Abstract

Objectives

This study tested the hypothesis that monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1) is required for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and smooth muscle phenotypic modulation in a mouse elastase perfusion model.

Methods

Infrarenal aortas of C57BL/6 (wild type [WT]) and MCP1 knockout (KO) mice were analyzed at 14 days after perfusion. Key cellular sources of MCP1 were identified using bone marrow transplantation. Cultured aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs) were treated with MCP1 to assess its potential to directly regulate SMC contractile protein expression and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).

Results

Elastase perfused WT aortas had a mean dilation of 102% (n = 9) versus 53.7% for MCP1KO aortas (n = 9, P < .0001) and 56.3% for WT saline-perfused controls (n = 8). Cells positive for MMP9 and Mac-2 were nearly absent in the KO aortas. Complimentarily, the media of the KO vessels had abundant differentiated smooth muscle and intact elastic fibers and markedly less MMP2. Experiments in cultured SMCs showed MCP1 can directly repress smooth muscle markers and induce MMP2 and MMP9. Bone marrow transplantation studies showed that KO of MCP1 in bone marrow–derived cells protects from AAA formation. Moreover, KO in the bone was significantly more protective than global KO, suggesting an unexpected benefit to selectively depleting MCP1 in bone marrow–derived cells.

Conclusions

These results have shown that MCP1 derived from bone marrow cells is required for experimental AAA formation and that retention of nonbone marrow MCP1 limits AAA compared with global depletion. This protein contributes to macrophage infiltration into the AAA and can act directly on SMCs to reduce contractile proteins and induce MMPs.

The etiology of aortic aneurysms (AAs) is thought to be a complex interplay among the vessel wall, innate immune cells, and the adaptive immune system.1 The predominant histologic hallmarks of AAs include the presence of an abundant inflammatory infiltrate and the upregulation of proteases, including matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)2 and MMP9.1 These enzymes play an essential role in AA by destruction of collagen and elastin, thereby weakening the vessel wall. Bone marrow–derived cells are the required source of MMP9 and nonbone marrow–derived cells are the essential contributor of MMP2, indicating that both are active participants in AA pathogenesis.2–4

Our laboratory has recently shown that phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs), as defined by coordinate downregulation of multiple SMC-selective contractile proteins, occurs within experimental abdominal AAs (AAAs).5 This is complimented by human genetic studies suggesting genetic defects in SMC contractile proteins underlie thoracic aortic aneurysms.6 Although contractile proteins are key to anchoring cells to matrix, the exact mechanisms whereby their genetic defect or transcriptional downregulation leads to an AA has not been definitively identified. Nevertheless, data strongly suggest the importance of proper SMC contractile protein expression.

Evidence from other vascular diseases suggests that macrophages and other circulating cells are important sources of ligands capable of altering contractile protein expression.7–11 In contrast, the SMC is becoming increasingly recognized as an important contributor to the inflammatory milieu.12 There is therefore evidence to suggest that leukocyte infiltration and SMC phenotypic modulation within AAAs might be interrelated and, potentially, interdependent processes key to AAA formation.

Although this interplay between SMC phenotypic changes and macrophage recruitment is likely complex, evidence suggests C-C chemokine monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1) might regulate both leukocyte recruitment and the SMC phenotype. Its interaction with CCR2, a G-protein coupled receptor whose ligands include MCP1, MCP3, and MCP5, has been shown to be essential for the recruitment of monocytes in response to various pathogens.13,14 Interestingly, MCP1 has been shown to directly promote SMC migration15 and to induce tissue factor, 16 even in the genetic absence of CCR2. Taken together, this suggests MCP1 might be a crucial determinant of AAA macrophage and SMC content and, therefore, might play a major role in disease progression.

Although there has not been a direct study of MCP1 in AAAs, seemingly controversial results have been obtained from investigations into the role of CCR2. Specifically, in experimental models, knockout of CCR2,17 leukocyte targeted knockout by way of bone marrow transplant,18 and small interfering RNA knockdown of CCR2 in leukocytes,19 all significantly inhibit AAAs. However, depleting CCR2’s ligands using dominant negative CCR2 resulted in an apparent increase in aortic diameter.19 Given these apparently conflicting results, compounded by the existence of multiple ligands for CCR2 and the ability of MCP1 to act in CCR2’s genetic absence,16 there is a clear need to definitively address the role of MCP1 in AAAs. We aimed to resolve this deficiency using genetic knockout and delineate the cellular source of MCP1 in AAA using bone marrow transplantation.

