Abstract

Insurance coverage for mental health services has historically lagged behind other types of health services. We used a simulation exercise in which groups of laypersons deliberate about healthcare tradeoffs. Groups deciding for their ‘‘community’’ were more likely to select mental health coverage than individuals. Individual prioritization of mental health coverage, however, increased after group discussion. Participants discussed: value, cost and perceived need for mental health coverage, moral hazard and community benefit. A deliberative exercise in priority-setting led a significant proportion of persons to reconsider decisions about coverage for mental health services. Deliberations illustrated public-spiritedness, stigma and significant polarity of views.

Keywords: Mental health, Insurance, Health policy, Consumer preference

Background

Public opinion surveys have documented widespread concern about insurance coverage for mental health services. A national poll conducted for the National Mental Health Alliance (NMHA) revealed that 93 percent of Americans believe mental illnesses should be treated the same as physical illnesses (National Mental Health Association 2008). Support for parity was strong and did not vary by age, income, region or race. A more in depth examination, however, reveals that attitudes about insurance coverage of mental health services may be more complicated.

A review of public opinion on mental health services and the parity debate by Kristina Hanson affirms that many studies cite strong support for mental health and substance abuse (MH/SA) treatment benefits by the public; yet, she warns ‘‘some evidence suggests that this support is relatively soft in that it deteriorates rapidly if the potential for personal financial sacrifice is acknowledged’’ (Hanson 1998). In one survey, ‘‘support for a guaranteed mental health benefit dropped from 69 percent of respondents to 34 percent when the survey questions indicated that higher taxes or premiums would be involved’’ (Institute for Policy Research, 1994). In another telephone survey mental health was chosen by 28% of subjects as the coverage they would be most likely to give up (Los Angeles Times 1994). Such evidence suggests that coverage decisions may be influenced by individuals’ concerns about the best use of their money, or by perceptions of low personal risk and reluctance to help support the care of others. Additionally, certain beliefs or attitudes such as treatments for MH/SA conditions being ineffective or persons with MH/SA conditions being responsible for their symptoms may be associated with lower financial support for mental health services (Corrigan et al. 2004b).

Corporate employers appear to place a greater value on MH/SA services. Although 100% of benefits officers of Fortune 500 companies rated coverage for outpatient treatment for cocaine use as important, only 61% of the public agreed. Public respondents distinguished between types of MH/SA services: 88% of respondents who answered that MH/SA services should ‘‘always’’ be covered would cover treatment of a suicidal patient; 70% would cover treatment for severe depression (Fowler Jr. et al. 1994). Such studies however, do not tell us why there are differences in these priorities. Employers may consider MH/SA treatment important because of the potential overall positive effects on productivity, or because they know more about the general incidence or prevalence rates of mental illness in workers. Indeed, self-insured companies and large employers provide more generous mental health and substance abuse benefits than other employers (Jensen and Morrisey 1991; Merrick et al. 2001).

Public opinion reflecting uncertainty about mental health coverage may also be related to evidence that suggests that the public is not well informed about mental illness, treatment, and coverage, and may harbor misperceptions and stereotypes (Corrigan et al. 2001a; Gyrd-Hansen et al. 2002; Halpert 1969; Link et al. 1999; McSween 2002). In a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation survey, 60% of respondents thought they should know more about mental illness, 87% of respondents identified mass media as their primary source of knowledge, while only 34 percent rated mass media reporting as very or extremely believable (Borinstein 1992). Americans also know little about the debate on expanding MH/SA benefits. When asked if they knew whether mental health coverage was included in congressional Republicans’ legislative proposals in the early 1990s, 31 percent of participants responded that such a benefit was included, 20 percent that it was not, and 49 percent that they did not know the answer to the question (Princeton Survey Research Associates 1993). Hanson reasons that ‘‘the conceptual isolation of MH/SA treatment services from physical health care has resulted in a lack of public interest in the current mechanisms for insuring persons with mental illness’’ (Hanson 1998). A more informed public might respond differently (Bartels 1996). There is a dearth of recent literature regarding public support for mental health coverage. Recent articles illustrate potential service use or financial cost implications around parity implementation (Dixon 2009; Trivedi et al. 2008); however, public engagement in this debate is lacking.

Interest in and familiarity with an issue can often help to foster understanding and decrease misperceptions and stereotypes (Corrigan et al. 2001b; Zuvekas and Meyerhoefer 2009). In contrast, lack of familiarity can lead to stigma and can affect help-seeking and disclosure of MH/SA problems and subsequently lower recognition of the prevalence of MH/SA disorders among the general population. This becomes a phenomenon that, with the low levels of mental health service use relative to need, forms a vicious cycle of public detachment and misunderstanding. From previous research we know that although 26% of the American population will suffer from a mental disorder in a given year, less than half of those individuals will use services (Kessler et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2005).

To be valuable and credible, public input on policy options must be informed and reflective. Although survey data can help us to quantify the range and rates of public opinions it is often not clear what lies behind those responses or how fixed or malleable opinions are. In this study, we used a simulation exercise in which groups of laypersons deliberate about healthcare tradeoffs, to provide insight into public values and preferences for MH/SA services. General feasibility of the CHAT exercise to facilitate collective decision-making, stimulate dialogue about healthcare choices, elicit individual preferences and incorporate responses of others within a group has been demonstrated by other studies (Danis et al. 2002; Danis et al. 2004; Goold et al. 2005). This study applies this unique approach for eliciting attitudes in order to understand public values regarding MH/SA insurance coverage and how deliberation and sharing of MH/SA related experiences can influence subsequent choices for, prioritization of and attitudes about MH/SA insurance coverage relative to other types of coverage. We also examined: (1) changes in decisions to include MH/SA coverage in a health insurance plan before and after group deliberations and (2) differences in choice of and attitudes toward MH/SA coverage within a group versus individual context.

