Abstract

Introduction and Background

The arsenal of interventions to reduce the disproportionate rates of HIV and sexually transmitted disease (STD) infection among Latinos in the United States lags behind what is available for other populations. The purpose of this project was to develop an intervention that builds on existing community strengths to promote sexual health among immigrant Latinas.

Methods

Our community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership engaged in a multistep intervention development process. The steps were to (1) increase Latina participation in the existing partnership, (2) establish an intervention team, (3) review the existing sexual health literature, (4) explore health-related needs and priorities of Latinas, (5) narrow priorities based on what is important and changeable, (6) blend health behavior theory with Latinas’ lived experiences, (7) design an intervention conceptual model, (8) develop training modules and (9) resource materials, and (10) pretest and (11) revise the intervention.

Results

The MuJEReS intervention contains five modules to train Latinas to serve as lay health advisors (LHAs) known as “Comadres.” These modules synthesize locally collected data with other local and national data, blend health behavior theory with the lived experiences of immigrant Latinas, and harness a powerful existing community asset, namely, the informal social support Latinas provide one another.

Conclusion

This promising intervention is designed to meet the sexual health priorities of Latinas. It extends beyond HIV and STDs and frames disease prevention within a sexual health promotion framework. It builds on the strong, preexisting social networks of Latinas and the preexisting, culturally congruent roles of LHAs.

Introduction and Background

Despite continued efforts aimed at preventing transmission, HIV/AIDS remains a global epidemic. In the United States approximately 56,000 new HIV infections occur each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008a). Although this number has not changed significantly over time, the percentage of people infected in vulnerable groups (e.g., racial and sexual minorities) continues to increase. Currently, Latinas comprise nearly one quarter of all new HIV infections among U.S. Latinos, and HIV/AIDS is the fourth leading cause of death among Latinas ages 35 to 44 years old (CDC, 2009). Rates of reportable sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) also are higher among Latinos than among non-Latino Whites. Subpopulation estimates have shown that incidence rates for Latinas were 3.8 times the rates among White females (CDC, 2008b).

HIV and STD risk among Latinas is often related to their male partners having multiple sexual partners (Gonzalez, Hendriksen, Collins, Duran, & Safren, 2009; Hirsch, Higgins, Bentley, & Nathanson, 2002) and inconsistent condom use (Knipper et al., 2007; Marin, Gomez, & Tschann, 1993; Organista, Organista, Bola, Garcia de Alba, & Castillo Moran, 2000). Immigrant Latinas from Mexico and Central America typically report few sexual partners and low levels of injecting-drug use compared with Puerto Rican Latinas and other women (CDC, 2008a; Gonzalez et al., 2009). However, Latinas tend to have low knowledge of pregnancy and disease prevention strategies and are less likely to use contraception compared with non-Latina women.

North Carolina is within the top 10 U.S. states with the highest HIV and STD infection rates. In 2007, HIV incidence rates in North Carolina were 40% higher than the national rate, and HIV and STD infection rates for Latinos in the state were three and four times that of non-Latino Whites (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2008a, 2008b). Data suggest that Spanish-speaking Latinos in North Carolina are disproportionately at risk for HIV compared with their English-speaking Latino and non-Latino counterparts. According to the North Carolina Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, Spanish-speaking Latinas were less likely to report using a condom at most recent intercourse, seeking or accessing health services (e.g., prevention services), or having a personal doctor and health insurance when compared with non-Latina women or English-speaking Latinas (North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics, 2006).

Between 2000 and 2008, the North Carolina population increased by 14.6%, whereas the Latino population increased 51.8% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). About half of North Carolina Latinos live in rural communities. These communities tend to be ill equipped to provide culturally congruent health education and healthcare services (Kasarda & Johnson, 2006; North Carolina Institute of Medicine, 2003; Rhodes et al., 2007). In addition to the chronic lack of resources available in these areas, half of Latinos in the state are uninsured, and 40% live in poverty (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

Many Latinas are hesitant to utilize the few resources that are available, being particularly fearful of discrimination based on ethnicity (Organista, Carrillo, & Ayala, 2004; Zambrana, Cornelius, Boykin, & Lopez, 2004). They also report anxiety related to accessing care owing to inexperience navigating a healthcare system that is very different from healthcare services in their countries of origin (Gurman & Becker, 2008; Organista et al., 2004; Vissman et al., 2011).

Perceptions about gender roles (e.g., “machismo” and “marianismo” [a cultural ideal of female modesty, submissiveness, virtue, and sexual purity]) also pose barriers to education and open communication about risks of HIV and STD infection (Amaro & Raj, 2000; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Griffith, et al., 2009). The majority of Latinos now immigrating to rural southeastern United States, and North Carolina in particular, arrive from Central America and southern Mexico and have lower educational backgrounds than those who historically immigrated from northern and central Mexico (Kasarda & Johnson, 2006; Southern State Directors Work Group, 2008). They have little knowledge of, and hold widespread misconceptions about, HIV and STDs. These complex and interrelated barriers undermine communication about needs, utilization of resources, and, therefore, equitable access to outreach and care, especially for Latinas for whom agency is not culturally affirmed.

