Abstract

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and tauopathies, tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, undergoes a conformational change, and becomes aggregated and insoluble. There are three methods commonly used to study the insoluble tau fraction, two that utilize detergents (Sarkosyl and RIPA) and another that does not (insoluble). However, these methods require large amounts of homogenate for a relatively low yield of the insoluble fraction, which can be problematic when dealing with small tissue samples. Furthermore, the most common way of analyzing this material is through densitometry of immunoblots, offering only semiquantitative measurements. We provide a comparison of the three methods commonly used (Sarksoyl, RIPA, and insoluble) through immunoblot and ELISA analyses. Finally, we tested a new method to determine aggregated tau levels, utilizing a monoantibody tau ELISA. The insoluble fractions of four different mouse models (P301 L, htau, wild type, and knockout) as well as human AD and control brains were examined. There were significant correlations between the three insoluble methods for both total tau and pS396/404 tau measured by immunoblot or ELISA analyses. Additionally, the results from the ELISA method correlated significantly with those from immunoblot analyses. Finally, the monoantibody assay on the lysate significantly correlated with the total tau ELISAs performed on the three insoluble preparations. Taken together, these results suggest that all three insoluble preparation methods offer similar results for measuring insoluble tau in either mouse or human brains. In addition the new monoantibody ELISA offers a simple quantitative method to measure the amount of aggregated tau in both human and mouse brains.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, ELISA, immunoblotting, methodology, tau protein, transgenic mice

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disease and the most common form of dementia. Pathologically, AD is characterized by the formation of two protein lesions, intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, composed of hyperphosphorylated tau, and extracellular senile plaques composed of amyloid-β. Amyloid pathology is an important component of AD, however, tau pathology better correlates with neuronal loss and severity of dementia. [1–3]. Additionally, tau mutations have been identified in patients with frontotemporal dementia, which further demonstrates the importance of tau pathology in dementia [4–6].

In AD and other tauopathies, tau becomes hyper-phosphorylated, undergoes a conformational change, and eventually becomes aggregated and insoluble [7]. A similar progression of tau pathology is seen in tau transgenic mouse models, including the human tau (htau) mice and JNPL3 (P301 L) mice. Htau mice have a non-mutated human tau transgene and express all 6 isoforms of the normal human tau protein, without the expression of endogenous mouse tau [8]. P301 L mice overexpress the most frequent tau mutation in FTDP-17, a 0N4R human tau with the P301 L mutation in addition to endogenous mouse tau [9]. There are three different methods currently used to examine the amount of aggregated insoluble tau. Isolations that utilize detergents, either sarkosyl (SARK) [7] or radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA) [10] in the high speed spin, or a third method where no detergent is added (INS) [11]. With these methods the relatively small amount of insoluble tau in human and mice brains can be isolated in the presence of much larger amounts of nonaggregated soluble tau. However, these methods require large amounts of brain homogenate and produce a low yield of the insoluble tau fraction, which can be problematic when dealing with small tissue samples or regional brain dissections. Furthermore, the most common technique of analyses is by immunoblotting, which offers only a semiquanitative measurement of the insoluble tau levels.

In the current study we have compared the three methods of isolating the insoluble tau fraction in four different mouse lines (P301 L, htau, wild type, and knockout), as well as confirmed human AD and healthy control patients. Using both quantitative ELISA and semiquantitative immunoblots, we provide a direct comparison of the three methods by analyzing the total insoluble tau and insoluble pS396/404 tau levels. Additionally, a new quantitative method to measure aggregated tau levels, utilizing a monoantibody tau ELISA (DA9-DA9HRP), has been developed. Overall, data from all three insoluble preparations (insoluble, Sarkosyl, and RIPA) significantly correlate; therefore any one of these preparations can reasonably be used to assess the insoluble fractions in human and mouse brains. Additionally, the total tau and pS396/404 quantitative tau ELISAs significantly correlate with the semiquantitative immunoblot, confirming the usefulness of the tau ELISAs in measuring tau pathology in both human and mouse. Finally, the new monoantibody tau ELISA serves as another useful quantitative technique to analyze the insoluble tau fraction in human brains and tau mouse models. This monoantibody ELISA is a potentially more efficient method to measure aggregated tau, by offering the opportunity to examine the tau levels as pathology progresses and to assess how potential therapeutics might affect aggregated tau in mouse models of tauopathy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue preparations

Human brains

Access to human postmortem brain tissue was approved by the The Albert Einstein College of Medicine Human Research Protection Program. Post-mortem tissue from eight AD (ages 61–77, average 70.5) and two healthy control (HC) (ages 74, 88, average 81) subjects was used. All brains were removed within 18 h of death (mean autopsy delay±1 SD 11.9±5 h). AD cases were selected by clinical and neuropathological criteria (abundance of cortical amyloid-β deposits and neurofibrillary tangles, minimum Braak Stage 6), while HC cases had no history of psychiatric or neurologic disease and no significant findings on neuropathologic examination. A portion of the mid temporal gyrus was dissected out and weighed. Frozen brain tissue was homogenized in 10 volumes of homogenizing buffer, a solution of Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4 containing, 1 mM NaVO3, 2 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, and 1 complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail per 10 ml (Roche). Homogenates were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use.