Methods

Study Population and Sampling

Five hundred sixty-two individuals took part in 50 group discussions of limited resources, using the CHAT© (Choosing Healthplans All Together) exercise. All fifty exercises were professionally facilitated and overseen by Praxis, Inc (a consulting firm specializing in the evaluation of educational and human service programs. Praxis Inc was hired to help with recruitment and facilitation of the focus groups) in 1999–2000. Twenty-five group sessions (N = 255) were audiotaped and transcribed. Consequently, although quantitative data is available for all groups, qualitative data is only available for half of the group discussions.

The sample included North Carolina residents without healthcare expertise, recruited from ambulatory care and community settings. Participants were not told that the study would discuss mental health specifically, but were informed that the study referred to healthcare coverage more generally. We chose to oversample low-income individuals. Although this may decrease the study’s statistical ‘generalizability’ it was also considered a strength given that these groups tend to be underrepresented in other surveys. Typical sites for recruiting participants included doctors’ offices, senior citizens’ centers, and community centers. Participants were recruited in person by an employee of Praxis, Inc. or responded to written flyers or materials about the project. Volunteers received $25 to $75 cash to compensate them for their participation. Groups were assembled and convened to be homogeneous with regard to two characteristics: type of health insurance (1 Medicaid, 7 Medicare or Medicare/Medicaid, 9 private, 8 uninsured) and site of recruitment (13 general groups and 12 healthcare groups). Otherwise groups were recruited to be, as much as possible, heterogeneous with respect to other characteristics (gender, age, race). Therefore, although we felt it was essential to include a range of views in this research, the primary goal of this study was not to compare views by these characteristics.

Of the 25 groups, 13 were recruited from community settings and 12 were recruited from healthcare settings. There were eight groups of uninsured individuals and 17 groups of insured individuals. Insured groups were composed either of senior citizens covered by Medicare, or younger individuals who were insured either through Medicaid or with private (commercial) insurance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Group characteristics of participants in the qualitative study (N = 255)

| Recruitment site | Community | Healthcare |

|---|---|---|

| Uninsured | 4 | 4 |

| Insured | 9 | 8 |

| Medicare* | 5 | 2 |

| Medicaid | 0 | 1 |

| Commercial | 4 | 5 |

| Total | 13 | 12 |

Includes groups of individuals eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid

Instruments

This study relied on Choosing Healthplans All Together (CHAT), a structured, small group simulation exercise. CHAT allows groups of nine to fifteen laypersons to construct health plans constrained by limited resources. The CHAT exercise is designed to provide a fair opportunity to all participants to voice priorities or considerations based on their experiences. CHAT has been validated and used in projects in several states in the US and abroad with a variety of participants, and has been rated highly by participants regarding ease of use, information sharing and enjoyment (Danis et al. 2002; Danis et al. 2004; Goold et al. 2004). (Further details about the CHAT exercise can be obtained from the authors). Group sessions were led by trained facilitators and lasted approximately 2.5 h.

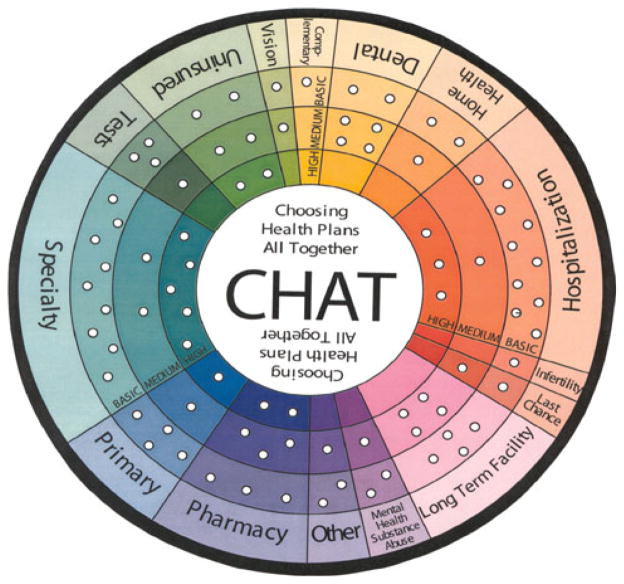

The first step of CHAT uses a game board resembling a pie chart (Fig. 1) in which 15 insurance benefit categories are represented. Participants receive 50 pegs which represents 100% of the premium cost. This allows them to fill only about 60 percent of the holes on the CHAT board, forcing them to ‘‘simultaneously weigh desired clinical services against the realities of resource constraints’’ (Goold et al. 2005) when choosing their health insurance package. Participants may select varying levels of coverage (see Table 2 for coverage descriptions) for each benefit category (basic, medium or high) or may forgo a category altogether. The benefit choices vary somewhat for senior and working-age participant groups. Specifically, the MH/SA benefit option for seniors includes the choice of only one level of coverage (the Basic level) while the benefit option for the working-age participants includes a choice between basic and medium levels. The senior CHAT version also does not include the infertility category and differs in costs compared to the version of CHAT used with participants of working-age (eg., relative costs for home health care and longterm care were higher for seniors). Although participants may have conflicting views about coverage of varying conditions (eg., between treatment for mental health versus substance abuse disorders) the structure of the benefits reflects those that may be offered in a typical insurance plan.

