Abstract

Summary

Kinsenoside is able to improve bone turnover rate in ovariectomized (OVX) mice. In vitro analysis shows that kinsenoside antagonizes osteoclast development and bone resorption.

Introduction

Kinsenoside, the main active compound of the traditional Taiwanese herb Anoectochilus formosanus, has an antiinflammatory effect. This study investigates whether kinsenoside inhibits osteoporosis and osteoclastogenesis.

Methods

OVX mice were used to examine the antiosteoporotic activity of kinsenoside. The trabecular bone microarchitecture was assessed by microcomputed tomography. In vitro experiments were performed to determine the mechanisms of the antiosteoporotic effects of kinsenoside.

Results

Microcomputed tomography scanning showed that kinsenoside suppresses bone loss in OVX mice. Kinsenoside decreases plasma CTx concentration. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis also showed that kinsenoside reduces the femoral mRNA expression of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9). Kinsenoside inhibits osteoclast formation in bone marrow cells (BMs) and RAW 264.7 cells. Western blot was used to analyze osteoclast-associated signaling pathways in RAW 264.7 cells. Results show that kinsenoside does not inhibit IKK phosphorylation but suppresses the phosphorylation of IκBα and p65. Kinsenoside significantly inhibits the RANKL induction of IKK activity. Kinsenoside inhibits the RANKL-triggered nuclear translocations of NF-κB and nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 (NFATc1). RT-PCR was used to analyze osteoclast precursor fusion and resorption-associated gene expression in BMs. Kinsenoside inhibits the expression of cathepsin K (CAK), dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein, MMP-9, and TRAP.

Conclusions

Kinsenoside inhibits osteoclastogenesis from macrophages by attenuating RANKL-induced NF-κB and NFATc1 activities, which in turn, prevents bone loss from OVX mice.

Keyword: Kinsenoside, Osteoclastogenesis, Osteoporosis

Introduction

Bone remodeling depends on the balance between bone resorption and bone formation [1]. Postmenopausal osteoporosis reflects an imbalance in bone remodeling in which osteoclastic bone resorption exceeds osteoblastic bone formation [2]. The ovariectomized (OVX) model has been used as an animal model for various clinical syndromes derived from osteoporosis [3]. The serum concentration of C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (CTx) and the serum activity of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) are markers of bone resorption and bone formation, respectively [4]. Previous research has shown that CTx and ALP are significantly greater in an OVX group than in a sham-operated group [4].

Osteoclasts are bone-resorbing cells derived from hematopoietic precursors in the presence of the macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and the receptor activator of the nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) [5]. The binding of RANKL to its receptor RANK leads to the recruitment of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) to the cytoplasmic domain of RANK [6, 7]. The downstream targets of TRAF6 are predominantly mediated by a trimeric complex containing the NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO), an inhibitor of NF-κB kinase (IKK) α and IKKβ. IKK regulates the degradation of the inhibitor of NF-κB, IκBα, by promoting its phosphorylation and further degradation via the proteasome–ubiquitin pathway. Liberated NF-κB subsequently translocates into the nucleus, where it binds to DNA and promotes the transcription of various genes [8]. NF-κB is important for the initial induction of the nuclear factor of activated T cell c1 (NFATc1) expression. NFATc1 binds to its own promoter, thus switching on a robust induction of NFATc1 [8]. NFATc1 is likely a key regulator of RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation, fusion, and activation [9, 10].

Alendronate is a synthetic agent that is currently the most widely used drug for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Alendronate is a bone resorption inhibitor that maintains bone mass by inhibiting the function of osteoclasts [11]. Some people taking alendronate have experienced severe effects, such as osteonecrosis and insufficiency fractures [12, 13]. Growing evidence shows that the benefits of natural products, which are thought to be healthier and safer for the treatment of osteoporosis, can overcome the side effects of this synthetic drug.

Kinsenoside [3-(R)-3-β-d-glucopyranosyloxybutanolide] is a significant and active compound of the Anoectochilus formosanus (Orchidaceae), an important ethnomedicinal plant in Taiwan [14]. This compound has hepatoprotective, hypoglycemic, and antiinflammatory effects [15–17]. Kinsenoside inhibits NF-κB activation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in mouse peritoneal lavage macrophages (MPLMs) [17]. Several reports have shown that crude extracts of A. formosanus can ameliorate the osteoporosis induced by ovariectomy in rats [18, 19]. However, the antiosteoporotic activity of kinsenoside remains unclear.

This study investigates the effects of kinsenoside on osteopenia in OVX mice, using alendronate as a positive control drug. In vivo study indicates that the antiosteoporotic activity of kinsenoside might be related to its inhibitory effect on osteoclastogenesis. This study also investigates the effects of kinsenoside on RANKL-induced NF-κB activation and on osteoclastogenesis in osteoclast precursor cells.

Materials and methods

Preparation of kinsenoside

Kinsenoside was prepared by Professor Wu. The identity and purity of kinsenoside (>85 %) were analyzed by HPLC according to a previous report [15]. For the in vivo study, kinsenoside was dissolved in distilled water and concentrations of 10 and 30 mg/ml were prepared.

Animals

Female Wistar rats and imprinting control region (ICR) mice were purchased from BioLASCO Co., Ltd. (Taipei, Taiwan). The experimental animals received humane care, and the study protocols complied well with the institutional guidelines of the China Medical University for the use of laboratory animals. The animals were housed in an air-conditioned room (21–24 °C) under 12 h of light (7:00–19:00) and were allowed free access to food pellets and water throughout the study.

Animal experiments

Female mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, i.p.) for the bilateral removal of the ovaries. The mice in the sham-operated group were anesthetized, laparotomized, and sutured without removal of the ovaries. After 3 days of recovery from surgery, the OVX mice were randomly divided into four groups and orally treated with vehicle (H2O), kinsenoside (100 and 300 mg/kg daily), or alendronate (2.5 mg/kg every other day; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 4 weeks. The sham-operated group was orally treated with H2O only.

Plasma ALP levels were measured using clinical kits (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and a spectrophotometric system (Cobas Mira; Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Plasma CTx levels were determined using a mouse-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's protocols (Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics, Herlev Hovedgade, Denmark).

Microtomography analysis was performed as reported previously [20]. The trabecular bone microarchitecture of the distal right femoral metaphysis was measured using a microtomography scanner (SkyScan 1076, Kontizh, Belgium), with an isotropic resolution of 18 μm in all three spatial dimensions. Bone volume and tissue volume were measured directly from the original three-dimensional images, and trabecular bone volume (bone volume/tissue volume, percent) was calculated by dividing the bone volume by the total volume of interest. Other parameters of trabecular structure were studied, including thickness, separation, and the number of trabeculae, as calculated directly from three-dimensional images.

The left femur was removed, fixed with 4 % neutral-buffered paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) for 48 h, and decalcified in 10 % ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid solution (pH 7.4) at 4 °C for 4 weeks. After decalcification, each bone sample was cut along the coronal plane, embedded in paraffin, and cut longitudinally into sections for histological staining. For measurement of the osteoclast number, sections were stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) with TRAP kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as previously described [21].

To explore the mechanisms associated with kinsenoside on OVX-induced osteoporosis in mice, total RNA of the right tibiae was extracted for analysis of RT-PCR. The expression levels of ALP, matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), and TRAP were normalized to that of GAPDH mRNA in the same tissue. The PCR products were separated on a 2 % agarose gel and recorded on Polaroid film; the band was quantified with a densitometer. The mean ratio of each group was calculated as the average for eight animals. The fragments shown in Fig. 2e reflect the pooled data for eight samples.