METHODS

Elastase Perfusion Model of Aneurysm Formation

C57BL/6 and MCP1KO mice13 were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Me). All KOs were on a C57BL/6 background. The AAA model used has been described previously.5,20 In brief, the procedure includes in situ isolation of the abdominal aorta, cannulation, and perfusion of 0.47 U/mL porcine pancreatic elastase (Sigma-Aldritch, St. Louis, Mo) for 5.5 minutes. Control wild type (WT) mice were perfused with 0.9% normal saline. AAAs develop reproducibly 14 days after elastase perfusion in the WT mice and none developed in the saline-perfused controls. All procedures were performed with the surgeon unaware of the identity of the mice using an elastase solution prepared from Sigma lot no. 078K7018. All animal procedures were in accordance with University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee Protocol 3634.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

The extracted aortas were paraffin embedded and cut into 5-µm sections. In brief, after antigen retrieval (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif) with a pressure cooker, the primary antibodies were bound and detected using the VectaStain Elite Kit. The antibodies used were MMP9 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn), smooth muscle α-actin (SMαA) (Dako, Carpentaria, Calif), MCP1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif), and Mac-2 (Cedarlane Laboratories, Burlington, NC). Visualization was done with diaminobenzidine (Dako) for MMP9, MCP1, and Mac-2, and Cy-3 (Sigma Aldrich) for SMαA. Counter staining was done using Harris Hematoxylin 1 (Richard-Allen Scientific, Kalamazoo, Mich). Negative controls were run with the primary antibody omitted. Histochemistry was performed using a modified Russel-Movat pentachrome method to visualize the elastic fibers. Images were acquired using the 10× objectives on a Zeiss microscope equipped with an AxioCam digital camera using the AxioCam, version 4.6, software program.

Smooth Muscle Culture and Reagents

Rat aortic SMCs were cultured as previously described.21 The cells were grown to confluence and serum starved for 3 days before treatment with MCP1 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 24 hours. RNA was harvested using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif), and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) performed to quantify SmαA, SM22a, and SM-MHC mRNA, as described previously.10 The primers used to detect MMP2 were 5′-catcgctgcaccatcgcccatcatc and 5′-cccagggtccacagctcatcat catcaa and those for MMP9 were 5′-agctgactacgacacagacagaa and 5′-ggccctcgaagatgaatggaaat.

Bone Marrow Transplantation

Six-week-old WT (n = 9) and MCP1KO mice (n = 6) were sublethally irradiated with 2 separate exposures of 650 mCu radiation 3 hours apart. Bone marrow was extracted from the femur and tibia of 2 WT and 2 MCP1KO mice by flushing with sterile Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline; 2 × 106 cells were injected into the tail vein of the irradiated hosts immediately after the second irradiation. The mice were allowed to recover for 6 weeks before elastase perfusion. Depletion of the host bone marrow by irradiation was documented by not injecting cells into the irradiated mice of both genotypes and observing lethality. The identity of the mice before reconstitution was confirmed using qPCR genotyping protocols (available from: jaxmice.jax.org) for the MCP1KO transgene. All mice were killed 14 days after elastase perfusion, and the aortas were processed for histologic examination. The peripheral blood cells and peripheral aortic tissue were isolated after bone marrow transfer and analyzed using qPCR to confirm successful and complete reconstitution.

Human Tissue Collection

Human AAA tissue was collected according to the University of Virginia institutional review board protocol 13178. All patients provided preoperative consent. AAA tissue was resected at open surgical AAA repair, and tissue was obtained from the ascending aorta by aortic punch from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting as a control. The harvested tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, processed, and embedded in paraffin. The control tissue was collected only from patients without a history of collagen vascular disease or aneurysms and without evidence of atherosclerosis in the ascending aorta.