Fig. 1.

The CHAT board is shown with the number of pegs for each service type and coverage level visible as holes around the board. Each peg represents 2% of the per member per month (PMPM) cost of coverage

Table 2.

Details of benefits

| Type of coverage

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Basic | Medium (not available for Senior groups) | |

| Mental Health and Substance Abuse (pays for counseling and therapy, treatment of mental illness, and alcohol and drug abuse) | 2 pegs: Your plan pays for up to 30 visits per year to a therapist. You pay $10 per visit. Your plan pays for up to 30 days per year in a hospital for mental illness or drug abuse. You pay $50 for each day in the hospital. | 2 + 1 pegs: Your plan pays for an unlimited number of visits to a therapist or counselor. You pay nothing per visit. Your visits are free. You plan pays for an unlimited number of days in a hospital for mental illness or drug abuse. You pay nothing for each day in the hospital. |

After making benefit selections, participants spin a roulette wheel (including all service categories arrayed around the circumference as shown in Fig. 1) and receive a hypothetical ‘‘health event’’ corresponding to the category on which they land. Each health event describes an illness scenario and the associated consequences of coverage choices, including out-of-pocket payment responsibilities, access and choice of provider or treatment. For example, in one of the MH/SA category health events, a player is advised that his/her spouse has become very depressed, and recently began talking about feeling suicidal. Players are instructed to read the event aloud to the group and are then encouraged to reflect aloud on their benefit coverage choices in light of their health event.

These two steps comprise Round 1. All together there are four rounds, allowing participants to make choices and face consequences (1) alone, choosing benefits for themselves and their families, (2) in groups of three, choosing benefits for their neighborhood, (3) as an entire group, choosing benefits for the community and (4) once again, choosing for themselves. Each participant receives a ‘‘health event’’ after both Round 1 and Round 2. This progression promotes group decision-making and allows comparison of individual and group choices.

Data Collection

Group discussions were audio recorded and participants were given an alias to preserve anonymity. Participants completed both a pre-exercise questionnaire to collect socio-demographic and health information and a post-exercise questionnaire which asked participants about their views on the CHAT exercise (Gallup Organization 1994).

This project was deemed exempt from continuing IRB review by the Offices of Human Subjects Research at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health, and approved by IRBs at the University of Michigan, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Duke University.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics (Table 3) characterize study participants and their attitudes towards health insurance coverage. McNemar’s chi-square test was employed to assess the degree of agreement between individual health care coverage choices made during the first and fourth cycles of the game. To use McNemar’s test, coverage choice was recoded into a dichotomous indicator (i.e., coverage was either selected or not selected).

Table 3.

Participant characteristics and baseline attitudes (N = 562)

| Entire Sample (N = 562 in 50 groups)

|

Recorded Subset (N = 255 in 25 groups)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | %* or Mean ± SD | N | %* or Mean ± SD |

| Age (in years) | – | 47.8 ± 19.0 | – | 47.1 ± 19.4 |

| Female | 290 | 52.5 | 137 | 53.7 |

| Missing | 10 | – | ||

| Race (missing 47/562) | ||||

| White | 312 | 56.2 | 150 | 58.8 |

| Black or African American | 219 | 39.5 | 91 | 35.7 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 12 | 2.3 | 4 | 1.6 |

| Other/Unknown | 24 | 4.4 | 10 | 3.9 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Private Insurance | 172 | 44.3 | 89 | 38.9 |

| Medicaid | 15 | 3.9 | 7 | 3.0 |

| Medicare | 90 | 23.2 | 81 | 35.2 |

| Other Insurance | 25 | 6.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Uninsured | 86 | 22.2 | 53 | 23.0 |

| Missing | 174 | – | 25 | – |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 145 | 26.1 | 58 | 23.2 |

| Single or never married | 212 | 38.1 | 94 | 37.6 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 199 | 35.8 | 98 | 39.2 |

| Educational Attainment | ||||

| Less than high school | 61 | 10.9 | 22 | 8.7 |

| High school graduate or GED | 144 | 25.8 | 70 | 27.6 |

| Some college | 137 | 24.6 | 67 | 26.4 |

| College graduate or more | 216 | 38.7 | 95 | 37.4 |

| Household Income | ||||

| $0 – \ $7,500 | 130 | 25.0 | 36 | 14.1 |

| $7,500 – \ $15,000 | 106 | 20.3 | 54 | 21.1 |

| $15,000 – \ $35,000 | 140 | 26.9 | 70 | 27.4 |

| $35,000 or more | 145 | 27.8 | 60 | 23.5 |

| Unknown or not reported | 41 | – | 35 | 13.7 |

| Health Status | ||||

| Excellent | 108 | 19.3 | 53 | 20.9 |

| Very Good | 192 | 34.3 | 91 | 35.8 |

| Good | 169 | 30.2 | 79 | 31.1 |

| Fair | 81 | 14.5 | 29 | 11.4 |

| Poor | 10 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.8 |

| Chronic illness in household in past year | 193 | 36.0 | 82 | 34.3 |

| Member of household hospitalized in past 6 months | 96 | 17.6 | 36 | 14.6 |

| ≥ 1 physician visits in households in past 6 months | 531 | 94.5 | 235 | 92.2 |

| Out-of-pocket healthcare costs, past 12 months | ||||

| $0 | 88 | 18.2 | 29 | 11.4 |

| < $500 | 196 | 40.5 | 96 | 37.6 |

| $500 – < $2,000 | 137 | 28.3 | 66 | 25.9 |

| $2,000 or more | 63 | 13.0 | 19 | 7.4 |

| Unknown | 78 | – | 45 | 17.6 |

Percentages do not always add to 100 due to unknowns and rounding. The number of individuals with unknown values ranges from 2 to 5; where more frequent, we report the number of unknowns as a separate category

