Abstract

The six biosurfactant-producing strains, isolated from oilfield wastewater in Daqing oilfield, were screened. The production of biosurfactant was verified by measuring the diameter of the oil spreading, measuring the surface tension value and emulsifying capacity against xylene, n-pentane, kerosene and crude oil. The experimental result showed three strains (S2, S3, S6) had the better surface activity. Among the three strains, the best results were achieved when using S2 strain. The diameter of the oil spreading of the biosurfactant produced by S2 strain was 14 cm, its critical micelle concentration (CMC) was 21.8 mg/l and the interfacial tension between crude oil and biosurfactant solution produced by S2 strain reduced to 25.7 mN/m. The biosurfactant produced by S2 strain was capable of forming stable emulsions with various hydrocarbons, such as xylene, n-pentane, kerosene and crude oil. After S2 strain treatment, the reduction rate of oil viscosity was 51 % and oil freezing point reduced by 4 °C.

Keywords: Biosurfactant, Emulsification activity, Interfacial tensions, Surface tension, Critical micelle concentration (CMC)

Introduction

The chemical synthesized surfactants have a wide range of applications in industries [1, 2]. However, the chemical synthesized surfactants are expensive and they causing environmental pollution. Biosurfactants are natural products produced by microorganisms. The biosurfactants have unique properties that chemical synthesized surfactants do not have, such as high surface activity, environmental friendliness, biodegradable and good anti-microbial activity at extreme temperatures, pH and salinity [3–5]. These advantages allow biosurfactants to be a substitute for chemical synthesized surfactants.

The potential development of a large number of biosurfactant-producing strains has been not found. The research on the breeding of high-yielding biosurfactant-producing strains has important significance. The most effective biosurfactant can reduce the surface tension of water from 72 mN/m to values in the range of 25-30 mN/m [6]. Therefore, the screening and evaluation of efficient biosurfactant-producing strains have wide biological and economic significance.

There are many areas of application where biosurfactants can be used, such as in industries and environmental restoration [7, 8]. Biosurfactants have uses in the petroleum industry, such as enhanced oil recovery and transportation of crude oil. Microbial enhanced oil recovery (MEOR) is estimated that this will be one of the most efficient methods in enhancing oil recovery in the future [9]. Biosurfactants can be produced from inexpensive and renewable resources [10, 11]. As the metabolites produced by microorganisms, biosurfactants have the ability to emulsify crude oil and to decrease the viscosity of crude oil that is one of the mechanisms for MEOR [12].

In this work, a new efficient biosurfactant-producing strain was screened. The preliminary properties of the biosurfactant including critical micelle concentration (CMC), oil spreading activity and emulsification ability were studied. The biosurfactants had the ability to reduce interfacial tensions between crude oil and biosurfactant solutions, to emulsify crude oil and to reduce the crude oil viscosity and freezing piont. These were the mechanisms for MEOR.

Materials and Methods

Microorganisms

The six biosurfactant-producing strains were isolated from oilfield wastewater in Daqing oil field. The six biosurfactant-producing strains were named as S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 and S6. The microorganisms were maintained at 4 °C on peptone agar slants and subcultured every month.

