Milestone: 1. A stone marker set up on a roadside to indicate the distance in miles from a given point. 2. An important event, as in a person's career, the history of a nation, or the advancement of knowledge in a field; a turning point.1

Background

The United States health care system and graduate medical education are undergoing intense and inter-dependent transformation. The Institute of Medicine's (IOM) 2001 Crossing the Quality Chasm report2 argued that the U.S. health care delivery system failed to provide consistent, high quality medical care and was poorly organized to meet the changing public health landscape. In response, health care systems, providers, and payers have embarked on a journey to reach the “Triple Aims” of better care for individuals, better health for populations, and reducing per capita health care costs. Reforms underway in health care payment structures will likely have major, not yet fully understood effects on U.S. health care and graduate medical education (GME).3

In 1997 the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medicine Education (ACGME) initiated the Outcome Project. Paralleling the IOM focus on quality and safety, the Outcome Project shifted GME's focus from processes towards trainee and program performance. During this period numerous other forces, including duty hour limits and new technologies, shaped GME.

As a result, GME training has become increasingly complex in content, program requirements, and assessment modalities. These developments have forced programs to greatly expand administration supports. The administrative burden on designated institutional officials, program directors, and faculty may threaten teaching efforts and resident learning. The administrative load has been compounded by increased financial burdens on institutions during this era of health care reform; these are likely to worsen if funding for GME declines.

In response to this “perfect storm,” GME educators and researchers created new paradigms to frame training with the goal of graduating physicians able to provide high quality, safe, and cost-effective care. The Outcome Project introduced specialty-defined physician competencies aggregated into 6 general areas, which recognized that physician competence entails multiple domains.4 Identification of specialty-specific competencies spurred development of tools to measure them, which has met with mixed success.5 As the number of subcompetencies expanded, each requiring assessment, efforts to describe the typical progression of physician competence led to the concepts of educational milestones and entrustable professional activities (EPAs). ten Cate and Scheele advanced EPAs as a way to describe the essential characteristics of independent practitioners, which could guide decisions regarding resident independence.6,7

A key tenet of competency-based education is that proficiency progresses on a continuum within each specialty-specific domain.4 As a result several specialties have developed educational milestones to create a blueprint for trainee progress during residency.8 In the most basic explanation, the milestones add a timeline and benchmarks to resident progression towards independent practice. In assigning a timeline to the milestones, some specialties have employed a framework for acquisition of expertise, such as the 5-level Dreyfus and Dreyfus model (novice, beginner, competent, proficient, expert).9,10 Others have determined the point during residency at which an individual milestone should usually be achieved.9,10

Milestones Development

In July 2013, the next phase of the ACGME Outcome Project begins for 7 specialties through the Next Accreditation System (NAS).11 These NAS Phase I specialties have modified existing milestones or created new milestones to fit the NAS reporting requirements, which include reporting of performance every 6 months. Reporting requirements will be implemented for Phase II specialties in July 2014.11

As originally conceived, milestones were intended to describe the progression of resident competence during training and to culminate in achievement of independent practice. One of the first specialties to create milestones, Internal Medicine, created behavioral milestones matched to the time period during residency when most residents would be expected to reach a particular level; these developmental milestones have been in use for 3 years. In response to the NAS reporting requirements, the original milestones were reconfigured into 142 reporting milestones. Preliminary data regarding feasibility and accurateness for resident assessment are available from pilot testing.12 Results from 37 residency programs demonstrated that these milestones were logical; represented a realistic progression of resident knowledge, attitudes, and skills; could be evaluated with current assessment tools; and represented the Internal Medicine Residency Review Committee requirements. Educators also reported that using the composite reporting milestones took considerable time and assigning a resident to a single level was difficult, as each level contained multiple different sublevels formed from the original developmental milestones.12

Overview of the First Specialties' Milestones

In the March 2013 issue of JGME, Swing and colleagues describe the various processes used by the first 7 specialties to create milestones for reporting, as well as initial steps towards establishing their content validity.13 This supplement contains the milestones developed by Emergency Medicine, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Orthopedic Surgery, Pediatrics, Diagnostic Radiology, and Urology. Working separately, each specialty derived unique ways to conceptualize new or reformat existing milestones, beyond the expected differences in content. We believe that these different interpretations will stimulate important studies of milestones by GME educators.

The milestones developed by the first 7 specialties vary in number, specificity of content, and time assignment during residency. The surgical milestones—Neurological Surgery, Orthopedic Surgery, and Urology—provide detailed content for each milestone and delineate separate procedural milestones. The Pediatrics and Internal Medicine milestones are described in more general terms, in narrative format. While both approaches have merit, evaluation strategies will likely be different. The detailed surgical milestones will result in less ambiguity in terms of achievement: residents, faculty, and program directors will understand successful performance at each level. However, the level of detail that may include 10 sublevels below a level, under a single competency, may place a substantial burden upon programs.

