Abstract

Background

Current recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) are that individuals should seek to maintain a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5–25 kg/m2, independent of age. However, there is an ongoing discussion whether the WHO recommendations apply to old (70 ≥ 80 years) and very old persons (80+ years). In the present study we examine how BMI status and change in BMI are associated with mortality among old and very old individuals.

Design

Pooled data from three multidisciplinary prospective population-based studies OCTO-twin, GENDER, and NONA.

Setting

Sweden.

Participants

882 individuals aged 70 to 95 years.

Measurements

Body Mass Index was calculated from measured height and weight as kg/m2. Information about survival status and time of death was obtained from Swedish Civil Registration System

Results

Mortality hazard was 20% lower for the overweight group relative to the normal/underweight group (RR = 0.80, p< .05), and the mortality hazard for the obese group did not differ significantly from the normal/underweight group (RR = 0.93, > .10), independent of age, education, and multimorbidity. Furthermore, mortality hazard was 65% higher for the BMI loss group than for the BMI stable group (RR = 1.65, p< .001) and 53% higher for the BMI gain group than for the BMI stable group (RR = 1.53, p≤ .001). However, the BMI change differences were moderated by age, i.e., the higher mortality risks associated with both loss in BMI and BMI gain were less severe in very old age.

Conclusion

Old persons who were overweight had a decreased mortality risk compared to old persons having a BMI below 25, even after controlling for weight change and multimorbidity. Compared to persons who had a stable BMI those who increased or decreased in BMI had a higher mortality risk, particularly among people aged 70 to 80. This study lends further support for the opinion that the WHO guidelines are overly restrictive in old age.

Keywords: Aging, Body Mass Index, Mortality, Obesity, Survival, Underweight

Background

Being of normal weight is health ideal across all age groups. Current recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) are that individuals should seek to maintain a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5–25 kg/m2, independent of age.1 This recommendation is based, in part, on well established findings that higher BMI in midlife is associated with decreased survival. However, there is an ongoing discussion in the literature whether the WHO recommendations do actually apply to old and very old persons.

Gerontologists have studied associations between BMI and mortality outcomes for many years. Comprehensive reviews of the empirical literature tentatively conclude that in old age, lower BMI, rather than higher BMI (overweight and obese), is associated with significantly higher mortality risks.2, 3 These reviews highlight that before stronger conclusions are warranted, several challenges need to be addressed more thoroughly, including the influence of change in BMI and gender, whether the noted associations hold among the very old segment of the population, and with objective (rather than self-report) measures of BMI.2, 3

During old age, the association between BMI and survival may be driven by changes in BMI, rather than BMI itself. For example, low BMI may simply be a symptom of disease-related BMI loss – with the BMI loss, itself, being the better indicator of mortality risk. A number of studies have found that BMI loss in late life is associated with an increased mortality risk,4–8 although the findings are not consistent.8 In midlife, BMI gain is associated with decreased survival. Although some findings suggest that this also holds in late life,4, 9 other studies suggest that gain in BMI among the elderly is not associated with mortality.8, 10, 11

The mixed findings may result from a variety of methodological issues, including attempts to generalize across samples that span a wide age range.5 For example, in the young old (e.g. age 65) gain in BMI might be a manifestation of increased health risks (e.g., sedentary behavior), while among the very old gain in BMI might be an affordance of health (e.g., body still is able to benefit from nutrients). In sum, changes in BMI may be indicative of different processes among the young old and the very old (e.g. age 85) and thus might have different implications for mortality risk at different ages. Supporting this notion, weight gain was associated with an increased mortality risk among the young old participants in the Rotterdam Aging Study, but not among the very old participants.9

In the present study we push the age-related differentiation a bit further and examine how BMI status and change in BMI are associated with mortality among old (70 years to 80 years) and very old (80 years and older)

METHOD

Study population

To examine associations between BMI, change in BMI, and survival, we pooled data across three multidisciplinary population-based studies from Sweden: OCTO-twin,12 GENDER,13 and NONA.14 These studies were designed and managed by overlapping teams of researchers, and the across-study consistency of sampling procedures, measures, and protocols, has allowed for pooling and integrated analysis of the data. All studies involved prospective data collected by trained research nurses in the respondents’ home at approximately two-year (OCTO-twin, NONA) or four-year (GENDER) intervals from individuals aged 70 to 95 years who were living in either ordinary housing or institutional housing. The original studies were each approved by research ethics committees at the Karolinska Institutet (OCTO-twin and GENDER) and Linköping University (NONA).

