Abstract

AIM: To compare the clinical outcome of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-positive ulcerative colitis (UC) patients with and without antiviral therapy.

METHODS: This was a retrospective case-controlled study. The database of UC patients in our institution was scanned for documented presence of CMV on colonic biopsies. Demographics, clinical data, endoscopy findings and pathology reports were extracted from the patients’ charts and electronic records. When available, the data from colonoscopies preceding and following the diagnosis of colonic CMV infection were also extracted. The primary outcomes of the study were colectomy/death during hospitalization and the secondary outcomes were colectomy/death through the course of the follow-up.

RESULTS: Thirteen patients were included in the study, 7 (53.5%) of them were treated with gancyclovir and 6 (46.5%) were not. Patients treated with antivirals presented with a more severe disease and 57% of them were treated with cyclosporine or infliximab before initiation of gancyclovir, while none of the patients without antivirals required rescue therapy. One patient died and another patient underwent urgent colectomy during hospitalization, both of them from the gancyclovir-treatment group. For the entire follow-up time (13 ± 13 mo), a total of 3 colectomies and one death occurred, all among the antiviral-treated patients (for colectomy: 3/7 vs 0/6 patients, P = 0.19; for combined adverse outcome: 4/7 vs 0/6 patients, P = 0.07). In 9/13 patients, immunohistochemistry for CMV was performed on biopsies obtained during a subsequent colonoscopy and was positive in one patient only.

CONCLUSION: Gancyclovir-treated patients had a more severe disease and outcome, probably unrelated to antiviral therapy. Immunohistochemistry-CMV-positive patients with mild disease may recover without antiviral therapy.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Cytomegalovirus, Gancyclovir, Cyclosporine, Immunohistochemistry

INTRODUCTION

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is very common in the healthy adult population, with reported rates of CMV-IgG positivity of up to 100%, depending on the age and geographical location[1]. In immuno-compromised patients (post-solid organ transplantation, chemotherapy-treated, human immunodeficiency virus, recipients of immunosuppressive drugs, for instance), CMV infection or reactivation may lead to a systemic disease or end-organ involvement manifesting as severe pneumonitis, hepatitis or colitis[2].

In patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis, CMV has been reported to be present in the colonic tissue of 21%-34% of patients and of 33%-36% of steroid refractory cases, respectively[3].

The clinical significance of detecting CMV in UC patients remains debatable[4,5]. It has been suggested that CMV infection may be a marker of a more severe disease that is more likely to be refractory to corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy[6,7]. Conversely, some authors suggest that CMV may only be an "innocent bystander", reflecting a remote infection of the involved mucosa and lacking a significant impact on patient outcome[8,9].

Several laboratory techniques are employed for the detection of CMV colitis, including hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining for evidence of a cytopathic damage in epithelial cells, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). As most of the patients who are tested for CMV in the colonic mucosa are afflicted with a severe and treatment-resistant disease, the vast majority of them are treated with antiviral medications (gancyclovir, foscarnet) upon the diagnosis of CMV. However, the clinical benefit of this strategy is still not clear due to a paucity of reports of the outcome of CMV-positive patients who were not treated with antivirals.

In this manuscript, we describe the clinical course and outcome of 6 patients with ulcerative colitis who tested positive for CMV in the colonic mucosa but did not receive antiviral therapy, in comparison to 7 patients who were treated with anti-viral medications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

This was a retrospective case-cohort study. The study cohort included all patients who were in Sheba Medical Center between 2007 and 2011 for an exacerbation of ulcerative colitis and who tested positive for CMV by IHC in colonic biopsies. Patients with Crohn’s disease or indeterminate colitis were excluded from the study.

Data collection

Clinical, endoscopic and laboratory data were retrieved from the patients' charts and electronic records. When available, endoscopic and pathological data from previous (before the index episode) and subsequent colonoscopies were also extracted.

Histological examination

All samples were examined by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist for evidence of a cytopathic damage (inclusion bodies) on HE stains.