In comparison the Pediatrics milestones are general statements of performance that relate to descriptions of entrustable professional activities required for graduation. Each statement will need to be interpreted consistently by individual residents, faculty, and others involved in the teaching program. Successful interpretation of narratives at each level will require ongoing faculty training and consensus development. Interpreting each narrative and aligning it to assessments with validity evidence will be necessary. Novel methods will need to be developed in order to train faculty and assess residents using these narratives.

With elements of both competence specificity and descriptive narratives, the milestones for Urology and Emergency Medicine strike a balance between narrative and behavioral approaches. The Urology milestones also include concrete examples of resident behaviors for each level or achievement within the milestone; these examples should prove helpful to programs as they integrate the milestones within existing residency activities.

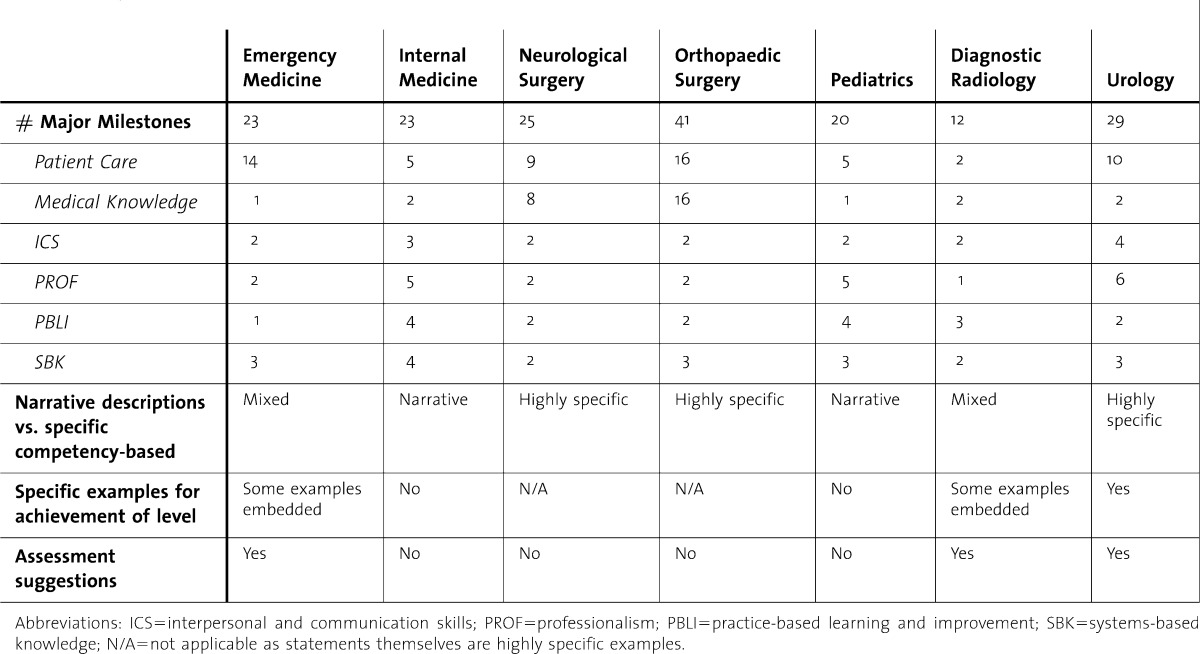

For the most part the milestones for interpersonal skills and communication, professionalism, practice-based learning and improvement, and systems-based knowledge remain generic, not specific to each specialty. There are exceptions: inclusion of communication with the operating room team for Urology; practice consistent with American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery professionalism standards for the Orthopedic Surgery milestones; and specific patient communication challenges for Emergency Medicine. It is likely that programs will find implementation as well as assessment of these milestones more feasible with either milestone language specific to the practice scope of the specialty or examples of resident achievement that relate directly to specialty practice. The Table compares the milestones from the 7 specialties to illuminate potential areas for further study.

Table.

Specialty Milestones Snapshot

To date, the initial review of the milestones for Phase I specialties has raised these questions:

Should all specialties have the same proficiency expectations for similar core competencies (eg, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, systems-based practice, practice-based learning and improvement)?

Are the milestones aligned with the physician roles and needs of our future health care system, such as team-based care, prevention, care of populations, cost and efficiency, and safety?

How will specialties and programs accurately assess trainees at each milestone level and who will perform these assessments (physicians, other health care team members, patients, health care system quality/safety officers)?

Are the milestones stated in terms that support consistent assessments between raters?

How will programs approach faculty development?