Participants and Procedure

Participants in OCTO-twin and GENDER were recruited from the Swedish Twin Registry that lists all instances of multiple births in the country.15 OCTO-twin is a representative sample of all intact, same-sex twin pairs (mono- and dizygotic) aged 80 years and above at baseline. GENDER is a representative sample of unlike-sex twins aged 70–79 years at baseline. Relative to representative samples of same-aged singletons, twin samples identified from the twin registry were similar to non-twins in vitality, well-being, physical and cognitive functioning, and health utilization.16 In NONA individuals age 86, 90, and 94 years were selected randomly from the population registry containing the names and birth dates of all residents in the municipality of Jönköping, Sweden. This region includes rural, suburban, and urban settings and is considered representative of the variety of living situations throughout the nation. Across the studies, more than 80% of initially contacted individuals agreed to participate for a pooled sample of N = 1581.

Included in the present analyses were 882 participants whose height and weight were assessed on two occasions, the first and the second in-person testing (IPT) of the respective study (see above), and who provided data on all the correlates of interest (listed below). As one would expect, relative to the drop-outs, participants included in our sample were younger, M = 80.09, SD = 5.74 vs. M = 82.55, SD = 6.26; F(1, 1,355) = 53.2, p< .001 and lived longer, M = 8.05 years, SD = 3.82 vs. M = 3.24, SD = 3.32; F (1, 1,118) = 475.5, p< .001. No differences were found between the participants and the drop-outs on the BMI at initial assessment (IPT1), gender proportion, education, and number of medical conditions (p> .10).

Body Mass Index Status

Height and weight were assessed by trained research nurses during IPT. Weight was assessed with calibrated mechanical scales across all three studies. To account for the extra weight of clothing, one kilogram was extracted from the measured weight. The repeated measures of BMI were calculated as weight (kg) divided by squared height (m). Following the WHO guidelines,1 initial levels of BMI were categorized into four weight status categories: underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5≤BMI<25 kg/m2), overweight (25≤BMI<30 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2). With only 35 participants (4%) having initial BMI below 18.5, this group was merged with the normal group (also justified by preliminary analysis indicating that the groups did not differ in mortality risk).

Change in Body Mass Index

The two repeated measures of BMI were used to calculate a proportional change score for each individual, ΔBMI = 100*(BMI2 – BMI1)/ BMI1 (Scores from GENDER divided by two to account for four-year vs. two-year follow-up). Substantial weight change among adults is often defined as a weight change of ± 3%.17 However, in ageing research, definitions of substantial weight change range from ± 3% to ± 5%.7, 10, 11, 18 Taking a conservative approach, we categorized individuals into three categories based on their BMI change scores: BMI loss (ΔBMI ≤ −5%), BMI stable (−5% <ΔBMI < +5%), and BMI gain (ΔBMI ≤ +5%). Proportions and characteristics of the resulting three categories of BMI change are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Variables under Study.

| BMI level |

BMI change |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight and normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2) |

Overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2) |

Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) |

BMI loss(−5%) | Stable BMI | BMI gain (+5%) | |

| n | 459 | 318 | 105 | 211 | 533 | 138 |

| Age | 81.39a (5.64) | 78.77b (5.61) | 78.4b (5.19) | 80.44a (5.21) | 79.80a (5.82) | 80.66a (6.13) |

| n (%) women | 288a (63%) | 172b (54%) | 67a (64%) | 137a (65%) | 308a (58%) | 82a (59%) |

| Education | 7.44a (2.42) | 7.22a,b (2.35) | 6.70b (1.52) | 6.98a (2.09) | 7.44b (2.43) | 7.06a,b (2.16) |

| Multimorbidity | 1.23a (1.28) | 1.51b (1.43) | 1.38a,b (1.34) | 1.53a (1.45) | 1.26b (1.32) | 1.42a,b (1.29) |

Note. N = 882. Means (standard deviations) and frequencies (percentages) are shown. Columns that do not share the same superscript are different from one another at p< .05, based on Bonferroni adjustments.

Mortality

Information about survival status and time of death for deceased participants was obtained from Swedish Civil Registration System, which registers date of death of all Swedish persons. Of the 882 participants included in our analyses, a total of 667 participants (or 75%) had died during the 18 years of follow-up. On average, deceased participants were 81.11 years of age at the initial assessment (SD = 5.14, range 70 – 95) and died 8.05 years later (SD = 3.82, range 1 – 18).

