Abstract

The food choices in childhood have high a probability of being carried through into their adulthood life, which then contributes to the risk of many non-communicable diseases. Therefore, there is a need to gather some information about children's views on foods which may influence their food choices for planning a related dietary intervention or programme. This paper aimed to explore the views of children on foods and the types of foods which are usually consumed by children under four food groups (snacks, fast foods, cereals and cereal products; and milk and dairy products) by using focus group discussions. A total of 33 school children aged 7-9 years old from Selangor and Kuala Lumpur participated in the focus groups. Focus groups were audio-taped, transcribed and analyzed according to the listed themes. The outcomes show that the children usually consumed snacks such as white bread with spread or as a sandwich, local cakes, fruits such as papaya, mango and watermelon, biscuits or cookies, tea, chocolate drink and instant noodles. Their choices of fast foods included pizza, burgers, French fries and fried chicken. For cereal products, they usually consumed rice, bread and ready-to-eat cereals. Finally, their choices of dairy products included milk, cheese and yogurt. The reasons for the food liking were taste, nutritional value and the characteristics of food. The outcome of this study may provide additional information on the food choices among Malaysian children, especially in urban areas with regard to the food groups which have shown to have a relationship with the risk of childhood obesity.

Keywords: Diet, child, obesity, Malaysia, focus groups

Introduction

Childhood obesity is one of many public health concerns nowadays as it has been identified to increase the risk of getting other diseases in adulthood, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension and some cancers [1]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children is increasing in many countries around the world, including Malaysia. Also, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in primary school children increased significantly from 2002 to 2008. Furthermore, the prevalence of overweight children increased from 11.0% in 2002 to 12.8% in 2008. The same trend was shown in the prevalence of obesity where the prevalence increased from 9.7% in 2002 to 13.7% in 2008 [2]. A number of studies also demonstrated that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among urban school children was higher than that compared to rural school children [3,4].

The relationship between certain food groups and childhood obesity was studied extensively and it has been well-established. Snacks and fast foods consumption has been identified in contributing to the development of childhood obesity [5]. Previous studies suggested that dietary fibre may help protect against childhood obesity as dietary fibre affects food intake, digestion and absorption of nutrients and carbohydrate metabolism [6]. Cereal and cereal products are sources of dietary fibre as well as fruits, vegetables, legumes and other whole-grain products. Besides dietary fibre, several studies also suggest that dairy products may have favourable effects on body weight in children [7,8] and adults [9,10]. As the food groups above have potential effects on children's health, it is important for public health and education professionals to identify what types of foods in the food groups are actually consumed by children in order to develop interventions to encourage them to make better food choices and reduce the risk for chronic diseases.

Children's food choice is crucial as it becomes one of the determinants of their food intake, which then influence their nutritional status in terms of their development, growth and health. Their food choices in the early stage of life have a high probability to be carried through into adult life. The link between the diet during childhood and health in adulthood has been proven in many studies [11,12]. The diet during childhood contributes to the risk of disease in adult life such as coronary heart disease, cancer, stroke, hypertension and osteoporosis.

It is important to assess children's views on foods which may influence their food choices among children in Malaysia since there are only a scarce number of studies related to children's food choices that have been reported in this country. Most of the information of children's food choices was reported from the other countries outside Malaysia [13-17]. The information may not be applicable for Malaysian children due to the differences in eating patterns and food availability. Perhaps the types of foods commonly consumed by Malaysian children are already known, but not all of the food types have been documented. In addition, by having documented information on the food consumption of Malaysian children, it can be used as references for planning the related intervention and development of a dietary assessment method such as a food frequency questionnaire and dietary assessment aid such as food photographs specifically for Malaysian children.

There were several studies conducted to determine food consumption among children using either a qualitative or quantitative approach [13,17,18]. Qualitative research methodology has been used extensively in health and nutrition research. A focus group discussion is one type of qualitative methodology which has been applied widely in nutrition research. There were studies which applied focus group discussions to assess adolescents' perceptions about factors influencing their food choices and eating behaviour [19] as well as to explore the perceptions of physical activity and healthy eating among children [20]. This research method is also applied in studies to explore children's perspective on their everyday consumption of meals and snacks [21], and to explore the social and cultural influence on food intake [22].

