Abstract

Objective:

This study identified and measured common patterns of patients’ positive care experiences during inpatient palliative consultation, and helped better understand how the journey of discovery experienced by both patients and life-care consult teams can be used to improve the quality of care.

Methods:

We administered questionnaires to a convenience sample of 25 patients who were referred to inpatient palliative care for a goals-of-treatment consult between April 2010 and May 2012.

Results:

The codified responses to questionnaires revealed the perspectives of our patients rather than predicting outcomes. Respondents identified six areas of satisfaction: treatment with dignity and respect by the hospital health care team; after life-care planning consultation, patients felt they were better informed of their illness and medical context; 95% of all patients who responded felt their overall experience was excellent; all respondents felt the life-care planning consultation helped them form a treatment plan; all patients who responded believed their cultural beliefs and values were respected; and all responding patients noted that the inpatient palliative care team adequately addressed pain and symptom control.

Conclusion:

We were encouraged by our findings: the feedback from patients and families showed us we were effective, from their perspective, in helping them shape their treatment journey. It also emphasized where we could have been even more effective in improving our communication.

Introduction

Inpatient palliative care is an essential component of Kaiser Permanente’s (KP’s) approach to improving the quality of continuing care service to our patients and their families. Consistently honoring patient-centered decision making is a salient aspect of this approach. Patients and their families are given opportunities to discuss treatment values and nonmedical concerns with an interdisciplinary team that helps them better understand their illness and prognosis.

We used a qualitative approach to the research question, Why do patients find inpatient palliative care consultation helpful? We emphasized a holistic perspective in attempting to understand the social context of our patient population at the KP South Bay Medical Center in Harbor City, CA. Qualitative methods allowed us to reach a new understanding when interpreting the data.

Our study process was based on the following concepts, which are important components of grounded theory: reality is socially constructed and context related; discovery of meaning is an important basis of knowledge; and discovery and analysis will proceed iteratively and not sequentially. Grounded theory emphasizes that reality is rooted in the existential and is always dynamic.1 This is why we discussed the patients’ living, ongoing personal narratives.2 We were interested in learning how to understand a clinical process or treatment situation from the patient’s perspective. We analyzed the categories and phases of their medical course. Detailed exploration and theoretic sensitivity with respect to inpatient palliative consultation shaped the social construction for each patient. We discovered answers to our research question by grounding our analysis in the data.

Honest communication about choices and outcomes was important when helping patients cope more effectively with their illness, and our guidance allowed patients to express their own wishes and priorities during treatment planning.3 Our questions focused on ascertaining each patient’s experience so as to tailor advance care planning and discussion of treatment to their specific situation.

Objective

The objective of this study was to identify and to measure, by qualitative analysis, common patterns in patients’ positive care experiences and to explain how the journeys of discovery experienced by both patients and inpatient palliative care consultation teams can be used to improve the quality of care. We were able to more thoroughly understand how the patient’s standpoint guided our focus on quality. We also listened to patients describe their experiences, and an added benefit of our analysis was that we often used the insight gained from these consultations in meetings with other patients and families. Participants were asked 22 questions, and there were 6 identifiable themes of greatest patient satisfaction.

Methods

The inpatient palliative care consult team consisted of a palliative care physician, a registered nurse, and a medical social worker. A clinical ethicist was available for support when ethical questions arose and advised us regarding implementation of the study design, analysis, and the drafting of the manuscript.

The inpatient palliative care consultation team recruited patients who had a treatment plan that had been reached by consensus. Data collection for our qualitative study continued until saturation. That is, we collected data and identified distinct, recurring themes or patterns until no new themes or patterns emerged. Our sample appears to be small, but it is not uncommon for qualitative studies to enroll fewer than 100 participants, because in grounded theory, n equals the number of themes or categories, not the number of individual participants.4

Our sample was made up of patients referred to the inpatient palliative care team for consultation with hospitalists, intensivists, and long-term care physicians about goals of treatment. During the consultation we spent time with patients and their families to learn more about their life experiences: we discussed the patient’s specific context for treatment planning; examined pain control; acknowledged cultural beliefs and values; provided a more thorough explanation of the trajectory of the illness; developed a patient-centered, realistic plan of action; and paid special attention to the complex and multiple aspects of human dignity. All respondents completed a questionnaire within one week following the inpatient palliative care consultation. Consent forms were obtained from all those who participated in the study. Subjects responded to the questionnaires with regard to their consultation as well as their previous experiences, thus the study was retrospective.

