Abstract

Background

The Centor and McIsaac scores guide testing and treatment for group A streptococcal (GAS) pharyngitis in patients presenting with a sore throat, but were derived on relatively small samples. We perform a national-scale validation of the prediction models on a large, geographically diverse population.

Methods

Analysis of data collected from 206,870 patients 3 years and above who presented with a painful throat to a United States national retail health chain, from September 2006-December 2008. Main outcome meaures were the proportions of patients testing positive for GAS pharyngitis according to Centor and McIsaac scores (both scales 0-4).

Results

For patients 15 years and older, 23% (95% confidence interval (CI) 22%-23%) tested GAS positive including 7% (7-8%) of those with a Centor score of 0, 12% (11-12%) with 1, 21% (21-22%) with 2, 38% (38-39%) with 3, and 57% (56-58%) with 4. For patients 3 years and older, 27% (95% CI 27-27%) tested GAS positive with 8% (8-9%) of those testing positive with McIsaac score 0, 14% (13-14%) with 1, 23% (23-23%) with 2, 37% (37-37%) with 3, and 55% (55-56%) with 4. 95% CI’s overlapped between the MinuteClinic derived probabilities and the prior reports.

Conclusion

Our study validates the Centor and McIsaac scores and more precisely classifies risk of GAS infection among patients presenting with a painful throat to a retail health chain.

Introduction

Group A streptococcal (GAS) pharyngitis is the most common cause of bacterial pharyngitis affecting over a half-billion people annually worldwide.1 GAS pharyngitis is both the antecedent for invasive streptococcal infections such as necrotizing fasciitis and the post-infectious immunologic complication of rheumatic fever/rheumatic heart disease, a leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in many developing parts of the world. Physical examination of the posterior oropharynx is an inaccurate method to distinguish GAS from other causes of acute pharyngitis2, so the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine (ACP-ASIM), endorse applying the four point Centor clinical scoring scale to classify risk of GAS and guide management of acute pharyngitis in adults (Table 1.)3, 4 Developed three decades ago based on evaluation of 286 adults at a single emergency department, the Centor score helps clinicians distinguish GAS from viral pharyngitis, and thereby appropriately prescribe antibiotics to alleviate symptoms and decrease the rates of acute rheumatic fever, suppurative complications, missed school and work days, and disease transmission.5 The McIsaac score, derived from 521 patients from a University-affiliated family practice in Toronto and validated on 621 patients from 49 Ontario communities, adjusts the Centor score based on the patient’s age.6, 7 Since younger patients are more likely to have GAS than older patients, the McIsaac score is calculated by adding one point to the Centor score for patients ages 3-14 years, and subtracting one point for those age 45 years and above. Because clinical prediction models may perform poorly when applied to new settings, it is important to validate them on different populations and over time.8, 9 Further, despite endorsement from CDC and ACP-ASIM, the clinical scores have gained poor traction in clinical practice,10 perhaps in part due to the perception that the scores were derived from a relatively small sample. Here we analyzed a geographically diverse population of patients who presented with sore throat to MinuteClinic, a large retail health chain, to perform the largest validation studies of the Centor and McIsaac scores.

Table 1. American College of Physicians/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for the Management of Pharyngitis.

| Centor score | American College of Physicians/ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines |

|---|---|

| 0 | Do not test, Do not treat |

| 1 | Do not test, Do not treat |

| 2 | Treat if rapid test positive |

| 3 | ACP/CDC option 1: Treat if rapid test positive, or ACP/CDC option 2: Treat empirically |

| 4 | Treat empirically |

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advocate the American College of Physicians guideline based on the Centor score for management of acute pharyngitis in adults.3 To calculate the Centor score, patients receive one point for each of the following: fever, absence of cough, presence of tonsillar exudates, and swollen, tender anterior cervical nodes. Based on these signs and symptoms, the Centor score is calculated (0-4). The McIsaac score adjusts the Centor score to account for the increased incidence of GAS in children and decreased incidence in older adults, by adding one point to the Centor score for those under age 15 years and subtracting one point for those age 45 years and older.