Mouse brains

All experimental procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine IACUC.

The following mouse models were used:

Wild type (WT) mice (C57BL6J, normal endogenous mouse tau);

Tau knockout (KO) mice that have a targeted disruption of exon 1 of tau [13];

Htau mice that were generated in our laboratory [8] by crossing 8c mice that express a tau transgene from a human PAC [14] with tau knockout mice that have a targeted disruption of exon 1 of tau [13]. Htau mice express all six isoforms of the normal human tau protein without the expression of endogenous mouse tau;

JNPL3 mice, a tau cDNA model that express 0N4R human tau with a P301 L mutation on a mouse tau background. They were generated by Lewis et al. [9] and purchased from Taconic.

Mouse brains were dissected; forebrain was used for WT, tau KO, and htau mice, and whole brain minus the cerebellum was used for the P301 L mice. Homogenates were prepared from 4-month-old tau KO mice (n = 2), 13-month-oldWTmice (n = 2), htau mice averaging 15.25 months old (12–19 months) (n = 4), and 6 month old P301 L mice (n = 5). Homogenates were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use.

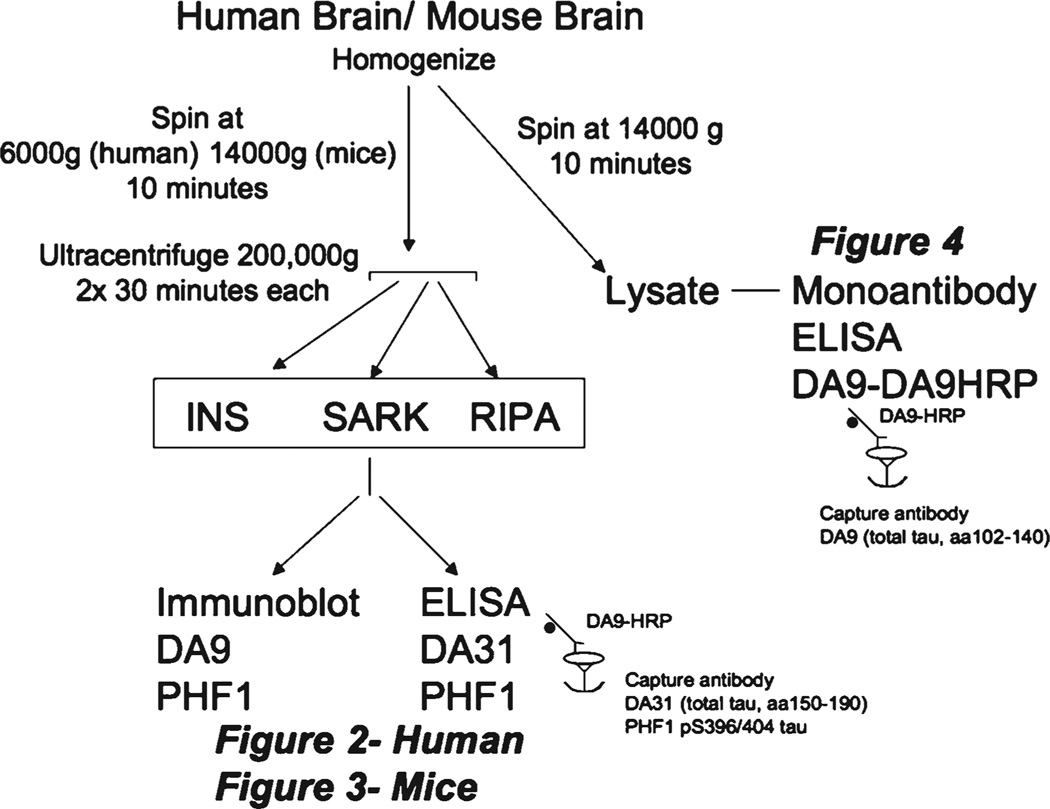

Experimental design (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. Human and mouse brains were dissected and a portion was homogenized. A low speed spin (6,000 g for 10 min) was performed on homogenates. Supernatant was collected and then used for the two high-speed spins for the insoluble preparations, with or without detergent as noted. The insoluble preparations were analyzed with total tau and pS396/404, through ELISAs and immunoblots. Additionally, lysate was prepared and analyzed using our newly developed monoantibody ELISA to detect aggregated tau.

Three insoluble preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) and one lysate preparation were made from the homogenate of each human and mouse brain sample. The three insoluble preparations were analyzed for tau levels with immunoblots probed with antibody DA9 (aa 102–140) and PHF1 (pS396/404), as well as a Low-tau sandwich ELISA for total tau and pS396/404 tau. The lysate was directly assayed for aggregated tau using the newly developed monoantibody ELISA.

