Abstract

This article proposes transprocessing (as in “transduction” and “processing”) as a term to denote mechanisms by which the brain processes information in psychotherapy and develops solutions that have a lasting, curative effect. The case of a woman with a history of posttraumatic conversions, who recovered after long-term psychotherapy, is presented as the basis for a discussion on psychotherapeutic changes of the brain. Psychological healing and change, in general, is seen here as a result of a large variety of neurobiologic processes that reframe complex or multimodal memories. Through transprocessing, multimodal memories are deconstructed along the different axes of the brain tissue and restored through memory mechanisms at the synaptic, cellular level. Transprocessing requires a sustained interplay between the extended projections of the “language brain” and the repeated, alternating activation and deactivation of the midline structures associated with the self, to form pathways through long-term therapeutic experiences. We propose three separate stages of transprocessing by which new implicit and explicit memories of the therapeutic narrative are internalized into a first-person experience. Those stages are 1) evaluation, 2) acquisition, and 3) contextualization.

Introduction

Despite rapid advances in neurosciences, the neurologic basis for changes facilitated by psychotherapy remains unclear. The following case report introduces a discussion of newer findings regarding information processing and learning during psychotherapy.

Proposal

This article proposes transprocessing (as in transduction and processing) as a term to denote mechanisms by which the brain processes information in psychotherapy and the patient develops solutions that have a lasting, curative effect. Psychological healing and change, in general, are seen here as a result of a large variety of neurobiologic processes that reframe complex or multimodal memories. Through transprocessing, multimodal memories are deconstructed along the different axes of the brain tissue and restored through memory mechanisms at the synaptic, cellular level. Transprocessing requires a sustained interplay between the extended projections of the “language brain” and the repeated activation and deactivation of the midline structures associated with the self, to form pathways through long-term therapeutic experiences. We propose three separate stages of transprocessing by which new implicit and explicit memories of the therapeutic narrative are internalized as first-person experiences.

Case Report

A woman, age 44 years, was referred by a local internist after progressive speech problems and labile affect developed. Findings of the initial examination revealed a history of postpartum depression at age 34 years. At that time, with medication treatment and a 2-year course of psychoanalytic psychotherapy, the patient showed a full recovery.

On examination, the most striking finding was labile affect in the form of brief attacks of dysphoria, which were immediately relieved after changing the subject of conversation.

The patient’s speech pattern was that of dysfluent aphasia. She was able to name objects and say nouns correctly. She was also alert and showed good nonverbal communication. Yet, she was unable to speak in full sentences. She was also speaking in a hoarse voice, which according to her husband, she had never before presented. At home she was irritable and would burst into brief crying spells. She had a recurrence of old nightmares, which we later learned were related to trauma. The rest of the neurologic findings and the results of the magnetic resonance image were normal. Further history revealed that she had been a flight attendant and had been assaulted and raped while walking to her hotel during a layover abroad 15 years previously. She had never received any treatment related to the rape.

She did well until she gave birth to her first daughter ten years before her referral to us, when she developed postpartum depression. During this episode she did not tolerate medications. Working diagnoses of conversion disorder and major depression with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was made.

The patient was seen in dynamic psychotherapy 3 times per week. During interpretations that were rated as essential to autobiography, labile affect worsened temporarily by triggering a catastrophic reaction: a sudden attack of crying, lasting between 20 seconds and 1 minute. This was followed by a smile. The succession between states was dramatic. After about 12 weeks of treatment consisting of 36 sessions, the affect became more stable. She was able to focus on her emotional state, elaborating on it as her facial expressions became more congruent with her internal state. On numerous occasions, when the orbicularis oris muscles contracted and pulled her mouth downward into a sad expression, she would be able to connect to emotions of sadness.

During the following 50 sessions (approximately 3 months), the patient spent most of the time during her sessions talking at length about her deep feelings of loss and her belief that she had suffered a stroke. She was experiencing a sense of lack of control over the future. During the same time, she experienced nightmares and severe nocturnal anxiety. She reported nightmares 2 to 3 times per week and exhibited symptoms of PTSD. She had hyperarousal in the form of attacks of anxiety with palpitations and headaches, which were diagnosed as tension headaches. The nightmares were eventually interpreted by her and by her therapist as expressions of fear of failure in life, which was tied to the emphasis her immigrant parents placed on academic performance. “It is easy to fail in America,” her mother used to say. “What if I fail?” had been part of her self-talk since adolescence. During psychotherapy new narratives of self-confidence developed, such as “I was actually privileged … .” It was later that she tied her sense of loss (eg, symptoms of stroke) to a perceived failure to foresee and prevent the rape. She saw herself as paralyzed in front of evil.