CMV immunostaining: IHC staining for CMV was performed on all samples. Briefly, formalin fixed tissues from patients were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 μm. A positive control was added on the right side of the slides. The CMV immunostaining was calibrated on a Benchmark XT staining module (Ventana Medical Systems). The slides were warmed to 60 °C for 1 h and after that processed to a fully automated protocol. Briefly, after sections were dewaxed and rehydrated, a Protease 2 (Ventana Medical Systems) pretreatment during 8 min for antigen retrieval was selected. The CMV antibody (Clones CCH2 + DDG9, M0854, Dako) was diluted 1:25 and incubated for 24 min at 37 °C. Detection was performed with iView DAB Detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems). Counterstaining was performed for 4 min in hematoxylin (Ventana Medical Systems). After the automated staining was completed, the slides were dehydrated in 70% ethanol, 95% ethanol and 100% ethanol for 1 min in each ethanol concentration. Before cover-slipping, the sections were cleared in xylene for 1 min and mounted with Entellan.

Statistical analysis

The demographic and clinical parameters of CMV-positive patients treated with gancyclovir were compared to those of patients who did not receive antiviral therapy.

Continuous variables were analyzed by student t-test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables. P < 0.05 was considered significant. The analysis was performed with Medcalc statistical software version 11 (Mariakerke, Belgium).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Thirteen patients were included in the study, 7 of whom received antivirals. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Patients in the antiviral-treated group had a longer duration of disease (14.2 ± 9.3 years vs 3.5 ± 1.8 years, P = 0.008). Ten patients required hospitalization for severe exacerbation of ulcerative colitis, whereas three were treated as outpatients.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the included patients (mean ± SD)

| Patient characteristics | Treated (n = 7) | Untreated (n = 6) | P vaule |

| Age (yr) | 50.0 ± 14.6 | 45.0 ± 13.6 | 0.540 |

| Gender (male/female) | 4/3 | 3/3 | 0.400 |

| Extent of disease | |||

| Pancolitis | 6 | 5 | 0.540 |

| Left- sided | 1 | 1 | 0.540 |

| Age on diagnosis of UC, yr | 35.7 ± 13.3 | 41.5 ± 13.3 | 0.530 |

| Duration of disease, yr | 14.2 ± 9.3 | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 0.008 |

| Hospitalized patients | 6 | 4 | 0.560 |

| Prehospitalization treatment | |||

| SC | 4 | 2 | 0.560 |

| Thiopurines | 3 | 2 | 1.000 |

| Infliximab | 11 | 0 | 1.000 |

| 5-asa | 5 | 4 | 1.000 |

| SC + thiopurines | 2 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Treatment during hospitalization | |||

| SC | 6 | 3 | 0.400 |

| Infliximab | 1 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Cyclosporine | 3 | 0 | 0.200 |

| Timing of colonoscopy (d) | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 2.7 ± 3.4 | 0.600 |

| Positive cytopathic changes on HE | 2 | 0 | 0.460 |

| Hospitalization outcome | |||

| Death | 1 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Colectomy | 1 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Outcome by the of the follow-up | |||

| Colectomy | 3 | 0 | 0.190 |

| Death | 1 | 0 | 1.000 |

1Combined with systemic corticosteroids and thiopurine. Treated: Patients who received antiviral therapy; Untreated: Patients who did not receive antiviral therapy; Timing of colonoscopy: Number of days from hospital admission; SC: Systemic corticosteroids; HE: Hematoxylin eosin; IHC: Immunohistochemistry; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

Nine out of the 10 (90%) hospitalized patients were treated with systemic corticosteroids on admission. Four patients received second-line treatment (3 patients-cyclosporine, 1 patient-infliximab).

