Abstract

We investigated the ionic mechanisms that allow dynamic regulation of action potential (AP) amplitude as a means of regulating energetic costs of AP signaling. Weakly electric fish generate an electric organ discharge (EOD) by summing the APs of their electric organ cells (electrocytes). Some electric fish increase AP amplitude during active periods or social interactions and decrease AP amplitude when inactive, regulated by melanocortin peptide hormones. This modulates signal amplitude and conserves energy. The gymnotiform Eigenmannia virescens generates EODs at frequencies that can exceed 500 Hz, which is energetically challenging. We examined how E. virescens meets that challenge. E. virescens electrocytes exhibit a voltage-gated Na+ current (INa) with extremely rapid recovery from inactivation (τrecov = 0.3 ms) allowing complete recovery of Na+ current between APs even in fish with the highest EOD frequencies. Electrocytes also possess an inwardly rectifying K+ current and a Na+-activated K+ current (IKNa), the latter not yet identified in any gymnotiform species. In vitro application of melanocortins increases electrocyte AP amplitude and the magnitudes of all three currents, but increased IKNa is a function of enhanced Na+ influx. Numerical simulations suggest that changing INa magnitude produces corresponding changes in AP amplitude and that KNa channels increase AP energy efficiency (10–30% less Na+ influx/AP) over model cells with only voltage-gated K+ channels. These findings suggest the possibility that E. virescens reduces the energetic demands of high-frequency APs through rapidly recovering Na+ channels and the novel use of KNa channels to maximize AP amplitude at a given Na+ conductance.

Keywords: action potential energy efficiency, sodium-activated potassium channels, ion channel regulation, electric organ discharge, weakly electric fish

energetic demands of action potential (AP) generation are a major cost of electrical signaling by excitable cells in the central nervous system and periphery (Alle et al. 2009; Attwell and Laughlin 2001; Carter and Bean 2009; Hallermann et al. 2012; Sengupta et al. 2010). Energy consumption by AP generation is particularly acute in the electric organ (EO) of weakly electric fish. These nocturnally active fish generate and sense electric fields, known as electric organ discharges (EODs), in the surrounding water to analyze nearby objects and communicate with conspecifics. EODs are generated by the synchronized APs of electrogenic cells (electrocytes) in the EO. Electrocyte ionic currents are often several microamperes (Ferrari and Zakon 1993), many orders of magnitude larger than currents in central neurons, creating significant energetic costs of AP generation. Some species dynamically regulate AP amplitude to control energy demands of AP generation (Markham et al. 2009; Salazar and Stoddard 2008).

One class of South American electric fish, wave-type fish, generate a quasi-sinusoidal waveform produced by EODs emitted at highly regular rates with interpulse intervals roughly equal to the EOD duration. Discharge frequency is highly stable throughout the life span, creating high energetic demands that cannot be reduced by slowing AP frequency in the EO (Crampton 1998). The wave-type fish Sternopygus macrurus (EOD frequencies 50–200 Hz) manages EOD energetic costs by reducing EOD amplitude during times of inactivity and increasing EOD amplitude only during active periods and social interaction. These EOD amplitude modulations are produced by rapid changes in AP amplitude controlled by circulating melanocortin hormones that upregulate Na+ channel trafficking into the electrocyte membrane (Markham et al. 2009).

Species that discharge at much higher frequencies likely incur proportionately higher energetic costs. In the high-frequency wave-type fish Eigenmannia virescens (EOD frequency 200–600 Hz), EOD amplitude appears to be sensitive to energetic constraints (Reardon et al. 2011), and this species exhibits large day-night changes in EOD amplitude, potentially a mechanism of energetic regulation (Hagedorn and Heiligenberg 1985; P. Stoddard, unpublished observation).

Here we investigated the ionic mechanisms that support high-frequency EODs and EOD amplitude modulation in E. virescens. The ionic currents of these electrocytes have not been characterized, nor have the ionic mechanisms of EOD amplitude modulation been determined. We found that melanocortin peptides regulate AP amplitude by rapidly enhancing electrocyte voltage-gated Na+ current (INa) as found in other species. Additionally, we identified a novel adaptation that further increases energy efficiency of these high-frequency APs. The dominant repolarizing current in E. virescens electrocytes is a Na+-activated K+ current (IKNa) not found in the EO of any other gymnotiform species to date. Numerical simulations suggest that these KNa channels prevent energetically wasteful overlap of inward Na+ and outward K+ currents during the AP, thereby increasing AP energy efficiency compared with model cells with Na+-insensitive voltage-gated K+ channels having kinetics matching KNa. Thus E. virescens reduces the energetic demands of high-frequency APs through dynamic modulation of AP amplitude and the novel use of KNa channels to maximize AP amplitude across a range of Na+ conductance (GNa) magnitudes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Fish were wild-caught male and female E. virescens (glass knife fish) from tropical South America, obtained from Segrest Farms (Gibsonton, FL) and ranging in size from 11 to 18 cm. Fish were housed in groups of 10–20 in 300-liter tanks at 28 ± 1°C with water conductivity of 400–600 μS/cm. The EOD of E. virescens is a quasi-sinusoidal wave with a frequency of 200–600 Hz (Fig. 1A). Each pulse of the wave is a single EOD, and these occur at regular intervals under the control of a medullary pacemaker nucleus. All methods were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Texas and complied with the guidelines given in the Public Health Service Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Fig. 1.

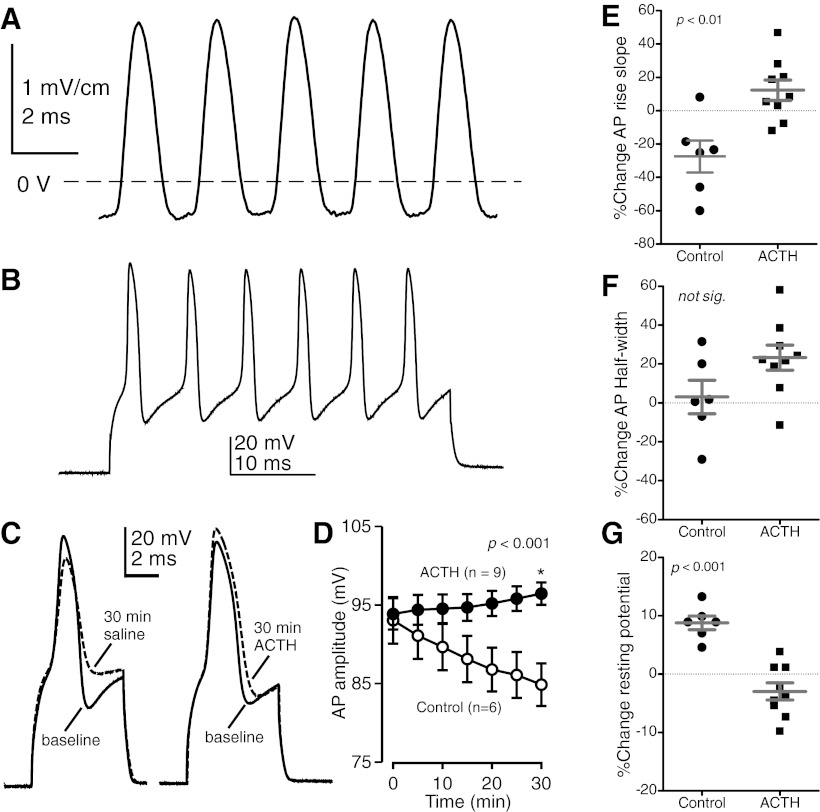

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) increases electrocyte action potential (AP) amplitude. A: electric organ discharge (EOD) waveform of a representative fish recorded in vivo. B: representative train of APs elicited by a 40-ms depolarizing current step (7,000 nA). C: electrocyte APs recorded at baseline and then after 30-min exposure to ACTH or control conditions. D: changes in AP amplitude during 30-min exposure to ACTH or normal saline (control cells). Treatment with ACTH increased the amplitude of electrocyte APs compared with controls after 30 min (n = 15; t = 3.971, df = 13, P < 0.001). E–G: % change from baseline in AP parameters after 30-min exposure to ACTH or 30-min saline control. Closed circles and squares are individual data points; horizontal bars and error bars represent means and SE, respectively. AP rise slope (E) increased after ACTH treatment relative to controls (n = 15; t = 3.694, df = 13, P < 0.01). AP half-width (F) did not increase in ACTH-treated cells (n = 15; t = 1.924, df = 13, P > 0.05). Resting membrane potential (G) depolarized slightly in control conditions relative to ACTH-treated cells (n = 15; t = 5.712, df = 13, P < 0.001).

Solutions and reagents.

We obtained all reagents from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) except for tetrodotoxin (TTX), which was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The normal saline for in vitro physiology contained (in mM) 114 NaCl, 2 KCl, 4 CaCl2·2H2O, 2 MgCl2·6H2O, 2 HEPES, and 6 glucose; pH to 7.2 with NaOH. For experimental conditions that required reductions to external Na+ concentrations, we substituted some portion of the external NaCl with equimolar N-methyl-d-glucamine. In experiments where Li+ was substituted for external Na+, we substituted 114 mM LiCl for the external NaCl.