However, there is a limited number of studies published on the application of focus group discussion in order to explore children's views on foods and to determine the foods usually consumed by children especially in Malaysia. The present study aimed to explore the children's views on foods and the types of foods which are usually consumed by the children under four food groups (snacks, fast foods, cereals and cereal products; and milk and dairy products) using qualitative methodology, specifically focus group discussions. Focus group discussions can be an effective method for obtaining data from special groups such as children who may have low literacy skills as the participants can use their own words in explaining and describing their views. Moreover, the qualitative method is applicable for this study as individual opinions are the main interest [23,24].

Subjects and Methods

Study design

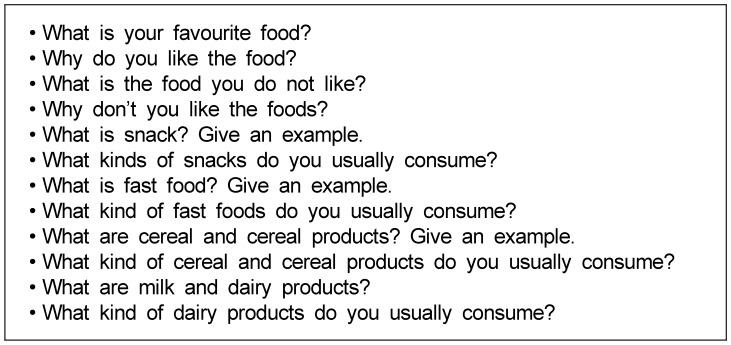

Five focus groups were conducted involving children aged 7-9 years old, who were divided into 5-10 participants per group. All the sessions were held at school during school hours. The focus group was conducted by a facilitator and assisted by a scribe who took field notes throughout the discussion. The discussion was conducted in Malay language and followed the procedures in the Facilitator's Guides booklet which was prepared by the research team. Before the discussion session started, the facilitator and scribe introduced themselves to the participants and started the ice-breaking session in which each of the participants were asked to briefly introduce themselves. Then, the session proceeded with the introduction to the study where the facilitator briefly explained the aims of the focus group, the rules in the focus group and the confidentiality of the outcome from the focus group. The participants were also informed that the discussion will be audio-taped for the purpose of data analysis. After the introduction, the discussion session began by asking semi-structured and open-ended questions. The questions for the focus group are listed in Fig. 1. Each focus group took about 75 minutes and was conducted by the same two researchers. The study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia.

Fig. 1.

