Abstract

Background

Filaggrin (FLG) has a central role in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis (AD). FLG is a complex repetitive gene; highly population-specific mutations and multiple rare mutations make routine genotyping complex. Furthermore, the mechanistic pathways through which mutations in FLG predispose to AD are unclear.

Objectives

We sought to determine whether specific Raman microspectroscopic natural moisturizing factor (NMF) signatures of the stratum corneum could be used as markers of FLG genotype in patients with moderate-to-severe AD.

Methods

The composition and function of the stratum corneum in 132 well-characterized patients with moderate-to-severe AD were assessed by means of confocal Raman microspectroscopy and measurement of transepidermal water loss (TEWL). These parameters were compared with FLG genotype and clinical assessment.

Results

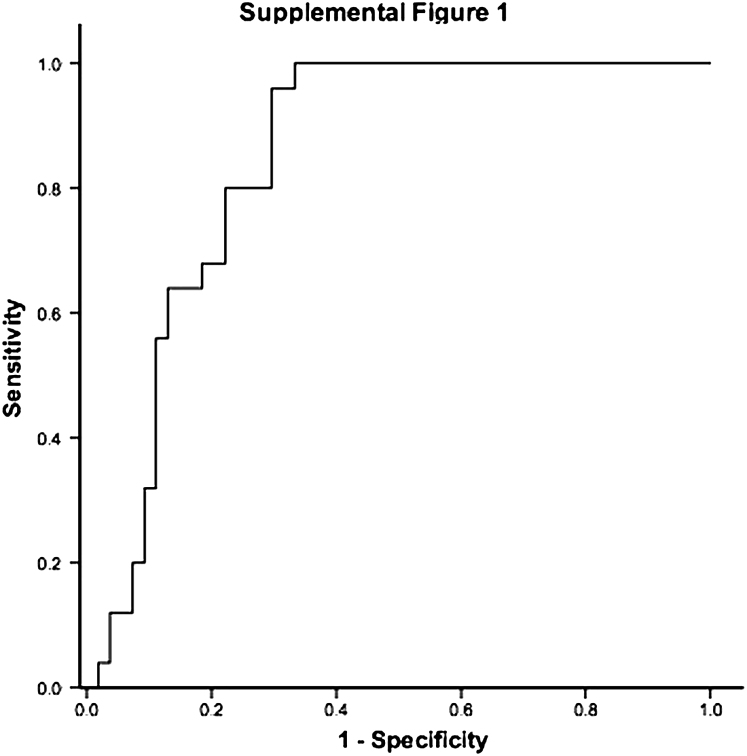

Three subpopulations closely corresponding with FLG genotype were identified by using Raman spectroscopy. The Raman signature of NMF discriminated between FLG-associated AD and non–FLG-associated AD (area under the curve, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91-0.99). In addition, within the subset of FLG-associated AD, NMF distinguished between patients with 1 versus 2 mutations. Five novel FLG mutations were found on rescreening outlying patients with Raman signatures suggestive of undetected mutations (R3418X, G1138X, S1040X, 10085delC, and L2933X). TEWL did not associate with FLG genotype subgroups.

Conclusions

Raman spectroscopy permits rapid and highly accurate stratification of FLG-associated AD. FLG mutations do not influence TEWL within established moderate-to-severe AD.

Key words: Atopic dermatitis, confocal Raman spectroscopy, eczema, filaggrin, hyperlinearity, natural moisturizing factor, transepidermal water loss, tyrosine

Abbreviations used: AD, Atopic dermatitis; AUC, Area under the curve; FLG, Filaggrin; HLP, Hyperlinear palms; NMF, Natural moisturizing factor; ROC, Receiver operating characteristic; SC, Stratum corneum; TEWL, Transepidermal water loss

Discuss this article on the JACI Journal Club blog: www.jaci-online.blogspot.com.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a complex and heterogeneous inflammatory skin disease driven and modified by immunologic, environmental, and genetic factors.1,2 The identification of filaggrin (FLG) null alleles in up to 50% of patients with moderate-to-severe AD implicates a fundamental role for barrier homeostasis in this disease.3-6 Although the mechanisms leading to AD in FLG mutation carriers are unclear, the deficiency of FLG likely facilitates permeability of biologically active allergens and microbial colonization that subsequently trigger inflammatory cascades.7 The recent identification of a murine model for FLG deficiency, with the detection of a homozygous frameshift mutation in the Flg gene in flaky tail mice, should accelerate our understanding of pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic intervention points in patients with AD.8

Knowledge of the biochemical functions of filaggrin and its breakdown products indicate that a quantitative variation in gene or protein dosage might be relevant in determining phenotype.9,10 Filaggrin is initially produced as profilaggrin, a large, insoluble, heavily phosphorylated protein consisting of 10 to 12 tandem repeats of filaggrin units separated by short hydrophobic linker peptides.11,12 In the transitional layer profilaggrin is dephosphorylated and proteolytically processed into its functional filaggrin units, which bind to and collapse the keratin cytoskeleton and other intermediate filaments, acting as a scaffold for the subsequent reinforcement steps of the stratum corneum (SC).13-15 Subsequently, filaggrin is progressively degraded within the SC into a pool of hygroscopic amino acids, including pyrrolidone carboxylic acid, urocanic acid, and alanine. This composite mixture of amino acids and their derivatives, together with specific salts and sugars, form the natural moisturizing factor (NMF).16,17

