Abstract

Banner Health in the Phoenix, AZ, metropolitan area provides individuals in a behavioral health crisis with an alternative to presenting to an Emergency Department (ED). By implementing a process to quickly move patients out of our ED, our health care system has been able to greatly reduce the hold time for behavioral health patients. Through access to psychiatric clinicians around the clock at the Banner Psychiatric Center, patients now receive the appropriate treatment and needed care in a timely manner. Finally, disposition of patients into appropriate levels of care has freed up acute care Level 1 beds to be available to patients who meet those criteria.

Introduction

Banner Health is one of the largest health care systems in the western US with 23 hospitals and health care facilities in 7 states—Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Nebraska, Nevada, and Wyoming—and more than 30,000 employees.

In Arizona, Banner Health has 12 hospitals and 9 Emergency Departments (EDs) in the metropolitan Phoenix area with a combined total of close to 1500 adult patient visits per day. Banner Health is the largest private provider of inpatient mental health services in Arizona. A high percentage of behavioral health patients use the ED to access services in the Phoenix metropolitan area. Even though these patients represent a relatively small percentage of total ED visits, they tend to have a disproportionate impact on ED throughput because they often require additional resources (often 1:1 observation) and have a very long length of stay in the ED.

EDs are one of the cornerstones of America’s health care delivery system. The emergency room model allows the general public to have 24-hour access to trained medical personnel, including physicians and nurses who have the ability not only to assess the patient’s crisis but also to intervene and to stabilize the crisis in most instances.

ED overcrowding has been a national problem for many years. Although the contributory factors are complex, nearly all parties agree that behavioral health patients in the ED contribute to this problem.

Problem Statement

A 2004 survey by the American College of Emergency Physicians, in partnership with mental health organizations including the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, the National Mental Health Association, and The American Psychiatric Association found that psychiatric patients wait in EDs more than twice as long as other patients while arrangements are made for psychiatric services elsewhere. According to 81% of the 340 survey respondents, the increase in those patients holding for an inpatient psychiatric bed negatively affects the care of other patients, reduces availability of ED staff for other patients, and contributes to longer waits for patients in the waiting room and to patient frustration.1

Patients with psychiatric and drug- or alcohol-related complaints may represent a disproportionate number of longer wait times in the ED.2 Furthermore, a British study found that suicidal and self-harming patients presenting to an ED who did not receive a psychiatric assessment were twice as likely to commit further self-harm in the next year as those who were evaluated.3 Almost half of the patients who did not receive a timely evaluation left without treatment.4

A May 2011 article in Health Leaders Media noted that health care reform would require new ways to think about the delivery of care.5 The ED can become a U-turn lane that channels patients out of a hospital to a less expensive setting.5 The same article points out that those patients entering the ED for physical complaints do not mingle well with patients who may have behavioral presentations that are aggressive or bizarre.

In 2009, the average hold time for a behavioral health patient in Banner Health’s EDs was 14 hours to 16 hours per patient vs 3 hours to 5 hours for nonbehavioral health patients. That year, Banner Health experienced 150,000 hold hours for behavioral health patients in its EDs. Each individual ED had to arrange for the disposition of these patients, who ended up being admitted as inpatients approximately 75% of the time.

Some of the contributory factors to this long hold time included an imbalance of inpatient and outpatient services, and insufficient capacity because of an outdated and ineffective patient care model. These factors manifested themselves in several ways inside the hospital, including the following:

Demands for inpatient behavioral health beds exceeded the supply of those beds.

Appropriate treatment for the patient with behavioral health issues was delayed while that person awaited placement in an inpatient bed, and often the patient’s condition deteriorated. Delays in receiving crisis stabilization services significantly increased the risk of physical injury to the patient and to others around him or her.

Patients were being admitted to the highest levels of care because on-site assessment by a psychiatric provider was unavailable and there was a lack of community resources. Many of these patients could have been stabilized and treated in an outpatient setting.

In the ED setting, nonbehavioral health patients and families were often exposed to unsettling verbal and physical outbursts from these patients and witnessed the patients being physically restrained.