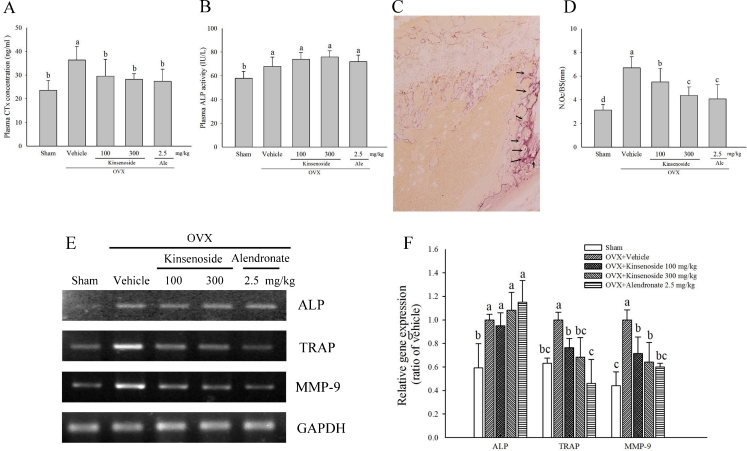

Fig. 2.

Biochemical, histological, and RT-PCR analyses on the metaphysis of the distal femur or tibiae in OVX mice. a Effects of kinsenoside on plasma ALP levels in OVX mice. b Effects of kinsenoside on plasma CTx levels in OVX mice. c Photomicrograph of femur section of OVX + H2O group. d Histogram representing the osteoclast number/mm bone surface (N. Oc/BS). e Fragments were amplified by RT-PCR. f The expression levels of ALP, TRAP, and MMP-9 mRNA were measured and quantified densitometrically. Values were normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression. All values are means ± SD (n = 8). Values not sharing a common superscript differ significantly. c 100×

Osteoclast differentiation of bone marrow cells

Bone marrow cells (BMs) were prepared by removing bone marrow from the femora and tibiae of Wistar rats weighing 220–250 g and then flushing the bone marrow cavity with α-MEM (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 20 mM HEPES, 10 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, penicillin (100 U ml−1), and streptomycin (100 μg ml−1). The nonadherent cells (hematopoietic cells) were collected after 24 h and used as osteoclast precursors. Cells were seeded in 1 × 106 cells/well in 24-well plates in the presence of RANKL (50 ng ml−1; PeproTech EC, London, UK) and M-CSF (20 ng ml−1; PeproTech EC). Cells were treated with kinsenoside based on findings that MPLMs do not undergo any change in viability after exposure to LPS+ kinsenoside. In addition, kinsenoside (IC50, 50 μM) inhibits the LPS-induced production of IL-1β. Various concentrations of kinsenoside (10, 25, and 50 μM) were added to these cultures for 9 days. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium every 3 days. Osteoclast formation was measured using the TRAP staining kit on day 9 [21]. Briefly, adherent cells were fixed with 10 % formaldehyde in PBS for 3 min and then stained with naphthol AS-Mx phosphate and tartrate solution for 1 h at 37 °C. TRAP-positive cells with more than three nuclei were scored as osteoclasts [22]. The viability of the BMs was detected by MTS assay (CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA).

Osteoclast differentiation of RAW 264.7 cells

RAW 264.7 cells, which are derived from murine macrophages and obtained from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan), were cultured in dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) (Hyclone Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10 % FBS, 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. For differentiation of osteoclasts, RAW 264.7 cells (1 × 103, in a 24-well plate) were cultured in the presence of the RANKL (50 ng/ml) for 5 days. The culture medium was replaced every 3 days. Various concentrations of kinsenoside (10, 25, and 50 μM) were added to these cultures. Osteoclast formation was measured using a TRAP staining kit. The viability of RAW 264.7 cells was also detected by the MTS assay.

Resorption pit assay

RAW264.7 cells were plated on BD BioCoat™ Osteologic™ at a density of 2,000 cells/well in a 96-well tissue culture plate, and incubated with different concentrations of kinsenoside (10, 25, and 50 μM) in the presence of RANKL (50 ng/ml) for 7 days. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing these stimuli every 3 days. After the culture, the slices were rinsed with PBS and left overnight in 1 M ammonium hydroxide to remove attached cells. Resorption pits on BD BioCoat™ Osteologic™ were counted using the Image Pro-plus program (v. 4.0).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

To determine NF-κB activation, the sequencing of the NF-κB-binding oligonucleotide used a cy5.5-5′-AGCTTGGGGACTTTCCGA-3′ DNA probe (Bio-Protech, Taipei, Taiwan) as fluorescence. Nuclear protein extracts from RAW 264.7 cells were prepared following the method of Chen et al. [23]. The DNA binding reaction with nuclear protein was performed at room temperature in a volume of 20 μl, which contained the binding buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)), 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), 50 nM cy5.5-labeled probe, 0.5 % Tween 20, and 15 μg of nuclear extracts. After incubation for 30 min, the samples were electrophoresized on native 5 % acrylamide gels prepared in a 0.5× TBE buffer (AMRESCO, Solon, OH, USA). Supershift assays using anti-p65 and anti-p50 antibody were also conducted to confirm the specificity of NF-κB DNA-binding activity. “Cold” represents a nuclear extract preincubated with an excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide. The gel was subsequently imaged with a LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) in 700-nm channels with a 169 μm resolution. The density of fluorescence in each band was measured in triplicate using LI-COR imaging software.

Immunofluorescent staining

Effects of kinsenoside on the nuclear translocation of p65 were examined by immunofluorescence, as described previously [24]. Briefly, 5 × 104 RAW 264.7 cells were seeded onto a 24-well plate preseeded with coverslips. After overnight incubation to allow for cell attachment, the cells were preincubated with kinsenoside (10, 25, and 50 μM) for 2 h before stimulation for 1 h with RANKL (50 ng/ml). After incubation, cells were washed twice with 1× PBS, fixed for 15 min at room temperature with 4 % paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS (pH 7.4), and then washed extensively with 1× PBS. Cells were then permeabilized in 1× PBS containing 0.1 % Triton X-100. After blocking with 0.1 % BSA-PBS, cells were incubated at 4 °C overnight with anti-p65 antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) diluted 1:200 in PBS. Cells were then labeled for 1 h at room temperature with an Alexa Fluor 488 phallotoxin (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR, USA) diluted 1:500 in PBS. Cells were then washed in PBS as before, counterstained for 3 min at room temperature with 4'-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., CA, USA), and mounted for confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP2, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Luciferase assay

To examine NF-κB activation, RAW 264.7 cells (5 × 104 in 1 ml of fresh medium) were seeded in a 24-well plate before transfection. The NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmids and pRL-TK used in this study were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). The DNA/jetPEI®-Macrophage mixture was then added to the cells. The cells were incubated in a humid atmosphere of 5 % CO2 at 37 °C for 6 h. After 6 h, the transfected cells were treated with kinsenoside for 120 min and then stimulated with RANKL (50 ng/ml) for 24 h. The cell lysates were then used for the luciferase assay. Luciferase activity was measured using a Promega Luciferase Assay System (Promega). The activity was measured using a Fluoroskan® Ascent FL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA). The cells were cotransfected with pRL-TK as an internal control to normalize the reporter gene activity and ensure the expression of luciferase in all subsequent experiments.

