSs that may be related to virulence. We further investigated these putative virulence related CDSs and compared them with reported virulence determinants. Notably, almost all reported virulence determinants were found in putative virulence related CDSs. Besides the reported virulence determinants, other candidate virulence genes were also identified. The study of these candidate virulence genes and their corresponding products will be important to better comprehend the pathogenesis of M. hyopneumoniae.

Results and discussion

Genomic features of M. hyopneumoniae 168-L and its global comparison with pathogenic strain 168

The complete genome of M. hyopneumoniae 168-L consists of a 921,093 bp (GC content 28.46%) single circular chromosome (GenBank accession number CP003131). A total of 689 protein-encoding genes were predicted. The average protein size is 378 amino acids and the mean coding percentage is 84.8%. Approximately 51% of genes were assigned to specific functional clusters of orthologous groups (COGs), and 28% were assigned an enzyme classification (EC) number (Figure 1). Comparison with the M. hyopneumoniae 168 genome (GenBank accession CP002274) revealed a highly conserved gene content and order between the two strains. The 168-L genome is 4,483 bp smaller than that of 168 (925,576 bp), because there are 60 insertions and 43 deletions (indels; insertions and deletions of any size) in 168-L relative to 168 (see Additional file 1: Table S1; Additional file 2: Table S2; Additional file 3: Table S3). Among these, 33 indels are located in predicted CDSs, and 70 are in noncoding regions. Besides these indels, 227 single nucleotide variations (SNVs) were identified between 168 and 168-L (Additional file 4: Table S4). While 31 SNVs were mapped to intergenic regions, 196 were in coding regions, inducing amino acid substitutions, frame shifts, and translational stops.

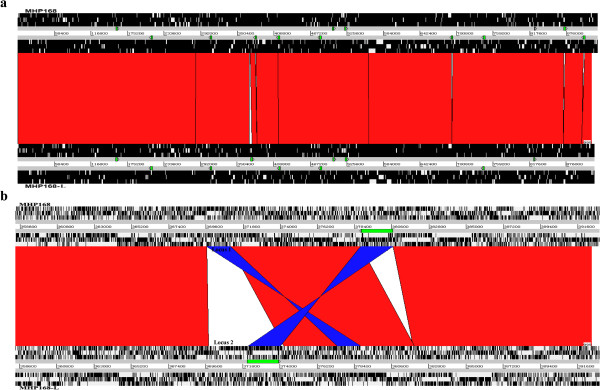

Figure 1.

Genome architecture. The dnaA gene is at position zero. Moving inside, the first circle shows the genome length (units in M. hyopneumoniae); the second and the third circles show the locations of the predicted CDSs on the plus and minus strands, respectively, which were color-coded by COG categories (the color codes for the functional assignments are shown in the key); the fourth circle shows tRNAs (purple) and rRNAs (red); the fifth circle shows the centered GC (G+C) content of each CDS (blue: above mean and cyan: below mean); and the sixth circle shows the GC (G+C) skew plot (red: above zero and pink: below zero). Circles 7–10 show comparative amino acids analysis of 168 with amino acids identities color-coded according to the similarity shown in the key to strains 168-L (seventh circle), 232 (eight circle), J (ninth circle), 7448 (tenth circle).

ISMHp1-Related genetic variations between 168 and 168-L

The difference between the genome sizes of strains 168 and 168-L is mainly due to differences in the duplication of Insertion Sequence (IS) elements. IS elements are distributed stochastically across the entire genome of both strains. The 168-L genome contains nine complete and one disrupted IS elements, which is almost identical to that of 168 except for slight differences in ISMHp1. There are nine complete copies of ISMHp1 in 168-L, but 12 copies in 168. The difference in ISMHp1 copy number between 168 and 168-L is due to three complete ISMHp1 deletions (located 690 kb, 870 kb, and 900 kb from oriC) and one complete ISMHp1 inversion, which was originally located at 378 kb from oriC, but was inverted in 168-L (1656 bp, located 372 kb from oriC) (Figure 2a).

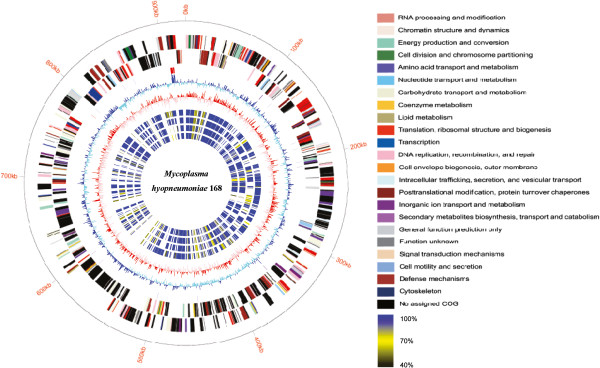

Figure 2.

Alignment of the whole genomes and inverted regions. (a) Alignment of the M. hyopneumoniae 168 and 168-L genomes. (b) Alignment of the inverted regions of 168 relative to 168-L. The gray bars represent the forward and reverse strands. Green triangles represent ISMHP1 elements. DNA BLASTN alignments (BLASTN matches) between the two sequences are indicated by a red (same strand) or blue (opposite strand) line.

Other than the IS elements, notable large-scale genomic differences were also indicated. Compared to strain 168, a genomic deletion of approximately 1.36 kb (locus 1: between MHP168L_311 and MHP168L_729) was identified, which had been substituted with an approximately 2.32 kb novel insertion sequence (locus 2) that was joined to a complete ISMHp1 element in 168-L (Figure 2b). This 168-L-related insertion fragment was also observed in strains 7448 and 232.

Molecular analysis of integrative conjugative element (ICE)

The integrative conjugative element (ICE) is a mobile DNA that is probably involved in genomic recombination events and in pathogenicity. The ICEH elements are more divergent than the typical similarity of other chromosomal locus in M. hyopneunomiae[25], suggesting an accelerated evolution of these constins [26]. During a survey of specific sequences, a specific 26.9-kb region with similarity to the integrative conjugal element of M. fermentans (ICEF) [27] was found in strain 168, which was designated ICEH (for integrative conjugal element of M. hyopneumoniae). Unlike ICEH in strains 7448 and 232, which consist of nineteen and twenty two CDSs, respectively, the ICEH168 consist of 20 CDSs (Additional file 5: Table S5). The organization of these elements is very similar. Some CDSs present similarity to tra genes, which are usually associated with the bacteria conjugative plasmids such as traK, traI, traE[26]. The ICEH168 has three tra genes, with one traG and two copies of the traE gene. Besides, a CDS encoding for a single strand binding protein (SSB) that is essential for the transfer process is also observed.