Demographics and Multimorbidity

Chronological age was recorded at the initial assessment as number of years since birth (M = 80.11, SD = 5.73, range 70–95). For the purpose of analyzing the age-related differentiation, the cohort was split on the sample mean, into old (range 70 to 80 years of age) and very old (age 80+) individuals. Participants reported on the number of years of formal education (M = 7.27, SD = 2.31, range 0–20). Multimorbidity, as an indicator of overall physical health, was measured as the number of diseases and medical conditions an individual had at the time of the initial interview. Reports were obtained from the participants by nurse interviewers who reviewed medical information with participants and, when necessary, family informants.13 Such self-reports of medical conditions are often consistent with physicians’ diagnoses.19, 20 Specific disease diagnoses included arthritis, hip fracture, osteoporosis, stroke, heart attack, chest pain/angina, diabetes, asthma, coughing with yellow phlegm, malignant tumor, and Parkinson’s disease. On average this sample carried M = 1.36 (SD = 1.35, range 0–8) diagnoses.

Data Analysis

Our main interest was to examine whether and how BMI status and BMI change were associated with mortality among a sample of old and very old individuals. To do so, we applied proportional hazard regression models to the pooled 18-year follow-up data. The model took the form

| (1) |

where logh(tij) is the log of individual i’s risk of dying (or log hazard: logh) at time t. Logh0(tj) is the baseline log hazard function, the time-dependent risk of dying, when all other predictors are zero (i.e., for average person of normal, stable BMI). Parameters β1 through β8 indicate the differences in log hazard between BMI status and BMI change categories, the association between, age, education, gender, and comorbidities and the log hazard, and β9–12 indicates the extent to which age moderated those differences and associations. Age was centered at 80 years, and scores for all measures and groups were effect-coded/centered so that mortality hazards do not refer to a specific group, but the overall sample. We tested all the age interactions and in the final model only retained only those that were reliably different from zero with α = .05. Models were estimated using SAS (PROC PHREG).21

RESULTS

Proportions and characteristics of the three categories of BMI status and BMI change are given in Table 1. There were overall differences in age F (2, 879) = 26.08, p<.0001, gender differences, χ2(2, N=879) 6.67, p = 0.04, education F (2, 879) = 4.60, p =.01, and multimorbidity F (2, 879) = 3.89, p =.02 between the BMI status groups, Comparisons between those who maintained or changed their BMI showed no overall differences in age F (2, 879) = 1.77, p =.17 or gender χ2(2, N=879) 3.21, p = 0.20. However, there were overall differences in education F (2, 879) = 3.57, p =.03, and multimorbidity F (2, 879) = 3.07, p =.05. Comparisons between three BMI status and BMI change groups, based on Bonferroni adjustments, are shown in Table 1.

