Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) is a rare condition occurring in 1/600 to 1/2000 pregnancies [Dunnihoo et al. 1991; Ortin et al. 2005] mainly in the postpartum setting. It is also known to be associated with other conditions such as malignancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammatory bowel disease, sepsis and recent pelvic or abdominal surgery [Andre et al. 2004; Heavrin and Wrenn, 2008; Jacoby et al. 1990; Klima and Snyder, 2008; Marcovici and Goldberg, 2000; Salomon et al. 1999; Simons et al. 1993]. It is extremely rare to find OVT without identified etiology and, hence, idiopathic OVT is only described as case reports throughout the literature. Here, we report a unique case of idiopathic isolated OVT that presented with right flank pain and an abdominal mass. Although four similar cases of idiopathic isolated OVT have been reported in the literature [Heavrin and Wrenn, 2008; Murphy and Parsa, 2006; Stafford et al. 2010; Yildirim et al. 2005], none of these patients presented with an abdominal mass. The diagnosis of isolated OVT requires a high index of suspicion. If misdiagnosed, OVT can lead to potentially fatal complications such as sepsis and pulmonary embolism. [Benfayed et al. 2003; Kominiarek and Hibbard, 2006; Maldjian and Zurlow, 1997; Wysokinska et al. 2006].

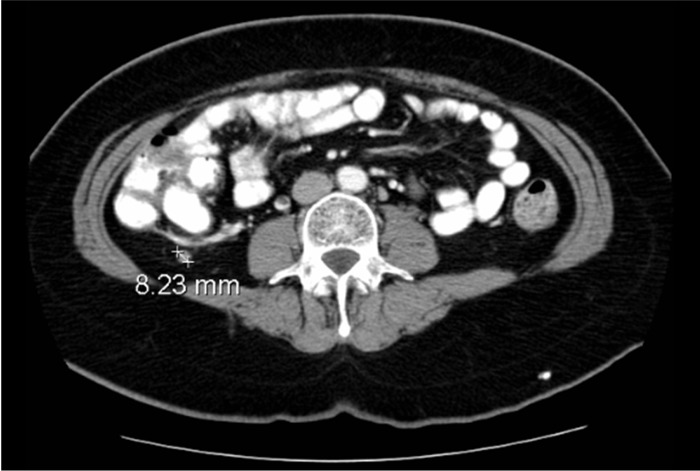

A 53-year-old postmenopausal woman with a past medical history of hypertension presented to the medical clinic complaining of 1-week history of aching right flank pain that was not associated with fever, dysuria, hematuria, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or vaginal discharge. The patient denied any other constitutional symptoms. She is a nonsmoker with no family history of hematologic disorders. On physical examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, without tachycardia. Pelvic exam revealed a nontender, normal size uterus and adnexa. However, a 3 cm tender mass was palpated in the right lower quadrant. Laboratory data revealed a white blood cell count of 4400-cells/mm3 and hemoglobin level 11.9 g/dl. Renal function and electrolytes were within normal limits. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast showed right ovarian vein thrombus without extension to the inferior vena cava (IVC) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CT scan at presentation.

Further work up for hypercoagulability was negative. Age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings were all negative. Moreover, screening for ovarian pathology, with pelvic ultrasound and CA-125, was also normal. Shortly after the diagnosis of isolated OVT, the patient was placed on oral anticoagulation. It was elected not to administer antibiotics. Warfarin was continued for 5 months with the International Normalized Ratio (INR) maintained between 2 and 3. A follow-up CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed 5 months later showed persistence of the thrombus with no further extension beyond the ovarian vein (see Figure 2). Anticoagulation was discontinued at this point with close clinical follow up.

Figure 2.

CT scan after 5 months of anticoagulation therapy.