In order to better understand why benefit choices were selected, we analyzed the transcripts from twenty-five audio taped groups (n = 255 participants). Each group transcript was searched, both manually and using N6 (QSR software), for terms related to MH/SA. Search terms included depression, substance abuse, alcohol, addict, psych, mental health and schizophrenia. As text was identified, new search terms were added. Investigators read all text preceding and following the search terms and determined when to code dialogue as relating to mental health/illness, substance abuse, or related conditions. One investigator (SEL) read all text coded for MH/SA in an open coding process, developing a list of reasons, justifications and values that were expressed when participants chose whether and to what extent to include MH/SA benefits. This coding scheme was then compared to a more comprehensive coding scheme that had been developed previously for all dialogue (i.e., not just MH/SA) by other investigators (SDG, NMB). Without exception, all codes identified during interpretation of MH/SA discourse mapped directly on themes in the larger, main coding scheme. In addition to line by line coding using this comprehensive coding scheme, two investigators (SEL, NMB) read and analyzed all MH/SA dialogue for overarching general themes, hypothesis generation and patterns and relationships among themes. Although a coding framework had already been developed to analyze dialogue referring to all healthcare categories, open coding was performed again specifically for the text referring to MH/SA discourse to ensure saturation of the coding structure and reliability of coding.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participants had a mean age of 48 and a wide range of incomes and educational attainment (Table 3). Low income persons were over-represented. About half of participants were men and 44% self-identified as non-white race. More than one quarter reported fair or poor health status. A similar percentage reported a chronic or serious illness in their household and about one-fifth reported a household member hospitalized in the past 6 months. The vast majority had had a visit with a doctor in the past year. The overall sample was older and more ethnically/racially diverse than the average North Carolina resident (compared with Census data from 2000).

Selection of Insurance Coverage

Individuals’ prioritization of mental health coverage increased after group discussions. Just over one third (36.7%) of participants in senior groups included mental health coverage before the exercise while 45% selected it following group discussion (Table 4). These percentages were higher for working-age groups: 60.8% chose some mental health coverage prior to and 69.6% after group discussion; increases were statistically significant (McNemar’s Chi = 11.57, P = 0.0007). The same trend occurred in subgroup analyses of Medicaid, uninsured, and insured participants. Not surprisingly, individuals who agreed prior to the group exercise that MH/SA coverage was important were more likely to select MH/SA coverage (66.5 vs. 55.2%, P = 0.01). Neither income nor education was associated with an individual’s choice of mental health coverage.

Table 4.

Initial and final individual choices for mental health and substance abuse coverage

| Population | Initial individual N (%) | Final individual N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working-age (n = 441) | None | 155 (39.3) | None | 119 (30.2) |

| Basic | 113 (28.7) | Basic | 159 (40.4) | |

| Medium | 126 (32.0) | Medium | 116 (29.4) | |

| Senior (n = 121) | None | 75 (62.5) | None | 66 (55.0) |

| Basic | 44 (36.7) | Basic | 54 (45.0) | |

| Medium | Not available | Medium | Not available | |

Working-age groups comprised publicly and privately insured and uninsured adults between 18 and 65. Senior groups included mostly adults ≥ 65 years old, although a few participants in these groups were under 65. Senior group participants’ choices are analyzed and presented separately since the options available in CHAT and their relative costs differed from those available for the other groups. Missing data for Working-age groups represented about 10%; for Senior groups < 1%

McNemar’s Chi-square = 11.57, P = 0.0007, for comparison of proportion choosing No Coverage

Groups selected MH/SA coverage more frequently than individuals (Table 5). Nearly all groups, including 9 of 10 senior groups and 38 of 39 working-age groups (including 21 of 22 uninsured groups) included MH/SA coverage in their final group selections.

Table 5.

Group benefit choices for MH/SA

| Working-age group choices

|

Senior group choices

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MH/SA Benefit | Frequency (%) | MH/SA Benefit | Frequency (%) |

| (n = 39) | (n = 10) | ||

| No benefit | 1(2.6) | No benefit | 1(10) |

| Basic benefit | 28(71.8) | Basic benefit | 9(90) |

| Medium benefit | 10(25.6) | ||

Group dialogue about MH/SA coverage reflected a variety of themes which we organized into the following major categories: magnitude of value in MH/SA coverage, beliefs and attitudes about treatment efficacy, benefit to the community or society as a whole, value of MH/SA coverage relative to other options, the high cost of care (if not insured), low personal risk of MH/SA problems, and moral hazard. Finally we identified ‘‘polarity in beliefs’’ as an overarching theme evident throughout many parts of the dialogue.

Magnitude of Value in MH/SA Coverage

The theme ‘‘magnitude of value in MH/SA coverage’’ referenced dialogue about the potential for MH/SA coverage to protect against substantial harms or losses, or when MH/SA coverage was described as important or necessary or, conversely, as trivial or unnecessary.

‘‘And I think mental health, substance abuse for one more. The benefits you get from that are very important.’’

Harms or losses which participants suggested might be avoided through insurance coverage and subsequent access to treatment included foregone social or work activities to both individuals with mental illness and family members or caregivers.

‘‘I think we should have at least a basic level of mental health and drug abuse because that’s a big reason people miss work.’’