Sample preparation

For the three different insoluble preparations for human brains, 500 µl of brain homogenate was centrifuged at 6,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. For mouse brains, 500 µl of brain homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant was collected from this low speed spin. For the SARK and RIPA preparations, the supernatant was incubated for 10 min on an orbital shaker with 1% sarksoyl or 1% RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, 150m M NaCl, 1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS, pH 8.0) respectively. For the INS preparation, no detergent was added to the supernatant. All three preparations were ultracentrifuged for 30 min at 200,000 g at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended in 450 µl of homogenizing buffer and underwent a second spin at 200,000 g for 30 min at room temperature. The supernatant was carefully removed and the pellet was resuspsended in 200 µl of 1×Laemmli sample buffer, to obtain the final INS, SARK, or RIPA preparation. For the lysate preparation, brain homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C.

Tau immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described [15]. Briefly, the final INS, SARK, and RIPA samples were boiled for 5 min, equal volumes were loaded, then separated using 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Once transferred, membranes were probed with PHF1, specific for dual pS396/404 tau [16] and DA9 recognizing total tau, aa 102–140 [12]. Bands were then detected with either enhanced chemiluminsecence (ECL Millipore) or 4-chloronaphthol with 1% hydrogen peroxide (4CN) depending on their intensity. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ.

ELISAs

DA31 and PHF1 tau ELISA

Low-tau sandwich ELISAs were performed as previously [12]. Briefly, 96 well plates were coated with 6 µg/ml of DA31 (total tau, aa 150–190) or PHF1 (pS396/404 tau) in coating buffer, a solution containing 15 mM KH2PO4, 25 mM KH2PO4, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 M EDTA, and 7.5 mM NaN3, pH 7.2, for at least 48 h at 4°C. Plates were washed, then blocked with StartingBlock (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. The INS, SARK, and RIPA preparations were diluted in 20% Superblock in 1×TBS (Thermo Scientific) and samples were added to the plate. The total tau detection antibody, DA9-HRP (total tau, aa 102–140) diluted 1 : 50 in 20% Superblock in 1×TBS was added to the samples and tapped to combine. Plates were then incubated overnight at 4°C. The following day, plates were washed and 1-Step ULTRA TMB-ELISA (Thermo Scientific)was added for 30 min at room temperature. Finally, 2 M sulfuric acid was added to stop the reaction, and plates were read with an Infinite m200 plate reader (Tecan) at 450 nm.

Tau monoantibody ELISA

96 well plates were coated with 50 µl of DA9 (total tau, aa 102–140) at a concentration of 6 µg/ml in coating buffer for at least 48 h at 4°C. Plates were washed 3×in wash buffer then blocked with Starting- lock (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. Lysate was prepared as previously described. The lysate preparations were diluted 1 : 250 for human samples and 1 : 10 for mice samples in 20% Superblock in 1×TBS (Thermo Scientific). 50 µl/well of samples in duplicate, and PHF-tau ([17]: see [12]) as a standard, were incubated overnight at 4°C. The following day plates were washed 5×and then 50 µl/well of the total tau detection antibody DA9-HRP diluted 1 : 50 in 20% Superblock in 1×TBS was added to the plate and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The plates were washed 5× and 50 µl/well of 1-Step ULTRA TMB-ELISA (Thermo Scientific) was added and allowed to incubate at room temperature. After 30 min, 2 M sulfuric acid was added to stop the reaction, and plates were read with an Infinite m200 plate reader (Tecan) at 450 nm. Since monomeric rtau (rPeptide) cannot be detected on the DA9 monoantibody plate, a sample of PHF-tau was used as standard. The tau concentration of the PHF-tau sample was determined by direct comparison on the standard DA31 total tau ELISA.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Graph-Pad Prism Prism (Prism 5.Od, GraphPad Software In, La Jolla, California, USA). For all correlations, a linear regression analysis was performed and the R squared and p values are reported. Correlations were also analyzed with non-parametric (Spearman) methods, and the results were essentially unchanged. A one way ANOVA with Tukeys post-hoc test was used for comparison of the tau levels of the three insoluble preparations (INS versus SARK, INS versus RIPA, SARK versus RIPA) as well as when comparing the aggregated tau levels of the four mouse models with the monoantibody ELISA. An unpaired t-test was used when comparing the aggregated tau levels between HC and AD brains