Western blot analysis

RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with or without RANKL in the presence or absence of kinsenoside. The extraction of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins was performed as described previously [24]. The primary antibodies were obtained from the following sources: p65, phosphorylated p65 (p-p65), IκBα, phosphorylated IκBα (p-IκBα), IKKα, IKKβ, and phosphorylated ΙΚΚα/β (p−ΙΚΚα/β) from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA), and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), α-tubulin, p50, and NFATc1 from Santa Cruz (CA, USA). The whole-protein extracts prepared following the method described by Lee et al. were used for the Western blot analysis of NFATc1 expression [25]. Western blot analysis was performed as described previously [17].

IKK activity assay

IKK activity was measured by an IKKα KinEASE™ FP Fluorescein Green Assay Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. A fluorescence polarization assay was performed using a Synergy 2 fluorescence plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., USA) with excitation set at 485 nm and emission at 530 nm.

RT-PCR analysis

The BMs were cultured for 3 days in the presence of M-CSF (20 ng/ml). Adherent cells were used as osteoclast precursors. To generate osteoclasts, osteoclast precursors were cultured with M-CSF (20 ng/ml) and RANKL (50 ng/ml) for 3 days in the presence of kinsenoside. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR primer sequences for mouse ALP, cathepsin K (CAK), dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP), MMP-9, RANK, TRAF6, and TRAP were as follows: primers for ALP were 5′-GTATGCCTCCTGCATTGGGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGTTCCTGCTGGAAGTTGCC-3′ (antisense); primers for CAK were 5′-CTGCCCATAACCTGGAGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCCCTGGTTCTTGACTGG-3′ (antisense); primers for DC-STAMP were 5′-ACCCGTTGCCCTGCTCTCTT-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACGGAGGCCACACGACAGAA-3′ (antisense); primers for GAPDH were 5′-CTTCATTGACCTCAACTACATGGTCTA-3′ (sense) and 5′-GATGACAAGCTTCCCATTCTCAG-3′ (antisense); primers for MMP-9 were 5′-GGTCTAGGCCCAGAGGTA-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGTCGTAGGTCACGTAGC-3′ (antisense); primers for RANK were 5′-GTGACTCTCCAGGTCACTCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGCAGACACACACTGTCG-3′ (antisense); primers for TRAF6 were 5′-GTTCTCAGGGAGCCCTAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAGGCACAGCTAAGGGAC-3′ (antisense); primers for TRAP were 5′-GAACCGTGCAGACGATGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGAAGTTCCAGCGCTTGG-3′ (antisense). The expected sizes of PCR products were 232 bp for ALP, 230 bp for CAK, 109 bp for DC-STAMP, 99 bp for GAPDH, 310 bp for MMP-9, 134 bp for RANK, 364 bp for TRAF6, and 231 bp for TRAP. All primer sets were designed using NCBI/Primer-BLAST.

Statistical analysis

This study expresses results as the mean ± SD. All experimental data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following the Duncan's test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

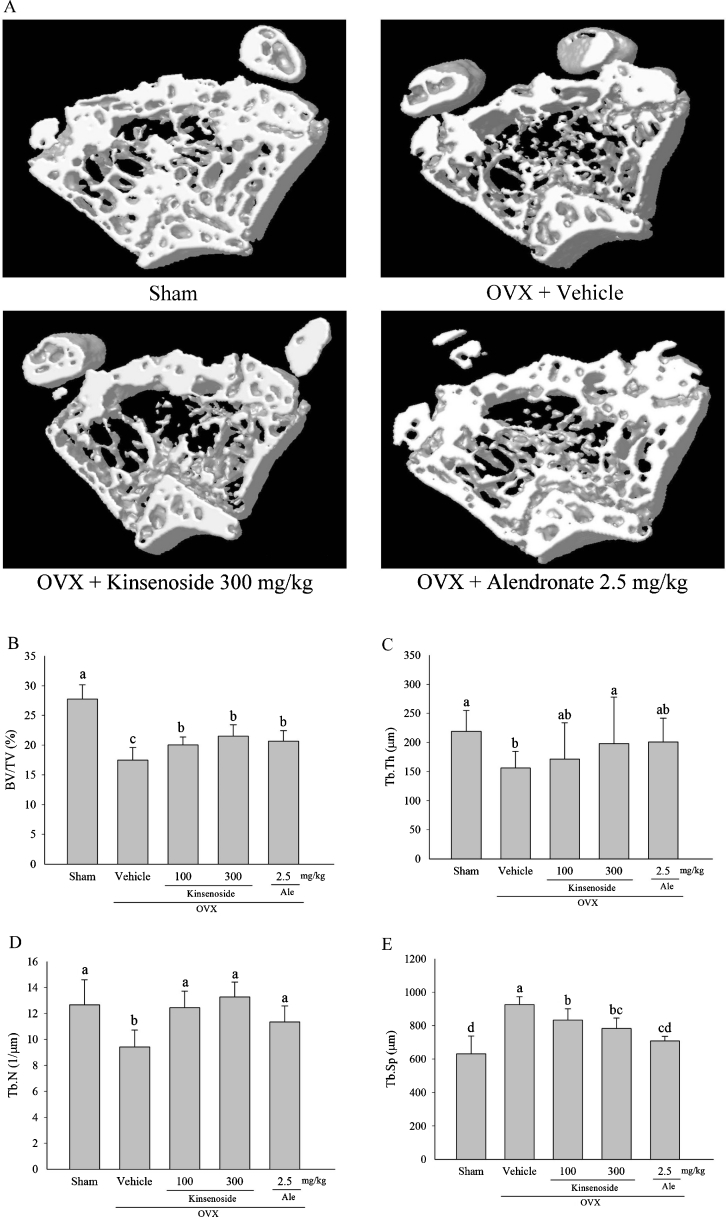

MicroCT analysis in OVX mice

Figure 1a shows 3D renderings of the trabecular bone compartment as imaged by micro-computed tomography (microCT). Microtomography scanning showed that trabecular bone volume (38 %; p < 0.05), trabecular thickness (29 %; p < 0.05), and the number of trabeculae (25 %; p < 0.05) in the distal femoral metaphysis decreased significantly in OVX mice (Fig. 1b–d). In addition, trabecular separation (42 %; p < 0.05) in the distal femoral metaphysis increased significantly in OVX mice (Fig. 1e). Treating OVX mice with kinsenoside led to a 14 % (100 mg/kg; p < 0.05) and 23 % increase (300 mg/kg; p < 0.05) in trabecular bone volume, a 28 % increase (300 mg/kg; p < 0.05) in trabecular thickness, a 13 % (100 mg/kg; p < 0.05) and 40 % increase (300 mg/kg; p < 0.05) in the number of trabeculae, and an 8 % (100 mg/kg; p < 0.05) and 15 % (300 mg/kg; p < 0.05) decrease in trabecular separation. Treating OVX mice with alendronate produced a 17 % (p < 0.05) increase in trabecular bone volume, a 20 % (p < 0.05) increase in the number of trabeculae, and a 24 % (p < 0.05) decrease in trabecular separation.

Fig. 1.