Diagnosis of CMV

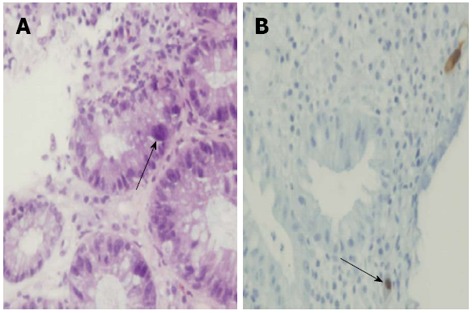

Immunochemistry for CMV was positive in all patients (Figure 1A). Cytopathic changes consistent with CMV infection in the form of inclusion bodies (Figure 1B) were detectable in only 2/13 (15%) of the patients (both patients received antivirals).

Figure 1.

Cytomegalovirus demonstrated on a colonic biopsy in a patient with ulcerative colitis (arrows). A: Hematoxylin eosin staining; B: Immunohistochemistry.

Additional tests for detection of CMV infection were performed in only a few of the patients. CMV IgM was assessed in 2 patients, one of them was seropositive. Five patients were tested for CMV DNA in the peripheral blood by quantitative PCR, of whom only one was found to be positive (1900 copies/mL). This patient had a severe and resistant disease and underwent total colectomy during the hospitalization after failure of intravenous corticosteroid, cyclosporine and antiviral therapy.

Antiviral treatment

Seven patients received antivirals. One patient received oral valgancyclovir as an outpatient for 1 mo. Six patients were treated with intravenous gancyclovir for 10.3 ± 7.8 d. One of the patients died and another underwent colectomy. Three out of 4 remaining patients were discharged with oral valgancyclovir. Cyclosporine was discontinued in 2/3 patients upon detection of CMV in the colonic mucosa.

Patients' outcomes

In the antiviral-treated group, one patient died from uncontrolled gastroduodenal bleeding and one patient underwent colectomy during the initial hospitalization for severe treatment-resistant colitis. Two additional patients (both received gancyclovir) underwent colectomy during the course of follow-up (13 ± 13 mo) (3/7 vs 0/6 patients, P = 0.19). Thus, 4/7 patients in the anti-viral treated group experienced an adverse outcome (colectomy/death) compared to 0/6 adverse outcomes in those who did not receive antivirals (P = 0.07).

Evolution of CMV status

In 2 patients, negative CMV status (both IHC and HE) was documented on a colonoscopy preceding the index examination. CMV status was assessed by a subsequent colonoscopy in 9 patients (after 4.7 ± 5.5 mo). Immunostaining for CMV was positive in only one of these patients.

DISCUSSION

In this case series, we have compared the outcome of CMV-positive UC patients who were treated with antivirals with the outcome of patients who received conventional anti-inflammatory therapy. In general, the latter group presented with a milder disease, as reflected by the fact that only half of them (3/6) were hospitalized and none required salvage cyclosporine or infliximab treatment. The long-term outcome of these patients during extended follow-up was also favorable.

Although evidence of CMV infection in the inflamed colonic mucosa of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients is quite common, reportedly higher in steroid-resistant patients[10,11], the actual clinical significance of this finding remains unclear. Cytomegalovirus is trophic for inflamed and replicating tissue and commonly affects patients on systemic immunosuppression[3,4]. Evidence of viral shedding and replication is often found in IBD patients, almost exclusively in the inflamed mucosa[1]. However, it remains unsettled whether the presence of virus in the tissue is a trigger or a byproduct of the inflammation. Moreover, studies of the outcome of CMV colitis in IBD rarely include a detailed description of the non-treated cohort, thereby hampering our knowledge on the true impact of this viral infection. In addition, the definitions of CMV infection vary significantly and depend on the diagnostic technique employed.