RESULTS

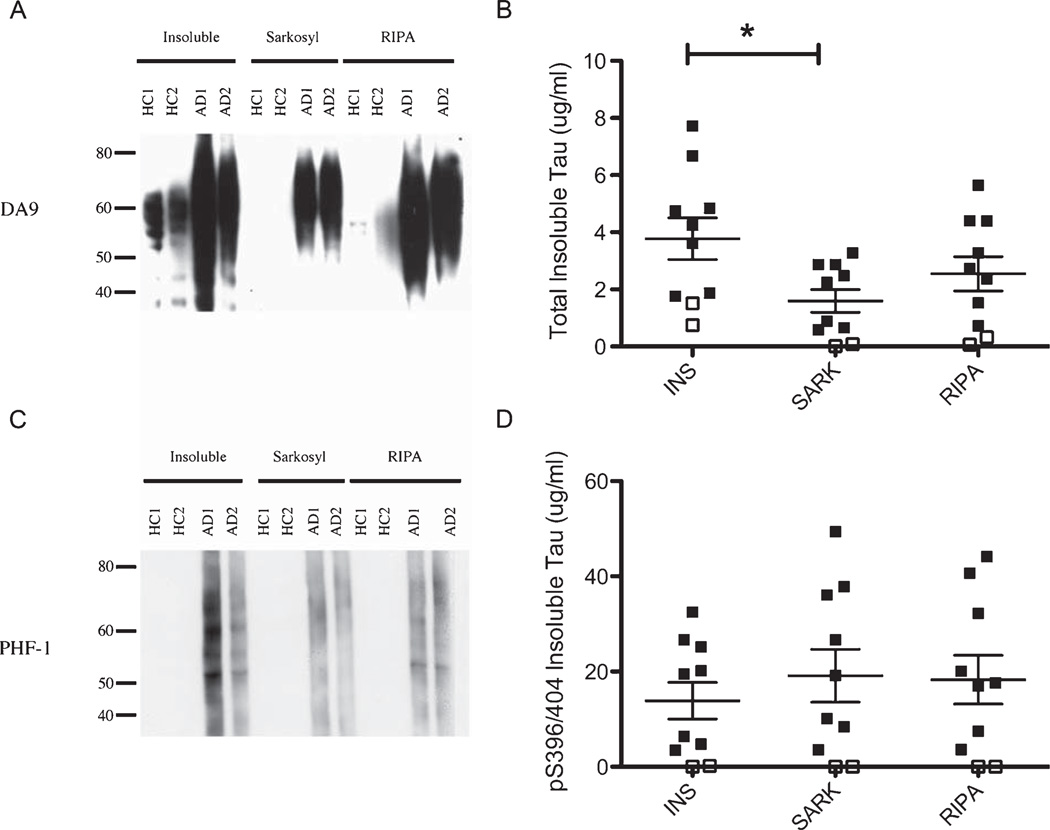

Increased levels of total tau and pS396/404 tau in the insoluble fraction of AD brains compared to HC brains

In humans, it is well established that there is more insoluble tau and insoluble pS396/404 tau in brains of patients with AD compared to HC, and our results further validate this finding. Regardless of which insoluble preparation was assayed (INS, SARK, and RIPA) by immunoblot (Figs. 2A, C) or ELISA (Figs. 2B, D), there is more total tau and pS396/404 tau in the insoluble fractions from AD brains compared to HC brains. The production of an insoluble tau fraction without detergents (INS) does lead to the detection of significant normal tau, recognized by the total tau antibody, in the fraction from healthy control brains, and to a lesser extent this is true of the RIPA fractions. The SARK preparation method appears to significantly reduce the amount of normal tau that is found in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Total tau immunoblot and ELISA and pS396/404 tau immunoblot and ELISA in human brains. A) DA9 (total tau) immunoblot of the three insoluble tau preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) on AD and HC brains. Note the presence of tau in the INS and RIPA fractions prepared from HC brain samples. These bands are not reactive with PHF1 (see Fig. 1C) B) DA31 ELISA measuring total insoluble tau levels of the three insoluble tau preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) on AD and HC brains (□= HC, ■= AD). A one way ANOVA with Tukeys post-hoc test was used for comparison of the total tau levels between the INS and SARK preparations, *p < 0.05. C) PHF 1 (pS396/404 tau) immunoblot of the three insoluble tau preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) on AD and HC brains. D) PHF 1 ELISA measuring pS396/404 insoluble tau levels of the three insoluble tau preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) on AD and HC brains (□= HC, ■= AD).

