Abstract

Introduction:

Kaiser Permanente Colorado is an integrated health care system that uses automatic reminder programs and reduces barriers to access preventive services, including financial barriers. Breast cancer screening rates have not improved during the last five years, and rates differ between subgroups: for example, black and Latina women have lower rates of mammography screening than other racial groups.

Methods:

We retrospectively evaluated data from 47,946 women age 52 to 69 years who had continuous membership for 24 months but had not undergone mammography. Poisson regression models estimated relative risk for the impact of self-identified race/ethnicity, socioeconomic characteristics, health status, and use of health care services on screening completion.

Results:

The distribution of race/ethnicity among unscreened women was 55.5% white, 7.0% Latina, and 3.7% black, but race/ethnicity data were missing for 29%. Of these, no record of race/ethnicity was available for 86.7%, and for 5.1%, the data request was recorded but the women declined to identify their race/ethnicity. Nonwhite ethnicity increased risk of screening failure if black, Latina, “other” (eg, American Indian), or missing race/ethnicity. Population-attributable risks were low for minorities compared with the group for whom race/ethnicity data was missing. A greater number of office visits in any setting was associated with greater likelihood of undergoing mammography. Women with missing race/ethnicity data had fewer visits and were less likely to have an identified primary care physician.

Conclusions:

Greater improvement in mammography screening rates could be achieved in our population by increasing screening among women with missing race/ethnicity data, rather than by targeting those who are known to be of racial/ethnic minorities. Efforts to address screening disparities have been refocused on inreach and outreach to our “missing women.”

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer deaths for US women, although improved access to screening and advances in treatment strategies have lowered breast cancer mortality.1 The US Preventive Services Task Force has recommended biennial mammography for women between 50 and 74 years of age.2 This grade B recommendation qualified mammography as a prevention benefit of the Patient Protection and Affordability Act3 and will decrease financial barriers to breast cancer screening. The US health system is preparing to expand coverage to currently uninsured women, but we anticipate that the impact of barriers besides lack of access and coverage will continue to undermine preventive screening efforts. Women with low socioeconomic status, uninsured status, and nonwhite race have in the past experienced inequities with respect to lack of awareness of the benefits of screening, access to care, and adverse outcomes.4–7 By better understanding those women who remain unscreened, despite being insured and actively encouraged to undergo screening, we can refocus our strategies for promoting preventive services.

In addition to access and coverage, socioeconomic issues, health status, use of health services, and social/cultural considerations have been identified as barriers to breast cancer screening. Lower breast cancer screening rates have been associated with nonwhite race, low level of education, and low socioeconomic status.6–10 Low income can counteract the advantage of otherwise good geographic access because it is associated with difficulties with transportation, child care, and work schedules.11 Women with health conditions such as disability,12 depression,13 and morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 40 kg/m2)14,15 are less likely to complete screening. Although women are more likely to have been screened if they have a family history of breast cancer9,16,17 or if they have ever had relevant symptoms or abnormal test results,11 screening may be perceived as less important for those without these risks. Not having a usual source of care, not having a primary care physician (PCP), and failing to engage in other health-promoting behaviors also predict unscreened status.9,10,16–18 In women of color, the decision to forgo screening may reflect distrust because of perceived disrespect of physicians.19 Among Latinas, cultural barriers such as fear, embarrassment, and a sense of fatalism have been linked to nonadherence to mammography recommendations.20 Health care delivery systems have actively addressed some of these factors with programs that facilitate bonding with a personal physician, educate care teams about diversity, and address common barriers. Despite such efforts, a cadre of women continues to forgo screening.