NMF is highly hygroscopic and plays a central role in maintaining hydration of the SC and is additionally proposed to have a significant role in maintenance of the pH gradient of the skin, cutaneous antimicrobial defense, and regulation of key enzymatic events in the SC.18,19 Filaggrin thus has complex functions, with roles in establishing structural and chemical barrier function, hydration, and maintenance of epidermal homeostasis in the face of continuous transformation.20 Expression of filaggrin and subsequent breakdown of filaggrin into NMF is additionally determined based on properties of the microenvironment, including local pH, relative humidity, and protease activity.17,21,22In vitro evidence also indicates that filaggrin skin expression might be modulated by the atopic inflammatory response mediated by the cytokines IL-4 and IL-13.23 Genetically determined modifiers of protein dosage include the copy number of filaggrin repeat units, which vary in the population from 10 to 12 units and segregate by normal Mendelian genetic mechanisms.11,24 These genetic polymorphisms reflect tandem duplications of FLG repeats 8, 10, or both and might be an additional modifier of disease phenotype in heterozygotes who carry longer-sized variants on the unaffected allele.25 Our early data suggest that NMF levels correlate with FLG-null allele status and might therefore directly contribute to the dry skin phenotype seen in both patients with ichthyosis vulgaris and those with AD.10

Raman spectroscopy is capable of measuring in vivo information regarding the molecular composition of the skin, including quantitative analysis of amino acids and water content. It is based on the inelastic light scattering, or Raman scattering, of monochromatic light when the frequency of photons, usually from a laser source, changes on interaction with a sample, giving rise to characteristic Raman spectra and providing noninvasive real-time signatures of biological samples at a molecular level.

We sought to determine whether specific Raman NMF signatures of the SC could be used as markers of FLG genotype in patients with moderate-to-severe AD. We examined the association of NMF estimation with clinical evidence of hyperlinear palms (HLP), a clinical sign that has been shown to be associated with FLG mutations in previous studies. We also sought to examine the effects, within patients with moderate-to-severe AD, of FLG genotype on transepidermal water loss (TEWL) as a measure of an inside-out barrier defect.

Methods

Following standard genetic practice, in this article FLG−/− designates a patient homozygous for null alleles (ie, 2 null alleles), FLG+/− designates a heterozygote null allele/wild-type (ie, 1 null allele), and FLG+/+ designates a homozygote wild-type (ie, 0 null alleles). A further abbreviation describes patients with AD with FLG mutations (FLG+/− and FLG−/−) as ADFLG and those without FLG mutations (ie, FLG+/+) as ADNON-FLG.

One hundred thirty-five unrelated Irish children with a history of moderate-to-severe AD were recruited from dedicated tertiary referral AD clinics. Diagnosis was made by experienced pediatric dermatologists according to the United Kingdom diagnostic criteria.26 Exclusion criteria from the study were patients who had received systemic therapy, such as corticosteroids or immunosuppressants, in the preceding 3 months and patients whose ancestry was not exclusively Irish (4/4 grandparents). Detailed phenotypic data were collected. The Nottingham Eczema Severity Score27 was selected as an estimate of disease severity. Given previous publications and our own clinical experience of noting palmar hyperlinearity, this clinical sign was scored by using an investigator assessment of 0 (no hyperlinearity), 1 (mild/subtle hyperlinearity), and 2 (severe hyperlinearity).

Genetic screening

All patients were screened for the 6 most prevalent FLG mutations in the Irish population (R501X, 2282del4, R2447X, S3247X, 3702delG, and Y2092X), as previously described.28 Full sequencing of FLG was performed as detailed previously.28 Based on screening for these 6 prevalent FLG mutations, 58.3% were carriers of 1 or more FLG mutations (15.1% FLG−/−, 43.2% FLG+/−, and 41.7% FLG+/+). An additional rare mutation was known to be present in 1 subject in a heterozygous state (R1474X). Additional screening was performed by means of complete sequencing of the FLG gene in selected subjects, as previously described.29 The entire collection was then rescreened for these 5 novel mutations found on complete sequencing.

Biophysical analysis of the SC

Skin biophysical measurements were performed under standardized conditions (room temperature, 22 °C-25 °C; humidity levels, 30% to 35%). Before measurements, patients were acclimatized for a minimum of 10 minutes. All measurements were performed by one of 2 investigators (G.M.O. and P.M.J.H.K.). Topical therapies, including emollients, were withheld from the measurement sites for 48 hours preceding the study. TEWL was measured on nonlesional skin of the extensor forearm (Tewameter 300; Courage and Khazaka Electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany).

NMF was measured in the SC of the thenar eminence by using confocal Raman microspectroscopy (model 3510 Skin Composition Analyzer; River Diagnostics, Rotterdam, The Netherlands). The principles of this method and the procedure have been described elsewhere.30,31 Depth profiles of Raman spectra were measured at 5-μm intervals from the skin surface at 30, 35, 40, 45 and 50 μm below the skin surface. An average of 8 profiles (totaling to 40 Raman spectra) from different areas of the thenar eminence were measured per patient. Raman spectra were recorded in the spectral region at 400 to 1,800 cm−1 with a 785-nm laser. Laser power on the skin was 25 mW. Levels of skin constituents relative to keratin were determined from the Raman spectra by means of classical least-squares fitting. Details of the method have been described elsewhere.30,31 Briefly, reference spectra of keratin, NMF, urocanic acid, lactate, urea, ceramide, and cholesterol were fitted to the individual Raman spectra from the skin. The combination of these reference spectra provides an adequate model for in vivo Raman spectra of normal human SC. A spectrum of reagent-grade L-tyrosine (Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) was added to this set of reference-fit spectra to enable determination of increased tyrosine levels. The resulting fit coefficients represent the relative proportions in which the skin constituents contribute to the total Raman skin spectrum. The reference spectrum of NMF had been constructed from the weighted sum of the spectra of its dominant constituents (pyrrolidone carboxylic acid, ornithine, serine, proline, glycine, histidine, and alanine). All concentrations of skin constituents relative to keratin were calculated from the recorded Raman spectra by using SkinTools 2.0 (River Diagnostics B.V., Rotterdam, The Netherlands); NMF levels derived from the individual Raman spectra were used to assess intrapatient variation in NMF. These NMF levels were then averaged to obtain the mean NMF level per patient. Of the 135 subjects who participated in the study, 3 patients were unable to fully cooperate with the Raman measurement, and their results were excluded because of insufficient spectra collection.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Our Lady's Children's Hospital, Dublin. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their parents.