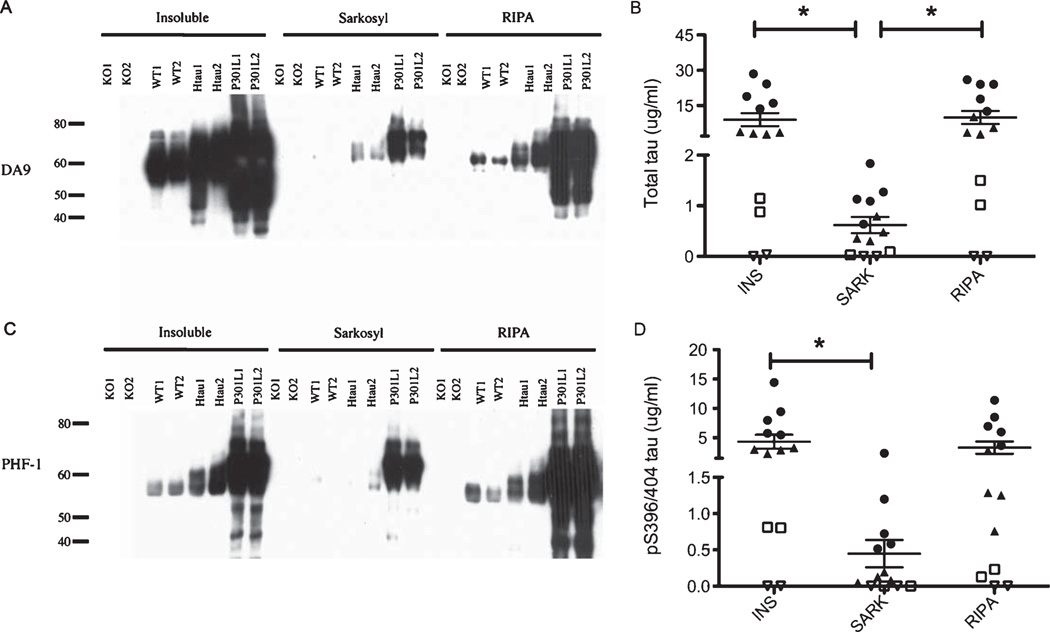

Increased levels of total tau and pS396/404 tau in the insoluble fraction of tau transgenic mice compared to wild type and tau knockout mice

For the mouse preparations, as expected there is no detectable tau in the tau KO mice in any preparation. Additionally, regardless of which insoluble preparation assayed (INS, SARK, RIPA) by both immunoblot (Figs. 3A, C) and ELISA (Figs. 3B, D), the trend for the amount of total tau and pS396/404 tau is consistently KO<WT < htau < P301 L. However, the SARK preparation has significantly less total tau compared to the INS and RIPA preparations (Fig. 3B) and significantly less pS396/404 tau compared to the INS preparation (Fig. 3D). The SARK preparation method appears to significantly reduce the amount of normal tau that is found in the insoluble fraction, as judged by the amount of insoluble tau in the preparations from wild type mice (3A and 3 C).

Fig. 3.

Total tau immunoblot and ELISA and pS396/404 tau immunoblot and ELISA in mouse brains. A)DA9 (total tau) immunoblot of the three insoluble tau preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) on the four mouse models (KO, WT, htau, P301 L). B) DA31 ELISA measuring total insoluble tau levels of the three insoluble tau preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) on the four mouse models (∇=KO, □=WT, ▲= htau, • = P301 L). A one way ANOVA with Tukeys post-hoc test was used for comparison of the total tau levels between the INS and SARK preparations, and between the RIPA and SARK preparations, *p < 0.05. C) PHF 1 (pS396/404 tau) immunoblot of the three insoluble tau preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) on AD and HC brains. D) PHF 1 ELISA measuring pS396/404 insoluble tau levels of the three insoluble tau preparations (INS, SARK, RIPA) on the four mouse models (∇=KO, □=WT, ▲= htau, • = P301 L). A one way ANOVA with Tukeys post-hoc test was used for comparison of the pS396/404 tau levels between the INS and SARK preparations, *p < 0.05.

The three insoluble preparations correlate with each other in both human and mice brain

All correlations are significant in both human and mouse brain samples when comparing the three insoluble preparations (INS versus SARK, INS versus RIPA, and SARK versus RIPA) with both methods of analyses, immunoblot or ELISA, with each of two relevant tau epitopes examined, total tau and pS396/404. While the SARK preparation appears to most effectively remove normal tau, yields of insoluble tau from the other two methods correlate strongly with the SARK method results (Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlations between data from different methods of isolation and assay of insoluble tau

| Human |

Mouse |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Preparation | R2 Value | p value | R2 Value | p value |