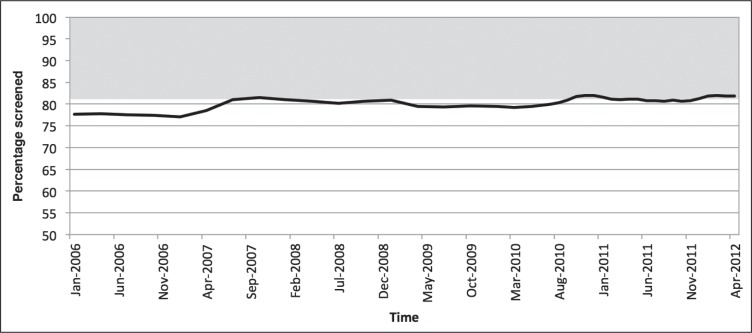

Kaiser Permanente (KP) Colorado (KPCO) is an integrated health care system that provides continuous access to care, preventive services for reduced copayment or no copayment, and systematic outreach and inreach programs. This article describes the characteristics of a large group of insured women who remained unscreened for breast cancer for more than 2 years. KPCO used outreach and inreach strategies validated in other multimodal programs21–24 to address common barriers and achieved mammography screening rates at the 80th percentile. But as Figure 1 indicates, screening rates have reached a plateau during the last 5 years. We focused on the approximately 20% of women who should have undergone screening but did not. We examined demographic and social characteristics, health status, and use of health care services in our insured population to identify characteristics associated with unscreened status. An internal Equitable Care Report in 2010 addressing disparities in effectiveness of care measures at KPCO showed that the rate of breast cancer screening was lower in black (73.3%) and Latina (73.4%) women compared with whites (78.2%) and all women (77.2%).25 We were therefore particularly interested in investigating the relationship between screening status and these newly collected data about self-identified race, ethnicity, and language preference (RELP). The purpose of this analysis was to identify opportunities for future quality-improvement initiatives to reach insured women who remain unscreened.

Figure 1.

Rate of Breast cancer screening in women aged 52 to 69 years, 2006–2012.

The increase in screening rate in 2007 was related to the initiation of radiology outreach calls to women overdue for screening. The gray area indicates the target population for this initiative.

Methods

Population of Interest and Data Sources

KPCO has more than 530,000 members. We evaluated data from 47,946 insured women age 52 to 69 years with continuous enrollment for the 24 months through July 2010, ie, women who had 2 years after turning 50 to complete mammography in our system. For this age group, the US Preventive Services Task Force has strongly recommended screening with mammography every 2 years.2 Women were considered unscreened if there was no report available of a completed mammogram during this time period. Data sources used to assess health status and use of health care services included KPCO’s electronic medical records; population registries tracking routine preventive care, including mammography screening; and chronic disease management programs. RELP data have been collected routinely during phone and office encounters since 2007 and were self-identified for approximately 70% of all members during the study period. Women were categorized as missing RELP data if their race/ethnicity was unknown to them (eg, in those who were adopted), if they declined to give this information, or if no RELP code was available for analysis. Demographic information from membership databases provided information about marital status and source of insurance (ie, commercial, Medicaid, or Medicare). The analysis was done in the context of quality-improvement efforts.

Breast Cancer Screening Program

The breast cancer screening program at KPCO included tracking mammography screening rates reported at the regional, office, and clinician levels; prompts to clinicians for members due or overdue for screening through the electronic medical record system; proactive outreach letters; as well as automated reminder calls to members. Inreach reminders at check-in for primary care or mental health services identified women due for screening. Beginning in 2007, personal outreach calls to overdue women were made twice a year through a centralized call center that offered the option of booking a radiology appointment during the call. Educational materials providing information about common fears and barriers and the importance of screening were available online and in offices, in both Spanish and English. Barriers addressed in educational materials included lack of knowledge regarding risk, fear of an abnormal result, pain, potential damage to implants, fear of radiation exposure, and inconvenience.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis was performed in mid-2010 with SAS 9.13 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC). We used Poisson regression models with robust error variance with screening as the dependent variable to estimate relative risk.26 Adjusted models included all the analysis variables. Secondary models looked at predictors of screening within the strata of black and Latina women. Differences in visit history, bonding, insurance status, and age were examined between those who were and were not missing RELP data.

