Abstract

Background

Understanding individual differences in susceptibility to antidepressant therapy side-effects is essential to optimize the treatment of depression.

Method

We performed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to search for genetic variation affecting the susceptibility to side-effects. The analysis sample consisted of 1439 depression patients, successfully genotyped for 421K single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Outcomes included four indicators of side-effects: general side-effect burden, sexual side-effects, dizziness and vision/hearing-related side-effects. Our criterion for genome-wide significance was a prespecified threshold ensuring that, on average, only 10% of the significant findings are false discoveries.

Results

Thirty-four SNPs satisfied this criterion. The top finding indicated that 10 SNPs in SACM1L mediated the effects of bupropion on sexual side-effects (p=4.98×10−7, q=0.023). Suggestive findings were also found for SNPs in MAGI2, DTWD1, WDFY4 and CHL1.

Conclusions

Although our findings require replication and functional validation, this study demonstrates the potential of GWAS to discover genes and pathways that could mediate adverse effects of antidepressant medication.

Keywords: Depression, genome-wide association study, pharmacogenomics, side-effects, single nucleotide polymorphisms, STAR*D

Introduction

Antidepressants are the cornerstone of acute and long-term treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). At present, there are four primary classes of antidepressants available on the US market. They are distinguished by their mechanisms of action (MOAs): selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Each class has multiple representatives available from different manufacturers. In addition, there are other (‘atypical’) antidepressants with alternative MOAs that do not belong in these primary classes, such as bupropion (a dopamine–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) and mirtazapine (an α2 adrenergic receptor antagonist). These atypical antidepressants are often prescribed as an alternative or adjunct to the primary classes because of their superior sexual side-effect profiles (Serretti & Chiesa, 2009; Frost et al. 2010).

Clinical trials suggest that only 50–60% of patients with uncomplicated MDD respond to any single antidepressant (Papakostas & Fava, 2009), and general clinical experience suggests even lower response rates (Kirchheiner et al. 2004; Souery et al. 2007). Compounding the difficulty of identifying successful treatment, antidepressant use is frequently associated with adverse drug reactions, with the inability to tolerate side-effects being the most common reason for discontinuing antidepressant therapy (Maddox et al. 1994; Bull et al. 2002a, b; Mitchell, 2006). Clinicians currently have no way to predict individual efficacy and side-effect profiles, and trial-and-error switching often leaves MDD patients in psychological distress for weeks or months. Clearly, improved methods of patient–antidepressant matching to minimize side-effects would greatly improve depression treatment.

Studies have consistently indicated that antidepressant response is substantially heritable (Pare & Mack, 1971; Oreilly et al. 1994; Franchini et al. 1998; Malhotra et al. 2004), suggesting that pharmacogenomic approaches represent a particularly promising avenue toward individualizing antidepressant treatment. Preliminary pharmacogenetic research has, for example, suggested an important role for genes related to serotonin function in antidepressant side-effects (Kato & Serretti, 2010; Zobel & Maier, 2010; Porcelli et al. 2011). The serotonergic system is involved in the regulation of many physiological functions that are disturbed in depression, including neuroendocrine mechanisms regulating reproductive events such as ovulation, spermatogenesis and sexual behavior (Segraves, 1989; Pollack et al. 1992; Ayala, 2009; Kato & Serretti, 2010; Zobel & Maier, 2010). However, to date, robust consistent evidence implicating any specific candidate gene or polymorphism to antidepressant side-effect response has been rare. More generally, candidate gene approaches are inherently restricted by our current, limited knowledge of the biological mechanisms underlying depression and antidepressant MOAs. Methods that systematically screen variants across the whole genome for association with antidepressant side-effects are therefore crucial to discovering relevant variants in novel genes. Furthermore, such approaches have begun to yield tangible results, with the number of new replicated marker–disease associations increasing dramatically since the introduction of genome-wide association studies (GWAS; Altshuler et al. 2008), and some initial applications in the context of drug response (Byun et al. 2008; Link et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2008a; Lavedan et al. 2009; Aberg et al. 2010a, b; Adkins et al. 2011; McClay et al. 2011a, b).

In this study, we used a GWAS approach to search for genetic variation affecting the susceptibility for antidepressant-induced side-effects. Our study sample consisted of the 1439 MDD patients who did not respond to citalopram-only treatment from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study (Rush et al. 2004). The drug-specific analyses were performed on the four primary side-effect dimensions indicated by factor analyses of a battery of 35 side-effect indicators (Rush et al. 2004).

Method

STAR*D

Subjects came from the STAR*D study, which has been described in detail elsewhere (Rush et al. 2004). In brief, STAR*D is a multistage trial of different treatment options for patients with non-psychotic MDD. STAR*D enrolled a total 4041 out-patients with MDD (Wisniewski et al. 2006). In level 1, patients were given citalopram. Those patients who did not have an efficacious response, or could not tolerate side-effects, to citalopram only were then randomized to other treatment options in other levels, 2a or 2–4. Other treatment options included, but were not limited to, sertraline, bupropion, buspirone, cognitive therapy, various combinations of these treatments, and using one of these treatments in combination with citalopram. This study focuses exclusively on the 1439 patients who did not benefit from citalopram only and those treatment options with at least 100 patients, which were bupropion, buspirone, sertraline, venlafaxine, citalopram + bupropion and citalopram + buspirone. The results of a GWAS of the side-effects for the citalopram treatment options will be presented in a separate publication (Adkins et al., unpublished observations).

Measures

Side-effect presence and tolerance were measured by the Patient Rated Inventory of Side-Effects (PRISE; Rush et al. 2004). For each of the eight biological systems assessed (gastrointestinal, heart, skin, nervous system, vision/hearing, genital/urinary, sleep and sexual functioning), patients were asked two types of questions, one relating to specific side-effects (e.g. dry mouth, heart palpitations) and one relating to the overall tolerability of side-effects for a given biological system. For the specific side-effects, patients were asked to indicate whether the side-effect was present (0 = no side-effect, 1 = side-effect present). There were four items for the gastrointestinal system, three for the heart system, four for skin, four for the nervous system, two for vision/hearing, four for the genital/urinary system, two for sleep and four for sexual functioning. In addition, an overall score of side-effect tolerability was given for each of the eight biological systems as a trichotomous item with the follow categories: 0 = no side-effects, 1 = tolerable side-effects, 2 = distressing side-effects (Wisniewski et al. 2006).

