Abstract

The identification of undiagnosed disease outbreaks is critical for mobilizing efforts to prevent widespread transmission of novel virulent pathogens. Recent developments in online surveillance systems allow for the rapid communication of the earliest reports of emerging infectious diseases and tracking of their spread. The efficacy of these programs, however, is inhibited by the anecdotal nature of informal reporting and uncertainty of pathogen identity in the early stages of emergence. We developed theory to connect disease outbreaks of known aetiology in a network using an array of properties including symptoms, seasonality and case-fatality ratio. We tested the method with 125 reports of outbreaks of 10 known infectious diseases causing encephalitis in South Asia, and showed that different diseases frequently form distinct clusters within the networks. The approach correctly identified unknown disease outbreaks with an average sensitivity of 76 per cent and specificity of 88 per cent. Outbreaks of some diseases, such as Nipah virus encephalitis, were well identified (sensitivity = 100%, positive predictive values = 80%), whereas others (e.g. Chandipura encephalitis) were more difficult to distinguish. These results suggest that unknown outbreaks in resource-poor settings could be evaluated in real time, potentially leading to more rapid responses and reducing the risk of an outbreak becoming a pandemic.

Keywords: emerging infectious disease, encephalitis, complex networks, South Asia, cluster analysis, early warning systems

1. Introduction

Despite the enormous social, demographic and economic impact of emerging infectious diseases [1], and billions of dollars spent to control them, there has been limited progress in the development of tools for early intervention that could prevent the emergence and spread of pathogens in the initial stages of an epidemic [2–6]. This is an acute problem in resource-poor nations that have limited surveillance capacity and often lack laboratory facilities to diagnose unusual outbreaks.

To address this issue, online databases and surveillance reporting networks have been developed to identify and monitor the emergence and spread of infectious agents. These include tools to aid in the clinical diagnosis of single cases of infectious diseases [7–13], tools that process unverified epidemic intelligence using specific keywords, e.g. HealthMap.org [14,15] and Google Flu Trends [16], those that compile verified outbreak data, e.g. GLEWS (Global Early Warning System for major animal diseases including zoonoses, http://www.glews.net) [17], GAINS (Global Animal INformation System, http://www.gains.org) and Global Infectious Disease and Epidemiology Network (GIDEON) [7] and those that disseminate expert-moderated outbreak reports and anecdotal information, e.g. ProMED-mail [18]. To the best of our knowledge, no decision support tool exists for the rapid and inexpensive assessment of outbreaks, particularly in the face of minimal information and limited resources to make the clinical assessments necessary to parametrize one of the existing diagnostic models.

We developed a method based on network theory to evaluate potential causes of outbreaks of disease. While many statistical approaches exist for assigning multivariate data records into categories, e.g. Bayesian network analysis or discriminant functions analysis [19], the method we present here has the advantage of allowing for multiple equitable solutions for symptom assignment. Our method employs an ensemble of adequate solutions and this ensemble allows one to assess certainty of outbreak diagnosis assignment.

