Introduction

These are interesting times for schizophrenia genetics. The last 5 years has seen unprecedented progress, moving us from debate about putative genetic models to an understanding that susceptibility involves a complex interplay of both common and rare genetic risk variants. Critical advances, achieved through the confluence of high-throughput genomics platforms and unparalleled collaboration (eg, the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium),1 have been the subject of excellent reviews elsewhere.2–4 The focus of this article is on a fresh challenge. How to move past gene discovery to understand pathophysiology and disease etiology?

So what do we know? In brief, this year is likely to see the confirmation by the PGC, at stringent levels of statistical significance, of more than 70 independent common risk alleles for schizophrenia from genome-wide association study (GWAS) analysis.5 To this we can add at least a dozen rare, structural genomic risk variants (chromosomal microduplications or deletions).4,6 Much still needs to be done. Because the common risk alleles individually have small effects on risk, collectively the more than 70 identified common risk loci may explain <5% of the total genetic variance in schizophrenia susceptibility (Ripke, personal communication). The structural variants have much larger effects (Odds Ratio [OR]=2–30) but are individually rare (present in <0.1% of controls) and are likely to make an even smaller contribution to the total risk. Present findings represent the first tangible pieces of a much larger genetic puzzle. That the genetic etiology is complex and only partially resolved has provoked criticism of the value of genomics research in schizophrenia, and medicine in general. This is to miss the point. The purpose of these studies is to understand biology, and this list of identified risk genes offers many new avenues for hypothesis-based research. In attempting to add more pieces to the puzzle, we know where to look, but until relatively recently have lacked the means to do so.7

A Roadmap to Future Gene Discovery?

Large numbers of small genetic effects, explaining at least 25% of the genetic variance in schizophrenia risk, remain to be identified.8 Some effects will be so small as to allude detection. However, the recent PGC findings represent a more than 5-fold increase in confirmed risk loci, achieved by doubling the sample size studied.5 This confirms a trajectory of discovery similar to that of other common disorders including Type 2 Diabetes (T2D), Ulcerative Colitis (UC), Crohn’s Disease (CD) and Psoriasis.9 So gene discovery through GWAS analysis will continue to be a powerful tool.

Rare sequence mutations represent the vast bulk of genomic variation. The rapid evolution of genomic sequencing opens up this unexplored genomic terrain and represents a philosophical transition from investigating what we hold in common as populations to what makes us individually unique. Shifting along this continuum, from relatively common variants investigated through GWAS analysis, the next step will be low-cost, high-throughput array-based assays of lower frequency variants, an approach that has been successful for other common disorders.10 Based on sequencing technology, there are likely to be improved calling methods to tackle the hitherto unexplored influence of smaller structural variants (<50kb).11 Most obviously, this technology allows us to access the huge reservoir of rare, or private sequence mutations in the human genome.12

The challenges for rare variant discovery are beyond the scope of this article (for review, see Sullivan et al.3). In short these include genetic (the “noise” generated by the background mutation rate, genetic heterogeneity, reduced penetrance); phenotypic (variable phenotype expression); and logistical (a coherent management strategy for the vast amount of data generated) factors. At this point too few schizophrenia exome studies have been published to allow meaningful comparison of results.13–15 However, from early reports, there appears to be an increased rate of de novo sequence mutations in schizophrenia cases compared with controls, and this may reflect, in part, the impact of greater paternal age.13–16 The transition to rare variant discovery is likely to be important, because low-frequency or rare variants are enriched for functional mutations compared with common risk variants.12 In practice, this means that rare mutations may have greater phenotypic effects, and the largest of these, such as some of the known structural risk variants, may have diagnostic or prognostic implications for carriers and their families.

It is likely that many more genetic pieces of the schizophrenia puzzle will emerge in the next 2–5 years. This will see a reorientation of the field. The focus will move beyond gene discovery to fitting the genetic pieces together to achieve meaningful insight into disease biology. Based on what we know, schizophrenia is a highly polygenic disorder, and for most cases genetic susceptibility is likely to represent disruption across a complex genetic network rather than individual gene effects. This will be true for most but not all cases. There are already identified subsets of individuals, with distinct genomic disorders (eg, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, 1q21.1 microdeletion syndrome), presenting as the schizophrenia syndrome.17–19 To what extent these, essentially rare diseases, contribute to the total syndrome is still uncertain. Functional studies of these rare high penetrance risk loci or specific risk genes (eg, Neurexin-1, VIPR2, ZNF804A)20–23 will be important. But deeper biological insight will require understanding of how a list of genes orchestrates the dynamic set of cellular processes that underpin schizophrenia.

