Abstract

Introduction

The aim of the Rural Older Adult Memory pilot study (ROAM) was to evaluate the feasibility of screening and diagnosing dementia in patients aged 75 years or older in six rural primary care practices in a practice—based research network.

Methods

Clinicians and medical assistants were trained in dementia screening using the ROAM protocol, via distance learning methods. Medical assistants screened patients aged 75 and older. For patients who screened positive, the clinician was alerted to the need for a dementia work-up. Outcomes included change in the proportion of patients screened and diagnosed with dementia or mild cognitive impairment and clinician confidence in diagnosing and managing dementia. Patient, medical assistant, and clinician response to the intervention were also evaluated.

Results

Results included a substantial increase in screening for dementia, a modest increase in the proportion of cases diagnosed with dementia or mild cognitive impairment, and improved clinician confidence in diagnosing dementia. Although clinicians and medical assistants found the ROAM protocol easy to implement, there was substantial variability in adherence to the protocol in the six practices.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the complex issues that must be addressed in implementing a dementia screening process in rural primary care. Further study is needed to develop effective strategies for overcoming the factors that impeded the full uptake of the protocol, including the logistical challenges in implementing practice change and clinician attitudes towards dementia screening and diagnosis.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, dementia screening, primary care, clinical practice change, rural healthcare

Dementia is common in older adults, estimated at 11% - 16% of people older than 70 (1). Often, a primary care clinician (PCP) is the only clinician available to older patients with memory complaints, but numerous studies have found that as many as 50% of patients with dementia do not have a diagnosis of dementia documented in their medical chart (2-5). The subtlety of symptoms and time constraints in primary care practice make it challenging for PCPs to recognize and diagnose dementia (6,7).

Although the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has not recommended screening for dementia (8),. Alzheimer's disease experts identify a number of reasons why diagnosis is important, including ruling out treatable conditions that can cause cognitive impairment (e.g., medication effects, cardiovascular conditions, or depression)(9), offering treatments for cognitive and behavioral symptoms of dementia (10), maintaining the patients' safety (11), and support for the family (12). Given clinicians' reliance on patients' memory for symptom reporting and adherence to treatment recommendations, the identification of cognitive impairment in patients is essential (13-15).

Several studies to improve the diagnosis of dementia conducted in academic and/or urban settings have had varying degrees of success (3,16,17). This is the first known study to test a dementia screen and diagnosis intervention in rural primary care. Improving dementia care is particularly challenging in rural areas where access to community resources, including medical specialists, are limited and primary care workloads are greater than in urban areas (18,19).

Practice-based research networks (PBRN's) offer a promising approach to improving primary care as clinicians and their staff are directly engaged in testing practice changes (20,21). Among other resources, PBRNs can provide direct assistance to practices engaged in the quality improvement studies through a “change facilitator” (22).

The ROAM study was carried out in the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN) a statewide network of 46 primary care practices in 35 communities that serve approximately 223,000 patients. Our aim was to evaluate the feasibility of ROAM for dementia screening and diagnosis in six rural practices that were members of ORPRN. We adapted the materials and procedures for the dementia-specific component of the Assessing Care of the Vulnerable Elders model (ACOVE), developed by geriatric experts at UCLA and Rand (17). ACOVE uses five clinic-based methods to improve practice: efficient collection of condition-specific clinical data, medical record prompts to encourage performance of essential care processes, patient education materials and activation of the patient's role in follow-up, physician decision support, and physician education. Preliminary tests of this model found it to be feasible in urban and suburban practices but to our knowledge, it has not been tested in rural practices. Furthermore, the ACOVE model has had limited testing of its dementia component as a single-condition intervention.

Methods

Study Setting

The OHSU Layton Aging & Alzheimer's Disease Center worked in collaboration with ORPRN to implement the intervention. Eighteen clinicians and 26 medical assistants in six rural practices in western Oregon participated in the intervention. Using a convenience sample, we recruited practices of varying size, with the proportion of elderly patients in their patient profiles ranging from 6% to 25%, a mix of electronic medical records versus paper medical charts, and both private and publically funded practices. IRB approval was obtained and all study clinicians and MAs signed informed consent.