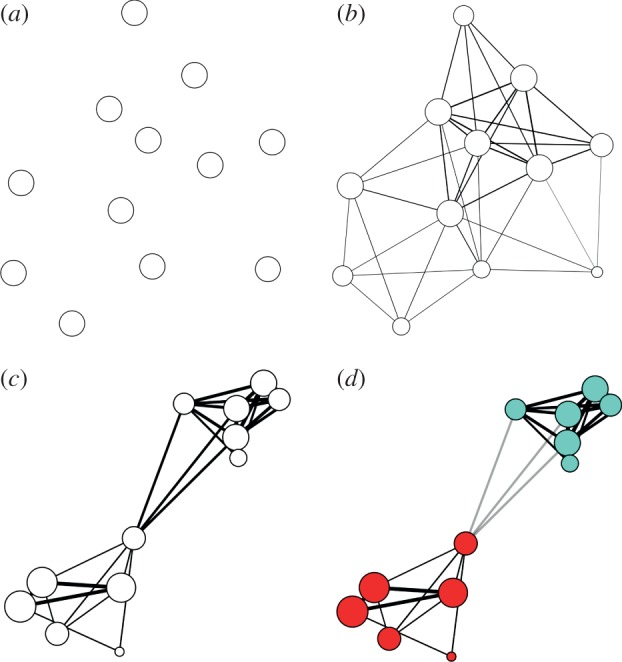

Network theory is the study of relationships between entities (‘nodes’) and connections between these entities (‘edges’) [20]. Network theory has previously been used effectively to describe social and biological datasets [21,22], and it has been shown to be a useful tool for cluster analysis [23]. Here, we consider outbreaks as nodes, and create an edge between any two outbreaks if they share symptoms, or have similar properties such as case-fatality ratio (CFR) or seasonality (figure 1). We give an edge greater weight if the two outbreaks at either end are more similar in that sense (see the electronic supplementary material for details). Groups of outbreaks that are more strongly connected to each other than to other outbreaks in the network can be said to form a ‘cluster’ or, more commonly in network theory, a ‘community’. If outbreaks of different diseases were perfectly distinguishable on the basis of the properties we consider, each disease would form a single and distinct cluster of outbreaks of that disease. In that case, we could use this to link unidentified outbreaks to those of known aetiological agents with similar properties (e.g. seasonality, CFR and symptoms) by adding them to the network and testing which cluster they are most similar to (in the sense that they are strongly connected to outbreaks within that cluster). We applied this method to 125 previously identified outbreak reports of 10 different diseases causing encephalitis in South Asia. We then analysed 97 outbreaks of encephalitis in South Asia reported on ProMED-mail that were reported without a definitive diagnosis. We associated each of them with one of the 10 diseases based on which cluster in the network they are most strongly linked to. As such, our approach uses a novel interpretation of an abstract network to link (unidentified) outbreaks to those of known aetiological agents with similar properties (e.g. seasonality, CFR and symptoms). We chose South Asia as it has been identified as an emerging infectious disease ‘hotspot’ [25] and has a history of recent pathogen emergence, including those causing encephalitis, e.g. Nipah virus (NiV) encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis and cerebral malaria [25]. Furthermore, investigations into encephalitis outbreaks in South Asia have been limited and diagnoses are sometimes controversial [26].

Figure 1.

The method to cluster disease reports of similar properties, here demonstrated using a network consisting of six outbreak reports of bacterial meningitis and six of NiV encephalitis: (a) each outbreak report is associated with a single network node (circle). (b) Edges (lines) between nodes are created if the two reports represented share a symptom or other property. Edges are thicker if more symptoms are shared, and the size of a node represents the total number of symptoms/properties shared with other nodes. Edge length, however, is not significant. (c) Each symptom and outbreak property is then given a weight, and the edge thickness (or edge weight) is now representative of the sum over all the weights of symptoms/properties shared between the two disease reports at the end of the edge. The symptom weights are optimized for greatest clustering of reports. The size of a node now represents the sum over the weights of all edges connected to it, which can be interpreted as the amount of information contained in the report that is relevant for the clustering of reports. (d) An algorithm for community detection finds two clusters: edges that connect two nodes within the same cluster are black, and ones that connect two nodes in two different clusters grey. In this case, the algorithm successfully distinguished between bacterial meningitis (red) and NiV encephalitis (cyan). Note that in all figures, lengths of edges and positions of nodes have no meaning as such, and have been chosen based on an algorithm for optimal visualization [24].

2. Material and methods

2.1. Differential diagnosis of diseases in South Asia

Our aim was to develop a method that could be used to identify the pathogens causing undiagnosed outbreaks of encephalitis in South Asia. We first built a library of potential pathogens, and then developed a model to quantify associations between the symptoms, seasonality and CFR caused by infection with these pathogens.

We used the GIDEON online database to create a library of potential diseases and pathogens and to establish a differential diagnosis for diseases in South Asia with encephalitis as a symptom. The GIDEON database contains a diagnostic module that uses information on symptoms, country, incubation period and laboratory tests to construct a ranked differential diagnosis [27]. Using common characteristics of outbreaks reported in ProMED-mail, we queried GIDEON for the most likely diagnoses for such diseases in each of the eight nations comprising the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC): Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Search criteria included ‘outbreak or case cluster’, ‘severe/fatal’, ‘fever’, ‘neurological/headache’ and ‘neurological/encephalitis’. For each nation, we recorded all potential diagnoses with more than 1 per cent probability of occurrence. Potential diagnoses with less than 1 per cent probability of occurrence and ‘first case scenario’ diagnoses were excluded. The 10 diseases identified and their diagnoses were compiled into an inclusive list of differential diagnoses for the SAARC region. Two diseases, influenza and rabies, appeared in the region-wide differential diagnosis but were excluded from the analysis because symptoms associated with their outbreaks are distinct and relatively easily distinguished from encephalitides (e.g. for rabies, owing to rapid fatality, lack of human-to-human transmission and distinct symptoms). Two other diseases, Chandipura encephalitis and chikungunya fever, were added to the differential diagnosis based on their increasing incidence within the region.