The current political arguments surrounding immigration and deportation policies only serve to increase perceived discrimination and/or risk of deportation, and thus alienate Latinos from accessing healthcare services for which they are eligible (Rhodes et al., 2007; Vissman et al., 2011). Yet, as the HIV incidence rate continues to rise among this population, so too does the urgency to develop, implement, and evaluate culturally congruent HIV prevention interventions.

The goal of the Mujeres Juntas Estableciendo Relaciones Saludables (MuJEReS; Women United Establishing Healthy Relationships) intervention is to reduce the risk of HIV and STD infection among Spanish-speaking, recently arrived, and less-acculturated Latinas who are settling in the rural Southeast. Developed using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodology, the MuJEReS intervention includes the systematic selection, careful training, and ongoing support of Latinas to serve as lay health advisors (LHAs).We describe the systematic development of the intervention through the expansion of the CBPR partnership; the integration of formative data, theoretical considerations, and findings from the literature; and the content of the intervention.

Methods

The MuJEReS intervention was developed in response to Latinas’ expressed need for an HIV prevention intervention for women during the implementation of CBPR partnership-initiated programming for Latino men. Wives, sisters, female cousins, and girlfriends of intervention participants came to intervention sessions to request programming for themselves (Cashman, Eng, Simán, & Rhodes, 2011; Rhodes, in press). The CBPR partnership intended to be responsive to these community-initiated requests and aimed to ensure that any intervention developed for Latinas met their needs and priorities and was developed in authentic partnership with Latina community members. The CBPR partnership is committed to partnership with those closest to the health phenomenon to ensure more informed understanding and thus more impactful action (Rhodes, in press; Rhodes & Benfield, 2006; Rhodes et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2011; Rhodes, Malow, & Jolly, 2010).

The CBPR partnership used an 11-step process to develop the intervention that builds upon the methodology used to create the HoMBReS intervention for Latino men (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Montano, et al., 2006). The HoMBReS intervention has been found to be efficacious (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Bloom, Leichliter, & Monta~no, 2009) and was the first community-level HIV prevention intervention to meet the criteria of “best evidence” (CDC, 2011). These 11 Steps are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Steps in Developing the MuJEReS Intervention

| Step | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Expand partnership | Increased number of Latinas participating in the existing CBPR partnership |

| Step 2: Establish Intervention Team | Established a subgroup to serve as an initial workgroup that evolved into an Intervention Team |

| Step 3: Review of existing sexual health literature | Identified and reviewed the current available literature about risk and sexual health promotion for Latinas; initiated creative thinking about the intervention to build on the state of both the science and practice of sexual health promotion among Latinas |

| Step 4: Explore health-related needs and priorities | Conducted focus groups with Latina women and examined available, locally collected data from other sources |

| Step 5: Refine and narrow intervention priorities | Narrowed priorities based on 2 key questions: How important is each need? and How changeable is each need? |

| Step 6: Blend health behavior theory with the lived experiences of community members | Operationalized theory; selected social cognitive theory and empowerment education as culturally congruent theoretical bases and LHA as a culturally congruent implementation strategy |

| Step 7: Design an intervention conceptual model | Identified intervention priorities, intervention-specific roles of LHAs (i.e., Comadres), and outcomes |

| Step 8: Develop intervention training modules | Prepared intervention goals, objectives, and key messages; and developed intervention activities and materials based on underlying theoretical constructs and Latinas’ lived experiences |

| Step 9: Develop materials | Prepared MuJEReS Training Manual to train Comadres, the Comadre Resource Manual for Comadre referral during implementation, and all other materials (e.g., brochures) |

| Step 10: Pretest the intervention | Pretested the intervention |

| Step 11: Revise the intervention | Revised the intervention based on pretest results |

Step 1: Expand Partnership

The partnership had regular meetings that included lay community members (including Latinas), organizational representatives, local business owners, and academic researchers (Rhodes et al., 2011); however, few Latinas regularly attended these meetings. Expanding the partnership to include more Latinas was a clear first step and was met with enthusiasm in the community. The partnership had a positive reputation in the community in part because of the commitment to inclusion, authentic shared decision making (as opposed to token representation), and member commitment to move from basic research to action (e.g., community-level interventions; Rhodes et al., 2011). Members networked with Latina community leaders to identify other Latinas who were interested in participating in the partnership. This helped to identify a core group of women who joined the partnership and comprised a workgroup to focus on Latina health. This step was completed quickly, given the existing interest of Latinas in meeting the needs of other Latinas within their community.

Step 2: Establish an Intervention Team

A subgroup of the partnership was established to serve as an Intervention Team to direct the Latina-focused effort. This workgroup was composed of nine Latina women, two Latino men, two health department representatives, three AIDS service organization representatives, and three academic researchers. The Intervention Team had the full support of the larger partnership and engaged partnership members in all aspects of the process.

Step 3: Review Existing Sexual Health Literature

The Intervention Team examined published and unpublished papers, reports, and briefs to identify what was known in terms of predictors of sexual health and sexual health-seeking behavior among Latinas in the United States. The Intervention Team also explored the limited available sexual health interventions designed for Latinas in the United States, examining the demographics of Latina participants (e.g., ages; English-, Spanish- and/or indigenous-language speaking; countries of origin; number of years living in United States); the theoretical foundations; and intervention themes, strategies, and objectives. This step initiated creative thinking about the intervention to build on the state of both the science and practice of HIV prevention among Latinas in the United States.