Socioeconomic variables included age, race/ethnicity, language preference, marital status, and insurance type (commercial, Medicaid, or Medicare). Health status variables included smoking status and BMI. BMI was calculated in kg/m2 and tracked electronically. Another health status variable was presence of a chronic disease (asthma, coronary disease, kidney disease, depression, diabetes, and heart failure), as indicated by active enrollment in a chronic disease registry. Use of health care services was assessed on the basis of evidence of having selected a PCP and visit history in Primary Care, Obstetrics and Gynecology (OB/GYN), and other specialty departments within the last year. The contribution of individual variables to the screening population as a whole was evaluated by calculating the population-attributable risk as (relative risk [RR] - 1) / RR × proportion exposed population, where RR is the relative risk.27

Results

The population was predominately white (55.5%). Race and ethnicity data were missing for 29.0%, and the remaining members identified themselves as Latina (7.0%), black (3.7%), other (2.9%), or Asian (1.8%). Most of the population (59.9%) was between the ages of 55 and 64 years. The majority (79.7%) had commercial insurance, and none had dual eligibility (Medicaid and Medicare). All variables analyzed had significant univariate associations with screening status (p < 0.001), with the exception of chronic disease status: only depression and asthma were significantly associated with screening status (Table 1). Of the 13,926 women with missing race/ethnicity data, 329 (2.4%) had “unknown” race (for example because they had been adopted); 705 (5.1%) had declined to give this information; 816 (5.9%) responded but listed “other” as their category and the majority, 12,076 women (86.7%), had no RELP code captured.

Table 1.

Breast cancer screening within 24 months in women age 52 to 59 years

| Variable | N | Screened, n (%) | Unscreened, n (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 47,946 | 38,443 (80.2) | 9503 (19.8) | |

| Age, years | <0.001 | |||

| 52–54 | 9123 | 6985 (76.6) | 2138 (23.4) | |

| 55–59 | 15,332 | 12,012 (78.4) | 3320 (21.7) | |

| 60–64 | 13,383 | 10,854 (81.1) | 2529 (18.9) | |

| ≥65 | 10,108 | 8592 (85.0) | 1516 (15.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| Asian | 869 | 730 (84.0) | 139 (16.0) | |

| Black | 1776 | 1433 (80.7) | 343 (19.3) | |

| Latino | 3373 | 2731 (81.0) | 642 (19.0) | |

| Other | 1392 | 1100 (79.0) | 292 (21.0) | |

| Missing data | 13,926 | 9664 (69.4) | 4262 (30.6) | |

| White | 26,610 | 22,785 (85.6) | 3825 (14.4) | |

| Language preference | <0.001 | |||

| English | 40,542 | 34,096 (84.1) | 6446 (15.9) | |

| Other | 523 | 421 (80.5) | 102 (19.5) | |

| Spanish | 447 | 376 (84.1) | 71 (15.9) | |

| Missing data | 6434 | 3550 (55.2) | 2884 (44.8) | |

| Insurance | <0.001 | |||

| Commercial | 38,221 | 30,168 (78.9) | 8053 (21.1) | |

| Medicaid | 76 | 52 (68.4) | 24 (31.6) | |

| Medicare | 9649 | 8223 (85.2) | 1426 (14.8) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married/partner | 28,638 | 24,279 (84.8) | 4359 (15.2) | |

| Div/sep/widowed | 6106 | 5017 (82.2) | 1089 (17.8) | |

| Single | 7837 | 6241 (79.6) | 1596 (20.4) | |

| Missing data | 5365 | 2906 (54.2) | 2459 (45.8) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | <0.001 | |||

| <18.5 | 592 | 433 (73.1) | 159 (26.9) | |

| 18.5–24 | 14,263 | 11,959 (83.9) | 2304 (16.2) | |

| 25–29.9 | 14,433 | 12,011 (83.2) | 2422 (16.8) | |

| 30–39.9 | 13,685 | 11,125 (81.3) | 2560 (18.7) | |

| ≥40 | 3365 | 2527 (75.1) | 838 (24.9) | |

| Missing data | 1608 | 388 (24.1) | 1220 (75.9) | |

| Smoking | <0.001 | |||

| Current smoker | 5181 | 3433 (66.3) | 1748 (33.7) | |

| Former smoker | 14,468 | 12,104 (83.7) | 2364 (16.3) | |

| Nonsmoker | 27,164 | 22,583 (83.1) | 4581 (16.9) | |

| Missing data | 1133 | 323 (28.5) | 810 (71.5) | |

| Asthma | <0.001 | |||

| No | 41,058 | 32,704 (79.7) | 8354 (20.4) | |

| Yes | 6888 | 5739 (83.3) | 1149 (16.7) | |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.119 | |||

