Abstract

Objectives.

This study investigates the role of gender, caregiving, and marital quality in the correlation between widowhood and depression among older people within a European context by applying the theory of Social Production Functions as a theoretical framework.

Method.

Fixed-effects linear regression models are estimated using the first 2 waves (2004, 2006) of “The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe” (SHARE). A subsample of 7,844 respondents aged 50 and older in 11 countries, who were married at baseline and are either continuously married or widowed at follow-up, is analyzed.

Results.

Respondents who experienced widowhood between the 2 waves report significantly more depressive symptoms than those continuously married, with respondents living in Denmark and Sweden reporting a lower increase in depressive symptoms than those living in Greece, Spain, or Italy. There is no statistically significant interaction between gender and widowhood. Widowed persons who report higher marital quality at baseline show a larger increase in the number of symptoms of depression than those with low marital quality; widowed persons who report being a caregiver for their partner at baseline report smaller increase in the symptoms of depression compared with widowed noncaregivers.

Discussion.

The results support the results of previous studies using longitudinal data. Furthermore, the effect of widowhood varies among the 11 countries in the subsample although only a small amount of the variation in the increase of depressive symptoms after becoming widowed can be explained by such contextual factors.

Key Words: Aging, Depression, Europe, SHARE, Widowhood.

THE death of one’s spouse is one of the most devastating events in life. Previous research shows that becoming widowed is one of those life events that are most associated with negative stress (Dohrenwend, Krasnoff, Askenasy, & Dohrenwend, 1978; Holmes & Rahe, 1967). Many studies confirm that older widowed persons in particular report less well-being and more symptoms of depression than do their married counterparts (Lee, Willetts, & Seccombe, 1998; Umberson, Wortman, & Kessler, 1992; Williams & Umberson, 2004).

Previous research paid special attention to the question of whether widowhood has different effects on the onset of depression depending on gender (Lee & DeMaris, 2007). The question of whether men or women suffer more from depression after becoming widowed has still not been answered clearly. There are many studies that find indications that depressive symptoms are more pronounced for men (Carr, 2004b; Williams, 2003), whereas other studies show that women suffer more from depressive symptoms after becoming widowed (Chou & Chi, 2000; Lichtenstein, Gatz, Pedersen, Berg, & McClearn, 1996). However, other studies conclude that there are no gender differences in mental health after becoming widowed (Umberson et al., 1992).

Lee and DeMaris (2007) conjecture in their overview of the existing literature that the discrepancies in the results can be partly explained by the fact that some analyses have been conducted with cross-sectional data, whereas others have been carried out using longitudinal data. Cross-sectional data present the opportunity for collecting a broader range of elapsed time since widowhood, whereas longitudinal designs may censor time by design. On the other hand, longitudinal data provide a fuller opportunity to analyze both the antecedents and consequences of widowhood, whereas cross-sectional data may be hindered by recall bias.

The negative effect of becoming widowed is particularly strong during the first years after the event (Harlow, Goldberg, & Comstock, 1991; Mendes de Leon, Kasl, & Jacobs, 1994). The course of the psychological strain after becoming widowed follows a crisis model: Immediately after becoming widowed the effects are strongest, but they diminish with time due to coping processes. Some studies show that the levels of depression fall back to the level before the death of the partner after some years (Harlow et al., 1991; Mendes de Leon et al., 1994), whereas other studies find evidence that the level of depression diminishes with time but remains on an elevated level compared with the time before widowhood (Lee, DeMaris, Bavin, & Sullivan, 2001; Lee et al., 1998; Sonnenberg, Beekman, Deeg, & van Tilburg, 2000). As women on average report a longer duration of widowhood, women on average are in an advanced state of the crisis model in which the negative effects have lost their strength or have even vanished.

In addition, sample composition can have a significant effect on the results. Mortality rates are higher among widowed men compared with widowed women (Lusyne, Page, & Lievens, 2001). Additionally, mortality rates are higher among depressive persons (Mastekaasa, 1994). This selection bias cannot be controlled in cross-sectional studies and thus might lead to underestimating the levels of depression in men following widowhood. On the other hand, men are more likely to remarry after becoming widowed (Carr, 2004a) and thus take themselves out of the widowed population. However, remarriage is a rather rare event among the older population.

There is a wide variation in the extent of psychological consequences of widowhood, which depends—among other things—on marital quality. People who rate their marriage positively experience higher levels of psychological distress upon becoming widowed (Carr & Boerner, 2009; Carr et al., 2000).

Whether the surviving partner has provided care for the deceased one is also an important factor in the analysis of the mental health consequences of widowhood. Keene and Prokos (Keene & Prokos, 2008; Prokos & Keene, 2005) argue that while caregiving enhances levels of depression prior to widowhood, former caregivers experience widowhood as a less negative event because it is the end to a chronically stressful care situation. Furthermore, providing care might prepare the caregiver for the coming death of the spouse and allows “to say goodbye and (or) begin the grieving process before the death” (Keene & Prokos, 2008, p. 566). All this might lead to lower levels of psychological distress after becoming widowed for caregivers compared with noncaregivers.

However, it is not only individual characteristics that may account for differences in depression. As Ploubidis and Grundy show, depression rates vary considerably across Europe. “One possible factor underlying the observed country level variation might be the availability of state-provided supports and services, as these may be particularly important for mental health because the availability of state-provided safety nets may enhance feelings of security and reduce anxiety” (Ploubidis & Grundy, 2009, p. 674). There are influencing factors on the societal level that add to the differences in the number of depressive symptoms after widowhood among European regions or countries. One could assume, for example, that the magnitude of the effect of widowhood on depression varies with different patterns of domestic labor division (Hank & Jürges, 2007) and with the extent of economic independence of women within a society (Klement & Rudolph, 2004). One goal of this article is to contribute to the existing knowledge of the negative effects of widowhood on mental health within a European context from a longitudinal perspective using the “Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe” (SHARE). Although much research has been done in the field of mental health consequences of widowhood, little attention has been paid to differences in this effect between countries or regions.

As this indicative overview over the literature shows, widowhood and its effects on depression is a complex research field because there are many different aspects of widowhood, on the individual and societal level, which could possibly drive its associations with depressive symptoms or mental well-being in general. The aim of this article is to add to the understanding of the complex relationship between widowhood and changes in depressive symptoms by applying a longitudinal approach using European data. More specifically, this article contributes to the understanding of the association between widowhood and mental well-being by answering three specific questions: (a) Do men and women differ in the psychological consequences of widowhood? (b) What role do marital quality and caregiving play in the effect of widowhood on depression? (c) To what extent does widowhood increase levels of depression in the European context and are there differences in the association between widowhood and depression across Europe? The mechanisms that drive the deterioration in psychological well-being are considered under the social production function theory by Lindenberg in the remainder of this study.