The increased hold hours decreased the ED’s capability and capacity at times to treat and to accept patients in need of acute medical care.

The reduced bed and staffing capacity in the EDs caused delays in treatment, reduced patient satisfaction, and increased the risk of patients leaving without treatment.

Of all the medical specialties, psychiatry is the only one not to use the ED model of health care delivery. Most EDs have no psychiatric services available. Some EDs have set aside space specifically for patients in psychiatric crisis and, depending on the facility, have some level of provider, usually a therapist or social worker, available to complete an assessment. Many EDs do not have a psychiatric provider available 24 hours per day, 7 days a week (“24/7”) who can intervene and stabilize the crisis. Because of the lack of psychiatric providers available at the time of presentation, these patients invariably are transferred to the first available psychiatric inpatient facility.

Previous Options

Before the development of the Banner Psychiatric Center and the centralization of Banner Health’s Regional Patient Placement Office, there were few options for individuals presenting to busy EDs with a psychiatric illness.

In most EDs the protocol was to have the patient assessed by a midlevel behavioral health provider, and if that provider thought the patient met inpatient criteria, the wait for a bed would begin.

Unfortunately, without a psychiatrist or psychiatric nurse practitioner available, crisis intervention with appropriate medication and treatment planning was often lacking. Without a coordinated central placement system, each ED would be trying to find any available bed either inside or outside the hospital system. Because of the lack of coordination, information being sent to the receiving facility was often missing and extensive time was spent in reevaluating the patient for the next level of care. Once again, the receiving facilities—depending on the time of day—might or might not have a psychiatrist present at the facility.

Although many EDs have a psychiatrist on-call, patients requiring behavioral help could languish in an ED for hours or days before transferring to a behavioral health hospital, then wait another 12 to 24 hours to see a psychiatrist face-to-face.

The outcome for EDs was that increased use of valuable resources over an extended period was needed to manage these patients. Beds that could have been used to treat patients with medical issues were unavailable. Behavioral health patients, in other words, were not receiving the optimum level of care to address their illness.

Methods

Resources and Partnerships

To explore solutions, in 2009 Banner Health partnered with the physician group Connections Arizona to explore the possibility of creating a new model of care that would address these issues. Together, a coordinated delivery of care system was developed. Before this time, it was widely accepted that there were not enough inpatient behavioral health beds in Maricopa County, AZ (which includes Phoenix and Scottsdale). This was inaccurate, as the problem was that most patients who presented to EDs or psychiatric hospitals were being admitted into the highest level of care because of the lack of other options. This resulted in an increasing percentage of patients who were admitted and discharged from an acute care inpatient setting within 24 to 48 hours. Involuntarily admitted (“involuntary”) patients were a major issue because the Urgent Psychiatric Center in downtown Phoenix was often on diversion because of capacity issues, as the center treated both the involuntary and voluntary population.

Connections Arizona had successfully developed a model of care that had greatly changed the way mental health was delivered in Dallas, TX. Connections Arizona owns and operates the Urgent Psychiatric Care Center in downtown Phoenix.

As the two organizations worked together, it became clear that the city of Phoenix required a second center similar to the Urgent Psychiatric Care Center, which could provide psychiatric crisis assessment and evaluation in a safe and therapeutic environment. In addition, a comprehensive plan to educate and to standardize behavioral health care in the EDs would need to be developed.

Solutions

A new care model was developed with the goal of getting behavioral health patients from the ED to a safe, secure, and appropriate care setting in as timely a manner as possible. An emergency psychiatric center, the Banner Psychiatric Center, was opened in September 2010 and is staffed 24/7 by a psychiatrist or behavioral health nurse practitioner along with other behavioral health support staff.