The ICE analysis of three M. hyopneumoniae genomes (7448, J and 232) carried out previously, revealed that the ICEH is present in the two pathogenic strains (7448 and 232) but is absent from the non-pathogenic one (J strain) [26]. Interest has therefore shifted to questions of whether the ICEH is present in the attenuated vaccine strain 168-L. Interestingly, the ICEH was also observed in strain 168-L. Moreover, the ICEH168 and ICEH168-L are almost the same, except for a missense mutation (G192E) identified in ICEH-ORF3 (MHP168_235). Our analyses indicate that the ICEH may not only present in pathogenic strains of M. hyopneumoniae.

Mutations affecting epithelium adhesion

In our previous study, the ability of adherence and damage to the cilia between strains 168 and 168-L were compared by using scanning electron microscopy. The results showed that the pathogenic strain 168 adheres to cilia inducing tangling, clumping, and longitudinal splitting of cilia, while the strain 168-L does not cause ciliary damage comparing to control group [28]. The adherence of M. hyopneumoniae to porcine ciliated respiratory cells is essential for the organism to colonize the respiratory epithelium and cause pneumonia [4]. The adherence process is mainly mediated by receptor-ligand interactions, and the M. hyopneumoniae proteins possibly involved in these interactions are obvious candidates as virulence factors [8,29-31]. We investigated the genetic variation between strains 168 and 168-L (Table 1; Additional file 6: Table S6), and compared mutations affecting CDSs corresponding to previously described mycoplasma adhesins (P97, P102, P146, P159, P216, MgPa, LppS, and LppT) [7]. Notably, almost all the reported mycoplasma adhesins are included in the CDSs affected by mutations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Complete list of "168-L-specific" genetic variations in CDSs

| 168-L gene | 168-L gene product | Variation | 168 Locus | Effect on 168-L coding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHP168L_010 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_010 |

L368A substitution |

| MHP168L_014 |

Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase |

Deletion+SNV |

MHP168_014 |

N-terminal deletion+SNV |

| MHP168L_020 |

ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

Deletion |

MHP168_020 |

264-aa deletion |

| MHP168L_022 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_022 |

S22S substitution |

| MHP168L_030 |

Topoisomerase IV subunit A |

SNV |

MHP168_030 |

K140E substitution |

| MHP168L_033 |

Predicted protein |

Deletion |

MHP168_033 |

N-terminal deletion |

| MHP168L_035 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_035 |

K177R,A221T substitution |

| MHP168L_058 |

Glycyl-tRNA synthetase |

SNV |

MHP168_058 |

P226P substitution |

| MHP168L_064 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_064 |

Y552H substitution |

| MHP168L_065 |

Predicted protein |

Deletion |

MHP168_065 |

Frameshift out 20aa |

| MHP168L_066 |

hypothetical protein |

Insertion+SNV |

MHP168_066 |

Frameshift out 42aa; F324S substitution |

| MHP168L_069 |

Chaperone protein dnaK |

SNV |

MHP168_069 |

P407P substitution |

| MHP168L_084 |

Amino acid permease |

SNV |

MHP168_084 |

R13K,T396A substitution |

| MHP168L_085 |

NADH oxidase |

Insertion+SNV |

MHP168_085 |

"TG" insertion; stop; 5aa truncation; E395G substitution |

| MHP168L_086 |

Thymidine phosphorylase |

SNV |

MHP168_086 |

V15F substitution |

| MHP168L_103 |

Outer membrane protein-P95 |

SNV |

MHP168_103 |

Stop;149-aa truncation |

| MHP168L_105 |

ATP-dependent protease binding protein |

SNV |

MHP168_105 |

I159I substitution |

| MHP168L_110 |

Protein p97, cilium adhesin |

SNV |

MHP168_110 |

SNV in repeat region |

| MHP168L_114 |

50S ribosomal protein L2 |

SNV |

MHP168_114 |

A2A substitution |

| MHP168L_127 |

50S ribosomal protein L15 |

SNV |

MHP168_127 |

E95K substitution |

| MHP168L_142 |

Phosphopentomutase |

SNV |

MHP168_142 |

N8I substitution |

| MHP168L_152 |

ribulose-phosphate 3-epimerase |

Deletion+SNV |

MHP168_152 |

I211F substitution |

| MHP168L_167 |

L-lactate dehydrogenase |

SNV |

MHP168_167 |

N204D substitution |

| MHP168L_168 |

Hexosephosphate transport protein |

SNV |

MHP168_168 |

Q122S substitution |

| MHP168L_182 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Deletion |

MHP168_182 |

Frameshift;105-aa truncation |

| MHP168L_186 |

Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1-alpha subunit |

SNV |

MHP168_186 |

S194G substitution |

| MHP168L_187 |

Adenine phosphoribosyltransferase |

SNV |

MHP168_188 |

534-aa N-terminal extension |

| MHP168L_198 |

Protein P102 |

SNV |

MHP168_198 |

L677L substitution |

| MHP168L_209 |

ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

SNV |

MHP168_209 |

K258E substitution |

| MHP168L_212 |

Oligopeptide transport system permease protein |

SNV |

MHP168_212 |

P203S substitution |

| MHP168L_235 |

Putative ICEF Integrative Conjugal Element-II |

SNV |

MHP168_235 |

G192E substitution |

| MHP168L_243 |

Serine hydroxymethyltransferase |

Insertion |

MHP168_243 |

No change |

| MHP168L_264 |

ISMHp1 transposase |

SNV |

MHP168_264 |

S232P,C229R substitution |

| MHP168L_275 |

lipoate-protein ligase A |

SNV |

MHP168_275 |

A179T substitution |

| MHP168L_284 |

Cobalt import ATP-binding protein cbiO 1 |

SNV |

MHP168_284 |

K64E substitution |

| MHP168L_289 |

Cation-transporting P-type ATPase |

SNV |

MHP168_289 |

E100D substitution |

| MHP168L_308 |

putative ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

SNV |

MHP168_308 |

T708A,M700L substitution |

| MHP168L_311 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_311 |

D266E substitution |

| MHP168L_312 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Insertion+SNV |