Statistical methods

Patients were characterized, a priori, into 3 genotypes (FLG+/+, FLG+/−, and FLG−/−), as described in the methods. The designation FLG-associated AD (ADFLG) includes those with 1 or 2 FLG mutations (FLG+/− and FLG−/−), whereas non–FLG-associated AD (ADNON-FLG) are FLG+/+. The data were characterized as having either a normal or a skewed distribution. Positively skewed data were log transformed. Box and whiskers plots showing the median value with interquartile range (25th-75th box length) of variables were constructed for the 3 FLG genotypes (FLG−/−, FLG+/−, and FLG+/+). ANOVA was used to compare means among the 3 genotype subgroups and presented as means with SDs and 95% CIs. Homogeneity of variances was tested by using the Levine statistic. A post hoc Tukey analysis for multiple comparisons was performed to examine pairwise differences among the 3 genotype subgroups. Mean differences for each pairwise comparison was presented together with a 95% CI of the mean difference.

Nonparametric receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, which plot sensitivity against 1−specificity, were constructed to examine the utility of Raman spectroscopy to, in the first instance, differentiate between ADFLG and ADNON-FLG. We then sought to further determine whether, within the FLG-associated AD group, ROC curve analysis could determine an NMF cutoff point to predict homozygous or heterozygous subjects (FLG−/− vs FLG+/−). Areas under the curve (AUCs) with 95% CIs are presented. The cutoff for maximal sensitivity and specificity was deduced from the graphic output. Sensitivity and specificity for our dataset, based on the ROC output, are also presented to provide a preliminary indication of the clinical utility of Raman spectroscopy as a novel technique to distinguish FLG genotypes in patients with AD. However, further evaluation of Raman spectroscopy will be required in different well-characterized populations of patients with AD and healthy subjects.

HLP was scored clinically as absent (0) mild (1), or severe (2). For statistical analysis, HLP was dichotomized to no evidence of hyperlinearity (clinical score 0) versus any hyperlinearity (clinical scores of 1 or 2). The κ statistic was used to measure agreement between clinical scores of HLP and an NMF cutoff of 1.07. Where the observed agreement between scores is better than the degree of agreement expected by chance alone, κ is scored from 0 to 1.0, with 1.0 representing perfect agreement. A κ value of less than 0.2 is poor, a score of 0.2 to 0.4 is fair, 0.4 to 0.6 is considered moderate agreement, 0.6 to 0.8 is considered good agreement, and greater than 0.8 is considered excellent agreement.32 Data were analyzed with SPSS software (version 15; SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Ill). Significance was set at the 5% level.

Results

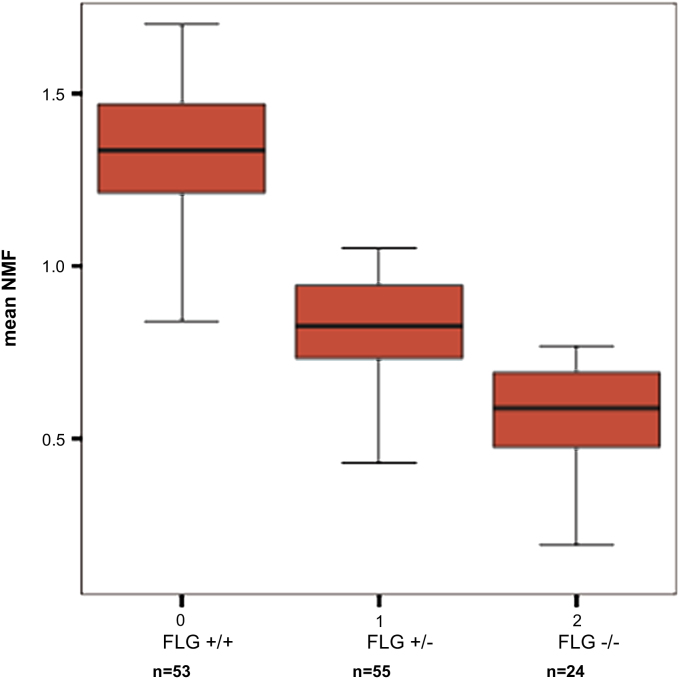

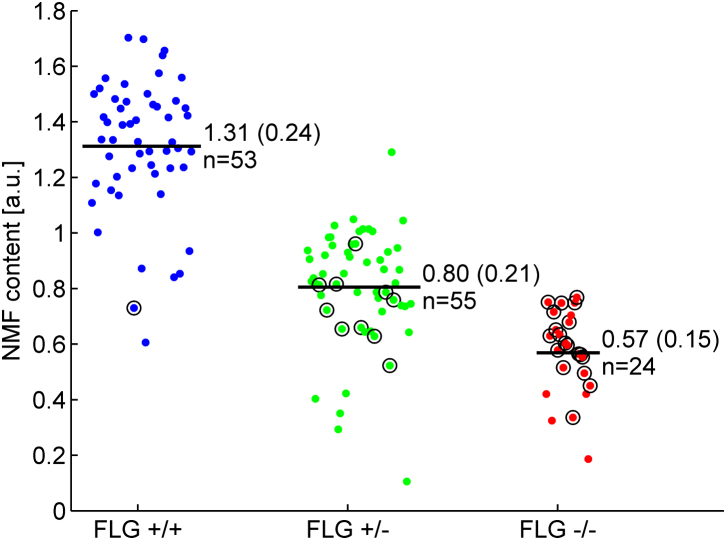

Clinical characteristics and summary data of the study cohort are outlined in Table I. NMF levels assessed by means of Raman spectroscopy for subjects according to final FLG genotype (final genotype after full screening) are shown in Fig 1. In each pairwise comparison of the 3 genotypes, there is a statistically significant difference in NMF values (P < .001, ANOVA, Tukey post hoc analysis; Table II). IgE levels were not normally distributed. After log transformation of IgE data, there was no statistically significant difference in IgE values among the 3 FLG mutation subgroups (P < .48, Table I).

Table I.