We then conducted a literature search to compile a dataset of the clinical and epidemiological features of each of the 10 diseases (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S1): Chandipura encephalitis, chikungunya fever, dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis, malaria, measles, aseptic meningitis, bacterial meningitis, NiV encephalitis and typhoid/enteric fever. We searched the literature for the clinical and epidemiological features of each disease, and we restricted the results to the SAARC nations in order to capture the seasonality and disease aetiology in this region. For each published report, we recorded the location of the outbreak or study, the month and year of recorded cases, CFR, and the prevalence of symptoms among cases (recorded as percentage of patients). Results for malaria include only complicated and cerebral malaria, and results for ‘dengue’ include dengue fever, dengue haemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome.

2.2. Network analysis

We developed a network model to determine how outbreaks of the same disease cluster together and how distinct they are compared with outbreaks of other diseases, with respect to seasonality, CFR and symptoms. Our method is based on the assumption that in outbreaks of the same disease patients will show similar symptoms, occur in similar times of the years, and/or have similar CFRs. If this assumption is correct, outbreaks will be linked by similar traits and would be clustered into groups of the same disease (figure 1) [28]. We constructed a network from the set of 125 diagnosed outbreak reports from the literature of the 10 diseases selected, with each node representing a single outbreak report. A connection (edge) is created between two outbreaks (nodes) if they share a symptom or property, with the weight of the edge given by a weighted sum of all symptoms/properties shared. We used a previously developed algorithm to detect densely connected clusters of outbreaks in networks [29]. Because some symptoms may be more important than others in distinguishing one disease from another, we allowed for unequal weights to each of the symptoms in the model. We determined appropriate symptom weights using a method that yields maximal within-cluster similarity and between-cluster dissimilarity (called network modularity, see electronic supplementary material, appendix methods and table S2). Because multiple sets of symptom weights could result in similar maximal network modularity, we created an ensemble of sample networks, each with its own set of symptom/property weights and averaged over all of them in evaluating the outbreak reports to increase the reliability of our analysis.

2.3. Model testing

We tested the reliability of our method by removing each of the reference reports from the network, running the model with the removed reference report as an ‘undiagnosed’ report, and checking if the model-predicted diagnosis matched the actual diagnosis. This allowed us to determine the sensitivity (proportion of true positives correctly identified as such) and specificity (proportion of true negatives correctly identified as such) of the model for each disease. We calculated positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) for each of the 10 diseases. PPV is the proportion of positive results that are true positives (e.g. the proportion of outbreaks identified by the model as dengue that were laboratory confirmed as dengue cases), whereas NPV is the proportion of negative results that are true negatives (e.g. the proportion of outbreaks identified by the model as not dengue and were confirmed as something else). We assumed that each of the 10 diseases considered was equally likely to be the correct diagnosis for any given ‘mystery case’ presented, and that all of our reports could be diagnosed as one of the 10 diseases considered.

2.4. Undiagnosed outbreaks

We searched ProMED-mail for reports of undiagnosed encephalitis between 1994 and 2008. Search terms included ‘encephalitis’, ‘fever’, ‘mystery’, ‘undiagnosed’ and ‘unknown origin’. Search results were again restricted to the SAARC nations. For each ProMED-mail report, the geographic location, month and year of the first recognized case, number of people affected, number of deaths and clinical symptoms were recorded. We calculated the CFR as the number of deaths per total number of cases reported for each outbreak. For outbreaks with multiple associated incident reports over time, we recorded the total number of reports and final diagnosis, if provided.