Electrophysiology.

Procedures for current clamp and two-electrode voltage clamp of electrocytes have been described and validated previously (Ferrari and Zakon 1993; McAnelly et al. 2003; McAnelly and Zakon 2000). We harvested a 1.5- to 2-cm section of the tail, removed the overlying skin, and pinned the exposed EO in a Sylgard recording dish containing normal saline with 1 μM pancuronium bromide added to prevent spontaneous contractions from any tail muscles that might be present in the section. In all experiments, test compounds were dissolved in the recording saline and bath-perfused into the recording chamber. Temperature of the preparation was stable at room temperature (24 ± 1°C).

Electrophysiological recordings were made with an Axoclamp 900 amplifier controlled by a Digidata 1440 interface and pCLAMP 10 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Sampling rate was at least 50 kHz for all experiments. A two-electrode configuration was used in both current-clamp and voltage-clamp experiments. In both current-clamp and voltage-clamp experiments, we recorded membrane potential with a unity-gain headstage (Molecular Devices HS9A x1) and injected current with a X10 headstage (Molecular Devices HS 9A x10) to allow delivery of currents up to 10 μA. Microelectrodes were pulled from thin-wall borosilicate glass to resistances of 0.9–1.2 MΩ when filled with 3 M KCl. The bath was grounded via a chlorided silver wire inserted into a 3 M KCl agar bridge.

E. virescens electrocytes have morphology similar to the extensively studied electrocytes of S. macrurus. Electrocytes are cylindrical cells ∼800 μm long and 300 μm in diameter, innervated on the posterior face of the cell. Only the posterior face is electrically excitable, while the anterior portion of the cell exhibits only linear leak. Electrodes penetrated the most posterior portion of the cell, the region of the electrocyte's voltage-gated ion channels. We used amplifier gains of 10,000–15,000 V/V and placed a grounded shield between the electrodes to prevent capacitative coupling.

For current-clamp experiments, we elicited APs by delivering 6-ms depolarizing current steps and increasing current intensity until the step reliably elicited APs. Threshold currents were quite large, usually in the range of 3,000–7,500 nA. Input resistance was monitored via two 10-ms current steps of +200 nA and −200 nA delivered before the suprathreshold current step. Baseline recordings were made in normal saline before superfusion with additional normal saline as a control or with a test solution containing 100 nM of the melanocortin hormone adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) dissolved in normal saline. We then elicited APs again at 5-min intervals after solution exchange and ended the experiment after 30 min in experimental or control conditions.

In voltage-clamp experiments, we held the cells at resting potential (−85 to −95 mV) and first stepped the membrane potential to −120 mV to relieve inactivation of all Na+ channels before all subsequent voltage steps. To record basic current-voltage (I-V) activation characteristics, we then delivered 25-ms voltage steps from −110 to + 60 mV in 5-mV increments. In some cells, we reduced the number of depolarizing steps to prevent exceptionally large currents from saturating the amplifier. Baseline voltage-clamp recordings were made in normal saline, and then recordings were repeated at 5-min intervals for 30 min in normal saline control conditions or in saline with 100 nM ACTH.

In addition to the activation protocols, we recorded INa inactivation characteristics with a paired-pulse protocol of 25-ms steps from −110 to 0 mV in 5-mV increments followed by a 10-ms step to 0 mV. Recovery from inactivation for INa was assessed with pairs of voltage steps from −120 mV to 0 mV separated by recovery intervals that increased in 0.25-ms increments from 0.25 ms to 2.5 ms.

All electrophysiology data were analyzed with Clampfit 10 (Molecular Devices). AP amplitude was measured from resting potential to the membrane potential at AP peak. Duration of the AP was measured as the spike width at half-amplitude, and the AP rise slope was measured as the rising slope from 50% to 90% of the AP amplitude. Input resistance was measured by taking the inverse of the slope from a straight-line fit to the I-V plots for the 200-nA hyper- and depolarizing current steps.

During voltage-clamp experiments we identified three voltage-dependent ion currents, an inwardly rectifying K+ current (IKIR), a voltage-gated Na+ current (INa), and a Na+-activated K+ current (IKNa). We quantified IKIR magnitude as the steady-state inward current at −120 mV, INa magnitude as the peak inward current at −20 mV, and IKNa magnitude as the steady-state outward current at −20 mV. We estimated inactivation τ for INa by fitting an exponential decay function to the current trace from the first inflection point after the peak inward current curve to the point at which the current declined to 10% of its peak value. Inactivation of INa was adequately fit with a standard single-exponential decay function:

Numerical simulations.

Simulations were carried out with a model similar to that described previously to evaluate the effects of splice isoforms of Slack channels on the firing properties of neurons (Brown et al. 2008). Responses were simulated by integration of the equation

where INa represents Na+ current, IKNa and IR represent Na+-activated and inward rectifier K+ currents, respectively, Ileak is the leak current, and Iext(t) represents externally applied current pulses. The capacitance C was 50.0 nF, a value representative of electrocyte membrane capacitances measured electrophysiologically and estimated from membrane surface area. Electrocytes are cylindrical cells with voltage-gated ion channels localized to the posterior region of the cell, with the anterior region of the cell contributing only linear leak. Our model cell approximated the electrocyte as a single-compartment sphere with voltage-gated conductances and linear leak in parallel. The spatial distribution of conductances was therefore uniform in the simulated cell, but the total active and passive conductances were fixed to those empirically observed in electrocytes. Thus estimates of total ionic flux in our simulations are representative of physiological conditions.

The equation for INa was split into transient INaT and persistent INaP components, where

and where 0 < γ <1.

Equations for IKNa, IR, and Ileak were as follows:

The evolution of the variables m, h, and n was given by equations of the form

where

and j = m, h, n.

gNa was varied from 400 to 1,200 μS, and γ, the proportion of total Na+ current that is a persistent current that does not inactivate, was set at 0.1. Kinetic parameters for the evolution of the variables m and h were kαm = 7.6 ms−1, ηαm = 0.0037 mV−1, kβm = 0.6894 ms−1, ηβm = −0.0763 mV−1 and kαh = 0.00165 ms−1, ηαh = −0.1656 mV−1, kβh = 0.993 ms−1, and ηβh = −0.0056 mV−1. For the KNa current, gKNa = 2,000 μS, with kαn = 1.209 ms−1, ηαn = 0.00948 mV−1, kβn = 0.4448 ms−1, and ηβn = −0.01552 mV−1. For the inward rectifier current IR, gR = 300 μS and ηR = 0.22 mV−1. For the leak current Ileak, gleak = 0.76 μS.

The gating variable s in the equations for IKNa represents the proportion of Slack channels activated by intracellular Na+ concentration. Changes in intracellular Na+ at the cytoplasmic face of the KNa channels were modeled by the equation

where the kinetic constant a governs the access of the KNa channels to Na+ entering though the persistent voltage-dependent Na+ channels (Hage and Salkoff 2012), a′ represents a Na+ leak, and b determines the rate of pumping of Na+ out of the cell. In the model cell, a = 2.5, a′ = 12.5 mM·ms−1, and b = 0.5 ms−1. The variable s evolves according to the equation

with kf = 10.0 mM−1·ms−1 and kb = 2.0 ms−1.

To model delayed-rectifier currents (IKV; see Fig. 8B) that have the kinetic properties of Slack currents but are unaffected by changes in intracellular Na+, the value of s was simply fixed at 1. To model the effects of the Kv3.1 channel on repolarization, the equation for IKNa was replaced by the equation

where the variables n and p were integrated as described above for the generic gating variable j, but with the kinetic parameters kαn = 0.2719 ms−1, ηαn = 0.04 mV−1, kβn = 0.1974 ms−1, ηβn = 0 mV−1, kαp = 0.00713 ms−1, ηαp = −0.1942 mV−1, kβp = 0.0935 ms−1, and ηβp = 0.0058 mV−1. These parameters are based on fits to Kv3.1 currents measured in transfected cells and auditory brain stem neurons (Macica et al. 2003). For the simulations in Fig. 8, gKv3.1 = 4,000 μS.

