Abstract

Purpose

Metabolism, and especially glucose uptake, is a key quantitative cell trait that is closely linked to cancer initiation and progression. Therefore, developing high-throughput assays for measuring glucose uptake in cancer cells would be enviable for simultaneous comparisons of multiple cell lines and microenvironmental conditions. This study was designed with two specific aims in mind: the first was to develop and validate a high-throughput screening method for quantitative assessment of glucose uptake in “normal” and tumor cells using the fluorescent 2-deoxyglucose analog 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxyglucose (2-NBDG), and the second was to develop an image-based, quantitative, single-cell assay for measuring glucose uptake using the same probe to dissect the full spectrum of metabolic variability within populations of tumor cells in vitro in higher resolution.

Procedure

The kinetics of population-based glucose uptake was evaluated for MCF10A mammary epithelial and CA1d breast cancer cell lines, using 2-NBDG and a fluorometric microplate reader. Glucose uptake for the same cell lines was also examined at the single-cell level using high-content automated microscopy coupled with semi-automated cell-cytometric image analysis approaches. Statistical treatments were also implemented to analyze intra-population variability.

Results

Our results demonstrate that the high-throughput fluorometric assay using 2-NBDG is a reliable method to assess population-level kinetics of glucose uptake in cell lines in vitro. Similarly, single-cell image-based assays and analyses of 2-NBDG fluorescence proved an effective and accurate means for assessing glucose uptake, which revealed that breast tumor cell lines display intra-population variability that is modulated by growth conditions.

Conclusions

These studies indicate that 2-NBDG can be used to aid in the high-throughput analysis of the influence of chemotherapeutics on glucose uptake in cancer cells.

Keywords: 2-NBDG, Metabolism, High-throughput, Single-cell, Glycolysis

Introduction

The process of aerobic glycolysis (or the “Warburg effect”) has gained a great deal of attention since its discovery by Otto Warburg more than 70 years ago, to eventually become widely accepted as the seventh hallmark of cancer [1, 2]. This process is defined molecularly by a dramatic increase in extracellular glucose consumption accompanied by an elevated rate of lactate excretion, regardless of oxygen abundance [1, 3–5]. This observation is exploited clinically to detect solid tumors based on their increased uptake of the radioactive glucose analog 2-deoxy2-[18F]fluoro-d-glucose (FDG), which can be imaged by positron emission tomography (PET) [6]. Avidity to glucose in tumors is now believed to be fundamental to supporting bioenergetics and biosynthetic demands for uncontrolled proliferation consequent to tumor transformation [4, 7, 8]. Recent studies have uncovered the molecular basis for metabolic alterations responsible for elevated glucose uptake and utilization, providing a more detailed understanding of biological relationships underlying cancer development [9].

In recent years, mounting molecular and histological evidence has clearly indicated that solid tumors are not uniform, but rather biologically heterogeneous entities comprised of diverse cellular types [10, 11]. Clinically, it has become increasingly apparent that this heterogeneity is correlated with metabolic behavior of tumors, as evident from PET images depicting spatial variability in uptake rates of radioactive glucose (e.g., FDG) and thymidine analog [12–15]. Nonetheless, investigating the cellular bases of heterogeneity in tumors is hurdled by the lack of systematic quantitative approaches for measuring glucose metabolism at the single-cell level. Therefore, developing novel high-throughput methods to quantitatively measure glucose uptake in live cells, at both the population and cellular levels, would provide useful screening platforms to evaluate the metabolism of a large number of tumor cells and the effects of various perturbations (e.g., microenvironmental cues, drugs) on cellular metabolism.

In this study, we developed and implemented a high-throughput population-based fluorometric method to evaluate a multitude of kinetic properties of glucose uptake in “normal” and tumor cell lines in vitro using recently developed 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxyglucose (2-NBDG) [16–19]. 2-NBDG, a novel fluorescence glucose analog probe that was initially developed to measure the glucose uptake rates in microorganisms, has proven to be of great utility to also measuring glucose uptake rates in a wide range of non-mammalian and mammalian cells in recent years [16–26]. Several lines of evidence have previously demonstrated the validity of 2-NBDG as a tracer for direct monitoring of glucose transportation in mammalian and non-mammalian cells. For instance, 2-NBDG has shown to be transported intracellularly by the same glucose transporters (GLUTs) as glucose, as evident by competitive inhibition of 2-NBDG by d-glucose and by pharmacological inhibition by GLUTs inhibitors such as cytochalasin B and phloretin in mammalian cells [17, 18, 21, 27, 28]. It has also been shown by mass spectrometry that 2-NBDG undergoes phosphorylation at the C-6 position, a reaction that causes the molecule to be retained within the cell, identical to the mechanism that causes FDG to also be retained [17, 23, 29]. 2-NBDG was also reported to be transported into cells via all of the GLUTs and in several mammalian cells via SGLT1, but the relative affinities of each transporter are still under investigation [25, 30, 31]. More recently, the transportation of 2-NBDG and FDG were reported to present similar affinities both in vitro and in vivo in mammalian cells [32]. However, 2-NBDG represents several other clear advantages over the other available glucose tracers, such as 2-DG or the radiolabel isotope FDG, including its low relative cost, capacity for high temporal and spatial resolution (at the single-cell level), lack of ionizing radiation, and the non-destructive nature allowing direct monitoring of glucose transportation in live cells.

In addition, we developed a second independent approach to directly evaluate the distribution of glucose uptake at the single-cell level that utilizes the power of high-content automated microscopy (HCAM), cell-cytometric image analysis (via CellProfiler) [33], and advanced statistical techniques. Acquiring single-cell quantitative measurements of glucose uptake provides a novel tool for dissecting the variability in metabolic states that exists within a given tumor cell population. We applied this tool to examine the influence of various microenvironmental conditions in modulating the intra-population dynamics of glucose uptake in normal and tumor cells. The versatility of both of our approaches facilitated the simultaneous and direct measurement of 2-NBDG uptake in different cell lines under multitude of extracellular conditions. This capability allows direct and fair comparison among multiple cell types and/or extracellular conditions such as growth factors, nutrient arability, and drug screening as compared to other previously published methods. Taken together, our results clearly demonstrate that both 2-NBDG assays can be used to accurately and reproducibly measure glucose uptake for a range of cell lines in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

MCF10A, a breast mammary epithelia-derived cell line, and its more aggressive, invasive derivative, MCF10A-CA1d (CA1d) [34], were routinely cultured in DMEM/F12 (GIBCO, Auckland, New Zealand), horse serum (5%; GIBCO), cholera toxin (0.1 mg/mL; GIBCO), insulin (1.0 mg/mL; GIBCO), hydrocortisone (0.5 mg/mL; GIBCO), and epidermal growth factor (EGF; 20 ng/mL; GIBCO). The MCF-7 breast cancer cell line [35] and the HepG2 liver cancer cell line [36] were grown either in standard DMEM/Ham’s F12 media supplement with 2 mM l-glutamine, or standard RPMI 1640 media (GIBCO), each with added 10% FBS (GIBCO). All cell lines were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Population-Based Fluorometric Microplate Assays

To evaluate the kinetics of 2-NBDG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) uptake with increasing cell density, MCF10A and CA1d cell lines were seeded (0–30,000 cells/well) in clear-bottomed 96-well microplates (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in triplicate. Cells were allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C (for ~12 h) before performing uptake assays. After overnight incubation, all wells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; GIBCO) and incubated with 2-NBDG (100 µM) for 10 min at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. We stopped the reaction by adding a twofold volume of ice-cold PBS and the wells were washed again with ice-cold PBS three times. The fluorescent signal before (autofluorescence) and after adding 100 µM 2-NBDG was measured using the fluorometric mode of a Victor-3 multi-well plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA; using the 485 nmex and 520 nmemiss filter set). The net increase in fluorescence was normalized to the lowest signal (0 cells/well), which was taken as the ratiometric quantitation of 2-NBDG uptake in cells.

Similarly, 2-NBDG uptake in MCF10A and CA1d cell lines was evaluated by incubating cells (20,000 cells/well) with increasing concentrations of 2-NBDG (0–300 µM). Quantitation was performed as described above.