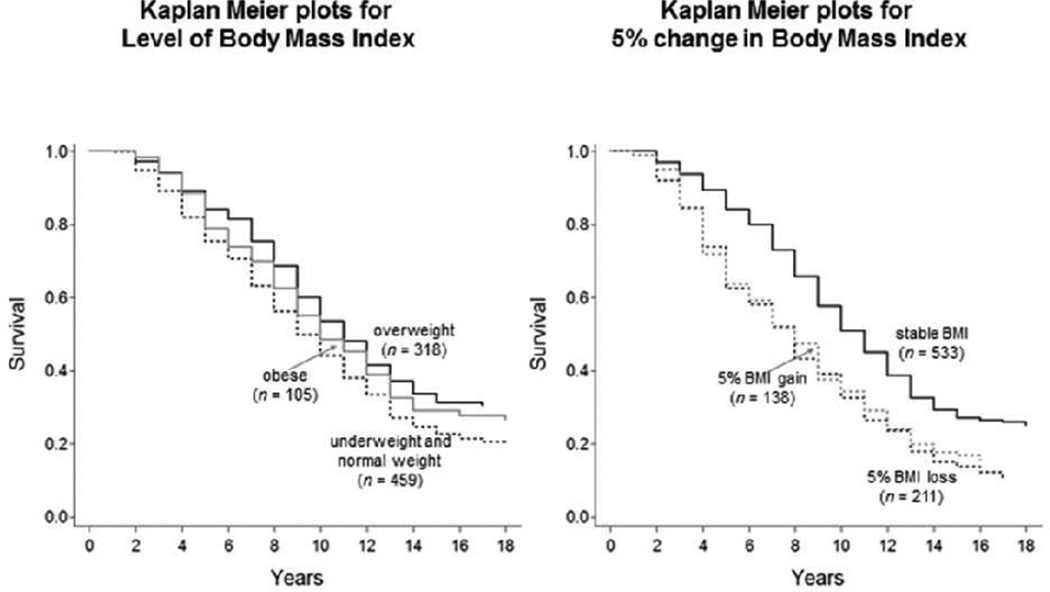

Results from the final model are presented in Table 2. As expected, older age (RR = 1.11), being a man (RR = 0.61), and higher multimorbidity (RR = 1.16, all p’s < .05) were all related to higher mortality hazards. Most important for our research question, there were significant differences in mortality hazard associated with BMI status and BMI change. Specifically, independent of other effects, mortality hazard was 20% lower for the overweight group relative to the normal/underweight group (RR = 0.80, p< .05). However, mortality hazard for the obese group did not differ significantly from the normal/underweight group (RR = 0.93, > .10). Mortality hazard was 65% higher for the BMI loss group relative to the BMI stable group (RR = 1.65, p< .05); and 53% higher for the BMI gain group relative to BMI stable group (RR = 1.53, p< .05). The differences in survival are shown in Figure 1. The left panel illustrates the differences in expected survival time between the BMI status categories, with overweight participants dying, on average, almost a full year later than those with normal/underweight status. The right panel illustrates the differences in expected survival time between the BMI change categories, with the BMI stable group living more than a full year longer than the BMI loss group.

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios for 18-Year Mortality by Body Mass Index and Correlates.

| Predictors | HR | [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| BMI level | ||

| Underweight and normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2) | – | – |

| Overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2) | 0.80* | [0.67–0.95] |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 0.93 | [0.71–1.22] |

| BMI change | ||

| 5% loss in BMI | 1.65* | [1.34–2.04] |

| BMI stable | – | – |

| 5% BMI gain | 1.53* | [1.18–1.99] |

| Age | 1.11* | [1.09–1.13] |

| Women | 0.61* | [0.52–0.72] |

| Education | 1.00 | [0.96–1.03] |

| Multimorbidity | 1.16* | [1.10–1.23] |

| Age × 5% BMI loss | 0.93* | [0.89–0.96] |

| Age × 5% BMI gain | 0.89* | [0.85–0.92] |

Note. CI = confidence interval. The underweight and normal weight group and the stable weight group served as the reference. Age was centered at 80 years, and scores for all measures and groups were effect-coded/centered so that mortality hazards do not refer to a specific group, but the overall sample.

p< .05.

Figure 1.

Survival probabilities over 18 years are shown for groups of older Swedish participants with different levels and rates of change in Body Mass Index. The left-hand Panel illustrates that hazard ratios of mortality were lower for overweight participants relative to those underweight or with normal weight. Average group differences in survival time amount to almost a full year, after residualizing for age, gender, education, and comorbidities. The right-hand Panel shows that hazard ratios of mortality were higher for participants with 5% loss in BMI relative to those with stable BMI. Average group differences in survival time amount to more than a full year, after residualizing for age, gender, education, and comorbidities.