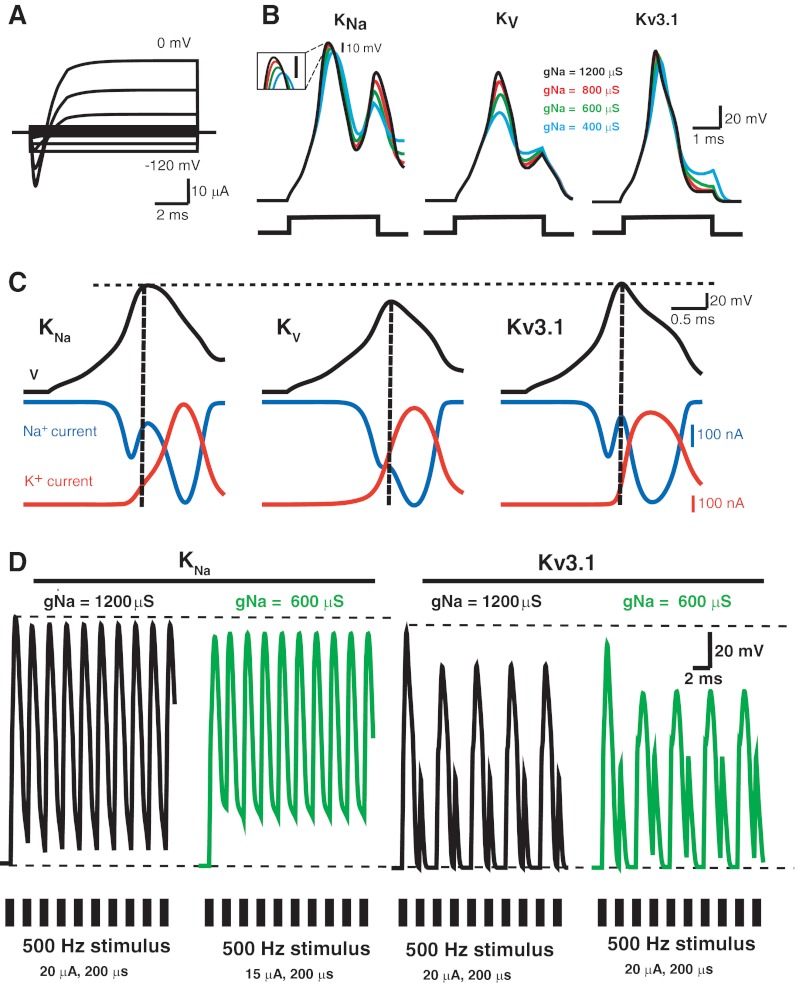

Fig. 8.

Numerical simulations of the effects of KNa currents on firing properties of a model electrocyte. A: simulated whole cell currents evoked by depolarizing steps from holding potential of −95 mV to potentials ranging from −120 mV to 0 mV in 10-mV increments. B: simulated APs elicited by depolarizing current steps (3 ms, 4 μA) in a model electrocyte with a Na+-activated K+ current (KNa, left), a model cell where the outward K+ conductance is insensitive to intracellular Na+ (Kv, center), or one in which the K+ current has the properties of Kv3.1 (right). Superimposed traces show simulated APs in cells with Na+ conductance magnitudes ranging from 400 μS to 1,200 μS. Inset for KNa simulations is expanded view of AP peaks; scale bar, 10 mV. C: time course of membrane potential (black), Na+ current (blue), and K+ current (red) during single action potentials in cells with KNa, KV, or Kv3.1 as in B with a Na+ conductance magnitude of 1,200 μS. Vertical dotted line shows the time of the peak of APs. D: responses of model electrocytes with KNa current (left) or Kv3.1 current (right) and different voltage-gated Na+ conductance magnitudes to a 500-Hz stimulus train (20 μA, 200-μs pulses).

In simulations of current-clamp responses, stimuli Iext(t) were presented either as a single step current (4,000 nA, 3 ms; see Fig. 8, B and C) or as a train of brief repetitive current pulses (0.2 ms, 20,000 nA, 500 Hz; see Fig. 8D). Differential equations were encoded, compiled, and integrated with QB64 software, using Euler's method with time steps of 7.8–31.2 × 10−11 s.

Molecular biology.

We extracted RNA from homogenized tissue samples of EO and skeletal (hypaxial) muscle of E. virescens with the guanidinium thiocyanate method. RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with primers specific for the Na+-activated K+ channel SLACK (Joiner et al. 1998; Yuan et al. 2003) and GAPDH as a positive control. Simultaneous PCR reactions for both products were performed for both skeletal muscle and EO. The use of the same primer sets for both skeletal muscle and EO and the amplification of GAPDH in both tissues served as an internal control for the quality of RNA and the effectiveness of the primers. Primer and amplified product sequences are available on request.

Data analysis.

All statistical comparisons of means between groups were conducted with unpaired t-tests. Goodness of fit for linear regressions was measured by r2, and tests for nonzero slope of linear regressions were conducted with appropriate F-tests. We used repeated-measures ANOVA to evaluate differences between groups when repeated observations were performed on each group. All statistical analyses were performed with Prism 5 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) or MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Group data are reported as means ± SE.

RESULTS

ACTH modulates AP amplitude.

Electrocytes normally generated a single AP in response to depolarizing current steps. During the first few minutes of baseline recordings, sustained depolarizing current steps elicited trains of APs in many cells (Fig. 1B). This pattern disappears within minutes in control conditions, perhaps because of rundown in excitatory ion currents. We found that electrocyte AP amplitude increased within 30 min after bath application of ACTH, whereas in control cells these parameters decreased during 30 min of continued exposure to normal saline (Fig. 1, C and D). In control cells AP amplitude decreased after 30 min by 8.2 ± 1.2 mV, while AP amplitude increased by 2.6 ± 1.3 mV in ACTH-treated cells, an increase of >10 mV relative to controls. The rundown of AP amplitude in control cells was pronounced, with AP amplitude declining in all control cells at a linear rate of 0.268 ± 0.015 mV/min. This rundown is likely due to the fact that during in vitro experiments electrocytes are removed from sources of endogenous circulating melanocortin hormones. The rundown of AP amplitude in the present study is consistent with observations from electrocytes of other electric fish species (Markham and Stoddard 2005; McAnelly et al. 2003). We also found that ACTH increased AP rise slope but not AP half-width and that resting membrane potential depolarized slightly in control cells but maintained baseline levels in ACTH-treated cells (Fig. 1, E–G). Input resistance did not change in either condition (data not shown).

Eigenmannia electrocytes have three ionic currents.

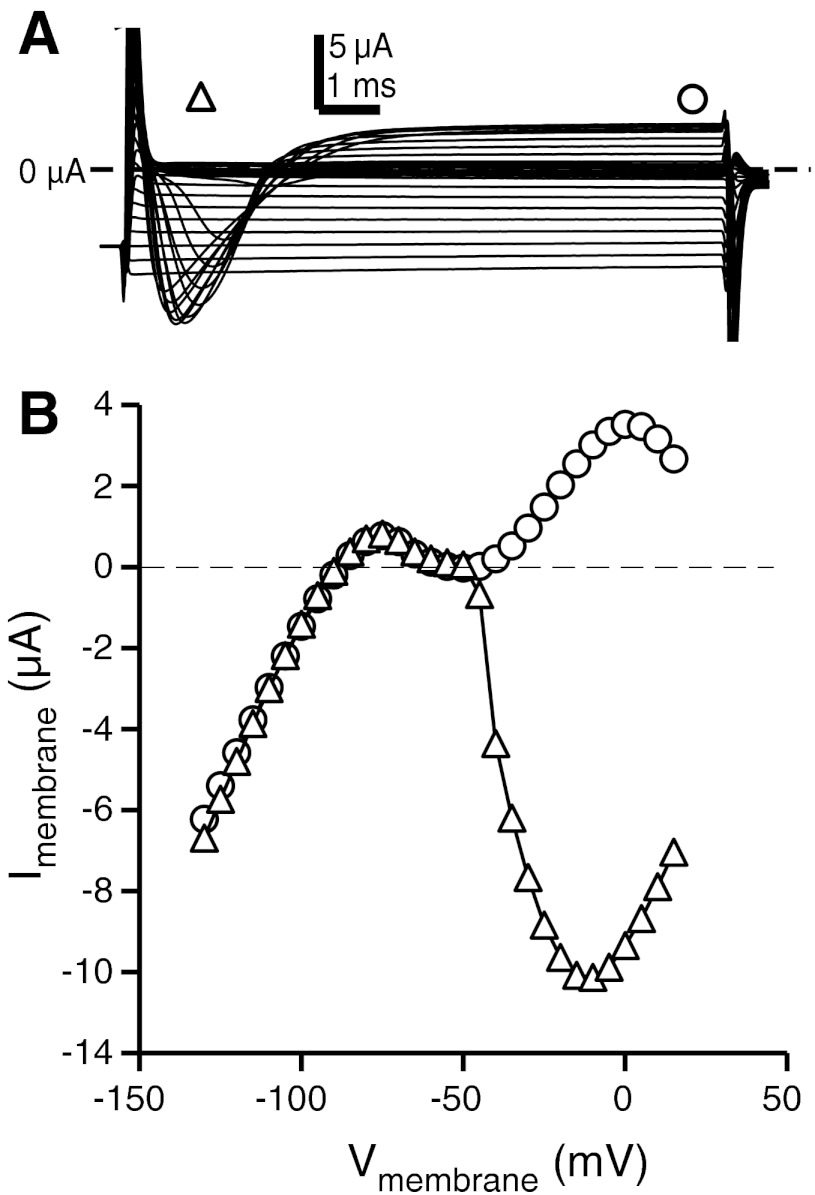

To investigate the ionic mechanisms underlying increases in AP amplitude, we first characterized the ionic currents present in electrocytes. Under two-electrode voltage clamp in normal saline, whole cell currents show three voltage-dependent components, an inwardly rectifying K+ current, an inactivating inward Na+ current, and an outward noninactivating K+ current evident at depolarized membrane potentials (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Whole cell ionic currents show strong inward rectification, a transient inactivating inward current, and a sustained outward current. A: representative leak-subtracted voltage-clamp traces from a single electrocyte in response to voltage steps from −130 to +15 mV in 5-mV increments. Open triangle and circle indicate where current magnitudes were measured for the current-voltage (I-V) plots shown in B. B: I-V plots for minimum current measured during the transient inward phase (triangles) and current measured at steady-state (circles).