Questions for focus group discussions

Participants

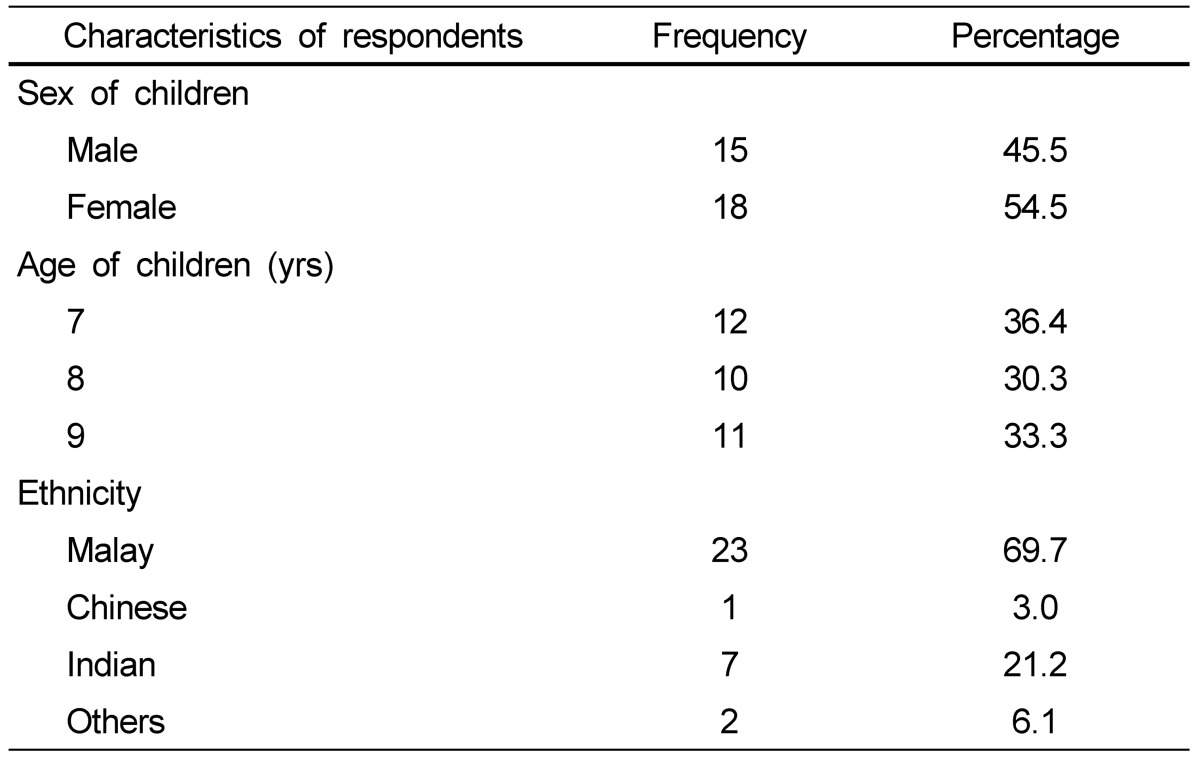

Participants for the focus group were recruited from two primary schools in the urban area of Selangor and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The schools were drawn randomly from a list of urban schools in Selangor and Kuala Lumpur which were obtained from the website of the Department of Education from both states, respectively. The parents of eighty children in Year 1 to Year 3 (7-9 years old) in both schools were given a letter informing them about the study and asked their permission to allow their children to participate in the focus group discussion. From the total parents invited, 37 consents were obtained (46%). A total of 33 children participated in the focus group and the remaining 4 children were not present on the day the focus group was conducted. The characteristics of participants by sex, age and ethnicity are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents by sex, age and ethnicity (n = 33)

Data analysis

Analysis of the data was based on the questions asked during the focus groups. Focus groups were audio-taped with prior consent from the participants and transcribed while referring to the field notes which were taken by the scribe. The audiotapes were then listened to again in order to identify responses for every question. After the analysis process was completed, the outcomes were organized into themes based on the response from participants as below:

Favourite and non-favourite food

Reasons of food liking

Consumption of snacks, fast foods, cereals and cereal products and dairy products

Knowledge about snacks, fast foods, cereals and cereal products and dairy products

Results

Favourite and non-favourite food

Most of the interviewed children (n = 20, 60.6%) like to eat cereal and cereal products. The children like to eat various types of rice for example white rice or in combination with other dishes such as chicken, fish and vegetables like water spinach, carrot, spinach, long bean, cucumber and cabbage. The other types of rice were nasi lemak (rice cooked with coconut milk served with anchovy, chilli paste and boiled egg), chicken rice (rice served with steamed or fried chicken and chicken soup) and fried rice. Their favourite cereal products were ready-to-eat cereals with milk, fried kuehteow, fried vermicelli, white bread and instant noodles. Furthermore, they also like to eat fast foods including nuggets, fried chicken, pizza and burgers. Some types of fruits such as apple, mango and also salad (mixture of fruits and vegetables) were also popular among the children. On the other hand, some of the children dislike ice cream, chocolate, sweets, fish, fruits such as oranges, papaya, bananas, water melon and rose apples and also vegetables such as pumpkin and cucumber.