Methods

Study Design

We analyzed retrospective data collected from patients tested for GAS pharyngitis when they presented with a painful throat from September 1, 2006 to December 1, 2008 to MinuteClinic, a large, national retail health chain with over 500 sites in 26 states.11-14 From the retail clinic’s 581 sites, the dataset included 238,656 patient encounters across 25 states. In this setting, physician assistants or nurse practitioners collect standardized historical and physical exam information based on algorithm-driven care. The clinicians enter these codified data in real-time, and the information is stored in a common database across all clinic locations. MinuteClinic providers have demonstrated greater than 99% adherence to an established acute pharyngitis protocol, the “Strep Pharyngitis Algorithm” from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement.15, 16 According to this algorithm, medical providers collect structured information about patients’ relevant signs and symptoms, obtain rapid antigen testing on all patients with pharyngitis (with confirmatory testing used for patients whose rapid test is negative), and treat only those patients with a positive test for GAS. The dataset included only patient visits where there was complete information about age, all signs and symptoms included in the Centor and McIsaac scores, and test results.

We included patient-visits if a patient presented with a chief complaint of painful throat and was tested for GAS pharyngitis, or if a patient had symptoms of pharyngitis and was tested for GAS pharyngitis. Patient-visits were excluded if the patient reported having been treated for GAS within the one month prior to the visit. Patients under three years old were excluded since neither the Centor nor McIsaac rule is intended for use in those patients. For patients with multiple visits during the study period, we included the first visit only. Patients were not excluded if they were pregnant or had co-morbid conditions. MinuteClinic practice is to not care for patients with septic appearance but to refer them to emergency department care.

Test methods

All MinuteClinic locations used the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-waived Quick Vue In-Line Strep A test (Quidel Corp., San Diego, California). The confirmatory test was a streptococcal DNA probe (74%) or throat culture (26%). Patients were categorized as GAS positive if either test (rapid or confirmatory) was positive.

Statistical Analysis

Predictor variables and covariates were developed for age, sex, history of fever in previous 24 hours, history of exposure to someone with GAS pharyngitis, presence of cough, duration of pharyngitis symptoms (days), presence of erythematous tonsils, presence of tonsillar exudates, presence of swollen tonsils, presence of swollen anterior cervical lymph nodes, presence of swollen posterior cervical lymph nodes, and presence of rhinorrhea. Streptococcal test results were extracted for each patient.

All patients fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to validate the McIsaac score and all patients age 15 years and older were used to validate the Centor score. The Centor score was calculated by summing the following clinical factors: history of fever, presence of tonsillar exudates, presence of swollen anterior cervical lymph nodes, and absence of cough. The McIsaac score was calculated for all patients aged three years and older by adding one point to the Centor score for those under age 15 years and subtracting one point from the Centor score for those aged 45 years and older.17 McIsaac scores of −1 and 5 were normalized to 0 and 4.7

Two approaches were taken to validate the scores. First, we compared the likelihood of GAS pharyngitis by clinical score in the MinuteClinic patients to the likelihood of GAS pharyngitis by clinical score in the published data. Second, we applied logistic regression to the MinuteClinic data to derive new prediction models, maintaining the same parameter that they be limited to no more than four clinical variables. The four chosen variables derived from the cohort of patients aged 15 years and older were then compared with the four variables that comprise the Centor score.

Calculation of GAS probabilities

The percent of patients aged 15 years and above in the retail health data who tested GAS positive by Centor score (0-4) was calculated and compared with the original Centor report4 and the Wigton validation study18. The percent of patients aged 3 years and older in the retail health data who tested GAS positive by McIsaac (0-4) was calculated and compared with the McIsaac studies.6, 7 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the proportion of patients testing positive at each score. The 95% confidence intervals around the proportion testing positive by score in the retail health data were compared with the 95% confidence intervals in the Centor and McIsaac studies.