RESULTS

MCP1 Increased in Mouse and Human AAAs

To confirm MCP1’s presence in AAAs, we first analyzed WT mouse aortas 14 days after elastase or saline perfusion. MCP1 was markedly elevated by immunohistochemistry 14 days after elastase perfusion compared with the age-matched, saline-perfused control aortas (Figure 1, A). Similarly, MCP1 protein was significantly more abundant in the aortas from patients undergoing open aneurysm repair than in the nonaneurysmal control aortas (Figure 1, B). These data confirm previous reports of increased MCP1 production in human22 and mouse23 AAAs and highlight the potential importance of MCP1 in experimental and human AAAs.

FIGURE 1.

Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1) is increased in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and required for disease progression. A, Immunohistochemistry performed 14 days after surgery indicates MCP1 is upregulated in elastase-perfused AAAs compared with saline-perfused controls. B, MCP1 more abundant in tissue from patients undergoing open aneurysm repair than in control aorta from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Wild type (WT) aortas perfused with elastase (black squares) show significantly greater change in aortic diameter than MCP1KO aortas perfused with elastase (black triangles) at 14 days (P < .0001). C, MCP1KO aortas statistically indistinguishable from WT aortas perfused with saline (black diamonds).

MCP1KO Mice Resistant to Experimental AAA

MCP1KO mice were obtained on a C57Bl/6 background from the Jackson Laboratory.13 The baseline aortic diameters were equivalent for WT and MCP1KO mice, and no overt signs of developmental vascular differences were present. The MCP1KO mice subjected to elastase perfusion did not form aneurysms and exhibited a mean aortic dilation of 53.7%, a significant reduction compared with the 102% increase in the age-matched WT mice after elastase perfusion (P < .0001). Moreover, the mean dilation of the MCP1KO mice was similar to the 56.3% observed in the saline-perfused WT mice (Figure 1, C). It is important to note that the dilation seen in the saline controls, which was related to the mechanical disruption during perfusion, was similar to that seen in previous studies.5 These results indicate that MCP1 is required for AAA formation after elastase perfusion.

MCP1KO Mice Exhibited Near Absence of Mac2 or MMP9-Positive Cells After Elastase Perfusion