Cohort characteristics according to final genotype

| Final FLG genotype∗† |

All mutations combined, no. (%) |

Age (y), mean (SD) |

Male sex, no. (%) |

NESS,‡ mean (SD) |

Palmar hyperlinearity score‡ |

TEWL (g/m2/h), mean (SD) |

NMF (AU), mean (SD) |

Tyrosine peaks, no. (%) |

Log IgE# mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened§ | n = 132 | n = 132 | n = 132 | n = 132 | n = 131 | n = 102 | n = 132 | n = 132 | n = 129 |

| +/+ | 53 (40.15) | 8.43 (3.76) | 32 (60.3) | 12.40 (2.39) | 0: 36 | 15.54 (9.34), n = 41 | 1.31 (0.24) | 1 (1.89) | 6.89 (2.29) |

| 1: 10 | |||||||||

| 2: 7 | |||||||||

| n = 53 | |||||||||

| +/− | 55 (41.66) | 8.2 (4.12) | 32 (58.2) | 11.28 (2.80) | 0: 8 | 15.59 (6.72), n = 44 | 0.80 (0.21) | 10 (18.18) | 6.56 (1.78) |

| 1: 23 | |||||||||

| 2: 23 | |||||||||

| n = 54 | |||||||||

| −/− | 24 (18.18) | 8.83 (4.16) | 15 (62.5) | 12.13 (2.52) | 0: 0 | 17.35 (7.37), n = 17 | 0.57 (0.15) | 19 (79.16) | 7.11 (1.50) |

| 1: 1 | |||||||||

| 2: 23 | |||||||||

| n=24 | |||||||||

| P value | − | .84‖ | .97¶ | .07‖ | − | .70‖ | <.0001‖ | <.0001¶ | .48‖ |

AU, Arbitrary units.

Final FLG status after rescreening cohort for all mutations (FLG status before detection of novel mutations: FLG+/+, 41.7%; FLG+/−, 43.2%; and FLG−/−, 15.1%).

+/+, No FLG mutation; +/−, 1 FLG mutation; −/−, 2 FLG mutations.

NESS, Nottingham Eczema Severity Score. Palmar hyperlinearity score: 0, no hyperlinearity; 1, intermediate; 2, marked.

Hyperlinearity scoring and TEWL data are not available for 1 and 30 subjects, respectively.

Comparison of means among the 3 groups of FLG mutations using ANOVA.

Comparison of proportions using χ2 test for comparison of a 2 × 3 contingency table.

IgE data were positively skewed. The mean of the log-transformed data is presented.

Fig 1.

Box and whiskers plot of NMF by FLG genotypes (final genotype after full screening) showing the median (midline) and interquartile range corresponding to the length of the box.

Table II.

ANOVA showing a statistically significant difference in NMF among the 3 FLG genotype subgroups together with 95% CIs

| Genotype | No. | Mean NMF | 95% CI | Comparison genotype | Mean difference | 95% CI mean difference | P value∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLG+/+ | 53 | 1.31 ± 0.24 | 1.24 to 1.37 | FLG+/− | 0.51 | 0.40 to 0.60 | <.001 |

| FLG−/− | 0.74 | 0.62 to 0.87 | <.001 | ||||

| FLG+/− | 55 | 0.80 ± 0.21 | 0.74 to 0.86 | FLG+/+ | −0.51 | −0.60- to −0.41 | <.001 |

| FLG−/− | 0.24 | 0.11 to 0.36 | <.001 | ||||

| FLG−/− | 24 | 0.57 ± 0.15 | 0.50 to 0.63 | FLG+/+ | −0.74 | −8.86 to −0.61 | <.001 |

| FLG+/− | −0.24 | −0.36 to −0.11 | <.001 |

A post hoc analysis with Tukey correction shows a statistically significant difference in mean NMF between each pairwise comparison for the 3 FLG genotype subgroups.

Tukey multiple comparisons.

