Abstract

This paper analyzed the existing literature on risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence among Hispanics using the four-level social-ecological model of prevention. Three popular search engines, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Google Scholar, were reviewed for original research articles published since the year 2000 that specifically examined factors associated with intimate partner violence (IPV) among Hispanics. Factors related to perpetration and victimization for both males and females were reviewed. Conflicting findings related to IPV risk and protective factors were noted; however, there were some key factors consistently shown to be related to violence in intimate relationships that can be targeted through prevention efforts. Future implications for ecologically-informed research, practice, and policy are discussed.

Keywords: Domestic violence, violence prevention, risk factors, protective factors, victimization

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as physical, emotional, psychological, verbal, and/or sexual abuse between two individuals engaged in a current or previous romantic relationship (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008). It is a widespread public health problem impacting millions of women and men in the U.S. each year and can have long-lasting physical and psychological effects on not only the individuals involved in the act(s) of violence, but also on families and communities at large. Given the harmful effects associated with IPV, the CDC (2008, 2011) and National Center for Victims of Crime (NCVC, 2011) have recognized the lack of knowledge surrounding IPV prevention and the urgency in better understanding the factors associated with IPV so as to lead to more effective prevention efforts.

Social-ecological models that explain the risk and protective factors associated with violence and guide prevention efforts have recently been developed (Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002; World Health Organization [WHO], 2010) and have become the “gold standard” in violence prevention (CDC, 2009). Although existing models summarize the findings from the general violence research area, it important to develop tailored social-ecological models that are specific to race/ethnicity and the type of violence being addressed, as predictors of IPV have been found to differ according to these classifications (Aldarondo & Castro-Fernandez, 2011; Aldarondo, Kaufman Kantor, & Jasinski, 2002; Cunradi, Caetano, & Schafer, 2002; Krug et al., 2002). The development of these tailored social-ecological models will allow researchers, program developers, practitioners, and policy makers make more culturally informed and evidence-based decisions to address violence across communities in the U.S. Furthermore, a recent review of risk and protective factors for the perpetration of domestic violence by Aldarondo and Castro-Fernandez (2011) highlights the need for further research on factors predicting violence, how they may be related or change over time, and how they may vary across different racial/ethnic groups. This paper seeks to develop a social-ecological understanding of the risk and protective factors associated with IPV among Hispanics.

Background

IPV among Hispanics

Hispanics are the largest and fastest growing population in the U.S. at present. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau (2010) reported that Hispanics accounted for more than half of the total population growth between 2000 and 2010. More specifically, in 2010 Hispanics accounted for approximately 50.5 million people in the population. The Hispanics represent nearly 16% of the total population and this is estimated to increase to about 25% of the population by the year 2050. Although the terms Hispanic and Latino are broad and encompass heterogeneous subgroups of the population, they are currently the terms utilized by the American government to refer to individuals whose heritage or country of origin includes Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, South or Central America, or other Spanish cultures regardless of race, with the first three countries representing the largest subgroups, respectively (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

Although there have been inconsistencies and gaps in the literature in regards to whether higher rates of IPV exist among Hispanics after controlling for socioeconomic status, recent studies on health disparities provide evidence that Hispanics are disproportionately affected by IPV (Caetano, Field, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2005; Tjanden & Theonnes, 2000). Given the predominant presence of Hispanics in the population, addressing this health disparity through prevention and intervention work is critical. In a large national study of cohabitating couples, a higher incidence of IPV was noted among Hispanic couples (14%) in comparison to non-Hispanic White couples (6%), even after controlling for socioeconomic status. Hispanics also reported a higher recurrence of IPV (58%) than both non-Hispanic Black (52%) and White (37%) couples (Caetano et al., 2005).

Hispanics have also been found to be more vulnerable to the consequences of IPV; for example, Hispanic female victims of IPV are more likely to experience poor mental health outcomes and have suicidal ideation than non-Hispanic female victims (Bonomi, Anderson, Cannon, Slesnick, & Rodriguez, 2009; Krishnan, Hilbert, & Pase, 2001). A study of femicides, murders of females, in Massachusetts over a 14-year-period found that Hispanic women were at disproportionately higher risk of being killed by a partner than non-Hispanic women (Azziz-Baumgartner, McKeown, Melvin, Dang, & Reed, 2011). Demographic and culture-related factors that are common in the Hispanic population, such as young age, perceived/actual isolation, levels of acculturation, language barriers, increased unemployment, and a belief in traditional gender norms (CDC, 2008; Cunradi, 2009) may account for the vulnerability to IPV, including increased incidence and more adverse health consequences of IPV among this population (Aldarondo et al., 2002; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

The social-ecological framework

The CDC (2009) states that the first step to preventing violence is to understand it. They use a four-level social-ecological model as a framework for violence prevention, indicating that clarifying the factors that increase risk for violence will lead to better prevention efforts (adapted from Krug et al., 2002). The first level is individual, which includes demographic and personal history factors that may lead to increased risk for victimization or perpetration of violence (CDC, 2009; Krug et al., 2002). At the second level are relationship factors that increase risk for violence. These include relationships such as intimate partners, family members, and peers and the ways in which they may contribute to risk for violence. Community-level factors such as school settings, workplaces, and neighborhoods comprise the third level of this framework. The community is the level in which relationships exist and are embedded. Finally, the fourth level of the socio-ecological model includes larger societal factors such as norms, policies, and inequalities and the way in which they create a climate where violence can occur. Researchers have found this model useful for understanding the etiology of domestic violence more broadly (Aldarondo & Castro-Fernandez, 2011). Furthermore, this model may provide a beneficial method for conceptualizing the prevention of IPV specifically among Hispanics.

Current Study

The purpose of this article is to review the literature that has been published since the year 2000 highlighting risk and/or protective factors among Hispanics who have experienced or perpetrated IPV in the United States using the CDC’s four-level social-ecological model of prevention (CDC, 2009; Krug et al., 2002). More specifically, we utilize a social-ecological framework of violence to examine risk and protective factors at the individual, relationships, community, and societal levels. The aim in identifying risk and protective factors unique to Hispanics who experience IPV is to gain a better understanding of what this problem looks in the majority subpopulation in the U.S., highlight what is unknown in the field that may contribute to the findings regarding health disparities and guide researchers in developing effective multi-level prevention and intervention strategies. The study types/designs, sample size and characteristics, and results found in studies describing the etiology of IPV among Hispanics are reviewed. Finally, recommendations for integrating dimensions of the social-ecological model of prevention for IPV into research, practice, and policy are provided.

Method

Procedure

This review of the literature focused on locating, summarizing, and synthesizing research studies that identified risk and/or protective factors associated with the victimization or perpetration of IPV among Hispanics in the U.S. Three major databases, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar, were used to identify potential studies. The following search terms were used in different combinations: intimate partner violence, domestic violence, family violence, femicide, gender-based violence, sexual assault, partner violence, Hispanic, Latino, risk and protective factors. Inclusion criteria for the publication included: (a) being an original research study, (b) describing the relationship between a risk and/or protective factor and IPV, (c) including a sample in which the majority was Hispanic or describing and including an analysis strategy that examined groups by Hispanic ethnicity, and (d) a publication date of 2000 or more recent.

The socio-ecological model of violence underscores the important role that societal level factors such as policies and culture can play on the occurrence of IPV (CDC, 2009). Because history can have a profound impact on these societal level factors, this review utilized 2000 as the cutoff date to provide a review of recently published research articles since the beginning of the new millennium. A decision regarding using the publication date rather than the data collection date was made because many articles did not include a date documenting the data collection period, and thus, this would have been difficult to control.

