Abstract

Nanoparticles (NPs) are of similar size to typical cellular components and proteins, and can efficiently intrude living cells. A detailed understanding of the involved processes at the molecular level is important for developing NPs designed for selective uptake by specific cells, for example, for targeted drug delivery. In addition, this knowledge can greatly assist in the engineering of NPs that should not penetrate cells so as to avoid adverse health effects. In recent years, a wide variety of experiments have been performed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying cellular NP uptake. Here, we review some select recent studies, which are often based on fluorescence microscopy and sophisticated strategies for specific labelling of key cellular components. We address the role of the protein corona forming around NPs in biological environments, and describe recent work revealing active endocytosis mechanisms and pathways involved in their cellular uptake. Passive uptake is also discussed. The current state of knowledge is summarized, and we point to issues that still need to be addressed to further advance our understanding of cellular NP uptake.

Keywords: nanoparticles, cellular uptake, endocytosis, exocytosis, drug delivery

1. Introduction

The widespread and steadily growing use of nanoparticles (NPs) and other nanomaterials in scientific [1] and commercial applications [2–5] entails their increasing proliferation and accumulation in the environment [6–9]. Thus, although a profound assessment of the risks to human health is not yet available, the chance of unintended human exposure is further increasing [10–16]. The fundamental interactions of nanomaterials with biomatter remain incompletely understood [11–16], largely due to a lack of mechanistic knowledge at the molecular level [11,17]. Even for intended therapeutic applications of NPs, possible health concerns need addressing [18–20]. This situation has spawned a large number of studies in recent years aimed at shedding light on the molecular interactions involved in the biological actions of NPs.

NPs are of similar size to typical cellular components and can efficiently intrude living cells by exploiting the cellular endocytosis machinery, resulting in permanent cell damage [20,21]. Only specialized cells such as macrophages are capable of phagocytosis, a form of endocytosis in which the cell engulfs larger particles. Almost all cells, however, can internalize NPs by pinocytosis. Four different basic pinocytic mechanisms are currently known, macropinocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolae-mediated endocytosis and mechanisms independent of clathrin and caveolin [22,23]. Physico-chemical properties of NPs including size [24,25], shape [24], surface charge [26–28] and surface chemistry [26,29,30] have been identified as strongly modulating the cellular uptake efficiency.

Upon incorporation by an organism, NPs interact with extracellular biomolecules dissolved in body fluids, including proteins, sugars and lipids prior to their encounter with the plasma membranes of cells. A layer of proteins forms on the NP surfaces, the so-called protein corona [10,31–43]. Consequently, cell surface receptors, which activate the endocytosis machinery, actually encounter NPs enshrouded in biomolecules rather than bare particles. This is an important issue for designing and engineering NPs with intentionally enhanced or suppressed cellular uptake.

In addition to intruding cells by active processes, NPs may also enter cells by passive penetration of the plasma membrane [44,45]. The ability of NPs to adhere to and penetrate cell membranes was shown to depend on their physical properties, including size, surface composition and surface charge [46–51]. Small, positively charged NPs were observed to pass through cell membranes, leading to membrane rupture and noticeable cytotoxic effects [52–55]. Even particles greater than 500 nm in diameter were reported to penetrate cell membranes by inducing strong local membrane deformations [56]. Membrane disruption can be reduced or even entirely avoided by a suitable design of the surface structure and charge density [46,57]. We note, however, that the surface properties of NPs within the organism may be significantly altered by the formation of a biomolecular adsorption layer.

Besides mere NP internalization, there is still another issue that is crucial for the assessment of biological consequences of NP exposure, namely their degradation in the biological environment. This may involve removal of the protein corona and, subsequently, a surface functionalization layer that often encloses an inorganic core particle. Exposure of the NP core to the corrosive intracellular milieu may result in its degradation and, eventually, its complete dissolution. The release of molecular debris and/or metal ions (e.g. Ag, Cd or In) will give rise to cytotoxic effects [58–60]. Adverse effects of NP incorporation will generally be a combination of ionic/molecular toxicity and toxicity aspects related to the particulate nature of the material. Recent studies of silver NPs with and without polymer surface coatings showed that formation of the protein corona strongly depended on the surface coatings around these NPs [40], whereas their severe cytotoxicity arose from the release of silver ions [61–63].

In recent years, there have been substantial activities to better understand the detailed molecular mechanisms involved in cellular NP uptake, often using fluorescence microscopy and other sophisticated biophysical techniques. In this review, we have selected a few recent studies that illustrate the approaches chosen to elucidate the molecular interactions promoting NP uptake. A thorough understanding of the involved processes at the molecular level will, on the one hand, greatly aid in the engineering of NPs that do not penetrate cells, which is relevant, for example, for NP-based contrast agents widely used in medical diagnosis. On the other hand, this knowledge is also important for developing NPs designed for selective uptake by specific cells, for example, for targeted drug delivery.

2. Effects of the protein corona on uptake efficiency

A variety of studies have reported effects of protein corona formation on the cellular response to NP exposure. For example, uptake of carboxyl-functionalized NPs by HeLa cells with adsorbed blood plasma proteins was shown to be strongly suppressed in comparison with bare NPs [64]. Immunoglobulin binding caused NP opsonization, thereby promoting receptor-mediated phagocytosis by macrophages [65]. Suppression of protein absorption onto NPs by coating them with polyethylene glycol (PEG) resulted in decreased uptake by macrophages [66] and longer circulation times as well as altered biodistribution upon injection in mice [65]. The adsorbed proteins are internalized by the cells together with the NPs and, therefore, may enter cellular compartments that they would not normally reach [67]. Understanding the formation and persistence of the protein corona on NPs is, therefore, critically important for the elucidation of cellular NP uptake.

To elucidate how the presence of a protein adsorption layer around NPs affects their cellular uptake, Jiang et al. [64] compared NP uptake by live HeLa cells in the presence or absence of human transferrin (TF) and human serum albumin (HSA) in buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, PBS) medium. Small (diameter approx. 10 nm), carboxyl-functionalized polymer-coated FePt NPs, fluorescently labelled by DY-636 dye molecules in the polymer shell, were used as model NPs. Protein concentrations of approximately 100 µM in the cell medium ensured complete coating of the NPs with these proteins, as was shown by binding studies using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS). The uptake of FePt NPs by live HeLa cells in PBS buffer was studied by quantitative confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Within minutes after exposing the cells to FePt NPs dissolved in PBS, the NPs accumulated on the cell membranes, and internalization took approximately 1 h to saturate. In the presence of 100 µM TF or HSA in the buffer, cellular uptake was significantly reduced. Control experiments were performed on fluorescently labelled (approx. 1 : 1 ratio) TF and HSA proteins to test the ability of HeLa cells to internalize these proteins without NPs. Uptake of TF, which is well known to be internalized via its cognate receptor, was significant, whereas HSA was barely endocytosed by HeLa cells under otherwise identical conditions.

The pronounced but comparable uptake suppression of NPs coated with TF and HSA was in marked contrast to the uptake behaviour of the individual proteins. Apparently, the TF layer on the NPs did not assist in their endocytosis, possibly because the cellular endocytosis machinery was occupied with internalization of the freely dissolved protein, which was present in 105-fold excess over the 1 nM NPs. Alternatively, binding of TF to the NPs may occur in such an orientation that its TF receptor binding site is concealed, so that triggering the receptor and subsequent uptake is precluded. For HSA, the protein corona may act as a protective layer, shielding the carboxyl-functionalized NP surface from direct interactions with receptors on the cell membrane. This work presents a vivid example how protein adsorption onto NPs markedly affects their uptake behaviour and underscores the need to understand NP–protein interactions at the molecular level.

Presently, our knowledge about conformational changes of the proteins upon adsorption onto NPs is still limited. For a number of serum proteins, Nienhaus and co-workers [36,64,68] have carefully measured the thickness of the protein corona on carboxyl-functionalized, polymer-coated NPs by using FCS. They found in all cases that the protein corona consisted of a protein monolayer that had a thickness that coincided with the dimensions of the adsorbed proteins binding in a specific orientation. These results suggest that the overall structure of the bound proteins was not markedly changed upon binding to the NPs. However, depending on the chemical nature of the protein–NP interaction, adsorption forces exerted on proteins may be sufficiently strong to distort or even completely disrupt the delicate architecture of these weakly stabilized, flexible macromolecules that are known to fluctuate among a vast number of conformational substrates at physiological temperatures [69,70]. In fact, protein structural changes, upon binding to NP surfaces, have been reported [10,39,40]. Conformational effects of adsorbed proteins were recently also addressed by Prapainop et al. [71], who observed that cellular uptake of NPs can be changed by a surface modification inducing protein misfolding in a component of the protein corona. For their study, they used fluorescent, hydrophobic CdSe/ZnS quantum dots (QDs) coated with amino-functionalized PEG and, for comparison, the same QDs modified by chemically attaching the inflammatory metabolite cholesterol 5,6-secosterol atheronal-B [72]. Antheronals are a class of oxysterol inflammatory metabolites [73] known to affect folding and aggregation state of several proteins, including apo-B100 [73], β-amyloid [74], α-synuclein [75] antibody light chains [76] and a murine prion protein [77]. Both QD types had the apolipoprotein apo-B100 in their hard protein corona after incubation in foetal calf serum [71,72].