Side-effect phenotype specification

Specifying side-effect phenotypes for the GWAS proceeded in two steps. The first was to condense the 35 side-effect indicators of the PRISE using factor analysis, thereby improving measurement by identifying the latent phenotypic constructs underlying the battery of side-effect indicators (Bollen, 1989; Loehlin, 2004). The second was to estimate the treatment effects for each drug based on the factor scores obtained (van den Oord et al. 2009).

Factor analysis

Using Mplus 6.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010), exploratory factor analyses were conducted to examine the factor structure of the 35 side-effect indicators of the PRISE scale. Of the several potential factors emerging from the exploratory analyses, four were retained based on overall fit to the data, interpretability, and having a Cronbach’s α >0.70, which indicates good reliability of the factor (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). The four factors were: (1) a general side-effect burden factor in which all of the symptom measures served as factor indicators, (2) a sexual factor, (3) a dizziness factor, and (4) a factor relating to vision/hearing. Once the optimal factor structure was determined, factor scores for each of the four factors were calculated using the standard regression scoring approach. The factor loadings and Cronbach’s α for each factor are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Factor loadings for side-effect factors

| BS | Item | Factor

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE | Dizziness | Sex | Vision/hearing | ||

| GI | Diarrhea | 0.24 | |||

| Constipation | 0.27 | ||||

| Dry mouth | 0.38 | ||||

| Nausea/vomiting | 0.31 | ||||

| GI tolerability | |||||

| Heart | Palpitations | 0.29 | |||

| Dizziness on standing | 0.58 | 0.83 | |||

| Chest pain | 0.35 | ||||

| Heart tolerability | 0.74 | ||||

| Skin | Rash | 0.23 | |||

| Increased perspiration | 0.3 | ||||

| Itching | 0.38 | ||||

| Dry skin | 0.35 | ||||

| Skin tolerability | |||||

| CNS | Headache | 0.37 | |||

| Tremors | 0.32 | ||||

| Poor coordination | 0.43 | ||||

| Dizziness | 0.56 | 0.68 | |||

| CNS tolerability | |||||

| Vision/hearing | Blurred vision | 0.44 | 0.65 | ||

| Ringing in ears | 0.35 | 0.63 | |||

| Eyes/ear tolerability | 0.92 | ||||

| Genital/urinary | Difficulty urinating | 0.25 | |||

| Painful urination | 0.21 | ||||

| Menstrual irregularity | 0.08 | ||||

| Frequent urination | 0.33 | ||||

| Genital/urinary tolerability | |||||

| Sleep | Difficulty sleeping | 0.3 | |||

| Sleeping too much | 0.07 | ||||

| Sleep tolerability | |||||

| Sex | Loss of sexual desire | 0.26 | 0.65 | ||

| Trouble achieving orgasm | 0.18 | 0.56 | |||

| Trouble with erections | 0.22 | 0.44 | |||

| Sex tolerability | 0.88 | ||||

| α | 0.74 | 0.8 | 0.71 | 0.75 | |

BS, Biological system; GSE, general side-effect; GI, gastrointestinal ; CNS, central nervous system.

The factor analysis results presented in Table 1 were based on all observations for an individual irrespective of treatment or time spent on a treatment. Given that side-effects vary by antidepressant and number of days taking a specific drug (Demyttenaere et al. 2005), additional factor analyses were performed that divided the STAR*D sample based on which treatment a patient was given and the number of days on a given treatment. This was done to confirm that the factor solution was robust across drugs and treatment duration, and not artifactual due to heterogeneity across time or drug. Another confounding issue in treatment with antidepressants is the presence of anxiety because individuals with anxiety disorders often present with symptoms similar to depression (e.g. irritability, sleeping problems, etc.), anxiety and depression often co-occur, and most importantly, perception of the presence and severity of side-effects could potentially be influenced by anxiety independently of actual side-effects (Barbee, 1998; Regier et al. 1998). Thus, the factor analyses discussed above were repeated controlling for anxiety status. Similar factors emerged with similar patterns of loadings when the sample was broken down by treatment, days on drug and when controlling for anxiety. Because all factor structures were similar to what was found in the overall factor analysis, the sensitivity results are not presented here (available upon request).

Estimating treatment effects

To maximize power for the GWAS, we developed a method to estimate treatment effects from all available information (van den Oord et al. 2009) using mixed modeling (Searle et al. 1992; Goldstein, 1995). Our method first determines the optimal functional form of over-time drug response, then screens many possible covariates to select those that improve the precision of the treatment effect estimates, and finally generates the individual treatment effect estimates based on the best-fitting model using best linear unbiased predictors (BLUPs; Pinheiro & Bates, 2000). As this approach takes advantages of all available information in STAR*D, it results in more precise estimates than traditional approaches that estimate treatment effects using only two assessments (e.g. subtracting pre- from post-treatment observations).

Specifically, to determine the optimal model of overtime drug response for each side-effect outcome, we fit a series of models specifying linear change for a given number of days on drug and flat thereafter. This series began with a model assuming that maximal drug response was achieved at day 1. Each subsequent model specified an incrementally longer duration until maximal drug response was achieved, with the final model assuming that the drug effect did not plateau (i.e. linear change throughout the trial). The function produced by the log likelihoods of this series was then optimized to determine the best estimate of the average number of days until maximal drug response. This duration varied across side-effect outcomes with dizziness plateauing earliest (36 days on drug), and sexual and general side-effect burden plateauing latest (130 and 137 days on drug respectively).