Microtomography analysis of metaphysic of the distal femurs in OVX mice of different groups. a Representative sample from each group: 3D architecture of trabecular bone within the distal femoral metaphyseal region. Effects of kinsenoside and alendronate on the trabecular bone volume (b), thickness of the trabeculae (c), number of trabeculae (d), and separation of trabeculae (e) of the distal femoral metaphysic in OVX rats by microtomography analysis. Values are means ± SD (n = 8). Values not sharing a common superscript differ significantly. Ale alendronate, BV/TV bone volume/tissue volume, Tb.Th thickness of the trabeculae, Tb.N number of trabeculae, Tb.Sp separation of trabeculae

Biochemical analysis in OVX mice

Four weeks after the operation, the OVX mice showed significant increases in plasma CTx concentrations (p < 0.05) and ALP activities (p < 0.05), compared with the sham-operated mice (Fig. 2a). Four weeks after kinsenoside administration, mice in the OVX + vehicle and OVX + kinsenoside groups showed no differences in the plasma level of ALP. The OVX mice receiving kinsenoside (100 and 300 mg/kg; p < 0.05) and alendronate (2.5 mg/kg every other day; p < 0.05) for 4 weeks had significantly lowered plasma CTx concentration.

Bone histology analysis in OVX mice

Figure 2c and d show that the number of osteoclasts in the region of the primary spongiosa significantly increased in the OVX mice (p < 0.05). Kinsenoside (100 and 300 mg/kg) and alendronate treatments decreased the number of osteoclasts in OVX mice (p < 0.05).

RT-PCR analysis of tibial mRNA expression in OVX mice

The fragments shown in Fig. 2e reflect the pooled data for eight samples. The RT-PCR analysis of the tibial sample in Fig. 2f shows that the expressions of ALP, TRAP, and MMP-9 were 168 % (p < 0.05), 157 % (p < 0.05), and 220 % (p < 0.05) higher in the OVX group than in the sham group. Treatment with kinsenoside led to 23 % (100 mg/kg) and 32 % (300 mg/kg; p < 0.05) decreases in TRAP expression and 27 % (100 mg/kg, p < 0.05) and 36 % (300 mg/kg, p < 0.05) decreases in MMP-9 expression. Treatment with alendronate led to a 54 % (p < 0.05) decrease in TRAP expression and a 41 % (p < 0.05) decrease in MMP-9 expression. Kinsenoside and alendronate did not affect ALP mRNA expression.

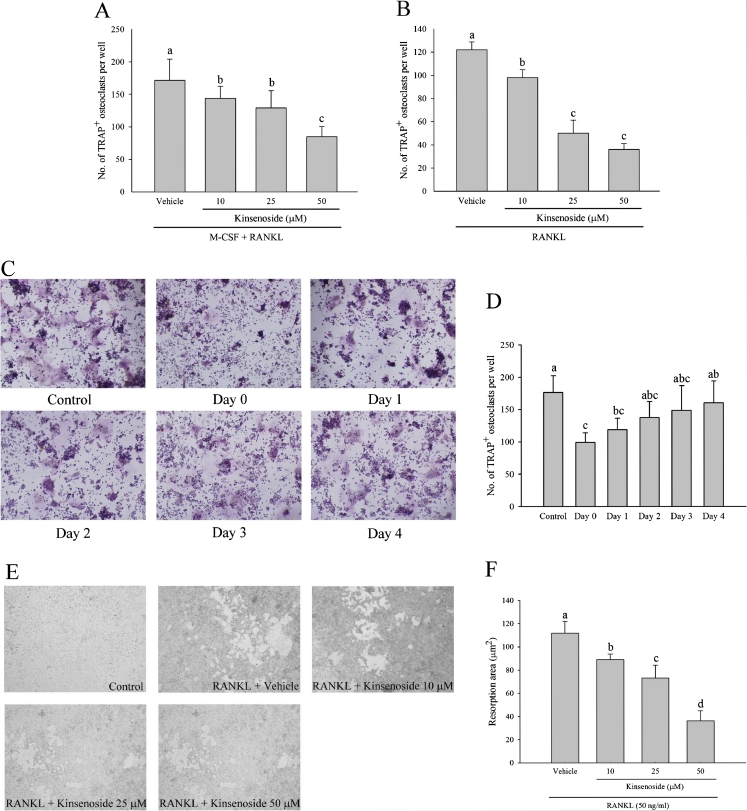

Kinsenoside inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis of BMs and RAW 264.7 cells

Treating BMs with kinsenoside (10–50 μM) for 3 days did not affect cell viability, which was assessed by the MTS assay (data not shown). Figure 3a shows that kinsenoside does-dependently inhibited the formation of large TRAP-positive multinucleated osteoclasts in BM cultures in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL. Kinsenoside inhibited osteoclast formation by 17 % (p < 0.05), 26 % (p < 0.05), and 50 % (p < 0.05) at 10, 25, and 50 μM, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Kinsenoside inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. a BMs were cultured with the indicated dose of kinsenoside in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL. After 9 days, cells were fixed and stained with TRAP. Multinucleated osteoclasts were counted. b RAW 246.7 cells were cultured with the indicated dose of kinsenoside in the presence of RANKL. After 5 days, cells were fixed and stained with TRAP. Multinucleated osteoclasts were counted. c Kinsenoside inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis at an early stage. The TRAP stains of osteoclasts were treated with kinsenoside (50 μm) at the same time or after indicated time periods. Cells were cultured for 5 days after RANKL treatment and stained for TRAP expression. Multinucleated osteoclasts were counted. The quantitative data are shown in d. e RAW 246.7 cells plated on BD BioCoat™ Osteologic™ and incubated with different concentrations of kinsenoside in the presence of RANKL (50 ng/ml) for 7 days. Cells were removed by washing with distilled water and resorbed areas were measured. The quantitative data are shown in f. All values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). Values not sharing a common superscript differ significantly. c ×100

Treating RAW 264.7 cells with kinsenoside (10–50 μM) for 3 days did not affect cell viability, which was assessed by the MTS assay (data not shown). Figure 3b shows that kinsenoside dose-dependently inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation in RAW 364.7 cells. Kinsenoside inhibited osteoclast formation by 20 % (p < 0.05), 60 % (p < 0.05), and 71 % (p < 0.05) at 10, 25, and 50 μM, respectively.

Kinsenoside inhibited early-stage osteoclastogenesis

Complete osteoclast differentiation of RAW 264.7 cells takes up to 5 days after RANKL stimulation. To identify which stage of osteoclastogenesis was affected by kinsenoside, RAW 264.7 cells were treated with 50 μM of kinsenoside on different days, from Day 0 to Day 4 after RANKL stimulation. Kinsenoside inhibited osteoclast formation by concurrent addition (Day 0) or by Day 1 after RANKL stimulation (Fig. 3c and d). When kinsenoside was added to the culture for the final 3 days (Days 2–4), it failed to suppress RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Kinsenoside inhibited osteoclast formation by 44 % (p < 0.05) and 32 % (p < 0.05) at Day 0 and Day 1, respectively.

Kinsenoside inhibited bone resorption

RAW264.7 cells were plated on bone slices and stimulated with RANKL in the presence or absence of kinsenoside. RANKL-stimulated cells formed a number of pits (Fig. 3e), indicating that the bone resorption activity of RANKL-treated cells transformed them into functionally active state resembling osteoclasts. Treatment with kinsenoside (10–50 μM) significantly reduced the number and area of resorption pits compared with RANKL treatment alone. Kinsenoside inhibited osteoclast resorption by 20 % (10 μM; p < 0.05), 34 % (25 μM; p < 0.05), and 67 % (50 μM; p < 0.05).