Additionally, a transfer process was developed using a regional transfer center at Banner Health known as the Regional Patient Placement Office, which helps in the placement of medical patients. This centralized service is essentially a call center that is staffed 24/7 by registered nurses who match requests for patient transfers to available resources. The office facilitates an average of more than 2000 transfers per month, including more than 400 behavioral health patients transferred from the ED. Behavioral health services were put under this centralized model, which enabled the Regional Patient Placement Office to facilitate the transfers from the EDs to the Banner Psychiatric Center in a timely manner and to know bed availability within Banner Health and the community.

Patients are assessed shortly after arrival at the Banner Psychiatric Center, are stabilized, and are either discharged to the community or admitted to the inpatient setting. The decision was made to accept only adult voluntary patients at the Banner Psychiatric Center, allowing the Urgent Psychiatric Care Center downtown to concentrate on involuntary patients.

Development of the new care model involved the following six-step process:

Create a long-range plan and integrate behavioral health services into the Regional Patient Placement Office.

Build the physical facility for the Banner Psychiatric Center and devise program goals and services.

Educate ED staff and develop a patient-flow process to the center.

Standardize ED processes related to behavioral health patients.

Implement and use telemedicine services.

Address the needs of behavioral health patients with comorbidity.

The steps are described in detail here.

Step 1 was to develop a short-term and long-term plan for the Banner Psychiatric Center. The first act was to integrate behavioral health into Banner Health’s existing Regional Patient Placement Office. This centralized placement system had proved effective in rapid placement of patients with medical issues throughout Banner Health’s network of acute care hospitals in Arizona. Additional staff was added and received training specific to placement of behavioral health patients. Since January 2010, when this system was put in place, the Regional Patient Placement Office has triaged more than 10,000 behavioral health patients.

Step 2 involved Banner Health building a state-of-the-art assessment and observation unit based on the medical model of a “psychiatric emergency room.” This unit was located on the grounds of the freestanding 96-bed Banner Behavioral Health Hospital in Scottsdale, AZ. The building was renovated and relicensed as the Banner Psychiatric Center. The center is approximately 7000 sq ft and includes a separate entrance; a lobby with a waiting room and interview rooms; a 23-hour observation area with 24 recliners, seclusion and restraint rooms; a medication room, and additional interview rooms. A separate police and ambulance entrance was created, and that area has a restroom, shower, seclusion and restraint room, and interview room.

The hub of the center is the staff observation and communication area, which has direct viewing of the 23-hour observation area and cameras for views of the entire facility. Every aspect of the facility was geared for maximum safety and security for the patients. The center is staffed 24/7 with psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, registered nurses, behavioral health technicians, and crisis interventionists. The Banner Psychiatric Center provides behavioral health services to behavioral health patients for a period less than 24 hours.

A model also was established for the EDs that allowed for clinician-to-clinician dialogue and review.

Program goals included the following:

Provide person-centered behavioral health services for adults (aged 18 and older) who are experiencing psychiatric symptoms and come to the center voluntarily.

Provide services in a safe, secure, recovery-focused setting using the least restrictive and intrusive levels of behavioral health services.

Reduce or eliminate psychiatric and behavioral health symptoms.

Reduce resource consumption and staffing in the acute care EDs, particularly those associated with sitters, who are assigned to holding behavioral health patients.

Defer 70% of behavioral health inpatient admissions to outpatient treatment settings.

Positively affect the care delivery model in Maricopa County.

Optimize patient throughput and financial performance in Banner Health’s acute care EDs by reducing the hold times and related expenses of behavioral health patients.

Services provided by the Banner Psychiatric Center include emergency intake and assessment, behavioral health crisis intervention, medication services and stabilization, counseling, referral to community resources, and coordination of care with service clinicians.

Step 3 was the development of a patient-flow process and education for ED staffs to facilitate timely transfer of patients from the ED to the Banner Psychiatric Center.

Step 4, which is a work in progress, involves standardization of processes related to behavioral health patients throughout the Banner Health EDs.