After determining the optimal functional form of over-time drug response, 55 covariates were screened to identify those that improved the precision of the treatment effect estimates, using a criterion based on reduction in residual error variance relative to treatment random effect variance (Adkins et al. 2011). Screened covariates consisted of trial design characteristics, sociodemographic measures, clinical information, health care access and reason for study exit. The number of selected covariates ranged from six for vision/hearing and sexual side-effects to seven for general side-effect burden and dizziness. Design characteristics and concurrent psychiatric diagnoses (particularly drug and/or alcohol abuse and hypochondriasis) were the most commonly selected covariates.

Finally, treatment effects were generated by using a unique feature of the mixed model–random effects. To elaborate briefly, the mixed model estimates two types of parameters, coefficients that describe the predictors’ average effects for the full sample (i.e. fixed effects) and deviations from the average effects for each subject (i.e. random effects). Thus, for each of the antidepressants investigated, we were able to output treatment effects as random drug effects. Intuitively, these treatment effects quantify how much each subject’s side-effect phenotype changes in response to a given drug, relative to the average effect for all subjects who took the drug. Treatment effects estimated in the manner described here have been published previously, both in GWAS of the STAR*D data (Adkins et al. 2010) and in several CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) schizophrenia clinical trial GWAS (Aberg et al. 2010b; Adkins et al. 2011; McClay et al. 2011a, b).

Genotyping, quality control, and ancestral background

Details of the STAR*D genotyping and quality control methods have been described previously (Garriock et al. 2010). In brief, approximately half the sample was genotyped on the Affymetrix Human Mapping 500k Array Set, and the other half was genotyped using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human Array 5.0. Both versions genotype the same set of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), the only difference being that the later 5.0 version accomplishes this with a single microarray rather than a set of two arrays. SNPs with minor allele frequencies <1% or call rates <95% were excluded. We included individuals regardless of race/ethnicity and thus did not test for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium within specific ethnic groups. PLINK (Purcell et al. 2007) was used to identify 89 potential genotype–clinical sex disagreements, which were excluded from analysis. Although the sex disagreement default settings are very conservative, this ensures that no unambiguous data are included in the statistical analysis. In total, we analyzed 421 789 SNPs from 1439 subjects with a successful genotyping rate of 99.6%.

Association testing and false discovery rate (FDR) control

All association testing was conducted in PLINK (Purcell et al. 2007) using a linear regression model with five population stratification multidimensional scaling (MDS) dimensions as covariates to control for ancestry. We used an FDR-based approach (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) to declare significance. In comparison to controlling a family-wise error rate (e.g. Bonferroni correction), FDR (a) provides a better balance between finding true effects versus controlling false discoveries, (b) results in comparable standards for declaring significance across studies because it does not depend directly on the number of tests, and (c) is relatively robust against having correlated tests (Brown & Russell, 1997). FDR is commonly used in many high-dimensional applications and has been successfully applied in the context of GWAS (Lei et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2009; Beecham et al. 2009). We set an FDR threshold of 0.05 for declaring genome-wide significance and 0.10 for declaring suggestive findings. This means that, on average, 5% of the SNPs declared significant are expected to be false discoveries. Operationally (Black, 2004), FDR was controlled using q values, which are FDRs calculated using the p value of the markers as thresholds for declaring significance (Storey, 2003; Storey & Tibshirani, 2003), and can be described as:

where π0 is an estimate of the proportion of null associations, p is the observed p value, P is a random normally distributed variable, H0 is the null hypothesis that the SNP–side-effect association β = 0, and H1 is the alternative hypothesis that β ≠ 0. Thus, the numerator equals the product of the proportion of null associations × the observed p value; and the denominator is the weighted sum of the probability of obtaining a test statistic at least as extreme as the one observed, given the null hypothesis, and of the probability of obtaining a test statistic at least as extreme as the one observed given the alternative hypothesis, weighted by the proportion of null associations (see Storey, 2003 for formal derivation). Although π0 may be empirically estimated, we have assumed the most conservative value π0 = 1; thus the formula simplifies to the observed p value divided by the probability of obtaining a test statistic at least as extreme as the one observed given the null hypothesis.

For the most promising SNPs, we performed a variety of additional analyses to examine the robustness of the signal. First, we tested the SNPs separately in the subjects who self-identified as European American (EA) only and African American (AA) only. Next, to consider to what extent SNP effects are present in other side-effect domains, we analyzed whether genome-wide significant SNPs were associated, at less stringent significant levels (p < 0.05), for other side-effect measures. Although it is possible that SNP effects are side-effect factor specific, observing associations with multiple outcomes excludes the possibility of significant effects due to outcome-specific outliers and may be informative from a clinical perspective. In addition, for each SNP, we performed haplotype (proxy) analyses that incorporate information from other SNPs in that region. Such analyses may provide a technical validation of the single SNP result or point to a particularly informative haplotype.