‘‘Well most of the homeless people they do have a mental illness or a drug abuse problem. This is true and of course a lot of people get into drug abuse because they do have a mental illness and it’s because I realize that in this room 1 out of every 4 of us are going to be affected by mental illness by a family member or ourselves. 22–25% of people have neurosis and the others that can not hold down a job socially.’’

Participants reflected on the prevalence of MH/SA problems, and commented on the importance of coverage for those in the community as well as individuals, families and workplaces.

‘‘Mr. J. says we have a lot of people in [city] that need to go to mental health for substance abuse.’’ ‘‘I think the major thing is depression. And that has such a high incidence. Depression is also very common. The triggers for depression can be losses or chronic illnesses and those are things that almost any person of the senior age will encounter.’’

Participants recognized that MH/SA services are essential and yet often undercovered.

‘‘I know a lot of insurance companies don’t cover mental health … even if you have insurance through your company, … and, it’s, I mean, definitely a need… It helps thousands and thousands.’’

Beliefs and Attitudes About Treatment Efficacy

Beliefs or attitudes about treatment efficacy also influenced coverage choice. Although many believed coverage for MH/SA treatment was generally important, participants expressed great uncertainty regarding medical treatment and services available to help persons with MH/SA problems.

Some felt treatment might be potentially harmful:

‘‘Because most of time they put you on all this BS medication that screws you up worse than what you were when you got there.’’

‘‘I mean, I’ve had a personal experience with a friend who had anorexia and she went to a ‘‘wham, bam, thank you ma’am’’ clinic and they didn’t do anything! She was sicker!’’

Others expressed the view that the use of medical treatments for MH/SA conditions was inappropriate:

‘‘I just, I feel like there’s a deeper seated problem than there is mental health being needed to be treated. They’re not treating the origin of the problem.’’

Other participants suggested some problems are actually facilitated through the provision of MH/SA problems.

‘‘I’m referring, to the way the psychiatrist told me right now is that a high percentage of women in our society are diagnosed as depressed and, of course, that means medication. I believe that their problems do not need to be dealt with that way and it just becomes a habit…Maybe we can reverse the problem by not having insurance coverage knowing that they’re gonna get paid for it.’’

Finally, some comments reflected judgments that some MH/SA services could be provided by other sources or managed in other ways.

‘‘The mental health stuff doesn’t appeal to me. If you have to do that, I would say family might be able to handle some of it. I would suggest not doing that.’’

Benefit to the Community or Society as a Whole

Support for MH/SA benefits was sometimes justified as a benefit to the community or society as a whole, for instance, by keeping persons with MH/SA problems from posing a danger to others. This was especially evident in dialogue about the seriousness of addiction as a problem in communities.

‘‘I made a suggestion about certainly including pharmaceuticals and mental health. That doesn’t only benefit the patient, it benefits the community. We might not have so many problems with psychiatric patients not being under care.’’

When discussing need for basic mental health coverage for the community, one respondent stated:

‘‘It actually applies to a reasonable amount of the population; I mean it’s kind of scary when you think about it! There’s supposed to be a lot of drug users around here.’’

Value of MH/SA Coverage Relative to Other Options

Despite the prominent place of dialogue about the importance of MH/SA treatment, and the large magnitude of harm or loss such services aim to prevent, another prominent theme in the dialogue was, paradoxically, the relative unimportance of MH/SA coverage. This sentiment was shared when participants characterized MH/SA services as being a lower priority than other health services.

‘‘If we’re going to have all mental health-well, I have four kids—we need dental.’’

Cost of Care

Another argument proffered about MH/SA coverage appealed to the need to ameliorate the high costs of drug treatments and psychotherapy. This theme was termed cost of care.

‘‘I think we ought to at least have basic mental health. That’s actually an expensive thing.’’

‘‘I’ve been to counseling and if I had to pay for it, it is $95 an hour (if) you’re lucky. I just know it is expensive.’’

Low Personal Risk of MH/SA Problems

While groups discussed the importance of having good mental health care coverage, they often perceived a low personal risk of MH/SA problems, as in the following example:

‘‘That’s, see, for me that’s not a priority because I just don’t see anything like that happening to me.’’

Moral Hazard

Participants discussed both positive and negative aspects of the influence of coverage for MH/SA services on utilization, that is, the economic phenomenon of moral hazard. When coverage is available, they argued, more people will use it, or individuals will use more services than they would if they did not have coverage. On one hand, it was suggested that such availability means more people will use MH/SA services and coverage could decrease the stigma associated with treatment for MH/SA problems and perhaps meet heretofore unmet needs. On the other hand, it was suggested that wide availability of MH/SA services could encourage an inappropriate overuse of services and have a negative impact on health care costs:

‘‘you don’t just go dilly dallying in [to treatment]…for every excuse,… again let’s think of those because [other] people can really abuse the system, I’m afraid.’’

Polarity in Beliefs

Interpretation of group dialogue about MH/SA coverage revealed a strong overarching theme we labeled ‘‘polarity in beliefs.’’ Perceptions of the risk of mental illness provide a telling example. While participants agreed that MH/SA problems are serious and relatively prevalent, participants did not feel personally at risk. The quote below highlights the individual’s understanding for the potential importance of mental health coverage, yet also states that he feels no personal risk or subsequent need for individual MH/SA coverage.

‘‘When I landed on the [red] wheel and ended up with the mental health, it didn’t have any importance – I know it had a lot of importance to a lot of people, I would probably say I prefer not to have it, but again, it can happen to be [valuable].’’