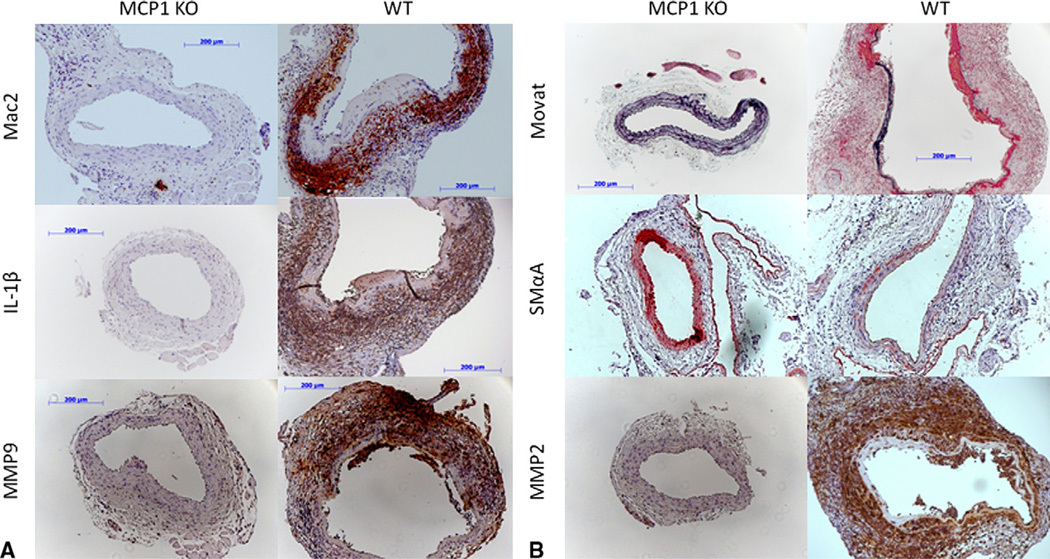

Given the role of MCP1 in monocyte chemotaxis, we hypothesized one mechanism by which MCP1KO prevents AAA formation would be through inhibiting macrophage infiltration. The results of the immunohistochemistry analyses 14 days after elastase perfusion showed markedly reduced expression of Mac-2, a macrophage surface maker, in the elastase-perfused MCP1KO mice. This is in stark contrast to the WT mice, in which Mac-2 staining was abundant within the medial and adventitial layers of the vessel. Furthermore, levels of the potent, pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β) was markedly reduced in the vessel wall of the MCP1KO mice (Figure 2, A). Thus, it appears MCP1 signaling contributes to monocyte recruitment and IL-1β production 14 days after elastase perfusion.

FIGURE 2.

MCP1KO reduces inflammation and protects from medial degredation. Immunohistochemistry performed 14 days after elastase perfusion indicated levels of Mac-2, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)9 are significantly reduced in MCP1KO aortas (left column) compared with WT aortas (right column) 14 days after elastase perfusion. A, Intact elastic fibers, as detected by Movat pentachrome stain (black), and SMαA-expressing cells (red) are increased in MCP1KO mice compared with WT mice. B, In contrast, medial cells of MCP1KO mice produce significantly less MMP2 (brown) as measured by immunostaining.

Because bone marrow–derived cells have been shown to be the key source of MMP9 within experimental AAAs,24 we further hypothesized that the inhibition of macrophage infiltration seen in the MCP1KO mice would be associated with a reduction of MMP9. Indeed, MMP9-producing cells were almost absent in the aortas of the MCP1KO mice (Figure 2, A). This indicates that MMP9 production in experimental AAAs occurs downstream of MCP1 signaling. However, results do not distinguish whether MCP1-mediated MMP9 production occurs by direct action on target cells and/or secondary to MCP1-dependent leukocyte recruitment and chemokine production.

Elastic Fibers and Differentiated SMCs Abundant in Aortic Wall of MCP1KOs

Increased inflammatory characterization and MMP production are thought to play major causative roles in the elastic fiber degradation that is a major hallmark of AAA.1 We next examined the extent to which MCP1KO affects elastic fiber content. The aortas of the MCP1KO treated with elastase had multiple intact layers of elastic fibers at day 14, with little to no degradation observed according to Movat pentachrome staining (Figure 2, B). Similarly, SMαA staining was far more evident in the aortic wall of the elastase-perfused MCP1KO than in the WT mice (Figure 2, B), consistent with increased fully differentiated SMCs in these vessels.

Because the SMC, or another nonbone marrow–derived cell type,2 is the essential source of MMP2 within AAAs, we further assayed MMP2 production in our tissues. Interestingly, the cells in the media of MCP1KO mice were almost universally negative for MMP2. This is a noticeable contrast to the media of the WT mice (Figure 2, B). Although the preceding data have established a role for MCP1-dependent pathways in regulating SMC phenotype and MMP2 production within AAAs, the data could not distinguish whether MCP1 plays a direct or indirect role in mediating these changes.

Knockout of MCP1 in Bone Marrow–Derived Cells Prevented AAA Formation, Medial Degradation, and Histologic Signs of Inflammation

Many AAA resident cell types have been shown to be capable of producing MCP1, including endothelial cells, SMCs, fibroblasts, natural killer cells, natural killer T cells, and macrophages. It is therefore uncertain whether MCP1 is predominantly produced by bone marrow–derived cells or vessel wall resident cells. To address this, we lethally irradiated WT and MCP1KO mice and rescued them with bone marrow from WT and MCP1KO donors. In all cases, successful and complete reconstitution of the host bone marrow and the identity of the host mice were validated using qPCR genotyping on peripheral blood cells and host tissues isolated at harvest. The control experiments performed with WT bone marrow transplanted into WT recipients (WT→WT) and with MCP1KO bone marrow transplanted into MCP1KO recipients (MCP1KO→MCP1KO) produced comparable results to those seen in nonirradiated mice. Interestingly, the WT mice that received bone marrow cells (BMCs) from MCP1KO mice (MCP1KO→WT) did not develop AAAs after elastase perfusion. In contrast, the MCP1KO mice that received BMCs from WT mice (WT→MCP1KO) showed the development of AAAs similar to the WT→WT mice (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Mice lacking monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1) in bone marrow do not form aneurysms after elastase perfusion. Wild type (WT) mice with bone marrow cells (BMCs) donated from MCP1KO mice (MCP1KO→WT) showed significant reduction in aortic dilation 14 days after elastase perfusion compared with WT mice with BMCs donated from WT mice (WT→WT) or MCP1KO mice with BMCs donated from WT mice (WT→MCP1; P < .0001). MCP1KO→WT mice also showed significantly increased protection compared with mice with MCP1KO BMCs transplanted into MCP1KO recipients (P = .0088).