Step 4: Explore Health-Related Needs and Priorities of Latinas

Assisted by a Spanish-speaking graduate student, the partnership initiated a series of focus groups to examine health priorities, sociocultural determinants of sexual risk, and potentially effective intervention approaches to meet the needs and priorities of Latinas. The mean age of focus group participants was 36 years, 50% reported Mexico as their country of origin, and approximately 65% reported speaking and understanding only Spanish. The CBPR partnership identified 7 qualitative themes related to the HIV prevention and sexual health needs among Latinas and 13 themes outlining guidance for intervention approaches to meet these needs. The methodology of and findings from these focus groups have been reported elsewhere (Cashman et al., 2011).

To develop preliminary intervention priorities, members of the Intervention Team used findings from these focus groups and from other local studies conducted by the CBPR partnership, including in-depth provider interviews; a National Cancer Institute– funded intervention study known as C-CAPRELA (Cervical Cancer Prevention for Latinas); a CDC-funded study of nonmedical sources of prescription medications (Rhodes, Fernandez, et al., 2011; Vissman et al., 2011); a study of HIV-positive Latinos (Vissman, Hergenrather, et al., 2011); and Latino men’s sexual health promotion studies (Knipper et al., 2007; Rhodes, in press; Rhodes et al., 2007; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Wilkin, Alegria-Ortega, & Monta~no, 2006; Vissman et al., 2009).

Step 5: Refine and Narrow Intervention Priorities

After draft priorities were developed by this working group using a nominal group process (Becker, Israel, & Allen, 2005), five community forums were held, each with between 4 and 12 Latinas in addition to other community members, organizational leaders, and academic researchers. These forums were held in rural and urban locations, including the community center of a mobile home community, a community leader’s home, and a partner’s bridal and quinceañera business. The finalized intervention priorities included:

Increase knowledge of female and male sexual anatomy;

Increase knowledge of and dispel misconceptions about sexual health, and HIV and STDs, and their signs and symptoms, treatment, and prevention;

Offer guidance on local screenings and HIV and STD counseling, testing, care, and treatment services, eligibility requirements, and “what to expect” in healthcare encounters;

Work with women to overcome their barriers to accessing sexual health resources (e.g., transportation, immigration status, language, child care);

Improve skills for communicating about sexual health priorities and desires with partners and health providers;

Build condom use skills (e.g., how to properly select, negotiate, use, and dispose of condoms);

Build supportive relationships and sense of community among Latinas; and

Provide skills building to successfully help others.

It also was during this step that Intervention Team determined that an LHA strategy to intervention would be culturally congruent because training Latinas within the community to serve as LHAs focusing on sexual health built on what they already do for one another (e.g., sharing childcare, providing transportation, running errands, providing advice). It was identified as a natural approach to harness the strengths of Latinas as a community. The Intervention Team also concluded that “Comadre”was an appropriate title for an LHA. Comadre is defined as a “midwife,” “godmother,” “neighbor,” “friend,” and “gossip”; however, local Latinas also use the term to mean a trusted friend or neighbor who can be relied upon for advice and assistance.

Step 6: Blend Health Behavior Theory with the Lived Experiences of Latinas

Because theory is intended to explain the processes involved in behavior change, discussions of theory allowed the Intervention Team to understand the process of behavior change and identify how theory fit into Latinas’ lived experiences. This understanding helped the Intervention Team to make informed decisions about intervention strategies and activities.

Through understanding how existing interventions utilized theory, the Intervention Team determined that, in addition to the LHA approach, application of both social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and empowerment education (Freire, 1973) to the intervention strategy would be used to frame the intervention and strengthen the informal social and helping networks among Latinas, thus increasing its effectiveness. Briefly, social cognitive theory emphasizes the bidirectional influence of environmental factors (such as family environment as well as broader societal and structural factors) and personal factors (such as emotional and cognitive functioning) upon an individual’s behavior. Modeling desirable behavior to assist a person in behavioral change is also a component of this theoretical approach. The blend of modeling (via Comadres) and broad view of behavioral influence and change renders social cognitive theory an excellent fit for this intervention. In tandem with social cognitive theory, empowerment education posits that individuals must experience the process of learning, known as consciousness raising, and critical reflection to “get to” action.