During the next six months, the nightmares gradually subsided. What was particular to this patient was a gradual improvement in her speech in parallel with the disappearance of nightmares. She returned to work full time after a year on sick leave.

Her depression lifted gradually, and she returned to old hobbies and interests. She became more involved with her two children and later decided to work half time so as to spend more time with her family. To date, four years since the episode, she has not shown any relapse of symptoms.

Discussion

On the basis of this case and the existing vast literature on psychological processing, we propose two areas for future exploration pertinent to the healing mechanisms in psychoanalytical psychotherapy: the neuroanatomical basis of processing and transprocessing and the uploading of implicit healing narratives.

Neuroanatomical Basis of Processing

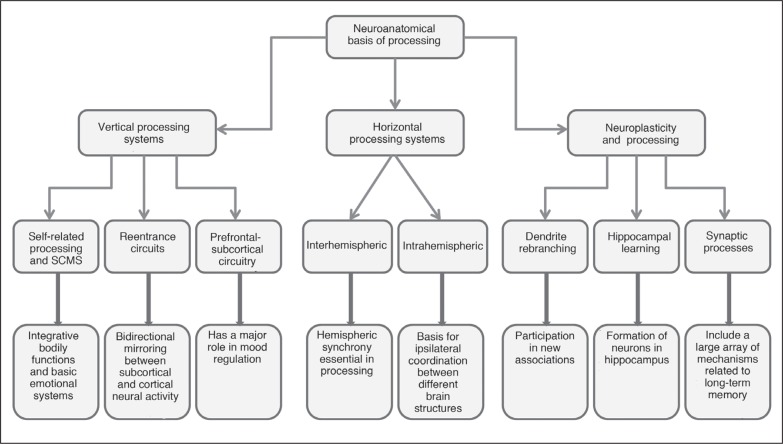

The large amount of literature on the neuroanatomical basis of processing mechanisms (Figure 1) divides it into vertical processing systems, horizontal processing systems, and neuroplasticity and processing.

Figure 1.

Neuroanatomical basis of processing.

SCMS = subcortical-cortical midline system.

Vertical processing systems: The vertical processing systems include:

self-related processing and the subcortical-cortical midline system

reentry circuits

prefrontal-subcortical circuitry.

Panksepp and Northoff1 have referred to self-related processing attributed to a set of midline structures that start in the brain stem, in the reticular activating system, and are interconnected with higher brain structures in the subcortical and cortical areas, referred to as the subcortical-cortical midline system. These structures accomplish the integrative bodily functions and the convergence of basic emotional systems to form the proposed “bodily self or proto-self”2–10 (see Sidebar Self-Related Processing and Subcortical-Cortical Midline System, item 1).

Self-Related Processing and Subcortical-Cortical Midline System.

Self-Related Processing and Subcortical-Cortical Midline System: The subcortical-cortical midline system includes the periaqueductal gray, an extremely rich connected brain structure,1 and the superior colliculi, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, ventral tegmental area, mesencephalic locomotor regions, preoptic areas, hypothalamus, and dorsomedial thalamus.2–4 Vertical processing also creates an access pathway between cortex, the prefrontal cortex, and brain-stem areas that are believed to generate the basic affective states (Seeking, Fear, Rage, Panic, Nurture, Lust, and Play) that are necessary for survival.2,5

Prefrontal Cortex: A detailed review of these networks is beyond this presentation but can be found in Price and Drevets.6 The subdivisions of the lateral and orbital medial prefrontal cortex (dorsal prefrontal, ventral prefrontal, caudal prefrontal, orbital and medial networks) cover, to different degrees, most aspects of human mental activity.