To test if 2-NBDG is taken up by cells via GLUTs, glucose competitive inhibition assays were performed. Briefly, cells were incubated with 2-NBDG (300 µM) in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of d-glucose (0–10 mM; Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA). 2-NBDG uptake was also inhibited pharmacologically using the glucose inhibitor, Phloretin (MP Biochemicals LLC, Solon, OH, USA). These assays were performed as described above, except cell lines were incubated in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of Phloretin (0–1,000 µM) with final DMSO concentration of 1% v/v.

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Drug Treatments

To test the effects of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors on 2-NBDG uptake, MCF10A and CA1d cell lines were grown in culture (as described in previous “cell culture” section) in clear-bottomed 96-well microplates at 50,000 cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight. The next day growth media were removed from all wells and replaced by fresh growth media containing 0, 10, 100, 1,000, or 10,000 nM Lapatinib at a final concentration of 0.1% v/v in DMSO. Similarly, separate plates were prepared and treated with Erlotinib at the same concentrations. Cells were incubated with drugs for another 24 h under standard culture conditions and the 2-NBDG labeling and measurements were performed as previously described (in “population-level fluorometric microplate assays” section).

Cell Viability Assay

To test the cytotoxic effect of 2-NBDG exposure on cells, 2-NBDG uptake assays were performed as described in the above section, except cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 50,000 cells/well. After exposure to increasing doses of 2-NBDG (0–300 µM), reactions were stopped by addition of ice-cold PBS, followed by 3 washes with PBS. Triplicate wells from each treatment were trypsinized and cell suspensions were incubated with 4% v/v of Trypan Blue solution (Mediatech, Herendon City, VA, USA) in PBS for 5 min. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer, whereby dead (dark blue) and viable cells (transparent) were used to calculate the percent viability ((viable cells/(viable cells+dead cells))×100). For positive control, cells were also exposed to 1% SDS solution for 5 min to induce cell death.

Single-Cell-Based HCAM Assays

To dissect inter- and intra-cell line variability of glucose uptake at the single-cell level, 2-NBDG was used to screen for differences among MCF10A and CA1d cell lines. For all experiments, cells were seeded (20,000 cells/well) in 96-well microplates and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C in tissue culture media. For dose–response assays, cells were washed with PBS buffer three times and 2-NBDG was added at various concentrations (0–300 µM) in PBS. For glucose competitive inhibition assays, cells were treated similarly, except cells were treated with increasing concentrations of d-glucose as described in the above section. Cells were then incubated with 2-NBDG or (d-glucose/2-NBDG) for 10 min at 37° C. The reactions were stopped by addition of ice-cold PBS, followed by three additional washes with PBS. All wells were then immediately imaged using a BD Biosciences Pathway 855 (Rockville, MD). For testing the effect of microenvironmental perturbation on glucose uptake, MCF10A and CA1d cells were cultured under optimal growth condition in the presence of 5% horse serum and other growth supplements (S/S) overnight as described previously in detail (in “cell culture” section). After incubation, cells were washed with serum-free DMEM/F12 medium three times and separate wells for each cell line were replaced with optimal growth medium (S/S), suboptimal medium that contains only basal DMEM-F12 medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL EGF (EGF), or depleted medium containing only basal DMEM/F12 with no serum or supplements added (0/0) and grown for another 12 h in culture. Cells from all three treatments were then labeled similarly with 2-NBDG as described above.

For nuclear labeling, Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) was used after an initial round of 2-NBDG imaging by adding 1:1,000 dilution v/v (in PBS) of the dye and incubated for 5 min. Images were acquired using a BD Pathway imager using a green channel filter set (470 nmex–520 nmemiss) for 2-NBDG and a blue channel set (340 nmex–420 nmemiss) for Hoechst nuclear stain.

Image Analysis

All fluorescence images used for quantitation of 2-NBDG uptake were digitized and stored as TIFF files. Single-cell quantitation of 2-NBDG uptake was assessed as the intracellular accumulation of fluorescence, which was analyzed using open-source image analysis software, CellProfiler [33, 37]. Briefly, illumination correction of fluorescent images was performed using blank and non-labeled images. All experimental images used Hoechst dye nuclear stain as the primary identifier (primary object) for total cell stain and for segmentation purposes. The OTSU adaptive thresholding method and propagation algorithm (from CellProfiler image analysis modules) were used to identify 2-NBDG stain (secondary object). Automated image analyses were performed to obtain a count of primary objects (nuclei), mean intensities of nuclei, a count of secondary objects, and mean intensity of secondary objects (i.e.2-NBDG), and data were exported to Microsoft Excel spreadsheets for further analysis. The mean intensity of 2-NBDG is expressed as intensity in terms of arbitrary fluorescence units (a.f.u.). The percent of 2-NBDG labeled cells that uptake 2-NBDG within a given population was determined as: (the number of cytoplasmic positive cells = total number of cells (nuclear stained ))×100.

Statistical Analysis

All experimental data are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) of n independent measurements (as indicated in each figure legend). All treatments within each experiment were performed in triplicate wells. Statistical analysis was performed using either GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA) or R freeware (http://www.r-project.org). For population-based comparisons, Student's t tests (two-sided, independent) were performed to detect significant differences between treatments, with p values <0.05 accepted as significant (where indicated*). For single-cell-based comparisons, medians and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by bootstrapping (with 3,000 replications).