Support for coverage of substance abuse services reflected similar contrasts. Some felt that the gravity of the problem demanded some action (usually for the overall good of the community) while others felt those with substance abuse problems may not be deserving of treatment. There was disagreement as to whether coverage should be provided because a substance abuse problem was considered by some to be a behavioral problem rather than a medical condition.

‘‘Mental health and medical health are totally different… I guess part of my disagreement with it is I’m okay with mental health in the sense of manic depression. I have problems with drug abuse and alcohol abuse. To me, that is a behavior issue more than a mental health issue.’’

Finally, others felt generally conflicted about coverage for MH/SA as they suggested that it is more complicated to ensure coverage for the range of issues categorized as MH/ SA problems compared to other types of medical coverage which is more straightforward.

‘‘It’s not black and white as if you need an organ transplant. There are some issues here that seem to be part of our culture and our society….’’

Discussion

The majority of individual participants, and nearly all groups, chose to include MH/SA benefits in a health benefit package. Consistent with these choices, there was a strong belief that mental health is a significant social issue despite the relatively poor coverage of MH/SA in most existing health insurance relative to other health needs. However, participants’ attitudes about MH/SA treatment were not consistently favorable and polarity in beliefs was evident. While some comments reflected judgments about the importance of MH/SA services for both patients and the community, other comments alluded to MH/SA services as ineffective, unnecessary, and/or able to be ‘‘handled’’ by oneself or one’s family. The polarization of attitudes toward MH/SA care is echoed in public opinion surveys (DYG Inc 1989; Gallup Organization 1994; Hanson 1998), where initial support for mental health parity, for instance, weakens once cost is mentioned.

Comments reflected the stigmatization of those with MH/SA disorders, for instance the need to treat mental illness to assure community safety, and, tellingly, in participants’ unwillingness to confront the possibility of mental illness for themselves. Participants also wondered aloud about the ‘‘medical’’ nature of mental illness, and especially substance abuse. Behavioral matters or problems of character, according to these participants, should not be treated so much as corrected or controlled in other, nonmedical ways. As a result, limited resources were seen as being more deserved elsewhere. Other research has also shown that persons with mental illness are perceived as being more responsible for their situation than persons with physical illness. A study by Weiner et al., showed that persons with mental or behavioral conditions elicited attitudes of little pity, anger, and potential neglect while persons with physical illness elicited pity, no anger, and judgments to help (Weiner et al. 1988). In addition to participants being influenced by stigmatizing attitudes about the origin of MH/ SA conditions in our study, public skepticism regarding the need for treatment for mental illnesses also discouraged participants from choosing MH/SA coverage. These perceptions may have significant associations with policy; Corrigan et al. demonstrated the impact of negative attitudes toward mental illness and treatment efficacy on policy decisions. Their study showed a positive association between perceived importance of mandated treatment and stigmatizing attitudes in participants completing various measures of resource allocation. Allocating resources to mandated treatment (vs. rehabilitation services) was positively associated with attitudes of pity and fear while donation of money to a mental health charity was negatively associated with attitudes of blame or not being willing to help (Corrigan et al. 2004b). Corrigan and Watson have also emphasized the impact of perceptions of personal responsibility in making resource allocation decisions, which our participants reflected in their calls to ‘‘handle it [mental illness]’’ (Corrigan and Watson 2003).

The CHAT exercise and the group deliberations it stimulated affected individuals’ points of view and subsequent decisions; most allocations to MH/SA coverage (even when choosing a plan for themselves and their families) increased after the session. Throughout the CHAT exercise, participant discussion focused on perceived personal risk of mental illness (which most considered low), the trivial, less serious nature of mental illness compared to physical illnesses, mental illness as being something you could or should ‘deal with’ yourself (especially in relation to substance abuse) and about the ineffectiveness of treatment. They also, however, articulated reasons in support of MHSA coverage, including the seriousness of mental illness and addiction, the impact of those diseases on individuals, families, workplaces and communities, and the high cost of obtaining care absent insurance coverage. At least some participants also recognized, in comments after hypothetical health events, and responses to the experiences of other group members, that mental illness might be more of a possibility for themselves or their family members than they initially thought. For example, one participant, after reading a health event in which her spouse was diagnosed with manic-depressive disorder, and hospitalized for 2 weeks, said ‘‘I had no coverage. I would though if I’d known I was going to have problems.’’ Group discussion of the exposure to financial risk that such illness brings might also allow participants with experience to ‘‘win over’’ other participants without such experience. Increased support for MH/SA coverage might also reflect improved understanding about the group nature of insurance and a recognition of the importance of MH/SA services for others. Coverage chosen for one’s self or one’s family is also coverage available to a group or community, and the CHAT exercise, like real allocation decisions, must reflect the tension of tradeoffs between competing needs of many individuals.