Step 7: Design of an Intervention Conceptual Model

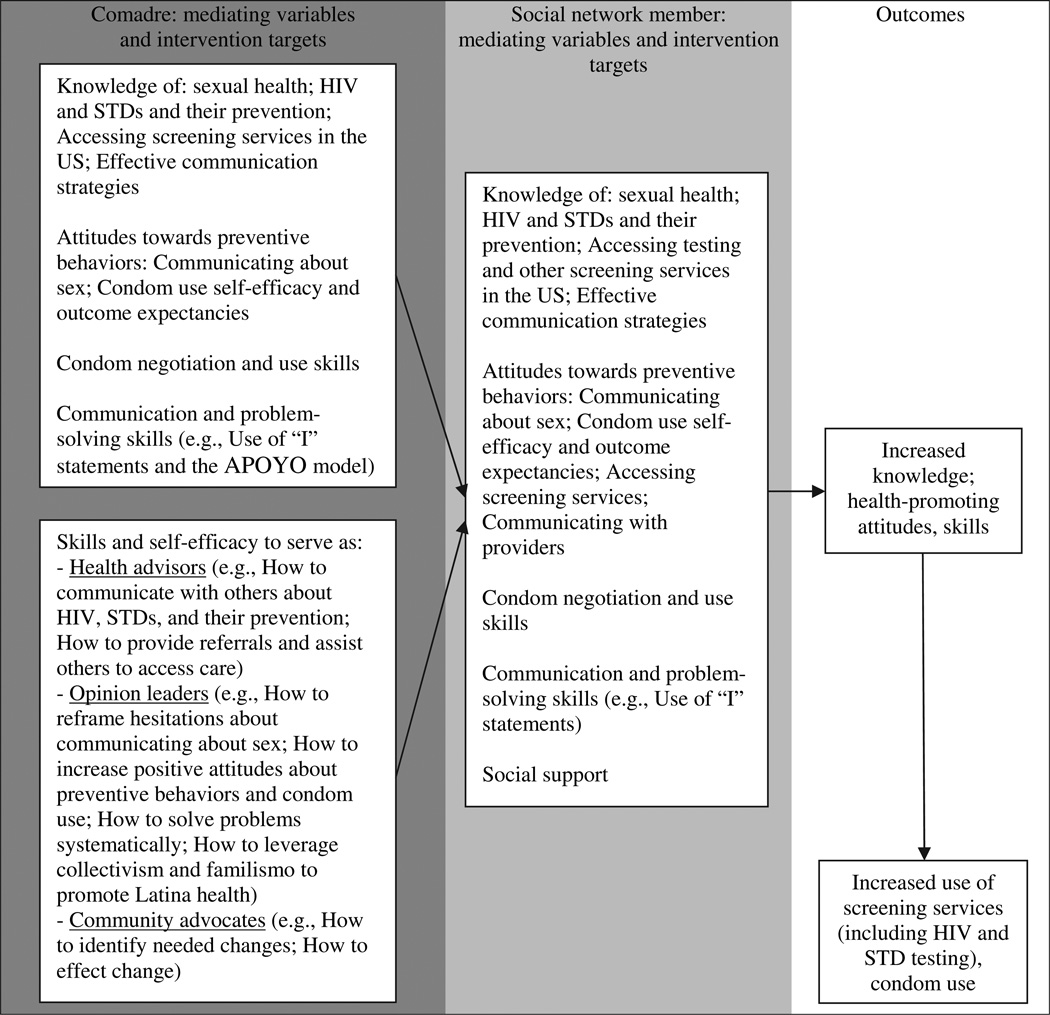

The resulting MuJEReS intervention conceptual model demonstrated how each Comadre would work to increase knowledge, health-promoting attitudes, and skills among Latinas in her community, specifically through providing information on sexual health, HIV and STDs and their prevention, how to access and ask for testing and/or treatment, strategies for partners and provider communication and sources of support, and navigation of the healthcare system. The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The MuJEReS intervention conceptual model.

Step 8: Develop Training Modules

Using the intervention conceptual model as the framework, the Intervention Team created each MuJEReS intervention module used to train Comadres. Members drafted, adapted, reviewed, and revised each session—its goal, objectives, key messages, and theoretical underpinnings, and intervention activities and materials. The process was iterative with multiple opportunities for the Intervention Team and partnership members to provide feedback. This systematic approach was designed to ensure that the intervention was based on the real-world experiences of both immigrant Latino men and women, the practice-based experiences working with the Latino community, and state-of-the-art intervention and prevention science.

Step 9: Develop Materials

After the intervention was developed, materials were created, including brochures, a low literacy, wallet-sized reminder that serves as a “cheat sheet” on how to provide support to others using the CBPR-partnership developed APOYO (help) model that stands for “poner Atención”-“Preguntar”-“Ofrecer consejo”-“Y”-“Organizar juntos los pasos siguientes” (pay attention-ask questions-offer advice-and-together organize next steps); process evaluation data collection forms that are used to document the help that Comadres provide and serve as a cue to action for Comadre activities; and other intervention activity-related materials, including role-playing scripts and film clappers. DVD segments were conceptualized and learning objectives articulated. These segments are designed to serve as triggers for discussion and role modeling to build self-efficacy and skills. These segments are linked to segments developed and delivered for sexually active heterosexual Latino men (Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011).

Steps 10 and 11: Pretest and Revise the Intervention

The MuJEReS intervention activities were pretested by female Spanish-speaking members of the Intervention Team with lay community members. Revisions were made to the intervention activities based on this pretesting that garnered extensive feedback.