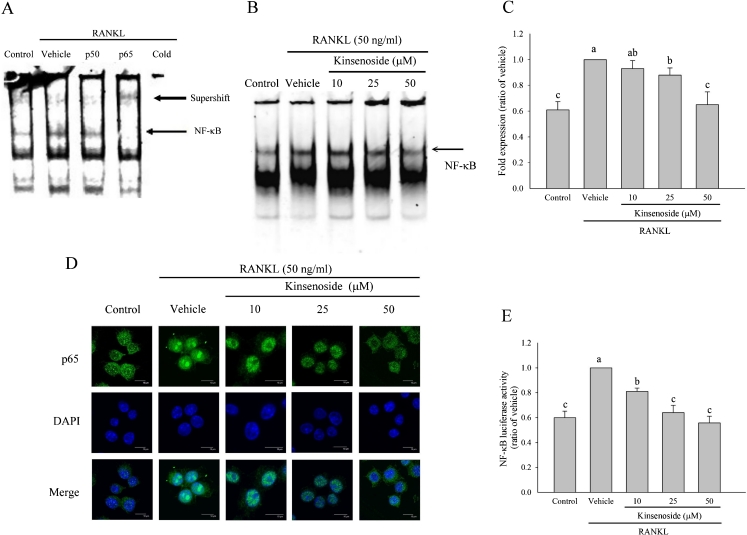

Kinsenoside inhibited RANKL-induced NF-κB activation by electrophoretic mobility shift assay

RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with kinsenoside for 2 h and then treated with RANKL for 1 h. The prepared nuclear extracts were then assayed for NF-κB activation by the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Figure 4a–c show that RANKL treatment caused a significant increase in the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB (p < 0.05). Treating RAW 264.7 cells with kinsenoside (25 and 50 μM) significantly suppressed the RANKL-induced DNA-binding activity of NF-κB by 13 % (p < 0.05) and 35 % (p < 0.05), respectively.

Fig. 4.

Kinsenoside inhibited RANKL-induced transcriptional activity of NK-κB in RAW 264.7 cells. a EMSA results showed a supershift of complex formed in the presence of anti-p50 and anti-p65 antibodies. The p65 subunits cause a specific binding of NF-κB to consensus DNA sequence. Cold the nuclear extract was preincubated with an excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide. b RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with or without the indicated concentrations of kinsenoside for 2 h and then treated with RANKL for 1 h and tested for nuclear NF-κB by EMSA. The quantitative data are shown in c. d RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with kinsenoside and then stimulated with RANKL for 1 h. The localization of p65 was visualized by immunofluorescence analysis. e RAW 264.7 cells were transiently transfected with an NF-κB promoter plasmid for 16 h. After transfection, the cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of kinsenoside for 2 h and then treated with RANKL for an additional 24 h. Cells were lysed, and the luciferase activity was determined by using a luciferase reporter assay system. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). Values not sharing a common superscript differ significantly

Kinsenoside inhibited RANKL-induced NF-κB activation by immunofluorescence staining

Figure 4d shows that, in the absence of RANKL, most p65 were located in the cytoplasm. However, nearly all p65 was located in the nucleus after RANKL stimulation. The nuclear translocation of p65 was blocked when incubation occurred with 25 and 50 μM kinsenoside combined with RANKL.

Kinsenoside inhibited RANKL-induced NF-κB activation by luciferase assay

The luciferase reporter gene assay in this study shows the effects of kinsenoside on NF-κB activity. RAW 264.7 cells were transiently transfected with an NF-κB-driven luciferase reporter construct. RANKL induced an increase in NF-κB promoter-driven luciferase gene expression compared to RAW 264.7 cells cultured in a medium without RANKL (Fig. 4e; p < 0.05). Treating RAW 264.7 cells with kinsenoside (10, 25, and 50 μM) strongly inhibited RANKL-induced NF-κB transcriptional activation by 20 % (p < 0.05), 37 % (p < 0.05), and 45 % (p < 0.05), respectively.

Effects of kinsenoside on nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 in RANKL-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells

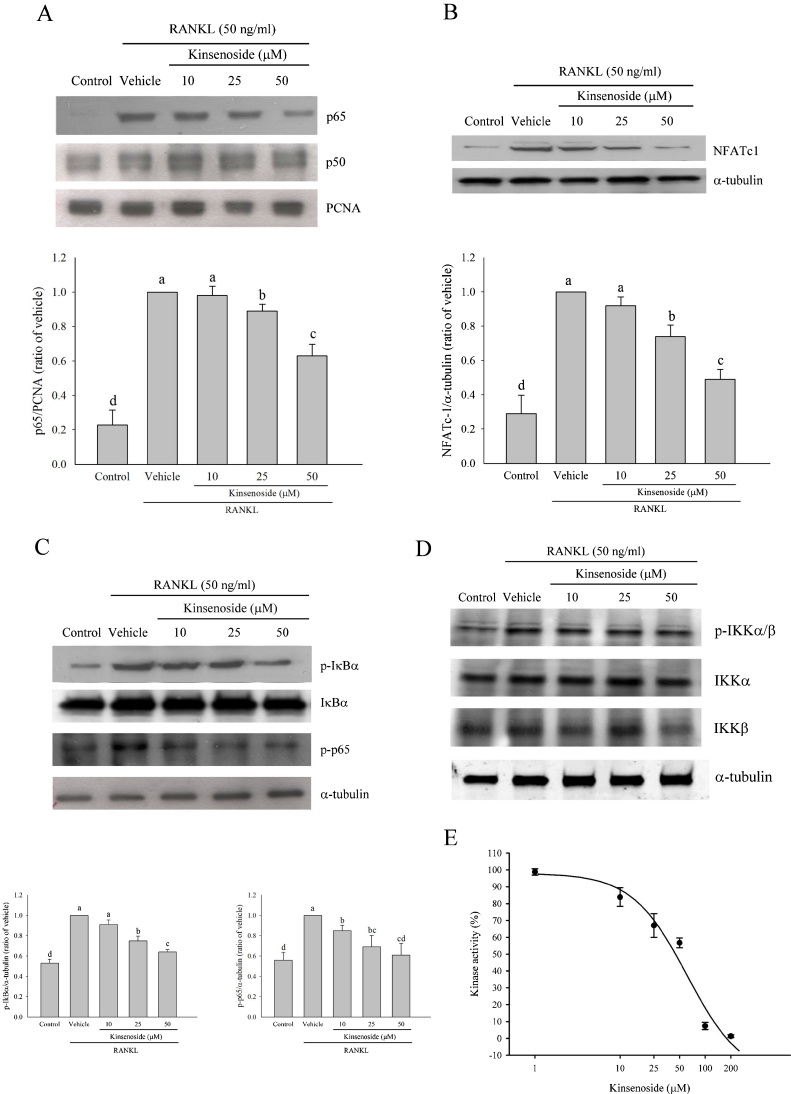

Treatment with RANKL for 60 min caused the translocation of p65, but not p50, into the nucleus by Western blot analysis (p < 0.05). The nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit in the RANKL group was 4.2 times greater than that in the control group (Fig. 5a). RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with kinsenoside for 120 min and then treated with RANKL. Kinsenoside led to a 12 % (25 μM; p < 0.05) and 38 % (50 μM; p < 0.05) decrease in p65 expression (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Western blot analysis and kinase activity assay of IKKα. a RAW 264.7 cells were preincubated for 2 h with indicated concentrations of kinsenoside and then activated for 1 h with RANKL. Nuclear fractions were obtained for the detection of p65 and p50 levels. b RAW 264.7 cells were preincubated for 2 h with indicated concentrations of kinsenoside and then activated for 24 h with RANKL. The whole proteins were obtained for the detection of NFATc1 levels. c Cytoplasmic fractions were obtained for the detection of p-IκBα, IκBα, and p-p65 levels. d Cytoplasmic fractions were obtained for the detection of IKKα, IKKβ, and p-IKKα/β levels. All values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). Values not sharing a common superscript differ significantly. e In vitro kinase assay of IKK was done as described in “Materials and methods”. The IC50 values were approximately 57.6 μM. Values were expressed as means ± SD (n = 3)