Results

2-NBDG is Incorporated into Cells in a Density-Dependent Manner

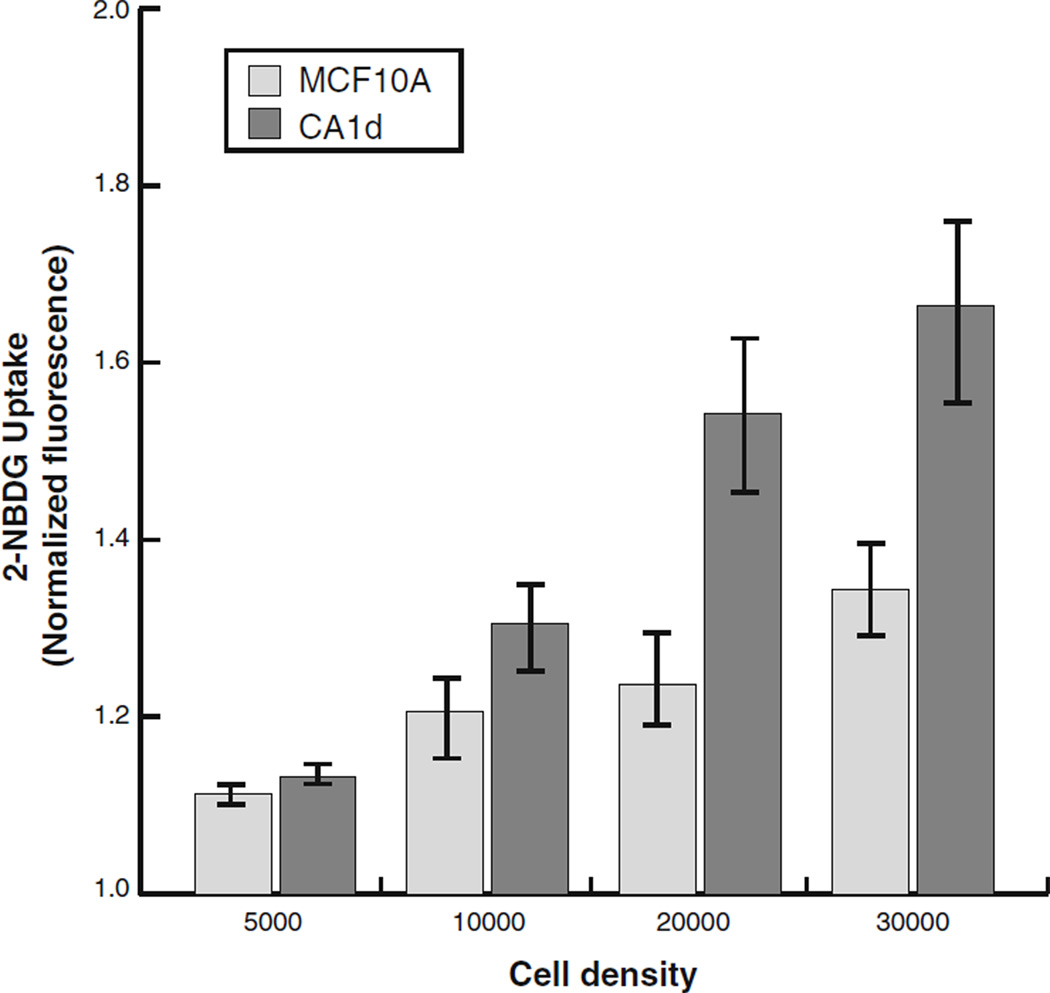

Initial population-based experiments were performed to evaluate the linearity of 2-NBDG uptake in both MCF10A, a nontumorigenic epithelial cell line, and CA1d, a tumorigenic transformed cell line. Cells were seeded at increasing densities (from 0 to 30,000 cells/well), treated with 2-NBDG (100 µM), and incubated for 10 min at 37°C prior to imaging. These results demonstrate that both cell lines exhibited a stepwise increase in 2-NBDG incorporation, directly in line with the number of cells plated (Fig. 1). Of note, CA1d, the aggressive cancer cell line, consistently incorporated more 2-NBDG than MCF10A cells, particularly at higher cell seed densities (as confirmed by microscopic examination of cells in microplates shown in the Electronic Supplementary Material, Online Resource 1).

Fig. 1.

2-NBDG uptake correlates with cell number. Population-level 2-NBDG uptake was quantified using a fluorometric plate reader. MCF10A or CA1d cells were seeded at a range of densities (0–30,000/well) and 2-NBDG (100 µM) was added and allowed to incubate for 10 min prior to stopping reactions. All raw values were normalized to background levels obtained when seeding no cells, and are presented as the mean±SEM of all experiments performed (N=5). Fluorescence levels indicate a linear response of 2-NBDG uptake for both cell lines in a density-dependent manner. CA1d consistently exhibited a higher level of 2-NBDG uptake, although not significantly different than MCF10A cells.

2-NBDG Uptake Occurs in a Dose-Dependent Manner

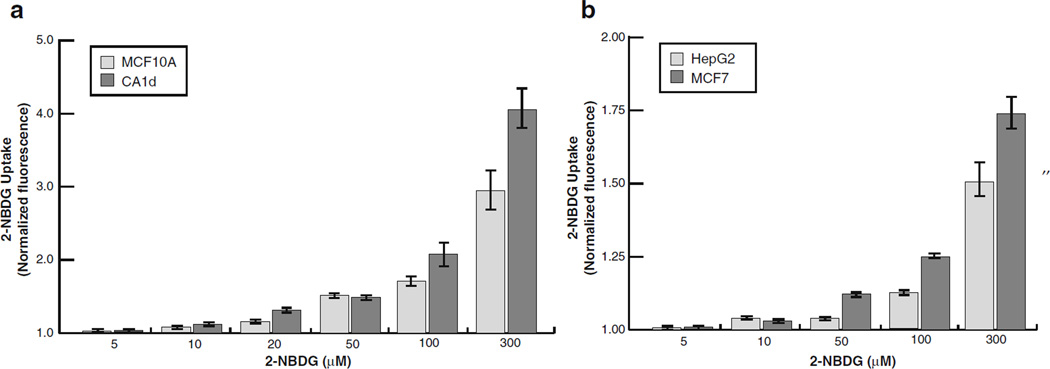

To determine if 2-NBDG uptake occurs in a dose-dependent manner, MCF10A and CA1d cells were treated with increasing concentrations of 2-NBDG concentrations (0–300 µM). As shown in Fig. 2a, bothMCF10A and CA1d cell lines consumed very little 2-NBDG at lower concentrations (0–20 µM); however, at higher concentrations (50–300 µM), both cell lines consumed the probe in a dose-dependent manner. Following treatment with 300 µMof 2-NBDG, the tumorigenic CA1d cell line consumed approximately 1.5-fold more 2-NBDG than nontumorigenic MCF10A epithelial cells. Microscopic examination of MCF10A and CA1d cells confirmed these results (data not shown). Interestingly, a subpopulation of CA1d cells consumed high levels of 2-NBDG even at low concentrations.

Fig. 2.

2-NBDG uptake is dose-dependent. Population-level glucose uptake was quantified in response to increasing doses of 2-NBDG (0–300 µM) using a fluorometric plate reader. All raw values were normalized to background levels obtained for “blank” wells that were treated the same as samples, and are presented as the mean±SEM of all experiments performed. a Both normal MCF10A cells and CA1d cancer cells absorbed 2-NBDG in a dose-dependent manner; not surprisingly, uptake levels were fairly low at low concentrations of the probe, while higher levels of uptake were observed at high concentrations. In summary, CA1d displayed consistently consumed more 2-NBDG than MCF10A (N=5). b Similarly, MCF7 human breast cancer cells and HepG2 human liver carcinoma cell lines exhibited a steady increase in fluorescence signal in a dose-dependent manner (N=3).

To validate that the high-throughput spectroscopic assay is reliable for screening a range of other tumor cell lines, we also analyzed 2-NBDG uptake of MCF7 breast cancer cells and HepG2 human hepatocarcinoma cells, both of which were used previously in cooperation with 2-NBDG and a microscopy-based fluidic-chamber method [38]. As expected, both MCF7 and HepG2 cancer cells also consumed probe in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, these cell lines exhibited 2-NBDG uptake levels consistent with the previously published findings [38]. Taken together, these results confirm that our population-based fluorometric assay can be used to reliably measure 2-NBDG uptake in both normal and tumor cell lines.

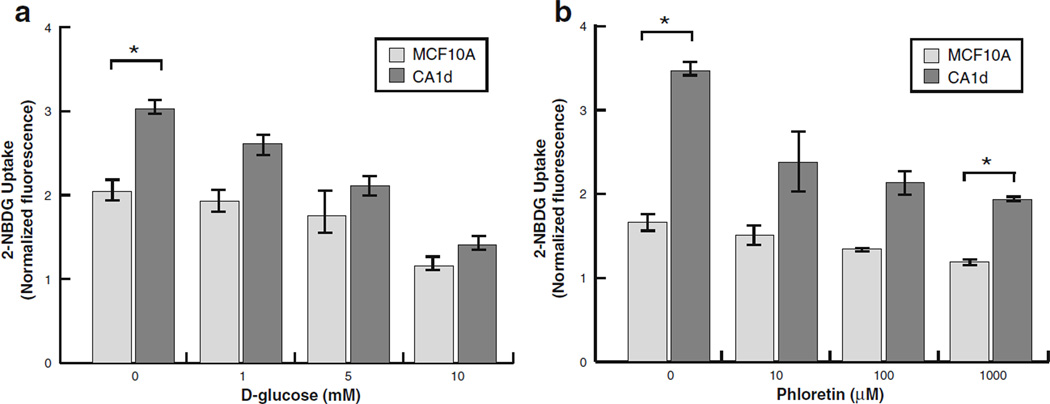

2-NBDG Uptake is Blocked by Competitive Inhibition by d-Glucose and GLUT Inhibitors

To determine if 2-NBDG cellular uptake occurs via GLUT-mediated facilitative diffusion, a competitive glucose inhibition assay was performed. For this assay, 2-NBDG uptake was measured for MCF10A and CA1d cells in the presence of a range of d-glucose (0–10 mM), which is known to compete with 2-NBDG in mammalian cells [38]. As shown in Fig. 3a, 2-NBDG uptake was diminished for both cell lines in a dose response manner with increasing levels of d-glucose. The greatest effect was observed at 10 mM of d-glucose, which was ~2-fold less than the values measured for respective cell lines in the absence of d-glucose.