Results of the Intervention Development Process

The developed MuJEReS intervention provides a comprehensive five Module training for Comadres. The modules, abbreviated activities, theories used, and projected outcomes are presented in Table 2. In module 1, Comadres are introduced to the intervention; the impact of HIV on Latino communities in Latin America, the United States, and finally North Carolina; how the concepts, roles, and strengths of LHAs align with Latino cultural values (e.g., collectivism and familismo); and effective communication. In module 2, Comadres increase their knowledge of reproduction, reproductive anatomy, HIV, and STDs. In module 3, Comadres expand on their growing knowledge of HIV and STD transmission, prevention, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. They explore the influences of machismo and familismo on Latina perspectives, behaviors, and sexual health. They also practice using the APOYO model to develop their communication skills. In module 4, Comadres identify existing barriers that Latinas face in their communities and potential solutions to accessing sexual health services. They continue to improve their communications skills, how to use the APOYO model, and how to effectively serve as a Comadre within their social networks. In module 5, Comadres review information provided and further practice skills taught during their training. This module is implemented at a local health department or free clinic where Latinas can receive comprehensive sexual and reproductive services. At the conclusion of module 5, Comadres receive recognition for their accomplishments during a graduation ceremony signifying initiation of their official roles as Comadres.

Table 2.

Group Training Modules for the MuJEReS Intervention Comadres

| Activity | Theory Applied* | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Module 1: Welcome! Let’s Communicate: Objectives are to (1) create group cohesion and develop group norms, (2) identify roles and strengths of Comadres, (3) increase understanding of the impact of HIV and STDs among Latinos, (4) identify and practice effective communication, and (5) recognize cultural facilitators and challenges to effective communication | ||

| Human knot icebreaker; group introductions; introduction to MuJEReS and impact of HIV and STDs | ↑ Group cohesion and identity; ↑ Knowledge of impact of HIV within Latino community | |

| Brainstorm roles and characteristics of LHAs; discuss collectivism and familismo; develop group norms | TEE | ↑ Group cohesion and identity; ↑ cultural pride through identification of individual and community assets |

| One-way vs. two-way communication game; discussion of communication styles: Aggressive, passive, assertive | SCT and TEE | ↑ Knowledge, self-awareness, and communication self-efficacy |

| Introduction to communication skills; Comadres practice using “I” statements and reflective listening | SCT and TEE | ↑ Communication self-efficacy |

| Reflection on use of communication skills as Comadre: Facilitators, challenges, and potential solutions | TEE | ↓Perceived barriers to effective communication; ↑ Outcome expectations and self-efficacy for Comadre roles |

| Module 2: Knowledge is the First Step: Objectives are to (1) identify function and structure of female and male sexual organs and (2) identify most common STDs, their transmission, symptoms, and treatment | ||

| Introduction to module | ||

| Anatomy: Comadres construct internal/external female and male anatomy; instructor uses plastic models to provide detail and correct misconceptions; Comadres locate organ on life-size picture of internal/external anatomy | SCT and TEE | ↑ Group cohesion and identity; ↑ knowledge of reproductive anatomy; ↑ self-efficacy to communicate about sexual health |

| HIV/STD knowledge: Interactive activity on transmission, symptoms, and treatment of HIV/STDs | TEE | ↑ HIV/STD knowledge |

| Module 3: Protecting Latino Families: Objectives are to (1) identify effective ways to prevent HIV/STDs, (2) identify myths and realities around transmission, prevention, symptoms, and treatment of HIV/STDs, (3) understand how to protect self, family, and community, (4) develop skills to both use and teach the use of condoms, and (5) improve communication skills around negotiating sexual health. | ||

| Icebreaker: “Draw a pig” to stage for discussion of sexual health myths and realities | ||

| Myths and facts about HIV/STDs: Comadres organize myths and facts about HIV/STD prevention, transmission, and symptoms; instructor corrects misconceptions and clarifies knowledge gaps | SCT and TEE | ↑ HIV/STD knowledge |

| Comadres create a list, from which the instructor engages a dialogue around factors that limit protective behaviors (condom use and testing); roles of machismo and familismo are included | SCT and TEE | ↑ Self-efficacy to overcome barriers to condom use and HIV testing; ↑ self-efficacy to reframe health-compromising and bolster health-promoting norms and expectations |

| Negotiating what you want: Comadres problem solve and negotiate (and role play scenarios) using the APOYO model | SCT | ↑ Communication, problem-solving, and negotiation self-efficacy |

| Condom demonstration and practice; Comadres also practice teaching others condom use skills | SCT and TEE | ↑ Self-efficacy with condom skills; ↑ communication self-efficacy |

| Module 4: Working Through Barriers: Objectives are to (1) identify challenges that exist to accessing sexual health services (and possible solutions), (2) improve sexual health information communication skills, (3) learn how to use the APOYO model, and (4) identify appropriate ways to serve as Comadres within existing social networks | ||

| Icebreaker: “React and act” game to set stage for responding to needs of social network | ||

| Brainstorm of barriers that exist that impede Latinas from seeking sexual health resources; Comadres begin to identify possible solutions | TEE | ↑ Self-efficacy in accessing and utilizing sexual health resources; ↑ Problem-solving self-efficacy; ↑ advocacy skills |

| Communicating with others about sexual health: Critical reflection to promote dialogue about being nonjudgmental | SCT and TEE | ↓ Perceived barriers; ↑ outcome expectations and self-efficacy for LHA activities; ↑ comfort communicating with others about sexual health |

| APOYO model: Discussion and role plays | SCT and TEE | ↑ Communication self-efficacy |

| Discovering our way: Brainstorm ways to do their work as LHAs within their social networks | SCT and TEE | ↑ Self-efficacy in accessing and utilizing available sexual health resources; ↑ communication self-efficacy; ↑ advocacy skills |