To facilitate implementation of the intervention, we engaged ORPRNs Practice Enhancement & Research Coordinator (PERC). The PERC served as a liaison between the practices and the research team, assisted practices when difficulties arose in implementing the intervention, and kept an eye on adherence to the protocol and the project timeline.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of a memory screen administered by a medical assistant and, for patients who screened positive for possible dementia, a memory evaluation by the clinician. Patients were screened over a three-month period with an additional two months allowed for memory evaluation by the clinicians for positive screens. Given the short time frame for this study, we did not address management of dementia for diagnosed patients; however, handout materials were provided for clinicians to give patients or family members of persons diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment impaired. We included medical assistant concern as a possible indicator because we theorized that medical assistants might be aware of a patient's memory problems, for example, if the patient appeared confused about their appointment schedule or had problems with medication instructions.

Memory evaluation by clinician

The Memory Evaluation form was provided to the clinicians for use with patients who screened positive. In addition to the single-page Memory Evaluation form, clinicians were provided with tools and instructions for completing the recommended tests. The memory evaluation included tests for five domains of cognitive function (memory, executive function, abstraction, construction ability, and verbal fluency) (25): Mental or dementia.

The “Memory Screen” included four indicators of possible dementia

First, patients were asked if they had noticed a change in their memory that concerned them. Second, if a family member or other informant was present, this person was asked if he/she had noticed a change in the patient's memory that concerned him/her. Although these two questions have not been formally tested for sensitivity and specificity, patient and family concerns about changes in memory are an important component of the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and dementia (23). The third item in the memory screen was Three Word Recall (24). Prior to taking vital signs, the patient was asked to remember the words, “pony”, “quarter”, and “orange”; the patient's vital signs were recorded; and then the patient was asked to recall the three words. Failing to recall ≥2 words on the Three Word Recall was considered positive. Finally, the memory screen form included a place for the medical assistant to check if he or she was concerned that the patient was cognitively

Status Examination, abstraction and judgment questions, Clock Drawing test (26), and verbal fluency (27). We also provided an Activities of Daily Living/Independent Activities of Daily Living scale (ADL/IADLs) (28), the “Get up and Go” test (29), the Geriatric Depression Scale (30), and the Caregiver Burden Assessment (31). These tests are consistent with quality indicators (32) and aided clinicians in recognizing alternative diagnoses and family needs. Instructions for the neurologic exam, and lab and imaging tests (10) were provided in the training and included on the Memory Evaluation form. In addition, clinicians were provided print materials on the following: prescribing for cognitive and psychiatric symptoms, driving assessment, referral cards for the Alzheimer's Association, and other information sheets for caregivers.

Training

Study clinicians, medical assistants, nurses, and front office staff participated in a 2-hour training on recognition and diagnosis of dementia, principles of dementia care management, information on community resources, and the intervention protocol. The training was presented by the study geriatrician (EE), the director of the Alzheimer's Association Oregon Chapter, and the PI (LB) via web conference (one-way PowerPoint presentation and two-way audio). Each practice receiving the web conference training had on-site support from a member of the ORPRN staff to ensure smooth operation of the video equipment. The training was audio taped and distributed to clinicians and staff for later review.

Intervention protocol

For the three-month period of the intervention, all patients 75 and older seen by a study clinician were eligible for screening. If the patient was determined by the medical assistant to have a prior diagnosis of dementia, to have been prescribed dementia medications, or to be “too ill” to be screened, these were noted on the memory screen form and it was placed in the box of completed forms. If these were not the case, the memory screen process was explained to the patient at the time he or she was escorted from the clinic waiting room to the examining room. If a family member was present, he or she was invited to accompany the patient for the first part of the visit. If the patient refused the screen, this was recorded on the form and the form was placed in the collection box. If one or more of the 4 screen indicators was positive, the Memory Screen Form and the Memory Evaluation form were placed on the patient's chart to alert the clinician of the need for a memory evaluation. The memory evaluation could be completed either at that visit or at a separately scheduled visit. For patients who screened positive, we collected data on workups carried out during the next two months following the end of the screening period.