Confocal fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry studies revealed a concentration- and time-dependent QD uptake of the antheronal functionalized QDs by murine macrophage-like cells (RAW 264.7), with a measureable QD uptake at particle concentrations down to 10 nM. By contrast, the antheronal-free QDs were not internalized by the cells even at higher concentrations (100 nM). From a comparison of antheronal-coated QD (100 nM) uptake after incubation for 2 h at 37°C in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium, supplemented with either foetal bovine serum (FBS, 1%, containing lipoproteins), lipoprotein-deficient serum (LPDS, 1%) or delipidated LPDS (1%), they concluded that low-density lipoprotein is required for cellular uptake.

With this study, Prapainop et al. [71] demonstrated that attaching small molecules to the NP surface led to misfolding of corona proteins, which then triggered NP uptake by specific cells that otherwise would not have done so. This study presents a vivid example that adsorption-induced structural changes of the proteins present in the corona may give rise to specific biological responses and underscores the importance of understanding NP–protein interactions in depth.

3. Cellular mechanisms involved in nanoparticle uptake

The effect of physico-chemical properties of NPs on their cellular uptake by different endocytosis mechanisms was thoroughly assessed by a variety of studies [24–30,78–81]. Recently, Kim et al. [82] studied the dependence of NP internalization on the cell cycle phase. The cell cycle consists of four phases during which the cell grows and divides. The G1 (or post-mitotic) phase is normally the major period of cell growth. The high demand of structural proteins and enzymes during this phase results in a high intracellular protein synthesis activity and a high rate of cell metabolism. The G1 phase is followed by the S (or synthesis) phase in which DNA is replicated. The subsequent G2 phase is again a period of cell growth and protein synthesis in preparation of mitosis. During the M (or mitotic) phase, the cell splits into two daughter cells. Both daughter cells will then have their own cell cycles starting with the G1 phase. Cells may temporarily stop their reproductive cycle and enter a resting phase, G0.

To test the effect of the cell cycle phase on NP uptake, Kim et al. [82] studied accumulation of NPs in human lung carcinoma cells (A549) that were incubated for up to 72 h with carboxyl-functionalized polystyrene NPs (PS-COOH, 40 nm diameter) with an overall negative ζ-potential (–34±1 mV in PBS/–2±1 mV in complete minimal essential medium, cMEM). These NPs were fluorescently labelled with a yellow-green dye similar to fluorescein isothiocyanate. By using confocal fluorescence microscopy, the NPs were observed to enter the A549 cells and to accumulate in lysosomes, as inferred from collocalization of the NP fluorescence, and the red fluorescence of lysosomes marked with the lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) antibody.

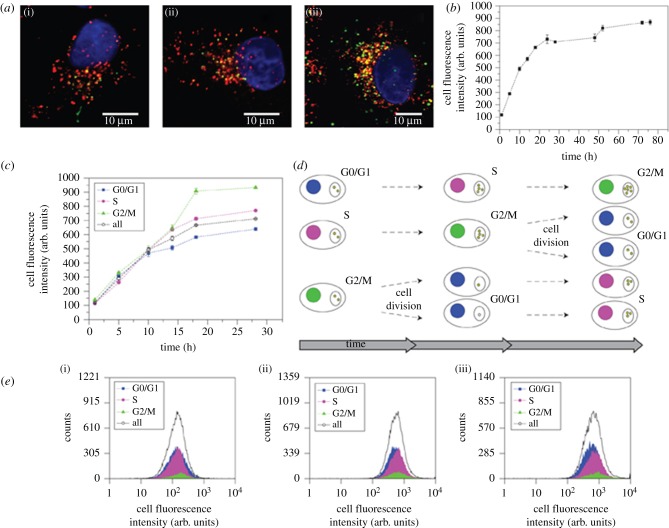

The mean intracellular fluorescence intensities were measured by using flow cytometry during the exponential growth phase of the cells to determine the uptake kinetics. Figure 1a shows confocal images of A549 cells that were continuously exposed to the PS-COOH NPs (25 μg ml−1) in cMEM for 5, 24 and 72 h, respectively. The time-dependent intracellular NP fluorescence intensity is shown in figure 1b. Because these data are averaged over all cells, they refer to a mixture of cells in different cell cycle phases.

Figure 1.

Study of the dependence of the cell cycle phase on the yield of internalization of 40 nm yellow-green PS-COOH (25 μg ml−1 in cMEM) NPs by A549 cells. (a) Confocal images were acquired after cell exposure to NPs for (i) 5, (ii) 24 and (iii) 72 h, respectively. Blue: cell nuclei (DAPI); red: lysosomes (LAMP1 antibody); green: NPs. (b) Time dependence of the mean cell fluorescence intensity as acquired by flow cytometry (error bars represent standard deviations over three replicates). (c) Time-dependent mean fluorescence intensities of A549 cells in the G0/G1, S and G2/M phases, respectively. (d) Schematic of time-dependent populations of the G0/G1, S and G2/M phases by cells and consequences for cellular NP content. (e) Flow cytometry distributions of cell fluorescence intensity after exposure times of (i) 2, (ii) 12 and (iii) 28 h to NPs, discriminating the different NP contents of cells in different phases of their cell cycle at the time point of the measurements. Adapted from Kim et al. [82]. Copyright 2011 Nature Publishing Group.

In a subsequent step, cells in the G0/G1, S or G2/M phases, respectively, were identified by DNA staining with 7-aminoactinomycin D, and DNA synthesis was monitored with the nucleoside analogue ethynyl deoxyuridine (5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine) so that contributions to the average of all cells (figure 1b) from cells in different phases of their cell cycles (figure 1c–e) could be assigned. The results indicated that the NP uptake yield did not depend on the cell cycle phase during the first 10 h of uptake.

Differences started to appear once the cells had divided during NP exposure. These cells in G0/G1 showed a reduced NP concentration compared with cells in the other phases (figure 1c–e). When cells that had divided under NP exposure began to populate the S phase, their intracellular NP concentration was again reduced when compared with cells in G2/M that had not yet divided at this point. This behaviour was also observed for other cell types (SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, 1321N1 astrocytoma cells and hCMEC/D3 cells) and different NPs in different media (40 nm yellow-green PS-COOH in serum-free medium, 40 nm yellow-green PS-COOH in complete medium, 100 nm yellow-green PS-COOH in complete medium and 50 nm green silica in complete medium).

These results can be understood by assuming that exocytosis is negligible in these experiments, and that the observed reduction is a mere consequence of cell division, during which the intracellular NP load is split between the daughter cells. Numerical simulations were found to agree with these interpretations. An intriguing aspect, as the authors noted [82], is that the observed NP dilution effect during cell division will likely be enhanced in tumour cells, owing to their generally enhanced cell division rate compared with non-cancerous cells. This effect can be relevant for NP-based cancer therapeutics and deserves further attention.

Although the in vivo consequences of these findings remain unclear, in vitro studies could be significantly affected. Environmental and even medical exposure scenarios normally involve markedly lower NP concentrations per cell than those used here and in most other in vitro studies of cellular NP uptake. Therefore, utmost caution needs to be exercised when arriving at conclusions from in vitro studies. For example, even a small exocytosis rate may become significant at lower NP concentrations and may efficiently counteract endocytosis. For a profound assessment of biological responses to NP exposure, in vivo conditions need to be approached as closely as possible.

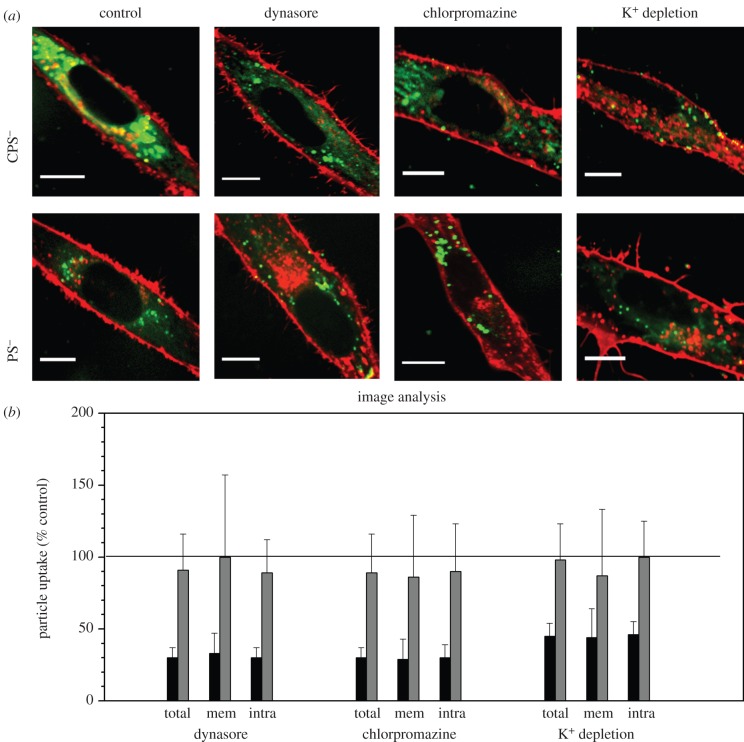

The specific endocytosis pathways involved in NP uptake can be revealed by means of inhibitory drugs that specifically interfere with one or the other pathway. By using this strategy, Jiang et al. [23] investigated the uptake of polystyrene NPs by mesenchymal stem cells using spinning-disc confocal optical microscopy combined with quantitative image analysis. These experiments were carried out in PBS buffer to avoid problems arising from protein adsorption onto the NPs. Two types of anionic polystyrene (PS) NPs with essentially identical sizes (approx. 100 nm) and ζ-potentials were compared: carboxyl-functionalized PS NPs (CPS) and plain PS NPs; both were coated in addition with anionic detergent for colloidal stabilization.