Theoretical Framework—The Theory of Social Production Functions

What are the mechanisms that drive the deterioration in mental well-being after becoming widowed from a sociological point of view? In his work on social production function theory, Lindenberg (1989a, 1990, 1991) assumes that people are rational and goal directed. The universal goal that all people strive for is the production of psychological or emotional well-being. One’s level of psychological well-being is determined by physical well-being on the one hand and social well-being on the other. Physical and social well-being are universal needs, and their realization is dependent on the fulfillment of instrumental goals such as comfort and stimulation in order to produce physical well-being, and affection, behavioral confirmation, and status in order to produce social well-being. A lack of specific resources therefore hampers people in the production of well-being, which in turn might induce suffering from depressive symptoms. Thus, the social production function theory offers a fruitful theoretical approach to explain how sociodemographic differences affect the likelihood of suffering from depressive symptoms from a sociological point of view. Being married and living with a spouse is a powerful resource that can produce all instrumental goals, which in turn are necessary in order to produce well-being. Thus, losing one’s spouse will have severe consequences in the production of well-being. But which aspects of marriage produce comfort, stimulation, affection, behavioral confirmation, and status, and is there a gender difference in the production of the instrumental goals? A long tradition in research argues that marriage is more beneficial to men than to women. So far, the literature has shown that marriage offers a protective effect in terms of health, but this effect is stronger for men (Waite, 1995). The literature shows that men benefit from marriage by having a closer social connectedness (e.g., from sources outside the household because it is mainly wives who maintain the family’s social networks) and by receiving more emotional support and instrumental support (e.g., housework tasks) from a marriage (Lee et al., 1998; Umberson et al., 1992). However, a meta-analysis by Manzoli, Villari, Pirone, and Boccia (2007) reveals that despite these relative advantages for men as conferred by marriage, there is no difference between older men and women in the effect of marriage on mortality.

The Role of Gender

Marriage is an important resource for the production of comfort, affection, and stimulation for both genders, but especially for men, widowhood has a stronger impact on the production of these three instrumental goals:

Considering a traditional role allocation in the household, household managing tasks that have formerly been carried out by women form a special and unusual situation and therefore a potential source of strain for men (Utz, Reidy, Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, 2004; Williams, 2003). For women, on the other hand, the death of the husband does not result in drastic changes regarding household chores. Umberson and coworkers (1992) show that after becoming widowed, the number of hours spent on household tasks decreases for women but increases for men. Men, especially those from older cohorts, may be unprepared to take over those tasks producing comfort formerly carried out by their wives, which might lead to an increased feeling of strain for those men. Yet, Lopata (1973) argues that widowers may have greater economic resources, which enable them to purchase home-making services. In general, one can state that “[t]he more dependent the survivor, the higher the decrease in production capacity after the loss of the spouse and, as a consequence, the well-being of the respondent” (Nieboer et al., 1998, p. 117).

Having a spouse means having a person with whom “all kinds of things could be done, discussed and shared” (Nieboer et al., 1998, p. 119). Thus, marriage is beneficial in terms of stimulation for husbands and wives. However, because older women are typically socially more active than their husbands (Cornwell, 2011; McLaughlin, Vagenas, Pachana, Begum, & Dobson, 2010), it is easier for them to (partly) substitute the lost source for stimulation from within the marriage with resources for stimulation from outside the household.

Because wives often maintain friendships and close ties with children or other relatives, losing one’s spouse should result in a loss of affection from sources outside the household like friends, neighbors, and relatives for the surviving husband during the first couple of months of widowhood. However, men are more likely to compensate for the loss of affection by seeking new partners. Given the shortage of men in older age, women are less likely to receive affection from a new partner (Carr, 2004a).

Regarding the production of status and behavioral confirmation, it is especially women who gain from marriage and are thus hampered in the production of psychological well-being in the case of becoming widowed:

The loss of the spouse results in the loss of the most important source of behavioral confirmation for the surviving partner. Behavioral confirmation refers to the feedback one gets from relevant other following the compliance of social norms (such as caring for older family members). Older women in particular derive high levels of behavioral confirmation from caring for their husbands. If their husbands die, an important source of behavioral confirmation is lost. Due to demographic patterns, women are less likely to remarry and thus less likely to find a new source for gaining behavioral confirmation.

Becoming widowed might come along with status loss for the surviving partner because singles in general have a lower status in society than married people (Osterweis, Solomon, & Green, 1984). Financial strains are generally a threat to psychological well-being. Persons reporting not being able to make ends meet show elevated levels of depressive symptoms (Mirowsky & Ross, 2001). Women typically gain more from a marriage in financial terms because, even if holding constant human capital and occupational characteristics, men still earn more money and thus contribute more to the household income than women (see also current studies from the gender wage gap literature (Dex, Ward, & Joshi, 2008; Konstantopoulos & Constant, 2008)). Therefore, the death of a spouse is potentially a greater financial problem for widowed women than for widowed men, which should result in elevated levels of depression in widows compared with widowers (Angel, Douglas, & Angel, 2003; Ha, Carr, Utz, & Nesse, 2006; Umberson et al., 1992).

In summary, marriage facilitates the production of instrumental goals for men and women, and therefore, widowhood hampers men and women in the production of these goals. Whether it is women or men who gain more from marriage or who are hampered more severely by widowhood depends on the specific instrumental goal. Therefore, widowhood should be able to decrease psychological well-being for men and women to an equal extent. Only when focusing on the different aspects of widowhood, one should be able to find gender differences.

The Role of Marital Quality

Marriage is a strong resource, perhaps one of the strongest resources, for producing affection, stimulation, and behavioral confirmation—in cases where the marriage is characterized by a high-quality relationship. Having a spouse means having a person with whom “all kinds of things could be done, discussed and shared” (Nieboer et al., 1998, p. 119). Therefore, the dissolution of an emotionally strong and high-quality tie should have an extremely negative impact on the production of social well-being in terms of affection, stimulation, and behavioral confirmation from within the household. This assumption is supported by attachment theory, which states that if such a strong emotional tie is broken through death, severe psychological reactions are the result (Bowlby, 1980). Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, and Needham (2006) and Williams (2003) show that good marital quality is beneficial for the health of men and women. Carr and colleagues (Carr & Boerner, 2009; Carr et al., 2000) show that persons who reported high marital quality and rated their marriage positively experienced higher levels of negative psychological consequences after the death of their spouses.