To compliment these findings, the loss of MCP1 production in the bone marrow–derived cells appears sufficient to create a similar pattern of compositional changes in the vessel wall to those seen in the conventional, nonirradiated MCP1KO mice (Figure 2). Specifically, the MCP1KO to WT mice had an intact SMαA-rich media with multiple intact elastic fibers by Movat pentachrome staining and little to no MMP2. This result is contrasted by the WT→WT and WT→MCP1KO groups, which exhibit loss of elastic fibers and SMαA expression. Similarly, the infiltration of macrophages and upregulation of MMP9 and IL-1β seen in both the WT→WT and WT→MCP1KO groups are dramatically reduced in the MCP1KO→WT mice (Figure 4). Taken together, bone marrow–derived MCP1 appears crucial for both AAA progression and a number of major underlying compositional changes. These results indicate that development of experimental AAAs is dependent on MCP1 derived from BMCs and implies that the initial step in recruitment of bone marrow–derived cells to AAAs does not require MCP1, although MCP1 might play a redundant role in this process.

FIGURE 4.

Knockout of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1) in bone marrow cells (BMCs) decreases inflammatory markers and increases intact elastic fibers and SMαA expression. A, Immunohistochemistry performed 14 days after elastase perfusion indicates that expression of Mac2, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)2, MMP9, and interleukin 1β (IL-1β) is markedly diminished in MCP1KO→WT mice. B, This correlates with a significant increase in elastic fibers (black) and SMαA-expressing cells.

There is evidence from these studies, however, that MCP1 signaling plays a more complex role in AAA progression than being purely detrimental. The mean aortic dilation seen in the MCP1KO→WT group (15.9% ± 6.2%) was significantly lower than that seen in the MCP1KO→MCP1KO bone marrow transplantation group (57. 8% ± 11.0%, P = .009; Figure 3). This suggests that production of MCP1 by nonbone marrow–derived cells confers an unexpected advantage in attenuating the development of AAA. However, whether this relates to the cell type producing MCP1, the cell type responding to MCP1, the time at which MCP1 is produced by non-BMCs, or the amount of MCP1 produced cannot be definitively concluded from the existing data. Nevertheless, this “positive contribution” of nonbone marrow–derivedMCP1 is a novel and surprising observation and suggests that limited or selective abrogation of MCP1 might be more therapeutically beneficial than complete ablation.

MCP1 Represses Smooth Muscle Markers and Activates MMP Production in Cultured SMCs

The results described thus far have demonstrated a role for MCP1 in promoting macrophage infiltration and SMC phenotypic modulation in elastase-induced aneurysms. Although it possible that the effects on SMCs in vivo are indirect consequences of MCP1’s effects on the macrophage, an unexplored possibility exists that MCP1 can directly regulate SMC differentiation and MMP production. Because tested mouse SMC cultures exhibit variable expression of SMC differentiation marker genes, we treated an established rat SMC culture,21 previously published in mouse vascular biology studies10 and consistently exhibiting SMC marker expression with 0-, 0.5-, 5-, and 50-ng/mL recombinant MCP1. MCP1 repressed SMC differentiation marker gene expression (SMαA, SM22, and SM-MHC) in an apparently dose-dependent manner (Figure 5). In contrast, MCP1 induced both MMP2 and MMP9 expression in these experiments, consistent with the possibility that MCP1-mediated SMC phenotypic modulation might contribute to matrix degradation within AAAs (Figure 5). However, it is also possible that this induction of MMPs within SMCs might initiate a beneficial remodeling process by enhancing SMC migration, proliferation, and extracellular matrix deposition to stabilize the vessel wall.