Intervention Evaluation

Outcomes of interest included change in clinician confidence and comfort in diagnosing and managing dementia and changes in the incident diagnosis of dementia. Additionally, we evaluated the adherence to the intervention protocol; and patient, medical assistant, and clinician response to the intervention.

Pre-intervention chart review

To compare the intervention with pre-intervention practice, records from patients aged 75 or older who were seen by study clinicians during a two- to four-week period in October 2006 were reviewed for incident dementia diagnosis over the next 4 months. The number of patient charts reviewed per clinic ranged from 24 to 67 (total of 310 charts).

Dementia Care Confidence Scale (DCCS)

The DCCS is an 8-item scale clinicians to rate their confidence level in assessing and diagnosing dementia, treating symptoms, managing care, differentiating delirium from dementia, differentiating depression from dementia, advising patients and family about community resources, and comfort in disclosing a diagnosis of dementia to a patient and family (33). We administered the DCCS as part of a written survey completed by study clinicians before and after the intervention.

Patient satisfaction surveys

Patients were asked by the medical assistant to complete a brief written satisfaction survey immediately after they were screened. The patient survey asked if they had any concerns about the screening and if, in general, they thought it was a good idea for PCPs to assess older patients' memory and thinking. Patients were also invited in the survey to explain any discomfort they experienced and if there was anything that could be done differently in the screening.

Feedback sessions and surveys of clinicians and practice staff

We surveyed clinicians about their response to the ROAM intervention and conducted feedback sessions in each practice with the clinicians and practice staff who participated in the intervention. Post-intervention sessions were audiotaped and transcribed.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to report the uptake of the intervention. We compared the proportion of dementia-related diagnoses for eligible patients made during the intervention with the proportion of dementia-related diagnoses made for eligible patients in the pre-intervention period covered in the chart review. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Tests were used to compare change in clinician confidence in dementia diagnosis and management before and after the intervention. We used chi-square analysis to assess the effect of gender and age on the proportion of screened patients with positive screens, with Mantel-Haenszel statistic to test for linear effect of age on positive screens. The post-intervention clinician survey and group feedback session transcripts were reviewed by co-authors to gain insight into clinician and medical assistant satisfaction with the intervention and to assess the feasibility of the protocol.

Results

Participation

Eighteen clinicians (11 family practice physicians, 1 internal medicine physician, 4 physician assistants, and 2 nurse practitioners) and 26 medical assistants participated in the study.