Earlier reports have included steroid-resistant patients with evidence of CMV-induced cytopathic damage on HE staining (“inclusion bodies”)[10,12,13]. These patients had a severe disease and high rates of colectomy (up to 67%)[12]. A detection of inclusion bodies on HE staining is clinically relevant[3] and implies an ongoing destruction of colonocytes by the virus. Unfortunately, this technique has low sensitivity (10%-87%)[1], primarily due to a sampling error, and potentially misses a significant number of patients. Immunohistochemistry with a monoclonal antibody targeting early CMV antigen may improve the diagnostic sensitivity to the range of 78%-93%[1,6]. Current European Crohn's and Colitis Organization guidelines recommend the combination of HE staining and IHC for detection of CMV infection in patients with UC flare-up[14]. In addition to these techniques, CMV DNA can be detected in various substrates, such as serum or full blood, by PCR. Although very sensitive, this method is subject to a significant heterogeneity stemming from employment of non-standardized commercial kits and lack of a standardized cutoff value for active infection. Moreover, there is a poor correlation between viral replication in the blood and the presence or pathogenic viral activity in the gut in IBD patients[1]. The same is true for detection of viral antigens in the blood (such as pp65) which is also poorly associated with viral-mediated gut injury.

In addition to its detection in the blood, CMV DNA can be also demonstrated in the colonic tissue by PCR. This highly sensitive technique often leads to the detection of the virus in the absence of histological evidence of tissue damage, thereby possibly representing a remote infection or a low-key viral replication of unclear significance[1].

Recently, several reports utilizing quantitative real-time PCR for detection of CMV infection in patients with UC have been published. Yoshino et al[15] tested the colonic biopsies of thirty patients with severe immunosuppressive-resistant ulcerative colitis. CMV DNA (defined as > 10 copies/μg by quantitative real-time PCR) was demonstrated in 56.7% of the patients and was limited to the inflamed mucosa. Seventy percent of these patients were treated with gancyclovir and 83.3% of them achieved remission. In contrast, 93.3% of the CMV-DNA negative patients achieved remission with immunosuppressive therapy. In the study by Roblin et al[16], CMV DNA load above 250 copies/mg in tissue was predictive of resistance to three successive anti-inflammatory regimens.

The impact of detectable CMV on the clinical course of a UC flare-up is still debated. Some authors suggest that CMV reactivation is associated with a worse clinical outcome and with a treatment-refractory disease[6,7,11,17,18], but other studies have not supported this association[8,15,19]. The impact of antiviral therapy on the outcome of CMV-positive patients with UC is also debatable[4,5]. Based on several series, the cumulative rate of short-term response of CMV-positive patients to gancyclovir therapy is 72%[1,5,11,15]. The outcome of patients who did not receive gancyclovir has not been extensively reported. Kim et al[20] described the outcome of 31 CMV-positive patients with ulcerative colitis. Only steroid-resistant patients were treated with gancyclovir and 11/14 responded to the treatment. All the steroid responsive CMV-positive patients had a favorable outcome regardless of anti-viral treatment. In the study by Roblin et al[16], 37.5% (6/16) of patients with CMV DNA load > 250 copies/mg still responded to successive lines of immunosuppressive therapy. This could indicate that CMV presence in the tissue may not in itself preclude a possible response to intensified immunosuppression without antivirals.

In this context, our study provides several important observations. Primarily, the outcome of patients who were not treated with antivirals was favorable (no deaths or colectomies). However, the patients in the antiviral-treated group seem to have presented with a more severe disease, as reflected by their greater need for rescue cyclosporine/infliximab therapy and by their greater need of hospitalization. Antiviral therapy was usually withheld if clinical improvement was noted by the time CMV results were received from the laboratory. Therefore, there was probably a bias towards administration of antiviral therapy to the patients with a more severe disease who failed to improve on standard therapy during their hospitalization. It appears that the decision to start antiviral therapy was guided by the severity of the disease rather than merely the histological findings. The underlying severity of the disease is probably responsible for the inferior clinical outcome of the patients who received antiviral therapy, indicating once more that the sheer presence of CMV in tissue probably does not in itself dictate the clinical outcome.