FIGURE 5.

Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1) acts on cultured aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs) to repress SMC marker genes and induce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Cells treated with 0 to 50 ng/mL MCP1 showed a dose-dependent increase in (A) MMP2 and (B) MMP9 and coordinate with a decrease in (C) smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC), (D) SM22α, and (E) SMαA. *P < .05.

DISCUSSION

The data presented in the present study have demonstrated that MCP1KO mice are resistant to experimental aneurysm formation. This protective effect is preserved after transplantation of BMCs from MCP1KO mice into irradiated WT hosts. Taken together, these results indicate that bone marrow–derived MCP1 is required for experimental AAA formation. Mac2, MMP2, MMP9, and IL-1β expression are markedly decreased and SMαA expression is markedly increased in the aortas from both global MCP1KO mice and mice with MCP1KO bone marrow transplanted into WT hosts. Furthermore, MCP1 is capable of promoting MMP expression and repressing SMC markers directly on cultured aortic SMCs in vitro, indicating MCP1 might play important roles by way of both cytokine and chemotactic functions. Although our laboratory has only recently been the first to report that SMC phenotypic modulation occurs within AAA,5 previous studies reporting the importance of normal SMC contractile protein expression,6 and nonbone marrow–derived MMP22 indicate MCP1’s actions on SMCs might be important to disease progression.

It is clear from these results that MCP1 is essential for both aneurysm formation and the corresponding changes in SMC phenotype. However, the determination of the relevance of the direct action of MCP1 on SMCs in vivo is complicated by conflicting reports regarding whether CCR2 is expressed on SMCs.15,16 Furthermore, MCP1 has been shown to induce tissue factor in SMCs derived from CCR2 KO mice, indicating that CCR2 is not required for all MCP1-dependent effects.16 CCR2 could not be detected by Western blotting or qPCR on our cultured SMCs, despite a robust signal from rat spleen and monocyte lysates, corroborating a possible CCR2-independent signaling pathway in SMCs (data not shown). However, efforts to identify a second receptor for MCP1 under physiologic conditions have not produced a viable result.16 Additional study into this area is therefore required to decipher the full in vivo relevance of MCP1’s cytokine-like actions on SMCs, despite the importance inferred by MMP2 knockout studies.2 More importantly, because the current preclinical strategies for AAA have focused heavily on targeting innate or adaptive immune cells, identifying how MCP1 acts on SMCs might identify a novel drug target for AAA.

Despite this controversy, our results have clearly demonstrated that MCP1 produced by bone marrow–derived cell types is required for AAA formation, SMC phenotype, and macrophage influx in the elastase perfusion model. Furthermore, a major novel and unexpected finding was that MCP1 from non-BMC sources appears to have beneficial effects in reducing AAA formation in that loss of MCP1 exclusively in bone marrow–derived cell types (Figure 3) was of added benefit compared with the loss of MCP1 globally. This observation is potentially more interesting given the resistance of tissue-resident macrophages to radiation. Although it is not possible to rule out the partial loss of tissue-resident macrophages after irradiation as a contributor to the observed phenotype, the results clearly imply that the required cellular source of MCP1 is radiosensitive.

Although determining the precise mechanism of this observation will require extensive additional studies, there are a few possible explanations, each of which might not be mutually exclusive. First, there might be spatial-temporal differences in MCP1 production in BMCs versus non-BMCs that play a key role in AAA development and/or progression. However, the existence of a spatially or temporally “opposite” role for MCP1 produced by BMCs versus non-BMCs is contraindicated by the fact that MCP1KO in non-BMCs (WT→MCP1KO, Figure 3) did not exacerbate AAA formation compared with WT→WT (Figure 3) or conventional MCP1KO (Figure 1). Alternatively, it might be the total amount of MCP1 that is critical. For example, the production of low concentrations of MCP1 might provoke a sufficient “destructive” response to allow remodeling and/or repair of the vessel wall. In contrast, the production of high levels of MCP1 by BMCs within the vessel wall might be detrimental and lead to progressive inflammation and exacerbation of AAA formation, delaying or preventing a “reparative” response. Given this scenario, the data suggest bone marrow–derived cells are required for MCP1 levels to reach a destructive threshold. In such a scenario, one would expect forcing elevated production of MCP1 in the vessel wall using an inducible, cell type-specific promoter, to be capable of driving AAA progression in the absence of MCP1 in bone marrow–derived cells.