The Screening of Biosurfactant-Producing Strains

The nutrient medium was prepared with the following composition (g/l): (NH4)2SO4 10, KCl 1.1, NaCl 1.1, KH2PO4 3.4, K2HPO4 4.4, MgSO4·7H2O 0.5, FeSO4 2.5 × 10−5, Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetie Acid (EDTA) 1, yeast extract 0.5, liquefied paraffin 5, pH 7.2 in 1,000 ml distilled water. The oilfield wastewater (10 ml) was added into 250 ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 90 ml nutrient medium and cultivated at orbital shaking (180 rpm) at 37 °C for 72 h. The culture fluid was spread on the Cetyl Tri Ammonium Bromide (CTAB)-Methylene blue agar medium and cultivated at 37 °C for 9 d. The composition of CTAB-Methylene blue agar medium was (g/l): glucose 20, peptone 10, beef powder 1, CTAB 0.78, methylene blue 0.002, yeast extract 0.5, Agar 17, pH 7.2 in 1,000 ml distilled water. Then the halo of the colonies was extracted, streak on selective CTAB-Methylene blue agar medium and cultivated at 37 °C for 9 d. The composition of selective CTAB-Methylene blue agar medium was (g/l): glucose 20, peptone 10, beef powder 1, CTAB 5, methylene blue 0.02, yeast extract 0.5, Agar 17, pH 7.2 in 1,000 ml distilled water. The larger blue halo colonies were extracted streak on crude oil agar medium and cultivated at 37 °C for 9 d. The composition of crude oil agar medium was (g/l): (NH4)2SO4 1, NaNO3 2, MgSO4 0.3, KH2PO4 10, Na2HPO4 4, yeast extract 0.5, Agar 18.0, pH 7 in 1000 ml distilled water. The culture fluid was added into fermentation medium and cultivated at orbital shaking (180 rpm) at 37 °C for 72 h. The composition of fermentation medium was (g/l): NaNO3 5, KH2PO4 1, Na2HPO4 2, MgSO4 0.02, FeSO4 0.01, NaCl 5, CaCl2 0.08, glucose 20, yeast extract 0.1, pH 7.2 in 1,000 ml distilled water. The screened strains were streak on the crude oil agar medium. After two or three times plate streak, the pure strains could be separated and purified. All the medium was sterilized by autoclaving for 20 min at 121 °C.

Measurement of Oil Spreading Activity

Water (40 ml) was added into the culture dish of diameter (15 cm). Then it was dropped 2–3 drops liquid paraffin. After the stable oil film was formed, 2–3 drops zymotic fluid was added into the center of film center. Then the diameter of the oil spreading was measured.

Cellular Concentration

The growth of bacteria was monitored by measuring the optical density of the culture sample at 600 nm at different time. The optical density of the culture sample at 600 nm was measured by using a spectrophotometer of UV light visible (Genesys series 20). The concentration of biosurfactant (g/l) was measured using a calibration curve of biomass against optical density [13].

Measurement of Surface Tension, Interfacial Tension and CMC

The culture samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min to remove the bacteria cells. The effectiveness of the biosurfactant produced by six strains was determined by measuring the surface and interfacial tension of the samples at 25 °C, according to the Du Noüy Ring method [14]. The interfacial tension between crude oil and the cell-free cultures was determined by using a tensiometer (JK99B, Powereach, China) at reservoir temperature (45 °C). The CMC value was measured when the surface tension of the increasing biosurfactant concentrations first became minimum. The different concentration of biosurfactant was obtained by dissolving the isolated biosurfactant in distilled water. The CMC value was measured as mass per unit volume of biosurfactant (g/l).

Measurement of Emulsification Capacity

The emulsification capacity of biosurfactant was determined with the measurement of emulsification index (E24) [10]. Emulsifying activity was measured by adding 4 ml cell-free culture after 72 h fermentation into 6 ml hydrophobic compound (xylene, n-pentane, kerosene and crude oil) in a 10 ml screw-capped glass tube and shaken with a vortex for 2 min. After 24 h standing, the height of emulsion layer was measured and E24 was calculated.

|

where Ha is the height of the emulsion layer; Hb is the total height of the mixture.

Extraction of Biosurfactant

The culture samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min to remove the bacteria cells. The supernatant was added 6 M HCl to reach pH 2.0. Surfactin precipitation was formed by settling overnight at 4 °C. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 45 °C to obtain the crude surfactin. The crude surfactin was dissolved in deionized water (pH 8.0) to a finally pH 7 and extracted by a solvent having a 65:15 (v/v) chloroform-to-ethanol ratio at room temperature [9]. The organic phase was transferred to a round-bottom flask connected to a rotary evaporator to remove the solvent, yielding pure biosurfactant product.

Viscosity and Freezing Point of Crude Oil

Biosurfactant (50 ml) with crude oil (50 ml) in the conical flask was operated at the following parameters temperature 45 °C. After 7 days, crude oil was dehydrated. Then the viscosity of crude oil was measured by a Rotating Viscometer (NDS-8S, China) that was set at 50 °C and 12 s−1 shear rate. Crude oil dehydration after microbial treatment was used to measure freezing point by kryoscope.