The Role of Caregiving

Providing care for one’s partner or spouse is another important aspect of marriage, which is becoming more and more important in later life. If a spouse needs extensive care due to ill health, the caregiving partner has to dedicate much of his or her own time and effort into care and therefore might be restricted in his or her activities aimed at producing personal well-being (Nieboer et al.,1998). In accordance with the stress paradigm (Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981), this can result in elevated levels of psychological distress, especially if the caregiving activities exceed the caregiver’s abilities and resources. The literature shows that it is mostly wives who provide care for their husbands (Allen, 1994; Dentinger & Clarkberg, 2002; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006). Nieboer and coworkers (1998) show that spouses who provide care for their partner in need feel significantly more hampered in their activities, for example in those which produce stimulation, which in turn significantly reduces the well-being of caregivers. Although there is an elevated burden caring for loved ones while they are still alive, this burden disappears after becoming widowed. Although caregiving should enhance the levels of depressive symptoms while the care-receiving partner is still alive, long-term caregivers report lower levels of depression after the death of their spouses than noncaregivers and short-term caregivers, following a relief model (Keene & Prokos, 2008; Prokos & Keene, 2005). Caregiving is a chronically stressful situation for the caregiver. The death of the spouse also means the end of caregiver burden. Therefore, one might expect former caregivers to report somewhat lower levels of depression than noncaregivers after becoming widowed because the death of the spouse is not only a source of grievance but also a source of relief (as the caregiver burden does not exist anymore and the deceased spouse does not have to suffer anymore). One could also assume that for a caregiver the death of the spouse does not come unexpectedly, and thus, caregivers are able to “prepare” for this event, which in turn might result in less severe mental health consequences. On the other hand, persons caring for a spouse might derive a lot of behavioral confirmation from their spouses and from persons outside the household for their work, which has a positive impact on psychological well-being.

The Role of Cultural Contexts

One research goal of this article is to find out whether differences exist between countries regarding the effect of widowhood on depression. According to Lindenberg (1989b), social production functions vary in different cultural contexts, social positions, groups, or even time periods because it is social rules that define the situation-specific efficiency of the social production functions. Therefore, the production of instrumental goals through interaction with a spouse might be of different efficiency and importance for men and women in different countries. This could be due to either differences in welfare state regimes and policies and/or to differences in culturally determined gender roles. Although this study is able to identify regional differences, it is out of the scope of this article to test which of the two mechanisms is driving these differences.

Kohli, Kühnemund, & Lüdicke (2005) classify European countries into three clusters: countries with a traditional family structure (the Southern European countries), countries with a less traditional family structure (Scandinavian countries), and “in-between” countries (Central Europe). A traditional family structure is defined by the dominance of the male-breadwinner model, low female labor force participation, and low gender equity in the family (Crompton, 1999). In countries with traditional family structures, women depend heavily on the income of their spouses for the production of status, which leads to a status loss in the case of widowhood. Especially in Southern European countries, women have spent most of their lives outside the paid labor force and worked at home raising their children. Thus, a large proportion of widows rely on survivorship pension benefits as their main source of income. As survivorship pension benefits are always lower than the deceased spouse’s old-age pension, this results in a severe reduction in household income. However, a study by Ahn (2005) shows that the proportion of widows and widowers reporting to have more difficulties to make ends meet after becoming widowed is not significantly higher in Southern Europe compared with the rest of Europe.

As it is mainly wives who carry out household chores in countries with more traditional family structures, becoming widowed especially hampers widowers in the production of comfort. Thus, widowhood should be associated with more negative consequences for the surviving spouse in Southern Europe. However, Kohli and coworkers (2005) show that family ties (e.g., contact frequency with children, coresidence with adult children) are stronger in Spain, Italy, and Greece (compared, in particular, to the Scandinavian countries), and thus, widows and widowers living in Southern Europe might find it easier to replace their resource for affection from within the family. Replacing resources for the production of affection, stimulation, and behavioral confirmation from outside the family might be more likely in Scandinavian countries as active engagement in voluntary or charity activities and social connectedness among the generation aged 50 or older are higher in Northern Europe than in Southern Europe (Kohli, Hank, & Kunemund, 2009). All in all widows and widowers from Northern European countries are not as dependent on their spouses and have easier access to resources from outside the household, which facilitates the coping process. Therefore, one could expect widowhood to have less negative consequences for widows and widowers living in Northern European countries.

Methods

Statistical Model and Modeling Strategy

A straightforward way to investigate the psychological consequences of losing one’s spouse is to compare the mental health status of people before and after becoming widowed. This is only possible with panel data, where we observe the same individuals over time. The associations between social status or social roles and mental health might reflect social causation and social selection (Pearlin & Johnson, 1977). Although widowhood might seem a purely exogenous event at first sight, it might well be that depressive people, in particular, tend to marry persons who suffer from health problems (and thus have higher mortality risks). Therefore, research results will be biased if researchers do not control for pre-existing characteristics that influence both mental health and the likelihood of becoming widowed.

To test the effect of widowhood on depression, fixed-effects regression analysis is applied in order to exploit the panel structure of the data. An error-component model

| (a) |

(where γit is the dependent variable with i = entity and t = time; x it represents the independent variable with β1 as the coefficient for the independent variable, νi is the person-specific error, and εit is the idiosyncratic error) is averaged over time for each i:

| (b) |

Subtracting equation (b) from equation (a) results in

|

(c) |

which eliminates the person-specific error term νi.

The fixed-effects estimator presents the dependent variable y and the independent variable x in the form of their deviations from the person-specific mean. Thus, the statistical model allows within-person comparisons to be made (comparing the same person before and after becoming widowed) instead of between-person comparisons (comparing persons who are currently married with other persons who are currently widowed). A fixed-effects linear regression model allows controlling for time-constant unmeasured characteristics of individuals that might bias the association between widowhood and depression or are linked with depression. However, self-selection due to unmeasured time-variant factors cannot be ruled out by fixed effects. A disadvantage of fixed-effects regression is that it does not allow for the inclusion of time-invariant variables (e.g., gender). Thus, the main effects of time-invariant characteristics like gender and country cannot be analyzed. However, it is possible to include interactions with time-varying variables (e.g., interacting gender and widowhood and country and widowhood). Because the main effects of gender, marital quality, caregiving, and region on depression are not subject to the research questions (only their interaction with widowhood is of interest), the advantages of the fixed-effects approach outweigh the disadvantages.