Results

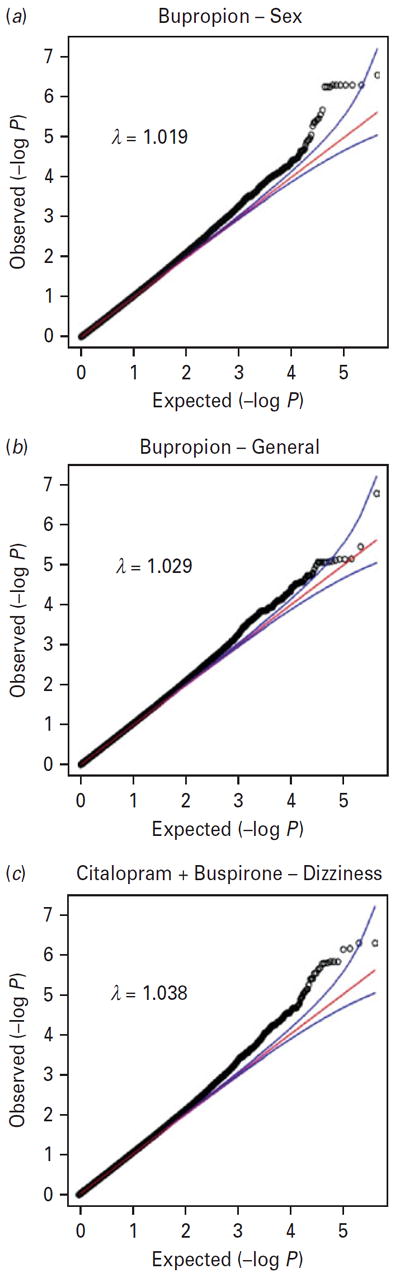

Table 2 provides details on those SNPs that were genome-wide significant (q value <0.05) and Table 3 provides details on those SNPs that were suggestive findings (0.05 < q value <0.10). The Quantile–Quantile (QQ) plots and p values for each outcome variable are available for download at www.pharmacy.vcu.edu/biomarker. Fig. 1 shows QQ plots for the top hits discussed below. The plots show that the distribution of p values from the GWAS are generally on a straight line, indicating the expected p value distribution under the null hypothesis assuming no effects of the markers. However, in each of these three plots, there is also evidence that markers in the right upper corner have p values smaller than would be expected under the null hypothesis, suggesting a true association between these markers and the outcome variable. The plots also display λ values (that is, the ratio of the median observed p value of the distribution to the expected p value under the null hypothesis) approximately equal to 1, indicating no systematic test statistic inflation.

Table 2.

Significant GWAS results with q values <0.05

| Outcome

|

Locus

|

Test

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Measure | SNPID | Gene | Chr | Psn (bp) | MAF | MA | n | p value | q value | Eff |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2742417 | SACM1L | 3 | 45706455 | 0.49 | T | 128 | 4.98 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2251954 | SACM1L | 3 | 45706788 | 0.49 | G | 128 | 4.98 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2742421 | SACM1L | 3 | 45707519 | 0.49 | G | 127 | 5.48 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2742423 | SACM1L | 3 | 45708434 | 0.49 | C | 128 | 4.98 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs1969624 | SACM1L | 3 | 45709822 | 0.49 | T | 128 | 4.98 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2673057 | SACM1L | 3 | 45710734 | 0.49 | G | 128 | 4.98 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2742431 | SACM1L | 3 | 45712125 | 0.49 | A | 127 | 5.54 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2742435 | SACM1L | 3 | 45715867 | 0.49 | G | 127 | 2.12 × 10−6 | 0.081 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2245705 | SACM1L | 3 | 45724726 | 0.49 | G | 128 | 4.98 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs2742390 | SACM1L | 3 | 45731726 | 0.45 | T | 127 | 5.43 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs7136572 | USP44 | 12 | 94483919 | 0.04 | G | 128 | 2.80 × 10−7 | 0.023 | − |

| Sertraline | General SE | rs13432159 | 2 | 67827391 | 0.08 | G | 113 | 9.00 × 10−8 | 0.038 | + | |

GWAS, Genome-wide association study; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; Chr, chromosome number; Psn, position; MAF, minor allele frequency; MA, minor allele; n, sample size; Eff, direction of the effect of minor allele; SE, side-effect.

Locus information includes Chr and location of SNP (bp, Genome Build 35). For each test, we report n, Eff, where a ‘+’ means a higher factor score, and the p and q values of the test. Shaded rows indicate SNPs in high linkage disequilibrium (LD; r2>0.8) with each other.

Table 3.

Suggestive GWAS results with q values between 0.05 and 0.10

| Outcome

|

Locus

|

Test

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Measure | SNPID | Gene | Chr | Psn (bp) | MAF | MA | n | p value | q value | EFF |

| Bupropion | General SE | rs10857636 | WDFY4 | 10 | 49655116 | 0.06 | T | 126 | 1.64 × 10−7 | 0.069 | − |

| Bupropion | Sex | rs17150687 | MAGI2 | 7 | 77881227 | 0.02 | C | 128 | 2.76 × 10−6 | 0.097 | − |

| Citalopram + Bupropion | Vision/hearing | rs10517287 | 4 | 33301097 | 0.11 | T | 160 | 1.62 × 10−7 | 0.068 | − | |

| Citalopram + Bupropion | Vision/hearing | rs17647114 | AGBL1 | 15 | 85237749 | 0.03 | T | 158 | 3.86 × 10−7 | 0.081 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs16861531 | 2 | 14315503 | 0.03 | G | 152 | 6.90 × 10−7 | 0.069 | + | |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs6795349 | CHL1 | 3 | 147477 | 0.03 | G | 149 | 2.28 × 10−6 | 0.080 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs491376 | 4 | 12725860 | 0.01 | C | 150 | 1.58 × 10−6 | 0.069 | + | |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs573332 | 4 | 12731633 | 0.11 | G | 152 | 1.47 × 10−6 | 0.069 | + | |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs2163287 | ZDHHC14 | 6 | 157961271 | 0.02 | A | 151 | 2.84 × 10−6 | 0.087 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs7015622 | 8 | 84066369 | 0.01 | C | 152 | 1.47 × 10−6 | 0.069 | + | |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs7016317 | 8 | 84066573 | 0.01 | G | 152 | 1.47 × 10−6 | 0.069 | + | |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs10988449 | C9orf50 | 9 | 131410181 | 0.17 | T | 152 | 2.90 × 10−6 | 0.087 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs8039808 | DTWD1 | 15 | 47727138 | 0.06 | A | 152 | 4.92 × 10−7 | 0.069 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs10519235 | DTWD1 | 15 | 47733664 | 0.06 | T | 152 | 4.92 × 10−7 | 0.069 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs10519238 | DTWD1 | 15 | 47756591 | 0.05 | T | 152 | 7.19 × 10−7 | 0.069 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs2034588 | 16 | 8269328 | 0.02 | G | 152 | 1.64 × 10−6 | 0.069 | + | |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs12157904 | LGALS2 | 22 | 36311958 | 0.07 | G | 152 | 2.11 × 10−6 | 0.080 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | Dizziness | rs16990008 | DMD | 23 | 31925297 | 0.02 | C | 152 | 1.60 × 10−6 | 0.069 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | General SE | rs527430 | FOXD2 | 1 | 47691408 | 0.39 | G | 152 | 3.52 × 10−7 | 0.074 | + |

| Citalopram + Buspirone | General SE | rs17766217 | POU5F1B | 8 | 128573679 | 0.01 | A | 151 | 2.52 × 10−7 | 0.074 | + |

| Sertraline | General SE | rs6724422 | 2 | 67830292 | 0.06 | T | 113 | 3.74 × 10−7 | 0.079 | + | |

| Venlafaxine | Dizziness | rs11949289 | 5 | 28375930 | 0.42 | T | 135 | 2.19 × 10−7 | 0.092 | + | |

GWAS, Genome-wide association study ; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; Chr, chromosome number; Psn, position ; MAF, minor allele frequency ; MA, minor allele; n, sample size; Eff, direction of the effect of minor allele ; SE, side-effect.