| Module 5: Bringing It All Together: Objectives are to (1) review essential HIV/STD information, (2) practice condom use skills, (3) identify importance of Comadres to promote community health, and (4) increase familiarity with the local health department to increase comfort with navigating the system; this module includes the graduation ceremony to celebrate of their accomplishments and initiate their roles | ||

| Icebreaker: Comadres assign a characteristic to each letter of a partner’s name | ↑ Group cohesion and identity | |

| Review of basic sexual health information | SCT | ↑ Knowledge |

| Skills practice: How to use a condom, teach others to use a condom, and use the APOYO model | SCT | ↑ Self-efficacy around sexual health and communication skills |

| Resources: Comadres are given a tour to learn about the process of receiving services; resource list of community health centers and clinics is distributed | SCT | ↑ Self-efficacy in accessing and utilizing sexual health resources; ↑ self-efficacy in explaining to other about accessing and utilizing sexual health resources |

| Closure: Synthesis of intervention around communication and sexual health; graduation ceremony | TEE | ↑ Self-efficacy in working with social network members; ↑ confidence in LHA roles |

Abbreviations: APOYO, “poner Atención”-“Preguntar”-“Ofrecer consejo”-“Y”-“Organizar juntos los pasos siguientes”; LHA, lay health advisor; SCT, social cognitive theory; STD, sexually transmitted disease; TEE, theory of empowerment education.

After completing their training, Comadres work with other Latinas within their naturally existing informal social networks (both one-on-one and in small groups), focusing on three main roles of LHAs: (1) Health advisors, (2) opinion leaders, and (3) community advocates. As health advisors, Comadres provide information and resources. For example, a social network member may hesitate to seek HIV testing because she does not speak English, and the local health departments in rural North Carolina have a reputation for having limited interpreters. In this instance, Comadres may describe how to overcome the communication barrier when entering the health department, for example, that eventually an interpreter will be available or staff will work with the woman through limited Spanish to schedule a time when an interpreter is available. In another example, Comadres are trained to teach self-protective skills to others and have penis models and condoms to teach proper condom use skills. As opinion leaders, Comadres reframe health-compromising norms and expectations about being a Latina, particularly around communicating needs and asserting what one wants to both sexual partners and healthcare providers. For example, Comadres are taught how these norms and expectations are reinforced and their own role in changing those that are health compromising and reinforcing those that are health promoting. They learn to reframe the negative and bolster the positive during interactions with social network members, both informally as they experience them and in more formal sessions. Third, Comadres serve as community advocates by bringing the voices of immigrant Latinas to the partnership and to the agencies that offer health services.

Although much of the work that LHAs is often based on their informal provision of social support (Eng, Rhodes, & Parker, 2009; Rhodes et al., 2007; Rhodes, Foley, Zometa, & Bloom, 2007; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Bloom, et al., 2009; Vissman et al., 2009), the Intervention Team developed six 60- to 90- minute group sessions that each Comadre implements with her social network members. The initial meeting establishes each Comadre’s role as an LHA within her social network and legitimizes her role in the presence of Intervention Team members. Other meetings include Comadres teaching Latinas about the correct use of condoms, Comadres leading a discussion to brainstorm and overcome communication barriers with sexual partners (e.g., how to discuss condom use, how to discuss seeking reproductive services), Comadres leading a discussion to brainstorm and overcome communication barriers with providers (e.g., asking questions, bringing up risks and other concerns), Comadres discussing the process of seeking healthcare services (e.g., eligibility, processes) at local facilities (e.g., health departments, free clinics), and Comadres facilitating dialogue for Latinas to explore what it is like being an immigrant Latina in the United States through discussions designed to build positive self-images and further supportive and healthy relationships.

The MuJEReS intervention also includes monthly group meetings for Comadres to discuss implementation successes and challenges, provide social support to one another, plan supplemental activities, share experiences, and resolve problems.

Discussion

Currently there is a dearth of health-promoting interventions designed to meet the needs of immigrant Latinos, and the MuJEReS intervention fills a critical gap in HIV prevention interventions available for Latinas. The intervention is unique because it (1) is designed for immigrant Spanish-speaking Latinas from Mexico and Central America who tend to be recently arrived, have not been exposed to HIV prevention outreach efforts in their countries of origin, and have low levels of acculturation and limited understanding and perceived access to healthcare services; (2) is a community-level intervention based upon community values (collectivism and familialism) and community assets, including natural helpers and existing informal supportive social networks; (3) has the potential to impact large numbers of Latinas through an LHA approach, which is particularly important given the growth rate of the epidemic within the highly vulnerable Latino community; (4) fulfills a need for early intervention before visits to an STD clinic are warranted; and (5) focuses on heterosexual risk as primary mode of transmission.

Furthermore, the LHA approach has the potential to, and the MuJEReS intervention is designed to, build community capacity by training Latinas to help themselves through skills development. Comadres develop leadership, public speaking, and community mobilization skills, which are transferable to other health issues. Given that HIV and STDs are among a multitude of health challenges disproportionately affecting Latinas, interventions that develop capacity are key to addressing the broader set of health disparities experienced by these vulnerable and neglected populations. LHA interventions may be even more key given anti-immigration sentiment in North Carolina and throughout the United States that discourages Latinos from seeking services that they need and for which they are eligible (Rhodes et al., 2007; Vissman et al., 2011). LHAs may be able to build trust and facilitate Latinas within their social networks increasing knowledge, building skills, and changing behavior.