In contrast to smaller NPs (approx. 10 nm diameter), which accumulated on the cell membrane prior to internalization [64], the 10-fold larger polymeric NPs were not observed to adsorb onto the cell membrane (figure 2a), indicating that they were internalized as soon as they touched the membrane. CPS NPs internalized more rapidly and accumulated to a much greater extent inside the cells than plain PS NPs.

Figure 2.

Identification of specific endocytosis mechanisms involved in cellular uptake of carboxyl-functionalized (CPS) and plain polystyrene (PS) NPs by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) using inhibitory drugs. (a) Confocal fluorescence images of MSCs (red membrane stain) after 1 h incubation with 75 mg ml−1 NPs (green); without inhibitor (control) and in the presence of dynasore (80 mM), chlorpromazine (50 mM) or potassium depletion, respectively. (b) Quantified NP uptake (total, membrane-associated and intracellular fractions) in the presence of dynasore, chlorpromazine and potassium depletion (referenced to a control dataset without inhibitors), determined by quantitative image analysis. Black bars denote CPS; grey bars denote PS. Adapted from Jiang et al. [23]. Copyright 2011 Royal Society of Chemistry.

The presence of dynasore, a drug that suppresses endocytic processes involving dynamin, a large multi-domain protein involved in clathrin- and caveolin-mediated endocytosis [83], led to a significant uptake by approximately 70 per cent for CPS NPs in comparison with a control experiment without the inhibitor. However, no effect was observed for PS NPs under the same conditions (figure 2a). These observations were corroborated by quantitative image analysis (figure 2b), showing clearly that both the intracellular fractions and those close to the plasma membrane were affected to a similar degree. These results suggest that the carboxylic acid groups on the CPS NPs caused a strong preference for a dynamin-dependent endocytosis pathway. A comparable effect was observed with another inhibitory drug, chlorpromazine, known to interfere with clathrin-mediated endocytosis by disrupting the assembly of the clathrin lattice forming the endocytic pit at the plasma membrane [84]. The analysis (figure 2) showed that the uptake of CPS NPs was also suppressed by approximately 70 per cent, whereas again little effect was seen for PS NPs. Similar results were obtained with potassium-depleted cells as an alternative strategy for the inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis [85]. Uptake of CPS NPs was reduced by approximately 60 per cent, whereas the uptake of PS NPs was again unaffected (figure 2).

Taken together, the inhibition studies revealed that uptake of CPS NPs proceeded predominantly via dynamin- and clathrin-dependent pathways; the PS NPs apparently had a preference for dynamin- and clathrin-independent mechanisms. The observation that markedly different mechanisms were involved in the endocytosis of two types of NPs with identical properties, except for the surface functionalities, exemplifies that cellular uptake pathways and NP properties crucially depend on specific interactions with cell surface receptors, which subsequently activate different pathways.

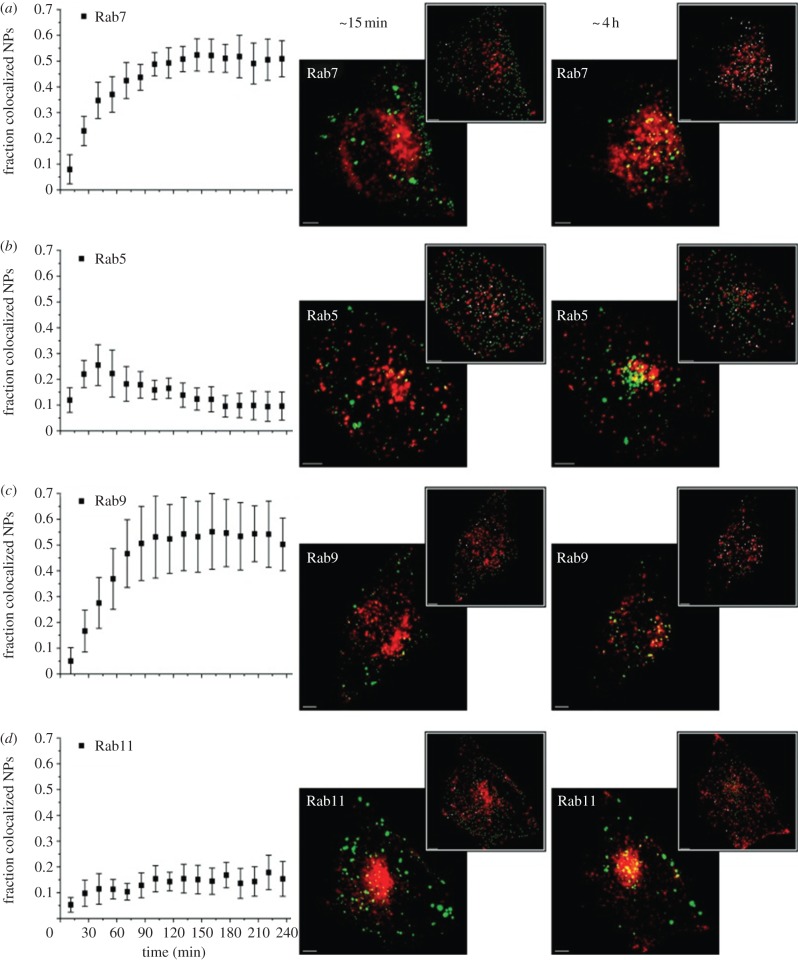

To elucidate intracellular trafficking of NPs, Sandin et al. [86] investigated collocalization of internalized NPs with Rab family GTPases. The Rab family of small GTPases is a major class of proteins regulating intracellular traffic [87]. Rab5A is typically the first Rab family GTPase encountered during endocytosis, mediating early endosome fusion [87,88]. Rab7 is essential for maturation of late endosomes and their subsequent fusion with lysosomes [89,90]; Rab9 is involved in the recycling of acid hydrolase receptors from late endosomes to the trans-Golgi network [91]; endocytic recycling processes involve Rab11A [92].

Sandin et al. [86] used 40 nm carboxylated polystyrene NPs in their study, carrying a negative ζ-potential of –12.3 mV in cDMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium plus 10% FBS), by live HeLa cells using spinning disc confocal microscopy. To visualize the Rab proteins, the cells were transfected with DNA encoding for fusion proteins of the earlier-mentioned Rab GTPases with the fluorescent protein mCherry to the specific Rab proteins [93].

The cells were subjected to a 1 min pulse of NPs followed by a chase in NP-free medium. Images were taken every 15 min for up to 4 h. The time-dependent collocalization profiles (figure 3) showed an increasing collocalization of NPs and Rab7 until a constant level was reached after approximately 90 min. For collocalization of NPs with Rab5, an initial increase peaking approximately 45 min after NP exposure was followed by a subsequent decline. The suggested interpretation for this behaviour was a transient occupancy of the NPs in Rab5-labelled membranes before their release into other endocytic intermediates.

Figure 3.

Time dependence of trafficking of carboxylated polystyrene NP (40 nm) through early endosomes to late endosomes and lysosomes, monitored by collocalization of NPs with (a) Rab7, (b) Rab5, (c) Rab9 and (d) Rab11 in HeLa cells. To the right, associated overlaid confocal fluorescence images (all scale bars represent 5 μm) of HeLa cells incubated with these NPs are shown, corresponding to the first (approx. 15 min) and last (approx. 4 h) point of the time profiles (red, Rab structures; green, NPs; yellow/white, colocalizing NP objects). Adapted from Sandin et al. [86]. Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

The collocalization profile with Rab9, however, was markedly different from the one acquired with Rab5. The increase in collocalization of NPs with this marker was coincident with the decline of collocalization with Rab5, indicating that the NPs become trapped in Rab9-positive structures.

Finally, a low degree of collocalization of NPs and Rab11A was measured, which suggests that the NPs used in this study are not quantitatively exocytosed. However, our earlier-mentioned caveat regarding the relevance of NP concentrations also applies here.

The experiments described here begin to shed light on the intracellular fate of NPs following their internalization. We conclude this section by pointing out that the chemical composition and, in consequence, other parameters such as pH of the immediate NP surroundings change dramatically during their transport through the endosomal pathway. The influence of such changes on the degradation of the protein corona or the NP itself as well as the influence of protein or ligand release into the cell interior as a consequence of possible exchange reactions on the NP surfaces are far from being thoroughly understood.