Intervention process

Patient screening

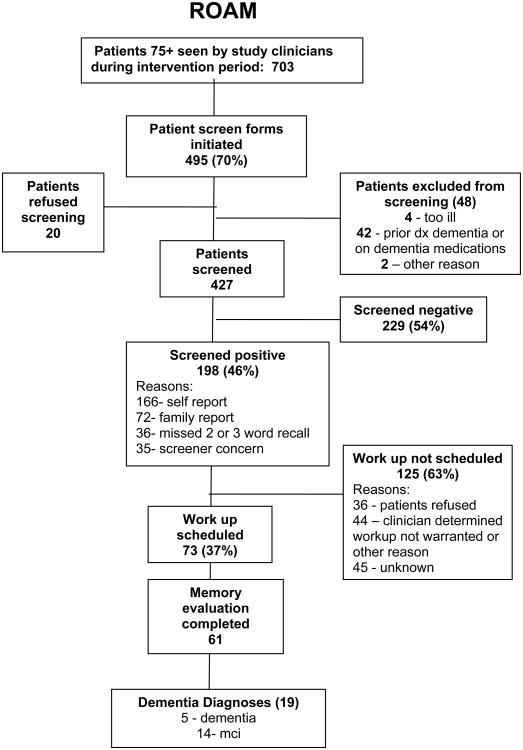

Seven hundred three patients 75 or older were seen by study clinicians during the intervention period (Figure 1). Of the 703 patients 75 or older who were seen by participating clinicians during the intervention period, medical assistants initiated a screen form for 495 patients (70% of the eligible patients). Of the 427 patients who were given the 4-component screen, 198 (46%) screened positive. Ninety-seven screened patients (23%) were accompanied by a family member. Of these, 72 family members (74%) reported concerns about the patient's memory. As expected, older patients were more likely to screen positive (chi-square, p=.001, with a highly significant linear trend (Mantel-Haenszel test, p<.0001)). There was no significant difference in gender between the positive and negative screens.

Figure 1. Intervention Protocol.

Of the patients who screened positive, 73 (37%) had “workup scheduled” checked on the screen form. For the four indicators of possible dementia, the proportion of patients who screened positive who were scheduled for memory evaluation were as follows: three-word recall: 39%; patient report: 37%; family report: 43%; and screener (medical assistant) concern: 77%. Medical assistant concern was the only screen item that had a significant association with “workup scheduled” checked (chi sq p<.0001). For the 125 patients with “workup scheduled” not checked, in 45 cases, no reason was given. For the others, the clinician wrote that the patient refused a memory evaluation (n=36), or that the memory evaluation was not necessary (n=39), or gave other reasons for not scheduling a memory evaluation (n=4). Twenty patients (4%) who were offered the screen refused and 36 (18%) patients with a positive screen refused a diagnostic evaluation.

Dementia Evaluations

Sixty-one patients received a clinical evaluation for dementia, which was carried out in a separate 30-40 minute visit.

Outcomes

Dementia diagnosis

The patients included in the pre-intervention chart review and those seen during the intervention were comparable with respect to age and gender. For the 310 pre-intervention charts reviewed, a total of 3 patients (0.97%) had a recorded new diagnosis of dementia (n = 2) or MCI (n = 1). Among the 703 eligible patients seen during the intervention period, a total of 19 (2.7%) were newly diagnosed with dementia (n = 5) or MCI (n = 14)(p=.06 for difference between groups). With respect to change in clinician confidence and comfort in diagnosing and managing dementia, all 18 clinicians completed the DCCS, and there was a significant improvement in confidence in differentiating depression and dementia (p=0.01). We also found trends in improvement in clinicians' confidence in differentiating delirium and dementia, in treating the symptoms of dementia, and in clinicians' comfort in disclosing the diagnosis to the patient (p-values from 0.06 to 0.10).

Response to intervention

Patient response to screening

Three hundred twenty-five (76%) screened patients completed the survey to assess their response to screening. Ninety-eight percent of respondents reported no concerns or that they were “pleased to have [their] memory evaluated.” No patients reported that they were “a lot uncomfortable” with the memory screening. Ninety-one percent responded that, in general, memory evaluation for older patients was a good idea.

Clinician Response to Intervention: Survey Results

All study clinicians completed the post-intervention survey and all rated the ROAM project as moderately or highly successful in increasing the identification of dementia, in increasing their knowledge about dementia diagnosis, and in their overall assessment of the intervention. Clinicians commented positively on knowledge gained and on the materials provided. Some wrote that they appreciated the opportunity for focused time to address a single issue and for communication with patients about dementia. A number of clinicians reported a desire for further training about the diagnostic protocol and interpretation of the diagnostic tests.

Feedback group results

The clinicians spoke highly of the CME training, the ease in which the screening process was implemented in their clinics, and the quality of the materials provided by the project. As in the written survey, some clinicians reported that they would have liked more training on interpretation of cognitive tests used in the diagnostic workup. A number of the clinicians and medical assistants commented on their surprise that the patients responded so positively to the screening. The medical assistants also reported that the screening process was easy to incorporate into their routine.