Challenges Ahead

Although the establishment and assessment of milestones represent an exciting and important theoretical advance for GME, numerous challenges, which we view as opportunities for innovation, lie ahead. The establishment of uniform milestones and assessments will require additional validity evidence and substantial faculty development. Currently programs have little discretionary time for expanded educational tasks. In response, some institutions are building new information technology, such as bedside portable systems, to facilitate data recording in real time, interaction between programs, and simplified data transfer to ACGME. Specialty communities, programs and sponsors will need to build assessment measures that are efficient and cost effective, as well as accurate.

NAS-required reporting of performance outcomes at 6 month intervals seeks to ease ACGME oversight of programs and public reporting of educational outcomes.11 ACGME also encourages real time assessment of residents' knowledge, skills and attitudes as they are performing assigned duties.11 This approach is intended to reduce the separation of assessment from daily practice and provide a more accurate measure of performance. However this aspiration will require study in order to determine whether the NAS reporting intervals will facilitate assessment or enhance the validity of measurements.

An area of concern for many GME educators is not the actual development of the milestones—as educators understand the need for consensus regarding levels of achievement during residency training—but whether the milestones will lead to more efficient, less burdensome, and more accurate assessment of resident performance. The need to assure the public and medical profession that graduates are capable of safe, independent practice must be balanced with anticipated declines in GME funding and the overall lack of validity evidence for existing competencies, milestones, and assessment tools.14 Competencies and milestones that have been developed by stakeholder consensus will require evaluation to determine whether they produce teaching programs and assessment strategies that yield the desired high quality medical practitioner. The urgency to implement and report milestones must occur in parallel with robust research, both quantitative and qualitative, to examine the effects of these initiatives on residency programs and their graduates.

Few educators today would support the use of a single test (eg, board examination) or any other single assessment to certify residents as safe to practice independently. Research to demonstrate which assessments predict high quality physician practice will require longitudinal databases that may be possible only with funded studies. In the absence of data from longitudinal research on the effectiveness of the milestones, the political agenda of the day may direct rather than inform medical training and consensus may replace evidence.

Summary

The definition of the current competencies as well as their optimal assessment has remained controversial.14,15 The purpose of competency assessment will need to be clarified, beyond formative vs. summative. Multiple agendas derived from different stakeholders may need to give way to the few that directly impact the goal of producing high caliber, independent practitioners.16 Streamlining the various purposes for assessment will be an important issue for the embryonic milestones as well.

The reality for most training programs is that the supply of time and money is decreasing. No matter how laudable the goals of valid, reliable, and national educational outcomes, their implementation must be feasible within this reality. Therefore cost-effectiveness will need to be considered in future assessment studies. We must ensure the competent performance of graduate physicians, in the right balance of specialties, at a reduced cost to the nation; the milestones project may well be measured by how well it contributes to these aims. Will milestones advance the field of assessment and mark a turning point in GME? We urge readers to continue to the national conversation that seeks answers to these questions.

Footnotes

JGME invites you to join the conversation on the educational milestones:

References

- 1. The Free Dictionary. http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Milestones. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- 2.Richardson WC, Berwick DM, Bisgard JC, Bristow LR and the Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy of Sciences. 2000. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-A-New-Health-System-for-the-21st-Century.aspx. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- 3.Song Z., Lee TH. The era of delivery system reform begins. JAMA. 2013;309(1):35–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.96870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank JR, Snell LS, Ten Cate O, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32:628–645. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lurie SJ, Mooney CJ, Lyness JM. Measurement of the General Competencies of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Acad Med. 2009;84:301–309. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181971f08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 2007;82(6):542–547. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31805559c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ten Cate O. Nuts & Bolts of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):157. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green ML, Aagaard EM, Caverzagie KJ, Chick DA, Holmboe E, Kane G, et al. Charting the Road to Competence: Developmental Milestones for Internal Medicine Residency Training. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1:5–20. doi: 10.4300/01.01.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreyfus HL, Dreyfus SE. Mind over machine: the power of human intuitive expertise in the era of the computer. New York: Free Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pena A. The Dreyfus model of clinical problem-solving skills acquisition: a critical perspective. Med Educ Online. http://med-ed-online.net/index.php/meo/article/view/4846/pdf_3. Accessed January 15, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next accreditation system rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iobst W, APDIM presentation, http://www.im.org/Meetings/Past/2012/AIMW12/Presentations/Pages/2012APDIMFallMeeting.aspx. Accessed January 20, 2013.

- 13.Swing S, Beeson MS, Carraccio C, Coburn M, Iobst W, Selden NR, et al. Educational Milestone Development in the First 7 Specialties to Enter the Next Accreditation System. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):98–106. doi: 10.4300/JGME-05-01-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lurie SJ. History and practice of competency-based assessment. Med Educ. 2012;46:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albanese MA, Mejicano G, Mullan P, Kokotailo P, Gruppen L. Defining characteristics of educational competencies. Med Educ. 2008;42:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amin Z. Purposeful assessment. Med Educ. 2012;46:4–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]