MHP168_312 |

Insertion;R49R,I247L substitution |

| MHP168L_314 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Insertion+deletion |

MHP168_314 |

Stop;14-aa truncation |

| MHP168L_322 |

hypothetical protein |

Insertion |

MHP168_322 |

Frameshift;5-aa truncation |

| MHP168L_345 |

Predicted protein |

Deletion |

MHP168_345 |

Frameshift;53-aa truncation |

| MHP168L_355 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Insertion |

MHP168_355 |

21-aa N-terminal deletion |

| MHP168L_361 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_361 |

L265L substitution |

| MHP168L_377 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_377 |

E407K substitution |

| MHP168L_378 |

P60-like lipoprotein |

SNV |

MHP168_378 |

S143N substitution |

| MHP168L_379 |

HIT-like protein |

SNV |

MHP168_379 |

D58N substitution |

| MHP168L_381 |

hypothetical protein |

Insertion |

MHP168_381 |

Frameshift |

| MHP168L_386 |

P37-like ABC transporter substrate-binding lipoprotein |

Insertion |

MHP168_386 |

Frameshift out 84aa |

| MHP168L_389 |

Putative membrane lipoprotein |

SNV |

MHP168_389 |

A265S substitution |

| MHP168L_392 |

lipoprotein |

SNV |

MHP168_392 |

T6M substitution |

| MHP168L_394 |

ABC transporter permease protein |

SNV |

MHP168_394 |

A492G substitution |

| MHP168L_400 |

Ribonuclease III |

SNV |

MHP168_400 |

V58I substitution |

| MHP168L_401 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Deletion |

MHP168_401 |

Frameshift out 133aa |

| MHP168L_409 |

Putative type III restriction-modification system: methylase |

Deletion |

MHP168_409 |

Frameshift out 171aa |

| MHP168L_412 |

ISMHp1 transposase |

SNV |

MHP168_412 |

G50V substitution |

| MHP168L_413 |

ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

SNV |

MHP168_413 |

D118Y substitution |

| MHP168L_423 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_423 |

Y18S substitution |

| MHP168L_424 |

Lppt protein |

SNV |

MHP168_424 |

L814F substitution |

| MHP168L_434 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_434 |

W107C substitution |

| MHP168L_444 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_444 |

V123A substitution |

| MHP168L_445 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Deletion |

MHP168_445 |

3-aa deletion in repeat region |

| MHP168L_454 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Insertion+SNV |

MHP168_454 |

L423I substitution |

| MHP168L_455 |

Predicted protein |

Deletion+SNV |

MHP168_455 |

59-aa extension;P51P substitution |

| MHP168L_456 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_456 |

substitution |

| MHP168L_457 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Insertion+deletion+SNV |

MHP168_457 |

Frameshift;substitution |

| MHP168L_462 |

ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

SNV |

MHP168_462 |

V219L substitution |

| MHP168L_463 |

ABC transporter permease protein |

SNV |

MHP168_463 |

Amino acid substitution |

| MHP168L_473 |

hypothetical protein |

Insertion |

MHP168_473 |

Frameshift out 84aa |

| MHP168L_482 |

Phosphoenolpyruvate protein phosphotransferase |

SNV |

MHP168_482 |

E562G substitution |

| MHP168L_490 |

hypothetical protein |

Insertion |

MHP168_490 |

Stop;114-aa truncation |

| MHP168L_498 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_498 |

D137E substitution |

| MHP168L_503 |

P216 surface protein |

Insertion |

MHP168_503 |

Q repeat insertion |

| MHP168L_504 |

P159 membrane protein |

SNV |

MHP168_504 |

G403D,L375S, G240A substitution |

| MHP168L_505 |

YX1 |

SNV |

MHP168_505 |

V175I substitution |

| MHP168L_506 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_506 |

N16N substitution |

| MHP168L_507 |

asparagine synthetase A |

SNV |

MHP168_507 |

I85M substitution |

| MHP168L_510 |

Oligopeptide transport system permease protein |

SNV |

MHP168_510 |

S19S substitution |

| MHP168L_523 |

Xylose ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

SNV |

MHP168_523 |

S8S substitution |

| MHP168L_531 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Deletion+SNV |

MHP168_531 |

Amino acid substitution |

| MHP168L_541 |

Predicted protein |

SNV |

MHP168_541 |

L50L substitution |

| MHP168L_557 |

Potassium uptake protein |

SNV |

MHP168_557 |

D69Y substitution |

| MHP168L_558 |

Potassium uptake protein |

SNV |

MHP168_558 |

H425Y,N477D substitution |

| MHP168L_559 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_559 |

D1236G substitution |

| MHP168L_567 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_567 |

D68N substitution |

| MHP168L_571 |

hypothetical protein |

Insertion+deletion+SNV |

MHP168_571 |

Frameshift;amino acid substitution |

| MHP168L_573 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Deletion+SNV |