Sodium currents (INa) were isolated by adding 1 mM BaCl2 and 20 mM TEA to the bath saline. These conditions eliminated all outward currents and inward rectification. Steady-state currents from −55 to −45 mV matched well before and after addition of BaCl and TEA and showed a linear I-V slope. We therefore used the I-V slope at these membrane potentials to calculate the linear leak for each cell and subtracted this linear leak from all raw current traces for the cell prior to further analysis.

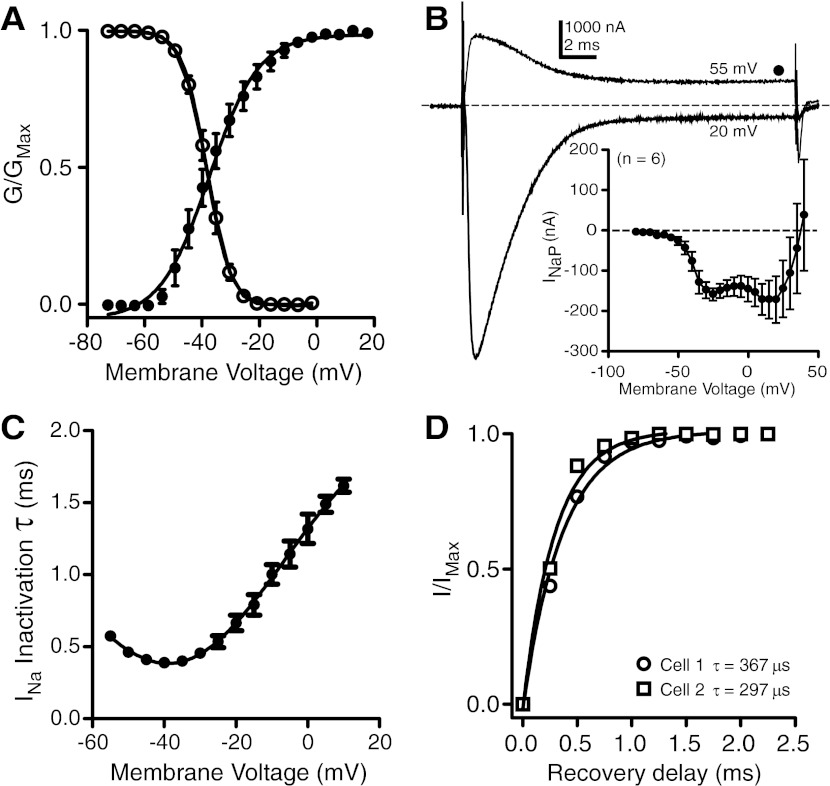

In the presence of 1 mM Ba2+ and 20 mM TEA to block all K+ currents, INa in Eigenmannia electrocytes shows voltage dependence of activation and inactivation typical of voltage-gated Na+ currents (Fig. 3A). We also found a small persistent component of INa (INaP) after preliminary computational simulations suggested its presence (Fig. 3B). Using a p/8 leak subtraction protocol and a steady-state amplifier gain of 106 V/V, we observed in leak-corrected steady-state recordings currents that are inward for membrane potentials from −40 to +40 mV and reverse near +45 mV, consistent with the reversal potentials observed for the transient INa.

Fig. 3.

Activation, inactivation, and recovery characteristics of INa: all recordings in the presence of 1 mM Ba2+ and 20 mM TEA to block all K+ currents. A: voltage dependence of INa activation (filled circles, n = 5) and INa inactivation (open circles, n = 5); solid lines are Boltzmann sigmoidal fits. G, conductance. B: persistent component of INa (INaP). Representative currents recorded during voltage steps to 20 mV and 55 mV show persistent current at steady state. Inset: steady-state I-V plots show a small inward current that reverses near +45 mV. C: voltage dependence of INa inactivation time constant (τ, n = 5). Inactivation time constant was estimated by fitting a single exponential to the inactivation phase of INa at membrane potentials from −55 to +15 mV. D: INa recovery from inactivation in 2 cells: fractional recovery of INa relative to maximum current for 2 cells across recovery delays from 0 to 2.25 ms in 0.25-ms increments. Solid lines are single-exponential fits.

The τ-V relationship for the rate of INa inactivation (Fig. 3C) is atypical for most Na+ currents, which usually inactivate with shorter time constants as membrane depolarization increases. Our data show that INa inactivates faster as membrane potential becomes more depolarized until reaching a minimum at −40 mV, after which inactivation becomes progressively slower with increased depolarization. This outcome, although unusual, is consistent with INa inactivation properties observed in related species of electric fish (Ferrari and Zakon 1993) and the electric eel (Shenkel and Sigworth 1991).

In almost all recordings, INa recovery from inactivation occurred so quickly that recovery was nearly complete during the large capacitive transients in the current records and before the voltage clamp could settle on the command voltage (∼400 μs). In two small electrocytes we achieved a clamp speed sufficient to resolve the time course of recovery from inactivation (Fig. 3D) by using a reduced-Na+ external saline and the amplifier's maximum gain (50,000 V/V). Recovery data for both cells were well fit with single exponentials and time constants of 367 μs and 297 μs.

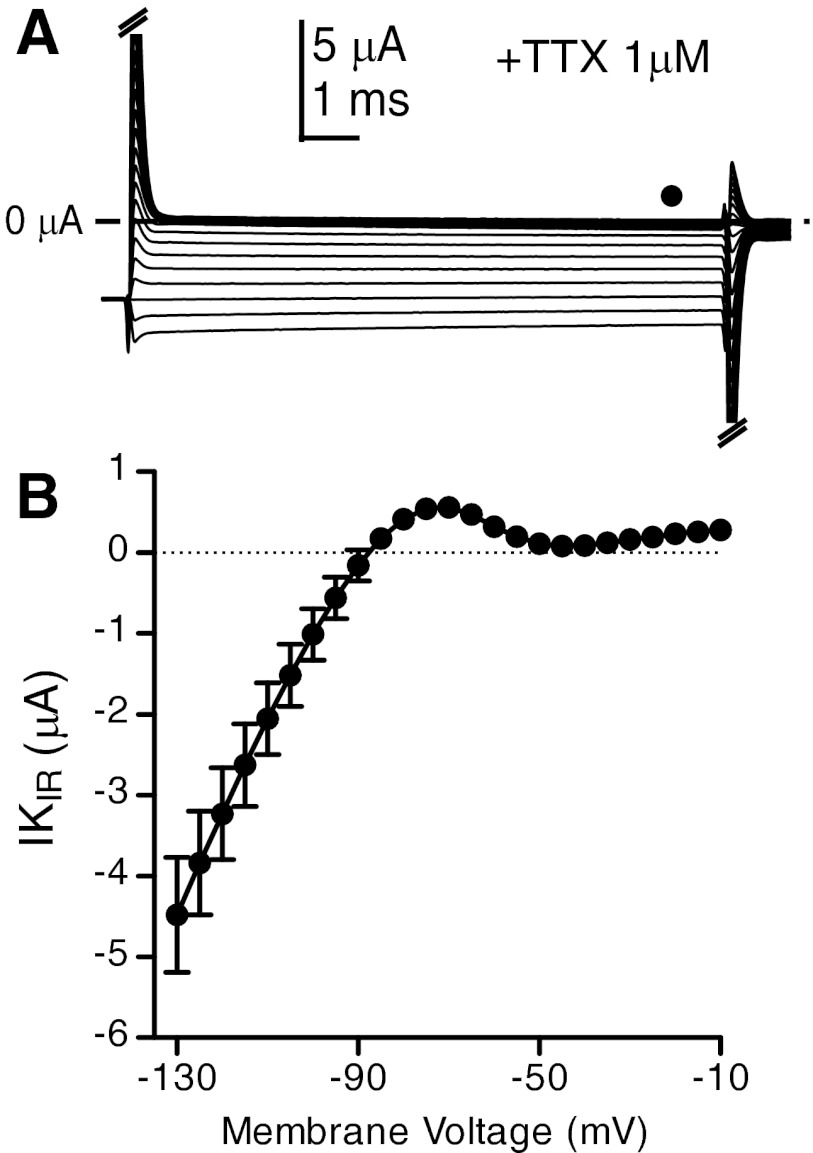

Addition of 1 μM TTX completely abolished INa and, to our surprise, also significantly reduced and sometimes eliminated the steady-state outward currents observed in the whole cell currents. Electrocytes in TTX showed primarily an inward rectifier K+ current (IKIR) (Fig. 4). Consistent with IKIR observed in related species (Ferrari and Zakon 1993), IKIR activates strongly at membrane potentials hyperpolarized below resting potential, becomes outward above resting potential, and is absent at potentials above −55 mV (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Electrocyte inward rectifier current (IKIR). A: representative voltage-clamp traces recorded in normal saline with 1 μM TTX, which eliminates all outward currents above −50 mV. Filled circle indicates point where steady-state current magnitude was measured for I-V plots. B: steady-state I-V plots (n = 4) show a large inwardly rectifying current with a small range where current becomes outward.