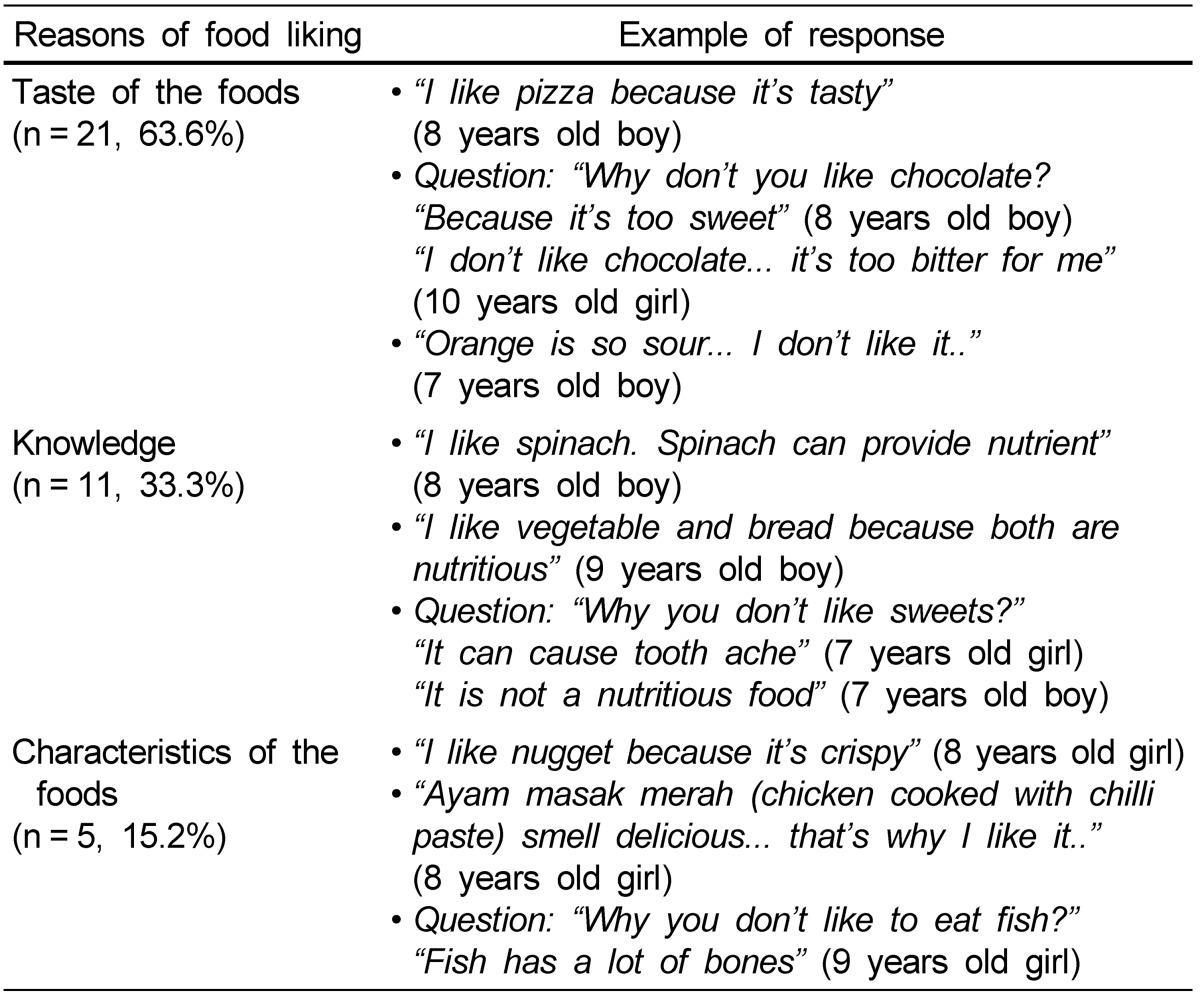

Reasons of food liking

There were several reasons why they like and dislike certain foods. One of the reasons was the taste of the foods. Some of them (n = 11, 33.3%) like or dislike the food because of their knowledge that the foods are nutritious and good for their health or the foods are not nutritious and can cause illness. Furthermore, the other reason for liking a particular food is the characteristics of the foods such as crispiness and smell. The examples of responses for the reasons of liking a particular food are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reasons of food liking among interviewed children and the number of children responded to the respective reasons

Consumption of snacks, fast foods, cereals and cereal products and dairy products

The children usually consumed snacks between breakfast and lunch and between lunch and dinner. Between breakfast and lunch, they consumed white bread with peanut butter, kaya (spread made from coconut) and sardines as sandwiches, local cakes, such as karipap (curry puff) and local doughnut and fruits such as papaya, mango and watermelon. The types of foods they consumed between lunch and dinner were biscuits or cookies, tea, chocolate drink and instant noodle. For fast foods, the children usually consumed pizza, burgers, French fries and fried chicken. The types of cereal and cereal products which they frequently consumed were rice, bread and ready-to-eat cereals such as Koko Crunch, Honey Star and cornflakes. The children also frequently consumed milk and other dairy products like cheese and yogurt with various flavours such as strawberry, grape and mango. The examples of responses for the types of snacks, fast foods, cereal products and dairy products consumed among interviewed children are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Types of snacks, fast foods, cereal products and dairy products consumed among interviewed children