MHP168_573 |

Amino acid substitution;N-terminal extension |

| MHP168L_576 |

ISMHp1 transposase |

SNV |

MHP168_576 |

Amino acid substitution |

| MHP168L_589 |

Membrane nuclease, lipoprotein |

SNV |

MHP168_589 |

S98S substitution |

| MHP168L_596 |

Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

SNV |

MHP168_596 |

L155V substitution |

| MHP168L_600 |

ABC transporter ATP binding protein |

SNV |

MHP168_600 |

P1014L,P1037L substitution |

| MHP168L_606 |

hypothetical protein |

Deletion+SNV |

|

Frameshift;amino acid substitution |

| MHP168L_614 |

ABC transporter xylose-binding lipoprotein |

SNV |

MHP168_614 |

I51V substitution |

| MHP168L_621 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_621 |

G87G substitution |

| MHP168L_631 |

ABC transporter ATP-binding-Pr1 |

SNV |

MHP168_631 |

R60W substitution |

| MHP168L_638 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

Insertion+SNV |

MHP168_638 |

K insertion in K repeat region;K7K substitution |

| MHP168L_639 |

5'-nucleotidase precursor |

SNV |

MHP168_639 |

E411K substitution |

| MHP168L_666 |

Ribosomal RNA small subunit methyltransferase G |

Deletion |

MHP168_666 |

Frameshift out 12aa |

| MHP168L_668 |

Prolipoprotein p65 |

SNV |

MHP168_668 |

T138A substitution |

| MHP168L_671 |

XAA-PRO aminopeptidase |

SNV |

MHP168_671 |

G321G substitution |

| MHP168L_672 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_672 |

E104E substitution |

| MHP168L_673 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_673 |

I52K,E127K substitution |

| MHP168L_675 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_675 |

Y175D substitution |

| MHP168L_676 |

P146 adhesin like-protein, p97 paralog |

Insertion+SNV |

MHP168_676 |

Q insertion in PQ repeat region;S404S,W404R substitution |

| MHP168L_688 |

Putative uncharacterized protein |

SNV |

MHP168_688 |

K48N substitution |

| MHP168L_698 |

hypothetical protein |

SNV |

MHP168_698 |

R126G,V159G substitution |

| MHP168L_707 |

hypothetical protein |

Insertion |

MHP168_707 |

"F" insertion |

| MHP168L_747 |

hypothetical protein |

Insertion+deletion+SNV |

MHP168_091 |

N repeat insertion;39-aa N-terminal extension;SNV |

| MHP168L_748 |

Protein P102 |

Deletion+SNV |

MHP168_108 |

Stop;782-aa truncation;SNV |

| MHP168L_749 |

Putative type III restriction-modification system: methylase |

Deletion |

MHP168_730 |

N-terminal deletion |

| MHP168L_750 |

hypothetical protein |

Deletion |

MHP168_435 |

Frameshift |

| MHP168L_r002 |

16S ribosomal RNA |

SNV |

MHP168_r002 |

Amino acid substitution |

| MHP168L_t027 | tRNA-Ser | SNV | MHP168_t027 | Amino acid substitution |

In 168-L, three transversions were identified in the R1 region, near the C-terminus, of P97 (MHP168_110/MHP168L_110), which encodes cilium adhesin. In M. hyopneumoniae, attachment to the respiratory epithelium is mainly mediated by the membrane protein P97 [4]. This protein is located on the outer membrane surface, and its role in adherence has been firmly established. To bind cilia, a minimum of eight tandem copies of the pentapeptide sequence (AAKPV/E) in R1 are required [5]. Notably, all three transversion mutations were located in the tandem repeat unit (AAKPV/E), causing an E863V substitution. Significant alteration in this critical repeat unit might partly affect the adhesion reaction in 168-L.

Previous studies have demonstrated that P102 binds fibronectin and contributes to the recruitment of plasmin(ogen) to the M. hyopneumoniae cell surface [15]. P102 is commonly linked to P97 cilium adhesin, forming a two-gene operon [32]. Both P97 and P102 have several paralogs within the M. hyopneumoniae genome. However, the paralogs have only part of the complete sequence. Interestingly, P102, the companion gene in this operon, was truncated at 564 bp by a single base insertion in strain 168. Another intact copy of P102 (99% identity) was found 85 kb from this operon. Conversely, in strain 168-L, the original truncated P102 was reverted to the intact one, while another intact copy of P102, 85 kb away, was truncated.

The P146 adhesin-like protein of M. hyopneumoniae shows strong similarity to the LppS lipoprotein of Mycoplasma conjunctivae, which is involved in in vitro adhesion [16]. In addition, the N-terminus region of P146 also shows strong similarity to the P97 adhesin, and has a strongly hydrophobic region (amino acids 7–29), indicating a transmembrane region, and suggesting that the protein is expressed on the surface of M. hyopneumoniae cells [33]. Compared with its counterpart MHP168_676 in 168, MHP168L_676 from 168-L has an in-frame insertion of one amino acid (Q) at the N-terminus of P146. The enormous intra-specific diversity shown for the P146 encoding gene is at least partly because of differences between several repeat regions present in the gene, most notably a polyserine chain of variable length, and a [Q]n[(P/S)Q]m repeat region [34]. Interestingly, this one in-frame insertion (Q) was located in the [Q]n[(P/S)Q]m repeat region. Polyserine chains often function as a spacer region in proteins involved in complex carbohydrate degradation [35], while sequences rich in both proline and glutamine are not uncommon and can form a conformation known as a polyproline II helix [36,37]. Such proline-rich sequences are often involved in binding processes and are highly immunogenic [37]. However, because the function of the P146 protein remains unknown, correlations with virulence or adhesion are speculative and need further investigation.

P159 is a proteolytically processed surface adhesin of M. hyopneumoniae[17]. Three proteins with apparent molecular masses of 27 (P27), 52 (P52), and 110 (P110) kDa were identified through proteomic analysis of M. hyopneumoniae lysates [17], with each representing a different region spanning P159. These cleavage fragments are located on the cell surface and present at all growth stages. In 168-L, MHP168L_504 (P159) has a missense mutation resulting in a G240A replacement in the (S)(S)G(G)S repeat region of P159. Although this (S)(S)G(G)S repeat region has been reported, its biological function is unknown.

P216 (MHP168L_503/MHP168_503) is a proteolytically processed cilium and heparin binding protein of M. hyopneumoniae[18]. This surface protein is post-translationally processed to generate N-terminal P120 and C-terminal P85 fragments, both of which can bind cilia [18]. The 168-L P216 gene has an in-frame four amino acid deletion in a poly Q motif near the C-terminus. Previous studies have suggested that poly Q and KEKE motifs may play a role in maintaining P85 on the cell surface [18,34]. Collectively, the deletion mutations affecting P216 may affect its cilium adhesion and may be associated with virulence attenuation in 168-L.

The MHP168L_424 gene and its gene product LppT were analyzed in detail because they showed approximately 22% identity to the LppT protein from M. conjunctivae. LppT is the second gene in a two gene operon with LppS, which was reported to be an adhesin in M. conjunctivae[16]. The LppT gene lacked a promoter and is likely to be co-transcribed with LppS, thus suggesting a functional relationship between LppS and LppT [16]. In M. hyopneumoniae, LppT encoded a protein of 954 aa with a calculated molecular mass 108 kDa. The gene product encoded by LppT is also a membrane protein, with a signal sequence of 34 aa at the amino-terminal end and a transmembrane structure. Notably, one of the amino acid substitutions in 168-L occurs near the C-terminus of LppT, resulting in a L814F replacement.