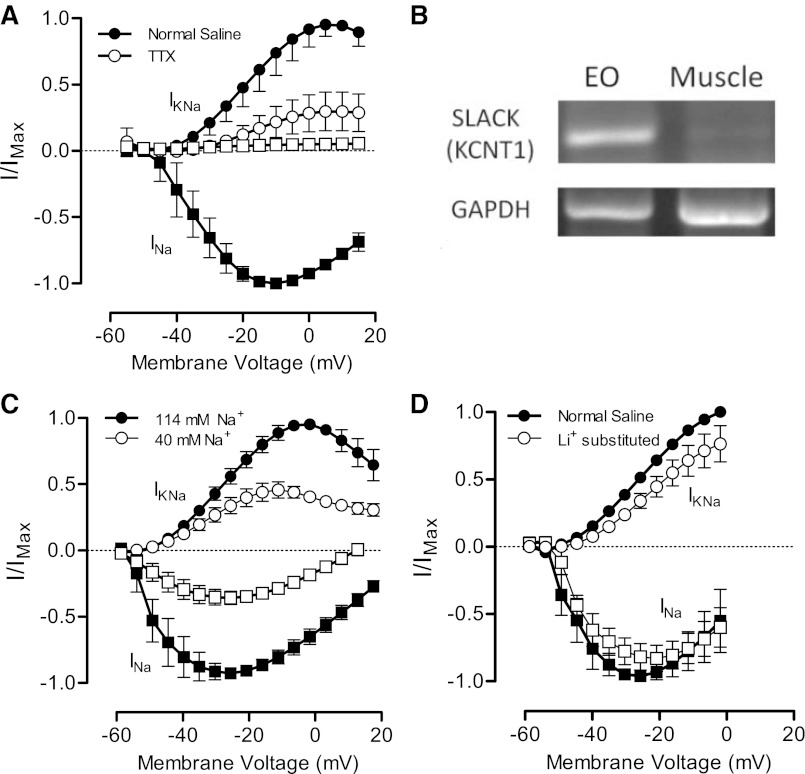

In addition to blocking INa, TTX also reduced significantly or eliminated altogether steady-state outward currents at membrane potentials above −55 mV (Fig. 4, Fig. 5A). We therefore hypothesized that these outward currents are mediated by a Na+-activated K+ current (IKNa), a current produced by two classes of KNa channel subunits, Slack and Slick (also referred to as Slo2.2 or KCNT1 and Slo2.1 or KCNT2, respectively) (Bhattacharjee et al. 2003; Yuan et al. 2003). Slack channels are activated by intracellular Na+ levels and often show an outwardly rectifying voltage dependence as we observed in our recordings (Fig. 2B, Fig. 5, A and C) (Yuan et al. 2003). Elimination or strong attenuation of putative IKNa in the presence of TTX suggests that this current is activated or potentiated when INa increases intracellular Na+.

Fig. 5.

The sustained outward current is a Na+-activated K+ channel (KNa). A: maximum outward current at steady state (circles) and peak transient inward current (squares) in normal saline (filled symbols) and after application of 1 μM TTX (open symbols). B: RT-PCR of cDNA from electric organ (EO) and muscle with primers against the KNa channel SLACK and the control gene GAPDH. PCR amplified a 479-bp fragment of SLACK only in EO. C: reduced extracellular Na+ (open symbols) decreases both inward current magnitude (squares) and outward current magnitude (circles) compared with baseline recordings in normal extracellular Na+ (filled symbols) (n = 5). D: complete substitution of Li+ for Na+ in extracellular saline does not significantly reduce the peak inward current magnitude but reduces magnitude of outward currents. Outward currents were normalized to values recorded during voltage steps to 0 mV in normal saline. We compared normalized outward currents during voltage steps to −25 mV, where INa is at its maximum. Normalized outward currents were 0.51 ± 0.0004 in normal saline and 0.34 ± 0.056 after Li+ substitution (t = 3.097, P = 0.04).

RT-PCR of EO and skeletal muscle revealed that Slack mRNA is expressed in EO but not muscle (Fig. 5B), thereby establishing the presence of at least one KNa channel isoform in EO. Electrophysiological results further support our conclusion that the high-voltage activated outward current is IKNa. Reducing extracellular Na+ from 114 mM to 40 mM decreased inward INa by ∼60% and produced a corresponding decrease in IKNa (Fig. 5C), indicating that the outward current is Na+ dependent. We also evaluated the Na+ dependence of the outward current by substituting all external Na+ with Li+ because Li+ readily permeates Na+ channels but is less effective than Na+ in activating KNa channels (Bischoff et al. 1998; Dryer 1994; Dryer et al. 1989). Li+ substitution commonly produces complete or near-complete elimination of IKNa in mammalian neurons (Safronov and Vogel 1996; Zhang et al. 2010), with more modest reductions of 15–20% in nonmammalian taxa (Dale 1993; Hartung 1985; Hess et al. 2007). Lithium substitution did not significantly reduce electrocytes' peak inward current but did reduce IKNa magnitude (Fig. 5D), further support that the outward current is indeed IKNa.

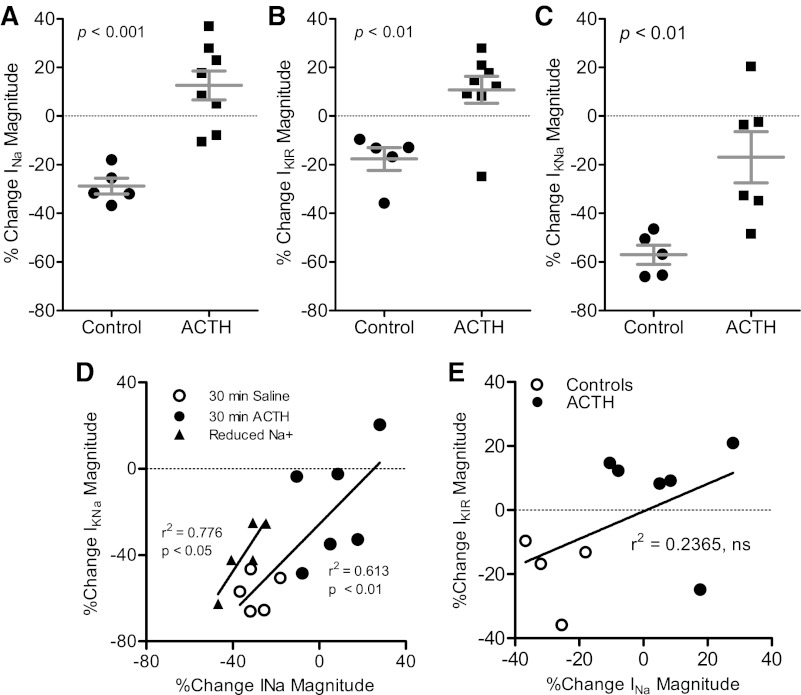

ACTH increases INa and IKIR magnitude.

Having identified the ion currents present in the electrocyte, we then evaluated the effects of ACTH on each of the three ion currents. In voltage-clamp experiments, bath application of ACTH increased the magnitude of INa, IKIR, and IKNa compared with controls (Fig. 6, A–C). Recordings of IKNa are only possible in preparations where INa is also present, raising the question of whether the observed increases in IKNa magnitude are a direct function of ACTH application or a secondary effect of the ACTH-induced enhancement of INa. We examined this possibility by linear regression of IKNa magnitude change on INa magnitude change across experimental conditions. For cells exposed to ACTH or control conditions, the change in IKNa magnitude was tightly correlated with the change in INa magnitude (Fig. 6D), suggesting that enhanced Na+ influx is at least partially responsible for the observed increases in IKNa. A similarly strong correlation of statistically indistinguishable slope was found for changes in INa and IKNa magnitude when we manipulated INa magnitude directly by reducing extracellular Na+ (Fig. 6D), additional evidence that suggests altered Na+ influx is responsible for the observed changes in IKNa magnitude. In contrast, the effects of ACTH on INa and IKIR magnitude are most likely independent. We found no correlation between INa and IKIR magnitude across ACTH versus control cells (Fig. 6E), and, most importantly, IKIR is active well below the activation potential for INa.

Fig. 6.