Fig. 3.

d-Glucose and Phloretin inhibit 2-NBDG uptake. a To determine if 2-NBDG uptake is specific to GLUTs for MCF10A and CA1d cells, population-level 2-NBDG uptake was assessed in the presence of increasing doses of d-glucose (0–10 mM). All raw values were normalized to background levels obtained for “blank” wells that were treated the same as samples, and the data are presented as the mean±SEM of all experiments performed (N=3). Both cell lines exhibited a steady decrease in 2-NBDG uptake in response to increasing d-glucose concentration. *P<0.05, significant differences. b Specificity to transportation via GLUTs was also validated by pharmacological inhibition of 2-NBDG uptake by Phloretin (0–1,000 µM; N=3). Similarly, both cell lines exhibited a steady decrease in 2-NBDG uptake in response to increasing Phloretin concentrations. *P<0.05, significant differences.

To confirm these results, 2-NBDG uptake was also blocked for MCF10A and CA1d cells pharmacologically using Phloretin, a glucose transport inhibitor [39–41]. As shown in Fig. 3b, Phloretin treatment (0–1,000 µM) inhibited 2-NBDG uptake in both cell lines in a dose-dependent manner. Of note, this inhibition was much more pronounced for CA1d than MCF10A. The incomplete inhibition of 2-NBDG uptake by d-glucose competition, even at high millimolar concentrations or pharmacologically by Phloretin, is consistent with the reported kinetics of 2-NBDG, which binds with far higher affinity to GLUTs than its natural counterpart d-glucose [42]. Collectively, these data clearly indicate that 2-NBDG is mainly transported by facilitative diffusion via GLUTs, consistent with previously published reports [16–20, 22].

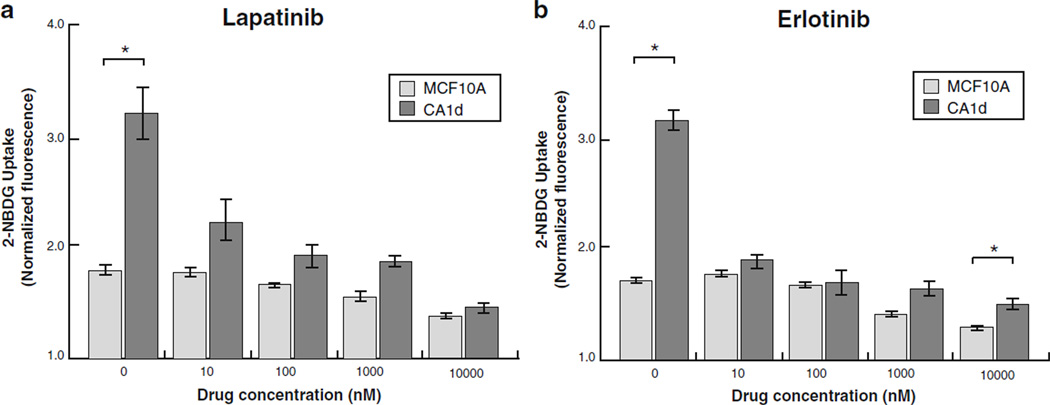

2-NBDG Uptake is Reduced by Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

To assess the validity of our method as high-throughput platform for drug screening, MCF10A and CA1d were treated with increasing doses of two different classes of small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors Lapatinib and Erlotinib [43]. As shown in Fig. 4a, b, our results clearly demonstrate a direct decrease in 2-NBDG uptake in both cell lines in response to increasing doses of Lapatinib and Erlotinib. For CA1d in particular, an immediate and obvious drop was observed in 2-NBDG uptake at 10 nM treatment of either drug. Of note, the most significant inhibition of both receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors was observed at 10 nM, with higher doses of both drugs resulting in more gradual decreases in 2-NBDG uptake. These data demonstrate the utility of our method for conducting rapid and robust drug screening in multiple cell lines using multiple drug doses and classes.

Fig. 4.

Receptor tyrosine kinase small molecule inhibitors reduce 2-NBDG uptake. a Treatment of MCF10A and CA1d with a Lapatinib or b Erlotinib for 24 h resulted in reduction of 2-NBDG uptake in both cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (N=3). CA1d showed more pronounced decrease at concentrations of ≥10 nM compared to MCF10A. *P<0.05, significant differences.

Short-Term Exposure of 2-NBDG is Not Cytotoxic

Since 2-NBDG is a deoxyglucose analog that cannot be metabolized by normal glycolytic enzymes, it can potentially elicit cytotoxic effects by depleting the level of intracellular glucose available to cells [16]. Therefore, to evaluate the cytotoxicity of 2-NBDG uptake during the time window of our assay (10 min), viability of MCF10A and CA1d cell lines was examined in the presence of the range of 2-NBDG concentrations employed in experiments thus far. As shown in the Electronic Supplementary Material, Online Resource 2, in contrast to 1% SDS treatment, none of the concentrations of 2-NBDG tested has a cytotoxic effect on either cell line.

2-NBDG Uptake is Variable Within Cell Line Populations

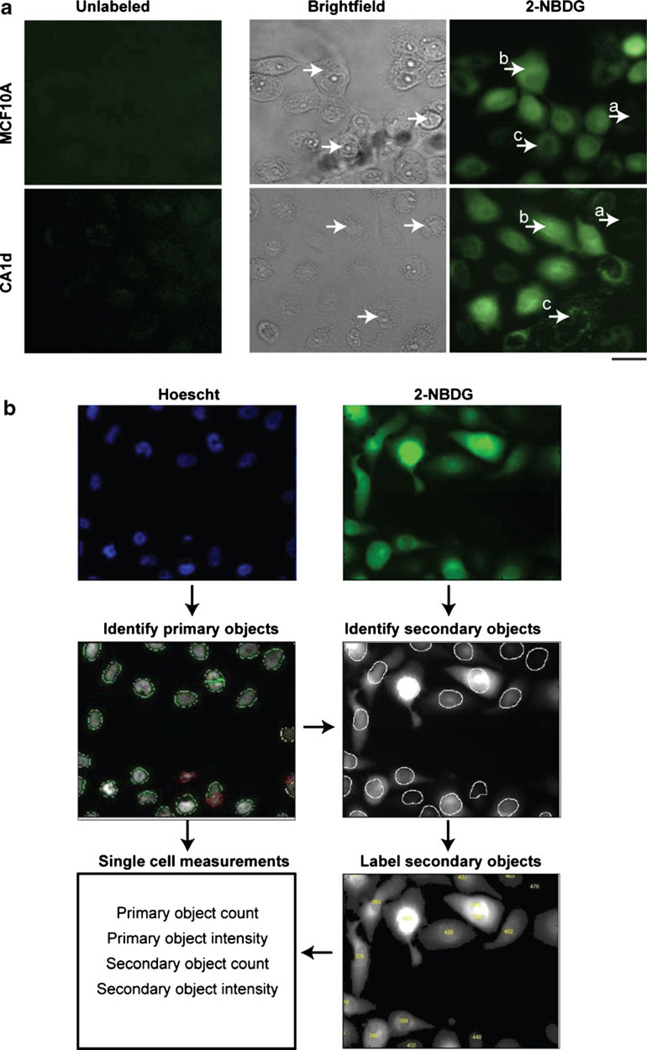

To examine underlying population dynamics of 2-NBDG uptake in MCF10A and CA1d, microscopic images of unlabeled and 2-NBDG-treated single cells were observed. As shown in the fluorescent images of Fig. 5a, 2-NBDG displayed a range of morphological patterns and staining intensities at both the cellular and subcellular levels in both cell lines. Within each population of cells, at least three distinct staining patterns, or cell subsets, were observed: firstly, some cells remained altogether unstained (a), the second type includes cells with diffusive staining (b), and the third type of cells includes cells with punctate morphology patterns (c). Of note, the most common feature of 2-NBDG labeled cells is the increased intensity of 2-NBDG in the perinuclear area, which is consistent with previously published reports [21, 22]. The heterogeneity of the subcellular distribution of 2-NBDG staining we observed in breast cancer cell lines is somewhat similar to that reported by another group in HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cell lines, which the authors attributed to the integration of 2-NBDG monomers in de novo synthesized glycogen in these cells [44]. This suggests the possible integration of 2-NBDG in multiple subcelluar locations and/or metabolic pathways, depending on cell type.