Interestingly, 9/13 patients were tested for the presence of CMV by IHC on a subsequent colonoscopy and only one patient (who was not treated with antivirals) was positive. This is consistent with the findings reported by Matsuoka et al[9], who demonstrated frequent cycles of reactivation (defined by positive CMV-antigenemia or plasma PCR) and spontaneous clearance of CMV in immunosuppressed patients[21-23]. Therefore, in at least a subgroup of patients with exacerbation of UC, the presence of CMV may be an epiphenomenon of the inflammatory process rather than a causative agent.

Our study has several important limitations, primarily stemming from its retrospective design and small sample size. Long-term follow-up was available for only a minority of the patients. The treatment and control groups were significantly different regarding severity of the disease. Indeed, the decision to withhold antiviral therapy was generally adopted for patients who improved clinically by the time the histological results were available, thereby underlining once more the dissimilarity between the two groups. Finally, we did not routinely perform assays for CMV IgM, CMV DNA or pp65 in the serum. None of these methods reliably reflect the presence of the virus in the colonic tissue, although they are useful in diagnosis of disseminated CMV infection.

Despite these limitations, our findings imply that patients with clear histological evidence of CMV presence in the colonic tissue may not universally require antiviral therapy and may respond to conventional anti-inflammatory therapy. The presence of CMV does not necessarily bear a significant impact on the course of the flare-up in all patients. In particular, less severe patients may probably be treated safely with conventional anti-inflammatory therapy alone, as long as they are responsive. Clearly, larger prospective placebo-controlled trials are called for in order to resolve the etiological role of CMV in severe UC and to elucidate the benefit of anti-viral treatment for these cases. Such studies, preferably utilizing a quantitative rather than qualitative CMV-detection technique, may help to establish a threshold differentiating active infection from low key reactivation and may therefore prove useful in guiding the management of suspected CMV involvement in UC patients.

COMMENTS

Background

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is often present in the mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. However, the clinical impact of this finding on the course of the disease and the impact of antiviral therapy on the clinical outcome are still subject to significant debate.

Research frontiers

In the retrospective cohort, the patients who were treated with antivirals were hospitalized with a more severe disease and had more adverse outcomes compared to the patients who did not receive antivirals. This higher rate of adverse outcome probably stems from the severity of the disease rather than the treatment itself.

Innovations and breakthroughs

These findings suggest that CMV-positive ulcerative colitis (UC) patients with relatively mild disease may not require specific antiviral treatment as long as they respond to the conventional anti-inflammatory treatment.

Applications

This is a small retrospective study. Large prospective controlled studies are required in order to identify the optimal treatment strategy in CMV-positive UC patients.

Terminology

CMV belongs to the family of herpesviridae. It is a very frequent pathogen in healthy subjects as well as immunocompromised patients. CMV can be frequently demonstrated in the mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis by a conventional staining with hematoxylin and eosin or by immunostaining (immunohistochemistry) with specific antibodies that are able to identify the traces of the viral genome in the tissue.

Peer review

The results are well presented and discussed in a very balanced and comprehensive way. Despite the small number of patients included in this study, the work deserves publication as it may have important implications for the treatment of ulcerative colitis patients.