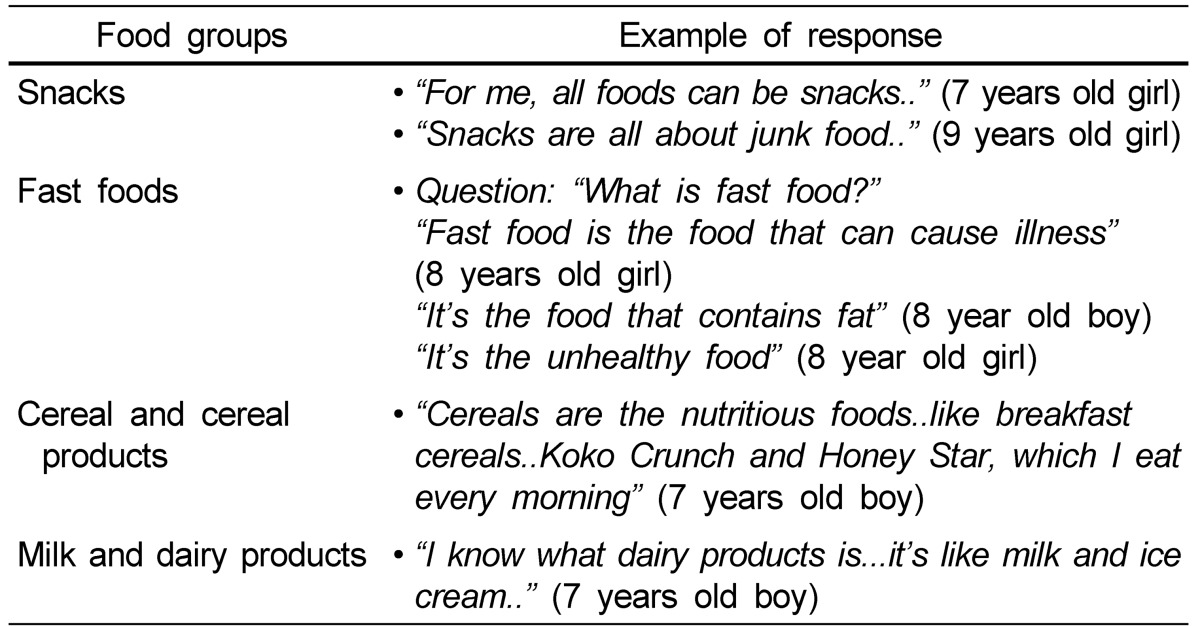

Knowledge about snacks, fast foods, cereals and cereal products and dairy products

When the children were asked about the definition of a snack, they had no idea what a snack is. Some of them think that all snacks are unhealthy, but the fact is snacks can be healthy and unhealthy depending on the choice of food. They listed keropok (local crisp made of shrimp/ fish and rice flour), instant noodles, potato chips and junk food as examples of snacks. For fast foods, children aged 7 years old cannot give the definition of fast food and gave wrong examples of fast food such as fruits and vegetables. On the other hand, older children gave some ideas about what fast food is. When they were asked about cereal and cereal products, most of them did not know what cereal and cereal products are. Only one gave an opinion about cereals. After explaining the definition of cereal and cereal products to them, they were able to give several examples of cereal brands such as Koko Crunch, Honey Star and Nestum. Finally, for milk and dairy products, most of the children do not know what a dairy product is. Only one gave an opinion. The examples of responses for the knowledge about snacks, fast foods, cereal products and dairy products among interviewed children are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Knowledge about snacks, fast foods, cereals and cereal products and dairy products among interviewed children

Discussion

In this study, we found that most of the children like food because of the taste. The other reasons are because the food is nutritious and the attractive characteristics of the food such as a nice smell and the foods texture, for example the crispiness. Previous studies have shown that the taste of food emerged as a major limiting factor related to consumption [25] and children's liking of the taste of a product has been identified as the most important determinant of children's food choice [26-28]. Besides taste, the appearance, the smell and the way the food is prepared or served contribute to the most important influence on food choice among adolescents [19].

Most of the interviewed children like to eat rice. In Malaysia, rice is the staple food and is one of the main energy sources for Malaysian people. It is usually consumed twice daily as lunch and dinner, served and consumed in many ways of cooking with a variety of dishes. This outcome is not surprising because the liking for some foods or products can be increased after repeated exposure and this is also shown in a previous study [29]. Salad, the mixture of various types of fruits and/or vegetables mixed together with small amounts of condiments such as mayonnaise is also one of their favourite foods. They informed that their mother usually prepared salad at home. As we know, salad is easy to prepare and this is the convenient way to prepare the food for working parents.