4. Dose dependence of nanoparticle uptake

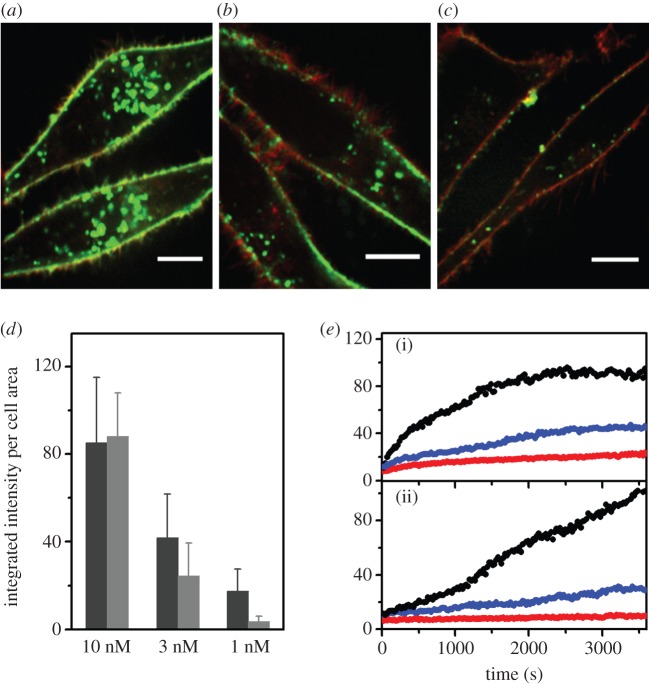

Intriguingly, small NPs (diameter approx. 10 nm) coat the plasma membrane before incorporation [64], whereas large NPs (100 nm) are directly internalized without any prior accumulation on the cell membrane [23]. A small NP may not be able to trigger endocytosis by itself because it interacts with an insufficient number of receptors. Thus, several NPs may be necessary to activate pit formation, and a nonlinear dependence of the uptake yield on the overall NP concentration should result. Jiang et al. [94] investigated this effect by monitoring the incorporation of 8 nm diameter d-penicillamine-coated quantum dots (DPA-QDs) by live human cancer (HeLa) cells. NP uptake was assessed quantitatively using spinning disc and 4Pi confocal microscopies. Following exposure of HeLa cells with PBS solution containing 10 nM DPA-QDs, cells were imaged for typically 1 h. Within 1 min, QDs were observed at the cell membrane and subsequently accumulated there. Over time, more and more QDs were internalized by the cells, forming large clusters in the perinuclear region within 1 h. A significant fraction of endocytosed QDs was localized in lysosomes, and some of these QD clusters were observed to actively being transported to the cell periphery for exocytosis. This report of a relevant exocytosis activity contrasts the claims of several other studies where exocytosis was found to be negligible [82,95–97]. In addition to the possible impact of NP concentration discussed earlier, NP size could be a decisive parameter for this behaviour as the DPA-QDs used in this study were considerably smaller than the NPs investigated in previous studies of NP exocytosis [82,95–97].

Confocal images taken after 1 h incubation at different QD concentrations (10, 3 and 1 nM; figure 4a–c) revealed the NP concentration dependence of the amount of DPA-QDs both at the plasma membranes and inside the cells. About equal amounts of QDs were associated with the cell membrane and found inside the cell after 1 h at 10 nM QD concentration.

Figure 4.

Dose-dependent uptake of DPA-QDs by HeLa cells. (a–c) Confocal fluorescence images of HeLa cells (scale bar: 10 μm) after 1 h exposure to PBS solutions containing DPA-QDs at concentrations of (a) 10, (b) 3 and (c) 1 nM. (d) Dose dependence of DPA-QD uptake by HeLa cells (after 1 h incubation), determined by quantitative analysis of membrane-associated (dark grey bar) and intracellular (light grey bar) fluorescence. (e) Kinetics of DPA-QD association with HeLa cells ((i) membrane-associated, (ii) intracellular) at particle concentrations of 10 (black), 3 (blue) and 1 nM (red). Adapted from Jiang et al. [94]. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

With decreasing QD concentration, the membrane-associated fraction decreased in a linear fashion with the NP concentration, whereas the intracellular fraction decreased much more strongly. Kinetic analysis of these processes (figure 4d,e) lent further support to these findings [94]. With 1 nM NP concentration, only very few bright spots were visible inside the cells. These results support the notion that, for very small NPs, a critical threshold density of QDs on the cell membrane has to be exceeded to trigger the internalization process. This study again underscores the importance of understanding dosage effects on NP uptake and intracellular fate. This issue is challenging to address because only a few highly sensitive and sophisticated methods are available for studies at particle concentrations comparable to those of relevant exposure scenarios.

Further issues of particle dosage during in vitro studies arise from the consequences of NP degradation, which can significantly affect the results of such experiments [10,39,61,98,99]. The problem of NP stability in biological environments, containing high concentrations of proteins and ions, was also investigated by Treuel and co-workers [39], who studied the influence of a protein corona formation around initially citrate stabilized silver NPs on their colloidal stability. Their NPs were further stabilized by the formation of a protein corona, and this effect could be used to measure protein binding affinities to the NP surfaces [39].

Most in vitro experiments studying cellular uptake of NPs expose cells at the bottom of a culture plate. Xia and co-workers [99] studied the effect of NP sedimentation and diffusion on the cellular uptake of gold NPs (nanospheres, nanocages and nanorods) by human breast cancer cells (SK-BR-3, ATCC HTB-30). They compared uptake efficiencies of their particles in a classical upright set-up to data acquired in an inverted set-up with cells being positioned at the ceiling of the culture chamber and observed a higher uptake of NPs in the upright configuration compared with the inverted set-up. Not surprisingly, this difference increased with the sedimentation velocity of their NPs.

Controlling the NP dosage is important for obtaining meaningful results in both in vivo and in vitro experiments. Besides NP degradation during the experiment, NP transport in the extracellular medium, notably sedimentation, may result in an erroneous result for NP uptake. This issue presents additional complications when comparing results obtained with other NPs with dissimilar sedimentation characteristics.

5. Modelling forces acting on membrane-bound nanoparticles

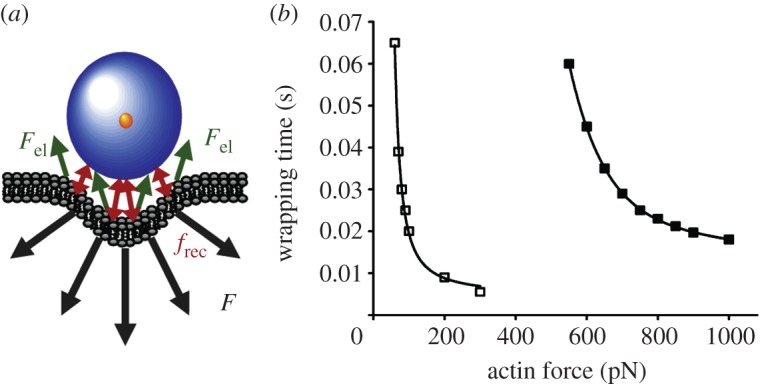

The interpretation of experimental results from cellular uptake studies can be facilitated by quantitative modelling of the observed behaviour. Lunov et al. [19] used carboxydextran-coated superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs of 60 nm (SPIO) and 20 nm (USPIO) diameters that are widely used as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging. They analysed the uptake of these NPs by human macrophages and found that endocytosis occurred via a clathrin-mediated, scavenger receptor A-dependent mechanism. Intriguingly, they also measured NP uptake as a function of time and presented a mathematical model that allows several mechanistic parameters to be estimated. This model describes internalization by initial binding of NPs to receptors and subsequent wrapping a membrane patch around them for internalization. The overall uptake was assumed to be governed by the wrapping time, τw, whereas earlier models [100] had suggested that NP diffusion through the membrane controls the wrapping time.

By using quantitative confocal fluorescence microscopy, the time dependence of NP uptake, N(t), was observed to be exponential,

| 4.1 |

where NS is the number of NPs at saturation (approx. 107), and T is the characteristic time (approx. 1 h). At short times after exposing the cells to the NPs, the uptake rates, dN(0)/dt, for SPIO and USPIO were approximately 25 000 and approximately 2500 s−1, respectively. The overall uptake rate per cell, dN/dt, can be recast into the rate per individual clathrin-coated pit-forming event, dn/dt,

| 4.2 |

by introducing two parameters, the lateral dimension of the macrophage, L (approx. 20 µm), and the characteristic footprint of an individual endocyting pit, a. However, neither dn/dt nor a are directly accessible from kinetic experiments on entire cells. The rate dn/dt, however, is the inverse of the uptake time, which may be approximated by the wrapping time, τw. A simple force model was introduced to calculate the wrapping time (figure 5a),

| 4.3 |

Figure 5.

Quantitative model of cellular uptake of NPs according to Lunov et al. [19]. (a) Schematic of the forces acting on NPs during endocytosis. F, total force from the cytoskeleton; Fel, elastic forces of the deformed membrane; frec, receptor interactions ensuring NP attachment during incorporation. (b) Calculated wrapping time (individual uptake time) of NPs as a function of the force exerted by the cytoskeleton. Black squares denote SPIO; white squares denote USPIO. For details, see the text. Adapted from Lunov et al. [19]. Copyright 2011 Elsevier.

Here, the total force that the cytoskeletal actin structure has to exert along the direction perpendicular to the membrane, F(x), consists of the elastic membrane deformation force, Fel(x), and the viscous drag force, which depends on the cytoplasmic viscosity, η, the particle radius, R and the velocity, dx/dt. The attachment of the NP during incorporation has to be ensured by receptor interactions (frec in figure 5a). From these calculations, τw was obtained as a function of F(x), as shown in figure 5b. For the same actin force, the model reveals that SPIO and USPIO wrapping times differ by a factor of approximately 10. The rate of individual uptake events, dn/dt, can be estimated as 10–100 s−1, yielding reasonable values of 0.3–4 µm for the characteristic length scale a associated with clathrin-coated pits. Given that the overall number of receptors per cell is (2–4) × 104 [101], one concludes that approximately 2–20 receptors are involved in NP binding during an individual endocytosis event.

Overall, the analysis of the experimental data obtained by confocal microscopy using the model presented by Lunov et al. [19] produced reasonable parameters and emphasized the value of even rather simplistic physical models for furthering our understanding of complex biological processes.