Application of ACTH increases the magnitude of INa, IKIR, and IKNa. A–C: % change from baseline in current magnitudes after 30-min exposure to ACTH or 30-min saline control. A: magnitude of peak INa is enhanced after 30-min application of ACTH in vitro; controls show large rundown of this current (df = 11, t = 5.137, P < 0.001). B: inward rectifier current magnitude increases with ACTH treatment and decreases in control cells, similar to results for INa (df = 11, t = 3.542, P < 0.01). C: IKNa magnitude decreases after 30-min ACTH exposure and after 30-min control conditions, but ACTH treatment produces a relative increase in IKNa compared with controls (t = 3.289, df = 9, P < 0.01). D: changes in INa magnitude are correlated with changes in IKNa magnitude in control cells (open circles) and cells treated with ACTH (filled circles) [F(1,9) = 14.24, P < 0.01]. Changes in INa magnitude induced by reducing external Na+ concentration are correlated with corresponding changes in IKNa magnitude (filled triangles and line) [F(1,3) = 10.44, P < 0.05]. The slopes of the 2 regressions are not different [F(1,12) = 0.287, P > 0.6]. E: changes in INa magnitude showed no correlation with changes in IKIR magnitude in control cells (open circles) and cells treated with ACTH (filled circles) [F(1,8) = 2.48, P > 0.15].

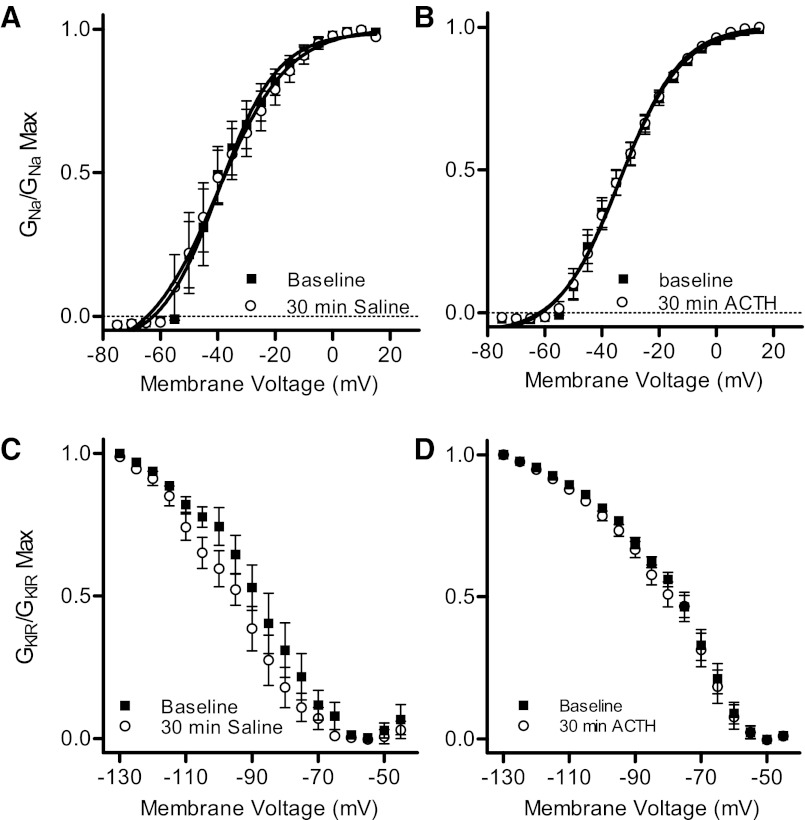

We found no other effects of ACTH on ion currents in the electrocyte. INa activation kinetics were unchanged by ACTH. Additionally, the voltage dependences of INa and IKIR were unaffected in both ACTH and control conditions (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

ACTH does not alter voltage dependence of INa or IKIR activation. A: G-V relationships for voltage-gated Na+ conductance shows no difference between baseline conditions and after 30-min exposure to control conditions [repeated-measures ANOVA, interaction F(1,18) = 0.182, P > 0.9]. B: voltage dependence of Na+ conductance is nearly identical at baseline and after 30-min ACTH treatment [repeated-measures ANOVA, interaction F(1,18) = 0.076, P > 0.9]. C: voltage dependence of inward rectifier conductance does not change from baseline after 30 min of control conditions. A repeated-measures ANOVA comparing across the range of greatest apparent difference (−120 mV to −65 mV) yielded no significant interaction [F(1,12) = 0.891, P > 0.5]. Even comparing only at −105 mV, the membrane potential with greatest apparent difference, we found no statistical significance: t(10) = 1.926, P = 0.083. D: voltage dependence of inward rectifier conductance is not changed by 30-min exposure to ACTH [repeated-measures ANOVA, interaction F(1,17) = 0.255, P > 0.9].

Numerical simulations predict that IKNa supports high-frequency APs and increased energy efficiency.

Rapidly firing cells, such as E. virescens electrocytes, require repolarizing K+ currents with very rapid activation kinetics, a role often filled by rapidly activating voltage-gated K+ currents. To investigate the functional significance of KNa rather than a classical delayed rectifier as the dominant repolarizing current in the present case, we conducted numerical simulations of electrocyte APs. We used a model cell that included a voltage-dependent Na+ current, an inwardly rectifying K+ current, and a KNa current. Parameters for the Na+ current and inward rectifier were derived from our empirical characterization of these currents in electrocytes. Kinetic parameters, voltage dependence, and Na+ sensitivity for the KNa current were derived from Slack-transfected cell lines and mammalian cells (Brown et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2007) as well as empirical measurements in the electrocytes.

Simulated whole cell currents (Fig. 8A) and simulated APs (Fig. 8B, left) showed good qualitative correspondence with whole cell currents recorded under voltage clamp (Fig. 2) and APs recorded in current-clamp conditions (Fig. 1). Interestingly, these simulations also showed a second AP at higher GNa, as we sometimes observed during current-clamp recordings. Increasing the voltage-gated GNa in the model increased AP amplitude by ∼10 mV for cells with IKNa present (Fig. 8B), as we found for the effects of ACTH on the AP in vitro (Fig. 1).

To compare the effects of the KNa currents on AP repolarization with those of traditional voltage-dependent delayed rectifier we first simulated model cells with a Na+-independent voltage-gated K+ (Kv) current with activation kinetics that exactly matched those of the IKNa current. This produced APs that were severely truncated in amplitude compared with those with Na+-sensitive K+ currents even as AP amplitude increased in response to increasing GNa (Fig. 8B, center). Truncation of APs occurred because the Kv current activated rapidly during the rising phase of the AP, as shown in Fig. 8C, center, which shows the time course of the Na+ current and the Kv current during a single AP. Substantial activation of the Kv current occurs before the peak of the AP, overlapping with the Na+ current and suppressing the rate of rise and peak of the resultant AP. In contrast, the same simulations for a cell with KNa current (Fig. 8C, left) demonstrate that the KNa current begins to activate only near the peak of the AP, which can therefore reach a peak near the equilibrium potential for Na+ ions (+50 mV).

These simulations predict that the integral of INa during the first AP in cells with KNa is ∼6–15 μA·mS over the range of Na+ currents simulated in Fig. 8B. Dividing this current integral (total Na+ charge movement during the AP) by the elemental charge on one Na+ ion (1.6 × 10−19 C) yields a predicted total influx of ∼3–9 × 1010 Na+ ions during each AP (Attwell and Laughlin 2001). Interestingly, the total influx of Na+ for simulated APs in the Kv-containing cells was generally 10–30% greater than for those with KNa current, even though those APs were of much lower amplitude.

Some mammalian central neurons, such as those in the auditory brain stem and certain interneurons, can fire at very high rates (up to 600–800 Hz). In these neurons, rapid firing is achieved by the expression of Kv3-family voltage-dependent K+ channels such as the Kv3.1 channel (Brown and Kaczmarek 2011). Under physiological conditions, these channels activate and deactivate very rapidly, but activation typically begins only at positive potentials (greater than −10 mV). As a result, the amplitude of APs in such rapid-firing mammalian neurons is generally small and the peak of APs usually occurs at potentials just positive to 0 mV. To test whether a mammalian Kv3-like current would allow high-frequency firing in the electrocyte model, we next replaced the KNa current with a current that matches the Kv3.1 current previously described in transfected cell lines and auditory neurons (Kaczmarek 2012; Song et al. 2005). The overall Kv3.1-like conductance was adjusted to give similar levels of K+ current activation during an AP (Fig. 8C, right). The Kv3.1-like current, like the KNa current, showed significant activation only at or near the peak of an evoked AP (Fig. 8C, right) and allowed APs to reach full amplitude (Fig. 8B, right).