The role of immune cells, inflammation, and MMPs in promoting AAA has been well documented.1 However, a reparative role for the monocyte/macrophage in AAA has not been explored. Notably, the monocyte/macrophage has been identified as a key contributor of pro-healing factors in other diseases, including myocardial ischemia.25 Furthermore, there is evidence that these “reparative” macrophage actions do not take place if “destructive” macrophages are prevented from first entering.25 Although the existence of a “reparative” macrophage has not been identified within AAA, the results presented similarly suggest that an ideal anti-inflammatory therapy for AAA would not globally ablate all aspects of the immune response but only those most essential for the destructive aspects of inflammation.

This study had several limitations. Although the elastase perfusion model is acute, with AA formation within a 2-week period, this model does mimic aspects of human disease with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate. Moreover, this model has led to important insights regarding the mechanisms of aneurysms formation.1,3,4 Nevertheless, it is important to note this model is an artificial method of creating an aneurysm. In addition, the use of “normal” aorta from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting can be questioned. There might be some regional differences in the aorta between the thoracic and abdominal aorta. Ideally, normal abdominal aorta from healthy age-matched patients would be a more appropriate control; however, such tissue is difficult to obtain, and coronary artery bypass grafting tissue has the advantage of being readily available.

CONCLUSIONS

The data presented in this study indicate MCP1 is essential to the progression of AAA. Importantly, MCP1 signaling plays an essential role in both macrophage influx and smooth muscle phenotypic modulation within AAAs. Interestingly, however, our data indicate that complete inhibition of MCP1 might not be as beneficial to inhibiting aortic dilation as inhibition of MCP1 only in bone marrow–derived cells. Additional study of this phenomenon and the identification of factors or small molecules capable of interfering with MCP1 production selectively in bone marrow–derived cells, might yield important insights into the design of maximally beneficial AAA therapies.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank John Sanders and Melissa Brevard of the University of Virginia Cardiovascular Research Center Histology Core for their assistance and expertise with the histologic examinations in this study. We would also like to thank Rupa Tripathi and Sandra Walton for their expertise with SMC cultures.

Funding for this project and the investigators was provided by the National Institutes of Health Cardiovascular Surgery Research Training grant T32/HL007849 (to C.M.B.), the National Institutes of Health Basic Cardiovascular Research Training grant T32/HL007284 (to C.W.M.), the Thoracic Surgery Foundation for Research and Education Research grant (to G.A.), and National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant K08 HL098560 (to G.A.).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AAs