For the period under study (1994–2008), a sample of 99 outbreaks of undiagnosed encephalitis was selected from ProMED-mail (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S3). We removed two outbreak reports that had incomplete information (lacking symptoms, CFR or seasonality), reducing the dataset to 97 outbreaks. We added the undiagnosed outbreaks to each of the sample networks, using the weights as determined before. For each undiagnosed outbreak added, we determined the cluster the outbreak associated best with (see the electronic supplementary material), and recorded each disease present in that cluster. We used a bootstrap method across the sample networks to identify the disease associated most frequently with a given undiagnosed outbreak, and we consider this as its primary diagnosis. We calculated the number of times a disease was associated with a given outbreak out of the total number of networks tested to determine an association score and a corresponding 95% CI around this association. When multiple diseases had overlapping percent association CIs, they were all considered to be plausible diagnoses (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S4), thus increasing sensitivity but reducing specificity of our method.

3. Results

Seven communities or clusters of outbreaks were identified based on symptoms, seasonality and CFR from associations of the original set of 125 outbreak reports from the literature of the 10 diseases tested (figure 2, outer ring). Ideally, each cluster of outbreaks would consist of reports of a single disease. However, given overlapping sets of symptoms, CFR or seasonality, most clusters included outbreaks of more than one disease. Of the 10 diseases included in this study, NiV infection was identified most reliably (100% sensitivity (table 1) and 80% PPV (table 2)), and forms a distinct cluster (figure 2). It was unique in our analysis in having a high CFR (approx. 70%), a distinct seasonality (spring) and symptoms of respiratory difficulty, seizure, unconsciousness, vomiting and weakness. Other diseases with relatively high PPV were chikungunya fever (75% PPV) on the basis of low CFR and symptoms of nausea, joint pain, rash and myalgia, and typhoid fever (58% PPV) based on the symptom of pneumonia and low CFR (a few percent). Diseases that were moderately difficult to identify were malaria (47% PPV) on the basis of CFR (approx. 30%) and the symptoms of unconsciousness, jaundice, acute renal failure, seizure, respiratory difficulty and neck rigidity; and bacterial meningitis (PPV 42%) on the basis of CFR (approx. 15%) and neck rigidity. The diseases most difficult to identify were dengue fever (31% PPV), Chandipura encephalitis (27% PPV), Japanese encephalitis (25% PPV) and measles (21% PPV), all of which had properties that made them similar to other diseases. As the reference dataset contained only three entries of aseptic meningitis, the PPV of 49 per cent is tentative.

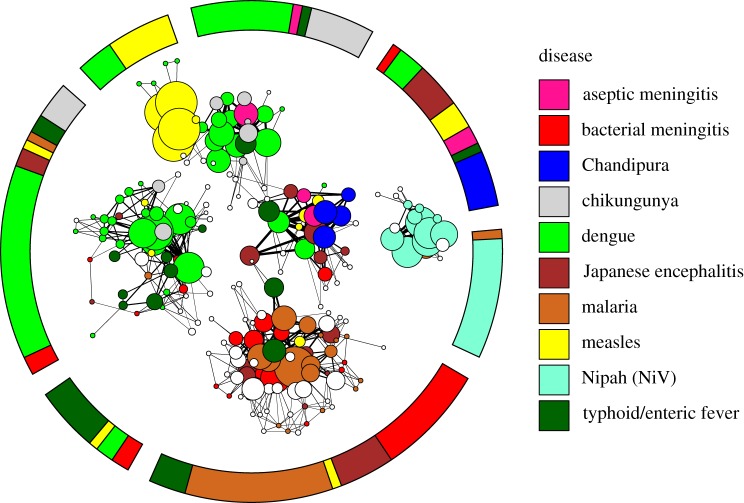

Figure 2.

Visualization of the network of diagnosed outbreaks of diseases with the potential to cause encephalitis (coloured) and outbreaks of undiagnosed encephalitis (white). The inner network describes the strength and relationship of individual outbreaks to each other, while the outer ring gives the composition of the seven communities of disease that are found by the community detection algorithm. Outbreaks of the same disease (colour) tend to cluster together. The network model acts to minimize the number of edges between outbreaks in different communities of disease and maximize the number of edges between outbreaks within a single community of disease. Each circle, called a ‘node’, represents a single outbreak report. Lines connecting two nodes indicate shared traits between two outbreak reports, in symptoms reported, the CFR or seasonality. Lines connecting two outbreaks within a single community are black, and lines between two outbreaks in different communities are in grey. Thicker lines represent a greater number of shared traits and thinner lines indicate fewer shared traits. Where nodes overlap, they are strongly connected. The size of a node (circle) representing an outbreak is proportional to the sum over the thicknesses of all edges connected to it, which can be interpreted as the amount of information contained in the outbreak report. Note that in all figures, lengths of edges and positions of nodes have no meaning as such, and have been chosen based on an algorithm for optimal visualization [24].