Kinsenoside inhibited NFATc1 expression

RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with RANKL in the presence or absence of kinsenoside for 2 h. Treatment with RANKL for 24 h raised the protein expression levels of NFATc1 by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5b; p < 0.05). The expression level of NFATc1 in the RANKL group was 3.5 times greater than that in control group. Pretreatment with kinsenoside led to a 40 % (25 μM; p < 0.05) and 60 % (50 μM; p < 0.05) decrease in NFATc1 expression (Fig. 5b).

Effects of kinsenoside on cytoplasmic phosphorylation levels of p-IκBα, p-p65, and p-IKKα/β in RANKL-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells

RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with RANKL in the presence or absence of kinsenoside for 2 h. Treatment with RANKL for 1 h increased the cytoplasmic phosphorylation levels of p-IκBα, p-p65, and p-IKKα/β, but not IκBα, IKKα, and IKKβ, by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5c and d). The phosphorylation levels of p-IκBα and p-p65 in the RANKL group were 182 % (p < 0.01) and 182 % (p < 0.05), respectively, both of which were greater than those in the control group. Kinsenoside treatment did not affect the level of IκBα. Kinsenoside treatment led to 27 % (25 μM; p < 0.05) and 39 % (50 μM; p < 0.05) decreases in p-IκBα level and 16 % (10 μM; p < 0.05), 32 % (25 μM; p < 0.05), and 39 % (50 μM; p < 0.05) decrease in p-p65 level (Fig. 5c).

The levels of p-IKKα/β in the RANKL group were 145 % (p < 0.05) greater than that in the control group. Kinsenoside treatment did not affect the levels of IKKα, IKKβ, and p-IKKα/β (Fig. 5d).

Kinsenoside inhibited IKK activity

To determine whether kinsenoside interacts with IKK directly, this study examines the effects of kinsenoside on IKK enzymatic activity. The culture treatment of RAW 264.7 cells with 50 ng/ml RANKL for 1 h effectively increased IKK activity. Kinsenoside treatment (10–200 μM) for 2 h inhibited IKK activity in a concentration-dependent manner. The IC50 value was approximately 57.6 μM (Fig. 5e).

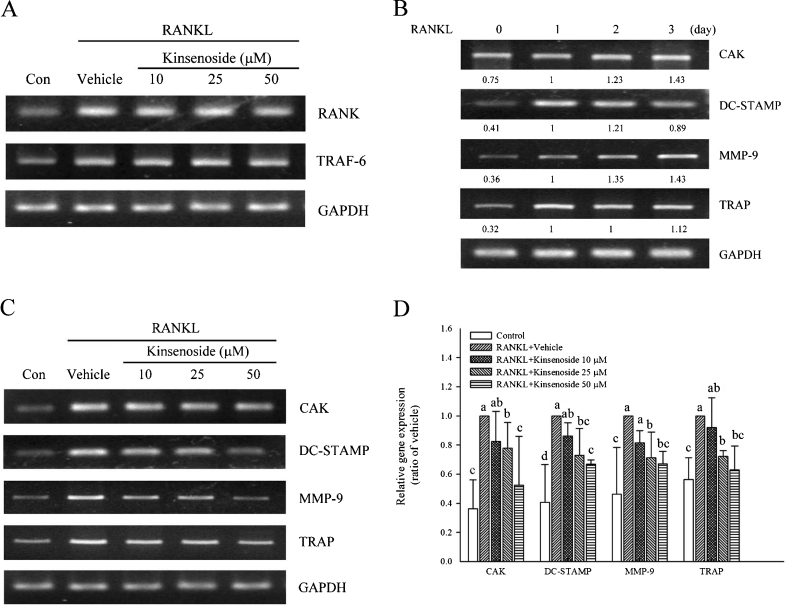

Kinsenoside did not affect the mRNA expression of RANK and TRAF6

The fragments shown in Fig. 6a reflect the pooled data for three samples. The BMs were incubated with M-CSF (20 ng/ml) for 3 days to induce the production of osteoclast precursor. Osteoclast precursors incubated with kinsenoside for 120 min were then treated with M-CSF (20 ng/ml) and RANKL (50 ng/ml) for 1 day in the presence or absence of kinsenoside. As Fig. 6a shows, RT-PCR amplified fragments of RANK and TRAF6. The RANK/GAPDH and TRAF6/GAPDH ratios in the RANKL group were 170 % (p < 0.05) and 220 % (p < 0.05), respectively, both of which are greater than those in the control group. Kinsenoside treatment (10–50 μM) did not affect the ratios of RANK/GAPDH and TRAF6/GAPDH (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Effects of kinsenoside on expression of RANKL-regulated genes. a BMs were preincubated for 2 h with indicated concentrations of kinsenoside and then activated for 24 h with RANKL. RANK and TRAF6 mRNAs were amplified by RT-PCR. b Total RNA from BMs was isolated on the indicated days after RANKL incubation, and mRNA expression of TRAP, DC-STAMP, CAK, and MMP-9 was analyzed by RT-PCR. c BMs were preincubated for 2 h with indicated concentrations of kinsenoside and then activated for 24 h with RANKL. TRAP, DC-STAMP, CAK, and MMP-9 mRNAs were amplified by RT-PCR. The quantitative data are shown in d. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). ## p < 0.01 as compared with the control group. Values not sharing a common superscript differ significantly

Kinsenoside inhibited the mRNA expression of CAK, DC-STAMP, MMP-9, and TRAP

The osteoclast fusion and resorption-related gene were activated lately. To confirm the RANKL-induced expression of these genes, mRNA was extracted 24, 48, and 72 h after RANKL challenge for RT-PCR analysis. Figure 6b shows that all TRAP/GAPDH, DC-STAMP/GAPDH, MMP-9/GAPDH, and CAK/GAPDH ratios in the 24–72 h after RANKL treatments were greater than those in the control group. Therefore, mRNA from BMs challenged with RANKL for 24 h was used to examine the effects of kinsenoside. Figure 6c and d show that kinsenoside treatment (10–50 μM) led to 22 % (25 μM; p < 0.05) and 48 % (50 μM; p < 0.05) decreases in CAK expression, 27 % (25 μM; p < 0.05) and 33 % (50 μM; p < 0.05) decreases in DC-STAMP expression, 28 % (25 μM; p < 0.05) and 33 % (50 μM; p < 0.05) decreases in MMP-9 expression, and 28 % (25 μM; p < 0.05) and 37 % (50 μM; p < 0.05) decreases in TRAP expression.

Discussion

In the present study, kinsenoside ameliorated OVX-induced osteopenia in mice, through the inhibition of osteoclatogenesis. The in vitro study also indicates that kinsenoside inhibits osteoclastogenesis from BMs and RAW 264.7 cells.