aortic aneurysms

- AAA

abdominal aortic aneurysm

- BMC

bone marrow cell

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- MCP1

monocyte chemotactic protein 1

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SmαA

smooth muscle α-actin

- SMCs

smooth muscle cells

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

References

- 1.Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Upchurch GR., Jr Current concepts in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:584–588. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longo GM, Xiong W, Greiner TC, Zhao Y, Fiotti N, Baxter BT. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 work in concert to produce aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:625–632. doi: 10.1172/JCI15334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson RW, Curci JA, Ennis TL, Mao D, Pagano MB, Pham CT. Pathophysiology of abdominal aortic aneurysms: insights from the elastase-induced model in mice with different genetic backgrounds. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1085:59–73. doi: 10.1196/annals.1383.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson RW, Holmes DR, Mertens RA, et al. Production and localization of 92-kilodalton gelatinase in abdominal aortic aneurysms: an elastolytic metalloproteinase expressed by aneurysm-infiltrating macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:318–326. doi: 10.1172/JCI118037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ailawadi G, Moehle CW, Pei H, Walton SP, Yang Z, Kron IL, et al. Smooth muscle phenotypic modulation is an early event in aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:1392–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.07.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milewicz DM, Guo DC, Tran-Fadulu V, Lafont AL, Papke CL, Inamoto S, et al. Genetic basis of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections: focus on smooth muscle cell contractile dysfunction. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:283–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozaki K, Kaminski WE, Tang J, Hollenbach S, Lindahl P, Sullivan C, Yu JC, et al. Blockade of platelet-derived growth factor or its receptors transiently delays but does not prevent fibrous cap formation in ApoE null mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1395–1407. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64415-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raines EW. PDGF and cardiovascular disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holycross BJ, Blank RS, Thompson MM, Peach MJ, Owens GK. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB-induced suppression of smooth muscle cell differentiation. Circ Res. 1992;71:1525–1532. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.6.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas JA, Deaton RA, Hastings NE, Shang Y, Moehle CW, Eriksson U, et al. PDGF-DD, a novel mediator of smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation, is upregulated in endothelial cells exposed to atherosclerosis-prone flow patterns. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H442–H452. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00165.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement N, Gueguen M, Glorian M, Blaise R, Andreani M, Brou C, et al. Notch3 and IL-1beta exert opposing effects on a vascular smooth muscle cell inflammatory pathway in which NF-kappaB drives crosstalk. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 19):3352–3361. doi: 10.1242/jcs.007872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loppnow H, Werdan K, Buerke M. Vascular cells contribute to atherosclerosis by cytokine- and innate-immunity-related inflammatory mechanisms. Innate Immunity. 2008;14:63–87. doi: 10.1177/1753425908091246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu B, Rutledge BJ, Gu L, Fiorillo J, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, et al. Abnormalities in monocyte recruitment and cytokine expression in monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:601–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurihara T, Warr G, Loy J, Bravo R. Defects in macrophage recruitment and host defense in mice lacking the CCR2 chemokine receptor. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1757–1762. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spinetti G, Wang M, Monticone R, Zhang J, Zhao D, Lakatta EG. Rat aortic MCP-1 and its receptor CCR2 increase with age and alter vascular smooth muscle cell function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1397–1402. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134529.65173.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schecter AD, Berman AB, Yi L, Ma H, Daly CM, Soejima K, et al. MCP-1-dependent signaling in CCR2−/− aortic smooth muscle cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:1079–1085. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0903421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacTaggart JN, Xiong W, Knispel R, Baxter BT. Deletion of CCR2 but not CCR5 or CXCR3 inhibits aortic aneurysm formation. Surgery. 2007;142:284–288. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishibashi M, Egashira K, Zhao Q, Hiasa K, Ohtani K, Ihara Y, et al. Bone marrow-derived monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 is critical in angiotensin II-induced acceleration of atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:e174–e178. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143384.69170.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.deWaard V, Bot I, de Jager SC, Talib S, Egashira K, de Vries MR, et al. Systemic MCP1/CCR2 blockade and leukocyte specific MCP1/CCR2 inhibition affect aortic aneurysm formation differently. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Roelofs KJ, Sinha I, Hannawa KK, Kaldjian EP, et al. Gender differences in experimental aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2116–2122. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143386.26399.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu RT, Blank RS, Jervis R, Lawrenz-Smith SC, Owens GK. The smooth muscle alpha-actin gene promoter is differentially regulated in smooth muscle versus non-smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7631–7643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch AE, Kunkel SL, Pearce WH, Shah MR, Parikh D, Evanoff HL, et al. Enhanced production of the chemotactic cytokines interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1423–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colonnello JS, Hance KA, Shames ML, Wyble CW, Ziporin SJ, Leidenfrost JE, et al. Transient exposure to elastase induces mouse aortic wall smooth muscle cell production of MCP-1 and RANTES during development of experimental aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:138–146. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pyo R, Lee JK, Shipley JM, Curci JA, Mao D, Ziporin SJ, et al. Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1641–1649. doi: 10.1172/JCI8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce GF, Mustoe TA, Lingelbach J, Masakowski VR, Griffin GL, Senior RM, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta enhance tissue repair activities by unique mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:429–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]