| No | 46,514 | 37,318 (80.2) | 9196 (19.8) | |

| Yes | 1432 | 1125 (78.6) | 307 (21.4) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.219 | |||

| No | 46,804 | 37,511 (80.1) | 9293 (19.9) | |

| Yes | 1142 | 932 (81.6) | 210 (18.4) | |

| Depression | <0.001 | |||

| No | 38,677 | 30,809 (79.7) | 7868 (20.3) | |

| Yes | 9269 | 7634 (82.4) | 1635 (17.6) | |

| Diabetes | 0.589 | |||

| No | 42,923 | 34,430 (80.2) | 8493 (19.8) | |

| Yes | 5023 | 4013 (79.9) | 1010 (20.1) | |

| Heart failure | 0.015 | |||

| No | 47,266 | 37,923 (80.2) | 9343 (19.8) | |

| Yes | 680 | 520 (76.5) | 160 (23.5) | |

| Primary care physician bond | <0.001 | |||

| No | 873 | 595 (68.2) | 278 (31.8) | |

| Yes | 47,073 | 37,848 (80.4) | 9225 (19.6) | |

| Primary care encounters last year, n | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 2.1±2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | |

| 0 Primary care encounters | 10,464 | 6603 (63.1) | 3861 (36.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 Primary care encounters | 37,482 | 31,840 (84.9) | 5642 (15.1) | |

| OB/GYN encounters last year, n | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.3±0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | |

| 0 OB/GYN encounters | 39,136 | 30,193 (77.2) | 8943 (22.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 OB/GYN encounters | 8810 | 8250 (93.6) | 560 (6.4) | |

| Specialty encounters last year, n | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 5.0 | 4.1 ± 5.1 | 1.9 ± 4.2 | |

| 0 Specialty encounters | 9819 | 4831 (49.2) | 4988 (50.8) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 Specialty encounters | 38,127 | 33,612 (88.2) | 4515 (11.8) | |

BMI = body mass index; div = divorced; OB/GYN = obstetrics/gynecology; SD = standard deviation; sep = separated.

Although women can request and undergo mammography screening without an office visit, those with more office visits in any setting were more likely to have been screened … Younger women were more likely to be missing race/ethnicity data …

Adjusted relative risk estimates and results of population-attributable risk calculations are shown in Table 2. Women were more likely to be unscreened if they were younger than the comparison group (ie, younger than 65 years). Women who were not married were also more likely to be unscreened. Women insured through Medicaid were less likely to be screened, compared with members with commercial coverage. A lower screening rate was not evident among women insured through Medicare. With respect to health status, current smokers were more likely to be unscreened than nonsmokers, and women with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 or <18.5 kg/m2 were more likely to be unscreened. The greatest chronic disease impact was for those with heart disease or heart failure. Evaluation of use of health care services showed that the likelihood of completing screening progressively increased with the number of office visits in Primary Care, OB/GYN, or other specialty departments.

Table 2.

Relative risks from adjusted model and population-attributable fraction

| Variable | Relative risk (95% CI) | Proportion of cases with factor | Population-attributable fraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 52–54 | 1.26 (1.17, 1.37) | 0.225 | 0.05 |

| 55–59 | 1.18 (1.09, 1.27) | 0.349 | 0.05 |

| 60–64 | 1.11 (1.02, 1.20) | 0.266 | 0.03 |

| ≥65 | referent | 0.16 | |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 1.05 (0.90, 1.24) | 0.068 | 0.00 |