Selection of variables

Variables included in the Centor and McIsaac scores as well as variables not included in the scores were examined to determine the best predictors of GAS pharyngitis among the MinuteClinic patients. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify predictors of GAS pharyngitis. Significance of association of categorical variables with GAS pharyngitis was tested by Chi-square. In the multivariate analysis, candidate predictors were entered into a stepwise logistic regression to identify independent predictors of patients with GAS pharyngitis. P value cutoffs for entry and departure for the multivariate regression models were 0.25 and 0.10, respectively. For the purpose of simplicity and usability and to facilitate comparison with the prior studies, the final model was limited to four predictor variables and assessed by area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AUC).

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro software, version 9.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

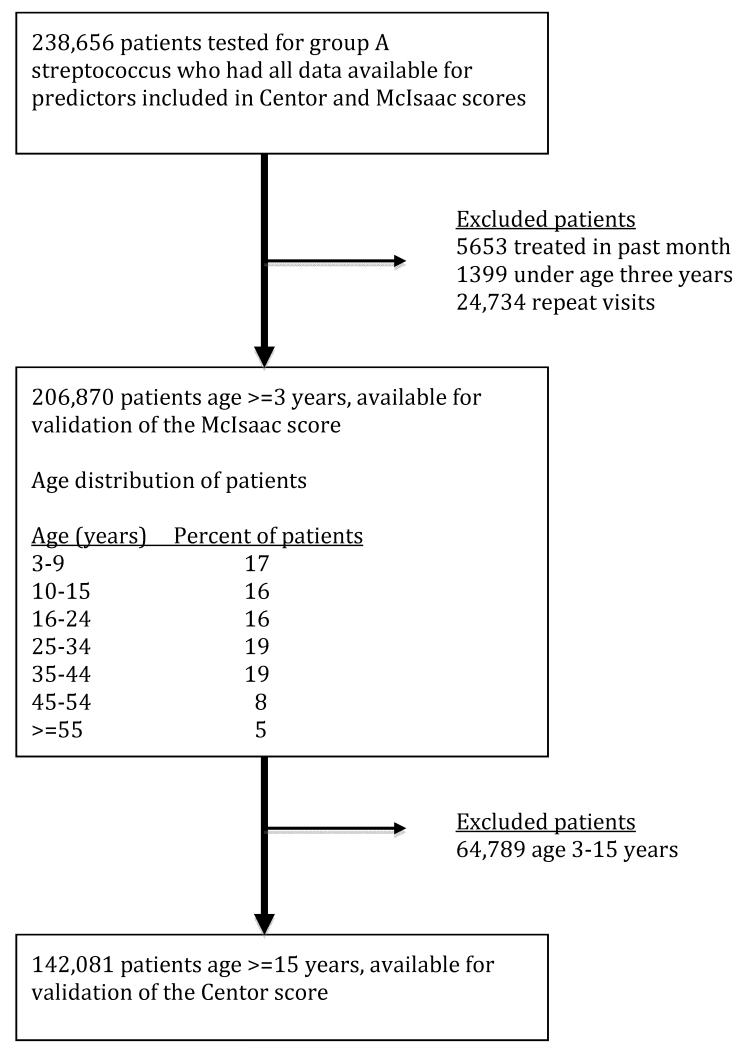

Of 238,656 patient-visits, 5653 were excluded due to treatment for GAS within the prior month and an additional 1399 were excluded because the patient age was under three years old, leaving 231,604 patient-visits. For patients with multiple visits only the first visit was included, leaving 206,870 patients to validate the McIsaac score. Of these, 64,789 (31%) visits occurred in patients under age 15 years, leaving 142,081 visits for the validation of the Centor score (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Patient flow diagram.