These data have implications for many areas of health insurance policy. The past decade has seen improvements in access to and coverage of MH/SA services occurring alongside the expansion of SCHIP, Medicare part D and passage of the Medicare Improvement for Patients and Providers Act (HR 6331). Increases in the treated prevalence of mental disorders among children has been attributed to improvements in access to primary care among children (Glied and Frank 2009). The Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009, signed by President Obama in February 2009, requires dental coverage and mental health parity. The mental health parity act of 2008 improves on the mental health parity act of 1996 by prohibiting financial requirements or treatment limitations which have been more restrictive for MH/SA compared to physical health services (Ostrow and Mand-erscheid 2009). The Medicare Improvement Act specifically mandates a gradual decrease in the copay for mental health services from 50% to align with the copay for physical health services (20%) by 2014 (Shern et al. 2009). Finally, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), passed in March 2010 mandates that qualifying health insurance plans must adhere to enacted legislation requiring mental health and substance abuse parity. Although it is anticipated that the new reform will improve access, leading to 1.15 million new users of mental health services and that there will be increases in mental health related service use (Garfield et al. 2011); of question is the effectiveness of the policy to address the specific needs of those with severe mental illness, how formularies or utilization management will be applied (Garfield et al. 2010) and how this will vary by state (Aggarwal et al. 2010). Additionally, of concern for the future is how MH/SA benefits will vary among private insurance companies as well as public plans, and whether employers will greatly restrict or even eliminate MH/SA coverage in an effort to stem the rising cost of health insurance benefits. So-called ‘‘consumer directed health plans,’’ to the extent they truly permit individuals to select the coverage they think they will need, would, predictably, exacerbate uninsurance for mental illness as consumers underestimate their need for MH/SA services. The data from this study suggest that consumers may substantially underestimate their risk and potential need for MH/SA coverage. As further negotiations are made at the state level it would seem prudent to incorporate deliberative simulation exercises such as CHAT to improve the awareness of both the need and benefits of MH/SA coverage. Such deliberative discussions could facilitate consideration of the prevalence of MH/SA conditions and effectiveness of treatment among consumers and policy-makers. The CHAT model could help demonstrate the relative value of these services among a complicated array of options. If the new legislation is effective in improving access to adequate MH/SA treatments, this could help to reduce stigma especially, if treatments address associated psychotic symptoms or substance abuse which are features associated with high levels of public stigma. (Hinshaw and Stier 2008). Additionally, reducing structural discrimination (i.e., allocating fewer resources or restricting benefits to people with MH/SA problems) may improve public perceptions about the effectiveness of mental health treatments or decrease self-stigma among consumers (Corrigan et al. 2004a) could also be reduced.

Additional implications of this work include incorporation of the CHAT exercise into the process of selecting employer sponsored health insurance plans. For the Capital CHAT project, employees or associates from 41 public and private sector employers sponsored 72 CHAT sessions. Following the study, one of the participating employers used the collected information to modify its benefit plan and a second went on to conduct additional, customized CHAT exercises to seek employee input for possible benefit changes (Danis et al. 2007). Other CHAT papers (Goold et al. 2005) have noted that CHAT might be used as an empowerment tool for consumers and communities and noted recommendations of how citizen participation in health care priority setting might be achieved (Daniels and Sabin 1998; Fleck 1992; Giacomini et al. 2000; Goold et al. 2005; Gutmann and Thompson 2011).

Limitations

While this study contributes new and important information on how members of the general public view and value mental health coverage, the sample is geographically limited and the sample was not designed to achieve statistical proportionality. On the other hand, greater inclusion of the viewpoints of minorities and lower income individuals can be perceived as a strength, since they tend to be under-represented in other studies (including public opinion surveys). Missing data on insurance coverage is also a limitation. Due to a clerical error, half of the groups did not receive the insurance question on their questionnaire. Rather than assume that group type perfectly correlated with insurance type, we treated that item as missing for those participants. As these data were collected in 1999–2000, today’s political environment, and the continuing rise of health care costs may have influenced the public’s view. Mental health coverage, however, has not been a major part of recent discussions about healthcare and therefore new data are lacking. Recent analyses of the General Social Survey by Pescosolido et al. compared attitudes about the causes of mental illness, endorsement for medical treatment and social distance from 1996 to 2006. It suggests increasing public endorsement of a neurobiological model of mental illness and medical treatment; but, this was also associated with increases in stigma and/or social distance (Pescosolido et al. 2010), as has been shown in other studies (Corrigan and Watson 2004; Rusch et al. 2010). This suggests that although there might be increasing support for MH/SA services for the community, the increase in social distance may also be associated with less perceived personal risk for need of MH/SA coverage. Additionally, the CHAT exercise is a simulation exercise and choices made in the exercise may not precisely reflect how individuals would make trade-off decisions in real life. Our study offers new insight into the views of the public and helps to further develop the debate on mental health parity, both through our findings and unique methods.

Conclusions

As public and private institutions struggle to set health care priorities, it is imperative that we gain insight into the values and perspectives of those affected by allocation decisions, and that we assure that the perspectives of diverse individuals and communities are included (Rosenheck 1999). Because individual reasoning may change based on new information or perceptions (Booske et al. 1999; Mechanic 1996), engaging individuals in deliberative activities, wherein they have an opportunity to learn, reflect, and reason collectively, provides an opportunity for public input into policy making that may be an improvement over, or at least complementary to, public opinion polls. Our study suggests that deliberative processes have the potential to broaden individual perspectives, as shown by the increase in individual preferences for mental health coverage from Round 1 to Round 4.

Deliberative forums can help policy makers, grappling with the enduring challenge of limited resources available to meet physical and mental health needs, understand citizens’ reasoning. Insights gained from this and future studies of public deliberations may shed light on an issue that is politically, intellectually and morally complex and, by using a fair, open and transparent process, contribute to an equitable distribution of limited health care resources.