Interhemispheric Components: Clinical experience suggests it is the hemispheric synchrony that is created through the massive white-matter network essential in processing. A developmental right to left shift in hemispheric control and dominance in learning has been recognized.7 In the learning process, a dynamic shift in time occurs from task-naive to task-experienced recognition.8,9 Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder activate predominantly the right hemisphere during remembering and reexperiencing of trauma. This is unlike people who do not have posttraumatic stress disorder, who have left-brain dominance on brain imaging and evoked potentials. The experience of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing has further suggested a particular healing quality of processing that involves bilateral but alternative speech and brain stimulation. Furthermore, patients with a history of chronic trauma and alexithymia are known to have limited awareness of and/or access to their emotional experiences, with a high prevalence of somatization. Alexithymia and a history of early trauma have been associated with functional and anatomical deficits of the interhemispheric white matter.10–12 Traumatic memories and posttraumatic stress reconfigure a right-brain dominance due to catecholamine overconsolidation13 of memories in right hemispheric tracts early,14,15 before reaching the perceptive speech brain. Language is described as providing our subjective perception of being able to think.16 By means of the interhemispherical (transcallosal) transfer, information reaches the speech center, which exerts its role in awareness formation. Speech, through words, designs meaning to objects. It decreases emotional charge by diminishing the “incomprehensible” and unpredictable aspects of the environment. Unlike the earlier understanding of speech assigned to left speech centers only, the large, bilaterally extended notion of the “speech brain”17,18 refers to more global (evolutionary) networks of awareness and communication combined.

References

- 1.Strehler BL. Where is the self? A neuroanatomical theory of consciousness. Synapse. 1991 Jan;7(1):44–91. doi: 10.1002/syn.890070105. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/syn.890070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panksepp J. The periconscious substrate of consciousness: affective states and the evolutionary origins of the self. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 1998;5(5–6):566–82. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panksepp J. Affective neuroscience: the foundations of human and animal emotions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, USA; 1998. Aug 15, [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holstege G, Bandler R, Saper CB, editors. Progress in brain research: the emotional motor system. Vol. 107. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers, BV; 1996. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watt D. Consciousness and emotions: review of Jaak Panksepp’s “Affective Neuroscience. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 1999;6(6–7):191–200. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price JL, Drevets WC. Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010 Jan;35(1):192–216. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.104. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg E, Podell K, Lovell M. Lateralization of frontal lobe functions and cognitive novelty. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994 Fall;6(4):371–8. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bever TG, Chiarello RJ. Cerebral dominance in musicians and nonmusicians. Science. 1974 Aug 9;185(4150):537–9. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4150.537. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4150.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson PR. Dichotically-stimulated ear differences in musicians and nonmusicians. Cortex. 1977 Dec;13(4):385–9. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(77)80019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teicher MH, Samson JA, Sheu YS, Polcari A, McGreenery CE. Hurtful words: association of exposure to peer verbal abuse with elevated psychiatric symptom scores and corpus callosum abnormalities. Am J Psychiatry. 2010 Dec;167(12):1464–71. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010030. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010030 Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry 2011 Feb;168(2):213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teicher MH, Dumont NL, Ito Y, Vaituzis C, Giedd JN, Andersen SL. Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol Psychiatry. 2004 Jul 15;56(2):80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.016. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoppe KD. Hemispheric specialization and creativity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1988 Sep;11(3):303–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGaugh JL. Preserving the presence of the past. Hormonal influences on memory storage. Am Psychol. 1983 Feb;38(2):161–74. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.38.2.161. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.38.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitman RK, Shin LM, Rauch SL. Investigating the pathogenesis of posttraumatic stress disorder with neuroimaging. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 17):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hull AM. Neuroimaging findings in post-traumatic stress disorder. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002 Aug;181:102–10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.2.102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan-Solmes K, Solms M. Clinical studies in neuropsychoanalysis: introduction to a depth neuropsychology. 2nd ed. London: Karnak Books Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickok G, Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: a framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004 May-Jun;(1–2):92. 67–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickok G, Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 May;8(5):393–402. doi: 10.1038/nrn2113. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrn2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reentry, or the cortical-subcortical parallel reentrant circuits11–13 provide the structural basis for an interactive system, between the cortex and the subcortical areas of the basal ganglia and striatum, substantia innominata, and the extended amygdala. This network allows for a bidirectional mirroring between subcortical implicit networks and cortical neural activity.

The prefrontal cortex includes the orbital medial prefrontal cortex and the lateral prefrontal cortex and their connections to the striatum and to the thalamic nuclei. These very dense networks provide a major role in mood regulation (see Sidebar Self-Related Processing and Subcortical-Cortical Midline System, item 2).