Validation of the Centor score

Among the 142,081 retail health visits for patients age 15 years and older, 23% (95% confidence interval 22-23%) tested positive for GAS, compared to 17% (14-23%) in the original Centor paper and 26% (24-32%) in the validation study of the Centor score. Two-thirds of the patients in the retail health dataset were female, and the average age was 34 years. Table 2 displays the characteristics of the study population for age, sex and clinical signs and symptoms of pharyngitis by GAS result for those aged 3 years and older and for those aged 15 years and older. In both groups, patients who tested positive for GAS pharyngitis were more likely to present with tonsillar exudates, swollen anterior cervical lymph nodes, tonsillar swelling, history of fever in the previous 24 hours, absence of cough, lack of rhinorrhea, swollen posterior cervical lymph nodes, exposure to GAS, and temperature above 101 degrees Fahrenheit at the time of presentation.

Table 2. Characteristics of the 206, 870 retail health patients with pharyngitis*.

| Characteristics | Age>=3 years n=206,870 |

Age >=15 years n=142,081 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAS Positive (n=56,013) |

GAS negative (n=150,857) |

GAS Positive (n=32,054) |

GAS negative (n=110,027) |

|

| Mean Age, (median [IQR]), years |

23 (20 [9-35]) | 28 (26 [14-39])** | 33 (33 [24-40]) | 34 (33 [24-42])** |

| Male sex n (%) | 22,768 (41) | 54,540 (36)** | 10,916 (34) | 36,073 (33)** |

| Fever n (%) | 30,710 (55) | 52,006 (34)** | 15,482 (48) | 33,110 (30)** |

| Absence of cough n (%) | 40,538 (72) | 93,255 (62)** | 23,251 (73) | 67,651 (61)** |

| Anterior Cervical Lymphadenopathy n (%) |

42,662 (76) | 83,249 (55)** | 24,765 (77) | 59,910 (54)** |

| Tonsillar exudate n(%) | 21,963 (39) | 24,513 (16)** | 14,478 (45) | 18,922 (17)** |

| Tonsillar swelling n (%) | 34,525 (62) | 54,528 (36)** | 18,248 (57) | 34,827 (32)** |

| Temp > = 101 F n (%) | 3455 (6) | 4213 (3)** | 1183 (4) | 1934 (2)** |

| Exposure to GAS n (%) | 19,718 (35) | 38,429 (25)** | 10,739 (34) | 26,316 (24)** |

| Lack of rhinorrhea n (%) | 44,473 (79) | 110,666 (73)** | 25,899 (81) | 80,860 (73)** |

| Posterior Cervical Lymphadenopathy n (%) |

5044 (9) | 8651 (6)** | 2876 (9) | 6094 (6)** |

| Symptom duration | ||||

| <24 hours n (%) | 10,557 (20) | 23,449 (17)** | 4199 (13) | 13,469 (13)** |

| 1-2 days n (%) | 25,928 (46) | 56,172 (38)** | 14,098 (44) | 38,132 (36)** |

| 3-4 days n (%) | 14,436 (26) | 43,138 (29)** | 9881 (31) | 33,791 (32)** |

| >= 5 days n (%) | 5092 (9) | 23,563 (16)** | 3876 (12) | 20,364 (19)** |

IQR - interquartile range

Data presented as Number (percentage) unless otherwise specified

p<0.001 (positive vs negative)

Table 3 displays the percent of patients testing positive for GAS by clinical score in the retail health data, compared to the published literature by Centor et al4, Wigton et al18, and McIsaac et al.6, 7 Patients in the retail health population had GAS positivity rates in an intermediate range between the Centor and Wigton reports, and were more likely to have GAS pharyngitis than patients in the McIsaac study. The 95% confidence intervals around the percent of patients testing positive in the retail health cohort overlapped with the 95% confidence intervals around the percent testing positive by score in the Centor and Wigton studies. Table 4 shows the risk of GAS pharyngitis according to the number of predictors present, stratified by the ages used in the McIsaac classification. In the multivariate logistic regression model, the same four candidate predictors were selected from the retail health data, as in the original Centor report. Presence of tonsillar exudates conferred the highest odds of having strep infection (3.1, 95% confidence interval 3.0-3.2) followed by swollen anterior cervical lymph nodes (2.2, 2.1-2.3), history of fever (1.7, 1.7-1.8) and absence of cough (1.6, 1.5-1.6).