Locus information includes Chr and location of SNP (bp, Genome Build 35). For each test, we report n, Eff, where a ‘+’ means a higher factor score, and the p and q values of the test. Shaded rows indicate SNPs in high linkage disequilibrium (LD; r2>0.8) with each other.

Fig. 1.

Quantile–Quantile (QQ) plots for three outcomes showing strong association in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) results.

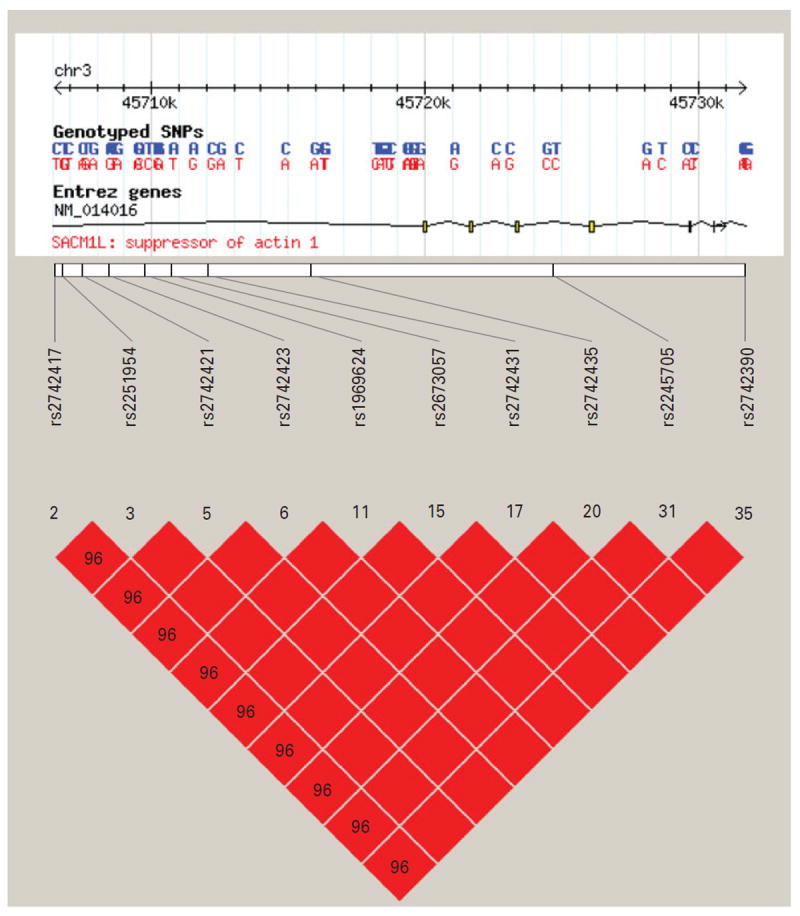

The top significant findings include a cluster of 10 SNPs spanning ~25 kb on chromosome 3, as highlighted in gray in Table 2. All 10 SNPs were situated within the boundary of the gene SACM1L, and were found to moderate bupropion’s effect on sexual adverse reactions. Because there were multiple signals located close to one another in this gene, Haploview (Barrett et al. 2005) was used to visualize the linkage disequilibrium (LD). In Fig. 2, which shows the LD heat map for the 10 significant SNPs, we can see that all 10 SNPs are in very high LD with one another, with the lowest r2 value being 0.96. This suggests that they represent a single signal. To see the LD structure in the region around the 10 significant SNPs, we incorporated HapMap Version 3, Release 2 (International HapMap Consortium, 2005) with our data in our LD visualization as it includes finer mapping of this region than was done in the STAR*D sample. First, we examined the entire region encompassed by rs2742390 and rs2742417, the two extreme SNPs of the SACM1L hits in Table 2, ± 100 kb of flanking sequence. We saw high LD in the region, for example r2 > 0.80 from 45692 to 45767 kb (see online Supplementary Fig. S1), which implies that the causal variant could potentially be much further away from the SNPs indicated here.

Fig. 2.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) heat map for 10 significant SACM1L gene findings. Heat maps depict the D′ for each pair of SNPs with white and blue indicating D′=0; shades of pink indicating 0<D′<1, with darker shades of pink indicating larger values of D′; and red indicating D′=1. Higher values of Dk indicate higher LD, with D′=1 indicating perfect LD. The figure displays the 10 SNPs in the gene SACM1L that were significant at the q < 0.10 threshold. The numbers in each cell represent the pairwise D′ value and an empty cell means the pairwise D′ =1, which indicates that the pair of SNPs is in perfect LD.

Suggestive findings in Table 3 involved bupropion and citalopram + buspirone respectively. The first involved rs17150687 on chromosome 7q21.1 (p value = 2.76 × 10−6, q value = 0.097) located within an intron of the gene MAGI2, which has a moderating effect between bupropion and sexual side-effects. The second involved rs6795349 on chromosome 3p26.3 (p value = 2.28 × 10−6, q value = 0.080), 60 kb away from the gene CHL1, which has a moderating effect between citalopram + buspirone and dizziness. Both of these signals had low minor allele frequency (MAF; 0.017 and 0.035 respectively) and were not in LD with any nearby SNPs. Given the reduced confidence due to low MAF and the lack of proxies to confirm the robustness of the signals, these two associations should be viewed only as suggestive.