Individual practice differences

Despite the overall positive results from the intervention, substantial differences among the practices in adherence to the intervention protocol affected the outcomes as shown in Table 1. To better understand these variations, we reviewed the transcripts of the feedback sessions and discussed the implementation of the intervention with ORPRN staff. We identified two primary factors that influenced these process variations:

Table 1. Practice level data for intervention protocol.

| Practice ID | (1) No. of participating clinicians | (2) % of patient profile over 75 years* | (3) Patients >75 yrs seen during intervention period (n) | (4) Screen forms initiated n (%)† | (5) Patient screens completed N (%)‡ | (6) Positive screens n (%)§ | (7) Patients scheduled for workup n (%) ║ | (8) Patients evaluated n (%)¶ | (9) Patients diagnosed with dementia# n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 13% | 156 | 134(86%) | 108 (81%) | 68(63%) | 29 (43%) | 28(97%) | 7(10%) |

| B | 2 | 20% | 152 | 96(63%) | 82 (84%) | 33(40%) | 5 (15%) | 3(60%) | 2(6%) |

| C | 2 | 9% | 96 | 87(91%) | 77 (88%) | 40(52%) | 8 (20%) | 7 (88%) | 2(5%) |

| D | 3 | 25% | 88 | 83(94%) | 77 (93%) | 30(39%) | 15 (50%) | 12 (80%) | 6(20%) |

| E | 2 | 10% | 73 | 50(68%) | 43 (86%) | 12(28%) | 10 (83%) | 9 (90%) | 3(25%) |

| F | 6 | 6% | 138 | 45(33%) | 40 (89%) | 15(38%) | 6 (40%) | 2 (33%) | 0(0%) |

| Total (N=18) | 18 | n/a | 703 | 495 (70%) | 427 (86%) | 198 | 73 (37%) | 61 (83%) | 19 (9.6%) |

Percent of patients over 75 for practice overall. Data is from ORPRN survey conducted in 2005, except for Practice #2 who provided this information for this project.

Screen forms initiated (Col.4) refers to screen forms that were partially or fully completed including for patients who refused screening or were excluded from screening for other reasons.

Percent with completed screens of patients who had screen forms initiated.

Percent is among patients for whom screen forms were completed

Patients who had “workup scheduled” written on screen form. Percent is among patients with positive screen.

Percent is for patients with “workup scheduled” written on screen form who received dementia workup.

Percent is among positive screens.

1. Integrating the intervention protocol into clinical routines

Several practices appeared to have set up an effective process for identifying patients eligible for screening (A, C, D, see Column 4) and/or for ensuring that patients identified as needing a memory evaluation actually received one (A, C, D, E, Column 8). Practice F attributed their low proportion of patients screened to their being preoccupied with the implementation of a new electronic medical record. In addition, unlike the others, this practice did not create a centralized system (e.g., using staff at the front desk) to place the screen forms on eligible patients' charts. In Practice B, a participating medical assistant unexpectedly died during the intervention period, understandably interrupting the clinical routine during the early part of the intervention.

A number of start-up issues surfaced at the other practices as well, though these were mainly addressed by the ORPRN research coordinator. For example, in one practice the clinicians and assistants initially presented the screening as an option, i.e., they asked the patient if they would like to be screened (opt in) rather than presenting the screening as part of the routine with the opportunity for patients to refuse (opt out).

Another challenge in integrating the intervention into the practice routine was the allocation of time for training. Clinicians requested shortened training and resisted scheduling more than one training session. Nonetheless, a frequent comment following the intervention was the need for additional training.

2. Clinician attitudes

The low proportion of patients scheduled for a memory evaluation among those with positive screens in five of the six practices suggests that the clinicians' attitudes may have influenced adherence to this step in the process. Comments made by clinicians with a low percentage of evaluations support this:

“I would have to say this: I wonder really is diagnosing Alzheimer's really that big a problem. I mean, how many [patients] do you come up with where you had no idea, you had no suspect (sic) that this person had a problem…. I've never seen [medications] be very efficient.”