A review of the literature was performed in October 2011 using 14 different combinations of the keywords provided. First, PsycINFO was reviewed, generating numerous articles. After reviewing the abstracts of these articles, 26 articles were retrieved, 18 of which met all inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Next, PubMed was reviewed. This search engine contributed to 11 additional articles, 7 of which met inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Lastly, Google Scholar was searched and 4 articles were identified as meeting inclusion criteria. As a result, a total of 29 articles met inclusion criteria and were included in this review (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of Literature Review

| Study | Sample Size and Characteristics | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aldarondo, E., Kaufman Kantor G., & Jasinski, J.L. (2002). A risk marker analysis of wife assault in Latino families. Violence Against Women, 8, 429–454. | (N = 846) Hispanics, sub-sample from 1992 National Alcohol and Family Violence Survey. Couples who were married or cohabitating. Mean age of men was 45.3 years and of women was 42.6 years. Median family income $25,000 to $29,000 annually. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual interviewers. Measures: Predictors-age, violence approval, alcohol consumption, verbal aggression scale of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1990), relationship conflict, experiencing violence in family origin, family income, employment, occupational status, marital status Outcomes-CTS-Male perpetrated wife assault (Straus, 1990) |

The study concluded that for native Mexican, Mexican-American, and Puerto Rican, and Mexican men, relationship conflict was the strongest predictor of wife assault. Experiencing violence in the family of origin was also related to increased risk of wife assault for Mexican men, whereas for Mexican-American men lack of economic resources was associated with increased rates of wife assault. |

| Bell, N.S., Harford, T.C., Fuchs, C.H., McCarroll, J.E., & Schwartz, C.E. (2006). Spouse abuse and alcohol problems among White, African American, and Hispanic U. S. Army soldiers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 1721–1733. | (N =24,998) Convenience sample of active duty enlisted soldiers in the U. S. Army who had abused a spouse and were listed in the Army’s Central Registry database and all married enlisted male soldiers on active duty (controls, N =64,442) between the years of 1991–98 who had completed the Health Risk Appraisal | Quantitative, cross-sectional, self-report questionnaire and incident report and analysis of secondary data. Measures: Predictors-alcohol problems (CAGE Questionnaire; Ewing, 1984), alcohol consumption patterns, psychosocial factors (social support, depression, social, family problems), demographic factors (age, race/ethnicity, rank, education, number of months in grade, number of dependents), perpetrator drinking during spouse abuse incident Outcomes-Entry in the Army Central Registry of child and spouse abuse database |

Researchers found that risk factors for abuse perpetration by enlisted male soldiers included heavy weekly alcohol consumption (15 or more drinks), having less than a college education, having 4 or more dependents, and a self-report of family conflict. |

| Caetano, R., Cunradi, C. B., Clark, C. L., & Schafer, J. (2000). Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among White, Black and Hispanic couples. Journal of Substance Abuse, 11(2), 123–138. | (N = 527) Random probability sample of U. S. households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-drinking 5 or more drinks on occasion (Cahalan, Roizen, & Room’s 1976 index), control measures including sociodemographic characteristics and psychological/psychosocial variables (approval of marital aggression, impulsivity, childhood violence victimization) Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of Female to Male Partner Violence (FMPV) and Male to Female Partner Violence (MFPV; Straus, 1990) |

MFPV was found to be highest when participants reported a household income less than $20,000 annually, male unemployment, female classified as infrequent drinker, and a high level of male impulsivity. Protective factors identified included being married, retired, female employment, and low alcohol use for men. FMPV risk factors included higher levels of male impulsivity and low levels of education. Protective factors included females being of older age and being retired. |

| Caetano, R., Ramisetty-Mikler, S., & Harris, R. (2010). Neighborhood characteristics as predictors of male to female and female to male partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 1986–2009. | (N = 387) Random probability sample of households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-neighborhood, education, unemployment, working-class composition, perceived social cohesion (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997), perceived informal social control (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997), quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption and binge drinking, sociodemographic characteristics (ethnic identification, age, income) Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Neighborhood poverty was significantly correlated with IPV. Social cohesion and social control were not correlated with IPV. |

| Caetano, R., Nelson, S., & Cunradi, C. (2010). Intimate partner violence, dependence symptoms and social consequences from drinking among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. American Journal of Addictions, 10, S60-S69. | (N = 527) Random probability sample of U. S. households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-alcohol consumption, alcohol problems, drug use, sociodemographic data, attitudes towards aggression, impulsivity Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Bivariate results showed that risk factors for both MFPV and FMPV among Hispanics included dependence-related problems, social consequences from drinking and drug use. According to multivariate results, alcohol-related problems and drug use were not related to IPV among Hispanics. Risk factors for MFPV included men’s unemployment, women’s impulsivity, and women’s weekly volume of alcohol consumed. For FMPV, education was a protective factor for women whereas male impulsivity, age, and income between $10,000 and $20,000 were risk factors. |

| Caetano, R., Ramisetty-Mikler, S., & McGrath, C. (2004). Acculturation, drinking, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the United States: A longitudinal study. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 26(1), 60–78. | (N = 387) Random probability sample of households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, longitudinal study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-sociodemographic variables including ethnic identification, couple acculturation categorized as low-low, low-medium, low-high, medium-high, high-high (Caetano, 1987); quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption; alcohol problems; psychosocial variables (childhood violence victimization, childhood exposure to parental violence, impulsivity, approval of marital aggression) Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Risk factors for MFPV in2000 included FMPV and MFPV in 1995 and Male impulsivity. Protective factors from MFPV included women being between the ages of 40–49 and high-medium levels of U. S. acculturation. Risk factors for FMPV in 2000 included the presence of FMPV in 1995. Protective factors for FMPV were female unemployment/homemaker status and an increase in men’s volume of alcohol consumption per week. |

| Caetano, R., Schafer, J., Clark, C., Cunradi, C., & Rasberry, K. (2000). Intimate partner violence, acculturation, and alcohol consumption among Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 15, 30–45. | (N = 527) Random probability sample of U. S. households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-acculturation, alcohol consumption as measured by the Quantity-Frequency Index (Cahalan, Roizen, & Room, 1976), age, gender, income, education, marital status, childhood violence victimization, approval of marital aggression, impulsivity Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Men and women were organized into low, medium, and high acculturation groups and results were analyzed by category. MFPV and FMPV were highest among the medium acculturation group. Across all groups, risk factors for MFPV included childhood victimization, infrequent drinking by women, and impulsivity in women. Protective factors against MFPV included females between the ages of 40 and 40, income between $20,000 and $29,999 or above $40,000, being married, and couple members who are less frequent drinkers. Risk factors for FMPV included female childhood victimization, frequent alcohol consumption by men, and impulsivity in men. Protective factors included family income between $20,000 and $30,000 and women being older than 40 years. |

| Caetano, R., Schafer, J., & Cunradi, C.B. (2001). Alcohol-related intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(1), 58–65. | (N = 527) Random probability sample of households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption, alcohol problems, ethnic identification Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Male alcohol-related problems were associated with an increased occurrence of MFPV and FMPV. Hispanics were 2 times more likely to report FMPV when living in impoverished neighborhoods. |

| Castro, R., Peek-Asa, C., Garcia, L., Ruiz, A., & Kraus, J.F. (2003). Risks for abuse against pregnant Hispanic women Morelos, Mexico and Los Angeles County, California. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 325–332. | (N = 1,133) Hispanic women in their third trimester of pregnancy in Morelos, Mexico (N = 914) or Los Angeles, CA (N = 219). | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-sociodemographic characteristics, reproductive history, history of current and past abuse Outcomes-incidence of emotional, sexual, and physical abuse within the past year (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) |