Building on a process similar to that used by the CBPR partnership previously to develop evidence-based interventions (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Bloom, et al., 2009; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Montano, et al., 2006), the CBPR partnership blended the real lived experiences of Latino men and women, sound behavioral theory, and locally collected formative research to develop an intervention that is ready for implementation and evaluation. The intervention also contains elements that effective HIV prevention interventions share, including incorporating locally collected data (as outlined in steps 4 and 5) and tailoring to a defined audience; being gender specific; having a solid theoretical foundation (i.e., social cognitive theory and empowerment education); incorporating discussions of barriers to, and facilitators of, sexual health; exploring gender norms and expectations; increasing self-esteem and group pride; increasing risk reduction norms and social support for protection; building skills to perform technical, personal, or interpersonal skills through role plays and practice; and offering guidance on how to utilize available services (Herbst et al., 2007; Huedo-Medina et al., 2010; Lyles, Crepaz, Herbst, & Kay, 2006; Lyles, et al., 2007; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011).

The process of intervention development has not been well articulated in the literature. Because the blending of perspectives of community members, organizational representatives, and academic researchers through authentic CBPR may yield more informed intervention approaches and content, there is a need for guidance about how to systematically develop promising community-level interventions using CBPR. Our partnership has developed this approach to intervention development that can be applied to other communities and populations, and other health issues by CBPR partnerships and practitioners. Although we used it to develop an intervention for Latinas, we are currently applying these steps to develop an HIV prevention intervention for Latino MSM, again in partnership with community members themselves.

Given the need to meet prevention needs of disproportionately affected communities in the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, this systematic intervention development process offers an approach to intervention development in general, and through CBPR in particular. It has been suggested that the most successful interventions to prevent HIV may need to be based on responding to immediate local community priorities and needs while building capacity for communities to act on their own behalf (Gupta, Parkhurst, Ogden, Aggleton, & Mahal, 2008).

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Grant # R24MD002774 to Dr. Rhodes.

Biographies

Dr. Rhodes is a public health scientist whose research focuses on health promotion and disease prevention among Latinos and other vulnerable populations using authentic approaches to empowerment and community-based participatory research (CBPR).

Ms. Kelley is a MPH candidate with a concentration in Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases, whose research interests include infectious diseases, health disparities and global health.

Ms. Simán, originally from El Salvador, is a Latino community advocate, health educator, and program administrator who is committed to empowerment and community capacity development among Latina women and Latino men.

Ms. Cashman is committed to authentic approaches to public health program development and implementation; she currently coordinates such activities within urban community health centers and works to increase access to healthcare for underserved populations.

Mr. Alonzo, originally from Peru, is a program manager who is committed to meeting the health care needs of immigrants through the careful and informed development, implementation, and evaluation of meaningful interventions designed to meet community priorities and needs.

Dr. McGuire, fluent in Spanish, is a resident in Obstetrics and Gynecology, and a health educator with specific interests in Latina women’s health.

Ms. Wellendorf, a Mexican American originally from Los Angeles, CA, is a community advocate and health educator working with Latina women and adolescents on sexual health issues.

Ms. Hinshaw is a community educator and organizer on behalf of the Latino community.

Dr. Boeving Allen is a clinical psychologist whose research focuses on the psychological adjustment of women, children, and families in the context of chronic illness.

Mr. Downs, originally from Nicaragua, is a health educator who coordinates the Latino Partnership project, a community-level soccer team-based social network intervention to promote sexual health among heterosexual immigrant Latino men in central North Carolina.

Mrs. Brown is a health educator with >10 years, experience working on the development and implementation of innovative sexual health interventions for, and in close partnership with, local communities.

Mr. Martinez, originally from Havana, Cuba, is a law student whose interests include the intersections of immigration policy and immigrant health; he is particularly interested in improving the health and wellbeing of undocumented immigrant Latinos and other disenfranchised communities.

Ms. Duck is the Executive Director of Chatham Social Health Council, community-based organization to meet the sexual health needs of neglected populations in rural North Carolina.

Dr. Reboussin is a biostatistician whose interests include innovative approaches to evaluating risk-related outcomes within large community trials.