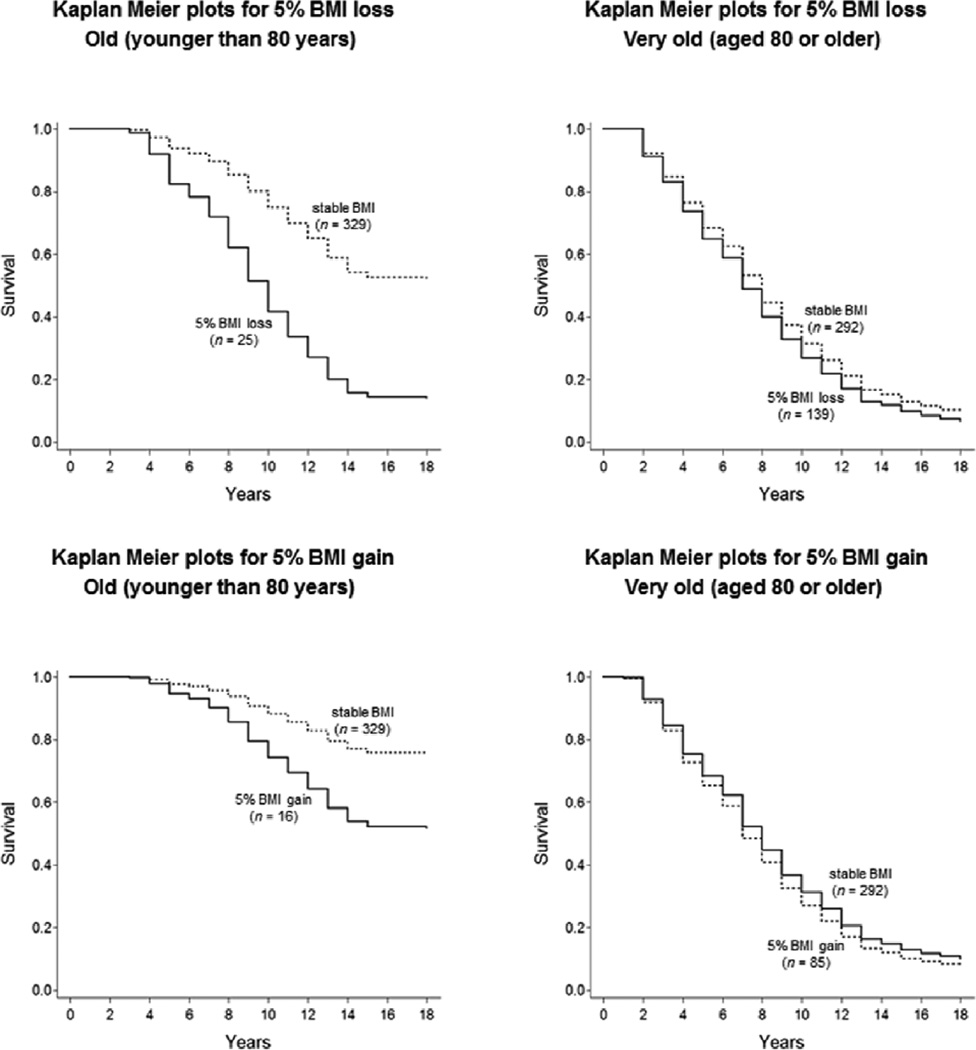

Of additional interest were the age interactions. As seen in Table 2, the BMI change differences were moderated by age. That is, the higher mortality risks associated with both loss in BMI and BMI gain were less severe in very old age (age × BMI loss: RR = 0.93; age × BMI gain: RR = 0.89, ps < .05). Differences between the survival curves for typical BMI stable and BMI loss of individuals above or below age 80 (the sample mean) are shown in Figure 2. The detrimental effects of BMI change for mortality are discernible in old age, (left panel), but not so much in very old age (right panel).

Figure 2.

Illustrating differences between participants with 5% BMI loss (upper Panels) or 5% BMI gain (lower Panels) relative to those with stable BMI, separately for people above and below age 80. The detrimental effects of BMI change for mortality are only discernible among people in their 70s (see left-hand Panels), but not among people in their 80s and beyond (see right-hand Panels of Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the effect of BMI and change in BMI with all-cause mortality among older adults, and specifically in a sample with a high percentage of the very old. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated BMI change in relation to mortality among the very old. Our results suggest that being overweight relates to lower mortality risk in old and very old age. In addition, change in BMI (either gain or loss) increases mortality risk. However, the effects differ considerably with age in that with advancing age the detrimental effects of change in BMI are getting smaller and become non-significant. It appears as if BMI change becomes less of a distinctive feature in advanced ages that is associated with mortality.

This study further supports the opinion that persons being overweight according to the WHO guidelines might not be at an increased risk of mortality.2, 3 In our study, individuals classified as being overweight by the WHO standards, were at a decreased risk of mortality. The advantage with being overweight could be explained by that the fat mass stores energy that can be used during negative energy balance. Actually, while being overweight and/or obese are risk factors of several diseases among prevalent cases of, for example, congestive heart failure, individuals with higher BMI scores have the best survival.22 The finding that persons being overweight were at a lower mortality risk remained significant when change in BMI and multimorbidity were controlled for, which indicates that the reversed association between BMI and mortality in late life can not only be due to underlying diseases causing weight change, which often is proposed as a potential causal pathway for this seemingly reversed association. The critical reader could argue that the association between a low BMI and an increased mortality risk were probably driven by those persons with the lowest BMI, but we did not find any significant difference between the underweight and normal weight group in mortality risk, hence it is not likely that the association was driven by those with the lowest BMI.