| Black | 1.22 (1.11, 1.33) | 0.036 | 0.01 |

| Latino | 1.24 (1.15, 1.33) | 0.002 | 0.00 |

| Other | 1.33 (1.21, 1.47) | 0.031 | 0.01 |

| Missing data | 1.28 (1.22, 1.34) | 0.448 | 0.10 |

| White | referent | 0.403 | |

| Language preference | |||

| Spanish | 0.77 (0.63, 0.95) | 0.068 | −0.02 |

| Other | 1.22 (1.03, 1.46) | 0.036 | 0.01 |

| Missing data | 1.17 (1.11, 1.24) | 0.031 | 0.00 |

| English | referent | 0.846 | |

| Smoking | |||

| Current smoker | 1.53 (1.46, 1.60) | 0.184 | 0.06 |

| Former smoker | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10) | 0.249 | 0.01 |

| Missing data | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.085 | 0.00 |

| Nonsmoker | referent | 0.567 | |

| Insurance | |||

| Medicare | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.002 | 0.00 |

| Medicaid | 1.36 (0.98, 1.89) | 0.200 | 0.05 |

| Commercial | referent | 0.797 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Divorced/widowed | 1.14 (1.08, 1.21) | 0.127 | 0.02 |

| Single | 1.22 (1.16, 1.28) | 0.163 | 0.03 |

| Missing data | 1.25 (1.20, 1.31) | 0.112 | 0.02 |

| Married | referent | 0.597 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||

| <18.5 | 1.42 (1.26, 1.62) | 0.012 | 0.00 |

| 25–29 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 0.301 | 0.01 |

| 30–39 | 1.09 (1.04, 1.15) | 0.285 | 0.02 |

| ≥40 | 1.40 (1.31, 1.49) | 0.070 | 0.02 |

| Missing data | 1.46 (1.37, 1.56) | 0.034 | 0.01 |

| 18.5–24 | referent | 0.297 | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Asthma | 1.04 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.144 | 0.00 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.30 (1.18, 1.44) | 0.039 | 0.01 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.15 (1.02, 1.30) | 0.024 | 0.00 |

| Depression | 1.11 (1.06, 1.17) | 0.193 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes | 1.14 (1.08, 1.21) | 0.105 | 0.01 |

| Heart failure | 1.44 (1.25, 1.66) | 0.014 | 0.00 |

| Primary care physician bonding | |||

| No | 1.22 (1.11, 1.34) | 0.018 | 0.00 |

| Primary care encounters last year, n | |||

| ≥11 | 0.78 (0.54, 1.12) | 0.050 | −0.01 |

| 6–10 | 0.93 (0.83, 1.05) | 0.046 | 0.00 |

| 4–5 | 0.80 (0.73, 0.87) | 0.103 | −0.03 |

| 2–3 | 0.79 (0.75, 0.84) | 0.327 | −0.09 |

| 1 | 0.81 (0.78, 0.85) | 0.302 | −0.07 |

| 0 | 0.218 | ||

| OB/GYN encounters last year, n | |||

| ≥4 | 0.34 (0.20, 0.57) | 0.060 | −0.12 |

| 2–3 | 0.42 (0.34, 0.50) | 0.031 | −0.04 |

| 1 | 0.41 (0.38, 0.45) | 0.147 | −0.21 |

| 0 | 0.816 | ||

| Other encounters last year, n | |||

| ≥11 | 0.27 (0.24, 0.30) | 0.075 | −0.20 |

| 6–10 | 0.27 (0.25, 0.30) | 0.126 | −0.33 |

| 4–5 | 0.28 (0.26, 0.30) | 0.127 | −0.33 |

| 2–3 | 0.32 (0.30, 0.34) | 0.258 | −0.55 |

| 1 | 0.43, (0.41, 0.46) | 0.210 | −0.27 |

| 0 | 0.205 | ||

CI = confidence interval; OB/GYN = obstetrics/gynecology.