The children also like ready-to-eat cereals, such as cornflakes which is usually consumed during breakfast. They like to eat fried kuehteow and fried vermicelli, which can be easily bought from restaurants or hawker stalls. Some of the children also like to eat fast foods such as instant noodles, nuggets, fried chicken, pizza and burgers. The children still consumed the fast foods despite acknowledging that it is unhealthy and is not good to consume frequently. Only a few of them like to eat fruits such as apples and mangos and vegetables such as water spinach, carrots, spinach, long beans, cucumbers and cabbage. They like to eat fruits and vegetables not only because of the taste but also because they know that vegetables are nutritious and good for their health. A previous study also showed this positive outcome in which children were eating fruits and vegetables for their general health or for specific nutrients or benefits [25].

For non-favourite food, interestingly, some children also dislike some types of foods when they know that the food is not good for their health for example chocolate, sweets and ice cream. The children do not like sweets as they know it can cause tooth aches. This shows that intervention can be carried out to decrease the intake of non-healthy foods and increase the intake of healthy foods by explaining to them the long-term benefits and consequences of over-consuming such types of foods. This outcome also shows that the children did not only choose or avoid foods based on their contents, but they also consider it based on their basic knowledge on the health-related effect of consuming the foods. However, they do not like some types of fruits such as oranges, papayas, bananas, watermelon and rose apples. One interviewed child did not like fish because of the characteristics of fish with lots of bones.

In this study, we defined snacks based on the time criterion. Food considered as meals are the foods consumed between 8 and 10 am, between 12 and 2 pm, and between 6 to 8 pm. Any food item consumed between the meals is considered to be a snack [30]. Snacking can be an important way to meet the energy and nutrient needs of growing children or it can lead to excess energy intake [31]. Most of the children interviewed take nutritious snacks. They usually consumed snacks between breakfast and lunch in school during recess time at about 10 to 10.30 am. Some of them brought food from home such as bread and sandwiches and some children buy them at the school canteen for example fruits and local cakes.

For the children who attend the morning school session, they usually consume snacks in the evening at home and vice versa. They usually consume biscuits or cookies with tea or chocolate drinks as evening snacks. The types of snacks which we found in the study were quite similar to the previous findings [18] which reported that the usually consumed snacks among children and adolescents were keropok (local crisp made of shrimp or fish and rice flour), biscuits and bread followed by some local cakes. The children also think that all snacks are always unhealthy food, but the fact is snacks can be nutritious or non-nutritious depending on the types of food chosen. Snacks can be classified based on food categories by their quality and composition. Snacks are usually classified as high quality, for example an apple and a glass of milk; or low or no quality, such as ice cream and sweets [32].

Western fast foods are very popular among the children interviewed. They usually consume fast foods such as pizza, burgers, French fries and fried chicken. The reason why they can usually consume these foods is because the foods are easily accessed either in the school or at home. French fries and fried chicken for instance can be bought from the school canteen or can be prepared at home using frozen processed fries and chicken. Younger children did not have any idea about fast food, while older children could give some idea about what fast food is. However, all of them only have negative ideas about fast food including how fast foods can cause bad effects to their health, contains high fat and is unhealthy. This shows that they are quite exposed to the fact that most of the fast foods are not good for their health.

Some of the children usually consumed fast foods at fast food restaurants with their family during weekends. A previous study has shown that around 60-70% of children consumed fast food and local hawker food in a week [18]. The consumption of fast foods in children have to be controlled as the previous study reported that those who consumed fast foods more than four times a week were more likely to be overweight and obese (24%) than those who consumed fast foods less than four times a week (20%) in the sample of primary school children aged 9 to 10 years old in Selangor, Malaysia [5].