Both BMI gain and BMI loss were associated with an increased mortality risk. It has been hypothesized that BMI stability in old age is a sign of health, and a sign that the body is able to maintain homeostasis, and accordingly both BMI decrease and BMI increase are suggestive of systemic breakdown.23 Further, loss in BMI in old age might be a sign of the body’s inability to take up and benefit from nutrients. Declining BMI might also be a manifestation of poorer psychological and emotional well-being, in that reported symptoms include loss of appetite and/or loss of enjoyment of food. Persons with higher BMI are also at a reduced risk of hip fractures, and thereby at a reduced risk of death due to surgical and postoperative complication,24 as the adipose tissue reduces impact forces if case of a fall.25 It is also worth mentioning that even if an older person regains weight, the lean mass is not often not totally regained, and accordingly, the older person might become sacropenic.18 Except for all the common reasons for increase in BMI, such as high caloric diet and low energy expenditure, gain in BMI in old age might also be a side effect due to medication use or physical limitations.

However, it is important to point out that the negative effects of BMI change were especially pronounced in the younger age segment of this study, i.e. those younger than 80 years. A possible explanation is that there in general were a difference in the follow-up time between the old and very older age segments of this study, with a four-year follow-up time for those younger than 80 years and two-years follow-up for those older than 80 years. Two years might be too short a follow-up time to capture change in BMI, if the changes are small and insidious. Indeed, our preliminary analyses of multi-wave change in the BMI among old and very old Swedish adults revealed that within-person change was only minimal as compared with the cross-sectional between-person differences (e.g., intraclass correlation larger than .80). Another reason why we may not have found associations between change in BMI and increased mortality among the very old is that those with worse health and more weight loss might have dropped out earlier from the study, or been unable to measure at follow-up (research nurses were not always able to assess weight and height for those who had become bedridden or who were in wheelchairs). More studies on weight change among the very old are warranted.

We also analyzed the interaction between BMI level, BMI change, and multimorbidity, and found no significant interaction terms. Furthermore, no significant interaction between BMI level, BMI change, and gender were found, supporting a meta-analysis which also did not report any substantial gender differences.3

The strength of this study is the large population-based prospective sample with known death dates using BMI based on assessed weight and height among the old and very old. Although BMI is widely used as a measure of body fat, BMI is criticized as a less effective assessment of body fat in old age. While some might suggest our findings are related to issues of measurement, a recent study using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry assessing total fat mass among men also showed an association between loss of total fat mass and decreased survival,7 i.e., studies using different assessments methods of fat mass receive similar results. One potential limitation is that we did not know whether the decline in BMI was intentional or not. Although intentional weight loss might have different origin than unintentional weight loss, the evidence for a positive effect of intentional weight loss on life expectancy in late life is weak.6 Although we had information about medical conditions, in old age there are a lot of unrecognized health problems that might have affected the association. Finally, as in all studies that include old persons, there is a selection bias for those who are healthier, and/or for overweight or obese individuals who are less sensitive to the negative effects of being overweight or obese.

In conclusion, old persons who were classified as overweight based on their BMI had a decreased mortality risk compared to old persons having a BMI below 25, even after controlling for weight change and multimorbidity. Compared to persons who had a stable BMI, those who gained or lost weight over a two or four year period had a higher mortality risk. This study lends further support for the opinion that the WHO guidelines considering BMI are overly restrictive in old age. In addition, stable BMI might be an indicator of good health in old age, and clinicians should probably record and pay at least as much attention to changes in BMI, as well as to the BMI value in itself.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to the original principal and co-investigators of the Swedish datasets; Steven Zarit and Gerald McClearn from Pennsylvania State University, Boo Johansson from the University of Göteborg, Bo Malmberg and Stig Berg (deceased) Jönköping University, and Nancy L. Pedersen from Karolinska Institutet. We greatly appreciate the efforts of interviewers and the research teams at the Institute of Gerontology, School of Health Sciences at Jönköping University in Sweden, the Center for Developmental and Health Genetics at the Pennsylvania State University, and the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden for their design and collection of the original data.