This study used a mouse model to evaluate the efficacy of kinsenoside in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Microtomographic scanning shows a decrease in trabecular bone volume, thickness, and the number of trabeculae, with an increase in the trabecular separation of the metaphysis of the femur in the OVX mice. Treatment with kinsenoside significantly reduced this bone loss in the OVX mice.

The plasma activity of ALP, an index of bone formation [4], was reported to be significantly greater in an OVX group than in a sham-operated group [4]. A similar change was observed in the present study. Kinsenoside treatment did not influence the activity of plasma ALP. CTx is a marker of bone resorption [4], and OVX increases the content of CTx in the plasma; however, this effect was decreased through treatment with kinsenoside. These results suggest that kinsenoside ameliorated bone loss induced by OVX by inhibiting bone resorption as opposed to enhancing bone formation. In the present study, kinsenoside ameliorated OVX-induced osteopenia in mice through the inhibition of osteoclatogenesis. The in vitro study also indicates that kinsenoside inhibits osteoclastogenesis from BMs and RAW 264.7 cells.

Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells of hematopoietic origin and are the primary bone-resorbing cells [5]. TRAP is a different form of the enzyme acid phosphatase, which is found mainly in bone. Osteoclasts release TRAP during bone resorption [21]. Histological sections stained with TRAP showed that the number of osteoclasts decreased in the region of the spongiosa in kinsenoside-treated OVX mice. TRAP activity is commonly used as a histochemical marker of identifying osteoclasts [26]. MMP-9 is required for osteoclastic migration and resorption [27]. Kinsenoside treatment inhibited the mRNA expression of femoral TRAP and MMP-9, but not ALP. These findings indicate that kinsenoside can suppress the differentiation and resorption of osteoclasts. These results agree with the findings obtained by Masuda et al., who showed that the ethanolic extract of A. formosanus inhibited bone loss caused by OVX by suppressing osteoclast formation [18].

Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells originating from the fusion of mononuclear progenitors in the monocyte/macrophage family [28]. Previous research has shown that two key molecules, M-CSF and RANKL, are essential and sufficient to promote osteoclastogenesis [8]. Thus, M-CSF and RANKL were added to induce osteoclastogenesis in the primary BM cell culture system. In the RAW 264.7 macrophage cell-cultured system, only RANKL was added to induce osteoclast differentiation. In this study, kinsenoside dose-dependently suppressed the formation of osteoclasts in BMs and a RAW 264.7 cell culture system. Results further show that RAW 264.7 cells were markedly blocked by the concurrent administration of RANKL and kinsenoside and weakly blocked by subsequent addition of kinsenoside. This suggests that inhibition occurred during the initial stage of osteoclastogenesis.

Previous research has shown that M-CSF enhances RANKL-induced osteoclast formation [29]. To exclude the interference of M-CSF, therefore, RANKL-induced RAW 264.7 cell differentiation into osteoclastlike cells was used to assess the effects of kinsenoside on the signal transduction pathway. In addition, a BM system was used to examine the effects of kinsenoside on osteoclast precursor fusion, osteoclast formation, and resorption.

Activation of the NF-κB pathway is a key factor in RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation [10]. The results of EMSA analysis show that kinsenoside inhibits the RANKL-induced DNA binding activity of p65. Immunofluorescence staining and Western blot analysis of nuclear protein also show that kinsenoside suppressed the nuclear translocation of p65 protein. Using transient transfection with κB-luciferase as an indicator of NF-κB activity, this study shows that kinsenoside inhibits the RANKL-increased NF-κB activity. These results clearly show that the antiosteoclastogenic effects of kinsenoside may occur through the inhibition of NF-κB signaling.

RANK lacks intrinsic enzymatic activity in its intracellular domain, and it transduces signaling by recruiting adaptor molecules such as the TRAF family of proteins [8]. Genetic experiments show that TRAF6 is required for osteoclast formation and osteoclast activation [30]. The binding of RANKL to its receptor RANK recruits TRAF6 and subsequently initiates a kinase cascade. RT-PCR analysis shows that kinsenoside did not reduce the RANKL-induced mRNA expression of RANK and TRAF-6, indicating that kinsenoside inhibits NF-κB activation through downstream kinase to TRAF6.

The classical NF-κB signaling pathway involves the activation of the IKK complex, which phosphorylates IκBα and targets them for ubiquitin-dependent degradation [8]. In the alternative IκB-independent pathway, direct phosphorylation of NF-κB subunit p65 by IKK also modulates NF-κB transcription activity [31]. In this study, kinsenoside inhibited RANKL-induced NF-κB activation in RAW 264.7 cells by inhibiting p-IκBα and p-p65. This indicates that kinsenoside inhibited NF-κB translocation through both IκBα-dependent and IκBα-independent pathways.

IKK is the major upstream kinase of IκBα in the NF-κB signaling pathway. In this study, kinsenoside did not inhibit IKK phosphorylation but suppressed the phosphorylation of IκBα and p65. Therefore, this study also investigates the effects of kinsenoside on IKK activity. Results show that kinsenoside significantly inhibits RANKL induction of IKK activity, suggesting that IKK is a critical target for kinsenoside in inhibiting RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis.

NFATc1 is likely a key regulator of RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation, fusion, and activation [10]. NF-κB is important for the initial induction of NFATc1. The binding of NF-κB to the NFATc1 promoter region induces NFATc1 gene expression, allowing NFATc1 to autoamplify its expression by binding to its own promoter. This, in turn, leads to the robust induction of NFATc1 during RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation [32]. In this study, kinsenoside significantly suppressed RANKL-induced NF-κB translocation and NFATc1 nuclear transport.

NFATc1 promotes the expression of osteoclast-specific genes such as TRAP, DC-STAMP, CAK, and MMP-9 [33–35]. In addition to histochemical marker for osteoclasts, TRAP also regulates bone resorption by mediating the degradation of endocytosed matrix products during transcytosis in activated osteoclasts [36]. DC-STAMP, a putative seven-transmembrane spanning protein, is essential for the cell–cell fusion of osteoclasts [37]. Proteinases are necessary for bone resorption. Delaisse et al. showed that CAK and MMP-9 are key proteinases in the bone resorption processes [38]. The RT-PCR analysis in this study shows that kinsenoside dose-dependently suppressed the mRNA expression of TRAP, DC-STAMP, CAK, and MMP-9. Thus, kinsenoside, which downregulates NF-κB and NFATc1 activities, caused substantial inhibition of osteoclast differentiation, fusion, and resorption mediated by RANKL.

This study shows that kinsenoside reduces osteoporosis induced by OVX in mice. Second, kinsenoside has the potential to inhibit the formation of osteoclasts by inhibiting IKK activity, which might influence the activation of NF-κB and NFAcT1. Third, kinsenoside may suppress the bone resorption activity of mature osteoclasts by regulating the expression of osteoclast fusion-related and resorption-related genes.