Data Source

The data for this study are drawn from waves 1 (collected in 2004) and 2 (collected in 2006) of the “Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe” (SHARE; for an overview, see Börsch-Supan and Jürges (2005)). SHARE is modeled closely on the U.S. “Health and Retirement Study,” and it is the first data set to combine extensive cross-national information on the socioeconomic status, health, and family relationships of Europe’s elderly population. SHARE contains information from more than 45,000 computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) with individuals aged 50 and older. Eleven countries contributed to both waves: Sweden, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Spain, and Greece. Probability samples were drawn in each participating country. However, the institutional conditions with respect to sampling in the participating countries are so different that a uniform sampling design for the entire project is infeasible. As a result, the sampling designs used vary from a simple random selection of households (in the Danish case, e.g., from the country’s central population register) to rather complicated multistage designs (as, e.g., in Greece, where the telephone directory was used as a sampling frame). The weighted average household response rate in the face-to-face part of the survey is 62% (a thorough description of methodological issues is contained in the study by Börsch-Supan and Jürges (2005)). The overall attrition rate in wave 2 is 28% (see Schröder (2008)).

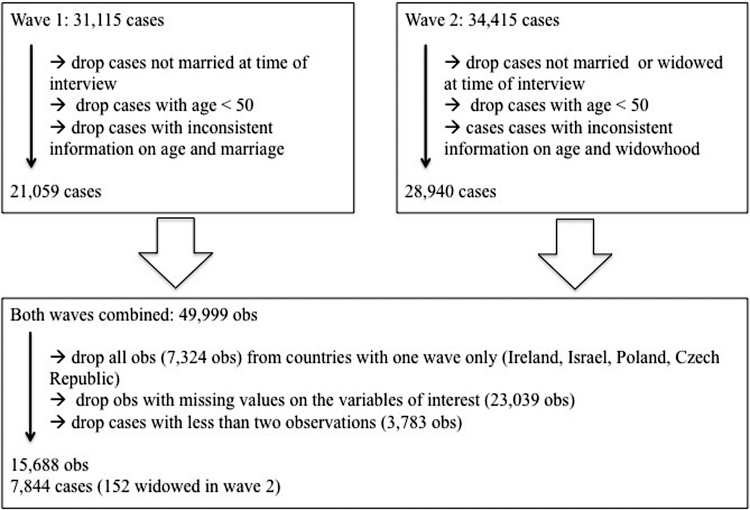

The analytical sample consists of 7,844 persons (see also figure 1). Wave 1 data—consisting of 31,115 observations—were reduced to those cases who were married at the time of the interview. Additionally, persons aged younger than 50 or of unknown age and persons who showed inconsistencies between age and duration of marriage were excluded from the sample. This reduced the wave 1 sample to 21,059 observations. Wave 2 data consisted of 34,415 observations. Of these, 915 observations had to be excluded due to age (younger than 50 years) or missing age information, or due to inconsistent information on widowhood. Because only persons who were either married or widowed in wave 2 remained in the sample, the number of observations was reduced to 28,940. The combined longitudinal data set thus consisted of 49,999 observations in total. Only observations with valid information on all variables of interest were included in the analysis. Some of these variables were asked in a self-completion drop-off questionnaire in wave 1, which was only handed to a random subsample in wave 1. Thus, a large fraction of the SHARE sample had to be dropped. Comparing the observations which remain in the analytical sample to the original SHARE sample shows that the analytical sample has lower levels of depression, is younger, slightly healthier, is more likely to being able to make ends meet, and is more likely to come from Northern Europe. However, there is no bias regarding gender, marital quality, and caregiving. Finally, only cases with observations in both waves remained in the sample. The attrition of cases, which only participated in wave 1 but did not continue their participation in wave 2, is unfortunately not random. Those who left the study are older, more depressed, are more likely to be caregivers, and report higher marital quality than those who participated again in wave 2. Additionally, they are more likely to come from Western or Southern European countries. Of those 7,844 remaining cases (15,688 observations), 152 became widowed between wave 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Analytical sample.

Key Variables

The primary outcome variable in all analyses is respondents’ state of mental well-being, measured by the number of depressive symptoms reported in the interview. This variable was operationalized using the EURO-D scale (Prince et al., 1999). The EURO-D scale has been developed for measuring the prevalence of depression among older people within a European context but has many similarities with the widely used CES-D scale (Radloff, 1977). The EURO-D scale ranges from zero (no symptoms of depression existent) to 12 (12 symptoms of depression existent). The symptoms are depressed mood, pessimism, suicidality, excessive feelings of guilt, sleeping problems, loss of interest, irritability, diminution in appetite, fatigue, difficulties in concentrating on entertainment or reading, lack of enjoyment in recent activities, and tearfulness. Respondents answer “yes” or “no” to questions about the presence of the aforementioned symptoms. All the items refer to the presence of those symptoms within the last month. Cronbach’s alpha for the EURO-D scale within SHARE is .79.

Widowhood, operationalized as a dummy variable for widowed (married is the reference category), is entered into the analyses as an explanatory variable. Because the fixed-effects regression model does not allow for time-invariant variables, a variable for gender would be automatically dropped from the analyses. But as it is possible to include an interaction effect of a time-variant with a time-invariant variable, an interaction effect of both gender and widowhood is part of the analyses in order to investigate gender differences. The interaction effect shows the changes in depressive symptoms for widowed women.

Respondents are also asked whether they are caregivers to their own spouses. This variable is also operationalized as a dummy variable for caregivers in wave 1 (with noncaregivers as the reference category). Because the information as to whether someone was a caregiver prior to becoming widowed can also be considered as time-invariant given that so far observations are available for two waves only, the multivariate analyses contain an interaction effect between caregiving and becoming widowed. This interaction effect can be interpreted as the changes in depressive symptoms within widowed caregivers.

An additive index of two variables serves as an indicator for marital quality: satisfaction with reciprocity within the relationship and conflicts with partner. The original variable ranges from 4 “strongly agree” to 0 “strongly disagree” (for reciprocity) and 0 “often” to 3 “never” for conflicts with partner. For the analyses, both variables are rescaled to have a mean of zero and a standard variation of 1 before adding them together. Positive values indicate marital quality above the mean, for example, a value of 0.5 indicates that the value for this person is half a standard variation higher than the mean value. Because both marital quality variables were measured only in wave 1, this additive index enters the multivariate analyses in the form of an interaction effect between marital quality and widowhood. This interaction effect shows the change in depressive symptoms depending on marital quality.