Contributor Information

Sara E. Evans-Lacko, Email: Sara.Evans-Lacko@iop.kcl.ac.uk, Health Service and Population Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, De Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, UK

Nancy Baum, Department of Health Management and Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Marion Danis, Section on Ethics and Health Policy, Department of Clinical Bioethics, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, Bioethics Consultation Service, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Andrea Biddle, Health Policy and Administration, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Susan Goold, Department of Health Management and Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical school, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, Bioethics Program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

References

- Aggarwal NK, Rowe M, Sernyak MA. Is health care a right or a commodity? Implementing mental health reform in a recession. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:1144–1145. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels L. Uninformed votes: Information effects in presidential elections. American Journal of Political Science. 1996;40:194–230. [Google Scholar]

- Booske BC, Sainfort F, Hundt AS. Eliciting consumer preferences for health plans. Health Services Research. 1999;34:839–854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borinstein AB. Public attitudes toward persons with mental illness. Health Affairs. 1992;11:186–196. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.11.3.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Green A, Diwan SL, Penn DL. Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001a;27:219–225. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Green A, Lundin R, Kubiak MA, Penn DL. Familiarity with and social distance from people who have serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001b;52:953–958. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC. Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004a;30:481–491. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Factors that explain how policy makers distribute resources to mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:501–507. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. At issue: Stop the stigma: Call mental illness a brain disease. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30:477–479. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Warpinski AC, Gracia G. Stigmatizing attitudes about mental illness and allocation of resources to mental health services. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004b;40:297–307. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000035226.19939.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels N, Sabin J. The ethics of accountability in managed care reform. Health Affairs (Millwood) 1998;17:50–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.5.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M, Biddle AK, Dorr GS. Insurance benefit preferences of the low-income uninsured. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:125–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M, Biddle AK, Goold SD. Enrollees choose priorities for medicare. Gerontologist. 2004;44:58–67. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M, Goold SD, Parise C, Ginsburg M. Enhancing employee capacity to prioritize health insurance benefits. Health Expect. 2007;10:236–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon K. Implementing mental health parity: The challenge for health plans. Health Affairs. 2009;28:663–665. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DYG Inc. National telephone survey of 1,346 adults conducted for the Robert Wood Johnson Program on Chronic Mental Illness. 1989. Dec 1–11, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck LM. Just health care rationing: A democratic decisionmaking approach. University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 1992;140:1597–1636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler FJ, Jr, Berwick DM, Roman A, Massagli MP. Measuring public priorities for insurable health care. Medical Care. 1994;32:625–639. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199406000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Organization. National telephone survey of 1,001 adults conducted for Cable News Network and USA Today. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RL, Lave JR, Donohue JM. Health reform and the scope of benefits for mental health and substance use disorder services. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:1081–1086. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RL, Zuvekas SH, Lave JR, Donohue JM. The impact of national health care reform on adults with severe mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060792. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini MK, Cook DJ, Streiner DL, Anand SS. Using practice guidelines to allocate medical technologies. An ethics framework. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2000;16:987–1002. doi: 10.1017/s026646230010306x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glied SA, Frank RG. Better but not best: Recent trends in the well-being of the mentally ill. Health Affairs. 2009;28:637–648. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goold SD, Biddle AK, Klipp G, Hall CN, Danis M. Choosing healthplans all together: A deliberative exercise for allocating limited health care resources. Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law. 2005;30:563–601. doi: 10.1215/03616878-30-4-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goold SD, Green SA, Biddle AK, Benavides E, Danis M. Will insured citizens give up benefit coverage to include the uninsured? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:868–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.32102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann A, Thompson D. Deliberating about bioethics. The Hastings Center Report. 2011;27:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyrd-Hansen D, Kristiansen IS, Nexoe J, Nielsen JB. Effects of baseline risk information on social and individual choices. Medicine Decision Making. 2002;22:71–75. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0202200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpert HP. Public acceptance of the mentally ill: An exploration of attitudes. Public Health Reports. 1969;84:59–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KW. Public opinion and the mental health parity debate: Lessons from the survey literature. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:1059–1066. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Stier A. Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:367–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Policy Research, U. o. C. National telephone survey of 1,341 adults conducted for the Institute for Health Policy and Health Services. University of Cincinnati; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen GA, Morrisey MA. Employer-sponsored insurance coverage for alcohol and drug abuse treatment, 1988. Inquiry. 1991;28:393–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: Labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los Angeles Times. National telephone survey of 1,682 adults. LA Times; 1994. Apr 22, [Google Scholar]

- McSween JL. The role of group interest, identity, and stigma in determining mental health policy preferences. Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law. 2002;27:773–800. doi: 10.1215/03616878-27-5-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Failure of health care reform in the USA. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 1996;1:4–9. doi: 10.1177/135581969600100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick EL, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Goldin D, Hodgkin D, Sciegaj M. Benefits in behavioral health carve-out plans of Fortune 500 firms. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:943–948. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Mental Health Association. Four More States Adopt Mental Health Parity. Message is Treatment Improves Functioning, Insurance Discrimination Doesn’t. 2008 http://www1.nmha.org/newsroom/system/news.vw.cfm?do=vw&rid=42.

- Ostrow L, Manderscheid R. Medicare and mental health parity. Health Affairs. 2009;28:922. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. ‘‘A disease like any other’’? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:1321–1330. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Princeton Survey Research Associates. National Telephone Survey of 1,200 adults conducted for the Harvard School of Public Health and the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck RA. Principles for priority setting in mental health services and their implications for the least well off. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:653–658. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N, Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV, Corrigan PW. Biogenetic models of psychopathology, implicit guilt, and mental illness stigma. Psychiatry Research. 2010;179:328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shern DL, Beronio KK, Harbin HT. After parity—what’s next. Health Affairs. 2009;28:660–662. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi AN, Swaminathan S, Mor V. Insurance parity and the use of outpatient mental health care following a psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:2879–2885. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B, Perry RP, Magnusson J. An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:738–748. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Meyerhoefer CD. State variations in the out-of-pocket spending burden for outpatient mental health treatment. Health Affairs. 2009;28:713–722. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]