Mutations altering the cell envelope and genes encoding secreted proteins

Cell envelope proteins and secreted proteins are involved in virulence, host cell interaction, and immune responses [14,38,39]. Outer membrane protein-P95 is a cell envelope protein in M. hyopneumoniae. In 168-L, MHP168L_103 (P95) is truncated by a nonsense mutation compared to 168, resulting in an E965* termination near the C-terminus of P95. Significant alteration in this outer membrane protein could conceivably cause a truncation in coding region, and in turn alter the function of P95 outer membrane protein.

M. hyopneumoniae contains an abbreviated membrane protein secretory system [1]. The pathway consists of secA (MHP168L_088), secY (MHP168L_128), secD (MHP168L_259), prsA (MHP168L_664), dnaK (MHP168L_069), trigger factor (MHP168L_154), and lepA (MHP168L_076). It has recently been demonstrated that some pathogenic bacteria use a type IV secretion system, composed of subunits related to the conjugation machinery, to deliver effector molecules to host cells [40], and that this system may be involved in pathogenesis [41]. We found no pathogenic mutations in the protein secretory system, except a synonymous substitution (P407P) in MHP168L_069, which encodes chaperone protein DnaK.

Mutations affecting antigens

Studies on the antigenic properties of M. hyopneumoniae revealed several immunodominant proteins, including the P36 cytosolic protein [12,42], the P46, P65, and P74 membranous proteins [43-46], the elongation factor Tu [47], the chaperone protein DnaK[47], the pyruvate dehydrogenase E1-beta subunit [47], and the P97 adhesin [4]. The functions of these proteins have not been well elucidated, but specific reactants may eventually be useful tools to diagnose M. hyopneumoniae[48].

The cytosolic P36 protein is a lactate dehydrogenase [49] that induced an early immune response in pigs that are experimentally and naturally infected by M. hyopneumoniae[50]. Comparative studies with other Mycoplasmas commonly found in pigs demonstrated that the P36 proteins carry highly conserved species-specific antigenic determinants for M. hyopneumoniae[42]. Hyperimmune sera produced against recombinant P36 protein showed no reactivity against other porcine Mycoplasmas, including M. flocculare, M. hyorhinis, and Acholeplasma laidlawii[12]. Notably, one of the observed amino acid substitutions in 168-L occurs near the C-terminus of P36 (MHP168L_167), resulting in a N204D replacement.

P65 is an immunodominant surface lipoprotein of M. hyopneumoniae that is specifically recognized during disease [14]. Analysis of the translated amino acid sequence of the gene encoding p65 revealed similarity to the GDSL family of lipolytic enzymes [14]. The monospecific antibodies against heat shock protein-like P42 antigen, part of P65, can block the growth of M. hyopneumoniae[51]. In 168-L, MHP168L_668 (P65) has a missense mutation resulting in a T138A replacement.

Mutations affecting transport proteins

As Mycoplasmas are dependent on the exogenous supply of many nutrients, it has been predicted that they may need many transport systems [3]. Motif analysis revealed a family of proteins with a phosphotransferase (PTS) motif. The open reading frames (ORFs) included sgaA (MHP168L_422), sgaB (MHP168L_421), sgaT (MHP168L_563), mtlF (MHP168L_739), mtlA (MHP168L_561), nagE (MHP168L_582), and licA (MHP168L_041) [7]. However, no mutations were identified in this PTS transporter family. There are approximately 30 genes with ABC transporter family signatures in the genome of M. hyopneumoniae 168-L (Additional file 7: Table S7), and five missense mutations and one synonymous substitution were identified in this group. These included a cobalt import ATP-binding protein (MHP168L_284, K64E), an ABC transporter permease protein (MHP168L_394, A492G), a xylose ABC transporter ATP-binding protein (MHP168L_523, S8S), and three ABC transporter ATP-binding proteins (MHP168L_413, D118Y; MHP168L_462, V219L; MHP168L_631, R60W). Interestingly, the expression of MHP168L_394 and MHP168L_413 was reported to be up-regulated in vivo during disease relative to in vitro-grown [11]. The variability between strains 168 and 168-L in multi-transport proteins indicates that they may affect growth and survival in different hosts or host tissues.

Mutations affecting genes directly related to metabolism and in vivo growth

M. hyopneumoniae strain 168 encodes 695 genes, approximately one quarter of which are involved in metabolism and in vivo growth. Of particular interest were the mutations observed in the genes involved in various metabolic pathways (Figure 3), including glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (MHP168_167, MHP168_186), purine metabolism (MHP168_289, MHP168_639), pyrimidine metabolism (MHP168_086), glycerophospholipid metabolism (MHP168_596), oxidative phosphorylation (MHP168_085), aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis (MHP168_058), and the pentose phosphate pathway (MHP168_142, MHP168_152). An in-frame insertion of two amino acids (TG), a missense mutation (E393G) and a nonsense mutation (N456*) were identified in 168-L near the C-terminus of MHP168L_085, which encodes a NADH oxidase involved in oxidative phosphorylation. Mycoplasma genomes are deficient in genes coding for components of intermediary and energy metabolism [3]. Thus, Mycoplasmas depend mostly on glycolysis to synthesize ATP [3]. In the glycolysis pathway, missense mutations in both L-lactate and pyruvate dehydrogenase were observed, resulting in N204D and S194G replacements, respectively. Iron deprivation, is a prominent feature of the host innate immune response, and most certainly impacts growth of Mycoplasmas in vivo[52]. Through transcriptome analysis, MHP168_639 was identified to be down-regulated during iron limiting conditions [52]. This suggests that MHP168_639 may play a role in M. hyopneumoniae’s response to iron stress. In 168-L, MHP168L_639 has a missense mutation resulting in an E411K replacement. Mutations in these metabolism-related genes accumulated over 300 in vitro passages likely affect growth and survival within host cells.

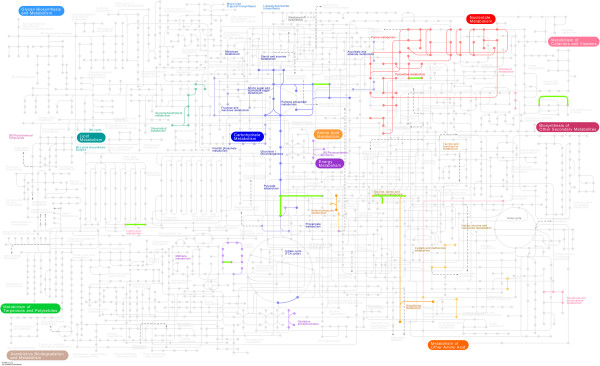

Figure 3.