Another suggestive SNPs in Table 3 is rs10857636 (p value = 1.64 × 10−7, q value = 0.069) on chromosome 10q11.2 located within an intron of the gene WDFY4, which moderates the effects between bupropion and general side-effect burden. Haplotype analysis did not improve the association signal in these findings presented here, except where noted earlier.

Discussion

To maximize the benefit of antidepressant therapy to the individual patient, not only should the most efficacious drug be prescribed at the time of first presentation but also the drug with the minimal side-effect profile. Understanding individual differences in the development of side-effects following antidepressant therapy is therefore essential to personalizing the treatment of depression. In this study, we performed GWAS on four side-effect factors including general side-effect burden, sexual adverse reactions, dizziness, and vision/hearing related side-effects. We detected 34 SNPs that, according to our pre-identified criteria (FDR controlled at 0.1 level), can be considered genome-wide significant or suggestive.

Our top findings involved 10 hits within the gene SACM1L, which negatively moderated the effect of the minor allele between bupropion and sexual side-effects. The phosphatidylinositide phosphatase SAC1 is encoded by the SACM1L gene. SAC1 is an integral membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus (Rohde et al. 2003) that plays a direct role in the growth factor signaling in both organelles and the Golgi trafficking (Blagoveshchenskaya et al. 2008). Previous studies have shown that mutations in the SACM1L gene alter SAC1 enzymatic activity and organelle localization (Liu et al. 2008b). Disruptions in the cellular secretory machinery alter hormone and neurotransmitter secretion, which may lead to sexual dysfunction (Corona & Maggi, 2010). A MAGI2 SNP was the second top hit significantly associated with sexual side-effects during bupropion treatment. MAGI2 plays a role in neuronal migration and protein–protein interactions (Wright et al. 2004; Deng et al. 2006), further suggesting that alterations in cellular trafficking may be associated with sexual side-effects during bupropion treatment. Of considerable interest is the report in a recent study (Berger et al. 2011) that MAGI2 polymorphisms have been associated with prostate cancer, which is closely related to spermatogenesis.

For the SACM1L and MAGI2 findings, the minor allele effects were negative, suggesting a reduction in sexual side-effects during bupropion treatment for patients with these polymorphisms. As bupropion is widely known for its almost complete lack of sexual side-effects (Serretti & Chiesa, 2009), this initially counterintuitive finding requires further interpretation. Given that patients were taking a different antidepressant immediately prior to switching to bupropion, the effect we are observing is likely to reflect the presence of a protective polymorphism, which facilitates rebound from antidepressant-induced sexual side-effects, and perhaps generally increases libido, both of which are documented effects of bupropion in subgroups of subjects (Modell et al. 2000; Clayton et al. 2004). Our association findings implicating these genes as a moderator of sexual function during bupropion treatment, in addition to functional evidence indicating sexual dysfunction, make these genes compelling candidates for additional investigation.

Two genes that are among the suggestive hits in our results (Table 3) have been associated with psychiatric-related phenotypes in previous studies, but the gene function of each is unknown. Expression of the CHL1 gene, associated with dizziness during citalopram + buspirone treatment, has previously been found to be lower in a patient group with high paroxetine sensitivity (Morag et al. 2011), and CHL1 polymorphisms have also been associated with schizophrenia (Sakurai et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2005). The WDFY4 gene, associated with general side-effect burden during bupropion treatment in our study, has previously been implicated in successful smoking cessation therapy using bupropion (Uhl et al. 2008). Given the current lack of information about these genes, no firm conclusions about the biological mechanisms underlying their putative drug–side-effect interaction can be drawn.

Currently, it is premature to suggest direct clinical applications of these findings for prescribing antidepressants. However, once the effects of these genes are replicated and the most useful variants identified, we can envision possible ways they might be applied. For example, bupropion has been supported in clinical trials as an adjunct treatment for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (Demyttenaere & Jaspers, 2008; Safarinejad, 2010), with no information available to identify potential respondents. For those patients who need to stay on an SSRI because of its therapeutic efficacy for major depression or an anxiety disorder, polymorphisms in genes such as SACM1L and MAGI2 might be used to predict who could benefit from such trials. Similarly, some psychiatrists add buspirone to an SSRI such as citalopram, not only to potentially augment the antidepressant effects of the latter, as was intended in STAR*D, but also to treat co-occurring anxiety symptoms not adequately relieved with monotherapy (Harvey & Balon, 1995). As this increases the risk of side-effects such as dizziness, genotyping variants in a gene such as CHL1 might help to select patients who would tolerate such combination therapy.

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of two potential limitations. First, the assessment of side-effects is based on patient self-report in currently depressed individuals, which may upwardly bias the report of physical symptoms. Second, patients included in STAR*D were not drug-naïve at the start of the study, and patients in this analysis had previously participated in earlier STAR*D treatment levels, so some of the effects seen here may not be the result of the patients initiating treatment with a new drug regimen. Rather, it is possible that some of the observed genetic moderation of side-effects may in fact be genetic moderation of withdrawal or ‘washout’ for the immediately preceding therapy. Although we have discussed this possibility in scenarios in which it is likely, there is no way to analytically adjudicate between withdrawal versus side-effects to newly initiated treatment, given the STAR*D study design. This limitation highlights the need for future pharmacogenomic studies of antidepressant medications focused on drug-naïve patients, so as to more fully isolate the effects of individual antidepressants and, thus, strengthen analytical inference.

As with any genetic associations, our findings will require replication and functional validation. We are currently unable to replicate our findings in an independent sample because of the lack of available data sets that are comparable to the unique multistage design of the STAR*D study. To facilitate the replication process we provide all p values (www.pharmacy.vcu.edu/biomarker) as a resource for investigators with the requisite samples to carry out replication. However, the present study shows the potential of GWAS to discover genes and pathways that moderate adverse effects of antidepressant medication. A better understanding of these mechanisms and the role of specific polymorphisms may eventually help to personalize antidepressant medication so as to minimize adverse drug reactions for patients with depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant DA026119.

Footnotes

Supplementary material accompanies this paper on the Journal’s website (http://journals.cambridge.org/psm).