Women in CA reported changes in the rate of abuse during pregnancy, 9.1% increase and12.8% decrease. For all types of violence in both countries, women reported a decrease in violence (sexual and physical abuse) during pregnancy, but an increase in emotional abuse. Risk factors for women in Mexico included age (19-years-old or younger), a low education level, history of childhood violence, violence in the previous year, pregnancy, unintended pregnancy, and having 3 or more children. Being employed was a protective factor. Risk factors for women in CA included being older than19 years of age, being employed, history of childhood violence, and violence in the year prior to pregnancy. Risk factors for their partners as perpetrators included less than19 years of age for men in both countries and unemployment for men in CA. |

| Cunradi, C. (2009). Intimate partner violence among Hispanic men and women: The role of Drinking, neighborhood disorder, and acculturation-related factors. Violence and Victims, 24(1), 83–97. | (N = 2,547) A subsample of Hispanic men (N =1,148) and Hispanic women (N =1,399) from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse/Married, cohabitating adults ages 18 years and older. | Quantitative, cross-sectional secondary data analysis from the2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. The survey was administered via face to face interviews by bilingual field interviewers. Measures: Predictors-demographic data (age, household income, education level, employment status), drinking problems (DSM-IV), neighborhood disorder, acculturation Outcomes-IPV (hit or threatened to hit in past 12 months) |

Predictors of perpetration for men included less than a college education and neighborhood disorder. Predictors of perpetration for women included young age and low income. Predictors of victimization for men included being less than 35 years of age, less than a college education, full time employment, low income, and neighborhood disorder. Predictors of victimization for women included being less than 35 years of age, unemployment, past year of alcohol abuse, and neighborhood disorder. |

| Cunradi, C. B., Caetano, R., Clark, C., & Schafer, J. (2000). Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: A multilevel analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 10, 297–308. | (N = 527) Random probability sample of households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-SES (income, employment status, education), psychosocial variables (childhood violence victimization, approval of marital aggression, impulsivity), drinking (volume, ETOH-related problems), neighborhood-level variables (under-education, unemployment, working-class composition, and poverty), neighborhood poverty (1990 Census data defined by the “Federal poverty line”) Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Risk factors of MFPV included low income, male unemployment, increased female impulsivity, male/female alcohol problems, and approval of marital aggression. Protective factors included women being retired, older age, and being married. Predictors of FMPV were lower mean age, higher education, male impulsivity, and reported child abuse by both male and female. Retirement was associated with a decreased risk of IPV victimization for women. |

| Cunradi, C.B, Caetano, R., & Schafer, J. (2002). Socioeconomic predictors of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence, 17, 377–389. | (N = 527) Random probability sample of households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-sociodemographic characteristics; control measures including number of drinks per week, alcohol-related problems, parent-perpetrated violence during childhood, approval of marital aggression, impulsivity, marital status, number of children, cohabitating relationship length Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Risk factors for MFPV included a low annual household income, female alcohol consumption, female impulsivity, mean couple age, and female childhood victimization. Risk factors for FMPV included higher mean years of education (indicator of acculturation), female alcohol consumption, female childhood violence victimization, male impulsivity, and mean couple age. |

| Denham, A.C., Frasier, P.Y., Hooten, E.G., Belton, L., Newton, W., Gonzalez, P., Begum, M., & Campbell, M. K. (2007). Intimate partner violence among Latinas in Eastern North Carolina. Violence Against Women, 13, 123–140. | (N =1,212) Hispanic women working in 12 blue-collar work sites in the Health Works for Women/Health Works in the Community project in rural North Carolina. At least 18 years of age and the ability to speak English or Spanish. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, self-report, questionnaires in Spanish or English. Measures: Predictors-demographic data (age, race, ethnicity, marital status, education level, number of adults in the home, health insurance status, number of children), Level of Acculturation (Marin, Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, & Perez-Stable, 1987), length of stay in the U.S., health status (perceived health status, presence of chronic disease, height, weight, tobacco use, nutrition, exercise), presence of children in the home and lack of social support Outcomes-intimate partner violence (Abuse Assessment Screen; McFarlane, Parker, Soeken, & Bullock, 1992). |

Predictors for IPV among women who self-identified as being Hispanic included the presence of children in the home and lacking social support. |

| Duke, M.R., & Cunradi, C.B. (2011). Measuring intimate partner violence among male and female farmworkers in San Diego County, CA. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(1), 59–67. | (N = 100) San Diego County farmworkers (n = 61 female, n =37 male, 2 = unknown gender), mostly natives of Mexico (97%), married or cohabitating, 18 years and older, able to understand Spanish or English. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, surveys administered in Spanish through face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) staff. Measures: Predictors-personal background information (gender, age, education, place of birth, hours per week engaged in farm work), Migrant Farmworker Stress Inventory (Hovey, 2001), impulsivity (Caetano, Cunradi, Schafer, & Clark, 2000), Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) Outcomes-partner aggression and victimization-Physical Assault subscale of CTS2 (Strauset al., 1996). |

Past year victimization was 21.6% for men and 16.4% of women, but did not significantly differ by gender. High levels of stress were not significantly associated with IPV in past 12 months. However, “work conditions” were correlated with IPV perpetration in past year. Impulsivity did not differ by gender, but was significantly associated with past year IPV. Men had higher AUDIT scores and these were significantly associated with past year IPV. |

| Field, C.A., & Caetano, R. (2003). Longitudinal model predicting partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 27, 1451–1458. | (N = 387) Random probability sample of households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous United States. | Quantitative, longitudinal study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-childhood physical abuse, exposure to parental violence, impulsivity, approval of marital aggression, sociodemographic variables (ethnicity, age, and income), quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption, alcohol problems Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Risk factors for MFPV were male impulsivity and FMPV at baseline. The only risk factor for FMPV at follow-up was FMPV at baseline. |

| Fife, R.S., Ebersole, B. S., Bigatti, S., Lane, K.A., & Brunner Huber, L.R. (2008). Assessment of the relationship of demographic and social factors with intimate partner violence (IPV) among Latinas in Indianapolis. Journal of Women’s Health, 17, 769–775. | (N = 100) Hispanic women, 75.5% of Mexican-heritage with regular male partners in past 1–2 years, mean age 32.8 years, 8.6 mean years in U.S., and 71% married/domestic partner. | Quantitative, cross-sectional exploratory study. Used self-report questionnaires, bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) staff. Measures: Predictors-lifestyle (parent in household, respondent or partner drinks regularly), demographic characteristics Outcomes-physical, sexual, psychological, verbal & financial control in past 1–2 years assessed by Domestic Violence Network of Greater Indianapolis (2006) questionnaire about IPV |