Horizontal processing systems: These systems can be subclassified into the interhemispheric and intrahemispheric systems. The interhemispheric components include the corpus callosum and the anterior commissures. Routine conscious speech-driven activity maintains left-brain dominance. For psychotherapy and personal development, developing meaningful narratives about adverse life events have a healing quality.14 A large body of literature has further demonstrated that speech, in an interactional context, involves extended bilateral areas,15–26 which creates a “beltway of communication and awareness” around the entire brain (see Sidebar Self-Related Processing and Subcortical-Cortical Midline System, item 3).

Intrahemispheric processing occurs by means of the white matter tracts that are the structural basis for ipsilateral coordination between different brain structures. Such white matter structures are the inferior occipitofrontal fasciculus and the inferior longitudinal fasciculus.27 The role of these structures has been grossly overlooked in the past.

Neuroplasticity systems: This is a very extensive subject that involves learning processes and human change. Experiential relearning after brain damage has been shown to result in remapping of brain projections.28 Three major areas are of particular interest.

Dendrite rebranching, which includes the formation of new dendritic spines and their participation in new associations

Hippocampal learning and neurogenesis, referring to the formation of neurons in the hippocampus

Synaptic processes, which include a large array of long-term memory-related mechanisms, including protein synthesis, cytoskeletal reorganization, activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor,29–31 and possible epigenetic mechanisms. New multimodal memories are formed both by “new memory acquisition”32 and by a reworking of old memories at the time of “remembering,” a process referred to as “reconsolidation.”33

Transprocessing and Uploading of Implicit Healing Contents

In the case presented herein, activation of language, in time, led to an end of her speech abnormalities. Although the speech abnormality was highly suggestive of a neurovascular abnormality, the possibility of a minor cardiovascular anomaly, the lack of any abnormal findings on imaging, the lack of previous cardiovascular risk factors and relevant family history, and the positive history of psychological trauma strongly suggest conversion.

Because of a lack of clear neurologic pathology, conversion disorder was presumed to be the result of an underlying psychological mechanism, with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision) classifying it as a somatoform disorder34 and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision,35 classifying it as a dissociative disorder. Psychiatric treatment36 including psychotherapy37,38 and pharmacotherapy,39 hypnotherapy,40 and transcranial magnetic stimulation39 have all been proposed as methods of treatment for conversion disorder. Neuroanatomically, healing mechanisms involve complex changes in brain functioning. We propose the term transprocessing, a combination of two terms: transduction, meaning a reexpression and translation of a persistent functional brain activity into a new type of cellular activity (eg, transduction of stress in the function of the hypothalamopituitary axis), and processing, which is a function by which the brain makes sense of environmental inputs. The exact sequence of brain events in transprocessing during psychotherapy remains unclear at this time. However, several stages in the course of changes during long-term psychotherapy may take place: evaluation, acquisition, and contextualization.

In the acquisition stage … new views about oneself are being “uploaded” in the form of new narratives. … using the same mechanisms that are at play during rearing and early nurturing.

The first stage, evaluation for new information, occurs when a patient familiarizes him/herself with the therapeutic setting and the analyst. This requires numerous adjustments and an amount of adaptational stress with its catecholamine secretion and formation of new implicit memories. In this stage, new information, perceived through the five senses, is also confronted with the primary affective states (instincts), which originate in the brain stem—seeking, play, panic, grief, fear, lust, and so on41—and with elements of implicit and explicit autobiography.

In the acquisition stage or self-reference stage, new views about oneself are being “uploaded” in the form of new narratives.1 Long-term memory and reconsolidation are necessary to be activated, as is the reference to one’s older narratives. The alternation between reflection and verbal exchange during psychotherapy creates an alternation of activation of the language brain bilaterally, like a “beltway” of communication and awareness with the deactivation of the default mode of midline structures. Through repetition and alternation of activation of these, major regions (midline vs external frontal temporal occipital brain surface) may connect by new links. Repeated and alternative stimulations create new links through synaptic protein syntheses and long-term potentiation associated with learning. Some of the newly acquired information may become stored as implicit memories in a variety of subcortical areas, linked to the midline structures of the self. By doing so, an experience becomes a “first-person experience” of the self, hence self-reference processing. The uploading of a new narrative uses the same mechanisms that are at play during rearing and early nurturing. Caretakers do provide, through an interactive manner of uploading, an image of the world for the developing child.42 During development such uploading is both verbal and nonverbal. In humans, speech itself has a privileged learning curve.43 A large well of research data comes from attachment studies and rating of the coherence of a narrative. Coherent narratives in caretakers have been highly correlated with mature attachment in offspring.44 By contrast, poorly coherent narratives, as rated on the Adult Attachment Interview, was highly correlated with immature type of attachment and personality pathology in offspring.45 Hence, healing changes in psychotherapy use preformed long-practiced, developmental pathways, explaining their profound impact on personality.