| DA9 immunoblot | INS versus SARK | 0.750 | 0.0012 | 0.805 | <0.0001 |

| INS versus RIPA | 0.823 | 0.0003 | 0.887 | <0.0001 | |

| SARK versus RIPA | 0.798 | 0.0005 | 0.932 | <0.0001 | |

| PHF1 immunoblot | INS versus SARK | 0.778 | 0.0007 | 0.987 | <0.0001 |

| INS versus RIPA | 0.772 | 0.0008 | 0.975 | <0.0001 | |

| SARK versus RIPA | 0.697 | 0.0027 | 0.979 | <0.0001 | |

| DA31 ELISA | INS versus SARK | 0.762 | 0.0010 | 0.721 | 0.0002 |

| INS versus RIPA | 0.864 | 0.0001 | 0.753 | 0.0001 | |

| SARK versus RIPA | 0.842 | 0.0002 | 0.928 | <0.0001 | |

| PHF1 ELISA | INS versus SARK | 0.844 | 0.0002 | 0.929 | <0.0001 |

| INS versus RIPA | 0.868 | <0.0001 | 0.940 | <0.0001 | |

| SARK versus RIPA | 0.779 | 0.0007 | 0.884 | <0.0001 | |

| DA9 immunoblot versus DA31 ELISA |

INS | 0.921 | <0.0001 | 0.959 | <0.0001 |

| SARK | 0.937 | <0.0001 | 0.792 | <0.0001 | |

| RIPA | 0.878 | <0.0001 | 0.892 | <0.0001 | |

| PHF1 immunoblot versus PHF1 ELISA |

INS | 0.543 | 0.0151 | 0.901 | <0.0001 |

| SARK | 0.827 | 0.0003 | 0.770 | <0.0001 | |

| RIPA | 0.841 | 0.0003 | 0.905 | <0.0001 | |

The semiquantitative immunoblots densitometry correlates with the quantitative analyses of the low tau sandwich ELISAs

Although the immunoblots offer only a semiquantitative method to measure tau concentrations by using densitometry, the values in arbitrary units derived from this analysis significantly correlate with the quantitative results in µg/ml of tau derived from the ELISAs. All the correlations are significant in either human and mouse samples, when comparing the DA9 immunoblot to DA31 ELISA and PHF1 immunoblot to PHF1 ELISA, with each of the three different insoluble methods (Table 1).

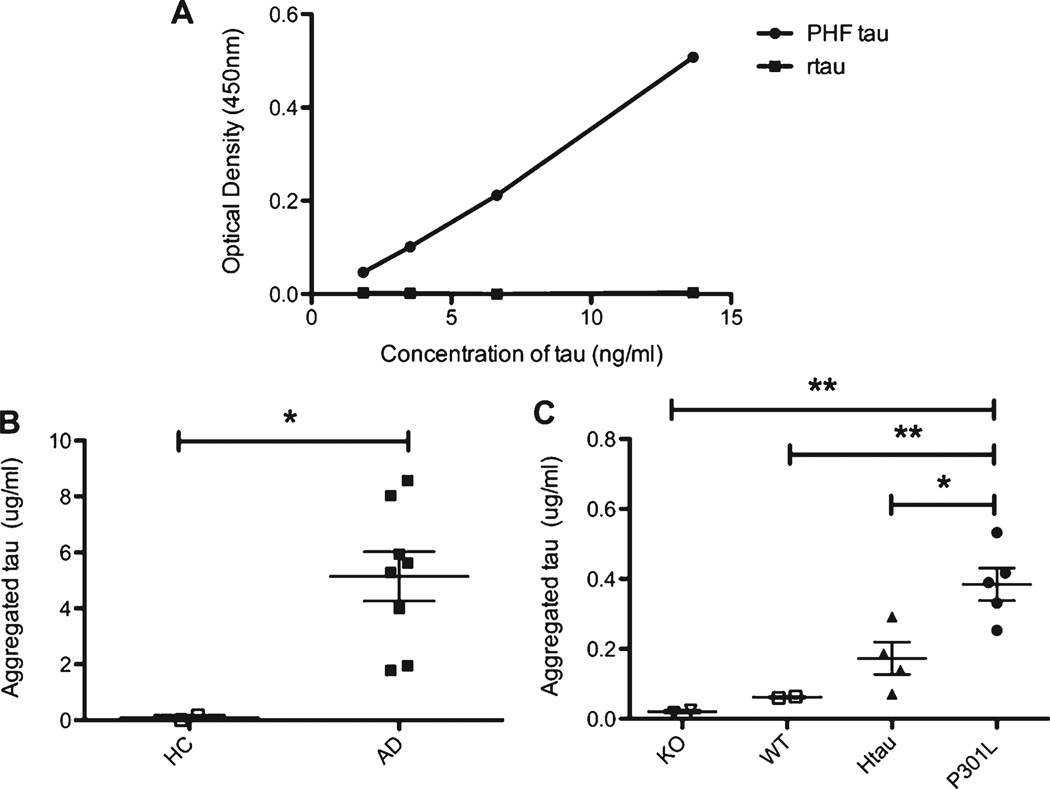

A monoantibody ELISA offers a simple quantitative method to measure the amount of aggregated tau in both human and mouse brains