The analyses contain geographical region dummy variables for Southern Europe (Italy, Greece, and Spain), Northern Europe (Sweden and Denmark), and Western Europe (all other countries). This classification follows that of Erlinghagen and Hank (2006) and Kohli and coworkers (2005), reflecting the North–South gradient within Europe regarding traditional family structure, patterns of domestic labor division, female labor force participation, and volunteering activities and social connectedness. All time-invariant region dummies are interacted with widowhood.

The existing literature considers as well confirmed the fact that age, education, and chronic diseases are correlated with mental health. Prevalence of depression rises with age, persons suffering from chronic diseases are more likely to also suffer from depression (comorbidity), and persons with higher education are less likely to show symptoms of depression (Mirowsky & Ross, 2003). Thus, variables on age (in years) and the number of diagnosed physical chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, osteoporosis, high blood pressure, cancer, Parkinson’s disease) enter the analyses. In the age group considered here, education can be considered as time-invariant and is therefore disregarded in the fixed-effects regression. Income adequacy is measured using a question on whether respondents are able to make ends meet with their household income (Litwin & Sapir, 2009). The original variable ranges from 1 representing “with great difficulty” to 4 representing “easily.” The variable used in the analysis is dummy coded, with 0 indicating difficulties with the financial situation (therefore including the categories “with great difficulty” and “with some difficulty”) and 1 indicating respondents’ ability to make ends meet (including the categories “fairly easy” and easy”).

The regression models will only contain time-variant variables. Time-invariant variables (gender, caregiving at baseline, marital quality at baseline, region dummies) are dropped from the models. Only their interaction effects with widowhood are included. The regression coefficient of these interaction effects show how the “return” of these time-invariant variables changes for an individual when becoming widowed.

Results

Descriptive Findings

Table 1 shows some descriptive statistics. The applied data set contains information from 7,844 respondents. Of those, 7,692 respondents are continuously married and 152 became widowed during the two waves—103 women and 49 men. With regards to depressive symptoms, the four marital status/gender categories vary greatly. In general, continuously married men report the lowest number of depressive symptoms at baseline, whereas women, who later become widowed, have the highest number of depressive symptoms. At follow-up, too, married men report the lowest number of depressive symptoms, widowed women the highest number.

Table 1.

Means (SD) of the Sample for All Variables by Gender and Marital Status

| All | Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuously married | Married at baseline, widowed at follow-up | Continuously married | Married at baseline, widowed at follow-up | ||

| (n = 7,844) | (n = 3,722) | (n = 103) | (n = 3,970) | (n = 49) | |

| Individual indicators | |||||

| EURO-D (baseline) | 1.95 (1.99) | 2.38 (2.16) | 2.80 (2.45) | 1.53 (1.71) | 2.00 (2.14) |

| EURO-D (follow-up) | 1.95 (2.07) | 2.29 (2.16)a | 3.88 (2.51) | 1.57 (1.85)b | 3.04 (2.78) |

| Age (baseline) | 62.86 (8.52) | 61.53 (8.00)a | 67.63 (9.93)c | 63.87 (8.66)b | 72.92 (10.10) |

| Chronic diseases (baseline) | 1.40 (1.31) | 1.45 (1.34) | 1.66 (1.45) | 1.36 (1.28) | 1.41 (1.27) |

| Chronic diseases (follow-up) | 1.46 (1.36) | 1.50 (1.37)a | 1.89 (1.58) | 1.40 (1.33) | 1.57 (1.43) |

| Financial adequacy (baseline) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.69 (0.47) |

| Financial adequacy (follow-up) | 0.70 (0.46) | 0.70 (0.46) | 0.64 (0.48) | 0.71 (0.46) | 0.69 (0.47) |

| Caregiving (baseline) | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.20)a | 0.16 (0.36) | 0.04 (0.19)b | 0.18 (0.39) |

| Marital quality (baseline) | 0.00 (1.67) | −0.20 (1.77) | −0.20 (1.77) | 0.19 (1.56) | 0.52 (1.81) |

| Region indicators | |||||

| Region—North | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.20 (0.41) | 0.18 (0.38) | 0.12 (0.33) |

| Region—West | 0.53 (0.50) | 0.51 (0.50) | 0.54 (0.50) | 0.54 (0.50) | 0.63 (0.49) |

| Region—South | 0.29 (0.46) | 0.30 (0.46) | 0.25 (0.44) | 0.29 (0.45) | 0.25 (0.44) |

Note. aBonferroni multiple-comparison test: married women differ significantly from widowed women; p ≤ .05.

bBonferroni multiple-comparison test: married men differ significantly from widowed men; p ≤ .05.

cBonferroni multiple-comparison test: widowed women differ significantly from widowed men; p ≤ .05.

Source: SHARE release 2.5.

Married women versus widowed women.—

Widowed women and married women differ significantly regarding their number of depressive symptoms at follow-up but not at baseline. Widowed women are older than their married counterparts. Furthermore, they more often report being a caregiver for their spouse, and they report a higher amount of chronic diseases at follow-up. Counter intuitively, married and widowed women do not differ regarding their ability to make ends meet.

Married men versus widowed men.—

Widowed men and married men differ significantly regarding their number of depressive symptoms at follow-up but not at baseline. Widowed men are on average older than married men; they do not report more chronic diseases. Neither do widowed and married men differ in their reports on marital quality or financial hardship. On average, widowed men were caregivers for their spouses more often than were their married counterparts.

Widowed women versus widowed men—

Widowed women do not differ significantly from widowed men in most respects.

Fixed-Effects Regression Models

Table 2 shows the results of the fixed-effects regression models. The first model contains widowhood as an explanatory variable, with age, chronic conditions, and income adequacy as control variables. Growing older significantly decreases the number of depressive symptoms; suffering from more than two chronic conditions is associated with significantly worse mental health. Higher levels of income adequacy lead to reporting less symptoms of depression (regression coefficients for age, chronic conditions, and income adequacy not shown here). As expected, widowhood significantly increases the number of depressive symptoms by 1.078 units.

Table 2.