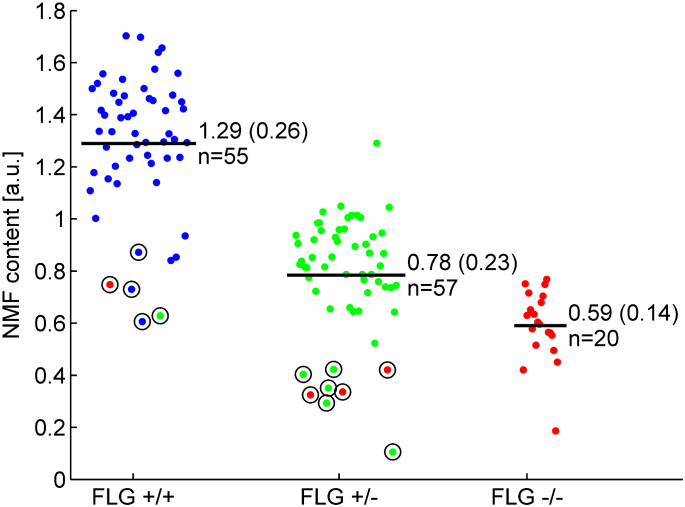

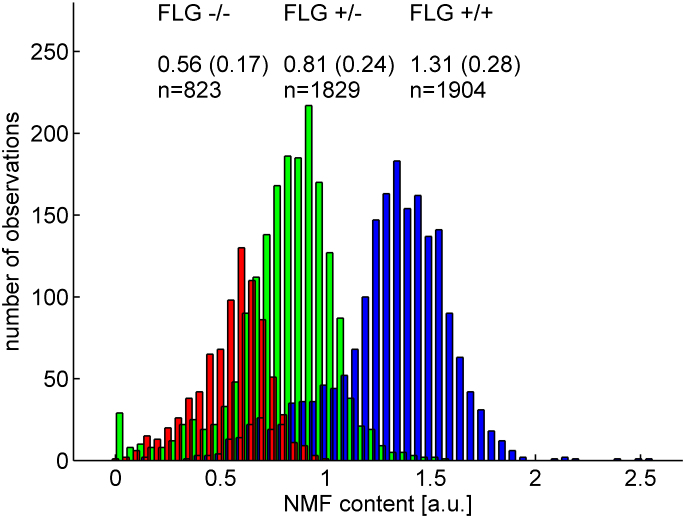

Within the FLG+/+ and FLG+/− genotype subgroups, 13 subjects had significantly outlying values with significantly lower NMF values compared with others who shared these genotypes (Fig 2). We hypothesized that these outlying values were suggestive of additional undetected FLG mutations. These 13 subjects were therefore fully sequenced for potential additional mutations. After full sequencing of these 13 subjects, 5 novel mutations (R3418X, G1138X, S1040X, 10085delC and L2933X) were detected. The entire collection was then rescreened to include 11 mutations (6 on initial screening plus these 5 additional mutations); however, no additional patients were found to harbor these novel rare mutations. NMF values by genotype after this additional screening are plotted in histogram format in Fig 3. Within FLG genotype subgroups, a range of values was seen; these values approximate to a normal distribution in each of the 3 genotype subgroups. The new mutations increased the percentage of patients with 1 or more FLG mutations in the collection to 59.8% (18.2% FLG−/−, 41.7% FLG+/−, and 40.2% FLG+/+; Table I).

Fig 2.

NMF cloud plot of values subcategorized after initial screening of 6 prevalent mutations. Circles indicate outliers who were rescreened for additional mutations. Colors indicate the final genotype after full screening. For each group, the number of patients and average NMF level (mean ± SD) are indicated in the figure. Group comparisons showing means and standard deviations by using ANOVA are presented in the text. a.u., Arbitrary units.

Fig 3.

Histogram of all nonaveraged NMF values subcategorized according to corrected mutational status. Blue bars are FLG+/+ subjects, green bars are FLG+/− subjects, and red bars are FLG−/− subjects. For each group, the number of Raman measurements and the average NMF level (mean ± SD) are indicated in the figure. FLG genotype group sizes are as follows: FLG−/−, 24; FLG+/−, 55; FLG+/+, 53. a.u., Arbitrary units.

NMF values predict FLG genotype in patients with moderate-to-severe AD

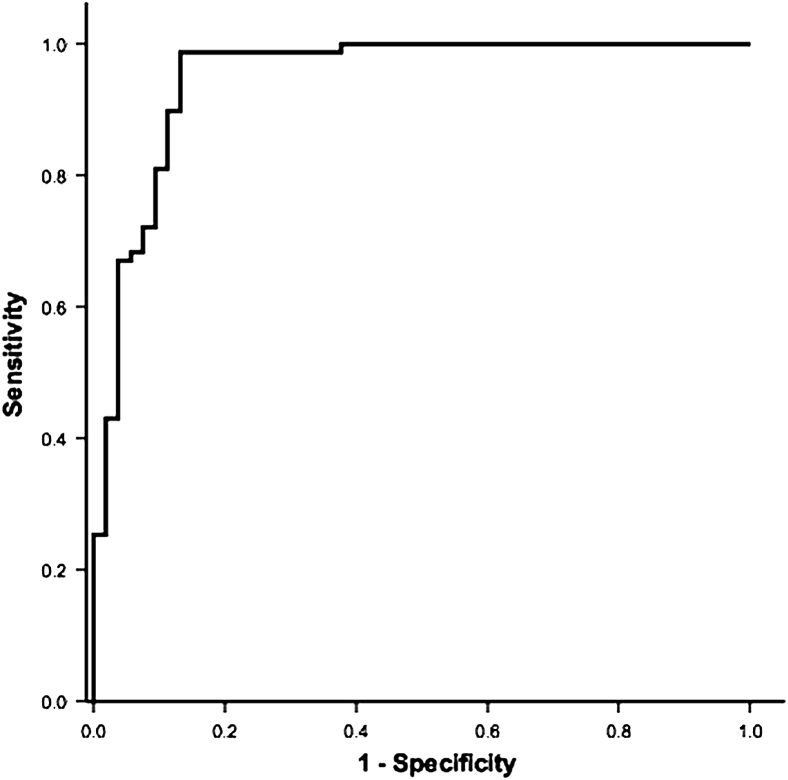

ROC curves were constructed to examine the discriminatory power of Raman-determined NMF. From a clinical decision tree, patients were initially grouped as ADFLG and ADNON-FLG (FLG+/+). The discriminatory power of Raman-determined NMF here was high, with an AUC on ROC analysis of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.91-0.99; Fig 4). The optimal cutoff value for NMF was 1.07, which would equate to a sensitivity of 98.73% and a specificity of 86.89% extrapolated from our ROC analysis. With the ADFLG group of children, NMF values also distinguished between FLG+/− and FLG−/− subjects, with an ROC AUC of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.77-0.93; see Fig E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). This sensitivity and specificity is presented to suggest the probable utility of Raman spectroscopy as a novel diagnostic technique in patients with AD and is not presented as a test for the goodness of fit of the model.

Fig 4.

ROC curve for NMF ADFLG (genotype +/− and −/−) compared with ADNON-FLG (genotype +/+). The AUC is 0.95 (95% CI, 0.91-0.99). The optimal cutoff point for mean NMF to distinguish ADFLG from ADNON-FLG was 1.07 arbitrary units.

Tyrosine peaks on Raman microspectroscopy predict FLG−/− genotype

The Raman spectra collected in the study revealed a distinct signal profile in a subset of patients subsequently identified by matching of in vitro Raman spectra of the amino acid tyrosine. Tyrosine levels 5 SDs greater than the normal tyrosine level measured in FLG+/+ subjects were identified as increased. Above this threshold, distinct tyrosine peaks could be visually identified in the corresponding Raman spectra. Tyrosine peaks were present in 19 (79%) of 24 of the patients who had 2 FLG mutations (Table I) and absent from all but 1 FLG+/+ subject, who also had an outlying low NMF level (Fig 5), suggesting an undetected genetic defect in FLG. The optimum NMF cutoff to correlate with tyrosine peaks was 0.831 (AUC, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.73-0.89), which is similar to the cutoff that distinguishes the FLG−/− from the FLG+/− populations (data not shown).