One major limitation of isolating insoluble tau with the INS, SARK, and RIPA preparations is the large amount of homogenate required to obtain an adequate sample for tau analyses. Developing a reliable tau monoantibody ELISA, which uses significantly less sample, would greatly improve the opportunity to examine aggregated tau. This monoantibody ELISA utilizes the DA9 (aa 102–140) total tau antibody as the capture antibody and an HRP linked DA9 antibody as the detection antibody. PHF-tau isolated from AD brains, which has multiple tau sites present for binding gives a robust signal. However, no signal is detected in recombinant tau despite the presence of the DA9 epitope, since this form of tau is monomeric (Fig. 4A). This validates the usefulness of this assay in recognizing the aggregated but not monomeric form of tau. There is a significant increase in aggregated tau in AD brains compared to healthy controls (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the same trend is followed in mice that was observed with the DA31 assay that KO<WT < htau < P30 L in the amount of aggregated tau (Fig. 4C). The amount of aggregated tau in the lysate correlates significantly with both the total tau immunoblot and ELISA of the three insoluble preparations in human and mice brains (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Monoantibody ELISA (DA9-DA9-HRP) titration curve and total levels of aggregated tau in human and mouse brain lysate. A) Titration curve of recombinant tau and PHF-tau isolated from AD brains on the monoantibody ELISA. There is a robust signal with PHF-tau; however, no signal is present with the monomeric recombinant tau. B) Total levels of aggregated tau in human brain lysate assessed by the monoantibody ELISA (□= HC, ■= AD). An unpaired t-test was used for comparison of aggregated tau levels between HC and AD brains, *p < 0.05. C) Total levels of aggregated tau in mice brain lysate assessed by the monoantibody ELISA (∇=KO, □=WT, ▲= htau, • = P301 L). A one way ANOVA with Tukeys post-hoc test was used for comparison of the aggregated tau levels between the P301 L mice with the KO, WT, and htau mice, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Table 2.

Monoantibody ELISA aggregated tau results correlate with ELISA assay data on isolated insoluble tau.

| Human |

Mouse |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Preparation | R2 Value | p value | R2 Value | p value |

| DA9 Immunoblot (insoluble) versus | INS | 0.9482 | <0.0001 | 0.8754 | <0.0001 |

| DA9 monoantibody ELISA (Lysate) | SARK | 0.7264 | 0.0017 | 0.8318 | <0.0001 |

| RIPA | 0.8625 | 0.0001 | 0.8954 | <0.0001 | |

| DA31 ELISA (insoluble) versus | INS | 0.9309 | <0.0001 | 0.7435 | 0.0001 |

| DA9 monoantibody ELISA (Lysate) | SARK | 0.7149 | 0.0021 | 0.9447 | <0.0001 |

| RIPA | 0.9017 | <0.0001 | 0.8960 | <0.0001 | |

DISCUSSION

In AD and other tauopathies, tau becomes hyper-phosphorylated and undergoes a conformational change and eventually becomes aggregated and insoluble [7]. There are several protocols currently used to isolate and quantitate this insoluble tau fraction in both mouse and human brains [7, 10, 11]. These methods allow the isolation of small amounts of aggregated tau in the presence of large amounts of soluble non-aggregated tau in the brain. It is possible to calculate from the data in [12] that the insoluble tau makes up less than 5% of the total tau concentration, even in the P301 L mouse. In the current study we compared the three most popular insoluble preparations (INS, RIPA, SARK) in tau transgenic mouse models, WT, and tau KO mice as well as in AD and HC brains. The insoluble fractions were assayed with both immunoblots and a low tau sandwich ELISA in order to measure total and pS396/404 tau. We observed that there was a significant correlation between each isolation method in mouse and human samples, and when comparing total tau and pS396/404 amounts. However, there were some differences in the total amount of tau between the preparations in both human and mouse brains, which can be seen in the ELISA and immunoblot (Figs. 1, 2). The DA9 immunoblot of the insoluble preparations of human brains was purposefully overexposed to show tau present in the HCs of the INS preparation but absent in the SARK preparation, which goes along with the findings in the DA31 ELISAs. In the mice, based on DA9 immunoblots and DA31 ELISA, tau is present in the INS and RIPA preparations of WT mice but absent in the SARK preparation of WT mice. Since there is no aggregated insoluble tau in healthy control patients or wild type mice, one possible explanation is contamination of tau bound to other insoluble proteins in the pellet. It appears that adding sarkosyl to the preparation gets rid of this potential tau contamination and therefore is the most specific preparation for isolating aggregated tau. Therefore, if specificity is desirable, SARK is most efficient. However, if a pathological tau antibody, for example PHF-1 in human samples, is being used on these insoluble preparations, any of the three preparations may be used, since all three correlate to one another. Chai and colleagues [11] also reported similar results when they compared the INS and SARK preparations of four P301 L (JNPL3) mouse brain samples with their AT8 (pS202/T205 tau) ELISA. They observed a highly significant correlation between the two, with the INS preparation giving a higher signal than the SARK preparation [11]. However, our study is the first to compare all three insoluble tau preparations in both human brains (HC and AD) as well as in multiple tau transgenic mouse lines, (htau, P301 L), WT mice, and tau KO mice.

Due to the limited availability of epitope specific tau ELISAs, the most popular way of analyzing insoluble tau in both AD brains and tau transgenic mice models is with immunoblots. Tau immunoblots are difficult to quantify because DA9 and PHF1 react with numerous bands in the insoluble tau fraction, and it becomes difficult to determine which bands to include or exclude for densitometry. It is also difficult to quantitate from immunoblots of samples containing very different levels of reactivity, and it is important to be consistent and run each preparation (INS, SARK, RIPA) for human or mouse on the same gel and develop with the same technique in order to perform densitometry. Further, the densitometry analysis yields arbitrary units and can be difficult to relate to absolute tau concentrations.