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Aberg K, Adkins DE, Bukszar J, Webb BT, Caroff SN, Miller DD, Sebat J, Stroup S, Fanous AH, Vladimirov VI, McClay JL, Lieberman JA, Sullivan PF, van den Oord EJ. Genomewide association study of movement-related adverse antipsychotic effects. Biological Psychiatry. 2010a;67:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberg K, Adkins DE, Liu Y, McClay JL, Bukszar J, Jia P, Zhao Z, Perkins D, Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, Sullivan PF, van den Oord EJ. Genome-wide association study of antipsychotic-induced QTc interval prolongation. Pharmacogenomics Journal. 2010b doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.76. Published online: 5 October 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins DE, Aberg K, McClay JL, Bukszar J, Zhao Z, Jia P, Stroup TS, Perkins D, McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Sullivan PF, van den Oord EJ. Genomewide pharmacogenomic study of metabolic side effects to antipsychotic drugs. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011;16:321–332. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins DE, Aberg K, McClay JL, Hettema JM, Kornstein SG, Bukszar J, van den Oord EJ. A genomewide association study of citalopram response in major depressive disorder – a psychometric approach. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:e25–e27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008;322:881–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1156409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala ME. Brain serotonin, psychoactive drugs, and effects on reproduction. Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;9:258–276. doi: 10.2174/187152409789630389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbee JG. Mixed symptoms and syndromes of anxiety and depression: diagnostic, prognostic, and etiologic issues. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;10:15–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1026198512361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecham GW, Martin ER, Li YJ, Slifer MA, Gilbert JR, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. Genome-wide association study implicates a chromosome 12 risk locus for late-onset Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2009;84:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berger MF, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Drier Y, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, Sboner A, Esgueva R, Pflueger D, Sougnez C, Onofrio R, Carter SL, Park K, Habegger L, Ambrogio L, Fennell T, Parkin M, Saksena G, Voet D, Ramos AH, Pugh TJ, Wilkinson J, Fisher S, Winckler W, Mahan S, Ardlie K, Baldwin J, Simons JW, Kitabayashi N, Macdonald TY, Kantoff PW, Chin L, Gabriel SB, Gerstein MB, Golub TR, Meyerson M, Tewari A, Lander ES, Getz G, Rubin MA, Garraway LA. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MA. A note on the adaptive control of false discovery rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B. 2004;66:297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Blagoveshchenskaya A, Cheong FY, Rohde HM, Glover G, Knodler A, Nicolson T, Boehmelt G, Mayinger P. Integration of Golgi trafficking and growth factor signaling by the lipid phosphatase SAC1. Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;180:803–812. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. Wiley; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BW, Russell K. Methods correcting for multiple testing: operating characteristics. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16:2511–2528. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971130)16:22<2511::aid-sim693>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull SA, Hu XH, Hunkeler EM, Lee JY, Ming EE, Markson LE, Fireman B. Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants: influence of patient-physician communication. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002a;288:1403–1409. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.11.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull SA, Hunkeler EM, Lee JY, Rowland CR, Williamson TE, Schwab JR, Hurt SW. Discontinuing or switching selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2002b;36:578–584. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun E, Caillier SJ, Montalban X, Villoslada P, Fernandez O, Brassat D, Comabella M, Wang J, Barcellos LF, Baranzini SE, Oksenberg JR. Genome-wide pharmacogenomic analysis of the response to interferon beta therapy in multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 2008;65:337–344. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QY, Chen Q, Feng GY, Lindpaintner K, Chen Y, Sun X, Chen Z, Gao Z, Tang J, He L. Case-control association study of the close homologue of L1 (CHL1) gene and schizophrenia in the Chinese population. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;73:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AH, Warnock JK, Kornstein SG, Pinkerton R, Sheldon-Keller A, McGarvey EL. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion SR as an antidote for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:62–67. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona G, Maggi M. The role of testosterone in erectile dysfunction. Nature Reviews Urology. 2010;7:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Albert A, Mesters P, Dewe W, De Bruyckere K, Sangeleer M. What happens with adverse events during 6 months of treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:859–863. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Jaspers L. Review: bupropion and SSRI-induced side effects. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2008;22:792–804. doi: 10.1177/0269881107083798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng F, Price MG, Davis CF, Mori M, Burgess DL. Stargazin and other transmembrane AMPA receptor regulating proteins interact with synaptic scaffolding protein MAGI-2 in brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:7875–7884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1851-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchini L, Serretti A, Gasperini M, Smeraldi E. Familial concordance of fluvoxamine response as a tool for differentiating mood disorder pedigrees. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1998;32:255–259. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(98)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost J, Sandvik P, Spigset O. Sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressants [in Norwegian] Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening. 2010;130:1930–1931. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.10.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriock HA, Kraft JB, Shyn SI, Peters EJ, Yokoyama JS, Jenkins GD, Reinalda MS, Slager SL, McGrath PJ, Hamilton SP. A genomewide association study of citalopram response in major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H. Multilevel Statistical Models. Arnold; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey KV, Balon R. Augmentation with buspirone: a review. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 1995;7:143–147. doi: 10.3109/10401239509149042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International HapMap Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Serretti A. Review and meta-analysis of antidepressant pharmacogenetic findings in major depressive disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15:473–500. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchheiner J, Nickchen K, Bauer M, Wong ML, Licinio J, Roots I, Brockmoller J. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressants and antipsychotics: the contribution of allelic variations to the phenotype of drug response. Molecular Psychiatry. 2004;9:442–473. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavedan C, Licamele L, Volpi S, Hamilton J, Heaton C, Mack K, Lannan R, Thompson A, Wolfgang CD, Polymeropoulos MH. Association of the NPAS3 gene and five other loci with response to the antipsychotic iloperidone identified in a whole genome association study. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:804–819. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei SF, Yang TL, Tan LJ, Chen XD, Guo Y, Guo YF, Zhang L, Liu XG, Yan H, Pan F, Zhang ZX, Peng YM, Zhou Q, He LN, Zhu XZ, Cheng J, Liu YZ, Papasian CJ, Deng HW. Genome-wide association scan for stature in Chinese: evidence for ethnic specific loci. Human Genetics. 2009;125:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0590-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, Bowman L, Heath S, Matsuda F, Gut I, Lathrop M, Collins R. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy – a genomewide study. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:789–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Batliwalla F, Li W, Lee A, Roubenoff R, Beckman E, Khalili H, Damle A, Kern M, Furie R, Dupuis J, Plenge RM, Coenen MJ, Behrens TW, Carulli JP, Gregersen PK. Genome-wide association scan identifies candidate polymorphisms associated with differential response to anti-TNF treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Molecular Medicine. 2008a;14:575–581. doi: 10.2119/2008-00056.Liu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Boukhelifa M, Tribble E, Morin-Kensicki E, Uetrecht A, Bear JE, Bankaitis VA. The Sac1 phosphoinositide phosphatase regulates Golgi membrane morphology and mitotic spindle organization in mammals. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2008b;19:3080–3096. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YZ, Guo YF, Wang L, Tan LJ, Liu XG, Pei YF, Yan H, Xiong DH, Deng FY, Yu N, Zhang YP, Zhang L, Lei SF, Chen XD, Liu HB, Zhu XZ, Levy S, Papasian CJ, Drees BM, Hamilton JJ, Recker RR, Deng HW. Genome-wide association analyses identify SPOCK as a key novel gene underlying age at menarche. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5:e1000420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Equation Analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox JC, Levi M, Thompson C. The compliance with antidepressants in general practice. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1994;8:48–53. doi: 10.1177/026988119400800108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK, Murphy GM, Jr, Kennedy JL. Pharmacogenetics of psychotropic drug response. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:780–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClay JL, Adkins DE, Aberg K, Bukszar J, Khachane AN, Keefe RS, Perkins DO, McEvoy JP, Stroup TS, Vann RE, Beardsley PM, Lieberman JA, Sullivan PF, van den Oord EJ. Genome-wide pharmacogenomic study of neurocognition as an indicator of antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011a;36:616–626. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClay JL, Adkins DE, Aberg K, Stroup S, Perkins DO, Vladimirov VI, Lieberman JA, Sullivan PF, van den Oord EJ. Genome-wide pharmacogenomic analysis of response to treatment with antipsychotics. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011b;16:76–85. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ. High medication discontinuation rates in psychiatry: how often is it understandable? Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;26:109–112. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000205845.36042.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modell JG, May RS, Katholi CR. Effect of bupropion-SR on orgasmic dysfunction in nondepressed subjects: a pilot study. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2000;26:231–240. doi: 10.1080/00926230050084623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morag A, Pasmanik-Chor M, Oron-Karni V, Rehavi M, Stingl JC, Gurwitz D. Genome-wide expression profiling of human lymphoblastoid cell lines identifies CHL1 as a putative SSRI antidepressant response biomarker. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12:171–184. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus User’s Guide. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Oreilly RL, Bogue L, Singh SM. Pharmacogentic response to antidepressants in a multicase family with affective disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1994;36:467–471. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)90642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI, Fava M. Does the probability of receiving placebo influence clinical trial outcome? A meta-regression of double-blind, randomized clinical trials in MDD. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare CMB, Mack JW. Differentiation of two genetically specific types of depression by response to antidepressant drugs. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1971;8:306–309. doi: 10.1136/jmg.8.3.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-Plus. Springer; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack MH, Reiter S, Hammerness P. Genitourinary and sexual adverse effects of psychotropic medication. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1992;22:305–327. doi: 10.2190/P60R-PLED-TL09-TUEN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcelli S, Drago A, Fabbri C, Gibiino S, Calati R, Serretti A. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressant response. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2011;36:87–113. doi: 10.1503/jpn.100059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, De Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Rae DS, Narrow WE, Kaelber CT, Schatzberg AF. Prevalence of anxiety disorders and their comorbidity with mood and addictive disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;34(Suppl):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde HM, Cheong FY, Konrad G, Paiha K, Mayinger P, Boehmelt G. The human phosphatidylinositol phosphatase SAC1 interacts with the coatomer I complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:52689–52699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Trivedi MH, Sackeim HA, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Quitkin FM, Kashner TM, Kupfer DJ, Rosenbaum JF, Alpert J, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Lebowitz BD, Ritz L, Niederehe G. Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2004;25:119–142. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safarinejad MR. The effects of the adjunctive bupropion on male sexual dysfunction induced by a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor: a double-blind placebo-controlled and randomized study. British Journal of Urology International. 2010;106:840–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai K, Migita O, Toru M, Arinami T. An association between a missense polymorphism in the close homologue of L1 (CHL1, CALL) gene and schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7:412–415. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle SR, Casella G, McCulloch CE. Variance Components. Wiley; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Segraves RT. Effects of psychotropic drugs on human erection and ejaculation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:275–284. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810030081011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;29:259–266. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a5233f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I, Bailer U, Bollen J, Demyttenaere K, Kasper S, Lecrubier Y, Montgomery S, Serretti A, Zohar J, Mendlewicz J. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: results from a European multicenter study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68:1062–1670. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey J. The positive false discovery rate: a Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Annals of Statistics. 2003;31:2013–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Liu QR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Walther D, Rose JE, David SP, Niaura R, Lerman C. Molecular genetics of successful smoking cessation: convergent genome-wide association study results. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:683–693. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Oord EJ, Adkins DE, McClay J, Lieberman J, Sullivan PF. A systematic method for estimating individual responses to treatment with antipsychotics in CATIE. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;107:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ, Balasubramani GK, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA. Self-rated global measure of the frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2006;12:71–79. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright GJ, Leslie JD, Ariza-McNaughton L, Lewis J. Delta proteins and MAGI proteins: an interaction of Notch ligands with intracellular scaffolding molecules and its significance for zebrafish development. Development. 2004;131:5659–5669. doi: 10.1242/dev.01417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zobel A, Maier W. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressive treatment. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2010;260:407–417. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.