Fixed-Effects Regression Analyses for the Number of Depressive Symptoms

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widowhooda | 1.078*** (0.16) | 1.058*** (0.28) | 1.070*** (0.16) | 1.212*** (0.18) | 1.642*** (0.32) | 1.764*** (0.41) |

| Widowhood * Female | 0.031 (0.34) | 0.297 (0.35) | ||||

| Marital quality at baseline * widowhood | 0.268** (0.09) | 0.330*** (0.09) | ||||

| Caregiving at baseline * widowhood | −0.812† (0.43) | −1.158** (0.44) | ||||

| Northern Europe * widowhoodb | −1.340** (0.49) | −1.537** (0.50) | ||||

| Western Europe * widowhoodb | −0.569 (0.38) | −0.755* (0.38) | ||||

| Constant | 2.869*** (0.54) | 2.869*** (0.54) | 2.867*** (0.54) | 2.870*** (0.54) | 2.877*** (0.54) | 2.877*** (0.54) |

| R 2 (within) | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.023 |

| Number of cases | 7,844 | 7,844 | 7,844 | 7,844 | 7,844 | 7,844 |

| Number of observations | 15,688 | 15,688 | 15,688 | 15,688 | 15,688 | 15,688 |

Note. Regression coefficients; SEs in parentheses; all models controlled for age, number of chronic diseases, and income adequacy.

aContinuously married.

bSouthern Europe.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < 0.01. ***p < .001 (two-tailed test).

Source: SHARE release 2.5, Own Calculations.

Model 2 adds an interaction effect between widowhood and gender, but this interaction effect turns out to be insignificant. The increase in depression for respondents who became widowed between the two waves is comparable for men and women.

Model 3 interacts widowhood with marital quality. At zero marital quality, the effect of widowhood on average depression is positive with a coefficient of 1.070. That is, in marriages with average happiness levels, widowhood increases the levels of depression. At higher levels of marital quality, this effect becomes even stronger at a rate of 0.268 per unit. Widowhood has a more positive effect on depression the happier the marriage was.

Model 4 interacts widowhood with caregiving. For noncaregivers, the effect of widowhood on average depression is positive with a coefficient of 1.212. For caregivers, this effect becomes weaker by −0.812 units. However, this interaction effect turns out to be almost insignificant. In other words, widowhood increases the levels of depression for caregivers and noncaregivers to an almost comparable extent.

To test whether there are differences in the impact of widowhood on mental health across Europe, Model 5 adds interaction effects between European regions and widowhood, with Southern Europe serving as the reference category. The results indicate that there is some variation between countries. The effect of becoming widowed on average depression while living in Southern Europe is positive with a coefficient of 1.642. Becoming widowed while living in Northern Europe reduces this effect by −1.340 units. In other words, widowhood has a more positive effect on depression when living in Southern Europe. The interaction effect between widowhood and living in Western Europe is insignificant. Thus, widowhood has a comparable effect on depression for Western and Southern Europeans. Comparing the explained variance of Model 1 with the explained variance of Model 5, where region interaction effects were added, it can be concluded that only a very small amount of variance lies on the country level.

Model 6 is the full model, which includes all variables. Controlling for all variables does not change the overall results from the previous models. However, the coefficients for the interactions between widowhood and marital quality, widowhood and caregiving, and widowhood and region are larger than in the single models. The interaction effect between caregiving and widowhood becomes significant once the interaction effects between widowhood and gender, widowhood and marital quality, and widowhood and region are held constant. Furthermore, it turns out that there is also a significant difference between Western European countries and Southern Europe in the full model.

To sum up, one can conclude that widowhood in general is associated with higher numbers of depressive symptoms. Additionally, the analyses show that the negative experience of widowhood affects the levels of depression of men and women to a comparable extent. Widowed caregivers report a smaller increase in the number of symptoms of depression than noncaregivers, following a relief model. Although higher marital quality is usually associated with better mental health outcomes, widowed persons who experienced high marital quality show a larger increase in the number of depressive symptoms after the death of their spouse than widowed respondents who report lower marital quality. Widowhood is associated with a smaller increase in the number of depressive symptoms in Northern Europe and Western Europe compared with Southern Europe.

Discussion

The analyses show that widowhood is a negative event in life, and widowed persons show more depressive symptoms than married persons even when holding constant confounding factors. There seems to be no gender-specific effect of depression: Although women in general suffer from more depressive symptoms than men, widowhood has a comparable effect on men and women. This result is in line with some other studies using longitudinal data (see also Lee & DeMaris (2007)).

Umberson and coworkers (1992) stress the importance of gender-specific strains associated with widowhood. Although widowhood is an extremely distressing event for both genders, they conclude that widowhood affects men and women in very different ways. Because, for example, “the primary mechanism linking widowhood to depression among women is financial strain” and “[a]mong men the more critical mechanisms seem to be strains associated with household management” (Umberson et al., 1992, p. 10), further analyses should put more emphasis on those gender-specific strains resulting from widowhood.

Although this is out of the scope of this article, a straightforward way to test the assumption of gender-specific strains would be to implement three-way interactions between gender, widowhood, and financial adequacy. Preliminary analyses (not shown here) assume that financial hardship seems to increase the number of depressive symptoms more for widowed men than for widowed women. Although the SHARE data does not offer the information on how much time is spent doing housework, the information on who is mainly responsible for doing the household chores is available. Further analyses should also incorporate this information interacted with gender to see whether household management is a possible mechanism to identify some gender differences in the increase of depressive symptoms following widowhood.

Putting more emphasize on the importance of gender-specific strains is also in line with the results of Nieboer and coworkers (1998), who find that the production of psychological well-being through instrumental goals deteriorates differently for men and women in widowhood, but after a certain period of time, the difference in well-being between widowed men and widowed women vanishes. Future analyses should specifically control for the different aspects of marriage and widowhood, which have gender-specific impact on the production of status, comfort, behavioral confirmation, affection, and stimulation.

Marital quality and caregiving moderate the association between widowhood and depressive symptoms. Although the direct effects of marital quality and caregiving cannot be analyzed in the fixed-effects models, the significant interactions between marital quality and widowhood on the one hand and caregiving and widowhood on the other support previous studies by Carr and coworkers (2000), Carr and Boerner (2009), Prokos and Keene (2005), and Keene and Prokos (2008), which find that widowhood has even more negative psychological consequences for those who rate their marriage positively but has less a negative impact on those who provide care to their spouse before their death. Some preliminary analyses (not shown here) suggest that with regards to caregiving and marital quality, there is no difference between men and women in the psychological reaction to widowhood. Especially with regards to caregiving, future studies should further analyze the impact of the duration of caregiving (short term vs. long term), the amount of time spent for providing care, the kind of caregiving tasks carried out, and whether the caregiving spouse receives additional help from other sources from inside or outside the household.