“ …it would be a lot easier to get enthused about a project that may have more medical relevance. Something that you might really get jazzed about.”

These comments are in contrast to those made by clinicians from practices with higher proportions of positive screens scheduled for diagnostic workup:

“I thought the study was very useful because it identified patients that I was not aware of that had problems, whether it was Alzheimer's or depression or other memory problems.” “I tend to think that the earlier [diagnosis] the better because it helps you think about your patient. It helps you think about their compliance, and helps you think down the road, what are we going to do, and it helps you get the family involved.”

Additionally, in some cases, the clinicians apparently misapplied the results of the delayed 3-word recall: if the person passed this brief memory test but the patient reported concerns about their memory, the clinician often discounted the patient's concerns and opted to not schedule a diagnostic evaluation.

Discussion

This feasibility study was, to our knowledge, the first application of the ACOVE model for screening and diagnosing dementia in rural primary care. We found that the ROAM intervention was easily integrated into the routine patient process by the medical assistants and was well received by patients. For clinicians, there was a more mixed response. Clinicians reported high satisfaction with the training, increased knowledge about dementia, and showed significant increases in confidence in diagnosing dementia; yet, the overall uptake of the intervention was modest and variable across practices, and the clinicians' responses in post-intervention assessments were mixed. The modest outcomes of the proportion of patients diagnosed with dementia may have been affected by these variations.

A major finding of this study was the reluctance of the clinicians to follow up on a positive dementia screen. Clinicians often determined that the symptoms did not warrant a dementia workup. While better training may have increased the proportion of patients with a positive screen who received a memory evaluation, a similar lack of follow-up on a positive dementia screen has been reported by other researchers (16) suggesting that other factors may be at work. The lack of perceived benefit of diagnosing dementia by some clinicians undoubtedly influenced their decision whether or not to schedule a memory evaluation. Other possible reasons for lack of follow-up might include lack of time, poor reimbursement, large patient volumes, the perceived complexity of the memory evaluation protocol, or lack of clinician comfort and confidence in making a diagnosis; however, these were not discussed in the feedback sessions.

Much of what we learned in this study related to the intensely busy environment in which primary care clinicians practice. Our study offers the following insights:

Distance learning using web-based technologies appears to be a feasible method for training busy rural clinicians and medical assistants. We noted the tendency of the clinicians to resist lengthy training but that once the intervention was under way, clinicians actually expressed a desire for further training. The high proportion of patients with a positive screen who did not receive a dementia evaluation suggests that better training on the value of diagnosis may be warranted. Research is needed to further develop and test modes and content of training as a means to improving adherence to quality practice standards.

The medical assistants played a key role in this intervention and their positive response suggests that greater attention be given to ways to engage them. Although we did include the medical assistant in our feedback sessions, we did not gather written input from them The increased likelihood that clinicians would schedule a work up for patients when the medical assistant noted a concern about the patient's memory was also intriguing, suggesting high value these clinicians place on their assistants' opinions. We believe, as others have recommended (33), that enhancing the role of medical assistants is a promising approach to improving care for older patients in rural communities. For example, medical assistants could be trained to assist in screening patients, administer cognitive and other tests used in diagnosis, and offer support to family caregivers and access to community resources.

While we successfully screened 70% of eligible patients, we recognize that our screening tool was not ideal. Several recent studies using different dementia screening instruments have reported higher sensitivity and specificity (3, 16). We chose our tool to ensure that it could be feasibly administered by medical assistants during a busy clinic, but would recommend a screening instrument with higher specificity and validity for use in primary care, such as the Mini-Cog (34) in future research. Another approach that merits consideration is the two-stage screening process used by Boustani et al. (3). Our screen was similar to the first-stage screen used in this study and had a similar proportion of positive screens (43% compared with 46%). With the addition of a 2nd-stage, more sensitive 28-item screen, 13% in the Boustani et al. study were referred for diagnostic evaluation. Adding this screen would have increased the time demand on the medical assistant but could reduce the false positive screens.