Fig. 5.

Single-cell 2-NBDG uptake is variable within cell line populations. a Representative microscopic images of MCF10A and CA1d are shown. Images include from left to right: unlabeled cells (fluorescent channel) and 2-NBDG-labeled cells (both brightfield and fluorescent channels). Both cell lines displayed intra-population variability of 2-NBDG uptake, both at cellular and sub cellular levels. From inspection of images, three patterns of labeling can be seen: 1) cells with no label (fluorescence), 2, diffusively stained cells which were the most predominate pattern in MCF10A and third, locally punctuate pattern that was abundantly detected in CA1d to less extinct in MCF10A (see bottom arrows in CA1d after adding 2-NBDG). b Schematic of image processing workflow for single-cell analysis using CellProfiler. Briefly original fluorescence images were exported as a pair of Hoechst stained nuclei (blue) and 2-NBDG stained cells (green). Hoechst staining was used to identify primary objects (nuclei). Once the primary objects were identified, the OTSU adaptive propagation software was used to identify 2-NBDG labeled cell bodies (secondary objects). Images were used to extract cell measurements, including: nuclei count, nuclei intensity, 2-NBDG labeled cell count, 2-NBDG intensity. 2-NBDG was used as a quantifier of glucose uptake per cell (in a.f.u.), and other measurements were used to calculate the percentage of cells that were 2-NBDG labeled (based on 2-NBDG count) out of total cells (based on nuclei count). All extracted data generated were exported to Excel spreadsheets for analysis.

Single-Cell HCAM Experiments Reveal Variability in 2-NBDG Uptake

Initial inspection of 2-NBDG labeled cells using fluorescence microscopy revealed obvious variability across cells within a single population. Therefore, we devised an alternative quantitative single-cell strategy to determine the full spectrum of 2-NBDG uptake distribution within a given population of cells. For this approach, MCF10A and CA1d cells were doubly labeled with both 2-NBDG and Hoechst staining, a nuclear stain, and examined by HCAM coupled with the automated image analysis platform, CellProfiler [37]. In these experiments, Hoechst staining provides a mean for obtaining a total cell count for each microplate well and can be used for identification of the percentage of cells labeled with 2-NBDG (areas positive for Hoechst staining signal, but negative for 2-NBDG signal). A summarized schematic of our image analysis workflow is shown in Fig. 5b.

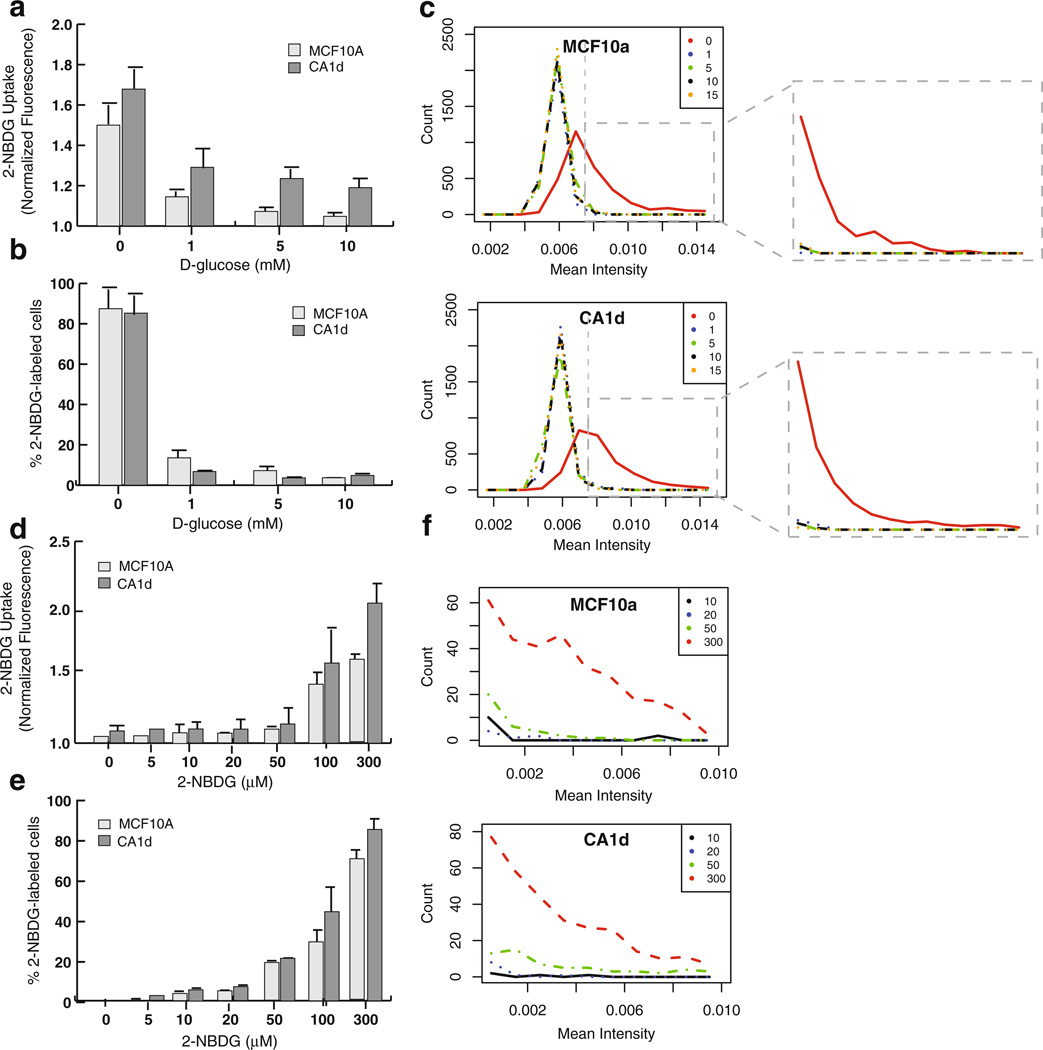

Use of HCAM for average population-based measurements studies of glucose competition (Fig. 6a) 2-NBDG dose–response uptake (Fig. 6d) for MCF10A and CA1d cells revealed data consistent with our earlier fluorometric microplate assays (Figs. 3a and 2a, respectively). However, single-cell image analysis revealed differences between MCF10A and CA1d cell lines in terms of the percentage of 2-NBDG labeled cells both after competitive inhibition with increasing concentrations of d-glucose and across different doses of 2-NBDG (Fig. 6b, e). Specifically, while MCF10A cells showed a slightly higher percentage of 2-NBDG labeled cells when competitively inhibited with increasing doses of d-glucose (Fig. 6b), the opposite trend was observed in tumorigenic CA1d that displayed a higher percentage of cells with increased levels of glucose analog incorporation compared to the nontumorigenic MCF10A at almost every 2-NBDG dose tested (Fig. 6e). These data indicate that cells within a given population are metabolically variable and that at least two or more metabolically distinct subpopulations can be teased out by our assays. The distribution spectra of single-cell 2-NBDG uptake for MCF10A and CA1d cell populations acquired by HCAM further confirmed the existence of two or more metabolically distinctive subpopulations of cells (Fig. 6c, f). Altogether, these results suggest that intra-population cell-to-cell variability exists both within MCF10A and CA1d cell lines, at least in terms of incorporation of 2-NBDG.

Fig. 6.

Single-cell-based HCAM experiments reveal variability in 2-NBDG uptake. Average population-level data were obtained by taking the average image intensity (a.f.u.) of 2-NBDG (green channel) with increasing doses of 2-NBDG, data for glucose competition and dose–response (a, d, respectively) the data are presented as the mean±SEM of all experiments performed (N=3). The percentage of 2-NBDG-labeled cells for d-glucose competitive inhibition assay (b) and dose–response studies (e) were analyzed using HCAM single-cell assay. c The distribution of single-cell uptake measurements expressed as mean intensity/cell in MCF10A and CA1d cell populations for glucose competition assay are shown, the data are representative of two independent trials. Auto fluorescence background was excluded from the raw data by applying threshold value (gray dotted line) that correspond to non-labeled cell controls as illustrated by sub-window (c) for MCF10 A and CA1d cell populations. f The single-cell distribution of 2-NBDG uptake in dose–response assay after background correction.