References

- Amaro H, Raj A. On the margin: Power and women’s HIV risk reduction strategies. Sex Roles. 2000;42:723–749. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Becker AB, Israel BA, Allen AJ. Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR partnerships. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. pp. 52–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman R, Eng E, Simán F, Rhodes SD. Exploring the sexual health priorities and needs of immigrant Latinas in the southeastern US: A community-based research approach. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23:236–248. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV prevalence estimates–United States, 2006. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 2008a;57:1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (CDC) Subpopulation estimates from the HIV incidence surveillance system–United States, 2006. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 2008b;57:985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (CDC) HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Atlanta: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (CDC) 2011 Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Prevention Interventions. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Rhodes SD, Parker EA. Natural helper models to enhance a community’s health and competence. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. Vol. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. pp. 303–330. (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Education for critical consciousness. New York: Seabury Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Hendriksen ES, Collins EM, Duran RE, Safren SA. Latinos and HIV/AIDS: Examining factors related to disparity and identifying opportunities for psychosocial intervention research. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:582–602. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9402-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurman TA, Becker D. Factors affecting Latina immigrants’ perceptions of maternal health care: findings from a qualitative study. Health Care for Women International. 2008;29:507–526. doi: 10.1080/07399330801949608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Marin BV. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS, Higgins J, Bentley ME, Nathanson CA. The social constructions of sexuality: Marital infidelity and sexually transmitted disease-HIV risk in a Mexican migrant community. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1227–1237. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huedo-Medina TB, Boynton MH, Warren MR, Lacroix JM, Carey MP, Johnson BT. Efficacy of HIV prevention interventions in Latin American and Caribbean nations, 1995–2008: A meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:1237–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasarda JD, Johnson JH. The economic impact of the Hispanic population on the state of North Carolina. Chapel Hill: Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Knipper E, Rhodes SD, Lindstrom K, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Montano J. Condom use among heterosexual immigrant Latino men in the southeastern United States. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:436–447. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.5.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Kay LS. Evidence-based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of the CDC’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(4) Suppl A:21–31. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin BV, Gomez CA, Tschann JM. Condom use among Hispanic men with secondary female sexual partners. Public Health Reports. 1993;108:742–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. 2007 HIV/STD surveillance report. Raleigh: Author; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed December 8, 2008];New estimates profile new HIV infections in North Carolina. 2008b from. http://www.dhhs.state.nc.us.

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Epidemiologic profile for HIV/STD prevention & care planning. Raleigh: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Institute of Medicine. NC Latino health 2003. Durham: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2006 Retrieved March 2007 from. http://www.schs.state.nc.us/SCHS/brfss.

- Organista KC, Carrillo H, Ayala G. HIV prevention With Mexican migrants: Review, critique, and recommendations. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37(Suppl. 4):S227–S239. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141250.08475.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organista KC, Organista PB, Bola JR, Garcia de Alba JE, Castillo Moran MA. Predictors of condom use in Mexican migrant laborers: Exploring AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of female Mexican migrant workers. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:245–265. doi: 10.1023/a:1005191302428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD. Demonstrated effectiveness and potential of CBPR for preventing HIV in Latino populations. In: Organista KC, editor. HIV prevention with Latinos: Theory, research, and practice. (In press). [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Benfield D. Community-based participatory research: An introduction for the clinician researcher. In: Blessing JD, editor. Physician assistant’s guide to research and medical literature. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 2006. pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Eng E, Hergenrather KC, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Montano J, et al. Exploring Latino men’s HIV risk using community-based participatory research. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31:146–158. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Fernandez FM, Leichliter JS, Vissman AT, Duck S, O’Brien MC, et al. Medications for sexual health available from nonmedical sources: A need for increased access to healthcare and education among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern USA. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2011;13:1183–1186. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Foley KL, Zometa CS, Bloom FR. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: A qualitative systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Montaño J. Outcomes from a community-based, participatory lay health advisor HIV/STD prevention intervention for recently arrived immigrant Latino men in rural North Carolina, USA. AIDS Ed Prev. 2009;21(Suppl. 1):104–109. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Griffith D, Yee LJ, Zometa CS, Montaño J, et al. Sexual and alcohol use behaviours of Latino men in the southeastern USA. Culture. Health & Sexuality. 2009;11:17–34. doi: 10.1080/13691050802488405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montano J, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Bloom FR, et al. Using community-based participatory research to develop an intervention to reduce HIV and STD infections among Latino men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18:375–389. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Stowers J, Davis AB, Hannah A, et al. Boys must be men, and men must have sex with women: A qualitative CBPR study to explore sexual risk among African American, Latino, and white gay men and MSM. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2011;5:140–151. doi: 10.1177/1557988310366298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilkin A, Alegria-Ortega J, Montaño J. Preventing HIV infection among young immigrant Latino men: results from focus groups using community-based participatory research. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98:564–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Malow RM, Jolly C. Community-based participatory research: a new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22:173–183. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Vissman AT, DiClemente RJ, Duck S, Hergenrather KC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a culturally congruent intervention to increase condom use and HIV testing among heterosexually active immigrant Latino men. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:1764–1765. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9903-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern State Directors Work Group. Southern States Manifesto: Update 2008. HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the South. Birmingham: Southern AIDS Coalition; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2008 American Community Survey data profile highlights: North Carolina fact sheet. Vol. 2009. Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vissman AT, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Bachmann LH, Montaño J, Topmiller M, et al. Exploring the use of non-medical sources of prescription drugs among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern USA. Journal of Rural Health. 2011;27:159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissman AT, Eng E, Aronson RE, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Montaño J, et al. What do men who serve as lay health advisors really do?: Immigrant Latino men share their experiences as Navegantes to prevent HIV. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21:220–232. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissman AT, Hergenrather KC, Rojas G, Langdon SE, Wilkin AM, Rhodes SD. Applying the theory of planned behavior to explore HAART adherence among HIV-positive immigrant Latinos: Elicitation interview results. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;85:454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrana RE, Cornelius LJ, Boykin SS, Lopez DS. Latinas and HIV/AIDS risk factors: Implications for harm reduction strategies. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1152–1158. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]