Approaching Schizophrenia as a Network Disorder

Translating genetic variation into disease mechanisms requires the coordination of a complex network of cellular and intercellular functions. This network, termed the human interactome, incorporates interactions at the level of gene families, wider protein-protein interaction (PPI), metabolic pathways, regulatory networks, microRNA-gene networks, and interaction between genes and environmental factors, which will vary over time throughout the human lifespan. Despite this complexity, network-based approaches to human disease are increasingly feasible. Resources for investigating the interactome are expanding rapidly (reviewed by Vidal and colleagues).24 Intuitively, progress is dependent on the quality of information available for network analysis. At the present time the disease literature reflects the fact that some aspects of the network (eg, PPI) are better annotated than others (eg, regulatory networks). From a genetics perspective, notable successes have been achieved for other common traits and disorders where larger samples have been put together, quicker, than for psychiatric disorders.25–27

Until this year, the number of common risk loci available for schizophrenia analysis has been small (<15),28 so by necessity, analyses have included variants with much weaker association signals introducing more “noise” to the analysis. This has involved two types of approach. The first is based on risk profile scores accrued across large numbers of genetic markers as part of the “polygene score method” described by the International Schizophrenia Consortium.29 Hidden within these “noisy” schizophrenia risk profile scores are hundreds of small, unconfirmed genetic risk effects contributing to schizophrenia genetic variance. In support of the network concept, these effects are not random but are more likely to affect gene expression in adult brain than would be expected by chance and are disproportionately attributable to 2725 genes expressed in the central nervous system.8,30 The second, more traditional, approach has involved investigation of specific pathways with interesting provisional findings for PPI analysis of the DISC1 interactome31; for association with Cell Adhesion Molecule pathways32–34; and for a gene network potentially regulated by the microRNA mir-137.28

Harnessing information on a larger set of genetic risk variants will allow for more powerful analysis of genetic networks in schizophrenia. Maximizing the information available will ideally require methods of incorporating common and rare genetic risk variants into pathway or network analysis. But stepping beyond genetics discovery, this will also require integration across different levels of the network. To understand gene function we need to incorporate information about gene expression across human brain development.35 But networks are dynamic, and it will also be important to consider how transcriptional mechanisms respond to discrete environmental risk factors and also to the impact of social networks.36

What Can We Learn From Biological Networks?

Biological networks are not random but evolve and are structured based on a set of underlying organizing principles. By understanding these principles we can apply them to undertake a structured approach to investigating schizophrenia as a network disorder.37

First, if a network is random, most nodes in the network will have approximately the same number of links, and highly connected nodes (also termed hubs) will be uncommon. In contrast, biological networks tend to have a small number of highly connected hubs that hold the network together. Identifying hubs within the network may be an important step in understanding biological processes as they may represent targets for therapeutic intervention.

Second, in any network the paths between nodes are usually short. This means that most nodes in a biological network are separated by only a few interactions as has been demonstrated for both protein interaction and metabolic networks.38,39 Extending this principle, proteins that are involved in the same disease show a greater propensity to interact with each other.40 So if we identify disease genes, other risk genes are likely to be found in the same local vicinity, or module, of the network. The problem becomes one of trying to identify the topographical modular structure of the network. This can be achieved through a growing number of network clustering algorithms.41–43 That more approaches are being developed is indicative that none are ideal, and where modules are identified it may be important to validate through functional annotation experimentally (eg, in PPI networks) or across different levels of network function.

The attraction of this approach is that it can substantially reduce the search space for genomic studies. Identified modules or local subnetworks can by directly tested to identify enrichment of common risk variation and rare functional mutations. The classic example, from the rare variant literature, is the 23 genes implicated in inherited forms of ataxia identified through a subnetwork of 54 proteins.44 A very different approach, described by Rossin et al. (2011),45 evaluates the quality of evidence for PPI between identified risk genes and uses this information in building a network. With this method the authors demonstrated that proteins encoded by genetic loci associated with a number of disorders or traits (RA, CD, height and lipid levels) are significantly connected compared with random networks. Two different applications of the classical approach have been reported in schizophrenia.46,47 One of these methods, described by Gilman and colleagues,46 integrated both common and rare risk variation in their analysis. Both this, and the GWAS-based analysis described by Jia and colleagues,47 reported association with numerous different aspects of neuronal function. With more risk loci being identified for schizophrenia, these types of analytical approaches are likely to become more common with an increasing focus on identifying evidence for convergence across methods and data sets.