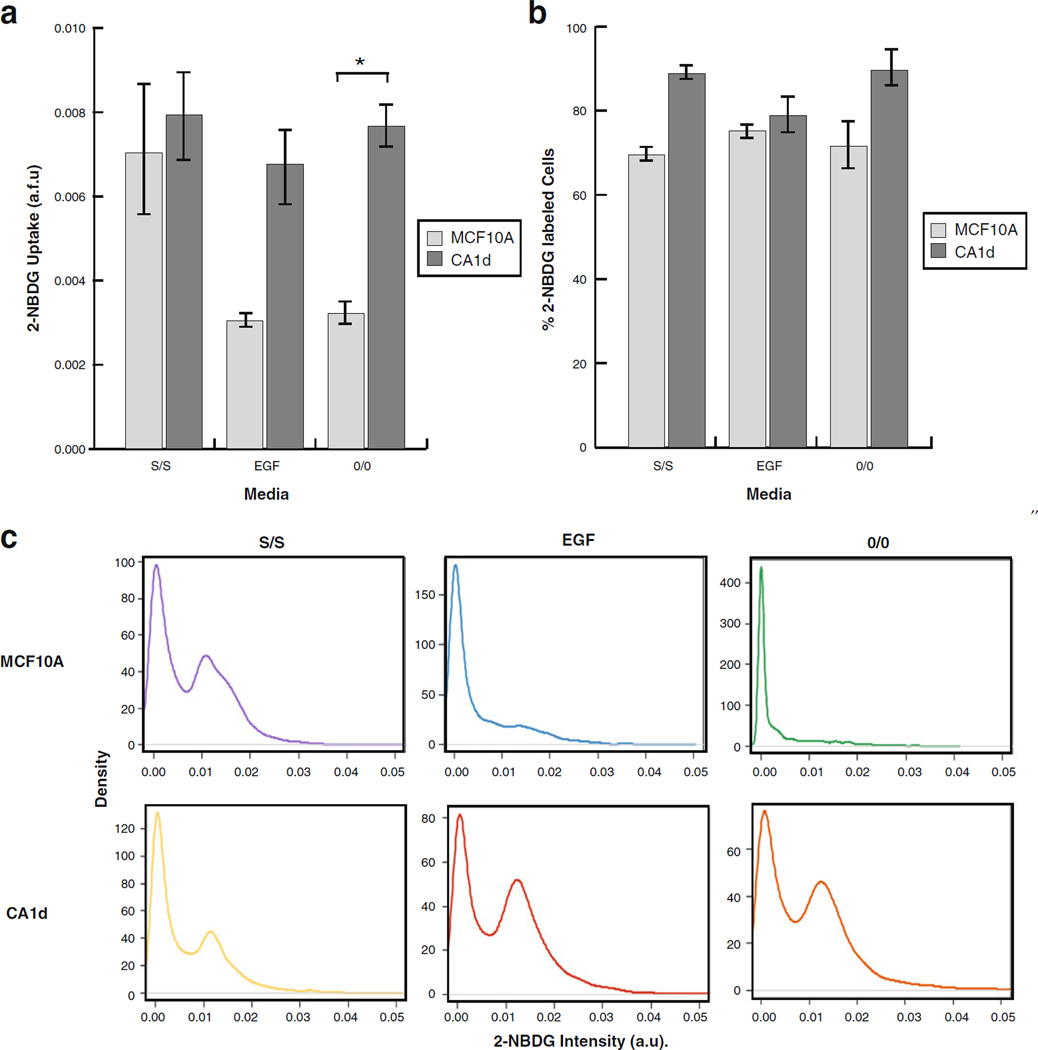

Intra-population Variability of Tumorigenic CA1d Cell Line is Modulated by Growth Conditions

To determine the relevance of our newly developed single-cell analysis application to monitor and detect changes in cellular glucose analog uptake in response to physiological stimuli, we tested if the perturbation of microenvironmental conditions influenced 2-NBDG uptake at both the population and single-cell levels. Glucose uptake of cells were quantified by measuring 2-NBDG relative fluorescence after subjecting nontumorigenic MCF10A and tumorigenic CA1d cell lines to media conditions varying in their growth permissiveness. Conditions used included optimal full growth media (S/S), suboptimal serum-deprived media (EGF), and depleted serum- and EGF-deprived media (0/0), for 24 h prior to labeling (see “Materials and Methods” for detailed descriptions of medium used).

As shown in Fig. 7a, if assessed at the population-level, nontumorigenic the MCF10A cell line exhibited a marked ~3-fold increase in 2-NBDG uptake in optimal conditions (S/S) as compared with suboptimal (EGF) or depleted conditions (0/0). In contrast, the tumorigenic CA1d cell line showed no significant change in uptake under different tested media conditions. These results, confirmed by classic enzymatic-based bulk glucose consumption assays (data not shown), indicated that glucose shuttling may be sensitive to physiological regulation in nontumorigenic MCF10A, but less so in malignant CA1d. Furthermore, double-staining experiments revealed that only ~65% of MCF10A cells consumed 2-NBDG under deprived conditions (0/0), compared with ~70% and 85% in growth permissive conditions (EGF and S/S, respectively) (Fig. 7b). In contrast, the percentage of CA1d cells that were labeled was consistent (~80–90%) across tested media conditions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report showing that while the uptake of 2-NBDG by indolent cells (MCF10A) occurs in a manner specifically dependent upon microenvironmental conditions, 2-NBDG uptake by malignant cells (CA1d) is independent of microenvironmental cues in vitro.

Fig. 7.

Inter-population cell variability is modulated by growth conditions. MCF10A and CA1d cells were cultured for 24 h in optimal (S/S), suboptimal (EGF) or deprived media (0/0), and were subsequently double-labeled with Hoescht and 2-NBDG for measurements of total cell count and glucose uptake, respectively. a The average glucose uptake was determined as fluorescence intensity (a.f.u.), which showed that under suboptimal and deprived growth conditions, MCF10A consumed less 2-NBDG than CA1d under the same conditions. *P<0.05, significant differences. b The percentage of single cells that absorbed 2-NBDG was also calculated. CA1d consistently exhibited a higher percentage of cells that consumed 2-NBDG than MCF10A; however, no significant changes were obtained. c Statistical analysis of single-cell measurements of 2-NBDG uptake revealed the presence of two subpopulations, of low and high glucose uptake, in both cell lines in full culture conditions (S/S). Interestingly, the presence of these two subpopulations persisted in CA1d regardless of growth conditions; however, they disappeared in MCF10A when grown under suboptimal (EGF) or deprived conditions (0/0).

Under optimal growth conditions (S/S), statistical analysis of single-cell distribution further revealed two distinct subpopulations of both MCF10A and CA1d cell lines, at least in terms of 2-NBDG uptake (Fig. 7c). More specifically, fluorescence intensity analysis showed one subpopulation that consumed minimal amounts of 2-NBDG, while a second subpopulation consumed higher levels. The MCF10A subpopulation that consumed high levels of 2-NBDG was diminished in size in suboptimal conditions (EGF), and absent in depleted conditions (0/0). Interestingly, the opposite trend was observed for CA1d cells. That is, two distinctive subpopulations were apparent regardless of the media condition employed. Of note, the subpopulation of highly glycolytic cells was even more pronounced under depleted conditions (0/0). Median 2-NBDG intensity and corresponding 95% CIs for each cell line in each microenvironmental condition are shown in the Electronic supplementary material, Online Resource 3.

These results clearly suggest that intra-population heterogeneity of glucose uptake is modulated by exposure to variation of growth conditions in vitro, and further suggest that glucose uptake by the tumorigenic CA1d cell line occurs in a manner independent of fluctuations in conditions that mimic the tumor microenvironment.