Risk factors for IPV included being married, residing with partner, alcohol use by women or partner, and having a parent residing in the household. Only alcohol use (respondent or partner) remained significant controlling the other variables. |

| Garcia, L., Hurwitz, E.L., & Krauss, J. F. (2005). Acculturation and reported intimate partner violence among Latinas in Los Angeles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 569–590. | (N =464) Female participants self-identifying as Hispanic. The participants were recruited from 5public health care clinics in the Los Angeles area between August 1998 and December 2000. Women receiving gynecological or obstetric care were eligible for the study. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study. Data collected through face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-level of acculturation, presence of abuse, social support, Acculturation Rating Scale of Mexican Americans-II (Cuellar, Arnold, & Gonzalez, 1995), abuse measured using a scale developed by Castro, Garcia, Ruiz, and Peek-Asa (2006) Outcomes-reported abuse as measured by abuse scale (Castro, Garcia, Ruiz, & Peek-Asa, 2006) |

Women who were classified as highly acculturated reported the highest levels of IPV compared to individuals least acculturated to the U.S. |

| Glass, N., Perrin, N., Hanson, G., Mankowski, E., Bloom, T., & Campbell, J. (2009). Patterns of partners’ abusive behaviors as reported by Latina and non-Latina survivors. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(2), 156–170. | (N = 209) 55% Hispanic women; 75.4% Mexican. Mean age 34.6 years, 46.8% less than a high school education, 62.2% employed. 73% reported annual family income was $18,000 or less. Past year survivors of physical/sexual IPV. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the Women’s Health Survey collected through face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-Women’s Health Survey, which included demographic information and the IPV assessment Outcomes-patterns of abusive behavior (Danger Assessment Questionnaire; Campbell, 1995) |

Results showed that having a partner rated as an alcoholic/problem-drinker was a risk factor for IPV among Hispanic women. |

| Gonzalez-Guarda, R.M., Ortega, J., Vasquez, E.P. & DeSantis, J. (2010). La mancha negra: Substance abuse, violence and sexual risks among Hispanic males. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 32(1), 128–148. | (N =25) Hispanic, heterosexual, Spanish-Speaking men ages 18–55 years living in South Florida. | Qualitative study, 3 focus groups divided by language preference. Phenomena explored: Substance abuse, mental health, gender, education, acculturation, employment, negative experiences during childhood, financial stress, loneliness, relationship conflict |

Qualitative analysis using grounded theory yielded results of perceived risk factors for IPV including substance abuse, poor mental health, gender (female), lack of education, poor family upbringing, machismo/culture, immigration, gender roles, culture & acculturation, women’s employment, men’s unemployment negative experiences during childhood, financial stress, loneliness, and relationship conflict. |

| Gonzalez-Guarda, R.M., Peragallo, N., Urrutia, M.T., Vasquez, E.P., & Mitrani, V.B. (2008). HIV risks, substance abuse and intimate partner violence among Hispanic women and their intimate partners. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 19, 252–266. | (N = 82) Hispanic women 18–60 years of age with a history of IPV. Community dwelling women residing in S. Florida, U.S. born only. | Quantitative, Cross-sectional study, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers. Measures: Predictors-demographic data (age, number of years in the US, country of origin, and civil status; whether or not living with partner, number of children, religion and religiosity, education, employment, household income, individual income, insurance status), level of acculturation using the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (Marin & Gamba, 1996) Outcomes-sexual history (STIs, HIV, use of contraception) measured with the Sexual History Questionnaire (Peragallo, Gonzalez, & Vasquez, 2007), HIV risk, substance abuse, and IPV that occurred within the participants last 5 sexual relationships measured with the Partner Table (Peragallo, Gonzalez, & Vasquez, 2007), community violence and abuse during childhood measured with the Violence Assessment (Peragallo, Gonzalez, & Vasquez, 2007), substance abuse measured with the Partner Table (Peragallo, Gonzalez, & Vasquez, 2007), IPV (self-report physical or sexual abuse during current or most recent relationship on Violence Assessment Questionnaire, Peragallo, Gonzalez, & Vasquez, 2007) |

Participants who reported a history of IPV were more frequently under the influence of ETOH or drugs during sexual intercourse, were 6 times more likely to report a history of Sexually Transmitted Infections, were more likely to report having a partner who engaged in high-risk HIV activities (specifically, sex with commercial sex workers), and substance abuse. |

| Gonzalez-Guarda, R.M., Vasquez, E.P., Urrutia, M.T., Villarruel, A.M. & Peragallo, N. (2011). Hispanic women’s experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and risk for HIV. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 22(1), 46–54. | (N= 72) community-dwelling Hispanic women from South Florida, 18 years and older, 39.3 years mean age, average length of time in U.S. was 9.3 years, diverse country of origin, low mean monthly income of $493.05, 59.8% unemployed, 59.8% married, with the ability to understand English or Spanish. | Qualitative study, 8 focus groups. Phenomena explored: Level of acculturation, discrimination, gender inequalities, infidelity, age differences between partners, drug/alcohol abuse, ability to navigate the health system, self-esteem, history of victimization |

Three central themes emerged, “uprooted in another world, “the breeding ground for abuse,” and “breaking the silence.” Risk factors for IPV victimization included difficulty acculturating to the U. S., discrimination, machismo and gender inequalities, infidelity, family upbringing, age differences between partners, drug and alcohol abuse, difficulty navigating help services, poor self-esteem, and previous history of victimization. Risk factors for the perpetration of IPV included being a victim of abuse and observing violence at home and in the community. Protective factors included obtaining information, paying attention to oneself, healthy communication, decisions made to change the propagation of inequitable gender norms at home, and social support. |

| Jasinski, J.L., & Kaufman Kantor, G.K. (2001). Pregnancy, stress and wife assault: Ethnic differences in prevalence, severity, and onset in a national sample. Violence and Victims 16, 219–232. | (N = 846) Hispanics, sub-sample from 1992 National Alcohol and Family Violence Survey, Anglo and Hispanic pregnant and non-pregnant women of potential child-bearing age living with their male partner. All participants spoke English or Spanish. | Quantitative, secondary analysis from 1992 NAFV cross-sectional survey. Questionnaires were administered via telephone interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) assessors Measures: Predictors-ethnicity, poverty (income to needs ratio), educational attainment, life stressors (Social Readjustment Rating Scale; Holmes & Rahe, 1967). Outcomes-wife assault/and violence history (CTS; Straus, 1979, 1990). |

Pregnancy was associated with wife assault but this effect disappeared after controlling for poverty, age, and life stressors. Younger age was associated with an increased risk of wife assault. Stressful life events were associated with increased wife assault. |

| Lown, E.A., & Vega, W. A. (2001). Prevalence and predictors of physical partner abuse among Mexican American women. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 441–445. | (N = 1155) Subsample of Mexican-American women with current partners, ages 18–59 years, living in California. Participants had the ability to understand English or Spanish. | Quantitative, randomized household survey, one hour self-report interviews used CAPI system (computer administered personal interview) administered in the home of the participant by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) staff. Measures: Predictors-demographic information (birth place, etc.), income ratio, women’s heavy alcohol use, partner’s unemployment, social support (controlled for common risk factors of young age, greater number of children, poverty, urban residence, social isolation, and lack of church attendance) Outcomes-used Abuse Assessment Screen to assess physical abuse by current male (McFarlane et al., 1992) |

Risk factors for partner abuse included U.S. origin, residing in an urban environment, no church or infrequent church attendance, being younger than 30 years of age, lack of social support, and having 4 or more children in the home. |

| Martin, K.R., & Garcia, L. (2011). Unintended pregnancy and intimate partner violence before and during pregnancy in Latina women in Los Angeles, California. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 1157–1175. | (N =313) Hispanic pregnant women in the 3rd or 4th trimester who self-identified as being Latina and in a current heterosexual relationship. | Quantitative, secondary data analysis using data from a cross-sectional study conducted between 1998 and 2000 by researchers at The Southern California Injury Prevention Research Center at UCLA originally designed to assess the relationship between IPV and acculturation among Latina women. Measures: Predictors-pregnancy intent (Peek-Asa, Garcia, McArthur, & Castro, 2002) Outcomes-level of acculturation measured using the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-Americans II (ARSMA II; Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995), IPV during pregnancy and prior to pregnancy (screening instrument; Peek-Asa, et al., 2002). |