Although there is a significant difference between Northern Europeans and Southern Europeans in the increase of depressive symptoms after becoming widowed, only a small amount of the variation in the increase of depressive symptoms after becoming widowed can be explained by contextual factors, such as the regions the respondents live in. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to find out whether it is different social welfare policies that drive this difference between European region or whether it is different cultural gender roles that account for differences between countries and regions. Further analysis should specifically test these two different mechanisms. Another interesting question that is yet to be answered is whether there are regional effects regarding gender differences in the psychological reaction to widowhood.

Social support, either by family or friends (Ha et al., 2006; Onrust, Cuijpers, Smit, & Bohlmeijer, 2007) constitutes an important resource regarding psychological well-being after widowhood. Many studies prove that within Europe many different regional patterns of familial relations and support exist (Glaser, Tomassini, & Grundy, 2004). Further analyses should try to find out if and how these differences in social support influence depression levels after becoming widowed. Studies also show that volunteer work buffers against the negative aftermaths of widowhood (Li, 2007). Therefore, further analyses should also incorporate other aspects such as social networks and family relations.

This study has several limitations. The analyses have been conducted with the first and second wave of the “Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe” (SHARE). The number of respondents who lost their spouses between the waves is still very small. This small number becomes problematic once we compare different countries because the number of widowed respondents in each single country is extremely small.

Additionally, the division of the respondents into continuously married and widowed between the waves might be insufficient as it only covers the marital status since 2004. It is possible that some of the persons who were married in 2004 have been widowed before and have remarried before the first interview in 2004 was conducted. Therefore I cannot rule out the possibility that some of those in the married group had recovered from being widowed and remarried.

Of those who have been widowed, I only use the information that they became widowed between the two waves but not exactly when the event happened. But the course of the psychological strain after becoming widowed follows a crisis model. This could lead to problems, as very recently widowed respondents are not distinguished from those who have been widowed for almost 2 years.

The large reduction of the sample size (SHARE original sample vs. analytical sample) constitutes another important limitation. Firstly, a very small sample size makes it more difficult to detect significant association. Secondly—and more importantly—such a large reduction of the sample might lead to biases because reductions due to panel attrition and item nonresponse are often not random. As the analyses showed, there is a bias in the analytical sample compared with the original sample. The analytical sample less depressed, younger, financially better off, and healthier than the original sample. Therefore, one has to be very careful when trying to generalize the results.

The goodness-of-fit measure R 2-within seems to be very small. Indeed, it is much smaller than in standard OLS regressions. It can be interpreted as the amount of time variation in depression, which is explained by variation over time in the independent variables. In contrast to OLS regression R 2, the fixed effects R 2-within neglect the explanatory effects of the intercept and thus does not quantify the overall effect of groups on the model fit.

Although this study applies the social production function theory as a theoretical framework, which can explain the mechanisms that translate socioeconomic status into mental well-being, there are also other theories that have been applied in other studies. Among them are role theory, attachment theory, and the stress paradigm—just to mention three prominent examples. Further studies should try to incorporate those theories in order to explain the psychological consequences of widowhood from different angles and thus get to a better and more complete understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

This article is the first analysis of psychological consequences of widowhood among older persons using the SHARE data. The number of cases who became widowed during the waves is still very small, which does not allow for detailed analyses of the different gender- or region-specific strains associated with widowhood. For this reason, the analyses presented here can only provide a first impression. With more and more waves of SHARE in the future, the number of widowed respondents will grow, and more detailed analyses of the variance of the effect of widowhood within a European context from a comparative perspective will be possible.

Funding

This article uses data from SHARE release 2.5.0, as of May 24, 2011. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through the 5th framework programme (project QLK6-CT-2001- 00360 in the thematic programme Quality of Life), through the 6th framework programme (projects SHARE-I3, RII-CT- 2006-062193, COMPARE, CIT5-CT-2005-028857, and SHARELIFE, CIT4-CT-2006-028812), and through the 7th framework programme (SHARE-PREP, 211909 and SHARE-LEAP, 227822). Additional funding from the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01 AG09740-13S2, P01 AG005842, P01 AG08291, P30 AG12815, Y1-AG-4553-01 and OGHA 04-064, IAG BSR06-11, R21 AG025169) and from various national sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org for a full list of funding institutions).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Karsten Hank, Hendrik Jürges, Mathis Schröder, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

References

- Ahn N. (2005, March) Financial consequences of widowhood in Europe. Cross-Country and gender differences. (CEPS ENEPRI Working Papers No. 32). European Network of Economic Policy Research Institutes. Brussels, Belgium.

- Allen S. M. (1994). Gender differences in spousal caregiving and unmet need for care. Journal of Gerontology, 49, S187–S195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel J. L., Douglas N., Angel R. J. (2003). Gender, widowhood, and long-term care in the older Mexican American population. Journal of Women & Aging, 15, 89–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A., Jürges H. (Eds.) (2005). The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe—Methodology. Mannheim: MEA; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1980). Attachment and loss. New York, NY: Basic Books; [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. (2004a). The desire to date and remarry among older widows and widowers. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66, 1051–1068 [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. (2004b). Gender, preloss marital dependence, and older adults’ adjustment to widowhood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66, 220–235 [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., Boerner K. (2009). Do spousal discrepancies in marital quality assessments affect psychological adjustment to widowhood? Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 495–509 [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., House J. S., Kessler R. C., Nesse R. M., Sonnega J., Wortman C. (2000). Marital quality and psychological adjustment to widowhood among older adults: A longitudinal analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K. L., Chi I. (2000). Stressful events and depressive symptoms among old women and men: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 51, 275–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B. (2011). Independence through social networks: Bridging potential among older women and men. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 782–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton R. (Ed.) (1999). Restructuring gender relations and employment. The decline of the male breadwinner. New York: Oxford University Press; [Google Scholar]

- Dentinger E., Clarkberg M. (2002). Informal caregiving and retirement timing among men and women—Gender and caregiving relationships in late midlife. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 857–879 [Google Scholar]

- Dex S., Ward K., Joshi K. (2008). Gender differences in occupational wage mobility in the 1958 cohort. Work Employment and Society, 22, 263–280 [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B. S., Krasnoff L., Askenasy A. R., Dohrenwend B. P. (1978). Exemplification of a method for scaling life events: The Peri Life Events Scale. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19, 205–229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlinghagen M., Hank K. (2006). The participation of older Europeans in volunteer work. Ageing & Society, 26, 567–584 [Google Scholar]

- Glaser K., Tomassini C., Grundy E. (2004). Revisiting convergence and divergence: Support for older people in Europe. European Journal of Ageing, 1, 64–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha J. H., Carr D., Utz R. L., Nesse R. (2006). Older adults’ perceptions of intergenerational support after widowhood: How do men and women differ? Journal of Family Issues, 27, 3–30 [Google Scholar]