6. Passive mechanisms of nanoparticle uptake by cells

In addition to active cellular uptake, NPs may also translocate passively through cellular membranes. These processes may remain unnoticed because active endocytosis often predominates. To focus on passive transport of NPs across cellular membranes, red blood cells (RBCs) have frequently been used as model systems [44,45,102,103] because these cells are highly specialized and lack a cell nucleus, most organelles and the endocytic machinery [104].

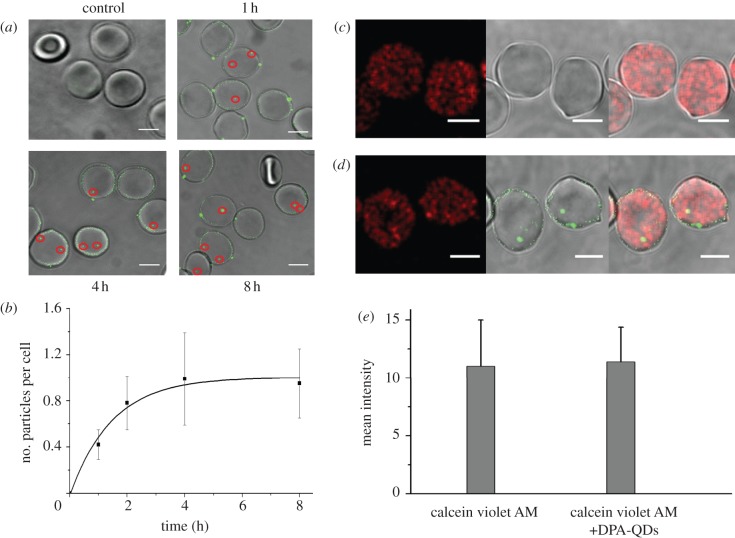

Recently, Wang et al. [44] studied interactions between DPA-QDs and RBCs. DPA is a small, zwitterionic amino acid ligand and the charges on the amino and carboxylic acid groups are balanced at neutral pH. RBCs were incubated with 10 nM DPA-QDs in PBS solution for different time periods and subsequently centrifuged the solution to separate free DPA-QDs from the RBCs. The sedimented cells were then transferred into a microscope sample cell and imaged using confocal fluorescence microscopy. In figure 6a, overlaid bright-field and fluorescence confocal images are shown for a control sample (without DPA-QD exposure) and for samples incubated with DPA-QDs for 1, 4 and 8 h. They clearly reveal that DPA-QDs adhere to RBC membranes, and the number of fluorescence spots, either close to the cell membranes or inside the cells, increases with exposure time.

Figure 6.

Cellular uptake of NPs by red blood cells (RBCs) via passive membrane penetration. (a) Overlay of bright-field and confocal fluorescence images (scale bar: 5 μm) of DPA-QD internalization by RBCs after incubating with PBS (control) and 10 nM DPA-QDs for 1, 4 and 8 h. (b) Normalized fluorescence intensity of intracellular bright spots plotted as a function of time. (c,d) Images from fluorescence microscopy experiments (scale bar: 5 μm) probing the integrity of the RBCs plasma membrane during DPA-QD uptake. RBCs were incubated with (c) calcein violet AM, and subsequently (d) with 10 nM DPA-QDs for 6 h. (e) Mean fluorescence intensities of calcein violet AM labelled cells. Adapted from Wang et al. [44]. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

The internalization kinetics was calculated from the integrated fluorescence intensity of the internal spots (figure 6a, red circles), and a normalization to the cellular area in the observation plane was applied to account for the different dimensions of the cells (figure 6b). For the internalized fraction, a half-life of 1.7 h was determined. The images showed that the adsorbed DPA-QDs did not induce a strong local membrane deformation and that penetration of DPA-QDs into RBCs apparently did not disturb the integrity of the membrane. Naturally, these statements only hold for spatial scales that can be resolved by optical microscopy.

The integrity of the RBC membrane during DPA-QD internalization was examined by observing possible escape of a tracer dye from the cytosol. RBCs were preincubated with calcein violet AM, a cell-membrane-permeant dye that becomes impermanent after hydrolysis by intracellular esterases. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with DPA-QDs for 6 h (figure 6c,d). The data clearly showed that internalization of DPA-QDs did not cause any detectable loss of cellular fluorescence from the dye, suggesting that the RBC membranes remained largely intact during NP penetration of the bilayer.

These data were further complemented by electrochemical studies of the interaction between DPA-QDs and a planar model membrane. Briefly, vesicles with the lipid content of the outer or inner leaflets of the RBC lipid bilayer were fused onto a gold electrode by the interaction between the vesicles and the hydrophobic surface of a self-assembled monolayer of 1-dodecanethiol (DT) pre-adsorbed onto the electrode. With these bilayers prepared on a gold electrode, cyclic voltammograms of 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3− in a solution of 0.1 M KCl were acquired before and after treating the membrane with DPA-QD solution for several hours. A leakage current owing to the presence of NPs was not detectable, supporting the notion that the presence of DPA-QDs does not cause pores to form in the outer and inner lipid layers of the model membrane, which would allow ions to penetrate the bilayer and diffuse to the gold electrode.

Moreover, surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS) was carried out on the same model membrane preparation. SEIRAS allows infrared spectra to be acquired from extremely thin molecular layers by using the strong enhancement of the infrared absorption of molecules in near-field distance to nano-structured metal films [105,106]. The analyses of the frequencies of the stretching modes of the CH2 groups in the lipid tails revealed that the bilayer structure is softened in the presence of DPA-QDs interacting with either side of the model membrane. Its higher dynamics may facilitate penetration of DPA-QDs into the lipid bilayer without pore formation.

As was shown earlier [46,57], NP-induced hole formation in a membrane can be avoided by suitably modulating the NP surface charge density or structure. Cationic Au NPs with 50 per cent charge density (relative to hydrophobic ligands) effectively penetrated the lipid membrane without forming holes, whereas significant membrane disruption occurred at higher charge densities [46,57]. Certain cell-penetrating peptides are also known to translocate across membranes without lipid bilayer disruption [107–109]. The zwitterionic functionalization of the DPA-QDs used by Wang et al. [44] may be responsible for the ability of these NPs to penetrate lipid membranes without compromising bilayer integrity.

7. Conclusions and outlook

The results discussed in this review have a number of implications for the field of NP exposure to cells and entire organisms, including humans. The first consequence of such exposure is usually a protein adsorption layer that forms around NPs upon their exposure to biofluids that can markedly modify cellular uptake [10,64]. The current state of knowledge is, however, still incomplete, especially with respect to the detailed physico-chemical processes occurring at the molecular level. The kinetics of corona formation, stability and ageing effects need further attention, especially under complex biological conditions, with proteins exchanging with a multitude of competing proteins, is still only poorly understood [10,110–113]. We stress the need to bridge the gap between the in vitro results, acquired under highly controlled conditions, and the in vivo consequences.

Little is known yet about the change of protein structure upon adsorption. It depends both on the nature of the adsorbing protein and on the NP surface [10,39–41]. On some NP surfaces, a particular protein may stay native-like, whereas other surfaces may cause severe denaturation. To coat NP surfaces with small molecules that give rise to denaturation of particular corona proteins [71] can be extremely useful for understanding the in vitro behaviour of NPs. For application in vivo, however, we also need to know how ligands or denatured corona proteins are exchanged on relevant timescales.

It is by now well established that NP uptake occurs mainly via the endocytic machinery of the cell [22,23,45]. Simple physical models have been developed and tested that can reveal key parameters of endocytosis. Quantitative modelling, however, is still at an early stage and awaits further development. For smaller NPs, a critical threshold density on the cell membrane has to be exceeded to trigger the internalization process, as inferred from the nonlinear dependence of the uptake on NP concentration [94]. Quantitative details of such threshold densities and their dependence on NP characteristics are still missing. Frequently, in vitro uptake experiments are carried out with higher NP concentrations than those expected for environmental exposure of cells. However, such conditions may bear relevance in biomedical applications. Especially for targeted drug delivery, it is of utmost importance to know the uptake yields at particular NP concentrations as well as the specific pathways that are used by the NPs.

Intracellular pathways have been revealed for a variety of NPs as, for instance, by the study reviewed here using collocalization of NPs with Rab-family GTPases [86]. How the intracellular fate of NPs can be controlled by their properties is a further important issue for successful drug delivery strategies and, likewise, for a reduction of NP toxicity.

The ability of NPs to adhere to and penetrate cell membranes by processes that do not involve any active uptake machinery of the cell is well documented. Overall, the way in which NP surface properties govern their behaviour in passive uptake has not yet been thoroughly characterized. Passive uptake routes may well play an important role during long-term exposure to low NP concentrations. Whenever threshold densities of NPs on cellular membranes are not reached, passive uptake of NPs may become a significant contribution to their overall internalization.

The impact of cell division on the NP load within cells is another issue that needs attention. Especially, for targeted delivery of NPs to cancer cells, the effect of cell division on intracellular particle concentrations was pointed out to be potentially crucial, as cancer cells often divide faster and, thus, reduce their NP load faster, than the surrounding non-cancerous cells [82]. However, the relative timescales of NP uptake and cell division have to be considered, in addition to the acute NP toxicity, to assess the relevance of this effect in different exposure scenarios.