Women who reported physical or emotional abuse during pregnancy were more likely to be younger than 21 years of age, more educated, not married or not living with a current partner, more likely to have a partner younger than 21 years of age who was born in the US, and more likely to report having had more than one sexual partner. Predictors of IPV during pregnancy included IPV prior to pregnancy, unintended pregnancy, and higher acculturation, although no association was found in the multivariate model when age, education, and IPV before including pregnancy as a predictor variable of IPV. |

| Moreno, C. (2007). The relationship between culture, gender, structural factors, abuse, trauma, and HIV/AIDS for Latinas. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 340–352. | (N = 32) Latina women from two New York community-based agencies that deal with IPV and provide services for people with HIV/AIDS. | Qualitative, cross-sectional study that used focus groups, in-depth face-to-face narratives, and community meetings to collect data. Phenomena explored: History of child sexual abuse, presence of emotional deprivation, perceived threat of deportation, HIV status |

Themes: histories of trauma, living with HIV, vulnerability, and la suerte (fatalistic views of life). Perceived risk factors: history of child sexual abuse, emotional deprivation, threat of deportation, HIV + serostatus, cultural factors such as sexual submissiveness of women and infidelity of men, poverty, financial dependence on partner, and fatalistic belief of lives. The study concluded that the concept of marianismo may be a protective factor because it may be associated with sexual exclusiveness/may also be a risk factor as it prevents the woman from using condoms or inquire about partner’s sexual histories. Machismo may be protective as it emphasizes responsibility, but also a risk factor because it encourages multiple sex partners to demonstrate virility. |

| Moreno, C. L., Morrill, A.C., & El-Bassel, N. (2011). Sexual risk factors for HIV and violence among Puerto Rican women in New York City. Health & Social Work, 36(2), 87–97. | (N = 1003) Low-income Puerto Rican women recruited from local hospitals, living in the Bronx, NY. 50% U.S. born, age 18 to 73, 47% had high school education, 17% employed. Puerto-Rican women with the ability to understand English or Spanish. | Self-report through face-to-face interviews. Parent study was Project Connect (a 4-year longitudinal study).39% completed in Spanish. Measures: Predictors-sociodemographic variables including national origin, length of time in U.S., language preference (Spanish or English), age, relationship status, education, employment Outcomes-partner abuse as measured by the Physical Assault and Sexual Coercion Scale of CTS2 (Straus et al., 1996), sexual risk factors as measured by the Sexual Risk Behavior Questionnaire (Moreno et al., 2011) |

Higher risk of IPV was associated with being born in the U.S. and endorsing English as the language of preference for women in this study. |

| Santana, M.C., Raj, A., Decker, M.R., La Marche, A. & Silverman, J. (2006). Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence among adult men. Journal of Urban Health, 83, 575–585. | (N = 283) Convenience sample of heterosexual men, 74.9% Hispanic, who had sex with female partner in past 3 months recruited from urban community health center in Boston, ages 18 to 35 years. 37.5% unemployed, 15.2% married, 44.5% born in U.S. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data collected through written self-report surveys, 36.7% completed in Spanish. Measures: Predictors-demographic data, English fluency, length of time in U.S., masculine gender role ideologies as measured by the Male Role Attitudes Scale, (Pleck, Sonenstein & Ku, 1993) Outcomes-sexual risk behavior, CTS2 (Strauset al., 1996) |

Unprotected sex in past 3 months and MRAS scores were related to high rates of IPV perpetration. More traditional gender role ideologies were a risk factor for IPV perpetration and unprotected sex. |

| Schafer, J., Caetano, R., & Cunradi, C.B. (2004). A path model of risk factors for intimate partner violence among couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 127–142. | (N = 521) Random probability sample of households, 18+ years old, Hispanic married/cohabitating heterosexual couples in 48 contiguous U.S. | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, data from the National Alcohol Survey, face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual (Spanish and English speaking) interviewers Measures: Predictors-childhood physical abuse, ethnic identity, alcohol problems, impulsivity Outcomes-CTS Form R measurement of FMPV and MFPV (Straus, 1990) |

Female history of childhood physical abuse predicted FMPV and MFPV; male history of childhood physical abuse predicted MFPV. Female and male impulsivity as well as male alcohol problems predicted both MFPV and FMPV, whereas female alcohol problems predicted only MFPV. |

| Stampfel, C.C., Chapman, D.A., & Alvarez, A.E. (2010). Intimate partner violence and posttraumatic stress disorder among high-risk women: Does pregnancy matter? Violence Against Women, 16, 426–443. | (N = 655) 22% Hispanic women, 18+ years old, 48% unemployed, 55% high school education, 54% single. | Quantitative, quasi-experimental study, data from the Chicago Women’s Health Risk Study, data collected through in-person interviews. Measures: Predictors-demographic information, posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis, employment status, alcohol use, drug use, marital status, intimate partner relationship status and length, and health status Outcomes-three types of IPV including harassment (Sheridan, 1992), power and control (modified CTS), and physical violence (Johnson, 1996) |

Results of this study showed that Hispanic pregnant women were significantly less likely to experience IPV than non-pregnant women. |

Review of Published Research

Overview of studies

Of the 29 studies that were included, 9 examined both risk and protective factors for IPV victimization and/or perpetration, 17 examined only risk factors for IPV victimization and/or perpetration, and 3 studies (Aldarondo et al., 2002; Bell, Harford, Fuchs, McCarroll, & Schwartz, 2006; Santana, Raj, Decker, La Marche, & Silverman, 2006) exclusively examined the predictive variables associated with the perpetration of violence. Because identifying factors associated with IPV perpetration is critical to developing and improving programs aimed to prevent and reduce IPV, we included this small number of studies in our review. None of these studies exclusively examined protective factors for IPV. The vast majority of the studies included in this review explored etiological factors for IPV among women and men (n = 13), or women alone (n = 12). One study examined risk factors associated with male victimization (Gonzalez-Guarda, Ortega, Vasquez, & De Santis, 2010) and three studies focused exclusively on the characteristics of male perpetrators of IPV (Aldarondo et al., 2002; Bell et al., 2006, Santana et al., 2006).

Samples of Hispanics

The studies included in this review most frequently reported random probability sampling (n = 13) or convenience sampling (n = 15) for selecting participants, with one reporting stratified cluster sampling (Jasinski & Kaufman Kantor, 2001). Three studies that used convenience sampling also used snowball sampling (Gonzalez-Guarda, Peragallo, Urrutia, Vasquez, & Mitrani, 2008; Gonzalez-Guarda, Peragallo, Vasquez, Urrutia, & Mitrani, 2009; Gonzalez-Guarda, Vasquez, Urrutia, Villarruel, & Peragallo, 2011). The authors of the 13 research articles who employed random probability sampling methods included samples or sub-samples from large national research projects such as the 1992 National Alcohol and Family Violence Survey (Aldarondo et al., 2002; Jasinski & Kaufman Kantor, 2001), the 1995/2000 National Alcohol Survey (n = 10), the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (Cunradi, 2009), and the Mexican American Prevalence and Services Survey (Lown & Vega, 2001). Consequently, a great deal of the knowledge base regarding the etiology of IPV among Hispanics has been generated from these same samples. Few of the articles reviewed differentiated Hispanics according to subgroups. When subgroup information was provided, the information was included (see Table 1).