Fig 5.

Cloud plot of NMF values categorized by genotype (final genotype after full screening). Circles indicate subjects with an increased tyrosine signal (FLG+/+, n = 1; FLG+/−, n = 10; FLG−/−, n = 19). For each group, the number of patients and average NMF level (mean ± SD) are indicated in the figure. a.u., Arbitrary units.

TEWL in patients with moderate-to-severe AD does not discriminate between FLG genotype subgroups

There was no difference in mean TEWL levels among the 3 FLG genotype subgroups (Table I). TEWL did not distinguish FLG genotype status in patients with AD (TEWL AUC, 0.583; 95% CI, 0.48-0.699; ROC curve not shown).

NMF values and palmar hyperlinearity scores

There was good agreement between clinical assessment of palmar hyperlinearity and an NMF cutoff of 1.07 (κ = 0.71). Thus palmar hyperlinearity might help distinguish patients with AD into those with 1 or more FLG mutations versus those with none. Clinical assessment is not as accurate as Raman spectroscopy in distinguishing the 3 FLG genotypes. The Nottingham Eczema Severity Score did not segregate with FLG genotype in this collection (data not shown), suggesting that the spectrum of AD severity within this moderate-to-severe collection is independent of FLG genotype.

Discussion

A primary aim of this study was to investigate the utility of in vivo measurements of the SC to differentiate between FLG genotypes within patients with AD. Second, by making use of a very well-genotyped collection, we sought to determine whether FLG genotype influenced TEWL in patients with established moderate-to-severe AD. These results establish that the biochemical composition of the SC and palmar hyperlinearity associate with FLG mutation status, allowing rapid stratification of AD endotypes. Furthermore, we conclude that the degree of barrier defect, as measured by TEWL, in the clinically unaffected skin of patients with established AD is not influenced by FLG genotype.

The clinical utility of Raman-determined NMF is powerfully illustrated in the ROC curve analysis, which has an AUC of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.91-0.99) to discriminate between the ADFLG and ADNON-FLG groups. In addition, NMF can distinguish from heterozygous FLG mutations. In other words, this technique allows segregation of AD into FLG genotypes (+/+, +/−, and −/−) with such high specificity that it can accurately predict FLG genotype. Even in this relatively small patient population, mean NMF was statistically different between each of the 3 subpopulations (post hoc Tukey, Table II) Further validation of Raman-determined NMF is required in patients with well-characterized AD and healthy populations before this novel technique can be considered for clinical use.

The observed interindividual variation in NMF results within the mutation groups approximates to a normal distribution (Fig 3) that might be caused by environmental, genetic, or immunologic modifiers of FLG expression, including posttranslational processing. Homeostatic mechanisms or genetic mechanisms, such as the effects of copy number variation, small gene deletions, cytokine modulation of FLG expression, or upregulation of additional sources of NMF constituents, such as eccrine-derived lactate and glycerol, might account for differences in NMF levels within genotype groups. Modifying genes involved in filaggrin-processing pathways are likely to additionally contribute to this variation.20 The strong relationship between FLG mutation status and NMF implies that the role of other histidine-rich barrier proteins, such as the S100-fused proteins, including filaggrin-2 and hornerin, that are thought to have synergistic roles with filaggrin, including contribution to NMF levels,33-35 are unlikely to play a major role in the total NMF seen in AD patients.

The strong predictive value of a tyrosine signal in the SC of subjects with FLG mutations identifies a potential biomarker in the diagnosis of FLG-null subjects. Filaggrin lacks tyrosine; however, the linker segments and carboxyl-terminal domains of profilaggrin contain dense and highly conserved tyrosine-rich motifs.11,12,36 In normal SC only tyrosine incorporated in proteins, predominantly keratin, contributes to the overall Raman spectrum of skin; unbound tyrosine is usually not detectable. The consistent observation of the presence of tyrosine peaks in homozygous FLG mutation carriers might relate to altered biosynthetic pathways, such as limited proteolysis of profilaggrin or aberrant intermediate processing species, degraded through alternative pathways. The presence of tyrosine is independent of disease severity or mutation location.

Palmar and plantar hyperlinearity is a consistent clinical finding in the monogenic FLG disease ichthyosis vulgaris, and in keeping with a semidominant trait, intermediate hyperlinearity is thought to be associated with heterozygosity for FLG mutations; hyperlinearity has been associated as a significant finding in patients with FLG-related AD.37-40 Brown et al41 have recently shown significant association of palmar hyperlinearity with FLG-null mutations in a population-based cohort.41 Our finding that FLG status and NMF segregate with palmar hyperlinearity in patients with moderate-to-severe AD further validates the importance of this clinical sign in AD phenotypes.

Evidence from both molecular genetics and functional analyses strongly supports a skin barrier defect as a feature of both lesional and nonlesional skin in patients with AD.42-44 Increased mean baseline TEWL levels, reflecting a dysfunction of the inside-out epidermal permeability barrier in the clinically uninvolved skin of patients with AD, have been shown in many previous studies.45-47 The concept of an inherent skin barrier defect in both lesional and nonlesional skin from patients with is further supported by other methodologies, including recent data by Jakasa et al43 showing enhanced uptake of entire series of polyethylene glycols covering molecular weights in the range 150 to 590 daltons in nonlesional skin of patients with AD. Hata et al, using a photoacoustic spectroscopic system, showed enhanced penetration of both lipophilic and hydrophilic dye through clinically normal skin of patients with AD compared with that seen in control subjects.42-44

Previous investigators have reported contrasting findings on the influence of FLG mutation status on the inside-out barrier, as measured by TEWL in patients with AD; however, these studies were restricted by small sample size and possibly confounded by the technical limitations of disclosure of full FLG polymorphism status in the populations studied.10,48 A French study including a small number of FLG mutation carriers suggested that TEWL in patients with AD was not influenced by FLG status.49 Here, in our much larger collection of comprehensively genotyped patients with moderate-to-severe AD, TEWL again showed no discernable difference between FLG genotype subpopulations. These results suggest that increased TEWL in patients with moderate-to-severe AD is independent of FLG status and is a common end point in patients with moderate-to-severe AD. Thus increased TEWL might result from the systemic effects of the inflammatory process, even at nonclinically inflamed sites. Interestingly, flaky tail (ft) mice show a moderate increase in baseline TEWL, a deviation that increases dramatically after allergen priming and the subsequent secondary inflammatory response.8 In these mice, although FLG deficiency might of itself lead to an inside-out barrier defect barely measureable by increased TEWL, the subsequent marked increase in TEWL appears to be driven by the secondary immunologic response.