Results and Discussion

Isolation of Biosurfactant-Producing Bacteria

The six biosurfactant-producing strains were obtained from oilfield wastewater. They were named S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 and S6. However, only three strains (S2, S3, S6) had the better surface activity after 7 days cultivation. The three isolates were selected for further study. The three isolated strains were selected based on morphological characteristics [15]. The diameter of the oil spreading, the characteristics and the interfacial tensions between crude oil and biosurfactant solutions of the six biosurfactant-producing strains were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of six strains grown in slant medium, the diameter of oil spreading of six strains and interfacial tension between crude oil and the cell-free culture broth from different six strains grown in fermentation medium for 60 h at 180 rpm and 45 °C

| Name | Colour | Colonial morphology | Macroshape | The diameter of oil spreading (cm) | Interfacial tensiona (mN/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Pinky | Globular shape | Smooth, moist | 2.8 | 36.8 ± 0.0 |

| S2 | Milky white | Short rod | Rough, moist | 14.0 | 25.7 ± 0.1 |

| S3 | Transparent | Roundness | Smooth, moist | 8.5 | 26.2 ± 0.2 |

| S4 | Milky white | Roundness | Smooth, moist | 4.5 | 31.8 ± 0.0 |

| S5 | Pinky | Roundness | Smooth, moist | 2.6 | 34.5 ± 0.1 |

| S6 | Milky white | Roundness | Smooth, moist | 7.6 | 28.7 ± 0.0 |

Surface tension was expressed as mN/m using fermentation medium as control (49.0 mN/m)

aValues are given as mean ± SD from triplicate determinations

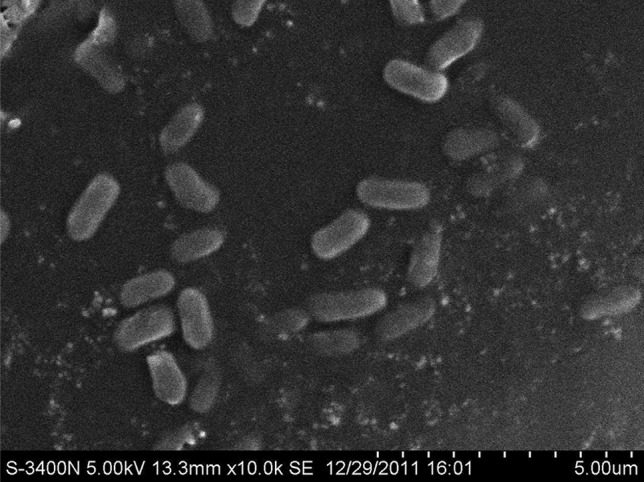

The best result was S2 strain, whose the diameter of the oil spreading was 14 cm and interfacial tension between crude oil and biosurfactant solutions of S2 strain reduced to 25.7 ± 0.1 mN/m (Table 1). Besides, S3 and S6 strain also had good result that the diameter of the oil spreading was 8.5 cm and 7.6 cm, respectively. The interfacial tension between crude oil and biosurfactant solutions of S3 and S6 strain reduced to 26.2 ± 0.2 and 28.7 ± 0.0 mN/m, respectively. The picture of the best biosurfactant-producing (S2 strain) under the scanning electron microscope was shown in Fig. 1. The size and shape of the bacteria under the scanning electron microscope was the same (Fig. 1). After purification, there was no other bacteria in the medium. The S2 strain was the pure bacteria.

Fig. 1.

Scanning electron microscopic picture of S2 strain (×10.0 K)