Discussion

The aims of this study were twofold. Firstly, we developed a high-throughput population-based fluorometric assay to allow a rapid, direct, and large-scale assessment of glucose uptake in normal and tumor cells in vitro, which is readily applicable in most common biological laboratory settings. Secondly, we developed a HCAM single-cell-based assay to directly analyze the distribution of glucose uptake rates of single cells within cell populations. In both assays, the cellular accumulation of 2-NBDG, a deoxyglucose fluorescent analog, was exploited as an approximation of glucose uptake rates.

The development of different classes of deoxyglucose analogs has enabled researchers in recent years to directly measure glucose uptake rates of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo, as compared to the classical indirect inferring of population average consumption rates from time-course data [6, 38, 45, 46]. 2-NBDG, however, represents several major advantages over its FDG radioactive analog, including being safe for regular laboratory usage, no requirement for cellular destruction, and allowance of direct visual assessment of glucose uptake in live cells. It is important to point out however that unlike d-glucose, the key rate-limiting steps of glucose analog uptake, such as 2-NBDG and FDG, have not been determined in most cell types, commanding further detailed mechanistic studies in the future. Sequential pharmacological and genetic targeting for GLUTs and hexokinase, and subsequent monitoring of the uptake kinetics of these glucose analogs in the particular cell lines under investigation would be necessary to answer this pivotal question. These approaches can be complemented with other molecular biology approaches, such as over expression of specific GLUTs or hexokinases in the same cell lines and similarly monitoring the changes in uptake kinetics.

Here, we described two independent, but complementary, approaches for making high-throughput measurements of glucose uptake using deoxyglucose fluorescence analog 2-NBDG. Both methods were purposefully designed to make use of multi-well microplates that are commonly used in many biological laboratories. Using a multi-well microplate format allows for rapid and simplified labeling methodology, in comparison with previously published methods using custom-designed microfluidic chambers [19, 38].

The population-based assay we developed was used to measure glucose uptake rates using 2-NBDG in both “normal” and tumor cell lines utilizing a simple multi-well fluorometric microplate reader format. In contrast to previously published methods that use custom-designed microfluidic chambers or flow cytometry assays to measure 2-NBDG uptake [19, 22, 38], our population-based fluorometric microplate assay provides several advantages, i.e., high-throughput, highly quantitative, and readily applicable in common biological laboratory settings. Furthermore, our method is also more practical and less laborious than previously published single-cell assays, such as flow cytometry [23], and especially suits the need for measuring glucose uptake in adherent cells, which are more representative of solid tumors.

Our results from this method show that 2-NBDG uptake is both density- and dose-dependent (Figs. 1 and 2, respectively). Interestingly, these data revealed that CA1d, a breast cancer cell line, exhibits a rate of glucose analog uptake higher than its parental normal mammary epithelia cell line, MCF10A (Figs. 1 and 2), which is consistent with the Warburg effect [3]. Furthermore, this difference in glucose uptake in CA1d and MCF10A cell line has previously been reported by others using an indirect glucose consumption enzymatic assay [47], which was also confirmed in our own lab with the same procedure (data not shown). To test the reliability of our population-based assay, we also measured 2-NBDG uptake in other tumor cell lines, including MCF7 breast cancer and HepG2 hepatocarcinoma (Fig. 2b). The results from these two cell lines were also consistent with previously published results [23, 38].

We further tested whether 2-NBDG is incorporated by GLUTs in MCF10A and CA1d, using competitive d-glucose inhibition assays and pharmacological inhibition of GLUTs with Phloretin (Fig. 3). Indeed, these results indicated that the bulk of 2-NBDG is incorporated in both of these cell lines via GLUTs. On the other hand, it has been recently shown that, as mentioned above, NBDG analogs have a 100-fold higher affinity for GLUTs than d-glucose itself [42]. Therefore, real glucose uptake rates are problematic to measure with this analog and novel probes with improved binding kinetics that mimic d-glucose uptake in live cells need to be developed. Nevertheless, staining intensity provides an excellent approximation a cell’s glucose uptake potential and is useful for relative comparisons across individual cells or cell lines, as well as perturbations. Finally, we showed that glucose uptake of both MCF10A and CA1d was inhibited by treatment with increasing doses of two different classes of small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors Lapatinib and Erlotinib (Fig. 4a, b).

Collectively these results provide strong evidence that our population-based fluorometric assay provides a fairly simple, reproducible, and rapid way to measure glucose uptake in various cell lines in vitro. Hence, this assay provides an ideal platform for large-scale screening of adherent and non-adherent cells in a timely fashion. Nonetheless, a limit of this method is that it can only provide average population measurements for glucose uptake, and therefore misses one of the key characteristics of cancer cell populations, cell level heterogeneity with respect to phenotypic traits dependent on both genetic and non-genetic variability.

Therefore, to gain insight into the underlying distribution spectrum of glucose uptake at the single-cell level within a cell line population, we devised a second HCAM-based method for high-throughput single-cell measurements of glucose uptake. In this assay, cells were doubly labeled with Hoechst staining (to identify nuclei and to be used an internal control for total cell count) and 2-NBDG for obtaining both single-cell measurements of glucose uptake and the percentage of cells that uptake 2-NBDG. Coupling the power of HCAM and semi-automated image analysis software (CellProfiler) allows for in depth analyses of the underlying population dynamics of glucose uptake.

Results from HCA Massays of average population measurements of dose–response and glucose competitive inhibition assays (Fig. 6a, d) confirmed the results from the corresponding population-based fluorometric microplate technique (Figs. 2a and 3a) and further revealed intra-population variability of glucose uptake, as shown from the percentage of 2-NBDG labeled cells versus the total cell population (Figs. 6b, c, e, f). Although the underlying reason(s) behind metabolic heterogeneity is yet to be elucidated, it is tempting to speculate that the variety in physiological states of cells (i.e., proliferation, senescence, quiescence, cell death) or distinct stages of similar physiological states may contribute to this heterogeneity. Alternatively, the cell-to-cell variability may be due to real basal physiological states that the individual cells have achieved. Further studies are needed to clarify this issue, and we expect our assays to be critical to these. Furthermore, the ability of the malignant CA1d to efficiently import the glucose analog 2-NBDG regardless of cell culture conditions raises interesting questions pertaining to the ability of tumorigenic cells to more efficiently utilize available carbon sources, and how this may promote tumor development. Interestingly, a small subpopulation of MCF10A and CA1d cells were able to incorporate 2-NBDG even at low concentrations of the probe. Microscopic examination of MCF10A and CA1d clearly support these observations, in which at least three subgroups of cells exhibited a range of cellular and subcellular uptake distinct phenotypic traits (Fig. 5a).

Taken together, these results strongly support the notion that metabolic heterogeneity observed in tumors in vivo can be explained, at least in part, by intra-population variability intrinsic to cancer cells. Since it is widely accepted that glucose uptake is a dynamic process in non-mammalian and mammalian cells, we also examined if cell culture conditions that mimic the tumor microenvironment had any effect on glucose uptake distribution within cell populations of MCF10A and CA1d cell lines. These results clearly showed that glucose uptake is affected in MCF10A by culturing under different growth conditions (Fig. 7). In contrast, CA1d cells were less affected by changed conditions. Statistical analysis revealed that the CA1d cell line exhibits a bimodal distribution of single-cell glucose uptake in all microenvironmental conditions tested, suggesting potential subpopulations of cells, at least in terms of glucose uptake. In contrast, MCF10A exhibited a bimodal distribution only under optimal conditions (S/S). These results provide a potential in vitro explanation of metabolic heterogeneity observed during in vivo tumor PET scanning [12, 15, 48]. This notion has long been suggested by other groups and has recently been observed in vitro and in vivo in other types of tumors [4, 7, 49].