Many synthetic agents, such as bisphosphonates and raloxifene, have been developed to treat osteoporosis. However, these drugs are associated with side effects such as dyspepsia and breast cancer. Thus, scientists are pursuing the development of natural products. This study investigates the efficacy of kinsenoside in treating osteoporosis. Recently, we also found that A. formosanus contains prebiotic polysaccharides that could reduce the osteopenia induced by OVX in rats by increasing the concentration of cecal short chain fatty acids (SCFA) [39]. Butyric acid, an SCFA, can stimulate the formation of osteoblasts [40, 41]. Therefore, it is possible that the extract of A. formosanus may ameliorate bone loss caused by OVX by stimulating bone formation and inhibiting bone resorption [19]. This study proposes the possibility of using A. formosanus in the development of therapeutic drugs for osteoporosis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the China Medical University (CMU 99-S-15).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Matsuo K. Cross-talk among bone cells. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18:292–297. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32832b75f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teitelbaum SL. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jee WSS, Yao W. Overview: animal models of osteopenia and osteoporosis. J Musculoskel Neuron Interact. 2001;1:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon KH, Cho DC, Yu SH, Kim KT, Jeon Y, Sung JK. The change of bone metabolism in ovariectomized rats: analyses of microCT scan and biochemical markers of bone turnover. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;51:323–327. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.51.6.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wada T, Nakashima T, Hiroshi N, Penninger JM. RANKL-RANK signaling in osteoclastogenesis and bone disease. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galibert L, Tometsko ME, Anderson DM, Cosman D, Dougall WC. The involvement of multiple tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factors in the signaling mechanisms of receptor activator of NF-kappaB, a member of the TNFR superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34120–34127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darnay BG, Ni J, Moore PA, Aggarwal BB. Activation of NF-kappaB by RANK requires tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 6 and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. Identification of a novel TRAF6 interaction motif. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7724–7731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asagiri M, Takayanagi H. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2007;40:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takayanagi H, Kim S, Koga T, Nishina H, Isshiki M, Yoshida H. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev Cell. 2002;3:889–901. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Q, Wang X, Liu Y, He Y, Jia R. NFATc1: functions in osteoclasts. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:546–579. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eslami B, Zhou S, Van Eekeren I, Leboff MS, Glowacki J. Reduced osteoclastogenesis and RANKL expression in marrow from taking alendronate. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;88:272–280. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9473-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverman SL, Landesberg R. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and the role of bisphosphonates: a critical review. Am J Med. 2009;22:S33–S45. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai K, Yamamoto S, Anamizu Y, Horiuchi T. Plevic insufficiency fracture associated with severe suppression of bone turnover by alendronate therapy. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:333–336. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0771-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du XM, Irino N, Furusho N, Hayashi J, Shoyama Y. Pharmacologically active compounds in the Anoectochilus and Goodyera species. J Nat Med. 2008;62:132–148. doi: 10.1007/s11418-007-0169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu JB, Lin WL, Hsieh CC, Ho HY, Tsay HS, Lin WC. The hepatoprotective activity of kinsenoside from Anoectochilus formosanus. Phytother Res. 2007;21:58–61. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Cai J, Ruan H, Pi H, Wu J. Antihyperglycemic activity of kinsenoside, a high yielding constituent from Anoectochilus roxburghii in streptozotocin diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiao HB, Wu JB, Lin H, Lin WC. Kinsenoside isolated from Anoectochilus formosanus suppresses lipopolysaccharide-stimulated inflammatory reactions in macrophages and endotoxin shock in mice. Shock. 2011;35:184–190. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181f0e7a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuda K, Ikeuchi M, Koyama T, Yamaguchi K, Woo JT, Nishimura T. Suppressive effects of Anoectochilus formosanus extract on osteoclast formation in vitro and bone resorption in vivo. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26:123–129. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shih CC, Wu YW, Lin WC. Ameliorative effects of Anoectochilus fromosanus extract on osteopenia in ovariectomized rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;77:233–238. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouxsein M, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Muller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole AA, Walters LM. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase in bone and cartilage following decalcification and cold-embedding in plastic. J Histochem Cyrochem. 1987;35:203–206. doi: 10.1177/35.2.3540104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asagiri M, Takayanagi H. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2007;40:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CC, Wang JK, Lin SB. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting protein kinase C-alpha, -beta I, or -delta but not -eta inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthase expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages: involvement of a nuclear factor kappa B-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 1998;161:6206–6214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ang E, Liu Q, Qi M, Liu HG, Yang X, Chen H, Zheng MH, Xu J. Mangiferin attenuates osteoclastogenesis, bone resorption, and RANKL-induced activation of NF-κB and ERK. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:89–97. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Jin H, Shim HE, Kim HN, Ha H, Lee ZH. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits osteoclastogenesis by down-regulating c-Fos expression and suppressing the nuclear factor-kappaB signal. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:17–25. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.057877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh NC, Cahill M, Carninci P, Kawai J, Okazaki Y, Hayashizaki Y. Multiple tissue-specific promoters control expression of the murine tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase gene. Gene. 2003;307:111–123. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delaissé JM, Engsig MT, Everts V, del Carmen OM, Ferreras M, Lund L. Proteinases in bone resorption: obvious and less obvious roles. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;291:223–234. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(99)00230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Akatsu T, Tanaka H, Sasaki T, Nishihara T. Origin of osteoclasts: mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7260–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Islam S, Hassan F, Tumurkhuu G, Dagvadorj J, Koide N, Naiki Y, Yoshida T, Yokochi T. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand induces osteoclast formation in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells via augmented production of macrophage-colony-stimulating factor. Micrbiol Immunol. 2008;52:585–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lomaga MA, Yeh WC, Sarosi I, Duncan GS, Furlonger C, Ho A. TRAF6 deficiency results in osteoporosis and defective interleukin-1, CD40, and LPS signaling. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1015–1024. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakurai H, Chiba H, Miyoshi H, Sugita T, Yoriumi W. IκB kinases phosphorylated NF-κB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the trasactivation domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30353–30356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asagiri M, Sato K, Usami T, Ochi S, Nishina H, Yoshida H, Morita I, Wagner EF, Mak TW, Serfling E, Takayanagi H. Autoamplification of NFATc1 expression determines its essential role in bone homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1261–1269. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim K, Lee SH, Ha Kim J, Choi Y, Kim N. NFATc1 induces osteoclast fusion via up-regulation of Atp6v0d2 and the dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP) Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:176–185. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song I, Kim JH, Kim K, Jin HM, Youn BU, Kim N. Regulatory mechanism of NFATc1 in RANKL-induced osteoclast activation. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2435–2440. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu M, Moreno JL, Stains JP, Keegan AD. Complex regulation of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) expression by interleukin 4 (IL-4): IL-4 indirectly suppresses receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL)-mediated TRAP expression but modestly induces its expression directly. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32968–32979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halleen JM, Räisänen S, Salo JJ, Reddy SV, Roodman GD, Hentunen TA, Lehenkari PP, Kaija H, Vihko P, Väänänen HK. Intracellular fragmentation of bone resorption products by reactive oxygen species generated by osteoclastic tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1999;74:22907–22910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.22907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yagi M, Miyamoto T, Sawatani Y, Iwamoto K, Hosogane N, Fujita N. DC-STAMP is essential for cell–cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:345–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delaissé JM, Engsig MT, Everts V, del Carmen OM, Ferreras M, Lund L. Proteinases in bone resorption: obvious and less obvious roles. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;291:223–234. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(99)00230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang LC, Wu JB, Lu TJ, Lin WC. The prebiotic effect of Anoectochilus formosanus and its consequences on bone health. Brit J Nutr (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Katono T, Kawato T, Tanabe N, Suzuki N, Iida T, Morozumi A. Sodium butyrate stimulates mineralized nodule formation and osteoprotegerin expression by human osteoblasts. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53:903–509. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeder TM, Westendorf J. Histone deacetylase inhibitors promote osteoblast maturation. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2254–2263. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]