Within this collection, no effect was seen for FLG and disease severity or total serum IgE level; however, this case series is not the ideal collection to examine this because all cases are moderate to severe and therefore the full range of severity is not represented. Further population-based and sufficiently powered studies should clarify this potential genotype-phenotype correlation.

Within patients with AD, Raman signatures of NMF level and tyrosine predict FLG mutation status, overcoming the need for technically demanding genotyping, particularly in populations in which the FLG mutation architecture has not been comprehensively elucidated. This work additionally further informs mechanistic pathways in AD, demonstrating that TEWL in patients with moderate-to-severe AD is an outcome that is independent of FLG mutation status and pointing to a complex systemic interplay of environmental, immunologic, and functional pathways in the genesis of epithelial barrier disruption in patients with AD.

Key messages.

-

•

Raman spectroscopy, specifically NMF analysis, permits rapid and accurate stratification of FLG-associated versus non–FLG-associated AD and might be useful as a predictive test for FLG mutations.

-

•

There is good agreement between FLG mutation status, NMF, and clinical palmar hyperlinearity scoring in patients with moderate-to-severe AD. Palmar hyperlinearity might help to define a clinical and genetic phenotype of AD.

-

•

Within patients with moderate-to-severe AD, TEWL levels do not segregate with FLG genotype, suggesting that FLG mutations are neither necessary nor sufficient to fully explain this inside-out barrier defect in established AD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families for their involvement in this study.

Footnotes

Filaggrin research in the McLean laboratory is funded by grants from the British Skin Foundation, Medical Research Council, and donations from families affected by atopic dermatitis in the Tayside Region of Scotland. G.M.O'R. and A.D.I. are supported by the Children's Medical and Research Foundation, Dublin, Ireland.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: W. H. I. McLean receives research support from the British Skin Foundation. A. D. Irvine receives research support from the Children's Medical and Research Foundation. The rest of the authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Fig E1.

ROC curve for NMF values to distinguish FLG+/− subjects from FLG−/− subjects in the ADFLG group. AUC is 0.85 (95% CI, 0.76-0.93), with a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 66.77% at a cutoff of 0.767 arbitrary units.