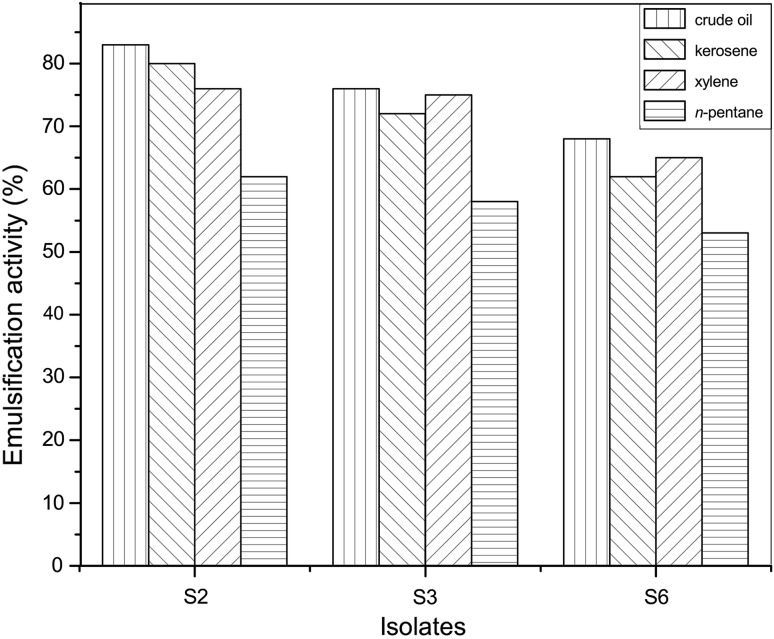

Emulsification Activity of the S2, S3, S6 Strains (E24)

The capability to stabilize an emulsion is an indication that the microorganism is producing biosurfactant [16]. Besides surface activity, good emulsification activity is also critical for biosurfactants application [1]. The emulsification indexes of S2, S3 and S6 strains formed between several typical hydrocarbons and cell-free supernatant of S2, S3 and S6 strains after 60 h cultivation at 37 °C were shown in Fig. 2. The S2 biosurfactant had the highest emulsification activity (E24, 83.0 %) on crude oil for the four kinds of hydrocarbons (Fig. 2). The second high emulsification activity is on kerosene, the third high emulsification activity is on xylene and the lowest emulsification activity (E24, 53.0 %) is on n-pentane (S6 strain). The biosurfactant produced by the S2 strain was more stable than the biosurfactant produced by the strain S3 and S6. The results indicated that the hydrocarbons, such as xylene, n-pentane, kerosene and crude oil, were all emulsified completely by the isolated biosurfactant produced by the S2, S3 and S6 strains. This implied that the biosurfactant produced by the S2, S3 and S6 strains could emulsify not only aromatic compounds but also short-chain and long-chain hydrocarbons.

Fig. 2.

Emulsification activity (E24) of various hydrocarbons, such as xylene, n-pentane, kerosene and crude oil, by biosurfactant produced by S2, S3, S6 strains