Footnotes

Supported by Lecturer Fees from Abbott and Shering-Plough

P- Reviewer Nevels M S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Lu YJ

References

- 1.Lawlor G, Moss AC. Cytomegalovirus in inflammatory bowel disease: pathogen or innocent bystander? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1620–1627. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manuel O, Perrottet N, Pascual M. Valganciclovir to prevent or treat cytomegalovirus disease in organ transplantation. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9:955–965. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kandiel A, Lashner B. Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2857–2865. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hommes DW, Sterringa G, van Deventer SJ, Tytgat GN, Weel J. The pathogenicity of cytomegalovirus in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and evidence-based recommendations for future research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:245–250. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200405000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domènech E, Vega R, Ojanguren I, Hernández A, Garcia-Planella E, Bernal I, Rosinach M, Boix J, Cabré E, Gassull MA. Cytomegalovirus infection in ulcerative colitis: a prospective, comparative study on prevalence and diagnostic strategy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1373–1379. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kambham N, Vij R, Cartwright CA, Longacre T. Cytomegalovirus infection in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:365–373. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minami M, Ohta M, Ohkura T, Ando T, Ohmiya N, Niwa Y, Goto H. Cytomegalovirus infection in severe ulcerative colitis patients undergoing continuous intravenous cyclosporine treatment in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:754–760. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i5.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lévêque N, Brixi-Benmansour H, Reig T, Renois F, Talmud D, Brodard V, Coste JF, De Champs C, Andréoletti L, Diebold MD. Low frequency of cytomegalovirus infection during exacerbations of inflammatory bowel diseases. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1694–1700. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuoka K, Iwao Y, Mori T, Sakuraba A, Yajima T, Hisamatsu T, Okamoto S, Morohoshi Y, Izumiya M, Ichikawa H, et al. Cytomegalovirus is frequently reactivated and disappears without antiviral agents in ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:331–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berk T, Gordon SJ, Choi HY, Cooper HS. Cytomegalovirus infection of the colon: a possible role in exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cottone M, Pietrosi G, Martorana G, Casà A, Pecoraro G, Oliva L, Orlando A, Rosselli M, Rizzo A, Pagliaro L. Prevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in severe refractory ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:773–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Begos DG, Rappaport R, Jain D. Cytomegalovirus infection masquerading as an ulcerative colitis flare-up: case report and review of the literature. Yale J Biol Med. 1996;69:323–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loftus EV, Alexander GL, Carpenter HA. Cytomegalovirus as an exacerbating factor in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:306–309. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199412000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahier JF, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, Conlon C, De Munter P, D’Haens G, Domènech E, Eliakim R, Eser A, Frater J, et al. European evidence-based Consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:47–91. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshino T, Nakase H, Ueno S, Uza N, Inoue S, Mikami S, Matsuura M, Ohmori K, Sakurai T, Nagayama S, et al. Usefulness of quantitative real-time PCR assay for early detection of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with ulcerative colitis refractory to immunosuppressive therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1516–1521. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roblin X, Pillet S, Oussalah A, Berthelot P, Del Tedesco E, Phelip JM, Chambonnière ML, Garraud O, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Pozzetto B. Cytomegalovirus load in inflamed intestinal tissue is predictive of resistance to immunosuppressive therapy in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2001–2008. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kishore J, Ghoshal U, Ghoshal UC, Krishnani N, Kumar S, Singh M, Ayyagari A. Infection with cytomegalovirus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence, clinical significance and outcome. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:1155–1160. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadakis KA, Tung JK, Binder SW, Kam LY, Abreu MT, Targan SR, Vasiliauskas EA. Outcome of cytomegalovirus infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2137–2142. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimitroulia E, Spanakis N, Konstantinidou AE, Legakis NJ, Tsakris A. Frequent detection of cytomegalovirus in the intestine of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:879–884. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000231576.11678.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YS, Kim YH, Kim JS, Cheon JH, Ye BD, Jung SA, Park YS, Choi CH, Jang BI, Han DS, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in patients with new onset ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1098–1101. doi: 10.5754/hge10217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavagna A, Bergallo M, Daperno M, Sostegni R, Costa C, Leto R, Crocellà L, Molinaro G, Rocca R, Cavallo R, et al. Infliximab and the risk of latent viruses reactivation in active Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:896–902. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheinberg P, Fischer SH, Li L, Nunez O, Wu CO, Sloand EM, Cohen JI, Young NS, John Barrett A. Distinct EBV and CMV reactivation patterns following antibody-based immunosuppressive regimens in patients with severe aplastic anemia. Blood. 2007;109:3219–3224. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torre-Cisneros J, Del Castillo M, Castón JJ, Castro MC, Pérez V, Collantes E. Infliximab does not activate replication of lymphotropic herpesviruses in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:1132–1135. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]