At Banner Health, multidisciplinary teams of physicians and other clinicians who examine emerging issues and opportunities for improvement in specific clinical areas help develop both expected and recommended clinical practices for systemwide implementation on the basis of evidence. The Behavioral Health Clinical Consensus Team developed a medical manageability criteria plan. Behavioral health units in medical centers have more resources available to them to address comorbid medical concerns than does a freestanding behavioral health facility. Behavioral health facilities often face additional challenges that the ED staff may not be aware of, such as the danger of taking patients in whom tubes have been inserted.

An additional component of this process is the use of a standardized electronic assessment platform. To add to the safety and efficacy of placing behavioral health patients, Banner Health has contracted with Pasadena, CA–based Hippocrates Gate LLC to use AccessHSI, the company’s Web-based behavioral health patient assessment and level of care tool. AccessHSI will be employed for the initial behavioral health patient assessment and become an integral part of the electronic medical record.

Alternatives are now available for patients experiencing a mental health crisis other than going to an ED.

Step 5 involves exploring how to provide more comprehensive behavioral services to the Banner Health EDs using an electronic intensive care unit, or “eICU,” model based at the Banner Psychiatric Center. Banner Health is the first health care provider in the Phoenix metropolitan area to use telecommunications technology to monitor patients from hundreds of miles away. When finalized, the vision is to provide 24/7 telemedicine services from the Banner Psychiatric Center to all Banner Health EDs in Arizona as well as Banner facilities in other western states.

Step 6 is addressing the needs of patients with a comorbid medical problem. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation report6 found that more that 68% of adults with a mental disorder had at least one medical condition, and 29% of those with a medical disorder had a comorbid mental health condition, on the basis of the 2003 National Comorbidity Survey Replication. This report indicates that individuals with mental illnesses are more likely than those without mental illness to have physical health ailments.6

Results

Since opening in September 2010, the Banner Psychiatric Center has treated more than 6000 patients. There was a daily average of 17 arrivals, 11 of which were transfers from the EDs and 6 of which were walk-ins. Hold times in the EDs decreased by more than 40% for this patient population, from a range of 14 to 16 hours to 8 to 10 hours. Additionally, less than 50% of the patients who presented to the Banner Psychiatric Center were admitted later to an inpatient unit. Before implementation of the center, that rate was 75%.

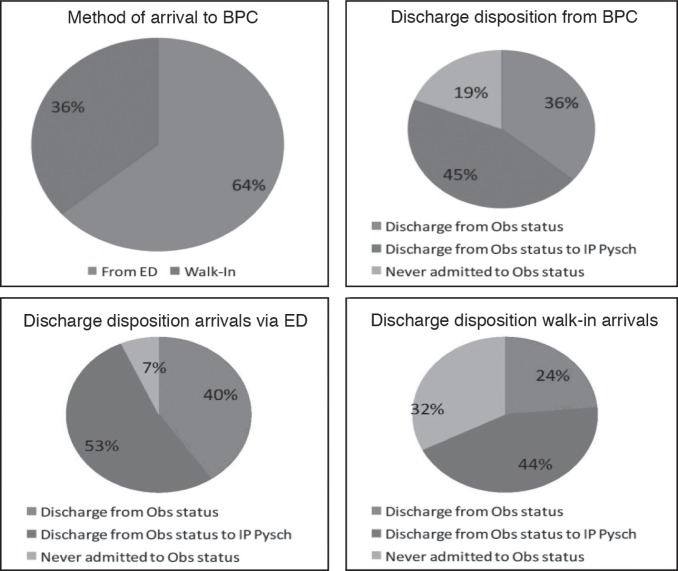

Alternatives are now available for patients experiencing a mental health crisis other than going to an ED. Of the more than 4000 patients who visited the Banner Psychiatric Center between September 2010 and April 2011, 36% were walk-in patients to the center (Figure 1, top left). The conclusion can be drawn that before this model and level of care became available, those individuals would have gone to a medical center ED to seek treatment. The other 64% of patients at the Banner Psychiatric Center were transferred from EDs (Figure 1, top left).

Figure 1.

Breakdown of patients at Banner Psychiatric Center, from September 2010 to March 2011, by method of arrival and discharge disposition.