Table 3.

Percent of patients testing GAS positive by Clinical Score in National Retail Health Data Compared to Published Data

| Score | Retail Health Data (ages >=15 years) n=142,081 % [95%CI] |

Centor (1981) (Derivation study) n=286 % [95%CI] |

Wigton (1996) (Validation study) n=516 % [95%CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centor 0 n=13,603 |

7 (7-8) | 3 (0-16) | 3 (0-14) |

| Centor 1 n=45,080 |

12 (11-12) | 7 (2-14) | 14 (9-21) |

| Centor 2 n=47,167 |

21 (21-22) | 16 (8-27) | 23 (17-30) |

| Centor 3 n=26,769 |

38 (38-39) | 34 (20-46) | 45 (36-54) |

| Centor 4 n=9462 |

57 (56-58) | 56 (35-77) | 54 (42-67) |

| Overall | 23 (22-23) | 17 (14-23) | 26 (24-32) |

|

Retail Health Data

(ages >=3 years) n=206,870 % [95%CI] |

McIsaac (1998)

(Derivation study) n=521 % [95%CI] |

McIsaac (2000)

(Validation study) n=619 % [95%CI] |

|

| McIsaac 0 n=23,339 |

8 (8-9) | 3 (1-6) | 1 (0-4) |

| McIsaac 1 n=47,083 |

14 (13-14) | 5 (2-10) | 10 (6-16) |

| McIsaac 2 n=59,130 |

23 (23-23) | 11 (6-19) | 17 (11-25) |

| McIsaac 3 n=47,234 |

37 (37-37) | 28 (18-41) | 35 (25-45) |

| McIsaac 4 n=30,084 |

55 (55-56) | 53 (40-66) | 51 (40-62) |

| Overall | 27 (27-27) | 14 (11-17) | 17 (14-20) |

Table 4.

Risk of GAS Pharyngitis by Age Group for Retail Health Clinic Patients with 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 Clinical Predictors, n = 206,870

| Number GAS positive/Total (% GAS positive) by Age Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Clinical Predictors Present |

3-14 years old n=64,789 |

15-44 years old n=114,803 |

>=45 years old n=27,278 |

| 0 Predictors (# positive/ total) (% positive, 95% CI) |

670/4009 (17, 16-18)) |

745/9778 (8, 7-8)) |

258/3825 (7, 6-8)) |

| 1 Predictor | 3816/16,683 (23, 22-24)) |

4218/34,381 (12, 12-13) |

1031/10,699 (10, 9-10)) |

| 2 Predictors | 7866/22,811 (34, 34-35)) |

8548/38,542 (22, 22-23) |

1562/8625 (18, 17-19)) |

| 3 Predictors | 8079/16,122 (50, 49-51)) |

9099/23,409 (39, 38-39)) |

1162/3360 (35, 33-36)) |

| 4 Predictors | 3528/5164 (68, 67-70)) |

4975/8693 (57, 56-58)) |

456/769 (59, 56-63)) |

| Overall | 23,959/64,789 (37, 37-37) |

27,585/114,803 (24, 24-24) |

4469/27,278 (16, 16-17) |

The overall performance of the model as applied to the retail health data was evaluated by comparing the areas under the receiver-operator characteristic curves. For patients aged 15 years and older, applying the Centor score to the retail health data yielded an AUC of 0.72. For patients aged 3 years and older, applying the McIsaac score to the retail health data achieved an AUC of 0.71.