Conclusion

Developing novel tools that unravel metabolic behavior (i.e., glucose uptake), particularly at the single-cell level in tumor cell populations in culture, will provide an opportunity to tease apart underlying population dynamics and cellular mechanisms. Population-based techniques, such as the fluorometric plate reader assay presented herein, are useful for screening and validation purposes because they are high-throughput and fairly easy to perform and analyze. However, application of single-cell-based assays, such as the HCAM approach we take in this study, provides a higher resolution of cellular data. Further, single-cell assays allow for simultaneous monitoring of other quantitative cellular traits [50], such as proliferation or motility, given appropriate use of markers and image analyses. In summary, combining both approaches can be useful for dissecting the full range of metabolic behavior of tumor cells, which could aid in designing custom therapeutics that selectively target only the most aggressive tumor phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the following funding source for support of this work: NCI U54-CA113007 awarded to VQ. We would also like to thank Dr. David Degraff for his help with the revising the scientific content of this manuscript and for his insightful comments and critiques.

Abbreviations

- 0/0

DMEM without serum and supplements

- 2-DG

2-Deoxglucose

- 2-NBDG

2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxyglucose

- a.f.u.

Arbitrary fluorescence units

- CI

Confidence interval

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- FDG

2-Deoxy2-[F-18] fluoro-d-glucose

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- GLUTs

Glucose transporters

- HCAM

High-content automated microscopy

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- S/S

DMEM with serum and supplements

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11307-010-0399-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of Interest Statement. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123(3191):309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tennant DA, et al. Metabolic transformation in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(8):1269–1280. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124(3215):269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deberardinis RJ, et al. Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu PP, Sabatini DM. Cancer cell metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell. 2008;134(5):703–707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czernin J, Phelps ME. Positron emission tomography scanning: current and future applications. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:89–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones RG, Thompson CB. Tumor suppressors and cell metabolism: a recipe for cancer growth. Genes Dev. 2009;23(5):537–548. doi: 10.1101/gad.1756509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christofk HR, et al. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 2008;452(7184):230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auerbach R, Auerbach W. Regional differences in the growth of normal and neoplastic cells. Science. 1982;215(4529):127–134. doi: 10.1126/science.7053564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franzius C, et al. Evaluation of chemotherapy response in primary bone tumors with F-18 FDG positron emission tomography compared with histologically assessed tumor necrosis. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25(11):874–881. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenny L, et al. Imaging early changes in proliferation at 1 week post chemotherapy: a pilot study in breast cancer patients with 3′- deoxy-3′-[18F]fluorothymidine positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34(9):1339–1347. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mankoff DA, et al. Tumor-specific positron emission tomography imaging in patients: [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose and beyond. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(12):3460–3469. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eary JF, et al. Spatial heterogeneity in sarcoma 18F-FDG uptake as a predictor of patient outcome. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(12):1973–1979. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshioka K, et al. Evaluation of 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1, 3- diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxy-D-glucose, a new fluorescent derivative of glucose, for viability assessment of yeast Candida albicans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;46(4):400–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00166236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshioka K, et al. Intracellular fate of 2-NBDG, a fluorescent probe for glucose uptake activity, in Escherichia coli cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60(11):1899–1901. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshioka K, et al. A novel fluorescent derivative of glucose applicable to the assessment of glucose uptake activity of Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1289(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada K, et al. A real-time method of imaging glucose uptake in single, living mammalian cells. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(3):753–762. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Natarajan A, Srienc F. Dynamics of glucose uptake by single Escherichia coli cells. Metab Eng. 1999;1(4):320–333. doi: 10.1006/mben.1999.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lloyd PG, Hardin CD, Sturek M. Examining glucose transport in single vascular smooth muscle cells with a fluorescent glucose analog. Physiol Res. 1999;48(6):401–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada K, et al. Measurement of glucose uptake and intracellular calcium concentration in single, living pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(29):22278–22283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908048199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou C, Wang Y, Shen Z. 2-NBDG as a fluorescent indicator for direct glucose uptake measurement. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2005;64(3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barros LF, et al. Preferential transport and metabolism of glucose in Bergmann glia over Purkinje cells: a multiphoton study of cerebellar slices. Glia. 2009;57(9):962–970. doi: 10.1002/glia.20820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loaiza A, Porras OH, Barros LF. Glutamate triggers rapid glucose transport stimulation in astrocytes as evidenced by real-time confocal microscopy. J Neurosci. 2003;23(19):7337–7342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07337.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porras OH, Loaiza A, Barros LF. Glutamate mediates acute glucose transport inhibition in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24(43):9669–9673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1882-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demartino NG, McGuire JM. The multicatalytic proteinase: a high-Mr endopeptidase. Biochem J Lett. 1988;255:750–751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaudreault N, et al. Subcellular characterization of glucose uptake in coronary endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 2008;75(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng Z, et al. Near-infrared fluorescent deoxyglucose analogue for tumor optical imaging in cell culture and living mice. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17(3):662–669. doi: 10.1021/bc050345c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roman Y, et al. Confocal microscopy study of the different patterns of 2-NBDG uptake in rabbit enterocytes in the apical and basal zone. Pflugers Arch. 2001;443(2):234–239. doi: 10.1007/s004240100677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimitriadis G, et al. Evaluation of glucose transport and its regulation by insulin in human monocytes using flow cytometry. Cytom A. 2005;64(1):27–33. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheth RA, Josephson L, Mahmood U. Evaluation and clinically relevant applications of a fluorescent imaging analog to fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14(6):064014. doi: 10.1117/1.3259364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones TR, et al. Cell Profiler Analyst: data exploration and analysis software for complex image-based screens. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pauley RJ, et al. The MCF10 family of spontaneously immortalized human breast epithelial cell lines: models of neoplastic progression. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1993;2(Suppl 3):67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang NS, Soule HD, McGrath CM. Expression of murine mammary tumor virus-related antigens in human breast carcinoma (MCF-7) cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;59(5):1357–1367. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouma ME, et al. Further cellular investigation of the human hepatoblastoma-derived cell line HepG2: morphology and immunocytochemical studies of hepatic-secreted proteins. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1989;25(3 Pt 1):267–275. doi: 10.1007/BF02628465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vokes MS, Carpenter AE. Using CellProfiler for automatic identification and measurement of biological objects in images. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1417s82. (Chapter 14):Unit 14.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Neil RG, Wu L, Mullani N. Uptake of a fluorescent deoxyglucose analog (2-NBDG) in tumor cells. Mol Imaging Biol. 2005;7(6):388–392. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-0011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salter DW, Custead-Jones S, Cook JS. Quercetin inhibits hexose transport in a human diploid fibroblast. J Membr Biol. 1978;40(1):67–76. doi: 10.1007/BF01909739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobori M, et al. Phloretin-induced apoptosis in B16 melanoma 4A5 cells by inhibition of glucose transmembrane transport. Cancer Lett. 1997;119(2):207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim MS, et al. Phloretin induces apoptosis in H-RasMCF10A human breast tumor cells through the activation of p53 via JNK and p38 mitogenactivated protein kinase signaling. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1171:479–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barros LF, et al. Kinetic validation of 6-NBDG as a probe for the glucose transporter GLUT1 in astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2009;109(Suppl 1):94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cameron DA, Stein S. Drug Insight: intracellular inhibitors of HER2–clinical development of lapatinib in breast cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5(9):512–520. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louzao MC, et al. “Fluorescent glycogen” formation with sensibility for in vivo and in vitro detection. Glycoconj J. 2008;25(6):503–510. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z, et al. Metabolic imaging of tumors using intrinsic and extrinsic fluorescent markers. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004;20(3):643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nitin N, et al. Molecular imaging of glucose uptake in oral neoplasia following topical application of fluorescently labeled deoxyglucose. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(11):2634–2642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richardson AD, et al. Central carbon metabolism in the progression of mammary carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110(2):297–307. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9732-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franzius C, et al. FDG-PET for detection of osseous metastases from malignant primary bone tumours: comparison with bone scintigraphy. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27(9):1305–1311. doi: 10.1007/s002590000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sonveaux P, et al. Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(12):3930–3942. doi: 10.1172/JCI36843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quaranta V, et al. Trait variability of cancer cells quantified by high-content automated microscopy of single cells. Methods Enzymol. 2009;467:23–57. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)67002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.