The majority of samples used in the studies included Hispanic women and/or their heterosexual male partners 18 years and older. Thirteen of the studies used national samples of individuals who self-identified as being Hispanic. In a study by Lown and Vega (2001), participants specifically identified themselves as being of Mexican origin. Of the remaining studies, researchers focused on Hispanics from one or two regions in the U.S. with the exception of Castro, Peek-Asa, Garcia, Ruiz, and Kraus (2003) who examined women from Morelos, Mexico and Los Angeles, California. Women came from other areas of the country such as Boston, California, Chicago, Indianapolis, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, and South Florida. Research conducted by Bell and colleagues (2006) was unique in that it examined men enlisted in the U.S. Army. Given the ethnic make-up of the areas examined throughout the country in these studies, samples were largely Mexican and Mexican-American. However, Moreno, Morrill, and El-Bassel (2011) specifically studied only Puerto Rican women in New York City. Most other studies did not further describe the different Hispanic ethnicities included in their studies other than stating individuals were self-identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Design

The most common research design included in this review was quantitative (n = 26) while three studies employed qualitative methods (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010, 2011; Moreno, 2007). Of the quantitative studies, 23 used a cross-sectional design with the remaining studies utilizing either longitudinal (Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2004; Field & Caetano, 2003) or quasi-experimental (Stampfel, Chapman, & Alvarez, 2010) designs. The most popular method of data collection was face-to-face interviews (n = 21), and was commonly utilized by the researchers in the National Alcohol Survey in 1995 and 2000 as well as others. Additional methods included using the Army Central Registry along with self-report surveys (Bell et al., 2006), self-report questionnaires (Denham et al., 2007; Fife, Ebersole, Bigatti, Lane, & Brunner, 2008; Santana et al., 2006), focus group transcripts (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010, 2011), phone interviews (Jasinski & Kaufman Kantor, 2001), or a combination of these methods (Moreno, 2007). All studies reported that bilingual assessors were used along with data collection in Spanish or the participant’s preferred language with the exception of one study that was a part of a larger state initiative (Stampfel et al., 2010). In the study by Stampfel and colleagues (2010), researchers utilized data previously collected in the Chicago Women’s Health Risk Study in which women were screened for IPV among entry to one of four medical care sites in Chicago and language for data collection was not specified.

Outcome measures

The main outcome variable of interest for this review is IPV. IPV is also commonly referred to as partner abuse, domestic violence, and partner assault. The most popular instrument used to determine the presence of IPV was the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1990) or the revised version (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Over half of the studies used this scale (n = 17) or one of the subscales. Outcome measures for each study can be found in Table 1.

Several studies used qualitative analysis to examine the etiology of partner abuse. For example, the three focus group studies (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010, 2011; Moreno, 2007) examined transcripts to identify major categories and themes describing participants’ experience with abuse. One advantage of using this method in contrast to strictly standardized questionnaires or interviews is that it allows for gathering of richer data and also allows participants to volunteer more information than they might otherwise be able to share. Nevertheless, because of the lack of use of measures in these studies etiological factors cannot be examined statistically.

Predictor measures

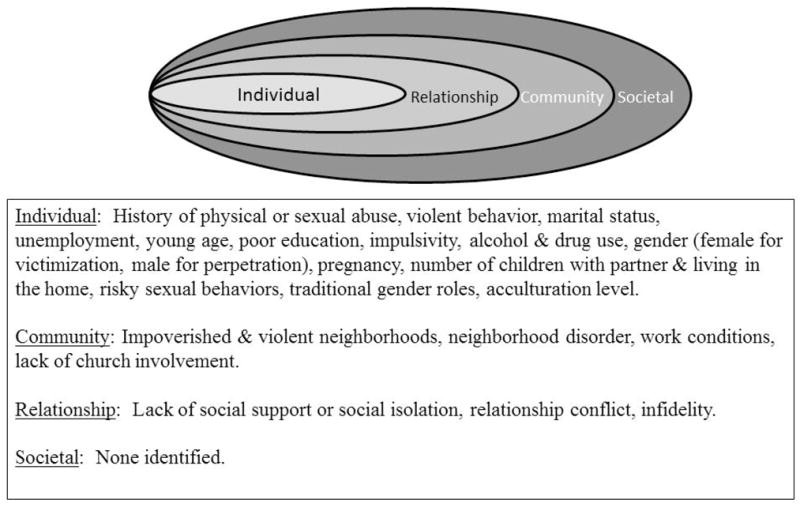

The articles identified risk/protective factors of IPV victimization and perpetration among Hispanics at the individual, relationship, community, and/or societal levels. The measures used to assess for these factors have been organized according to these subcategories. The specific measures and other factors assessed can be found in Table 1 for each study and a summary of overall risk factors identified at each level are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Risk factors for IPV identified according to the social-ecological model.

Results of the literature review organized into a visual representation of the four-level social-ecological model of violence prevention, adapted from Krug et al., 2002.

Analysis

Three of the articles (Gonzalez et al., 2010, 2011; Moreno, 2007) included qualitative analysis, all of whom used two or more independent coders to identify central themes. The remaining studies used statistics to describe the sample and find relationships between variables. The vast majority of these articles identified risk and protective factors for the perpetration and victimization of IPV through logistic regression (N = 20) and therefore examined their outcome as a binary variable (i.e., reported vs. did not report victimization or perpetration). In most cases, multiple hypothesized predictors were included in these regression models at one time. Two studies used chi-square analysis to compare proportions of participants reporting IPV to those who did not according to a number of variables (Caetano, Schafer, & Cunradi, 2001; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008). Two studies conducted a path analysis of predictors to identify direct and indirect (i.e., mediators) relationships between hypothesized variables and female-to-male violence (FMPV) and male-to-female violence (MFPV; Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Harris, 2010; Schafer, Caetano, & Cunradi, 2004). Social control and social cohesion were evaluated as potential mediators between neighborhood poverty and IPV (Caetano et al., 2010). Impulsivity and alcohol were evaluated as potential mediators between child abuse and IPV (Schafer 2004). The remaining studies used Pearson’s correlations between hypothesized risk factors and IPV in pregnant women (Castro et al., 2003) and hierarchical cluster analysis to identify typologies of IPV abusers (Glass et al., 2009).

The ten studies based on the National Alcohol Survey conducted separate analysis for FMPV and MFPV. Although all but one of the studies reported in this review conducted analysis according to Hispanic ethnicity, as this was one of the criteria for inclusion, there was only one study that examined relationships according to Hispanic country of origin, and therefore, analyses did not make such distinction. Even though the study conducted by Santana et al. (2006) did not analyze the data by ethnicity, the majority of the sample identified as Hispanic (74.5%) and so it was included in this review. Age, acculturation, and socioeconomic factors were common control measures included in the analyses across studies.

Results

Overall, men and women shared many similar risk factors for both perpetration and victimization of IPV. However, some articles included in this review produced conflicting results and these will be discussed further where appropriate. It is important to note that given the nature of reviewing studies in which data collected was through self-report, more information was available related to individual level factors than the other levels. Table 1 describes the risk and protective factors associated with IPV found in each article. Figure 1 includes the factors that have been consistently identified as being associated to IPV among Hispanics according to the four levels of the social-ecological model (CDC, 2009; Krug et al., 2002).