Discussion

We evaluated two commonly used prediction models to classify risk of GAS among patients presenting with a painful throat. The purpose of a clinical prediction model is to provide clinicians with a practical and applicable tool to improve medical decision-making, the health of individual patients and the public health. The Centor score is one model that is particularly robust; it has withstood 30 years of changes in diagnostic testing, information technology, and population dynamics.19 Our study validated the Centor score in a clinical setting (retail health chain) with a less acutely ill population than the emergency department setting in which it was derived. While the Centor score was derived from a relatively small number of patients (n=286) seen in one setting during a single two month period, we analyzed data from multiple locations spanning more than one calendar year, mitigating the potential impact of seasonality as the data are collected throughout the normal peaks and ebbs of GAS incidence. Logistic regression selected, from among the candidate predictors shown in Table 3, the same four predictors that were chosen in Centor’s landmark paper.

With data from over 140,000 patients, our analyses provide precise interpretations of risk for each Centor score category, that still lie within the 95% confidence interval of Centor’s original study based on fewer than 300 patients. As we have shown previously, the recent, local incidence of GAS pharyngitis further improves the accuracy of estimating an individual patient’s risk of GAS.20 Ebbs and peaks of GAS occur naturally throughout the year, so the retail health data in our analyses collected over more than one year average over those variations and should provide more reliable characterization of the score than the original study by Centor conducted over two months.

Area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AUC) is one metric widely used to reflect the overall accuracy of a diagnostic test or overall performance of a clinical prediction model. The AUC of the Centor score in the retail health population (0.72) was lower than in Centor’s 1981 study (AUC=0.78) but the same as in Wigton’s validation study (AUC=0.72), arguing for the discriminating validity of this score. Clinical prediction models tend to perform less well in validation studies, but our data are consistent with the model’s performance in other validation studies.21 While McIsaac did not report an AUC on his original data, his score performed similarly to the others on this large data set.

The observed proportion of Minute Clinic patients testing positive according to clinical scores fell within the 95% confidence intervals of the Wigton and McIsaac validation studies (except for McIsaac score 0), supporting the calibration validity of the Centor and McIsaac scores.

Leveraging codified data from retail health clinics where uniform, algorithm-driven care is provided and data captured in a single electronic medical record, our study demonstrates the strengths of the Centor and McIsaac scores as useful tools in clinical decision-making. Though many clinicians in the primary care or emergency medicine setting do not routinely test adult patients who are either very likely or very unlikely to have GAS pharyngitis (i.e. those with Centor scores 0, 1 and 4), because MinuteClinic protocol mandates testing for all patients presenting with a painful throat, a further unique strength of our large validation study is ascertainment of GAS status on all subjects.

Limitations

Though all clinical and laboratory data were collected prospectively, the analyses were conducted retrospectively. There may be some variability in clinical interpretation of the Centor criteria by the nurse practitioners in the MinuteClinic setting; whether anterior cervical nodes are enlarged, for example, might be more subjective than other criteria such as temperature above 101.22 Further, data are not available for calculating inter- or intra-observer reliability.

Though very useful for diagnosing GAS, retail health data would be unlikely to detect most other bacterial causes of pharyngitis, including group C streptococcus or Fusobacterium necrophorum, the latter of which may cause severe disease especially in adolescents and young adults.23

All patients in the data set were symptomatic with sore throat, so our analyses do not address the important issue of the asymptomatic streptococcal carrier state. Serologic testing was not performed, so symptomatic patients with a positive test, were assumed to be true positives, not carriers.