We next compared the ability of the model electrocytes with KNa, KV, or Kv3.1-like current to maintain repetitive firing in response to high rates of stimulation. Simulations showed that electrocytes containing IKNa could indeed maintain firing frequencies of 500 Hz and that when GNa magnitude was doubled the AP amplitude during the train increased accordingly (Fig. 8D, left). Cells with KV currents could also follow these high rates of stimulation (data not shown), although as demonstrated above, AP amplitude was truncated by the Kv current. In contrast, electrocytes with the Kv3.1-like current could not maintain one-to-one firing during a 500-Hz stimulus train (Fig. 8D, right). Instead, APs were generated only in response to every other stimulus pulse. Simulations were carried out over a very wide range of Kv3.1-like conductances (2,000–40,000 μS) and Na+ current conductances (400–1,200 μS), and in no case could sustained firing at 500 Hz be obtained.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with our previous studies in a related species (Markham et al. 2009), we found that the melanocortin peptide ACTH increases AP amplitude in E. virescens electrocytes by increasing INa magnitude. Increasing AP amplitude (and therefore EOD amplitude) only during periods of activity allows animals to tune the energetic costs of EOD generation to immediate behavioral requirements. In contrast to previous reports, we found here a second potential mechanism for AP energy efficiency that complements the energetic regulation achieved by dynamic regulation of AP amplitude. By relying on KNa channels rather than voltage-gated K+ channels for AP repolarization, E. virescens electrocytes maintain high-frequency APs while avoiding the energetically wasteful overlap of depolarizing Na+ currents and repolarizing K+ currents.

Ionic currents of the Eigenmannia electrocyte.

We identified and characterized three ionic currents in Eigenmannia electrocytes, including a voltage-dependent Na+ current (INa) and an inward rectifier (IKIR), two currents observed in all gymnotiform electrocytes studied to date. INa displayed a small persistent component, consistent with reports of persistent electrocyte Na+ currents in other gymnotiform fish (Sierra et al. 2005). Interestingly, we found that the classical delayed-rectifier K+ current found in other species is not present in Eigenmannia electrocytes. We found instead a Na+-activated K+ current (IKNa) and characterized the properties of this conductance. This is the first report of such a current in gymnotiform electric fish, made all the more surprising by the fact that these currents are not expressed in EO of the closely related S. macrurus (Ferrari and Zakon 1993).

Rapid recovery of INa permits high AP frequencies.

As would be predicted from electrocytes' AP frequencies, our results show that INa of the Eigenmannia electrocyte shows ultrarapid recovery from inactivation, recovering completely in <1 ms (τrecov ∼0.3 ms at 25°C). This exceeds the rate of recovery in what was previously considered the fastest known current, INa of the calyx of Held in the mammalian medial trapezoid nucleus, where τrecov is 1.4 ms at 25°C and approaches 0.5 ms at 35°C (Leao et al. 2005). Rapid INa recovery ensures that, even with <1 ms to recover between APs when firing at the fastest EOD frequencies for this species (∼600 Hz), INa will be fully recovered between pulses. In addition, at the electrocyte's resting potential (−80 to −100 mV), INa suffers no steady-state inactivation.

Modulation of AP amplitude and electrocyte ion currents by ACTH.

We found that application of ACTH rapidly increased the magnitude of INa and IKIR. Our simulations (Fig. 8B) support the conclusion that changing INa density is sufficient to produce the AP amplitude modulations elicited in vitro by the application of ACTH. We also observed increases in the magnitude of IKNa following ACTH treatment, but our results indicate that this is primarily a function of increased Na+ influx in the presence of ACTH. We cannot, however, completely rule out direct effects of ACTH on KNa channels or channel trafficking. Both Slick and Slack KNa channels are directly modulated by intracellular signaling cascades and neuromodulators (Santi et al. 2006; Tejada et al. 2012), and the membrane trafficking of these channels can be regulated by cAMP/PKA pathways (Nuwer et al. 2010).

We observed a notable rundown of ionic current magnitudes and AP amplitude under control conditions. This is consistent with results of similar experiments in related species (Markham and Stoddard 2005; McAnelly and Zakon 1996; McAnelly et al. 2003) and is likely due to the removal of EO tissue from endogenous sources of the circulating melanocortin peptides that regulate current density and AP amplitude. Rundown does, however, appear to be more extreme for Eigenmannia electrocytes, perhaps as a function of higher metabolic demands.

A Na+-activated K+ conductance shapes brief APs and improves AP energy efficiency.

As is found in all other categories of excitable cells (Hille 1972), K+ conductances play a major role in shaping the pattern of excitability in gymnotiform electrocytes. The K+ currents of electrocytes from different gymnotiform species vary considerably. The outward K+ current of S. macrurus is a classic delayed rectifier that remains after TTX eliminates INa and is blocked by millimolar concentrations of TEA (Ferrari and Zakon 1993). The outward current of Gymnotus carapo is more complex, consisting of a TEA-sensitive outward rectifier and a 4-AP-sensitive A-type K+ current (Sierra et al. 2007). In the present studies, we found that the primary repolarizing K+ current in E. virescens electrocytes is a Na+-activated K+ current. To date, IKNa has not been identified in electrocytes of any other gymnotiform.

The rapidly activating KNa channels found in E. virescens electrocytes are important for providing a rapid and large repolarizing current to maintain the brief APs necessary in cells that maintain AP frequencies of several hundred hertz. Unlike the central nervous system, where information is encoded primarily by AP frequency and spike patterning, EOD amplitude is an essential feature for the signal's sensory and communication function in gymnotiform fish (Hopkins 1999). In E. virescens electrocytes, repolarization of APs by KNa channels allows INa to significantly depolarize the membrane before IKNa is activated by the transient buildup of internal Na+ ions, thereby producing very large-amplitude APs. This represents a novel functional role for KNa channels and contrasts with the situation in mammalian neurons that fire at comparably high rates (up to 600–800 Hz) such as those in the auditory brain stem, where repolarization is attributed to very rapid activation/deactivation of voltage-dependent Kv3-family K+ channels (Brown and Kaczmarek 2011).

Surprisingly, we found that substitution of a Kv3.1 current for the KNa current in simulations of EOD firing failed to allow the cells to follow a high rate of stimulation (500 Hz). Because the Kv3.1 current activates only at positive potentials (greater than −10 mV), it produced minimal shunting of the Na+ current during the rising phase of a single AP and, like the KNa current, allowed APs to peak at very positive potentials. The amount of Kv3.1 current required to repolarize rapidly the large-amplitude APs, however, results in a relative refractory period that prevents the occurrence of two consecutive full APs at high rates of stimulation. This is exactly the condition that occurs in simulations of mammalian phase-locking auditory neurons that express high levels of Kv3.1 (Kaczmarek 2012). Stimulation of such mammalian neurons at high rates such as 500 Hz can lead to sustained, precisely timed responses at 250 Hz. Another very important difference between rapid firing in electrocytes and central mammalian neurons is that rapidity of response but not AP amplitude is the primary biological concern for central neurons, and the peak of APs in these neurons does not typically reach more than 0–10 mV (Leao et al. 2008). Thus the kinetics and degree of activation of Kv3.1 during repetitive simulation will be quite different in the two systems.

Energetics of AP generation.

Our simulations predict that Eigenmannia electrocytes require a total influx of ∼3–9 × 1010 Na+ ions during each AP. The Na+-K+-ATPase requires one adenosine triphosphate (ATP) per 3 Na+ extruded, leading to a predicted metabolic cost of ∼1–3 × 1010 ATP molecules per AP, a value two to three orders of magnitude higher than early theoretical estimates for AP energetic costs in central neurons (Attwell and Laughlin 2001; Hallermann et al. 2012) and three orders of magnitude higher than recent empirical estimates (Alle et al. 2009; Carter and Bean 2009). This energetic cost per AP is not surprising given the electrocytes' extremely large size and the magnitude of their ionic currents. The EO of E. virescens consists of hundreds to thousands of electrocytes discharging at a rate of 200–600 Hz, further magnifying the energy required to produce the EOD on an ongoing basis as well as the potential benefits of regulating this energetic cost.

In our simulations, enhancing simulated AP amplitude with an increase in GNa produces an increase in predicted ATP consumption per AP that is directly proportional to the increase in GNa, while reducing AP amplitude by diminishing GNa produces a corresponding decrease in ATP consumption. Dynamic regulation of AP amplitude by controlling INa density is therefore potentially a mechanism for directly controlling energetic demands of EOD production, for example, by reducing these costs during periods of inactivity.

Interestingly, the total influx of Na+ for the simulations of full APs that were repolarized with the Na+-independent Kv current in Fig. 8 was generally 10–30% greater than for those with KNa current despite their lower-amplitude APs, highlighting the contribution of KNa channels to improving the energy efficiency of electrocyte APs. Repolarizing APs with KNa channels rather than Kv channels allows the AP to reach its peak before the onset of repolarizing KNa currents, thereby reducing energetically wasteful overlap of Na+ and K+ currents.

The extraordinary energetic requirement of AP generation in electrocytes suggests another role for the KNa channels expressed in electrocytes. Some KNa channels are inhibited by intracellular ATP (Bhattacharjee et al. 2003) and can thereby reduce electrical excitability to conserve energy when intracellular ATP is depleted faster than it can be replenished. We do not yet know whether the KNa channels expressed in E. virescens electrocytes are ATP sensitive, but ATP regulation of these KNa channels could be a mechanism underlying decreases in EOD amplitude that occur in low-oxygen conditions (Reardon et al. 2011). Another possibility is that activation of the KNa channel Slack, which directly interacts with the RNA-binding protein FMRP (fragile X mental retardation protein) serves to transduce changes in rapid firing into compensatory biochemical process such as the synthesis of new cellular components (Brown et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2012). These questions await full-length sequencing of Eigenmannia KNa channels and a detailed examination of their functional properties both in situ and in heterologous expression systems.