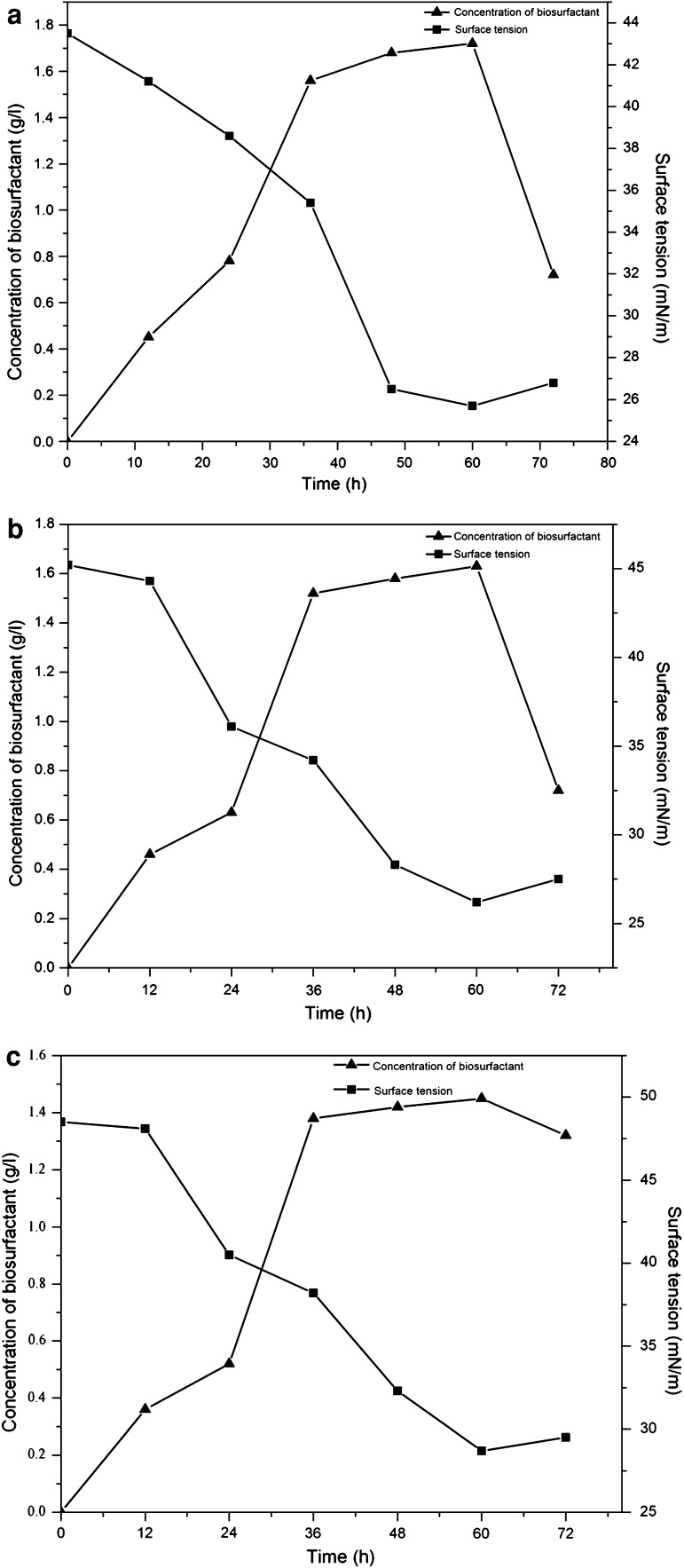

Cellular Concentration and Surface Tension

The growth and surface tension reduction of culture medium of the better three biosurfactant-producing strains were shown in Fig. 3. The exponential growth of the S2 strain was observed at about 24 h and the maximum biosurfactant production (1.72 g/l) occurred at 60 h (Fig. 3a). The surface tension of the cell free broth reached lowest value (25.7 mN/m). The exponential growth of the strain S3 was observed at about 24 h and after 60 h cultivation; the maximum biosurfactant production (1.63 g/l) was reached (Fig. 3b). The surface tension of the cell free broth reached lowest value (26.2 mN/m). The exponential growth of the S6 strain was observed at about 24 h and after 72 h cultivation; the maximum biosurfactant production (1.45 g/l) was reached (Fig. 3c). The surface tension of the cell free broth reached lowest value (28.7 mN/m). Biosurfactant production commenced at about 24 h, during the exponential phase, indicating its accumulation as primary metabolite during growth phase. Therefore, it concluded that the biosurfactants produced by S2, S3 and S6 strains were their primary metabolite, due to the production of growth-associated biosurfactant.

Fig. 3.

The growth curve of S2 (a), S3(b), S6 (c) strain and surface tension reduction of the cell-free culture broth from different six strains grown in a fermentation medium for 60 h at 180 rpm and 37 °C. Initial surface tension of the culture medium = 49.0 mN/m