Self-identified nonwhite ethnicity increased risk of being unscreened for black, Latino, and “other” (eg, American Indian) members and for those with missing race/ethnicity data, but not for Asians. Women who identified themselves as Spanish speakers were more likely to have undergone screening than English speakers. Stratified models looking at associations between different variables and screening behavior in black and Latina women did not suggest differences in the impact of health variables such as smoking or BMI in these populations (data not shown). Despite increased relative risks for most nonwhite women (except Asians) compared with whites, population-attributable risks for the nonwhite race categories were relatively low (0.01). Of greater impact than nonwhite race was missing race/ethnicity data, which had a population-attributable risk of 0.10.

Women with missing race/ethnicity data had evidence of some use of the system, but on average they used it less than those whose data were complete. Although nearly all women were bonded with a PCP, those with missing race were more likely to be unbonded (3.17%) compared with those with race data (1.27%) (p < 0.001). Among those with missing race/ethnicity data, 33.2% had had no primary care visits, compared with 17.2% of those whose race/ethnicity data were recorded (p < 0.001). Regarding all office visits (including primary care visits), 18.8% of women with missing race/ethnicity data had had no clinic visits during the study period, compared with 5.95% of women with complete race/ethnicity data. Younger women were more likely to be missing race/ethnicity data, but there was no clear pattern based on insurance status.

Discussion

In our population, greater improvement in mammography screening rates could be achieved by increasing screening among those women who have missing race/ethnicity data than by efforts targeted at those known to be racial/ethnic minorities. Women who identified Spanish as their preferred language were more likely to have been screened, suggesting that lack of acculturation itself was not a barrier. Because self-identified race/ethnicity data have been routinely collected during office visits and phone communication since 2007, its absence suggests less use of the care delivery system. Women whose records were missing this information had lower rates of bonding and had fewer office contacts compared with those whose records included this information. Although women can request and undergo mammography screening without an office visit, those with more office visits in any setting were more likely to have been screened, suggesting that the factors driving failure to have an office visit may also hinder proactive health promoting behavior, independent of office-based care. In our analysis, even when we controlled for other variables associated with low participation in preventive screening, such as Medicaid insurance coverage, active smoking, and obesity, the dominant impact of missing race/ethnicity data persists.

A 2006 systematic review of 114 articles about disparities research using administrative and secondary data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) investigated the effect of missing race/ethnicity data on potential study bias.28 Although missing race/ethnicity data were common, more than 40% of the studies either did not discuss or quantify missing race/ethnicity data, even when such data were the primary focus of the research question. The data that were available were usually correct. The authors noted that the absence of race/ethnicity data in administrative data not from the VHA (such as Medicare) is frequently nonrandom, with higher rates among minorities, and that this was also true of the VHA databases. When the total membership in KPCO is examined at a population level, members without self-reported race/ethnicity data appear to have a similar race/ethnicity distribution as members whose records do contain these data. (See Table 3. The data in Table 3 were gathered from an unpublished report provided by the Center for Healthcare Analytics at KP that includes imputed race/ethnicity based on geographic coding and surname analysis for members without self-reported race/ethnicity data.) However, in the subset of women in our study population who are both unscreened and missing race/ethnicity data, there may actually be a higher proportion of minority women who are not identified and are missing data caused by issues related to their minority status; this could be an area of further analysis.

Table 3:

Self-reported and imputed race/ethnicity

| Data source | Race/ethnicity distribution, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whitea | Black or African Americana | Hispanic or Latino | Asian or Pacific Islandera | American Indian or Alaskan Nativea | Multiracial | |

| Self-reported | 74.4 | 4.9 | 15.3 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| Imputed (if missing self-reported data) | 73.2 | 4.4 | 16.9 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| Combined self-reported and imputed data | 74.0 | 4.8 | 15.8 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

Ethnicity = non-Hispanic.