Funding: The authors gratefully acknowledge funds provided by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS) (post doc grant 2010-0704 and Future Leaders of Aging Research in Europe (FLARE) post doc grant 2010-1852), the Center for Population Health and Aging at Penn State University (NIH/NIA Grant R03 AG028471) and National Institute on Aging (NIA) (R21-AG033109, RC1-AG035645, R21-AG032379, RC1-AG035645, R21-AG032379, R21-AG004132) to combine the datasets and conduct analyses. The data collection of the OCTO-twin Study was supported by NIA (AG08861). Further, the data collection of the Gender Study was supported by the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Aging, Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson’s Foundation, FAS, Swedish Foundation for Health Care Sciences and Allergy Research, and the King Gustaf V and Queen Viktoria Foundation. Nona was supported by grants from FAS and Vardal Foundation for Health Care and Allergy Research.

Sponsor’s Role: None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Anna K. Dahl was responsible for drafting the manuscript. She is the corresponding author. Elizabeth B. Fauth designed and pooled the data. Denis Gerstof analyzed the data. Anna K. Dahl, Elizabeth B. Fauth, Marie Ernsth-Bravell, Linda B. Hassing, Nilam Ram and Denis Gerstof are all responsible for the intellectual content of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity - preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heiat A, Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM. An evidence-based assessment of federal guidelines for overweight and obesity as they apply to elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1194–1203. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janssen I, Mark AE. Elevated body mass index and mortality risk in the elderly. Obes Rev. 2007;8:41–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somes GW, Kritchevsky SB, Shorr RI, et al. Body mass index, weight change, and death in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:132–138. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrada MM, Kawas CH, Mozaffar F, et al. Association of body mass index and weight change with all-cause mortality in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:938–949. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrington M, Gibson S, Cottrell RC. A review and meta-analysis of the effect of weight loss on all-cause mortality risk. Nutr Res Rev. 2009;22:93–108. doi: 10.1017/S0954422409990035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CG, Boyko EJ, Nielson CM, et al. Mortality risk in older men associated with changes in weight, lean mass, and fat mass. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehmann AB, Bassey EJ. Longitudinal weight changes over four years and associated health factors in 629 men and women aged over 65. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50:6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deeg DJ, Miles TP, Van Zonneveld RJ, et al. Weight change, survival time and cause of death in Dutch elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1990;10:97–111. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(90)90048-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman AB, Yanez D, Harris T, et al. Weight change in old age and its association with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1309–1318. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds MW, Fredman L, Langenberg P, et al. Weight, weight change, mortality in a random sample of older community-dwelling women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1409–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClearn GE, Johansson B, Berg S, et al. Substantial genetic influence on cognitive abilities in twins 80 or more years old. Science. 1997;276:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5318.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold C, Malmberg B, McClearn G, et al. Gender and health- a study of older unlike-sex twins. J Geron: Soc Sci. 2002;57B:168–176. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.s168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fauth EB, Zarit SH, Malmberg B, et al. Physical, cognitive, and psychosocial variables from the disablement process model predict patterns of change in disability for the oldest-old. Gerontologist. 2007;47:613–624. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenstein P, De faire U, Floderus B, et al. The Swedish Twin Registry: A unique resource for clinical, epidemiological and genetic studies. J Intern Med. 2002;252:184–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simmons SF, Ljungquist B, Johansson B, et al. Selection bias in samples of older twins? A comparison between octogenerian twins and singletons in Sweden. J Aging Health. 1997;9:553–567. doi: 10.1177/089826439700900407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens J, Truesdale KP, McClain JE, et al. The definition of weight maintenance. Int J Obes. 2006;30:391–399. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JS, Visser M, Tylavsky FA, et al. Weight loss and regain and effects on body composition: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:78–83. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsson SE, Johansson B, Berg S, et al. A comparison of diagnosis capture from medical records, self-reports, and drug registrations: A study in individuals 80 years and older. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002;14:178–184. doi: 10.1007/BF03324433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simpson CF, Boyd CM, Carlson MC, et al. Agreement between self-report of disease diagnoses and medical record validation in disabled older women: Factors that modify agreement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:123–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SAS Institute Inc. SAS system for Microsoft Windows. 9.1 edn. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anker SD, Coats AJ. Cardiac cachexia: A syndrome with impaired survival and immune and neuroendocrine activation. Chest. 1999;115:836–847. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold AM, Newman AB, Cushman M, et al. Body weight dynamics and their association with physical function and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:63–70. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser JH. Survival of the fattest. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong ME, Spencer EA, Cairns BJ, et al. Body mass index and physical activity in relation to the incidence of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1330–1338. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]