Third, interactions may be at the level of coexpression or shared function, rather than physical protein interaction. Applying a gene coexpression analysis method, Voineagu et al. (2011)48 recently reported discrete modules of coexpressed genes associated with autism and wider differences in transcriptome organization between autistic and normal brain. Interestingly, the transcriptome level changes showed convergence with known autism risk genes and genetic association signals, suggesting a plausible mechanism whereby a network of genes alters regulation of a transcriptional network mediating autism risk. Similar efforts to link genetic risk variants to gene expression networks are beginning to emerge in schizophrenia.49,50

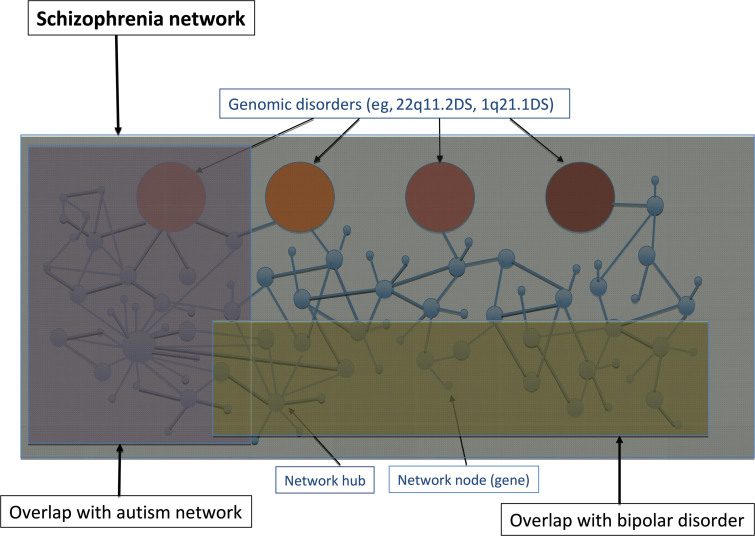

Fourth, highly connected nodes (hubs) that represent essential components in the network have particular properties. By virtue of having more interactions, hub proteins are likely to be involved in more biological processes and more diseases. One interpretation of the diverse developmental outcomes associated with structural risk variants (an illustrative example is 1q21.1 deletions)51 is that these loci represent examples of such “disease” hubs (see figure 1). So, careful characterization of the range of phenotypes associated with such loci will be important, and they are likely to represent key network components for targeted functional interrogation.

Fig. 1.

A model of the schizophrenia network demonstrating subnetworks, network hubs and nodes, and potential for overlaps with other disorders.

Fifth, common and rare risk variants may impact differently on the network. Much of our understanding of biological systems comes from simple model systems and is based on analysis of loss-of-function mutations. Most common risk variants are likely to have much more subtle effects on gene function. By way of illustration, the list of risk genes implicated in schizophrenia by common risk variants includes CACNA1C and TCF4, genes where functional mutations cause severe developmental syndromes (Timothy syndrome and Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, respectively).52,53 As such these might be seen as disease hubs. However, there are also likely to be points of divergence for common and rare risk variants in gene networks, where loss-of-function mutations of essential proteins are not compatible with life.

Finally, diseases may share hubs, but disease networks are also likely to overlap (see figure 1). This is a key emerging theme from investigation of other common disorders. For example, there are many shared loci involving autoimmune and inflammatory processes being identified across a range of common disorders (eg, CD, UC, T1D, Graves Disease, Coeliac Disease, and Psoriasis).54,55 There is significant evidence already for network overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and, to a lesser extent, autism.29,56,57 Cross disorder analysis is underway comparing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism. The findings from structural variants and for metabolic dysfunction in schizophrenia, arguer for a wider analysis including other developmental (intellectual disability, seizure disorder) and metabolic disorders (obesity, lipid metabolism, T2D).

Conclusion

Beginning to put together the relationships between genes strikes to the heart of a fundamental challenge in schizophrenia research. Because we are learning from cancer research and other fields in medicine, clinical or even pathological diagnostics may bear little relation to the underlying molecular mechanisms of disease. Progress in these fields has required a transition from conceptual models of disease (or disorder) to mechanistic models of disease processes. The schizophrenia syndrome is likely to capture different molecular mechanisms, which represent discrete subtypes or even different diseases with the same common endpoints.58 By understanding the relationship between genes and identifying network subcomponents, these will become the models or building blocks for schizophrenia research. Such building blocks can be validated and functionally interrogated by model systems. This is likely to involve high-throughput screening in simple systems to identify common functions (eg, of mechanisms involving ion-channel function or cytoskeleton dynamics).59 Such mechanisms will, in turn, require more complex dissection, eg in mouse or human iPS models,60 with comparison across systems (for an elegant example, see Nithianantharajah61). From such foundations we can advance new, focused hypotheses. Do subnetworks or molecular mechanisms map to neural circuits, perhaps identifiable by diffusion tensor imaging? How do network modules relate to clinical symptoms, outcome or treatment response? Or address wider questions. Is the burden of risk variants important to illness progression in high-risk populations? Does total genetic burden relate to outcome? How does genetic burden interact with environmental risk? None of these are abstract questions. We urgently need new strategies for prevention, early intervention, and treatment to tackle this most challenging of disorders.