Our study cannot demonstrate the reason for the association between missing race/ethnicity data and screening status. Women with missing race/ethnicity data had an even higher probability of being unscreened than women known to be of a minority race and seemed to have relatively less contact with our care delivery system. Our results cannot be generalized to uninsured women, because continuous coverage at least for 2 years was a prerequisite for inclusion in this analysis. The unscreened women who had relatively less contact with our delivery system may include a small number who had secondary insurance and obtained care elsewhere. If women are undergoing screening at KP arranged independent of any office contact, they are likely to be few in number. A qualitative assessment of women very overdue (by at least 4 years, N = 169 respondents) for screening, done by KP Northern California in 2009,29 found that only 7% of respondents had had a mammogram outside of KP. The most common barriers identified in responses to a survey questionnaire were related to pain (38.5% of respondents), perception of low risk (28.4%), and concern about repeated radiation exposure (26.6%). Further, 37.8% of respondents did not want to get a mammogram, “no matter what.” We do not know the socioeconomic status or level of education of those for whom we are missing data, and we suspect that these variables likely affect their willingness and capacity to obtain preventive services.

Population-based approaches using phone or mail to reach out to those who have already refused preventive services can be resource intensive and ineffective.30 Our breast cancer screening program includes educational materials to address common barriers and a strategy of outreach calls from a centralized call center. The result was an initial improvement in 2007, but increases in screening rates did not continue (Figure 1). A subset of women have made an informed decision not to undergo screening. The results of the analysis reported here have encouraged us to scale back initiatives targeting racial/ethnic groups and to focus instead on collaborating across outreach programs to build relationships with women with low use of our health services. Our current strategy is to “engage the unengaged” in any setting: mammography inreach occurs during nonprimary care contact, including visits to dieticians, mental health professionals, and other specialists. Office and call center staff are being trained to assess readiness to change using motivational interviewing. PCPs call women in their panel who are overdue by 3 years for mammography for a personal discussion regarding screening. During these calls, physicians can address individual barriers, and women who make an informed decision against screening are excluded from future outreach. Unscreened women who are not bonded to a PCP receive a personal call from the team dedicated to women’s preventive services to assist them in choosing a PCP and to address gaps in preventive care, including mammography. New members, many of whom may delay making their first appointment, receive personalized guidebooks that link them to Web-based guidelines for screenings, including mammograms.

Although this study has helped us to refocus our efforts to reach unscreened women, it has also raised provocative questions about the meaning of missing race/ethnicity data as well as the potential utility of this lens for examining other aspects of health care inequity. Even as we continue to reach out to those who, although insured, do not fully participate in preventive care, we need to improve our understanding of the causes, which can be subtle and complex, of health care disparities.

Acknowledgments

Leslie Parker, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

A Palliative Course

Mme de Montigny … had a cancer the size of a nut in the left breast … .

[Houllier] considered the tumor to be cancerous and we decided upon a palliative course, fearing to irritate this Hydra, and cause it to burst in fury from its lair.

He ordered … certain purgations … and on the tumor was placed a sheet of lead covered with quick-silver … . A more aggressive treatment … terminated with ulceration … . The heart failed and death followed.

— Ambroise Paré, c 1510 – 1590, French barber surgeon to Henry II, Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III, considered one of the fathers of surgery and modern forensic pathology, and a pioneer in battlefield medicine