Ovarian vein thrombosis was first described by Austin in 1956 [Austin, 1956]. It occurs in the right side in 70–90% of cases, and bilaterally in 11–14% [Baran and Frisch, 1987; Prieto-Nieto et al. 2004]. The most widely accepted hypothesis for the higher incidence on the right is that the right ovarian vein is longer than the left, and lacks competent valves. The typical presentation is the triad of pelvic pain, fever, and a right-sided abdominal mass [Dessole et al. 2003; Dunnihoo et al. 1991; Klima and Snyder, 2008; Prieto-Nieto et al. 2004]. Fever is present in 80% and right iliac fossa pain in 55% of the patients [Prieto-Nieto et al. 2004]. Given the nonspecific presenting symptoms, prompt diagnosis of OVT requires a high index of suspicion. The differential diagnosis includes most conditions that affect the abdominal lower quadrant such as acute appendicitis and inflammatory bowel diseases. Therefore, imaging studies are essential to establish the diagnosis of OVT. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) has the highest sensitivity and specificity that approaches 100%. CT scan with intravenous contrast enhancement has a sensitivity of 77.8% and specificity of 62.5%. Color Doppler ultrasound has the lowest sensitivity of 55.6% and a specificity of 41.5% among other imaging modalities [Kubik-Huch et al. 1999].

A delay in the diagnosis and treatment of OVT can lead to potentially life-threatening complications, such as thrombus extension into the IVC or ileofemoral vessels and eventually the evolution of pulmonary arterial embolization. The incidence of pulmonary embolism is approximately 25% in patients with untreated OVT and the mortality in these patients can reach about 4% [Benfayed et al. 2003; Dunnihoo et al. 1991; Kominiarek and Hibbard, 2006]. Other serious complications include septic thrombophlebitis and, rarely, infectious emboli [Dessole et al. 2003; Heavrin and Wrenn, 2008]. Ovarian vein thrombosis can resolve spontaneously but considering the potential catastrophic consequences, anticoagulation is usually recommended [Wysokinska et al. 2006]. There is no definite guideline regarding the duration of anticoagulation therapy. Wysokinska and colleagues studied the incidence and the recurrence of OVT compared with lower extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT) [Wysokinska et al. 2006]. None of the 35 patients in the OVT group was idiopathic and the recurrence rate was comparable to patients diagnosed with lower extremity DVT (3 per 100 patient years of follow up). The average treatment with warfarin was 5.3 and 6.9 months for OVT and lower extremity DVT, respectively. Based on these findings, the authors suggested the application of lower extremity guidelines for the treatment of OVT.

Antibiotics can also be administered for approximately 7 days especially in cases of postpartum OVT [Brown and Munsick, 1971; Dessole et al. 2003; Maldjian and Zurlow, 1997; Wysokinska et al. 2006]. In patients with hypercoagulable disorders, anticoagulation may need to be lifelong therapy [Wysokinska et al. 2006]. In rare cases of persistent OVTs, an IVC filter or surgical intervention to ligate the ovarian vein can be considered [Carr and Tefera, 2006; Clarke and Harlin, 1999].

Our patient was diagnosed with an idiopathic OVT since none of the above predisposing factors for OVT were found. The patient’s abdominal pain subsided few days after starting anticoagulation and she did not develop any worrisome signs such as fever, dyspnea, or chest pain. Five years later, the patient remains asymptomatic while off anticoagulation, without any further thrombotic conditions.

To date, four cases of idiopathic OVT were described [Heavrin and Wrenn, 2008; Murphy and Parsa, 2006; Stafford et al. 2010; Yildirim et al. 2005]. None of these cases had abdominal or pelvic palpable masses at presentation. Therefore, our report describes a unique case of idiopathic OVT presenting with one symptom and one sign of the typical triad. The palpable mass in the right iliac fossa was only described in cases of OVT that occur in the postpartum period as well as in other inflammatory and hypercoagulable conditions.

OVT is a rare condition with potential life-threatening complications. In female patients presenting with lower quadrant pain, with or without fever or palpable abdominal or pelvic mass, OVT should be considered in the differential diagnosis after ruling out other common conditions. MRA and CT scan with intravenous contrast are the most useful imaging modalities to diagnose this condition. Overlooking this diagnosis can lead to life-threatening conditions, such as pulmonary embolism, sepsis, and even death. Hence, prompt diagnosis of OVT requires a high index of suspicion in order to prevent these outcomes.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Contributor Information

Kassem Harris, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Suchita Mehta, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Edward Iskhakov, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Michel Chalhoub, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Theodore Maniatis, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Frank Forte, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Homam Alkaied, Staten Island University Hospital, 475 Seaview Avenue, Staten Island, NY 10305, USA.