Funding

Science Foundation Ireland (08/IN.1/B1916 to A.C.).

Acknowledgments

The author has declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Sullivan PF. The psychiatric GWAS consortium: big science comes to psychiatry. Neuron. 2010; 68: 182–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Owen MJ. Implications of genetic findings for understanding schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012; 38: 904–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O’Donovan M. Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2012; 13: 537–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Malhotra D, Sebat J. CNVs: harbingers of a rare variant revolution in psychiatric genetics. Cell. 2012; 148: 1223–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ripke S. XXth World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics; 14-18 October 2012; Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guha S, Rees E, Darvasi A,, et al. for the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia Consortium and the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 Implication of a Rare Deletion at Distal 16p11.2 in Schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013. 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ,, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009; 461: 747–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee SH, DeCandia TR, Ripke S. ; Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study Consortium (PGC-SCZ); International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC); Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia Collaboration (MGS) Estimating the proportion of variation in susceptibility to schizophrenia captured by common SNPs. Nat Genet. 2012; 44: 247–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim Y, Zerwas S, Trace SE, Sullivan PF. Schizophrenia genetics: where next?. Schizophr Bull. 2011; 37: 456–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM,, et al. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium; Meta-Analyses of Glucose and Insulin-related traits Consortium (MAGIC) Investigators; Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium; Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network–Type 2 Diabetes (AGEN-T2D) Consortium; South Asian Type 2 Diabetes (SAT2D) Consortium; DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012; 44: 981–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fromer M, Moran JL, Chambert K,, et al. Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am J Hum Genet. 2012; 91: 597–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacArthur DG, Balasubramanian S, Frankish A,, et al. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A systematic survey of loss-of-function variants in human protein-coding genes. Science. 2012; 335: 823–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu B, Roos JL, Dexheimer P,, et al. Exome sequencing supports a de novo mutational paradigm for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2011; 43: 864–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Need AC, McEvoy JP, Gennarelli M,, et al. Exome sequencing followed by large-scale genotyping suggests a limited role for moderately rare risk factors of strong effect in schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2012; 91: 303–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu B, Ionita-Laza I, Roos JL,, et al. De novo gene mutations highlight patterns of genetic and neural complexity in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2012; 44: 1365–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kong A, Frigge ML, Masson G,, et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature. 2012; 488: 471–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murphy KC. Schizophrenia and velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Lancet. 2002; 359: 426–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stefansson H, Rujescu D, Cichon S,, et al. GROUP Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008; 455: 232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. International Schizophrenia Consortium Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008; 455: 237–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kirov G, Rujescu D, Ingason A, Collier DA, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ. Neurexin 1 (NRXN1) deletions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009; 35: 851–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vacic V, McCarthy S, Malhotra D,, et al. Duplications of the neuropeptide receptor gene VIPR2 confer significant risk for schizophrenia. Nature. 2011; 471: 499–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levinson DF, Duan J, Oh S,, et al. Copy number variants in schizophrenia: confirmation of five previous findings and new evidence for 3q29 microdeletions and VIPR2 duplications. Am J Psychiatry. 2011; 168: 302–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O’Donovan MC, Craddock N, Norton N,, et al. Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia Collaboration Identification of loci associated with schizophrenia by genome-wide association and follow-up. Nat Genet. 2008; 40: 1053–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vidal M, Cusick ME, Barabási AL. Interactome networks and human disease. Cell. 2011; 144: 986–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lango AH, Estrara K, Lettre G,, et al. Hundreds of variants clustering in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010; 467: 832–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP,, et al. DIAbetes Genetics Replication and Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat Genet. 2012; 44: 991–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Virgin HW, Todd JA. Metagenomics and personalized medicine. Cell. 2011; 147: 44–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ripke S, Sanders AR, Kendler KS,, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat Genet. 2011; 43: 969–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Purcell SM, Wray NR,, et al. International Schizophrenia Consortium Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009; 460: 748–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Richards AL, Jones L, Moskvina V,, et al. Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia Collaboration (MGS); International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC) Schizophrenia susceptibility alleles are enriched for alleles that affect gene expression in adult human brain. Mol Psychiatry. 2012; 17: 193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Camargo LM, Collura V, Rain JC,, et al. Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 Interactome: evidence for the close connectivity of risk genes and a potential synaptic basis for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007; 12: 74–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jia P, Wang L, Fanous AH, Chen X, Kendler KS, Zhao Z. International Schizophrenia Consortium A bias-reducing pathway enrichment analysis of genome-wide association data confirmed association of the MHC region with schizophrenia. J Med Genet. 2012; 49: 96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lips ES, Cornelisse LN, Toonen RF,, et al. International Schizophrenia Consortium Functional gene group analysis identifies synaptic gene groups as risk factor for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2012; 17: 996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O’Dushlaine C, Kenny E, Heron E, et al. International Schizophrenia Consortium Molecular pathways involved in neuronal cell adhesion and membrane scaffolding contribute to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder susceptibility. Mol Psychiatry. 2011; 16: 286–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen Institute for Brain Science. http://www.brain-map.org http://www.brain-map.org Allen brain atlas.