To ensure maximum participation and minimum disruption of practice routines, on-site assistance from research staff is essential. The ORPRN Practice Enhancement Research Coordinator was instrumental at the start of the intervention when the practices were becoming comfortable with the intervention protocol and incorporating it into their clinical process. The research coordinator had good access to most of the clinicians and medical assistants when she visited the practices and this facilitated the intervention process. The intervention uptake would likely have also been improved by delaying formal data collection for a week or two after the intervention began.

Limitations and future research

This study is one of the few attempts to test a way to improve the identification of persons with dementia in rural primary care. Its limitations are its small size, that it was not randomized, and its short time frame. In addition to implementing a larger, randomized treatment-control intervention, in future research it will be important to identify a screening tool with better sensitivity and specificity than the one used in this study and to refine the processes for the diagnostic evaluation. The strengths of this study were that it was relatively easily integrated into the routines of the practices in which it was tested, that it resulted in high rates of screening and that patients responded very positively. In those situations where there were procedural glitches needing to be ironed out before the intervention could move forward smoothly, the ORPRN PERC provided essential assistance.

Further research is needed to address the challenges in implementing practice change in rural practices as well as in addressing the barriers to improving the recognition and diagnosis of dementia. Improving rural practice is especially challenging due to limited resources within the practice and in the community where they are located. As other researchers have emphasized (35), practice-based researchers must find the balance between stringent adherence to research protocol and the accommodation of variations in the practice's time, staffing resources, and clinician commitment.

Changing practice related to dementia diagnosis has its own challenges. The low rate of dementia workup found in this and other studies (16) for patients who screened positive for possible dementia needs to be better understood and strategies to overcome this are needed. The lack of follow-through on positive dementia screens may reflect time pressures on clinicians and staff, concerns about reimbursement for visits, and/or uncertainty about the appropriate procedures for the diagnostic workup. Alternatively, it may be due to clinicians' perceptions that dementia diagnosis is of limited benefit until more effective treatments are available. The mixed response of clinicians to this intervention should be viewed against the positive response of patients who overwhelmingly reported their appreciation about being screened and of the medical assistants who played a largely positive and supportive role in its implementation. This study demonstrated the complex issues that must be addressed in implementing dementia screening in rural primary care. The challenges of practice-change in busy rural practices are substantial. Understanding and accommodating the resources available to primary care practices and the attitudes and practices of clinicians are essential if we hope to develop interventions that will be accepted in real world settings.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants R03 HS016007-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality; P30 AGO08017 (Oregon Alzheimer's Disease Center) from NIA; the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI), UL1 RR024140 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

We would like to thank the clinicians, clinic staff, patients and family members who made this study possible.

References

- 1.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: The Aging, Demographics and Memory Study. Neuroepid. 2007;29:125–132. doi: 10.1159/000109998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boise L, Neal M, Kaye J. Dementia assessment in primary care: Results from a study in three managed care systems. J Gerontology: Med Sci. 2004;59(6):621–26. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.6.m621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unversagt FW, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Tierney WM. Documentation and evaluation of cognitive impairment in elderly primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:422–429. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camicioli R, Willert P, Lear J, et al. Dementia in rural primary care practices in Lake County, Oregon. J Geriatr Psych Neurol. 2000;13:87–92. doi: 10.1177/089198870001300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boise, Camicioli R, Morgan DL, Rose JH, Congleton L, et al. Diagnosing dementia: Perspectives of primary care physicians. The Gerontologist. 1999;39(4):457–464. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang Time allocation in primary care offices. Health Services Res. 2007;42(5) doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [Accessed August 31, 2009];Screening for dementia. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/dementia/dementrr.htm.