Interviewed children also consumed cereals as their main meals (breakfast, lunch and dinner) and snacks. They usually eat ready-to-eat cereal during breakfast while rice is consumed everyday during lunch and dinner. Maybe ready-to-eat cereals are a popular choice of breakfast meals because they are fast and easy to prepare and consumed in the morning. The convenience of food has been identified as one of the most important factors perceived as influencing food choices in adolescents [19]. In addition, the advantage of having cereals for breakfast was reported in a study that showed children who skipped breakfast or ate non-cereal breakfast foods had a significantly higher mean body mass index and blood cholesterol level than children who ate breakfast, especially ready-to-eat cereals [33]. This is because breakfast cereal is usually lower in fat and higher in fibre than a non-cereal breakfast, therefore this finding suggests that high-fibre and low-fat meals may help protect against childhood obesity. As discussed previously, cereal and cereal products such as rice and bread are one of the main energy sources for Malaysian people. Besides, cereal is also an important source of dietary fibre, along with fruits, vegetables, legumes and other whole-grain products [34].

Milk and other dairy products are among the best natural sources of calcium. Almost all of the children interviewed consumed milk every day during breakfast and supper. Based on a previous study, eating breakfast has a positive impact on milk intake and increases calcium intake [35]. Most of the children interviewed consumed ready-to-eat cereals with milk as their breakfast. This has been studied in the Bogalusa Heart Study, whereby most of the 10-year-old children (96%) who consumed ready-to-eat cereals also consumed an item from the milk group [35]. Only a small number of children said that they usually consume cheese and yogurt.

There are some limitations in the present study. Firstly, this study may not be generalized for all Malaysian children as the study takes part in only urban areas of Selangor and Kuala Lumpur with only 7-9 years old children and the proportion of the participants are not divided according to the proportion of Malaysian children. In future studies, it is recommended to expand the framework to both urban and rural areas to obtain a better understanding of the food intake of Malaysian children. Finally, the interviewed children are quite young and this may affect the reliability of their report. For future studies, it is suggested to interview parents, children and also school canteen operators to gather better information about the availability of foods in the school and home environment and the children's food choices in both settings.

The present study shows that children's preferences of food depend on several factors such as the taste, nutritional value and characteristics of the food. Therefore, in order to promote healthy food to children the food manufacturer should produce healthy foods with good taste and an attractive presentation which is child-friendly. Also, parents and teachers should educate the children about healthier food choices, as they might be interested in the food after they know the nutritional value of the food. Parents have an important role in providing healthy foods and snacks for their children at home. Schools also have to provide the best environment for promoting fruits as snacks. Furthermore, it is very important to promote the intake of fruits and vegetables as snacks because they do not only satisfy the appetite but are also nutritious. The outcome of this study may provide additional information on the children's views on foods and the consumption of selected food groups among Malaysian children, especially in urban areas with regard to the food groups which have shown to have a relationship with the risk of childhood obesity. Moreover, the outcome from this study may be useful for future research in planning a related intervention or health programme in order to improve the eating habits of children.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to convey appreciation to Wong Yoke Wei and Abdul Hafiz Abdul Rahman for assistance in field work. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Ministry of Education of Malaysia, Department of Education of Selangor and Kuala Lumpur and all the teachers and students who participated in this study.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) (Project No.: 05-10-07-281 FR).