- 36. Meyer-Lindenberg A, Tost H. Neural mechanisms of social risk for psychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2012; 15: 663–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barabási AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011; 12: 56–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barabasi AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999; 286: 509–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jeong H, Tombor B, Albert R, Oltvai ZN, Barabási AL. The large-scale organization of metabolic networks. Nature. 2000; 407: 651–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goh KI, Cusick ME, Valle D, Childs B, Vidal M, Barabási AL. The human disease network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007; 104: 8685–8690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ravasz E, Somera AL, Mongru DA, Oltvai ZN, Barabási AL. Hierarchical organization of modularity in metabolic networks. Science. 2002; 297: 1551–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Enright AJ, Van Dongen S, Ouzounis CA. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30: 1575–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rhissorakrai K, Gunsalus KC. MINE: Module Identification in Networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011; 12: 192 doi:10.1186/ 1471-2105-12-192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lim J, Hao T, Shaw C,, et al. A protein-protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration. Cell. 2006; 125: 801–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rossin EJ, Lage K, Raychaudhuri S,, et al. International Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Constortium Proteins encoded in genomic regions associated with immune-mediated disease physically interact and suggest underlying biology. PLoS Genet. 2011; 7: e1001273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gilman SR, Chang J, Xu B,, et al. Diverse types of genetic variation converge on functional gene networks involved in schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci. 2012; 15: 1723–1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jia P, Wang L, Fanous AH, Pato CN, Edwards TL, Zhao Z. International Schizophrenia Consortium Network-assisted investigation of combined causal signals from genome-wide association studies in schizophrenia. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012; 8: e1002587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Voineagu I, Wang X, Johnston P,, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature. 2011; 474: 380–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roussos P, Katsel P, Davis KL, Siever LJ, Haroutunian V. A system-level transcriptomic analysis of schizophrenia using postmortem brain tissue samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012; 69: 1205–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lee SA, Tsao TT, Yang KC,, et al. Construction and analysis of the protein-protein interaction networks for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011; 12 Suppl 13 S20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Haldeman-Englert C, Jewett T. 1q21.1 Microdeletion. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Splawski I, Timothy KW, Priori SG,, et al. Timothy Syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993–2006. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Blake DJ, Forrest M, Chapman RM, Tinsley CL, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ. TCF4, schizophrenia, and Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 2010; 36: 443–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Das J, Mohammed J, Yu H. Genome-scale analysis of interaction dynamics reveals organization of biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2012; 28: 1873–1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cotsapas C, Voight BF, Rossin E,, et al. FOCiS Network of Consortia Pervasive sharing of genetic effects in autoimmune disease. PLoS Genet. 2011; 7: e1002254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Björk C,, et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009; 373: 234–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sullivan PF, Magnusson C, Reichenberg A,, et al. Family history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as risk factors for autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012; 69: 1099–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Corvin AP. Two patients walk into a clinic...a genomics perspective on the future of schizophrenia. BMC Biol. 2011; 9: 77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Burne T, Scott E, van Swinderen B,, et al. Big ideas for small brains: what can psychiatry learn from worms, flies, bees and fish?. Mol Psychiatry. 2011; 16: 7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brennand KJ, Simone A, Jou J,, et al. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011; 473: 221–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nithianantharajah J, Komiyama NH, McKechanie A, et al. Synaptic scaffold evolution generated components of vertebrate cognitive complexity. Nat Neurosci. 2013; 16: 16–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]