Table 1.

The sensitivity and specificity for every disease pair using the outbreak assessment model. The values on the diagonal (values in italic) give the sensitivity, that is, the proportion of actual positive diagnoses that are correctly identified as such. The off-diagonal values (the other values) give the specificity for each disease pair, that is, the proportion of actual negatives that are correctly identified as such.

| aseptic meningitis | bacterial meningitis | Chandipura encephalitis | chikungunya fever | dengue | Japanese encephalitis | malaria | measles | NiV encephalitis | typhoid fever | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aseptic meningitis | 0.33 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| bacterial meningitis | 1 | 0.53 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.91 |

| Chandipura encephalitis | 1 | 0.94 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 0.92 | 1 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.91 |

| chikungunya fever | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.86 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 0.91 | 1 | 1 |

| dengue | 0.67 | 0.88 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.91 |

| Japanese encephalitis | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 1 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.91 |

| malaria | 1 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.86 | 1 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 1 | 1 |

| measles | 0.33 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.8 | 0.77 | 1 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.82 |

| NiV encephalitis | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| typhoid fever | 1 | 0.82 | 1 | 1 | 0.95 | 1 | 1 | 0.64 | 1 | 0.82 |

Table 2.

Positive and NPV for every disease pair using the outbreak assessment model. PPV on the diagonal (values in italic) give the proportion of actual model-predicted positive diagnoses that are true positives. NPV on the off-diagonals (the other values) give the proportion of negative model predictions that are true negative diagnoses.

| aseptic meningitis | bacterial meningitis | Chandipura encephalitis | chikungunya fever | dengue | Japanese encephalitis | malaria | measles | NiV encephalitis | typhoid fever | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aseptic meningitis | 0.49 | 1 | 0.63 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| bacterial meningitis | 1 | 0.42 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 1 | 0.93 |

| Chandipura encephalitis | 1 | 0.94 | 0.27 | 1 | 1 | 0.92 | 1 | 1 | 0.51 | 0.90 |

| chikungunya fever | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 1 | 1 | 0.92 | 1 | 1 |

| dengue | 0.89 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.72 | 0.31 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 1 | 0.97 |

| Japanese encephalitis | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.84 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.96 |

| malaria | 1 | 0.73 | 1 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.90 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 1 | 1 |

| measles | 0.5 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.21 | 1 | 0.93 |

| NiV encephalitis | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 |

| typhoid fever | 1 | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 0.97 | 1 | 1 | 0.74 | 1 | 0.58 |

Of the 97 unidentified outbreaks from ProMED that we analysed, our model evaluated 27 as uniquely associated with a single disease (figure 2, white circles of the inner network; electronic supplementary material, appendix table S4). A further 38 diseases were associated with two diseases and 16 were associated with three of the 10 diseases. Of these 54 that yielded multiple diagnoses, six were associated with NiV. Sixteen outbreaks were marked as inconclusive because they either did not contain enough information or associated with more than three diseases.

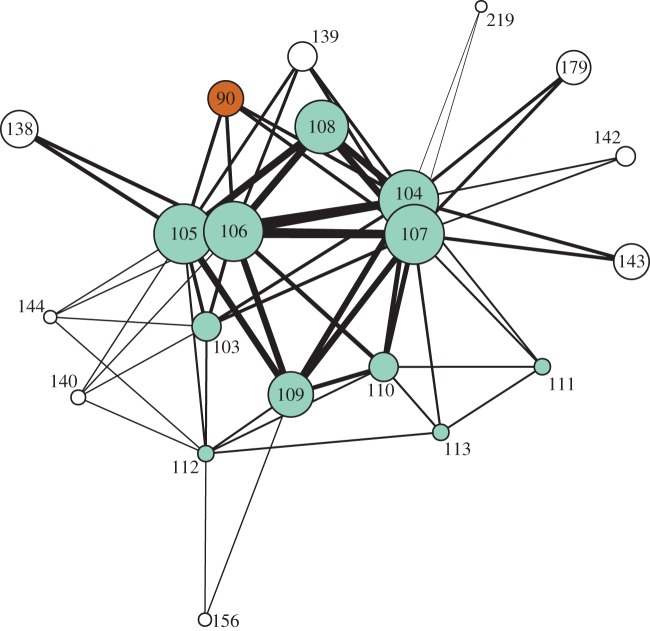

Since NiV was the best-identified disease in our dataset (PPV 80%) and is relatively new and therefore easily misidentified on the ground, we investigated further the possible outbreaks of NiV (figure 3). Of the six associated with NiV in our model, two were clinically confirmed as NiV in follow-up studies. For the other four, two were never identified, one was diagnosed as dengue (but moderators speculated that it may have been NiV), and one was diagnosed as avian influenza, which was not represented in our reference dataset.