We have also discussed the importance of a detailed characterization of colloidal stability in any NP studies and its consequences for NP uptake yields in biological studies. This is very relevant for in vitro studies and can also be relevant in biomedical exposure with high NP concentrations. In most environmental exposure situations, the NP concentration will likely be so low that extracellular agglomeration of NPs would occur on a much longer timescale than cellular uptake, reducing the relevance of this effect.

To conclude, thanks to substantial efforts by many laboratories, general mechanisms of NP uptake by cells have been identified, and correlations between uptake behaviour and NP properties have been observed, although many details remain to be explored. The importance of specific interactions between NPs and cell surface receptors has been shown, but the effects of physical and chemical properties of the NP surfaces deserve further attention. The key relevance of the protein corona in modulating cellular interactions has been recognized, but still very little is known about the dynamics of protein adsorption onto NPs in complex biological fluids, protein conformational changes associated with corona formation and the ensuing effects on cellular responses. Considering the wide variety of existing NPs and relevant cell types, substantial variations in their mutual interactions can be expected, and much work remains to be done.

Acknowledgements

L.T. and G.U.N. acknowledge financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through the Center for Functional Nanostructures and Schwerpunktprogramm 1313. X.J. acknowledges grant support by the Youth Foundation of China (21105097), President Funds of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