References

- 1.Stewart L. Childhood obesity. Medicine. 2011;39:42–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ismail MN, Ruzita AT, Norimah AK, Poh BK, Nik Shanita S, Nik Mazlan M, Roslee R, Nurunnajiha N, Wong JE, Nur Zakiah MS, Raduan S. Prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity in two cross-sectional studies of Malaysian children, 2002-2008; Proceedings of the MASO 2009 Scientific Conference on Obesity: Obesity and Our Environment; 2009 August 12-13; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 2009. pp. 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tee ES, Khor SC, Ooi HE, Young SI, Zakiyah O, Zulkafli H. Regional study of nutritional status of urban primary schoolchildren. 3 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Food Nutr Bull. 2002;23:41–47. doi: 10.1177/156482650202300106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khor GL, Noor Safiza MN, Rahmah R, Jamaluddin AR, Kee CC, Geeta A, Jamaiyah H, Suzana S, Wong NF, Ahmad Ali Z, Ruzita AT, Ahmad Faudzi Y. The Third National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS III) 2006. Nutritional status of children aged 0 to below 18 years; Proceedings of the 23rd Scientific Conference of the Nutrition Society of Malaysia, Holistic Approach to Nutritional Wellbeing; 2008 March 27-28; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaini MZ, Lim CT, Low WY, Harun F. Factors affecting nutritional status of Malaysian primary school children. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2005;17:71–80. doi: 10.1177/101053950501700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali R, Staub H, Leveille GA, Boyle PC. Dietary fiber and obesity: a review. In: Vahouny GV, Kritchevsky D, editors. Dietary Fiber in Health and Disease. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skinner J, Carruth B, Coletta F. Does dietary calcium have a role in body fat mass accumulation in young children. Scand J Nutr. 1999;43:45S. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carruth BR, Skinner JD. The role of dietary calcium and other nutrients in moderating body fat in preschool children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:559–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies KM, Heaney RP, Recker RR, Lappe JM, Barger-Lux MJ, Rafferty K, Hinders S. Calcium intake and body weight. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4635–4638. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heaney RP, Davies KM, Barger-Lux MJ. Calcium and weight: clinical studies. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:152S–155S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maynard M, Gunnell D, Emmett P, Frankel S, Davey Smith G. Fruit, vegetables, and antioxidants in childhood and risk of adult cancer: the Boyd Orr cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:218–225. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ness AR, Maynard M, Frankel S, Smith GD, Frobisher C, Leary SD, Emmett PM, Gunnell D. Diet in childhood and adult cardiovascular and all cause mortality: the Boyd Orr cohort. Heart. 2005;91:894–898. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.043489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douglas L. Children's food choice. Nutr Food Sci. 1998;1:14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W, Ziegler PJ. Children's food preferences: a longitudinal analysis. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1638–1647. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell AC, Swinburn BA. What are the key food groups to target for preventing obesity and improving nutrition in schools? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:258–263. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooke LJ, Wardle J. Age and gender differences in children's food preferences. Br J Nutr. 2005;93:741–746. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiates GM, Amboni RD, Teixeira E. Television use and food choices of children: qualitative approach. Appetite. 2008;50:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moy FM, Gan CY, Siti Zaleha MK. Eating pattern of school children and adolescents in Kuala Lumpur. Malays J Nutr. 2006;12:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C, Casey MA. Factors influencing food choices of adolescents: findings from focus-group discussions with adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:929–934. 937. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gosling R, Stanistreet D, Swami V. 'If Michael Owen drinks it, why can't I?'- 9 and 10 year olds' perceptions of physical activity and healthy eating. Health Educ J. 2008;67:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husby I, Heitmann BL, O'Doherty Jensen K. Meals and snacks from the child's perspective: the contribution of qualitative methods to the development of dietary interventions. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:739–747. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolaou M, Doak CM, van Dam RM, Brug J, Stronks K, Seidell JC. Cultural and social influences on food consumption in Dutch residents of Turkish and Moroccan origin: a qualitative study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betts NM, Baranowski T, Hoerr SL. Recommendations for planning and reporting focus group research. J Nutr Educ. 1996;28:279–281. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krueger RA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molaison EF, Connell CL, Stuff JE, Yadrick MK, Bogle M. Influences on fruit and vegetable consumption by low-income black American adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2005;37:246–251. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson CM, Gemmill KP. Association of sweet preference and food selection among four to five year old children. Ecol Food Nutr. 1981;11:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pérez-Rodrigo C, Ribas L, Serra-Majem L, Aranceta J. Food preferences of Spanish children and young people: the enKid study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(Suppl 1):S45–S48. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricketts CD. Fat preferences, dietary fat intake and body composition in children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51:778–781. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liem DG, de Graaf C. Sweet and sour preferences in young children and adults: role of repeated exposure. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toornvliet AC, Pijl H, Hopman E, Elte-de Wever BM, Meinders AE. Serotoninergic drug-induced weight loss in carbohydrate craving obese patients. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:917–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adair LS, Popkin BM. Are child eating patterns being transformed globally? Obes Res. 2005;13:1281–1299. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wurtman J, Wurtman R, Berry E, Gleason R, Goldberg H, McDermott J, Kahne M, Tsay R. Dexfenfluramine, fluoxetine, and weight loss among female carbohydrate cravers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:201–210. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Resnicow K. The relationship between breakfast habits and plasma cholesterol levels in schoolchildren. J Sch Health. 1991;61:81–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1991.tb03242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams CL. Importance of dietary fiber in childhood. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:1140–1146. 1149. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00307-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicklas TA, O'Neil CE, Berenson GS. Nutrient contribution of breakfast, secular trends, and the role of ready-to-eat cereals: a review of data from the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:757S–763S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.4.757S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]