BPC = Banner Psychiatric Center; ED = Emergency Department; IP Psych = inpatient psychiatric unit; Obs = observation.

Opening the Banner Psychiatric Center also resulted in more bed availability at the Urgent Psychiatric Care Center for involuntary patients, leading to more rapid placement from the Banner Health EDs for both involuntary and voluntary patients.

Before the opening of the Banner Psychiatric Center, the percentage of patients assessed, treated, and released from Banner Behavioral Health Hospital within 24 to 48 hours had steadily risen over the past 2 years. These patients generally have presented to the hospital or from an ED between 7 pm and 7 am. The prior unavailability of an onsite evaluation by a psychiatrist or psychiatric nurse practitioner at the ED led to admitting most of these patients to the highest level of care until they could be seen the next day. These patients are now being admitted and discharged from the Banner Psychiatric Center’s observation level of care beds. This has freed up acute inpatient beds in Banner Behavioral Health Hospital to be able to accept those patients who truly require that level of care.

Of the patients arriving at the Banner Psychiatric Center between September 2010 and April 2011, 19% were assessed and discharged without observation. Of the patients who were admitted into the center’s 23-hour observation area, 36% were discharged from that level of care. The remaining 45% of patients were admitted into an acute care inpatient bed at some time during that 23-hour period (Figure 1, top right). Patients who arrived from an ED were more likely to require observation than were walk-in arrivals, and they were more likely to need psychiatric hospitalization (Figure 1, bottom).

Conclusion

Banner Health has provided individuals in a behavioral health crisis with an alternative to presenting to an ED. Through implementation of a process to quickly move patients out of our EDs, we have greatly reduced the hold hours for behavioral health patients. Through access to psychiatric clinicians 24/7, patients are now receiving the appropriate treatment and needed care in a timely manner. Through disposition into appropriate levels of care, acute care Level 1 beds have been freed up to provide availability to patients who meet those criteria.

Acknowledgments

The Banner Psychiatric Center project was funded, with support of Banner Health senior leadership, through capital funding and charitable giving to Banner Health Foundation. Contractual agreements were made with payers to support patient admissions once operation of the Banner Psychiatric Center began.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Every Patient Has a Story

In psychiatry, the patient who comes to us has a story that is not told, and which as a rule no one knows of … . Therapy only really begins after the investigation of that wholly personal story. It is the patient’s secret, the rock against which he is shattered. If I know his secret story, I have a key to the treatment. The doctor’s task is to find out how to gain that knowledge … . The problem is always the whole person, never the symptom alone.

— Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Carl Gustav Jung, 1875–1961, Swiss psychotherapist and psychiatrist who founded analytical psychology

References

- 1.Mulligan K. ER docs report large increase in psychiatric patients. Psychiatr News [serial on the Internet] 2004. Jun 18, [cited 2012 Sep 24];39(12):10 [about 1 p]. Available from: http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/newsar-ticle.aspx?articleid=107619.

- 2.Wartman SA, Taggart MP, Palm E. Emergency room leavers: a demographic and interview profile. J Community Health. 1984 Summer;9(4):261–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01338726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickey L, Hawton K, Fagg J, Weitzel H. Deliberate self-harm patients who leave the accident and emergency department without a psychiatric assessment: a neglected population at risk of suicide. J Psychosom Res. 2001 Feb;50(2):87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00225-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weissberg MP, Heitner M, Lowenstein SR, Keefer G. Patients who leave without being seen. Ann Emerg Med. 1986 Jul;15(7):813–7. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80380-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(86)80380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark C. The new ED: keep patients out (but happy) Health Leaders Media [serial on the Internet] 2011. May 13, [cited 2012 Sep 24]: [about 4 p]. Available from www.healthleader-smedia.com/content/MAG-266111/The-NewED-Keep-Patients-Out-but-Happy.html.

- 6.Druss BG, Reisinger WE. The Synthesis Project. Research Synthesis Report no. 21. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2011. Feb, Mental disorders and medical comorbidity; pp. 1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]