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: breast cancer screening among women aged 50–74 years—United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Jul 9;59(26):813–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Nov 17;151(10):716–26. W-236. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. Erratum in: Ann Intern Med 2012 May 18;152(10):688; Ann Intern Med 2010 Feb 2;152(3):199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preventive services covered under the Affordable Care Act [monograph on the Internet] Washington, DC: HealthCare.gov; Updated 2012 Sep 27 [cited 2012 Nov 24]. Available from: www.healthcare.gov/news/fact-sheets/2010/07/preventive-services-list.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byers TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the United States: findings from the National Program of Cancer Registries Patterns of Care Study. Cancer. 2008 Aug 1;113(3):582–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23567. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, et al. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes CA Cancer J Clin 2008January–Feb5819–31.DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3322/CA.2007.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayanian JZ, Kohler BA, Abe T, Epstein AM. The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer. N Eng J Med. 1993 Jul 29;329(5):326–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290507. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199307293290507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez MA, Ward LM, Pérez-Stable EJ.Breast and cervical cancer screening: impact of health insurance status, ethnicity, and nativity of Latinas Ann Fam Med 2005May–Jun33235–41.DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1370/afm.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells KJ, Roetzheim RG. Health disparities in receipt of screening mammography in Latinas: a critical review of recent literature. Cancer Control. 2007 Oct;14(4):369–79. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borrayo EA, Hines L, Byers T, et al. Characteristics associated with mammography screening among both Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009 Oct;18(10):1585–94. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1009. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2008.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selvin E, Brett KM. Breast and cervical cancer screening: Sociodemographic predictors among white, black, and Hispanic women. Am J Pub Health. 2003 Apr;93(4):618–23. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogedegbe G, Cassells AN, Robinson CM, et al. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators of cancer early detection among low-income minority women in community health centers. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Feb;97(2):162–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez A, Farmer GC, Grant D, Papachristou T. Disability and preventive cancer screening: results from the 2001 California Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 2005 Nov;95(11):2057–64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066118. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.066118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludman EJ, Ichikawa LE, Simon GE, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening: specific effects of depression and obesity. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Mar;38(3):303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.039. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Crabtree BF, Wartenberg D. Cancer screening in women: body mass index and adherence to physician recommendations. Am J Prev Med. 2007 Jun;32(6):525–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.004. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruthur NM, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Clark JM. Obesity and mammography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 May;24(5):665–77. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0939-3. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-0939-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Achat H, Close G, Taylor R. Who has regular mammograms? Effects of knowledge, beliefs, socioeconomic status, and health-related factors. Prev Med. 2005 Jul;41(1):312–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.016. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah M, Zhu K, Palmer RC, Jatoi I, Shriver C, Wu H. Breast, colorectal, and skin cancer screening practices and family history of cancer in US women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007 May;16(4):526–34. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0108. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackwell DL, Martinez ME, Gentleman JF.Women’s compliance with public health guidelines for mammograms and Pap tests in Canada and the United States: an analysis of data from the Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health Womens Health Issues 2008March–Apr18285–99.DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2007.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peek ME, Sayad JV, Markwardt R. Fear, fatalism and breast cancer screening in low-income African-American women: the role of clinicians and the health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Nov;23(11):1847–53. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0756-0. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0756-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauaia A, Min SJ, Lack D, et al. Church-based breast cancer screening education: impact of two approaches on Latinas enrolled in public and private health insurance plans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007 Oct;4(4):A99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valanis B, Whitlock EE, Mullooly J, et al. Screening rarely screened women: time-to-service and 24-month outcomes of tailored interventions. Prev Med. 2003 Nov;37(5):442–50. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00165-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeFrank JT, Rimer BK, Gierisch JM, Bowling JM, Farrell D, Skinner CS. Impact of mailed and automated telephone reminders on receipt of repeat mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Jun;36(6):459–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.032. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonfill X, Marzo M, Pladevall M, Martí J, Emparanza JI. Strategies for increasing the participation of women in community breast cancer screening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD002943. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002943. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldstein AC, Perrin N, Rosales AG, et al. Effect of a multimodal reminder program on repeat mammogram screening. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Aug;37(2):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.022. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Platt ST. Special equitable care report for the Colorado region [unpublished report] Oakland, CA: Kaiser Foundation Health Plan Center for Healthcare Analytics; 2011. [cited 2012 Jun 1] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr 1;159(7):702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health. 1998 Jan;88(1):15–19. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.15. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.1.15 Erratum in: Am J Public Health 2008 Dec;98(12):2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long JA, Bamba MI, Ling B, Shea JA. Missing race/ethnicity data in Veterans Health Administration based disparities research: a systematic review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006 Feb;17(1):128–40. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0029. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2006.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon NP. Why women don’t come in for breast cancer screening: results of a survey of Kaiser Permanente members very overdue for mammograms [monograph on the Internet] Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente Division of Research; 2009. Dec 3, [cited 2012 Jun 1]. Available from: www.dor.kaiser.org/external/why_no_mammogram/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Persell SD, Friesema EM, Dolan NC, Thompson JA, Kaiser D, Baker DW. Effects of standardized outreach for patients refusing preventive services: a quasiexperimental quality improvement study. Am J Manag Care. 2011 Jul 1;17(7):e249–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]