Metabolic potential. The metabolic pathways of M. hyopneumoniae strains 168 and 168-L were mapped and analyzed using KEGG Pathway Database. Those pathways, containing mutations affected metabolic-related genes, are shown in green.

In addition, approximately 41% of mutations affected genes coding for hypothetical proteins. Despite the lack of functional annotations for these genes, their disruption in 168-L makes them obvious targets for investigation as potential virulence factors. Further molecular genetics and in vivo studies are required to confirm and assess the relative importance of these genes in the attenuation of virulence in 168-L.

Conclusions

We successfully used a combination of sequencing genomics and comparative genomics strategies to provide a comprehensive analysis of virulent and attenuated M. hyopneumoniae strains to identify determinants involved in pathogenesis. The genome of the attenuated high-passage derivative strain 168-L was sequenced and compared to virulent strain 168, revealing mutations in numerous CDSs. These mutations affected CDSs are likely to be associated with virulence. We then compared these putative virulence factor CDSs to reported virulence determinants. Notably, almost all of the reported M. hyopneumoniae virulence determinants were included in the list of putative virulence factor CDSs. Variations in the previously described mycoplasma adhesins (P97, P102, P146, P159, P216 and LppT), cell envelope proteins (P95), cell surface antigens (P36), secreted proteins, chaperone protein (DnaK), and genes directly related to metabolism and in vivo growth may contribute to loss of virulence in 168-L. We then proceeded to characterize the alterations in gene functions caused by mutations at the protein level, and compared those mutations with previously described repeat motifs that may be of primary importance for virulence [34]. Interestingly, we found that many mutations were located in the virulence associated motifs of the various proteins. To bind cilia, a minimum of eight tandem copies of the pentapeptide sequence (AAKPV/E) in the R1 region of P97 are required [5]. We identified three mutations in the tandem repeat unit (AAKPV/E), causing an E863V substitution. A similar situation was also observed in several other virulence associated genes (P146, P159, P216, and LppT). We hypothesize that the cumulative effect of mutations in virulence associated genes may account for the attenuation of virulence in 168-L. In this study, a total of 330 genetic variations were identified. While these included reported virulence-related genes, other novel virulence determinants were also identified. However, further molecular genetics and in vivo studies are required to confirm and assess the relative importance of these suspected novel virulence determinants in the attenuation of virulence. The comparative genomic analysis presented here will not only provide insights into the basis of attenuation of virulence in 168-L, but may also provide targets for mutagenesis in the pursuit of development of a more efficacious vaccine.

Methods

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and DNA extraction

Clonal isolates of M. hyopneumoniae strain 168 and 168-L were selected for sequencing. Both of the strains were grown in KM2 cell-free medium at 37°C. The culture was harvested from 100 mL KM2 cell-free medium by centrifugation at 1,200×g for 30 min, and then total genomic DNA was extracted from mycoplasma cultures using a TIANamp Bacteria DNA Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Genomic libraries containing 8 kb inserts were constructed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Whole-genome sequencing of strain 168-L was performed by combining GS FLX and Solexa paired-end sequencing technologies. A total of 242,507 reads (67.4% paired ends) were produced with the GS FLX system, giving 44.5-fold coverage of the genome. Eighty-eight percent (215,346) of reads were assembled into one large scaffold using Newbler (454 Life Sciences, Branford, CT, USA). A total of 1,971,358 reads were generated with an Illumina Solexa genome analyzer IIx (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and were mapped to the scaffold with the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment (BWA) tool [53]. Gaps were filled by local assembly of the Solexa/Roche 454 reads or sequencing PCR products using a Prism 3730 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). All repeated DNA regions and low-quality regions were verified by PCR and sequencing of the product amplified from genomic DNA.

Annotation and sequence analyses

Open reading frames containing more than 30 amino acid residues were predicted using Glimmer 3.0 [54] with modified genetic code 4 and verified manually using the strain 168 annotation. Loci discrepancies between the 168 and 168-L consensus sequences were manually examined for support at the trace data level. Transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes were predicted using the tRNAscan-SE program [55] or by observing similarities with the M. hyopneumoniae strain 232 and strain J rRNA genes. Artemis (release 12) [56] was used to collate and annotate data. Functional predictions were based on BLASTP similarity searches against the UniProtKB [57], GenBank [58], Swiss-Prot protein [59], and COG [60] databases. EC numbers were assigned using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [67] and metabolic pathways were mapped and analyzed using KEGG Pathway Database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). Pseudogenes were detected by BLASTN analysis, comparing the genome sequences of 168-L with those of 232 and J, and then the annotation was revised manually.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis

Nucleotide comparisons and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis for strains 168 and 168-L were performed using the Artemis Comparison Tool (ACT) [61] and Mauve 2.3.1 genome alignment software [62]. ORF graphical visualization and manual annotation were carried out using Artemis, release 12 [56]. Screening for unusual coding differences between the 168 and 168-L genomes (stops and frame shifts) was conducted using FASTA program packages [63,64] and BLAST [65]. The coding differences between the 168 and 168-L genomes were checked manually.

Accession numbers

M. hyopneumoniae strains 168 and 168-L genome sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers CP002274.1 and CP003131, respectively.

Abbreviations

EP: Porcine Enzootic Pneumonia; SNVs: Single Nucleotide Variations; MPS: Mycoplasmal Pneumonia Of Swine; COG: Clusters Of Orthologous Groups; EC: Enzyme Classification; IS: Insertion Sequence; ICE: Integrative Conjugative Element; SSB: Single Strand Binding Protein; PTS: Phosphotransferase; BWA: Burrows-Wheeler Alignment; tRNA: Transfer RNA; rRNA: ribosomal RNA; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ACT: Artemis Comparison Tool.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: WL SX LF HC. Performed the experiments: WL ML SL SG ZF. Analyzed the data: WL ZZ GS RL BL. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: WL GS RL BL. Wrote the paper: WL LF SX. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Nucleotide differences identified between genomes of 168 and 168-L.

Insertions detected in 168-L compared to 168.

Deletions detected in 168-L compared to 168.

SNVs detected in 168-L compared to 168.