Figure 3.

Zoomed in visualization of diagnosed (coloured circles) and undiagnosed outbreaks (white circles) in the Nipah cluster (figure 2). Outbreaks are given by ID number (electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S3), with outbreaks of NiV encephalitis in cyan and malaria in rust, with undiagnosed outbreaks in white, as in figure 2.

Attempts to identify two unknown outbreaks highlight the importance of accurate data in the initial reports. Our model associated two other outbreaks that were later reported in the literature to have been diagnosed as NiV with malaria, bacterial meningitis, Japanese encephalitis or typhoid fever [30,31]. This misidentification resulted from the fact that in the initial ProMED-mail reports for these two outbreaks, the CFR was significantly lower than in the post-outbreak data in the literature [30,31]. The CFR may have been understated in ProMED-mail reports due to incomplete recording or right-censoring of the CFR when estimated during an ongoing outbreak [32]. When the later estimates for CFR from the literature were used for these two outbreaks, our method correctly identified them as NiV.

4. Discussion

We developed a novel method to identify disease outbreaks based on their similarity in properties and symptoms reported. Our method yielded high PPV, sensitivity and specificity for an important virulent disease, NiV, and relatively high values for several other causes of encephalitis in South Asia. We then used this method on unidentified reports of encephalitis outbreaks in South Asia, and identified several outbreaks as likely being caused by NiV, which was new to the region at the time when the outbreaks occurred. Retrospective studies of several of the NiV outbreaks identified the causative agent, and our method provided the correct identification in most cases, but with a key caveat: when the original outbreak contained inaccurate information on one or more outbreak traits (in this case, the CFR), the method incorrectly classified the outbreaks. This highlights the strength of the method when the original outbreak has accurate information, as well as the importance of the quality of information in the reporting system. Unfortunately, inaccurate initial estimates of the CFR are not infrequent (and difficult to correct if they result from right-censoring) and can lead to allocations of public health resources that might retrospectively be considered less than ideal, e.g. the 2009 H1N1 pandemic [33–35].

Although there are limitations to our approach, this study provides a proof of principle for a potentially powerful method. As just noted, the accuracy of our method relies critically on the accuracy of the data reported and the completeness of the reports. Furthermore, it is possible that some outbreaks continued beyond the last posting of details on ProMED-mail, and CFRs estimated during an outbreak are known to be biased [32]. Some of these problems could be mitigated by including data taken at different stages of outbreaks or by comparing the unidentified outbreak reports with identified outbreaks reported via the same source (ProMED-mail). In addition, even with accurate information, our method can only provide probabilities for association with each of the diseases based on the assumption that it is one of the diseases. However, while our method is currently limited by the list of reference diseases provided, it can also be used to flag reports that do not seem to fit any of these well. If, for example, several outbreak reports for a region were highly clustered with each other but not with any known disease in the model, then this would be evidence for a potentially new disease or new disease to the region, and could be prioritized for further investigation. Similarly, this approach may have value in determining whether exotic pathogens have been introduced to a region either inadvertently or deliberately. The ensuing outbreaks may have characteristics that cause them to cluster with diseases outside those normally encountered in a region, and an expanded network analysis may be able to identify their aetiology more rapidly than sample collection would allow.

This method can be applied more broadly to extend the range of diseases as well as hosts under consideration (e.g. zoonotic disease in wildlife reservoir hosts). Disease communities with distinct symptoms will be the best candidates for use with this method. Encephalitis was an ideal candidate symptom as it was less common than a symptom such as fever, but common enough to be shared by a set of diseases within a single region. Diseases with respiratory illness, on the other hand, would be significantly more difficult to differentiate because of the ubiquitous nature of this symptom across many possible diseases. Further research is required to determine the full potential of this approach and the applicability of this method to other diseases.