Individual

Several factors were consistently shown to be risk factors for abuse. For example, a history of physical and/or sexual abuse, especially in childhood, was shown to be a risk factor for both victimization and perpetration among men and women (Caetano, Schafer, Clark, Cunradi, & Raspberry, 2000; Castro et al., 2003; Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 2000; Cunradi et al., 2002; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010; Moreno, 2007; Schafer et al., 2004). A history of experiencing violence or exhibiting violent behavior is suggested to predict future violent behavior, which is consistent with what is known about the cycle of violence being passed down by generations in families (Aldarondo et al., 2002; Field & Caetano, 2003; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008, 2010, 2011). Additionally, unemployment, young age, marital status, low levels of education, impulsivity, and alcohol or drug abuse were factors consistently related to the perpetration and victimization of violence in the relationships examined in these studies (Aldarondo et al., 2002; Bell et al., 2006; Caetano, Cunradi, Clark, & Schafer, 2000; Caetano, Nelson, & Cunradi, 2001; Caetano et al., 2004; Caetano, Schafer, et al., 2000; Caetano, Schafer et al., 2001; Castro et al., 2003; Cunradi, 2009; Cunradi et al., 2000; Cunradi, 2002; Duke & Cunradi, 2011; Field & Caetano, 2003; Fife et al., 2008; Glass et al., 2009; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008, 2010, 2011; Jasinski & Kaufman Kantor, 2001; Lown & Vega, 2001; Martin & Garcia, 2011; Moreno, 2007; Schafer et al., 2004). Female gender was found to be a risk factor for victimization (Field & Caetano, 2003; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010). Women who reported being financially dependent on their partner were found to have higher risk of victimization (Moreno, 2007). Low self-esteem was also associated with victimization among women (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2011).

Studies including pregnant women yielded conflicting results about whether pregnancy was shown to be a risk or protective factor (Castro et al., 2003; Denham et al., 2007; Jasinski & Kaufman Kantor, 2001; Martin & Garcia, 2011; Stampfel et al., 2010). Whether or not the pregnancy is planned may impact the likelihood of IPV, and one study found that unintended pregnancy was related to increased violence (Martin & Garcia, 2011). Also, partner violence prior to pregnancy was often associated with violence occurring and/or increasing during pregnancy (Jasinski & Kaufman Kantor, 2001; Martin & Garcia, 2011). Number of children, such as having four or more with current partner, and having children living in the home were also associated with an increased risk for IPV victimization (Castro et al., 2003; Denham et al., 2007; Lown & Vega, 2001). Several studies examined more broadly sex practices of their research participants as it relates to risk for IPV victimization (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008; Moreno, 2007; Santana et al., 2006). However, it is difficult to know the direction of effects for risk factors related to sexual risky behaviors and IPV. For example, positive HIV serostatus and female sexual submissiveness were found to be highly associated with IPV (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008; Moreno, 2007). Other risky behaviors such as having numerous sex partners and inconsistent condom use were also related to partner violence (Martin & Garcia, 2011; Moreno, 2007; Santana et al., 2006).

The review revealed conflicting evidence related to cultural factors. Some studies documented how cultural factors were protective, while others documented risk associated with cultural attributes. For example, several studies found that adhering to traditional gender roles and embracing concepts such as marianismo and machismo were related to an increase in the risk of violence in the relationship (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010, 2011), yet another study found them to be protective factors (Moreno, 2007). Marianismo is a term used to define the woman’s role in traditional Latin American culture in which they are expected to be submissive, modest, and responsible for the caretaking of children. Machismo is the alpha male stereotype in Latin culture and encompasses such qualities as virility, bravado, and responsibility as the decision-maker of the family. In the context of IPV, machismo may be a risk factor when associated with desire for power and control in the relationship, but may also protect female partners from experiencing violence when associated with the positive aspects of this construct such as responsibility and respect for family (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2011; Moreno, 2007). Other cultural factors that produced conflicting results include country of origin and acculturation level (Aldarondo et al., 2002; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010, 2011; Lown & Vega, 2001; Martin & Garcia, 2011; Moreno et al., 2011). Some studies found that Hispanics born in the U.S. and those who reported being more highly acculturated had higher rates of IPV (Caetano, Schafer, et al., 2000; Garcia, Hurwitz, & Krauss, 2005; Lown & Vega, 2001; Martin & Garcia, 2011; Moreno et al., 2011).

A few of the studies focused on identifying protective factors associated with IPV prevention. Of these studies, factors that were consistently found to be associated with protection from IPV included older age, being employed, higher income, being retired, and individuals classified as having high-medium levels of acculturation (Caetano, Cunradi, et al., 2000; Caetano, Nelson, et al., 2010; Caetano et al., 2004; Caetano, Schafer, et al., 2000; Castro et al., 2003; Cunradi et al., 2000). Women who reported being married to their partner also were found to be more protected from experiencing IPV than those who were unmarried (Caetano, Cunradi, et al., 2000; Caetano, Schafer, et al., 2000). However, protective factors were less often included in comparison to the extent that risk factors were and so less information is available about characteristics of individuals that may protect against violence.

Relationship

Lack of social support or social isolation was one relationship factor commonly found to be associated with experiencing IPV (Denham et al., 2007; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2010; Lown & Vega, 2001). This is consistent with what we know about the cycle of violence in which the abusive partner often aims to isolate the victim from his or her family and friends, making it difficult to leave the relationship. On the other hand, social support and healthy communication were found to be a protective factor (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2011). Relationship conflict and infidelity in the intimate relationship were also found to be risk factors for IPV (Gonzalez-Guarda, 2010, 2011).

Community

Participants experiencing poverty or residing in impoverished and violent neighborhoods were more likely to report violence in the relationship (Caetano et al., 2010; Caetano, Schafer, et al., 2001; Cunradi, 2009; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2011). Living in an urban area was also found to be related to higher risk of experiencing IPV (Lown & Vega, 2001), as well as living where there is perceived neighborhood disorder (Cunradi, 2009). Neighborhood disorder was measured by asking participants to report on their level of agreement regarding the extent to which violence, drug use, abandoned buildings and graffiti were present in their neighborhood. Negative work conditions were also found to be strongly and positively correlated with IPV among migrant farmworkers in California (Duke & Cunradi, 2011). These conditions were measured by a subscale of a stress assessment for migrant farmworkers that contained three questions regarding whether the farmworker was able to drink enough water during work, was being taken advantage of in work, or experienced discrimination. Finally, individuals who reported little or no church attendance were more likely to report IPV (Lown & Vega, 2001).

Societal

Information on societal level factors such as policies, legal sanctions, and social norms were not analyzed in any of the studies included in this review. It is important to note the lack of findings may be due the nature of research articles included in this review.