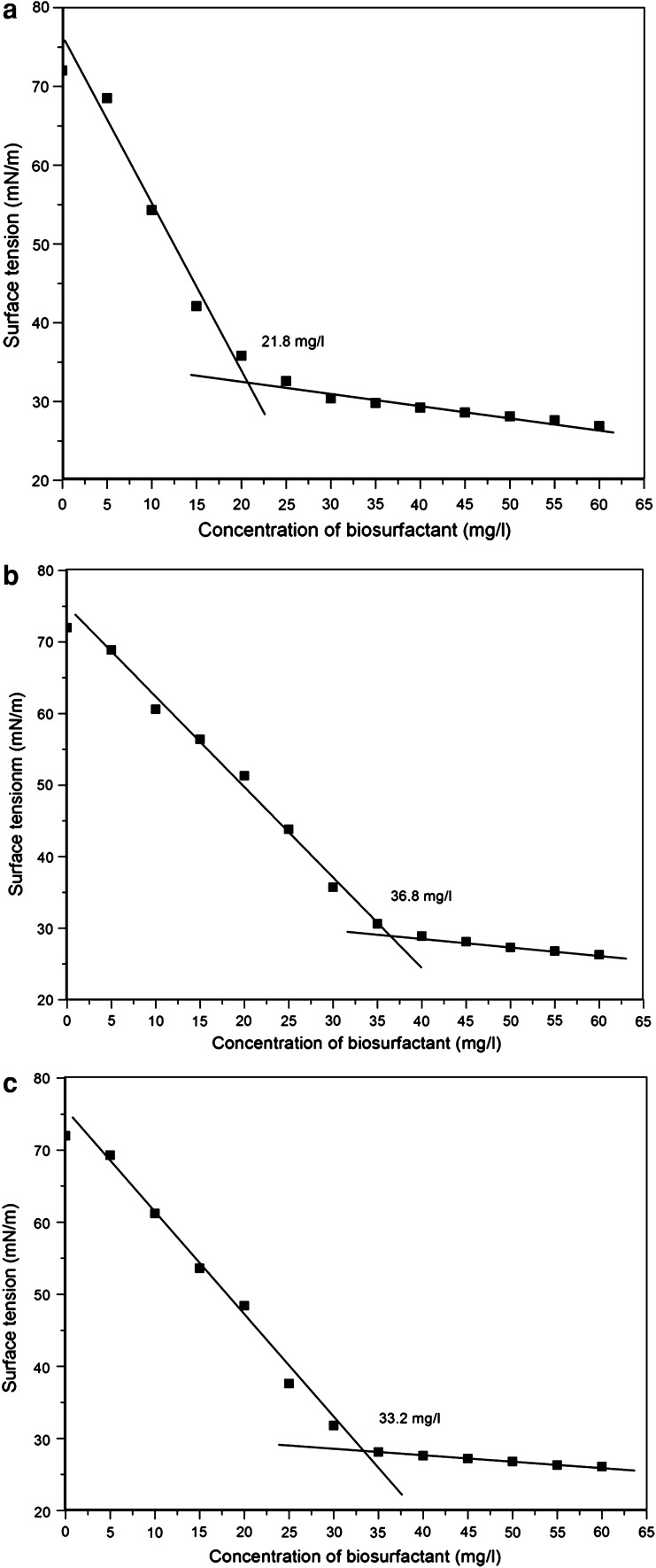

CMC Value

The CMC is an important parameter, which indicates the minimum concentration required for a biosurfactant solution to have a lower maximum surface tension. It can also define the solubility of a surfactant in the aqueous phase [13]. Indeed, even in the presence of a small concentration of biosurfactants, a CMC can be achieved, from which any variation in the surface tension can be observed [17]. The CMC of the biosurfactant produced by S2, S3 and S6 strains were shown in Fig. 4. The surface tension of biosurfactant decreased as its concentration increased until the CMC of the biosurfactant produced by S2, S3 and S6 strain was about 21.8, 36.8 and 33.2 mg/l, respectively (Fig. 4). The surface tension of the aqueous solution reduces to 34.2, 29.8, 30.1 mN/m. Compared with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) which has a CMC value of 2,100 mg/l [18], the CMC of the biosurfactants produced by S2, S3 and S6 strains were much lower than sodium dodecyl sulfate. This is the powerful evidence to prove that the found material contains a new biosurfactant. Because until now no information have been reported that biosurfactants have similar surface tension value as biosurfactant produced by S2 strain.

Fig. 4.

Surface tension of the free-cell broth as a function of biosurfactant concentration: S2 (a), S3 (b) and S6(c). The reference surface tension value = 72 mN/m

The Effect of Crude Oil by Biosurfactant-Producing Strain

The organic solvent and biosurfactant was produced during the metabolism, then crude oil was diluted by the organic solvent and crude oil was emulsified. So S2 strain had a definite effect on viscosity and freezing point of crude oil. The change of viscosity and freezing point was shown in Table 2. The reduction rate of oil viscosity was 51 % and the oil freezing point reduced by 4 °C (Table 2).

Table 2.

