On Monday nights, Quincy Brandt regularly gets together with a few friends in Winnipeg, Manitoba, to dine on food they salvaged from the trash.

Brandt, a 28-year-old university student, is part of a growing anticonsumer movement to rescue discarded food by dumpster diving, usually from bins behind supermarkets.

Brandt says he visits his “trap line” about once week, taking away prized items such as extra-creamy ice cream, king crab legs, fancy cheeses, dark chocolate, frozen hors d’oeuvres and pizza, and plenty of vegetables, fruit and fruit juices.

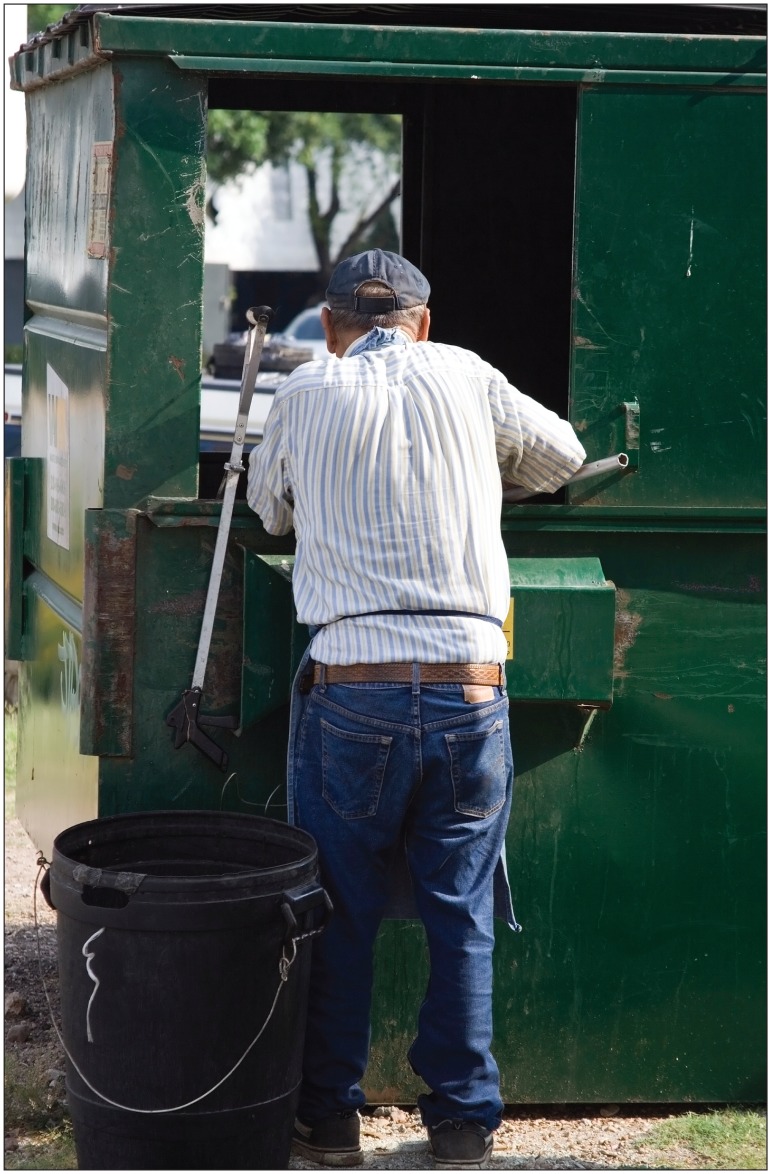

“Some dumpster divers use sticks for digging and lifting items out of the trash, but being young and agile, I usually jump in to access the very bottom,” says Brandt, a seasoned trash forager with five years’ experience.

Sometimes he wears protective hiking boots and gloves — other times he doesn’t.

Climbing inside a dumpster, sifting through the garbage and eating food without knowing where it’s been is risky behaviour that worries some public health officials and others in the food-safety field.

“There has to be a reason why people throw things out,” cautions Jim Chan, manager of food safety at Toronto Public Health in Ontario.

“It’s a very risky thing because we don’t know what’s in the garbage,” adds public health consultant Carla Eskow, a professor in the Environmental Health Department at Concordia University College in Edmonton, Alberta.

Dumpster diving poses many potential health risks, according to Eskow. These include possible cuts from nails, knives, glass and other sharp objects that can end up in the garbage. There is also a possibility of becoming ill from bacteria, especially in the summer; the dumpsters themselves breed bacteria and some are sprayed with pesticides. Food can also come into contact with chemicals and fecal matter, which can penetrate and infect open skin, Eskow says.

The health risks are greater for those who eat discarded food out of necessity, such as homeless people, than for “freegans,” who are generally younger and healthier.

Image courtesy of © 2013 Thinkstock

Chan adds that washing food does not guarantee these contaminants or chemicals will be eliminated.

Despite these risks, dumpster diving has become increasingly common in the last five years or so, with the growth of “freeganism” — food scavenging with aficionados, such as Brandt, who dumpster dive as a lifestyle choice to reduce waste, rather than out of necessity.

Freegans (a blend of “free” and “vegan,” although not all freegans are vegans) have brought a higher profile to an activity that has traditionally been the domain of low- or no-income garbage foragers, who dumpster dive for survival.

Eskow believes the health risks are greater for dumpster divers who eat discarded food out of necessity — such as homeless people — than they are for freegans, who often forage in groups, wear protective gear, have homes where they can wash their finds, and are generally younger, healthier, and therefore more immune to illness than those who live on the streets.

Thomas Kerr, a British Columbia researcher who has worked with drug addicts in Vancouver’s Downtown East-side, suspects that health problems — ranging from sprained ankles to stomach bugs and “horrible infections that start with a cut on the hand” — are not uncommon among homeless people or low-income earners who comb the trash for food. He says, however, that they are unlikely to seek medical treatment, or admit they became ill or injured from dumpster diving.

“It’s a hugely understudied phenomenon,” says Kerr, director of the Urban Health Research Initiative at the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS.

Brandt, for his part, says he does not believe he has ever been sick from food he has salvaged from dumpsters — although he stresses that he is cautious about his selections.

Despite warnings from public health officials, Chan and Eskow say there does not appear to be conclusive evidence that the risks associated with dumpster diving have actually translated into important health problems.

“I have been a health inspector for 30 years, and I don’t believe anything has come across my desk or from a database or from wherever that there has been somebody who ate food from a dumpster and became ill,” says Chan. All emergency departments, doctors’ offices, walk-in clinics and other health facilities in Toronto are expected to report cases of food-borne illness and their origins to public health.

Neither has Ottawa Public Health received any health complaints or concerns about dumpster diving, says spokesman Eric Leclair. “It is definitely not at the front of the line” of public health concerns, he says.

The perils of dumpster diving do not appear to be on the radar screen of national health organizations either. Spokespersons for the Canadian Health Care Association, the Canadian Public Health Association or the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians said they had no information or public statements about the risks.

However, the lack of reporting — and a shortage of studies — doesn’t mean that people don’t become ill or injured from the trash, cautions Chan.

“I don’t think anybody would disclose that information,” he says. “People eating food from a dumpster, that’s not something they’re going to volunteer.”

“My occasional sick days are like those of others,” says Brandt, who asserts that “the biggest risk of dumpster diving, in my view, is climbing up and down the bin.”