References

- Andre M., Delevaux I., Amoura Z., Corbi P., Courthaliac C., Aumaitre O., et al. (2004) Ovarian vein thrombosis in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 50: 183–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin O.G. (1956) Massive thrombophlebitis of the ovarian veins; a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 72: 428–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baran G.W., Frisch K.M. (1987) Duplex Doppler evaluation of puerperal ovarian vein thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 149: 321–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfayed W.H., Torreggiani W.C., Hamilton S. (2003) Detection of pulmonary emboli resulting from ovarian vein thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 181: 1430–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T.K., Munsick R.A. (1971) Puerperal ovarian vein thrombophlebitis: a syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 109: 263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr S., Tefera G. (2006) Surgical treatment of ovarian vein thrombosis. Vasc Endovascular Surg 40: 505–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C.S., Harlin S.A. (1999) Puerperal ovarian vein thrombosis with extension into the inferior vena cava. Am Surg 65: 147–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessole S., Capobianco G., Arru A., Demurtas P., Ambrosini G. (2003) Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis: an unpredictable event: two case reports and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 267: 242–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnihoo D.R., Gallaspy J.W., Wise R.B., Otterson W.N. (1991) Postpartum ovarian vein thrombophlebitis: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 46: 415–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heavrin B.S., Wrenn K. (2008) Ovarian vein thrombosis: a rare cause of abdominal pain outside the peripartum period. J Emerg Med 34: 67–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby W.T., Cohan R.H., Baker M.E., Leder R.A., Nadel S.N., Dunnick N.R. (1990) Ovarian vein thrombosis in oncology patients: CT detection and clinical significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 155: 291–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klima D.A., Snyder T.E. (2008) Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Obstet Gynecol 111: 431–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kominiarek M.A., Hibbard J.U. (2006) Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis: an update. Obstet Gynecol Surv 61: 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubik-Huch R.A., Hebisch G., Huch R., Hilfiker P., Debatin J.F., Krestin G.P. (1999) Role of duplex color Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography, and MR angiography in the diagnosis of septic puerperal ovarian vein thrombosis. Abdom Imaging 24: 85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian P.D., Zurlow J. (1997) Ovarian vein thrombosis associated with a tubo-ovarian abscess. Arch Gynecol Obstet 261: 55–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcovici I., Goldberg E. (2000) Ovarian vein thrombosis associated with Crohn’s disease: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 182: 743–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C.S., Parsa T. (2006) Idiopathic ovarian vein thrombosis: a rare cause of abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med 24: 636–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortin X., Ugarriza A., Espax R.M., Boixadera J., Llorente A., Escoda L., et al. (2005) Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 93: 1004–1005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Nieto M.I., Perez-Robledo J.P., Rodriguez-Montes J.A., Garci-Sancho-Martin L. (2004) Acute appendicitis-like symptoms as initial presentation of ovarian vein thrombosis. Ann Vasc Surg 18: 481–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon O., Apter S., Shaham D., Hiller N., Bar-Ziv J., Itzchak Y., et al. (1999) Risk factors associated with postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 82: 1015–1019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons G.R., Piwnica-Worms D.R., Goldhaber S.Z. (1993) Ovarian vein thrombosis. Am Heart J 126: 641–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford M., Fleming T., Khalil A. (2010) Idiopathic ovarian vein thrombosis: a rare cause of pelvic pain - case report and review of literature. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 50: 299–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysokinska E.M., Hodge D., McBane R.D., II (2006) Ovarian vein thrombosis: incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism and survival. Thromb Haemost 96: 126–131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim E., Kanbay M., Ozbek O., Coskun M., Boyacioglu S. (2005) Isolated idiopathic ovarian vein thrombosis: a rare case. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 16: 308–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]