Recently our laboratory developed a low tau ELISA that offers a good alternative to the semiquantitative immunoblotting for analysis of the tau insoluble fraction [12]. It allows quantitation of total tau and pS396/404 of the insoluble fraction of human and mouse brains. Additionally, in this study we have demonstrated a significant correlation between the immunoblot densitometry units and the quantitative tau levels in µg/ml derived from the ELISAs.

A new method to measure aggregated tau levels with a monoantibody tau ELISA (DA9-DA9HRP) has been developed with several benefits. The insoluble preparations, INS, SARK, and RIPA, require large amounts of homogenate for a low yield of the insoluble fraction, which can be problematic when dealing with small tissue samples. A relatively small amount of lysate can be used for this ELISA, containing about 1 µg of protein in human brain tissue samples and 60 µg protein in mouse brain samples, allowing for fine tissue dissection and a region specific analysis of aggregated tau. Additionally, the insoluble preparations are difficult to prepare, they involve numerous high-speed spins, and resupsension of a pellet that is often difficult to visualize. Our new monoantibody ELISA offers a potentially more efficient method to measure the amount of aggregated tau in both human and mice brains which will be useful in understanding the role that insoluble tau has in the progression of AD and other tauopathies. Additionally, this is a valuable method to assess potential therapeutics and understand how the treatments can affect the insoluble tau fraction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by the National Institutes of Health (AG022102).

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://www.j-alz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=1487)

REFERENCES

- 1.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42:631–639. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bancher C, Braak H, Fischer P, Jellinger KA. Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer lesions and intellectual status in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurosci Lett. 1993;162:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90590-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez-Isla T, Hollister R, West H, Mui S, Growdon JH, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Hyman BT. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:17–24. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen RC, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Che LK, Norton J, Morris JC, Reed LA, Trojanowski J, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Neystat M, Fahn S, Dark F, Tannenberg T, Dodd PR, Hayward N, Kwok JB, Schofield PR, Andreadis A, Snowden J, Craufurd D, Neary D, Owen F, Oostra BA, Hardy J, Goate A, van Swieten J, Mann D, Lynch T, Heutink P. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poorkaj P, Kas A, D’Souza I, Zhou Y, Pham Q, Stone M, Olson MV, Schellenberg GD. A genomic sequence analysis of the mouse and human microtubule-associated protein tau. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:700–712. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-2044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg SG, Davies P. A preparation of Alzheimer paired helical filaments that displays distinct tau proteins by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5827–5831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andorfer C, Kress Y, Espinoza M, de Silva R, Tucker KL, Barde YA, Duff K, Davies P. Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau in mice expressing normal human tau isoforms. J Neurochem. 2003;86:582–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J, Melrose H, Nacharaju P, Van Slegtenhorst M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Paul Murphy M, Baker M, Yu X, Duff K, Hardy J, Corral A, Lin WL, Yen SH, Dickson DW, Davies P, Hutton M. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat Genet. 2000;25:402–405. doi: 10.1038/78078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang B, Higuchi M, Yoshiyama Y, Ishihara T, Forman MS, Martinez D, Joyce S, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Retarded axonal transport of R406W mutant tau in transgenic mice with a neurodegenerative tauopathy. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4657–4667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0797-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chai X, Wu S, Murray TK, Kinley R, Cella CV, Sims H, Buckner N, Hanmer J, Davies P, O’Neill MJ, Hutton ML, Citron M. Passive immunization with anti-Tau antibodies in two transgenic models: Reduction of Tau pathology and delay of disease progression. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34457–34467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.229633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acker CM, Forest SK, Zinkowski R, Davies P, d’Abramo C. Sensitive quantitative assays for tau and phosphotau in transgenic mouse brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker KL, Meyer M, Barde YA. Neurotrophins are required for nerve growth during development. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:29–37. doi: 10.1038/82868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duff K, Knight H, Refolo LM, Sanders S, Yu X, Picciano M, Malester B, Hutton M, Adamson J, Goedert M, Burki K, Davies P. Characterization of pathology in transgenic mice over-expressing human genomic and cDNA tau transgenes. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:87–98. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andorfer CA, Davies P. PKA phosphorylations on tau: Developmental studies in the mouse. Dev Neurosci. 2000;22:303–309. doi: 10.1159/000017454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otvos L, Jr, Feiner L, Lang E, Szendrei GI, Goedert M, Lee VM. Monoclonal antibody PHF-1 recognizes tau protein phosphorylated at serine residues 396 and 404. J Neurosci Res. 1994;39:669–673. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jicha GA, O’Donnell A, Weaver C, Angeletti R, Davies P. Hierarchical phosphorylation of recombinant tau by the paired-helical filament-associated protein kinase is dependent on cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurochem. 1999;72:214–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]