A major strength of our approach is that it does not require expert judgement or laboratory analysis and provides a way to quickly and inexpensively assess outbreaks. A key direction for future research would be to compare the approach we have proposed here to expert opinion. Comparisons of our method to other clustering techniques would also be of substantial interest, but we note that an important challenge is that many other methods have substantial difficulty with incomplete data and unequal weighting of traits, whereas our method is able to overcome both of these obstacles. Given the opportunistic nature of outbreak reports, this is an important strength.

Our method has the potential to greatly increase the value of surveillance systems such as ProMED-mail, and online surveillance systems in general, which rapidly disseminate information on outbreaks prior to the results of laboratory diagnostics. Although our initial analysis was restricted to ProMED-mail, it is likely that this method would also be effective using data that have been collected by filtered searches such as those used by HealthMap [15]. More generally, the recent increase in the number of online surveillance tools, and their speed and efficiency at reporting novel outbreaks, combined with our analysis approach, could become a significant rapid identification tool for diagnosis.

With increasing availability and capacity of Internet surveillance systems, our application of network theory to outbreak assessment demonstrates the inherent, and underestimated value in collecting key data on novel outbreaks, and disseminating it early and openly. There is immense potential in using methods for automatic text recognition combined with improvements to our method and integration with alternative methods for cluster analysis, to extract as much information as possible from these reports. Many new infections such as NiV first emerge in resource-poor regions, making an intensive and/or active surveillance system difficult. With relatively little additional development, the method presented here could provide a low-cost tool that allows for the rapid, objective assessment of outbreaks of diseases at the onset of their emergence.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government. This work was also supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Science Foundation (NSF) ‘Ecology of Infectious Diseases’ awards from the John E. Fogarty International Center (2R01-TW005869), the NSF (EF-0914866), DTRA (HDTRA1-13-C-0029), the Rockefeller Foundation, the New York Community Trust, the Eppley Foundation for Research, Google.org, the NIH (1R01AI090159-01) and a NSF Human and Social Dynamics ‘Agents of Change’ award (BCS—0826779 & BCS-0826840). T.L.B. acknowledges the Research and Policy for Infectious Disease Dynamics program of the Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the Fogarty International Center, NIH for funding. S.F. acknowledges the EU FP7 funded integrated project EPIWORK (grant agreement no. 231807) for funding. The authors thank J. Bryden, L. Madoff, N. Wale, J. White and J. Zelner for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Morse SS. 1995. Factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1, 7–15 10.3201/eid0101.950102 (doi:10.3201/eid0101.950102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe ND, Daszak P, Kilpatrick AM, Burke DS. 2005. Bushmeat hunting, deforestation and prediction of zoonotic emergence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 1822–1827 10.3201/eid1112.040789 (doi:10.3201/eid1112.040789) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson NM, Cummings DAT, Cauchemez S, Fraser C, Riley S, Meeyai A, Iamsirithaworn S, Burke DS. 2005. Strategies for containing an emerging influenza pandemic in Southeast Asia. Nature 437, 209–214 10.1038/nature04017 (doi:10.1038/nature04017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss RA, McMichael AJ. 2004. Social and environmental risk factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Nat. Med. 10, S70–S76 10.1038/nm1150 (doi:10.1038/nm1150) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hufnagel L, Brockmann D, Geisel T. 2004. Forecast and control of epidemics in a globalized world. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15 124–15 129 10.1073/pnas.0308344101 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0308344101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogich TL, Chunara R, Scales D, Chan E, Pinheiro LC, Chmura AA, Carroll D, Daszak P, Brownstein JS. 2012. Preventing pandemics via international development: a systems approach. PLoS Med. 9, e1001354. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001354 (doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001354) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felitti VJ. 2002. GIDEON: global infectious disease and epidemiology network. JAMA 287, 2433–2434 10.1001/jama.287.18.2433 (doi:10.1001/jama.287.18.2433) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graber M, Mathew A. 2008. Performance of a web-based clinical diagnosis support system for internists. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 37–40 10.1007/s11606-007-0271-8 (doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0271-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller RA. 2009. Computer-assisted diagnostic decision support: history, challenges, and possible paths forward. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 14, 89–106 10.1007/s10459-009-9186-y (doi:10.1007/s10459-009-9186-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shortliffe EH. 1987. Computer-programs to support clinical decision-making. JAMA 258, 61–66 10.1001/jama.1987.03400010065029 (doi:10.1001/jama.1987.03400010065029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berner ES, et al. 1994. Performance of four computer-based diagnostic systems. N. Engl. J. Med. 330, 1792–1796 10.1056/NEJM199406233302506 (doi:10.1056/NEJM199406233302506) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warner HR, Toronto AF, Veasey LG, Stephenson R. 1961. A mathematical approach to medical diagnosis. JAMA 177, 177–183 10.1001/jama.1961.03040290005002 (doi:10.1001/jama.1961.03040290005002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnett GO, Cimino JJ, Hupp JA, Hoffer EP. 1987. DXPLAIN —an evolving diagnostic decision-support system. JAMA 258, 67–74 10.1001/jama.1987.03400010071030 (doi:10.1001/jama.1987.03400010071030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brownstein JS, Freifeld CC, Chan EH, Keller M, Sonricker AL, Mekaru SR, Buckeridge DL. 2010. Information technology and global surveillance of cases of 2009 H1N1 influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1731–1735 10.1056/NEJMsr1002707 (doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1002707) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brownstein JS, Freifeld CC, Madoff LC. 2009. Digital disease detection—harnessing the web for public health surveillance. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 2153–2157 10.1056/NEJMp0900702 (doi:10.1056/NEJMp0900702) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrad C. 2010. Google flu trends: mapping influenza in near real time. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 14, e185. 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.02.1899 (doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2010.02.1899) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FAO, OIE, WHO 2011. GLEWS: global early warning and response system for major animal diseases, including zoonoses. See http://www.glews.net/ (accessed 5 January 2011).