A stage of contextualization and reconsolidation of one’s autobiographic memory occurs through repetition and transference worked through in analysis. Reconsolidation as a memory mechanism has a particular role in reworking a person’s identity. Long-term fundamental personality changes may involve epigenetics, but the relationship must be further demonstrated by future research.

Conclusions

Transprocessing is a proposed mechanism by which changes during psychotherapy are internalized and assimilated. The implications of such a multistage mechanism are consistent with long-term clinical experience:

All psychotherapies have a common denominator: the restructuring of memories of old dysfunctional patterns of response to the routine social environment.

To produce pervasive changes, psychotherapies must include repeated reexposure to newly formed multimodal memories, hence the need for long-term therapies.

The emergence of new research that validates a neural model of psychotherapy may also call for public provision to further the availability of psychotherapy as a large-scale preventive and curative intervention. This may lead to further humanization of mental health treatment and to a shift toward a more integrative treatment approach in psychiatry.

Acknowledgments

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications and Leslie E Parker, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Panksepp J, Northoff G. The trans-species core SELF: the emergence of active cultural and neuro-ecological agents through self-related processing within subcortical-cortical midline networks. Conscious Cogn. 2009 Mar;18(1):193–215. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.03.002. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.con-cog.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damasio A. The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness. New York, NY: Mariner Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strehler BL. Where is the self? A neuroanatomical theory of consciousness. Synapse. 1991 Jan;7(1):44–91. doi: 10.1002/syn.890070105. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/syn.890070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parvizi J, Damasio A. Consciousness and the brain stem. Cognition. 2001 Apr;(1–2):79. 135–60. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00127-x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(00)00127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig AD. Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003 Aug;13(4):500–5. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00090-4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002 Aug;3(8):655–66. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panksepp J. At the interface of the affective, behavioral, and cognitive neurosciences: decoding the emotional feelings of the brain. Brain Cogn. 2003 Jun;52(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00003-4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panksepp J. On the embodied neural nature of core emotional affects. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 2005;12(8–10):158–84. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denton D. The primordial emotions: The dawning of consciousness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panksepp J. Affective consciousness: Core emotional feelings in animals and humans. Conscious Cogn. 2005 Mar;14(1):30–80. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2004.10.004. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alheid GF, Heimer L. New perspectives in basal forebrain organization of special relevance for neuropsychiatric disorders: the striatopallidal, amygdaloid, and corticopetal components of substantia innominata. Neuroscience. 1988 Oct;27(1):1–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90217-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0306-4522(88)90217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heimer L. A new anatomical framework for neuropsychiatric disorders and drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Oct;160(10):1726–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1726. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1726 Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry 2003 Dec;160(12):2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heimer L, Harlan RE, Alheid GF, Garcia MM, de Olmos J. Substantia innominata: a notion which impedes clinical-anatomical correlations in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuroscience. 1997 Feb;76(4):957–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00405-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4522(96)00405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pennebaker JW. Putting stress into words: health, linguistic and therapeutic implications. Behav Res Ther. 1993 Jul;31(6):536–48. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90105-4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(93)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandour J, Dzemidzic M, Wong D, et al. Temporal integration of speech prosody is shaped by language experience: an fMRI study. Brain Lang. 2003 Mar;84(3):318–36. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00505-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-934X(02)00505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandour J, Wong D, Lowe M, et al. A cross-linguistic FMRI study of spectral and temporal cues underlying phonological processing. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002 Oct 1;14(7):1076–87. doi: 10.1162/089892902320474526. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/089892902320474526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandour J, Wong D, Hsieh L, Weinzapfel B, Van Lancker D, Hutchins GD. A crosslinguistic PET study of tone perception. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000 Jan;12(1):207–22. doi: 10.1162/089892900561841. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/089892900561841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandour J, Wong D, Hutchins G. Pitch processing in the human brain is influenced by language experience. Neuroreport. 1998 Jun 22;9(9):2115–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806220-00038. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001756-199806220-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Indefrey P, Levelt WJ. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition. 2004 May-Jun;92(1–2):101–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2002.06.001. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2002.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein D, Zatorre RJ, Milner B, Zhao V. A cross-linguistic PET study of tone perception in Mandarin Chinese and English speakers. Neuroimage. 2001 Apr;13(4):646–53. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0738. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2000.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong RO, Ghosh A. Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic growth and patterning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002 Oct;3(10):803–12. doi: 10.1038/nrn941. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrn941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong PC, Perrachione TK, Parrish TB. Neural characteristics of successful and less successful speech and word learning in adults. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007 Oct;28(10):995–1006. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20330. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong PC, Parsons LM, Martinez M, Diehl RL. The role of the insular cortex in pitch pattern perception: the effect of linguistic contexts. J Neurosci. 2004 Oct 13;24(41):9153–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2225-04.2004. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEURO-SCI.2225-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Y, Gandour J, Talavage T, et al. Activation of the left planum temporale in pitch processing is shaped by language experience. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006 Feb;27(2):173–83. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20176. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zatorre RJ, Evans AC, Meyer E, Gjedde A. Lateralization of phonetic and pitch discrimination in speech processing. Science. 1992 May 8;256(5058):846–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1589767. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1589767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zatorre RJ, Evans AC, Meyer E. Neural mechanisms underlying melodic perception and memory for pitch. J Neurosci. 1994 Apr;14(4):1908–19. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01908.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catani M, Jones DK, Donato R, Ffytche DH. Occipito-temporal connections in the human brain. Brain. 2003 Sep;126(Pt 9):2093–107. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg203. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilgard MP, Merzenich MM. Cortical map reorganization enabled by nucleus basalis activity. Science. 1998 Mar 13;279(5357):1714–8. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1714. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5357.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauterborn JC, Rex CS, Kramár E, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2007 Oct 3;27(40):10685–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2624-07.2007. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2624-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynch G, Kramar EA, Rex CS, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor restores synaptic plasticity in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007 Apr 18;27(16):4424–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5113-06.2007. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5113-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rex CS, Lin CY, Kramár EA, Chen LY, Gall CM, Lynch G. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes long-term potentiation-related cytoskeletal changes in adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2007 Mar 14;27(11):3017–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4037-06.2007. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4037-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alberini CM. Mechanisms of memory stabilization: are consolidation and reconsolidation similar or distinct processes? Trends Neurosci. 2005 Jan;28(1):51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.001. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duvarci S, Nader K. Characterization of fear memory reconsolidation. J Neurosci. 2004 Oct 20;24(42):9269–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2971-04.2004. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2971-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) Arlington, VA: Amer Psychiatric Pub; 2000. Jun, pp. 298–323. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnosis criteria for research. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Letonoff EJ, Williams TR, Sidhu KS. Hysterical paralysis: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 Oct 15;27(20):E441–5. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000029268.16070.D8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF. Treatment of conversion disorder in the 21st century: have we moved beyond the couch? Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011 Jun;13(3):255–66. doi: 10.1007/s11940-011-0124-y. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11940-011-0124-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merskey H. Conversion disorders. In: Karasu TB, editor. American Psychiatric Association Task Force on treatments of psychiatric disorders. Vol. 3. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1989. pp. 2152–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stonnington CM, Barry JJ, Fisher RS. Conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Sep;163(9):1510–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1510. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moene FC, Hoogduin KA. The creative use of unexpected responses in the hypnotherapy of patients with conversion disorders. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 1999 Jul;47(3):209–26. doi: 10.1080/00207149908410033. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207149908410033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panksepp J. The periconscious substrate of consciousness: affective states and the evolutionary origins of the self. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 1998;5(5–6):566–82. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegel DJ. Mindsight: the new science of personal transformation. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chomsky N. Knowledge of language. In: Gunderson K, editor. Language, mind, and knowledge (Minnesota studies in the philosophy of science) Minneapolis, MN: University of Minneapolis; 1976. Jun, pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hesse E, Main M, Abrahams KY, Rifkin A. Unresolved states regarding loss or abuse can have “second-generation” effects. In: Solomon MF, Siegel DJ, editors. Healing trauma: attachment, mind, body, brain. New York, NY: WW Norton & Co; 2003. pp. 57–106. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyons-Ruth K, Dutra L, Schuder MR, Bianchi I. From infant attachment disorganization to adult dissociation: relational adaptations or traumatic experiences? Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006 Mar;29(1):63–86. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.011. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]