We found a distinct sampling pattern in the data from 25 inpatient palliative care consultations. We administered a 22-item questionnaire to patients and their families and analyzed their responses to characterize their previous experiences. This feedback helped us evaluate the quality of our inpatient palliative care consultations. Study participants had been referred to the in-patient palliative care consultation team for a goals-of-treatment consultation. All patients included in the study gave written, informed consent to participate. The questionnaire was approved by the KP Southern California institutional review board (R2010023; IRB# 5644).

Results

We collated the results from our questionnaire and identified patterns of quality associated with inpatient palliative care consultation.

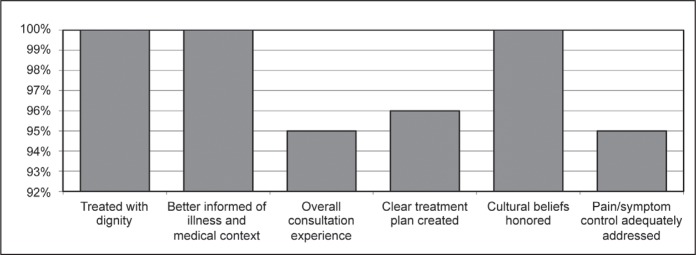

Figure 1 describes 6 patient satisfaction areas. All patients who responded felt they were treated with dignity and respect by the hospital health care team. After the life-care planning consultation, all patients felt they were better informed of their illness and medical context; 95% of all patients who responded felt their overall experience was excellent; all respondents felt the life-care planning consultation helped them form a treatment plan to carry out their wishes; all patients who responded believed their cultural beliefs and values were respected. In addition, all questionnaire respondents noted that the inpatient palliative care team adequately addressed pain and symptom control.

Figure 1.

Patient satisfaction in the six areas queried.

Discussion

Although the importance of inpatient palliative care consultation has been widely reported in the literature,5–9 this study showed that it is helpful to characterize satisfaction from the patient’s perspective. Information regarding patient satisfaction must be focused if it is to provide helpful insight into what patients value during palliative care consultation. In the course of our research, the consultation team became more adept at understanding details of the patients’ situations and improved their practice of guiding patients through decision making. Our study fell short in not characterizing patient dissatisfaction. This information would have been helpful and should be included in future studies.

Future investigations might also include a broader and more probing questionnaire, quantitative analysis, and a larger patient pool. We must continue to create more quantitative and qualitative tools of analysis that help us better understand our patients and assist them to succeed in shared decision making for their health care journey.

We were encouraged by our findings: the feedback from patients and families showed us we were effective, from their perspective, in helping them shape their treatment journey. It also emphasized where we could have been even more effective in improving our communication. Six areas of patient satisfaction from the patient’s perspective were identified. We also learned that we must remain vigilant in addressing pain and symptom control and take every opportunity to maintain and improve the excellent patient satisfaction trajectory we have established. This study has inspired us to improve our practice of inpatient palliative care consultation. We are further reminded that it is vital to budget ample time to reflect on patients’ care experience so as to remain effectively patient centered.

Acknowledgments

Leslie E Parker, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The Physician’s Duty

No other gift is greater than the gift of life! The patient may doubt his relatives, his sons and even his parents, but he has full faith in his physician. He gives himself up in the doctor’s hands and has no misgivings about him. Therefore, it is the physician’s duty to look after him as his own.

References

- 1.Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson C. The familiar foundation and the fuller sense: ethics consultation and narrative. Perm J. 2012 Spring;16(2):60–3. doi: 10.7812/tpp/11-150. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7812/TPP/11-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW, Smith TJ. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Aug 1;30(22):2715–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4564. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards L, Norse JM. Readme first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2007. pp. 159–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quill TE, Arnold R, Back AL. Discussing treatment preferences with patients who want “everything. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Sep 1;151(5):345–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-5-200909010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brody JE. Frank talk about care at life’s end [monograph on the Internet] New York, NY: The New York Times; 2010. Aug 23, [cited 2012 Nov 7]. Available from: www.nytimes.com/2010/08/24/health/24brod.html?_r=0. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pantilat SZ. Communicating with seriously ill patients: better words to say. JAMA. 2009 Mar 25;301(12):1279–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.396. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaldjian LC, Erekson ZD, Haberle TH, et al. Code status discussions and goals of care among hospitalised adults. J Med Ethics. 2009 Jun;35(6):338–42. doi: 10.1136/jme.2008.027854. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jme.2008.027854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson C, Chand P, Sortais J, Oloimooja J, Rembert G. Inpatient palliative care consults and the probability of hospital readmission. Perm J. 2011 Spring;15(2):48–51. doi: 10.7812/tpp/10-142. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7812/TPP/10-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]