Because these data were collected recently, we could not quantify potential changes in antibiotics attributable to the 2002 Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline24 and by the 2001 American College of Physicians guideline.25

Conclusions

Using a new, national-scale and uniform data source, electronically captured information from a retail clinic chain, we have validated the Centor and McIsaac scores as useful and valid tools for diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute pharyngitis.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Mentored Public Health Research Scientist Development Award K01HK000055 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), by R01 LM007677 and G08LM009778 from the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health and by Public Health Informatics Center of Excellence Award P01HK000088 from CDC. The authors thank CVS/Caremark and MinuteClinic for use of the data. Only the authors had a role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision, and the decision to submit for publication. Ethical approval: The Children’s Hospital Boston Committee on Clinical Investigation approved this database analysis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: AMF, VN, and KDM declare no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Financial disclosures: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005 Nov;5(11):685–694. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70267-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jan 18;344(3):205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snow V, Mottur-Pilson C, Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Mar 20;134(6):506–508. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, Brody CE, Link K. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1(3):239–246. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8100100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, Ives K, Carey M. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have strep throat? Jama. 2000 Dec 13;284(22):2912–2918. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIsaac WJ, Goel V, To T, Low DE. The validity of a sore throat score in family practice. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 2000 Oct 3;163(7):811–815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, Low DE. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with sore throat. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 1998 Jan 13;158(1):75–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laupacis A, Sekar N, Stiell IG. Clinical prediction rules. A review and suggested modifications of methodological standards. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1997 Feb 12;277(6):488–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasson JH, Sox HC, Neff RK, Goldman L. Clinical prediction rules. Applications and methodological standards. The New England journal of medicine. 1985 Sep 26;313(13):793–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509263131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linder JA, Chan JC, Bates DW. Evaluation and treatment of pharyngitis in primary care practice: the difference between guidelines is largely academic. Archives of internal medicine. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1374–1379. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.13.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costello D. A checkup for retail medicine. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008 Sep-Oct;27(5):1299–1303. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehrotra A, Liu H, Adams JL, et al. Comparing costs and quality of care at retail clinics with that of other medical settings for 3 common illnesses. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Sep 1;151(5):321–328. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-5-200909010-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollack CE, Armstrong K. The geographic accessibility of retail clinics for underserved populations. Arch Intern Med. 2009 May 25;169(10):945–949. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.69. discussion 950-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudavsky R, Pollack CE, Mehrotra A. The geographic distribution, ownership, prices, and scope of practice at retail clinics. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Sep 1;151(5):315–320. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-5-200909010-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodburn JD, Smith KL, Nelson GD. Quality of care in the retail health care setting using national clinical guidelines for acute pharyngitis. Am J Med Qual. 2007 Nov-Dec;22(6):457–462. doi: 10.1177/1062860607309626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. [Accessed October 5, 2011];Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement: Strep Pharyngitis Algorithm. http://www.icsi.org/respiratory_illness_in_children_and_adults__guideline_/respiratory_illness_in_children_and_adults__guideline__13116.html.

- 17.McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, Vanjaka A, Low DE. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. Jama. 2004 Apr 7;291(13):1587–1595. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wigton RS, Connor JL, Centor RM. Transportability of a decision rule for the diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis. Arch Intern Med. 1986 Jan;146(1):81–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aalbers J, O’Brien KK, Chan WS, et al. Predicting streptococcal pharyngitis in adults in primary care: a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signs and validation of the Centor score. BMC medicine. 2011;9:67. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fine AM, Nizet V, Mandl KD. Improved diagnostic accuracy of group a streptococcal pharyngitis with use of real-time biosurveillance. Annals of internal medicine. 2011 Sep 20;155(6):345–352. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-6-201109200-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Ales KL, Simon R, MacKenzie CR. Why predictive indexes perform less well in validation studies. Is it magic or methods? Arch Intern Med. 1987 Dec;147(12):2155–2161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiderman A, Marciano G, Bdolah-Abram T, Brezis M. Bias in the evaluation of pharyngitis and antibiotic overuse. Archives of internal medicine. 2009 Mar 9;169(5):524–525. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centor RM. Expand the pharyngitis paradigm for adolescents and young adults. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Dec 1;151(11):812–815. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Jr., Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 Jul 15;35(2):113–125. doi: 10.1086/340949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: background. Annals of internal medicine. 2001 Mar 20;134(6):509–517. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]