References

- 1.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483–1494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung D.Y., Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2003;361:151–160. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandilands A., O'Regan G.M., Liao H., Zhao Y., Terron-Kwiatkowski A., Watson R.M. Prevalent and rare mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris and predispose individuals to atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1770–1775. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker J.N., Palmer C.N., Zhao Y., Liao H., Hull P.R., Lee S.P. Null mutations in the filaggrin gene (FLG) determine major susceptibility to early-onset atopic dermatitis that persists into adulthood. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:564–567. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baurecht H., Irvine A.D., Novak N., Illig T., Buhler B., Ring J. Toward a major risk factor for atopic eczema: meta-analysis of filaggrin polymorphism data. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1406–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weidinger S., O'Sullivan M., Illig T., Baurecht H., Depner M., Rodriguez E. Filaggrin mutations, atopic eczema, hay fever, and asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1203–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.014. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias P.M. Skin barrier function. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8:299–305. doi: 10.1007/s11882-008-0048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallon P.G., Sasaki T., Sandilands A., Campbell L.E., Saunders S.P., Mangan N.E. A homozygous frameshift mutation in the mouse Flg gene facilitates enhanced percutaneous allergen priming. Nat Genet. 2009;41:602–608. doi: 10.1038/ng.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginger R.S., Blachford S., Rowland J., Rowson M., Harding C.R. Filaggrin repeat number polymorphism is associated with a dry skin phenotype. Arch Dermatol Res. 2005;297:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s00403-005-0590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kezic S., Kemperman P.M., Koster E.S., de Jongh C.M., Thio H.B., Campbell L.E. Loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene lead to reduced level of natural moisturizing factor in the stratum corneum. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2117–2119. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gan S.Q., McBride O.W., Idler W.W., Markova N., Steinert P.M. Organization, structure, and polymorphisms of the human profilaggrin gene. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9432–9440. doi: 10.1021/bi00492a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Presland R.B., Haydock P.V., Fleckman P., Nirunsuksiri W., Dale B.A. Characterization of the human epidermal profilaggrin gene. Genomic organization and identification of an S-100-like calcium binding domain at the amino terminus. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23772–23781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segre J. Complex redundancy to build a simple epidermal permeability barrier. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:776–782. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalinin A.E., Kajava A.V., Steinert P.M. Epithelial barrier function: assembly and structural features of the cornified cell envelope. Bioessays. 2002;24:789–800. doi: 10.1002/bies.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candi E., Schmidt R., Melino G. The cornified envelope: a model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:328–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rawlings A.V., Scott I.R., Harding C.R., Bowser P.A. Stratum corneum moisturization at the molecular level. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:731–741. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12398620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott I.R., Harding C.R. Filaggrin breakdown to water binding compounds during development of the rat stratum corneum is controlled by the water activity of the environment. Dev Biol. 1986;115:84–92. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawlings A.V., Matts P.J. Stratum corneum moisturization at the molecular level: an update in relation to the dry skin cycle. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1099–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2005.23726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krien P.M., Kermici M. Evidence for the existence of a self-regulated enzymatic process within the human stratum corneum—an unexpected role for urocanic acid. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:414–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandilands A., Sutherland C., Irvine A.D., McLean W.H. Filaggrin in the frontline: role in skin barrier function and disease. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1285–1294. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouwstra J.A., Groenink H.W., Kempenaar J.A., Romeijn S.G., Ponec M. Water distribution and natural moisturizer factor content in human skin equivalents are regulated by environmental relative humidity. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:378–388. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa N., Sakai S., Matsumoto M., Yamada K., Nagano M., Yuki T. Relationship between NMF (lactate and potassium) content and the physical properties of the stratum corneum in healthy subjects. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howell M.D., Kim B.E., Gao P., Grant A.V., Boguniewicz M., Debenedetto A. Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKinley-Grant L.J., Idler W.W., Bernstein I.A., Parry D.A., Cannizzaro L., Croce C.M. Characterization of a cDNA clone encoding human filaggrin and localization of the gene to chromosome region 1q21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4848–4852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong K.K., deLeeuw R.J., Dosanjh N.S., Kimm L.R., Cheng Z., Horsman D.E. A comprehensive analysis of common copy-number variations in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:91–104. doi: 10.1086/510560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams H.C., Burney P.G., Hay R.J., Archer C.B., Shipley M.J., Hunter J.J. The U.K. Working Party's Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:383–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emerson R.M., Charman C.R., Williams H.C. The Nottingham Eczema Severity Score: preliminary refinement of the Rajka and Langeland grading. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:288–297. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandilands A., Smith F.J., Irvine A.D., McLean W.H. Filaggrin's fuller figure: a glimpse into the genetic architecture of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1282–1284. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandilands A., Terron-Kwiatkowski A., Hull P.R., O'Regan G.M., Clayton T.H., Watson R.M. Comprehensive analysis of the gene encoding filaggrin uncovers prevalent and rare mutations in ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic eczema. Nat Genet. 2007;39:650–654. doi: 10.1038/ng2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caspers P.J., Lucassen G.W., Carter E.A., Bruining H.A., Puppels G.J. In vivo confocal Raman microspectroscopy of the skin: noninvasive determination of molecular concentration profiles. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:434–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caspers P.J., Lucassen G.W., Puppels G.J. Combined in vivo confocal Raman spectroscopy and confocal microscopy of human skin. Biophys J. 2003;85:572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74501-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daly L.E., Bourke G. 5th ed. Blackwell Scientific Press; Oxford: 2000. Interpretation and uses of medical statistics. p. 381-421. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esparza-Gordillo J., Weidinger S., Folster-Holst R., Bauerfeind A., Ruschendorf F., Patone G. A common variant on chromosome 11q13 is associated with atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:596–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Z., Hansmann B., Meyer-Hoffert U., Glaser R., Schroder J.M. Molecular identification and expression analysis of filaggrin-2, a member of the S100 fused-type protein family. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toulza E., Mattiuzzo N.R., Galliano M.F., Jonca N., Dossat C., Jacob D. Large-scale identification of human genes implicated in epidermal barrier function. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R107. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resing K.A., Walsh K.A., Haugen-Scofield J., Dale B.A. Identification of proteolytic cleavage sites in the conversion of profilaggrin to filaggrin in mammalian epidermis. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1837–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith F.J., Irvine A.D., Terron-Kwiatkowski A., Sandilands A., Campbell L.E., Zhao Y. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris. Nat Genet. 2006;38:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ng1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novak N., Baurecht H., Schafer T., Rodriguez E., Wagenpfeil S., Klopp N. Loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene and allergic contact sensitization to nickel. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1430–1435. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weidinger S., Illig T., Baurecht H., Irvine A.D., Rodriguez E., Diaz-Lacava A. Loss-of-function variations within the filaggrin gene predispose for atopic dermatitis with allergic sensitizations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sergeant A., Campbell L.E., Hull P.R., Porter M., Palmer C.N., Smith F.J. Heterozygous null alleles in filaggrin contribute to clinical dry skin in young adults and the elderly. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1042–1045. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown S.J., Relton C.L., Liao H., Zhao Y., Sandilands A., McLean W.H. Filaggrin haploinsufficiency is highly penetrant and is associated with increased severity of eczema: further delineation of the skin phenotype in a prospective epidemiological study of 792 school children. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:884–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jakasa I., Verberk M.M., Bunge A.L., Kruse J., Kezic S. Increased permeability for polyethylene glycols through skin compromised by sodium lauryl sulphate. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:801–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jakasa I., Verberk M.M., Esposito M., Bos J.D., Kezic S. Altered penetration of polyethylene glycols into uninvolved skin of atopic dermatitis patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:129–134. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hata M., Tokura Y., Takigawa M., Sato M., Shioya Y., Fujikura Y. Assessment of epidermal barrier function by photoacoustic spectrometry in relation to its importance in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Lab Invest. 2002;82:1451–1461. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000036874.83540.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seidenari S., Giusti G. Objective assessment of the skin of children affected by atopic dermatitis: a study of pH, capacitance and TEWL in eczematous and clinically uninvolved skin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:429–433. doi: 10.2340/0001555575429433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elias P.M., Hatano Y., Williams M.L. Basis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1337–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eberlein-Konig B., Schafer T., Huss-Marp J., Darsow U., Mohrenschlager M., Herbert O. Skin surface pH, stratum corneum hydration, trans-epidermal water loss and skin roughness related to atopic eczema and skin dryness in a population of primary school children. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:188–191. doi: 10.1080/000155500750042943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nemoto-Hasebe I., Akiyama M., Nomura T., Sandilands A., McLean W.H., Shimizu H. Clinical severity correlates with impaired barrier in filaggrin-related eczema. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:682–689. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hubiche T., Ged C., Benard A., Leaute-Labreze C., McElreavey K., de Verneuil H. Analysis of SPINK 5, KLK 7 and FLG genotypes in a French atopic dermatitis cohort. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:499–505. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]