The change of the crude oil viscosity and freezing point at 50 °C

| Strain | Viscosity (mPa s) | The reduction rate of viscosity (%) | Freezing point (°C) | Freezing point depression values (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | |||

| S2 | 43.8 | 21.46 | 51.0 | 35.0 | 31.0 | 4.0 |

Conclusion

In this work, the six biosurfactant-producing strains were isolated from oilfield wastewater in Daqing oilfield. They were named S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 and S6. The experimental result showed three strains (S2, S3, S6) had the better biosurfactant activity. Among the three strains, the best results were achieved when using S2 strain. The biosurfactant produced by S2 strain had a large diameter of the oil spreading, high surface tension, good emulsifying properties and low critical micelle concentration. These are the powerful evidence to prove that the found material contains a new biosurfactant. For MEOR, the biosurfactant produced by S2 strain can emulsify oil and reduce oil viscosity, the oil freezing point and the interfacial tensions between crude oil and biosurfactant solutions. Further studies are under way to scale up growth conditions and to optimize biosurfactant production. An analysis of preparation for microbial enhanced oil recovery should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National High-technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (No.2008AA06Z304). The National High-technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (No.2008AA06Z304).

References

- 1.Banat IM, Makkar RS, Cameotra SS. Potential commercial applications of microbial surfactants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;53:495–508. doi: 10.1007/s002530051648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ewa K, Karolina C, Katarzyna BD, et al. The influence of rhamnolipids on aliphatic fractions of diesel oil biodegradation by microorganism combinations Indian. J Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12088-012-0323-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SH, Lim EJ, Lee SO, et al. Purification and characterization of biosurfactants from Nocardia sp. L-417. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2002;31:249–253. doi: 10.1042/BA19990111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva SNRL, Farias CBB, Rufino RD, et al. Glycerol as substrate for the production of biosurfactant by Pseudomonas aeruginosa UCP0992. Colloid Surf B. 2010;79:174. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thavasi R, Subramanyam Nambaru VRM, Jayalakshmi S, et al. Biosurfactant production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa from renewable resources. Indian J Microbiol. 2011;51(1):30–36. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0076-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal P, Sharma DK. Studies on the production of biosurfactant for the Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery by using bacteria isolated from oil contaminated wet soil. Pet Sci Technol. 2009;27:1880–1893. doi: 10.1080/10916460802686640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atipan S, Akio T, Vorasan S, et al. Mangrove sediment, a new source of potential biosurfactant-producing bacteria. Ann Microbiol. 2012;62:1669–1679. doi: 10.1007/s13213-012-0424-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghazaleh J, Iraj N, Sayyed HZE, et al. Enhancing compost quality by using whey-grown biosurfactant-producing bacteria as inocula. Ann Microbiol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somayeh E, Hamid R, Yaser ZS, et al. Evaluation of oil recovery by rhamnolipid produced with isolated strain from Iranian oil wells. Ann Microbiol. 2009;59:573–577. doi: 10.1007/BF03175148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nitschke M, Pastore GM. Production and properties of a surfactant obtained from Bacillus subtilis grown on cassava wastewater. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigues LR, Teixeira JA, Oliveira R. Low-cost fermentative medium for biosurfactant production by probiotic bacteria. Biochem Eng J. 2006;32:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2006.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Ji G, Tian J, et al. Functional characterization of a biosurfactant-producing thermo-tolerant bacteria isolated from an oil reservoir. Pet Sci. 2011;8:353–356. doi: 10.1007/s12182-011-0152-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sousa M, Melo VMM, Rodrigues S, et al. Screening of biosurfactant-producing Bacillus strains using glycerol from the biodiesel synthesis as main carbon source. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2012;35:897–906. doi: 10.1007/s00449-011-0674-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aparna A, Srinikethan G, Smitha H. Isolation, screening and production of biosurfactant by Bacillus clausii 5B. Res. Biotechnol. 2012;3(2):49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kshipra BD, Anupama PP, Mohan SK. Bacterial diversity of Lonar Soda lake of India. Indian J Microbiol. 2011;51(1):107–111. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0159-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batista SB, Mounteer AH, Amorim FR, et al. Isolation and characterization of biosurfactant/bioemulsifier-producing bacteria from petroleum contaminated sites. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobrinho HBS, Rufino RD, Luna JM, et al. Utilization of two agroindustrial by-products for the production of a surfactant by Candida sphaerica UCP0995. Process Biochem. 2008;43:912–917. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2008.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Wang XJ, Hu JD. Effect of surfactants on biodegradation of PAHs by white-rot fungi. Environ Sci. 2006;27:154–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]