- 18.Madoff LC, Woodall JP. 2005. The Internet and the global monitoring of emerging diseases: lessons from the first 10 years of ProMED-mail. Arch. Med. Res. 36, 724–730 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.06.005 (doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.06.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Everitt BS, Landau S, Leese M. 2009. Cluster analysis, 4th edn Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman MEJ. 2010. Networks: an introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasserman S, Faust K. 1994. Social network analysis: methods and applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazer D, et al. 2009. Computational social science. Science 323, 721–723 10.1126/science.1167742 (doi:10.1126/science.1167742) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Granell C, Gomez S, Arena A. 2011. Unsupervised clustering analysis: a multiscale complex networks approach. See http://arxiv.org/abs/11011890v1 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fruchterman TMJ, Reingold EM. 1991. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw. Pract. Exp. 21, 1129–1164 10.1002/spe.4380211102 (doi:10.1002/spe.4380211102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones KE, Patel N, Levy M, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, Daszak P. 2008. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–994 10.1038/nature06536 (doi:10.1038/nature06536) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S. 2003. Inadequate research facilities fail to tackle mystery disease. Br. Med. J. 326, 12. 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.12/d (doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7379.12/d) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edberg SC. 2005. Global infectious diseases and epidemiology network (GIDEON): a worldwide web-based program for diagnosis and Informatics in infectious diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 123–126 10.1086/426549 (doi:10.1086/426549) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryden J, Funk S, Geard N, Bullock S, Jansen VAA. 2011. Stability in flux: community structure in dynamic networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 8, 1031–1040 10.1098/rsif.2010.0524 (doi:10.1098/rsif.2010.0524) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blondel VD, Guillaume JL, Lambiotte R, Lefebvre E. 2008. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. P10008. 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008 (doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hossain MJ, et al. 2008. Clinical presentation of Nipah virus infection in Bangladesh. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46, 977–984 10.1086/529147 (doi:10.1086/529147) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu VP, et al. 2004. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 2082–2087 10.3201/eid1012.040701 (doi:10.3201/eid1012.040701) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghani AC, et al. 2005. Methods for estimating the case fatality ratio for a novel, emerging infectious disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 162, 479–486 10.1093/aje/kwi230 (doi:10.1093/aje/kwi230) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bautista E, et al. 2010. Medical progress: clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1708–1719 10.1056/NEJMra1000449 (doi:10.1056/NEJMra1000449) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson N, Baker MG. 2009. The emerging influenza pandemic: estimating the case fatality ratio. Eurosurveillance 14, 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fraser C, et al. 2009. Pandemic potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): early findings. Science 324, 1557–1561 10.1126/science.1176062 (doi:10.1126/science.1176062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]