Discussion

Research

An extensive review of the literature utilizing a social-ecological framework yielded 29 studies that described risk and/or protective factors for IPV among Hispanics. Although these studies have contributed significantly to the current state of knowledge regarding the etiology of IPV among Hispanics, there are many gaps in the research literature that need to be filled. For example, no risk or protective factors were found in these studies at the societal level. Interestingly, as seen in Figure 1, the size of the ovals representing levels in the social-ecological model are inversely related to the number of risk and protective factors reported at each respective level. More research is needed at the relationship, community, and societal levels as well as the ways in which these may interact with each other. Additionally, the majority of the studies reviewed primarily focused on risk factors for IPV. Although this knowledge base is necessary for the development of risk reduction strategies, there is also a need to understand the factors that are present in the Hispanic culture that can protect individuals and families from experiencing and perpetrating IPV. This information is fundamental for the development of prevention strategies that do not perpetuate stereotypes regarding IPV among Hispanics (e.g., Hispanic men are machista-male chauvinist), but rather builds upon the strengths that are pervasive in the Hispanic culture (e.g., strong family ties, respect for mothers). Furthermore, there only appears to have been two studies in the past 2 years describing the factors associated with the perpetration of IPV among Hispanics (Aldarondo et al., 2002; Bell et al., 2006). This knowledge base is instrumental to identifying individuals at risk and developing strategies that serve as a buffer to what otherwise may lead to a violent trajectory.

Research that looks at intra-ethnic variations among Hispanics is urgently needed. In the past 10 years there has not been one single study that has explored differences in risk or protective factors associated with IPV across Hispanic country of origin. In fact, Kaufman Kantor, Jasinki, and Aldarondo (1994) have been the only known investigators to have explored these differences. Their findings suggest that there are dramatic differences in IPV among Hispanics from different countries of origin. More research regarding differences by country of origin as well as common and unique predictors of IPV is needed to inform culturally specific intervention and prevention strategies targeting Hispanics. It is necessary for researchers to use valid and reliable measures to accurately capture the phenomena of IPV and factors that may be predictors; however, more research is needed to examine the cultural appropriateness of these measures for use in Hispanic populations.

Practice

There are some general factors that appear to place Hispanics at risk for both the victimization and perpetration of IPV. These include un-modifiable demographic factors at the individual level such as young age, as well as socioeconomic disadvantages such as unemployment and low income, which could be modified. Consequently, when health and social service providers interact with individuals involved in IPV situations, one of their primary aims should be to modify socioeconomic circumstances that may have contributed to either the perpetration or victimization of IPV as well as to why victims choose to remain in abusive relationship. Without addressing these underlying circumstances, other interventions (e.g., psychotherapy) may not be successful. Additionally, because young age is such an important predictor of IPV, culturally appropriate prevention strategies that address IPV among Hispanic youth are needed. While these strategies need to draw upon successful violence prevention strategies that have been used with other type of youth, they must also contain approaches to address the unique needs and preferences of Hispanic youth and their families. Finally, IPV appears to highly correlate with other behavioral risk factors such as alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors, yet more research is needed to better understand the relationship between these factors. It is recommended that health and social service providers assess and address other behavioral risk factors when working with victims and perpetrators of IPV. It appears that in order for prevention efforts targeting IPV to be effective, they must also include strategies to prevent other risky behaviors such as alcohol abuse. Developing prevention models which integrate a multi-level approach to violence would be most effective in the prevention of IPV.

Policy

Despite the lack of findings at the societal level, there are a number of policy recommendations that need to be implemented in order to adequately address and prevent IPV among Hispanics. As noted previously, socioeconomic disadvantages are highly correlated with IPV. Nevertheless, some Hispanics do not qualify for the social services provided to other victims of IPV because of documentation status. If laws have been created to protect undocumented immigrants from being deported as a victim of IPV, then the eligibility criteria for programs supporting the social-economic well-being of victims will need to be changed to also provide support to victims regardless of immigration status. Although some may argue that the government and tax-payers should not fund programs that support non-citizens, the provision of services to victims of IPV who are not documented may be an effective approach to preventing repeated IPV victimization and the associated negative physical, psychological, and social health consequences. Other policy level interventions that increase access to employment opportunities and healthy work and neighborhood environments may also contribute to the prevention of IPV among Hispanics, despite their immigration status. Nevertheless, policies surrounding IPV need to be evaluated empirically to assess their cost-effectiveness.

Contributor Information

Amanda M. Cummings, School of Education, University of Miami School of Education

Rosa M. Gonzalez-Guarda, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami

Melanie F. Sandoval, School of Nursing, University of Virginia

References

- Aldarondo E, Castro-Fernandez M. Risk and protective factors for domestic violence perpetration. In: White JW, Koss MP, Kazdin AE, editors. Violence against women and children, Volume 1: Mapping the terrain. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Aldarondo E, Kaufman Kantor G, Jasinski JL. A risk marker analysis of wife assault in Latino families. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:429–454. doi: 10.1177/107780120200800403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azziz-Baumgartner E, McKeown L, Melvin P, Dang Q, Reed J. Rates of femicide in women of different races, ethnicities, and places of birth: Massachusetts, 1993–2007. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:1077–1090. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care. 2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. AUDIT. Retrieved from http://www.unicri.it/min.san.bollettino/dati/auditbro.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bell NS, Harford TC, Fuchs CH, McCarroll JE, Schwartz CE. Spouse abuse and alcohol problems among White, African American, and Hispanic U.S. Army soldiers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1721–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Cannon EA, Slesnick N, Rodriguez MA. Intimate partner violence in Latina and non-Latina women. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2009;36(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. Acculturation and drinking patterns among U.S. Hispanics. British Journal of Addiction. 1987;82:789–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Clark CL, Schafer J. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among White, Black and Hispanic couples. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11(2):123–138. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field CA, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. The 5-year course of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic Couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:1039–1057. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Nelson S, Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence, dependence symptoms and social consequences from drinking among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. American Journal on Addictions. 2001;10:S60–S69. doi: 10.1080/10550490150504146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Harris R. Neighborhood characteristics as predictors of male to female and female to male partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1986–2009. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. Acculturation, drinking, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the United States: A longitudinal study. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(1):60–78. doi: 10.1177/0739986303261812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Clark CL, Cunradi CB, Raspberry K. Intimate partner violence, acculturation, and alcohol consumption among Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:30–45. doi: 10.1177/088626000015001003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Cunradi CB. Alcohol-related intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic Couples in the United States. Alcohol Research & Health. 2001;25(1):58–65. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh25-1/58-65.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D, Roizen R, Room R. Alcohol problems and their prevention: Public attitudes in California. In: Room R, Sheffield S, editors. The prevention of alcohol problems: Report of a conference. Sacramento, CA: California State Office of Alcoholism; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Prediction of homicide of and by battered women. In: Campbell JC, Milner J, editors. Assessing dangerousness: Potential for further violence of sexual offenders, batterers, and child abusers. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Castro R, Garcia L, Ruiz A, Peek-Asa C. Developing an index to measure violence against women for comparative studies between Mexico and the United States. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-9005-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro R, Peek-Asa C, Garcia L, Ruiz A, Kraus JF. Risks for abuse against pregnant Hispanic women Morelos, Mexico and Los Angeles County, California. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:325–332. doi: 10.1016/S07493797(03) 00211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intimate partner violence. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding intimate partner violence: Fact sheet. 2011 Retrived from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/IPV_factsheet-a.pdf.

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. doi: 10.1177/07399863950173001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence among Hispanic men and women: The role of drinking, neighborhood disorder, and acculturation-related factors. Violence and Victims. 2009;24(1):83–97. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark C, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: A multilevel analysis. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Socioeconomic predictors of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17:377–389. doi: 10.1023/A:1020374617328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denham AC, Frasier PY, Hooten EG, Belton L, Newton W, Gonzalez P, Campbell MK. Intimate partner violence among Latinas in Eastern North Carolina. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:123–140. doi: 10.1177/1077801206296983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]