References

- 1.Ye-Qin Z, Wang Y-F, Jiang X-D. 2008. The application of nanoparticles in biochips. Recent Patent Biotechnol. 2, 55–59 10.2174/187220808783330938 (doi:10.2174/187220808783330938) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD 2008. Current developments/activities on the safety of manufactured nanomaterials. Paris, France: OECD [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roco MC. 2008. The journal of nanoparticle research at 10 years. J. Nanoparticle Res. 10, 1–2 10.1007/s11051-008-9528-3 (doi:10.1007/s11051-008-9528-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aitken RJ, Chaudhry MQ, Boxall ABA, Hull M. 2006. Manufacture and use of nanomaterials: current status in the UK and global trends. Occup. Med. 56, 300–306 10.1093/occmed/kql051 (doi:10.1093/occmed/kql051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anselmann R. 2001. Nanoparticles and nanolayers in commercial applications. J. Nanoparticle Res. 3, 329–336 10.1023/A:1017529712314 (doi:10.1023/A:1017529712314) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handy RD, Henry TB, Scrown TM, Johnston BD, Tyler CR. 2008. Manufactured nanoparticles: their uptake and effects on fish: a mechanistic analysis. Ecotoxicology 17, 396–409 10.1007/s10646-008-0205-1 (doi:10.1007/s10646-008-0205-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiesner MR, Lowry GV, Alvarez P, Dionysiou D, Biswas P. 2006. Assessing the risks of manufactured nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 4336–4345 10.1021/es062726m (doi:10.1021/es062726m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen R, Depledge M. 2005. Nanotechnology in the environment: risks and rewards. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 50, 609–612 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.05.001 (doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreyling WG, Semmler M, Möller W. 2004. Dosimetry and toxicology of ultrafine particles. J. Aerosol Med. 17, 140–152 10.1089/0894268041457147 (doi:10.1089/0894268041457147) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treuel L, Nienhaus GU. 2012. Toward a molecular understanding of nanoparticle–protein interactions. Biophys. Rev. 4, 137–147 10.1007/s12551-012-0072-0 (doi:10.1007/s12551-012-0072-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas K, Cydzik I, Del Torchio R, Farina M, Forti E, Gibson N, Holzwarth U, Simonelli F, Kreyling W. 2010. Radiolabelling of TiO2 nanoparticles for radiotracer studies. J. Nanoparticle Res. 12, 2435–2443 10.1007/s11051-009-9806-8 (doi:10.1007/s11051-009-9806-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller KH. 2007. Nanotechnology and society. J. Nanoparticle Res. 9, 5–10 10.1007/s11051-006-9193-3 (doi:10.1007/s11051-006-9193-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maynard AD, et al. 2006. Safe handling of nanotechnology. Nature 444, 267–269 10.1038/444267a (doi:10.1038/444267a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nel A, Xia T, Mädler L, Li N. 2006. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science 311, 622–627 10.1126/science.1114397 (doi:10.1126/science.1114397) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Service RF. 2006. Priorities needed for nano-risk research and development. Science 314, 45. 10.1126/science.314.5796.45 (doi:10.1126/science.314.5796.45) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnard AS. 2006. Nanohazards: knowledge is our first defence. Nat. Mater. 5, 245–248 10.1038/nmat1615 (doi:10.1038/nmat1615) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Handy RD, von der Kammer F, Lead JR, Hassellöv M, Owen R, Crane M. 2008. The ecotoxicology and chemistry of manufactured nanoparticles. Ecotoxicology 17, 287–314 10.1007/s10646-008-0199-8 (doi:10.1007/s10646-008-0199-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linse S, Cabaleiro-Lago C, Xue W-F, Lynch I, Lindman S, Thulin E, Radford SE, Dawson KA. 2007. Nucleation of protein fibrillation by nanoparticles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 8691–8696 10.1073/pnas.0701250104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0701250104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunov O, Zablotskii V, Syrovets T, Röcker C, Tron K, Nienhaus GU, Simmet T. 2011. Modeling receptor-mediated endocytosis of polymer-functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles by human macrophages. Biomaterials 32, 547–555 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.111 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.111) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lunov O, Syrovets T, Röcker C, Tron K, Nienhaus GU, Rasche V, Mailänder V, Landfester K, Simmet T. 2010. Lysosomal degradation of the carboxydextran shell of coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and the fate of professional phagocytes. Biomaterials 31, 9015–9022 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.003 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asha Rani PV, Low Kah Mun G, Hande MP, Valiyaveettil S. 2008. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells. ACS Nano 3, 279–290 10.1021/nn800596w (doi:10.1021/nn800596w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conner S, Schmid SL. 2003. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature 422, 37–44 10.1038/nature01451 (doi:10.1038/nature01451) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang X, Musyanovych A, Röcker C, Landfester K, Mailänder V, Nienhaus GU. 2011. Specific effects of surface carboxyl groups on anionic polystyrene particles in their interactions with mesenchymal stem cells. Nanoscale 3, 2028–2035 10.1039/c0nr00944j (doi:10.1039/c0nr00944j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. 2006. Determining the size and shape dependence of gold nanoparticle uptake into mammalian cells. Nano Lett. 6, 662–668 10.1021/nl052396o (doi:10.1021/nl052396o) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rejman J, Oberle V, Zuhorn I, Hoekstra D. 2004. Size-dependent internalization of particles via the pathways of clathrin-and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Biochem. J. 377, 159–169 10.1042/BJ20031253 (doi:10.1042/BJ20031253) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labhasetwar V, Song C, Humphrey W, Shebuski R, Levy RJ. 1998. Arterial uptake of biodegradable nanoparticles: effect of surface modifications. J. Pharm. Sci. 87, 1229–1234 10.1021/js980021f (doi:10.1021/js980021f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arbab AS, Bashaw LA, Miller BR, Jordan EK, Lewis BK, Kalish H, Frank JA. 2003. Characterization of biophysical and metabolic properties of cells labeled with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and transfection agent for cellular MR imaging. Radiology 229, 838–846 10.1148/radiol.2293021215 (doi:10.1148/radiol.2293021215) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun XK, Rossin R, Turner JL, Becker ML, Joralemon MJ, Welch MJ, Wooley KJ. 2005. An assessment of the effects of shell cross-linked nanoparticle size, core composition, and surface PEGylation on in vivo biodistribution. Biomacromolecules 6, 2541–2554 10.1021/bm050260e (doi:10.1021/bm050260e) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nativo P, Prior IA, Brust M. 2008. Uptake and intracellular fate of surface-modified gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2, 1639–1644 10.1021/nn800330a (doi:10.1021/nn800330a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holzapfel V, Lorenz M, Weiss CK, Schrezenmeier H, Landfester K, Mailänder V. 2006. Synthesis and biomedical applications of functionalized fluorescent and magnetic dual reporter nanoparticles as obtained in the mini emulsion process. J. Phys. Condensed Matter 18, S2581–S2594 10.1088/0953-8984/18/38/S04 (doi:10.1088/0953-8984/18/38/S04) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Paoli Lacerda SH, Park JJ, Meuse C, Pristinski D, Becker ML, Karim A, Douglas J. 2010. Interaction of gold nanoparticles with common human blood proteins. ACS Nano 4, 365–379 10.1021/nn9011187 (doi:10.1021/nn9011187) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cedervall T, Lynch I, Foy M, Berggård T, Donnelly SC, Cagney G, Linse S, Dawson KA. 2007. Detailed identification of plasma proteins adsorbed on copolymer nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 5754–5756 10.1002/anie.200700465 (doi:10.1002/anie.200700465) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cedervall T, Lynch I, Lindman S, Berggård T, Thulin E, Nilsson H, Dawson KA, Linse S. 2007. Understanding the nanoparticle–protein corona using methods to quantify exchange rates and affinities of proteins for nanoparticles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 2050–2055 10.1073/pnas.0608582104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0608582104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T, Dawson KA. 2008. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for biological impacts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14 265–14 270 10.1073/pnas.0805135105 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0805135105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch I. 2007. Are there generic mechanisms governing interactions between nanoparticles and cells? Random epitope mapping for the outer layer of the protein–material interface. Physica A 373, 511–520 10.1016/j.physa.2006.06.008 (doi:10.1016/j.physa.2006.06.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Röcker C, Pötzl M, Zhang F, Parak WJ, Nienhaus GU. 2009. A quantitative fluoresence study of protein monolayer formation on colloidal nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 577–580 10.1038/nnano.2009.195 (doi:10.1038/nnano.2009.195) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shang L, Brandholt S, Stockmar F, Trouillet V, Bruns M, Nienhaus GU. 2012. Effect of protein adsorption on the fluorescence of ultrasmall gold nanoclusters. Small 8, 661–665 10.1002/smll.201101353 (doi:10.1002/smll.201101353) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shang L, Wang Y, Jiang J, Dong S. 2007. pH-dependent protein conformational changes in albumin:gold nanoparticle bioconjugates: a spectroscopic study. Langmuir 23, 2714–2721 10.1021/la062064e (doi:10.1021/la062064e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebauer JS, Malissek M, Simon S, Knauer SK, Maskos M, Stauber RH, Peukert W, Treuel L. 2012. Impact of the nanoparticle-protein corona on colloidal stability and protein structure. Langmuir 28, 9181–9906 10.1021/la300292r (doi:10.1021/la300292r) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Treuel L, Malissek M, Gebauer JS, Zellner R. 2010. The influence of surface composition of nanoparticles on their interactions with serum albumin. Chem. Phys. Chem. 11, 3093–3099 10.1002/cphc.201000174 (doi:10.1002/cphc.201000174) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Treuel L, Malissek M, Grass S, Diendorf J, Mahl D, Meyer-Zaika W, Epple M. 2012. Quantifying the influence of polymer coatings on the serum albumin corona formation around silver and gold nanoparticles. J. Nanoparticle Res. 14, 1102–1104 10.1007/s11051-012-1102-3 (doi:10.1007/s11051-012-1102-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monopoli MP, Åberg C, Salvati A, Dawson KA. 2012. Biomolecular coronas provide the biological identity of nanosized materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 779–786 10.1038/nnano.2012.207 (doi:10.1038/nnano.2012.207) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pitek AS, O'Connell D, Mahon E, Monopoli MP, Baldelli Bombelli F, Dawson KA. 2012. Transferrin coated nanoparticles: study of the bionano interface in human plasma. PLoS ONE 7, e40685. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040685 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040685) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang T, Bai J, Jiang X, Nienhaus GU. 2012. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles by membrane penetration: a study combining confocal microscopy with FTIR spectroelectrochemistry. ACS Nano 6, 1251–1259 10.1021/nn203892h (doi:10.1021/nn203892h) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothen-Rutishauser BM, Schürch S, Haenni B, Kapp N, Gehr P. 2006. Interaction of fine particles and nanoparticles with red blood cells visualized with advanced microscopic techniques. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 4353–4359 10.1021/es0522635 (doi:10.1021/es0522635) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verma A, Uzun O, Hu Y, Hu Y, Han H-S, Watson N, Chen S, Irvine DJ, Stellacci F. 2008. Surface-structure-regulated cell-membrane penetration by monolayer-protected nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 7, 588–595 10.1038/nmat2202 (doi:10.1038/nmat2202) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Yang S. 2011. Nonspecific adsorption of charged quantum dots on supported zwitterionic lipid bilayers: real-time monitoring by quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation. Langmuir 27, 2528–2535 10.1021/la104449y (doi:10.1021/la104449y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dif A, Henry E, Artzner F, Baudy-Floc'h M, Schmutz M, Dahan M, Marchi-Artzner V. 2008. Interaction between water-soluble peptidic CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals and membranes: formation of hybrid vesicles and condensed lamellar phases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 8289–8296 10.1021/ja711378g (doi:10.1021/ja711378g) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laurencin M, Georgelin T, Malezieux B, Siaugue J-M, Ménager C. 2010. Interactions between giant unilamellar vesicles and charged core-shell magnetic nanoparticles. Langmuir 26, 16 025–16 030 10.1021/la1023746 (doi:10.1021/la1023746) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leroueil PR, Hong S, Mecke A, Baker JR, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM. 2007. Nanoparticle interaction with biological membranes: does nanotechnology present a Janus face? Acc. Chem. Res. 40, 335–342 10.1021/ar600012y (doi:10.1021/ar600012y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roiter Y, Ornatska M, Rammohan AR, Balakrishnan J, Heine DR, Minko S. 2008. Interaction of nanoparticles with lipid membrane. Nano Lett. 8, 941–944 10.1021/nl080080l (doi:10.1021/nl080080l) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leroueil PR, Berry SA, Duthie K, Han G, Rotello VM, McNerny DQ, Baker JR, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM. 2008. Wide varieties of cationic nanoparticles induce defects in supported lipid bilayers. Nano Lett. 8, 420–424 10.1021/nl0722929 (doi:10.1021/nl0722929) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu J, Patel SA, Dickson RM. 2007. In vitro and intracellular production of peptide-encapsulated fluorescent silver nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 2028–2030 10.1002/anie.200604253 (doi:10.1002/anie.200604253) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kostarelos K, et al. 2007. Cellular uptake of functionalized carbon nanotubes is independent of functional group and cell type. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 108–113 10.1038/nnano.2006.209 (doi:10.1038/nnano.2006.209) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho EC, Xie J, Wurm PA, Xia Y. 2009. Understanding the role of surface charges in cellular adsorption versus internalization by selectively removing gold nanoparticles on the cell surface with a I2/KI etchant. Nano Lett. 9, 1080–1084 10.1021/nl803487r (doi:10.1021/nl803487r) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao Y, Sun X, Zhang G, Trewyn BG, Slowing II, Lin VSY. 2011. Interaction of mesoporous silica nanoparticles with human red blood cell membranes: size and surface effects. ACS Nano 5, 1366–1375 10.1021/nn103077k (doi:10.1021/nn103077k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin J, Zhang H, Chen Z, Zheng Y. 2010. Penetration of lipid membranes by gold nanoparticles: insights into cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, and their relationship. ACS Nano 4, 5421–5429 10.1021/nn1010792 (doi:10.1021/nn1010792) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stohs SJ, Bagchi D. 1995. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 18, 321–336 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-H (doi:10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-H) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silver S. 1996. Bacterial resistances to toxic metal ions: a review. Gene 179, 9–19 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00323-X (doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00323-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ratte HT. 1999. Bioaccumulation and toxicity of silver compounds: a review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 18, 89–108 10.1002/etc.5620180112 (doi:10.1002/etc.5620180112) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kittler S, et al. 2010. The influence of proteins on the dispersability and cell-biological activity of silver nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 512–518 10.1039/b914875b (doi:10.1039/b914875b) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kittler S, Greulich C, Diendorf J, Köller M, Epple M. 2010. The toxicity of silver nanoparticles increases during storage due to slow dissolution under release of silver ions. Chem. Mater. 22, 4548–4554 10.1021/cm100023p (doi:10.1021/cm100023p) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Greulich C, Kittler S, Epple M, Muhr G, Köller M. 2009. Studies on the biocompatibility and the interaction of silver nanoparticles with human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 394, 495–502 10.1007/s00423-009-0472-1 (doi:10.1007/s00423-009-0472-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jiang X, Weise S, Hafner M, Röcker C, Zhang F, Parak WJ, Nienhaus GU. 2010. Quantitative analysis of the protein corona on FePt nanoparticles formed by transferrin binding. J. R. Soc. Interface 7, S5–S13 10.1098/rsif.2009.0272.focus (doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0272.focus) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Owens DE, Peppas NA. 2006. Opsonization, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of polymeric nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 307, 93–102 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.010 (doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kah JC, Wong KY, Neoh KG, Song JH, Fu JW, Mhaisalkar S, Olivo M, Sheppard CJ. 2009. Critical parameters in the PEGylation of gold nanoshells for biomedical applications: an in vitro macrophage study. J. Drug Target. 17, 181–193 10.1080/10611860802582442 (doi:10.1080/10611860802582442) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klein J. 2007. Probing the interactions of proteins and nanoparticles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 2029–2030 10.1073/pnas.0611610104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0611610104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maffre P, Nienhaus K, Amin F, Parak WJ, Nienhaus GU. 2011. Characterization of protein adsorption onto FePt nanoparticles using dual-focus fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2, 374–383 10.3762/bjnano.2.43 (doi:10.3762/bjnano.2.43) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frauenfelder H, Nienhaus GU, Johnson JB. 1991. Rate-processes in proteins. Ber. Bunsen Phys. Chem. 95, 272–278 10.1002/bbpc.19910950310 (doi:10.1002/bbpc.19910950310) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nienhaus GU, Heinzl J, Huenges E, Parak F. 1989. Protein crystal dynamics studied by time-resolved analysis of X-ray diffuse scattering. Nature 338, 665–666 10.1038/338665a0 (doi:10.1038/338665a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prapainop K, Witter DP, Wentworth P. 2012. A chemical approach for cell-specific targeting of nanomaterials: small-molecule-initiated misfolding of nanoparticle corona proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4100–4103 10.1021/ja300537u (doi:10.1021/ja300537u) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prapainop K, Wentworth P., Jr 2011. A shotgun proteomic study of the protein corona associated with cholesterol and atheronal-B surface-modified quantum dots. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 77, 353–359 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.12.026 (doi:10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.12.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wentworth P, et al. 2003. Evidence for ozone formation in human atherosclerotic arteries. Science 302, 1053–1056 10.1126/science.1089525 (doi:10.1126/science.1089525) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scheinost JC, Wang H, Boldt GE, Offer J, Wentworth P. 2008. Cholesterol seco-sterol-induced aggregation of methylated amyloid-β peptides: insights into aldehyde-initiated fibrillization of amyloid-β. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3919–3922 10.1002/anie.200705922 (doi:10.1002/anie.200705922) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bieschke J, Zhang Q, Bosco DA, Lerner RA, Powers ET, Wentworth P, Kelly JW. 2006. Small molecule oxidation products trigger disease-associated protein misfolding. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 611–619 10.1021/ar0500766 (doi:10.1021/ar0500766) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nieva J, Shafton A, Altobell LJ, Tripuraneni S, Rogel JK, Wentworth AD, Lerner RA, Wentworth P. 2008. Lipid-derived aldehydes accelerate light chain amyloid and amorphous aggregation. Biochemistry 47, 7695–7705 10.1021/bi800333s (doi:10.1021/bi800333s) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scheinost JC, Witter DP, Boldt GE, Offer J, Wentworth P. 2009. Cholesterol secosterol adduction inhibits the misfolding of a mutant prion protein fragment that induces neurodegeneration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 9469–9472 10.1002/anie.200904524 (doi:10.1002/anie.200904524) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dausend J, Musyanovych A, Dass M, Walther P, Schrezenmeier H, Landfester K, Mailänder V. 2008. Uptake mechanism of oppositely charged fluorescent nanoparticles in HeLa cells. Macromol. Biosci. 8, 1135–1143 10.1002/mabi.200800123 (doi:10.1002/mabi.200800123) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jiang W, Kim BYS, Rutka JT, Chan WCW. 2008. Nanoparticle-mediated cellular response is size-dependent. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 145–150 10.1038/nnano.2008.30 (doi:10.1038/nnano.2008.30) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Storm G, Belliot SO, Daemen T, Lasic DD. 1995. Surface modification of nanoparticles to oppose uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 17, 31–48 10.1016/0169-409X(95)00039-A (doi:10.1016/0169-409X(95)00039-A) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chavanpatil MD, Khdair A, Panyam J. 2006. Nanoparticles for cellular drug delivery: mechanisms and factors influencing delivery. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 6, 2651–2663 10.1166/jnn.2006.443 (doi:10.1166/jnn.2006.443) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim JA, Åberg C, Salvati A, Dawson KA. 2012. Role of cell cycle on the cellular uptake and dilution of nanoparticles in a cell population. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 62–68 10.1038/nnano.2011.191 (doi:10.1038/nnano.2011.191) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T. 2006. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev. Cell 10, 839–850 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002 (doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang L, Rothberg K, Anderson R. 1993. Mis-assembly of clathrin lattices on endosomes reveals a regulatory switch for coated pit formation. J. Cell Biol. 123, 1107–1117 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1107 (doi:10.1083/jcb.123.5.1107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Larkin J, Brown M, Goldstein J, Anderson R. 1983. Depletion of intracellular potassium arrests coated pit formation and receptor-mediated endocytosis in fibroblasts. Cell 33, 273–285 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90356-2 (doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90356-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sandin P, Fitzpatrick LW, Simpson JC, Dawson KA. 2012. High-speed imaging of rab family small GTPases reveals rare events in nanoparticle trafficking in living cells. ACS Nano 6, 1513–1521 10.1021/nn204448x (doi:10.1021/nn204448x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stenmark H. 2009. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 513–525 10.1038/nrm2728 (doi:10.1038/nrm2728) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rink J, Ghigo E, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M. 2005. Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell 122, 735–749 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Feng Y, Press B, Wandinger-Ness A. 1995. Rab 7: an important regulator of late endocytic membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 131, 1435–1452 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1435 (doi:10.1083/jcb.131.6.1435) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vanlandingham PA, Ceresa BP. 2009. Rab7 regulates late endocytic trafficking downstream of multivesicular body biogenesis and cargo sequestration. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12 110–12 124 10.1074/jbc.M809277200 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M809277200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lombardi D, Soldati T, Riederer MA, Goda Y, Zerial M, Pfeffer SR. 1993. Rab9 functions in transport between late endosomes and the trans Golgi network. EMBO J. 12, 677–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ullrich O, Reinsch S, Urbé S, Zerial M, Parton RG. 1996. Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J. Cell Biol. 135, 913–924 10.1083/jcb.135.4.913 (doi:10.1083/jcb.135.4.913) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Simpson JC, Griffiths G, Wessling-Resnick M, Fransen JAM, Bennett H, Jones AT. 2004. A role for the small GTPase Rab21 in the early endocytic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 117, 6297–6311 10.1242/jcs.01560 (doi:10.1242/jcs.01560) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jiang X, Röcker C, Hafner M, Brandholt S, Dörlich RM, Nienhaus GU. 2010. Endo- and exocytosis of zwitterionic quantum dot nanoparticles by live HeLa cells. ACS Nano 4, 6787–6797 10.1021/nn101277w (doi:10.1021/nn101277w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Salvati A, Åberg C, dos Santos T, Varela J, Pinto P, Lynch I, Dawson KA. 2011. Experimental and theoretical comparison of intracellular import of polymeric nanoparticles and small molecules: toward models of uptake kinetics. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 7, 818–826 10.1016/j.nano.2011.03.005 (doi:10.1016/j.nano.2011.03.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lesniak A, Campbell A, Monopoli MP, Lynch I, Salvati A, Dawson KA. 2010. Serum heat inactivation affects protein corona composition and nanoparticle uptake. Biomaterials 31, 9511–9518 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.049 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shapero K, Fenaroli F, Lynch I, Cottell DC, Salvati A, Dawson KA. 2011. Time and space resolved uptake study of silica nanoparticles by human cells. Mol. Biosyst. 7, 371–378 10.1039/c0mb00109k (doi:10.1039/c0mb00109k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gebauer JS, Treuel L. 2011. Influence of individual ionic components on the agglomeration kinetics of silver nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 354, 546–554 10.1016/j.jcis.2010.11.016 (doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2010.11.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cho EC, Zhang Q, Xia Y. 2011. The effect of sedimentation and diffusion on cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 385–391 10.1038/nnano.2011.58 (doi:10.1038/nnano.2011.58) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gao H, Shi W, Freund LB. 2005. Mechanics of receptor-mediated endocytosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9469–9474 10.1073/pnas.0503879102 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0503879102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pitas RE, Friera A, McGuire J, Dejager S. 1992. Further characterization of the acetyl LDL (scavenger) receptor expressed by rabbit smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 12, 1235–1244 10.1161/01.ATV.12.11.1235 (doi:10.1161/01.ATV.12.11.1235) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mühlfeld C, Gehr P, Rothen-Rutishauser B. 2008. Translocation and cellular entering mechanisms of nanoparticles in the respiratory tract. Swiss Med. Wkly. 138, 387–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Geiser M, et al. 2005. Ultrafine particles cross cellular membranes by nonphagocytic mechanisms in lungs and in cultured cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 1555–1560 10.1289/ehp.8006 (doi:10.1289/ehp.8006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Underhill DM, Ozinsky A. 2002. Phagocytosis of microbes: complexity in action. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 825–852 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.103001.114744 (doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.103001.114744) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiang X, Zaitseva E, Schmidt M, Siebert F, Engelhard M, Schlesinger R, Ataka K, Vogel R, Heberle J. 2008. Resolving voltage-dependent structural changes of a membrane photoreceptor by surface-enhanced IR difference spectroscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 12 113–12 117 10.1073/pnas.0802289105 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0802289105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Osawa M. 2001. Surface-enhanced infrared absorption. Top. Appl. Phys. 81, 163–187 10.1007/3-540-44552-8_9 (doi:10.1007/3-540-44552-8_9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Herbig ME, Assi F, Textor M, Merkle HP. 2006. The cell penetrating peptides pVEC and W2-pVEC induce transformation of gel phase domains in phospholipid bilayers without affecting their integrity. Biochemistry 45, 3598–3609 10.1021/bi050923c (doi:10.1021/bi050923c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thorén PEG, Persson D, Isakson P, Goksör M, Önfelt A, Nordén B. 2003. Uptake of analogs of penetratin, Tat(48–60) and oligoarginine in live cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307, 100–107 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01135-5 (doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01135-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Patel L, Zaro J, Shen W-C. 2007. Cell penetrating peptides: intracellular pathways and pharmaceutical perspectives. Pharm. Res. 24, 1977–1992 10.1007/s11095-007-9303-7 (doi:10.1007/s11095-007-9303-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Casals E, Pfaller T, Duschl A, Oostingh GJ, Puntes V. 2010. Time evolution of the nanoparticle protein corona. ACS Nano 4, 3623–3632 10.1021/nn901372t (doi:10.1021/nn901372t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oberdörster G. 2010. Safety assessment for nanotechnology and nanomedicine: concepts of nanotoxicology. J. Intern. Med. 267, 89–105 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02187.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02187.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chithrani BD, Chan WCW. 2007. Elucidating the mechanism of cellular uptake and removal of protein-coated gold nanoparticles of different sizes and shapes. Nano Lett. 7, 1542–1550 10.1021/nl070363y (doi:10.1021/nl070363y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ehrenberg MS, Friedman AE, Finkelstein JN, Oberdörster G, McGrath JL. 2009. The influence of protein adsorption on nanoparticle association with cultured endothelial cells. Biomaterials 30, 603–610 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.050 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.050) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]