- Hank K., Jürges H. (2007). Gender and the division of household labor in older couples: A European perspective. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 399–421 [Google Scholar]

- Harlow S. D., Goldberg E. L., Comstock G. W. (1991). A longitudinal study of the prevalence of depressive symptomatology in elderly widowed and married women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 1065–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes T. H., Rahe R. H. (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene J. R., Prokos A. H. (2008). Widowhood and the end of spousal care-giving: Relief or wear and tear? Ageing & Society, 28, 551–570 [Google Scholar]

- Klement C., Rudolph B. (2004). Employment patterns and economic independence of women in intimate relationships: A German-Finnish comparison. European Societies, 6, 299–318 [Google Scholar]

- Kohli M., Hank K., Kunemund H. (2009). The social connectedness of older Europeans: Patterns, dynamics and contexts. Journal of European Social Policy, 19, 327–340 [Google Scholar]

- Kohli M., Kühnemund H., Lüdicke J. (2005). Family structure, proximity and contact. In Börsch-Supan A., Brugiavini A., Jürges H., Mackenbach J., Siegrist J., Weber G. (Eds.), Health, ageing and retirement in Europe – First results from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. (p. 164). Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging (MEA) [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulos S., Constant A. (2008). The gender gap reloaded: Are school characteristics linked to labor market performance? Social Science Research, 37, 374–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. R., DeMaris A. (2007). Widowhood, gender, and depression: A longitudinal analysis. Research on Aging, 29, 56–72 [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. R., DeMaris A., Bavin S., Sullivan R. (2001). Gender differences in the depressive effect of widowhood in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56, 56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. R., Willetts M. C., Seccombe K. (1998). Widowhood and depression: Gender differences. Research on Aging, 20, 611–630 [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. (2007). Recovering from spousal bereavement in later life: Does volunteer participation play a role? The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, 257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P., Gatz M., Pedersen N. L., Berg S., McClearn G. E. (1996). A co-twin–control study of response to widowhood. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51, 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg S. M. (1989a). Choice and culture: The behavioral basis of cultural impact on transactions. In Haferkamp H. (Ed.), Social structure and culture, (pp. 175–200). Berlin: de Gruyter; [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg S. M. (1989b). Social production functions, deficits, and social revolutions: Prerevolutionary France and Russia. Rationality and Society, 1, 51–77 [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg S. M. (1990). Homo socio-oeconomicus: The emergence of a general model of man in the social sciences. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 146, 727–748 [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg S. M. (1991). Social approval, fertility and female labour market behaviour. In Siegers J., De Jong-Gierveld J., Van Imhoff E. (Eds.), Female labour market behaviour and fertility: A rational choice approach, (pp. 32–58). Berlin/New York: Springer Verlag; [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H., Sapir E. V. (2009). Perceived income adequacy among older adults in 12 countries: Findings from the survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. The Gerontologist, 49, 397–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopata H. Z. (1973). Widowhood in an American city. Anonymous Cambridge, MA: Schenkman; [Google Scholar]

- Lusyne P., Page H., Lievens J. (2001). Mortality following conjugal bereavement, Belgium 1991-96: The unexpected effect of education. Population Studies, 55, 281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoli L., Villari P., Pirone G. M., Boccia A. (2007). Marital status and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 64, 77–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastekaasa A. (1994). Marital status, distress, and well-being: An international comparison. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 25, 183–205 [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin D., Vagenas D., Pachana N. A., Begum N., Dobson A. (2010). Gender differences in social network size and satisfaction in adults in their 70s. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 671–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes de Leon C., Kasl S. V., Jacobs S. (1994). A prospective study of widowhood and changes in symptoms of depression in a community sample of the elderly. Psychological Medicine, 24, 613–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J., Ross C. E. (2001). Age and the effect of economic hardship on depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, 132–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J., Ross C. E. (2003). Social causes of psychological distress, (2nd ed.). New York, NY: de Gruyter; [Google Scholar]

- Nieboer A. P., Lindenberg S. M., Ormel J. (1998). Conjugal bereavement and well-being of elderly men and women: A preliminary study. Omega-Journal of Death and Dying, 38, 113–141 [Google Scholar]

- Nieboer A. P., Schulz R., Matthews K. A., Scheier M. F., Ormel J., Lindenberg S. M. (1998). Spousal caregivers’ activity restriction and depression: A model for changes over time. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 47, 1361–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onrust S., Cuijpers P., Smit F., Bohlmeijer E. (2007). Predictors of psychological adjustment after bereavement. International Psychogeriatrics/IPA, 19, 921–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweis M., Solomon F., Green M. (Eds). (1984). Bereavement: Reactions, consequences and care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Johnson J. S. (1977). Marital status, life-strains and depression. American Sociological Review, 42, 704–715 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Lieberman M. A., Menaghan E. G., Mullan J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., Sörensen S. (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploubidis G. B., Grundy E. (2009). Later-life mental health in Europe: A country-level comparison. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64, 666–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. J., Reischies F., Beekman A. T., Fuhrer R., Jonker C., Kivela S. L. … Copeland J. R. (1999). Development of the EURO-D scale–a European, Union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 174, 330–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokos A. H., Keene J. R. (2005). The long-term effects of spousal care giving on survivors’ well-being in widowhood. Social Science Quarterly, 86, 664–682 [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401 [Google Scholar]

- Schröder M. (2008). Attrition. In Börsch-Supan A., Brugiavini A., Jürges H., Kapteyn A., Mackenbach J., Siegrist J., Weber G. (Eds.), Health, ageing and retirement in Europe (2004–2007). Starting the longitudinal dimension, (pp. 327–332). Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging (MEA) [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg C. M., Beekman A. T., Deeg D. J., van Tilburg W. (2000). Sex differences in late-life depression. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 101, 286–292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., Williams K., Powers D. A., Liu H., Needham B. (2006). You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., Wortman C. B., Kessler R. C. (1992). Widowhood and depression: Explaining long-term gender differences in vulnerability. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 10–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz R. L., Reidy E. B., Carr D., Nesse R., Wortman C. (2004). The daily consequences of widowhood: The role of gender and intergenerational transfers on subsequent housework performance. Journal of Family Issues, 25, 683–712 [Google Scholar]

- Waite L. J. (1995). Does marriage matter? Demography, 32, 483–507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. (2003). Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage, and psychological well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 470–487 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K., Umberson D. (2004). Marital status, marital transitions, and health: A gendered life course perspective. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 45, 81–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]