Annotated CDS of the elements ICEH168 and ICEH168-L.

Complete list of "168-L-specific" genetic variations in intergenic.

Mutations affecting genes with ABC transporter family signatures.

Contributor Information

Wei Liu, Email: liuwei85@webmail.hzau.edu.cn.

Shaobo Xiao, Email: vet@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Mao Li, Email: limao0226@yahoo.com.cn.

Shaohua Guo, Email: gsh1366765@163.com.

Sha Li, Email: lishayouxiang@yaoo.cn.

Rui Luo, Email: luorui@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Zhixin Feng, Email: zhixinf2000@yahoo.com.cn.

Bin Li, Email: libinana@126.com.

Zhemin Zhou, Email: z.zhou@ucc.ie.

Guoqing Shao, Email: 84391973@163.com.

Huanchun Chen, Email: chenhch@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Liurong Fang, Email: fanglr@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Lei Wang and members of his lab at Nankai University are thanked for their assistance with sequencing and analysis. We would also like to thank Dr. Maojun Liu at Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences for aid in Preparation of Materials. This study was supported by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (31170160, 31001080, and 31001066).

References

- Minion FC, Lefkowitz EJ, Madsen ML, Cleary BJ, Swartzell SM, Mahairas GG. The genome sequence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae strain 232, the agent of swine mycoplasmosis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7123–7133. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7123-7133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes D, Segales J, Meyns T, Sibila M, Pieters M, Haesebrouck F. Control of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae infections in pigs. Vet Microbiol. 2008;126:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razin S, Yogev D, Naot Y. Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev: MMBR. 1998;62:1094–1156. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1094-1156.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Young TF, Ross RF. Identification and characterization of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae adhesin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1013-1019.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minion FC, Adams C, Hsu T. R1 region of P97 mediates adherence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae to swine cilia. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3056–3060. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.5.3056-3060.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Wilton JL, Minion FC, Falconer L, Walker MJ, Djordjevic SP. Two domains within the Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae cilium adhesin bind heparin. Infect Immun. 2006;74:481–487. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.481-487.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos AT, Ferreira HB, Bizarro CV, Bonatto SL, Carvalho MO, Pinto PM, Almeida DF, Almeida LG, Almeida R, Alves-Filho L. et al. Swine and poultry pathogens: the complete genome sequences of two strains of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and a strain of Mycoplasma synoviae. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5568–5577. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5568-5577.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Young TF, Ross RF. Microtiter plate adherence assay and receptor analogs for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1616–1622. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1616-1622.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YZ, Ho YP, Chen ST, Chiou TW, Li ZS, Shiuan D. Proteomic comparative analysis of pathogenic strain 232 and avirulent strain J of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Biochemistry Biokhimiia. 2009;74:215–220. doi: 10.1134/S0006297909020138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto PM, Klein CS, Zaha A, Ferreira HB. Comparative proteomic analysis of pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains from the swine pathogen Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Proteome sci. 2009;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen ML, Puttamreddy S, Thacker EL, Carruthers MD, Minion FC. Transcriptome changes in Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae during infection. Infect Immun. 2008;76:658–663. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01291-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser M, Frey J, Bestetti G, Kobisch M, Nicolet J. Cloning and expression of a species-specific early immunogenic 36-kilodalton protein of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1217–1222. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1217-1222.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futo S, Seto Y, Okada M, Sato S, Suzuki T, Kawai K, Imada Y, Mori Y. Recombinant 46-kilodalton surface antigen (P46) of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae expressed in Escherichia coli can be used for early specific diagnosis of mycoplasmal pneumonia of swine by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:680–683. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.680-683.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JA, Browning GF, Markham PF. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae p65 surface lipoprotein is a lipolytic enzyme with a preference for shorter-chain fatty acids. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5790–5798. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5790-5798.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour LM, Jenkins C, Deutscher AT, Raymond BB, Padula MP, Tacchi JL, Bogema DR, Eamens GJ, Woolley LK, Dixon NE. et al. Mhp182 (P102) binds fibronectin and contributes to the recruitment of plasmin(ogen) to the Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae cell surface. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:81–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloy L, Vilei EM, Giacometti M, Frey J. Characterization of LppS, an adhesin of Mycoplasma conjunctivae. Microbiology. 2003;149:185–193. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett TA, Dinkla K, Rohde M, Chhatwal GS, Uphoff C, Srivastava M, Cordwell SJ, Geary S, Liao X, Minion FC. et al. P159 is a proteolytically processed, surface adhesin of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae: defined domains of P159 bind heparin and promote adherence to eukaryote cells. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:669–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton J, Jenkins C, Cordwell SJ, Falconer L, Minion FC, Oneal DC, Djordjevic MA, Connolly A, Barchia I, Walker MJ. et al. Mhp493 (P216) is a proteolytically processed, cilium and heparin binding protein of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:566–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary SJ, Walczak EM. Isolation of a cytopathic factor from Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1985;48:576–578. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.576-578.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepanek SM, Tulman ER, Gorton TS, Liao X, Lu Z, Zinski J, Aziz F, Frasca S Jr, Kutish GF, Geary SJ. Comparative genomic analyses of attenuated strains of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1760–1771. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01172-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Lu L, Wang B, Pu S, Zhang X, Zhu G, Shi W, Zhang L, Wang H, Wang S. et al. Genetic basis of virulence attenuation revealed by comparative genomic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Ra versus H37Rv. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Shao G, Liu M, Wu X, Zhou Y, Gan Y. Immune responses to the attenuated Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae 168 strain vaccine by intrapulmonic immunization in piglets. Agric Sci China. 2010;9:423–431. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(09)60113-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li P, Wang X, Yu Q, Yang Q. Co-administration of attenuated Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae 168 strain with bacterial DNA enhances the local and systemic immune response after intranasal vaccination in pigs. Vaccine. 2012;30:2153–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Feng Z, Fang L, Zhou Z, Li Q, Li S, Luo R, Wang L, Chen H, Shao G. et al. Complete genome sequence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae strain 168. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:1016–1017. doi: 10.1128/JB.01305-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen ML, Oneal MJ, Gardner SW, Strait EL, Nettleton D, Thacker EL, Minion FC. Array-based genomic comparative hybridization analysis of field strains of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7977–7982. doi: 10.1128/JB.01068-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto PM, de Carvalho MO, Alves-Junior L, Brocchi M, Schrank IS. Molecular analysis of an integrative conjugative element, ICEH, present in the chromosome of different strains of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Genet Mol Biol. 2007;30:256–263. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572007000200014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calcutt MJ, Lewis MS, Wise KS. Molecular genetic analysis of ICEF, an integrative conjugal element that is present as a repetitive sequence in the chromosome of Mycoplasma fermentans PG18. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6929–6941. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.6929-6941.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao G, Liu M, Sun P, Wang J, Du G, Zhou Y, Liu D. The establishment of an experimental swine model of swine mycoplasma pneumonia. J Microbes Infec. 2007;2:215–218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Young TF, Ross RF. Glycolipid receptors for attachment of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae to porcine respiratory ciliated cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4367–4373. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4367-4373.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski GC, Ross RF. Adherence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae to porcine ciliated respiratory tract cells. Amj Vet Res. 1993;54:1262–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski GC, Young T, Ross RF, Rosenbusch RF. Adherence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae to cell monolayers. Amj Vet Res. 1990;51:339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams C, Pitzer J, Minion FC. In vivo expression analysis of the P97 and P102 paralog families of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7784–7787. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7784-7787.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stakenborg T, Vicca J, Maes D, Peeters J, de Kruif A, Haesebrouck F, Butaye P. Comparison of molecular techniques for the typing of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae isolates. J Microbiol Meth. 2006;66:263–275. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro LA, Rodrigues Pedroso T, Kuchiishi SS, Ramenzoni M, Kich JD, Zaha A, Henning Vainstein M, Bunselmeyer Ferreira H. Variable number of tandem aminoacid repeats in adhesion-related CDS products in Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae strains. Vet Microbiol. 2006;116:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MB, Ekborg NA, Taylor LE, Hutcheson SW, Weiner RM. Identification and analysis of polyserine linker domains in prokaryotic proteins with emphasis on the marine bacterium Microbulbifer degradans. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1422–1425. doi: 10.1110/ps.03511604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker AL, Creamer TP. Polyproline II helical structure in protein unfolded states: lysine peptides revisited. Protein Sci. 2002;11:980–985. doi: 10.1110/ps.4550102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay BK, Williamson MP, Sudol M. The importance of being proline: the interaction of proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins with their cognate domains. FASEB J. 2000;14:231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher AT, Tacchi JL, Minion FC, Padula MP, Crossett B, Bogema DR, Jenkins C, Kuit TA, Walker MJ, Djordjevic SP. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae surface proteins Mhp385 and Mhp384 bind host cilia and glycosaminoglycans and are endoproteolytically processed by proteases that recognize different cleavage motifs. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:1924–1936. doi: 10.1021/pr201115v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheikh Saad Bouh K, Shareck F, Dea S. Monoclonal antibodies to Escherichia coli-expressed P46 and P65 membranous proteins for specific immunodetection of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in lungs of infected pigs. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:459–468. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.3.459-468.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Atmakuri K, Christie PJ. The outs and ins of bacterial type IV secretion substrates. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seubert A, Hiestand R, de la Cruz F, Dehio C. A bacterial conjugation machinery recruited for pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1253–1266. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipkovits L, Nicolet J, Haldimann A, Frey J. Use of antibodies against the P36 protein of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae for the identification of M. Hyopneumoniae strains. Mol Cell Probes. 1991;5:451–457. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8508(05)80017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MF, Heidari MB, Stull SJ, McIntosh MA, Wise KS. Identification and mapping of an immunogenic region of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae p65 surface lipoprotein expressed in Escherichia coli from a cloned genomic fragment. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2637–2643. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2637-2643.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkert MQ, Herrmann R, Schaller H. Surface proteins of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae identified from an Escherichia coli expression plasmid library. Infect Immun. 1985;49:329–335. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.329-335.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y, Hamaoka T, Sato S. Use of monoclonal antibody in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of antibodies against Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Isr J Med Sci. 1987;23:657–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks E, Faulds D. The Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae 74.5kD antigen elicits neutralizing antibodies and shares sequence similarity with heat-shock proteins. Vaccine. 1989;89:265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto PM, Chemale G, de Castro LA, Costa AP, Kich JD, Vainstein MH, Zaha A, Ferreira HB. Proteomic survey of the pathogenic Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae strain 7448 and identification of novel post-translationally modified and antigenic proteins. Vet Microbiol. 2007;121:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron J, Sawyer N, Ben Abdel Moumen B, Cheikh Saad Bouh K, Dea S. Species-specific monoclonal antibodies to Escherichia coli-expressed p36 cytosolic protein of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:528–535. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.4.528-535.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldimann A, Nicolet J, Frey J. DNA sequence determination and biochemical analysis of the immunogenic protein P36, the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:317–323. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-2-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey J, Haldimann A, Kobisch M, Nicolet J. Immune response against the L-lactate dehydrogenase of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in enzootic pneumonia of swine. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:313–322. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou SY, Chung TL, Chen RJ, Ro LH, Tsui PI, Shiuan D. Molecular cloning and analysis of a HSP (heat shock protein)-like 42 kDa antigen gene of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1997;41:821–831. doi: 10.1080/15216549700201861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen ML, Nettleton D, Thacker EL, Minion FC. Transcriptional profiling of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae during iron depletion using microarrays. Microbiology. 2006;152:937–944. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28674-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream MA, Barrell B. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert DB, Stoehr PJ, Stoesser G, Cameron GN. The European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3445–3449. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.17.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Rapp BA, Wheeler DL. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:15–18. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence data bank and its supplement TrEMBL in 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:49–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver TJ, Rutherford KM, Berriman M, Rajandream MA, Barrell BG, Parkhill J. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3422–3423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson WR, Lipman DJ. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson WR, Wood T, Zhang Z, Miller W. Comparison of DNA sequences with protein sequences. Genomics. 1997;46:24–36. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Nucleotide differences identified between genomes of 168 and 168-L.

Insertions detected in 168-L compared to 168.

Deletions detected in 168-L compared to 168.

SNVs detected in 168-L compared to 168.

Annotated CDS of the elements ICEH168 and ICEH168-L.

Complete list of "168-L-specific" genetic variations in intergenic.

Mutations affecting genes with ABC transporter family signatures.