GRANTS

Financial support and equipment were provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant GM-084879 (H. H. Zakon) and NIH Grants DC-01919 and HD-067517 (L. K. Kaczmarek).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.R.M., L.K.K., and H.H.Z. conception and design of research; M.R.M. and L.K.K. performed experiments; M.R.M. and L.K.K. analyzed data; M.R.M., L.K.K., and H.H.Z. interpreted results of experiments; M.R.M. and L.K.K. prepared figures; M.R.M. and L.K.K. drafted manuscript; M.R.M., L.K.K., and H.H.Z. edited and revised manuscript; M.R.M., L.K.K., and H.H.Z. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maggie Patay for assistance with fish care and Ying Lu for assistance with PCR.

REFERENCES

- Alle H, Roth A, Geiger JR. Energy-efficient action potentials in hippocampal mossy fibers. Science 325: 1405–1408, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21: 1133–1145, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee A, Joiner WJ, Wu M, Yang Y, Sigworth FJ, Kaczmarek LK. Slick (Slo2.1), a rapidly-gating sodium-activated potassium channel inhibited by ATP. J Neurosci 23: 11681–11691, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff U, Vogel W, Safronov BV. Na+-activated K+ channels in small dorsal root ganglion neurones of rat. J Physiol 510: 743–754, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Kronengold J, Gazula VR, Spilianakis CG, Flavell RA, von Hehn CA, Bhattacharjee A, Kaczmarek LK. Amino-termini isoforms of the Slack K+ channel, regulated by alternative promoters, differentially modulate rhythmic firing and adaptation. J Physiol 586: 5161–5179, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Kronengold J, Gazula VR, Chen Y, Strumbos JG, Sigworth FJ, Navaratnam D, Kaczmarek LK. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls gating of the sodium-activated potassium channel Slack. Nat Neurosci 13: 819–821, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Kaczmarek LK. Potassium channel modulation and auditory processing. Hear Res 279: 32–42, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BC, Bean BP. Sodium entry during action potentials of mammalian neurons: incomplete inactivation and reduced metabolic efficiency in fast-spiking neurons. Neuron 64: 898–909, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crampton WG. Effects of anoxia on the distribution, respiratory strategies and electric signal diversity of gymnotiform fishes. J Fish Biol 53: 307–330, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Dale N. A large, sustained Na+- and voltage-dependent K+ current in spinal neurons of the frog embryo. J Physiol 462: 349–372, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer SE, Fujii JT, Martin AR. A Na+-activated K+ current in cultured brain stem neurones from chicks. J Physiol 410: 283–296, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer SE. Na+-activated K+ channels: a new family of large-conductance ion channels. Trends Neurosci 17: 155–160, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari MB, Zakon HH. Conductances contributing to the action potential of Sternopygus electrocytes. J Comp Physiol A 173: 281–292, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage TA, Salkoff L. Sodium-activated potassium channels are functionally coupled to persistent sodium currents. J Neurosci 32: 2714–2721, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn M, Heiligenberg W. Court and spark: electric signals in the courtship and mating of gymnotoid fish. Anim Behav 33: 254–265, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- Hallermann S, de Kock CP, Stuart GJ, Kole MH. State and location dependence of action potential metabolic cost in cortical pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci 15: 1007–1014, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung K. Potentiation of a transient outward current by Na+ influx in crayfish neurones. Pflügers Arch 404: 41–44, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess D, Nanou E, El Manira A. Characterization of Na+-activated K+ currents in larval lamprey spinal cord neurons. J Neurophysiol 97: 3484–3493, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. The permeability of the sodium channel to metal cations in myelinated nerve. J Gen Physiol 59: 637–658, 1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins CD. Design features for electric communication. J Exp Biol 202: 1217–1228, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner WJ, Tang MD, Wang LY, Dworetzky SI, Boissard CG, Gan L, Gribkoff VK, Kaczmarek LK. Formation of intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels by interaction of Slack and Slo subunits. Nat Neurosci 1: 462–469, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek LK. Gradients and modulation of K+ channels optimize temporal accuracy in networks of auditory neurons. PLoS Comput Biol 8: e1002424, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leao RM, Kushmerick C, Pinaud R, Renden R, Li GL, Taschenberger H, Spirou G, Levinson SR, von Gersdorff H. Presynaptic Na+ channels: locus, development, and recovery from inactivation at a high-fidelity synapse. J Neurosci 25: 3724–3738, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leao RN, Leao RM, da Costa LF, Rock Levinson S, Walmsley B. A novel role for MNTB neuron dendrites in regulating action potential amplitude and cell excitability during repetitive firing. Eur J Neurosci 27: 3095–3108, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macica CM, von Hehn CA, Wang LY, Ho CS, Yokoyama S, Joho RH, Kaczmarek LK. Modulation of the kv3.1b potassium channel isoform adjusts the fidelity of the firing pattern of auditory neurons. J Neurosci 23: 1133–1141, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham MR, Stoddard PK. Adrenocorticotropic hormone enhances the masculinity of an electric communication signal by modulating the waveform and timing of action potentials within individual cells. J Neurosci 25: 8746–8754, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham MR, McAnelly ML, Stoddard PK, Zakon HH. Circadian and social cues regulate ion channel trafficking. PLoS Biol 7: e1000203, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAnelly L, Zakon HH. Protein kinase A activation increases sodium current magnitude in the electric organ of Sternopygus. J Neurosci 16: 4383–4388, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAnelly L, Silva A, Zakon HH. Cyclic AMP modulates electrical signaling in a weakly electric fish. J Comp Physiol A 189: 273–282, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAnelly ML, Zakon HH. Coregulation of voltage-dependent kinetics of Na+ and K+ currents in electric organ. J Neurosci 20: 3408–3414, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwer MO, Picchione KE, Bhattacharjee A. PKA-induced internalization of slack KNa channels produces dorsal root ganglion neuron hyperexcitability. J Neurosci 30: 14165–14172, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon EE, Parisi A, Krahe R, Chapman LJ. Energetic constraints on electric signalling in wave-type weakly electric fishes. J Exp Biol 214: 4141–4150, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safronov BV, Vogel W. Properties and functions of Na+-activated K+ channels in the soma of rat motoneurones. J Physiol 497: 727–734, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar VL, Stoddard PK. Sex differences in energetic costs explain sexual dimorphism in the circadian rhythm modulation of the electrocommunication signal of the gymnotiform fish Brachyhypopomus pinnicaudatus. J Exp Biol 211: 1012–1020, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi CM, Ferreira G, Yang B, Gazula VR, Butler A, Wei A, Kaczmarek LK, Salkoff L. Opposite regulation of Slick and Slack K+ channels by neuromodulators. J Neurosci 26: 5059–5068, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta B, Stemmler M, Laughlin SB, Niven JE. Action potential energy efficiency varies among neuron types in vertebrates and invertebrates. PLoS Comput Biol 6: e1000840, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenkel S, Sigworth FJ. Patch recordings from the electrocytes of Electrophorus electricus. Na currents and PNa/PK variability. J Gen Physiol 97: 1013–1041, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra F, Comas V, Buno W, Macadar O. Sodium-dependent plateau potentials in electrocytes of the electric fish Gymnotus carapo. J Comp Physiol A 191: 1, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra F, Comas V, Buno W, Macadar O. Voltage-gated potassium conductances in Gymnotus electrocytes. Neuroscience 145: 453–463, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song P, Yang Y, Barnes-Davies M, Bhattacharjee A, Hamann M, Forsythe ID, Oliver DL, Kaczmarek LK. Acoustic environment determines phosphorylation state of the Kv3.1 potassium channel in auditory neurons. Nat Neurosci 8: 1335–1342, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejada M, Jensen LJ, Klaerke DA. PIP2 modulation of Slick and Slack K+ channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 424: 208–213, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Desai R, Kaczmarek LK. Slack and Slick KNa channels regulate the accuracy of timing of auditory neurons. J Neurosci 27: 2617–2627, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan A, Santi CM, Wei A, Wang ZW, Pollak K, Nonet M, Kaczmarek L, Crowder CM, Salkoff L. The sodium-activated potassium channel is encoded by a member of the Slo gene family. Neuron 37: 765–773, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brown MR, Hyland C, Chen Y, Kronengold J, Fleming MR, Kohn AB, Moroz LL, Kaczmarek LK. Regulation of neuronal excitability by interaction of fragile X mental retardation protein with slack potassium channels. J Neurosci 32: 15318–15327, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Rosenhouse-Dantsker A, Tang QY, Noskov S, Logothetis DE. The RCK2 domain uses a coordination site present in Kir channels to confer sodium sensitivity to Slo2.2 channels. J Neurosci 30: 7554–7562, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]