- 9.Freter S, Bergman H, Gold S, Chertkow H, Clarfield AM. Prevalence of potentially reversible dementia and actual reversibility in a memory clinic cohort. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;159:657–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. Practice parameter: Diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review) Neur. 2001;56:1143–1153. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warshaw GA. Alzheimer's disease: General medical care. Primary Psychiatry. 1996 Nov;:42–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gwyther LP. Family issues in dementia: finding a new normal. Neurol Clin. 2000;18:993–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royall DR, Cordes J, Polk M. Executive control and the comprehension of medical information by elderly retirees. Exp Aging Res. 1997;23:301313. doi: 10.1080/03610739708254033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salas M, In't Veld BA, van der Linden PD, Hofman A, Breteler M, Stricker BH. Impaired cognitive function and compliance with antihypertensive drugs in elderly: the Rotterdam study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70:561–566. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.119812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinclair AJ, Girlin AJ, Bayer AJ. Cognitive dysfunction in older subjects with diabetes mellitus: impact on diabetes self-management and use of care services. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;50:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borson S, Scanlan J, Hummel J, Gibbs K, Lessig M, Zuhr E. Implementing routine cognitive screening on older adults in primary care: Process and impact on physician behavior. JGIM. 2007;22:811–817. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuben DA, Roth C, Kamberg C, Wenger NS. Restructuring primary care practices to manage geriatric syndromes: The ACOVE-2 intervention. JAGS. 2003;51:1787–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weeks WB, Wallace AE. Rural-urban differences in primary care physicians' practice patterns, characteristics, and incomes. Jl Rural Hlth. 2008;24(2):161–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fordyce MA, Chen FM, Doescher MP, Hart LG. Final Report # 116. Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington School of Medicine; 2005. physician supply and distribution in rural areas of the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cifuentes M, Fernald DH, Green LA, et al. Prescription for health: Changing primary care practice to foster healthy behaviors. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(Suppl):S4–S12. doi: 10.1370/afm.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tierney WM, Oppenheimer CC, Hudson BL, et al. A national survey of primary care practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:242–250. doi: 10.1370/afm.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nutting PA, et al. Initial Lessons from the First National Demonstration Project on Practice Transformation to a Patient–Centered Medical Home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:254–260. doi: 10.1370/afm.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldman HH, Jacova C, Robillard A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia:2. Diagnosis CMAJ. 2008;178(7):825–836. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandler MJ, Lacritz LH, Cicerello AR, et al. Three-word recall in normal aging. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26(8):1128–1133. doi: 10.1080/13803390490515540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiernan RJ, Mueller J, Langton JW, Van Dyke C. The Neurobehavioral cognitive status examination: a brief but quantitative approach to cognitive assessment. Ann Int Med. 1987;107(4):481–485. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-4-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunderland T, et al. Clock drawing in Alzheimer's disease: a novel measure of dementia severity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:730–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurol. 1989;39:1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas VS, Rockwood K, McDowell I. Multidimensionality in instrumental and basic activities of daily living. Jl of Clin Epid. 1998;51(4):315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podsiadlo D, Richardosn S. The time up and go: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly people. JAGS. 1991;9:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheikh JL, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, editor. Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention. Vol. 1986. New York: Haworth press; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois, Lever JA, O'Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerst. 2001;41(5):652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chow TW, MacLean CH. Quality indicators for dementia in vulnerable community-dwelling and hospitalized elders. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(8 Pt 2):668–676. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_part_2-200110161-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meuser TM, Boise L, Morris JC. Clinician beliefs and practices in dementia care: Implications for health educators. Educ Ger. 2005;30:491–516. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The Teamlet Model of Primary Care. Annals of Family Med. 2007;5(5):457–461. doi: 10.1370/afm.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1451–1454. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF, Etz RS, et al. Fidelity versus flexibility. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5S):S381–S389. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]