Abstract

Securin overexpression correlates with poor prognosis in various tumours. We have previously shown that securin depletion promotes radiation-induced senescence and enhances radiosensitivity in human cancer cells. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms and the paracrine effects remain unknown. In this study, we showed that radiation induced senescence in securin-deficient human breast cancer cells involving the ATM/Chk2 and p38 pathways. Conditioned medium (CM) from senescent cells promoted the invasion and migration of non-irradiated cancer and endothelial cells. Cytokine assay analysis showed the up-regulation of various senescence-associated secretory phenotypes (SASPs). The IL-6/STAT3 signalling loop and platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB)/PDGF receptor (PDGFR) pathway were important for CM-induced cell migration and invasion. Furthermore, CM promoted angiogenesis in the chicken chorioallantoic membrane though the induction of IL-6/STAT3- and PDGF-BB/PDGFR-dependent endothelial cell invasion. Taken together, our results provide the molecular mechanisms for radiation-induced senescence in securin-deficient human breast cancer cells and for the SASP responses.

Cellular senescence is a permanent cell cycle arrest that was initially described as the terminal phase of primary human cell populations that cannot be stimulated to return to the cell cycle by growth factors. Therefore, senescence is viewed as a tumour-suppressive mechanism that prevents cancer cell proliferation1,2. Diverse factors, such as oxidative damage, telomere dysfunction, DNA damage response caused by ionising radiation and several chemotherapeutic drugs can trigger irreversible cellular senescence3. It has been shown that DNA damage activates the p53 tumour suppressor protein that either orchestrates transient cell cycle inhibition, which allows for DNA repair, or prevents cell proliferation by triggering cellular senescence or apoptosis4. To date, senescence has been shown to depend on the p53/p21 pathway for senescence onset and on the p16INK4a/pRb pathway for senescence maintenance5. However, studies have also revealed a p53-independent senescent pathway in response to DNA damage6,7,8.

Although senescence might be a potential tumour suppressive mechanism, senescent cells remain metabolically active and have undergone widespread changes in protein expression and secretion, ultimately developing senescence-associated secretory phenotypes (SASPs)9. SASPs include cytokines and chemokines (such as IL-1α/β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-2 and MIP-1α), growth factors (such as bEGF, EGF and VEGF), several matrix metalloproteinases and nitric oxide9. SASPs have many paracrine effects, including tumour suppression, tumour promotion, aging and tissue repair, some of which have apparently opposing effects10. It is possible that the secretory characteristics of SASPs are dependent on cell type and cellular context11. Despite considerable progress in the investigation of senescence, far less is known regarding SASP regulation12.

Securin, also known as the pituitary tumour transforming gene 1 (PTTG1), is a multifunctional protein that participates in mitosis, DNA repair, apoptosis and gene regulation13. Securin mediates tumorigenic mechanisms including cell transformation, aneuploidy and apoptosis13. Securin is highly expressed in human cancers and acts as a marker of invasiveness14. A recent study has shown that down regulation of securin in vitro and in vivo suppresses tumour growth and metastasis15. Our previous study showed that securin depletion induced senescence after irradiation and enhanced radiosensitivity in human cancer cells regardless of p53 expression8. However, the paracrine effect of radiation-induced senescence in securin-deficient cancer cells on neighbouring cells remains unclear.

In this study, we elucidated the molecular mechanism of radiation-induced senescence in human breast cancer cells with lower securin expression levels. In addition, we showed that radiation-induced senescent breast cancer cells released SASP factors to promote the migration, invasion and angiogenesis of neighbouring cells through both the IL-6/STAT3 and PDGF-BB/PDGFR signalling pathways. Our results provide the molecular mechanisms of radiation-induced senescence in securin-depleted cancer cells, including a SASP-induced paracrine effect.

Results

Radiation induced senescence in securin-deficient breast cancer cells through the ATM and p38 pathways

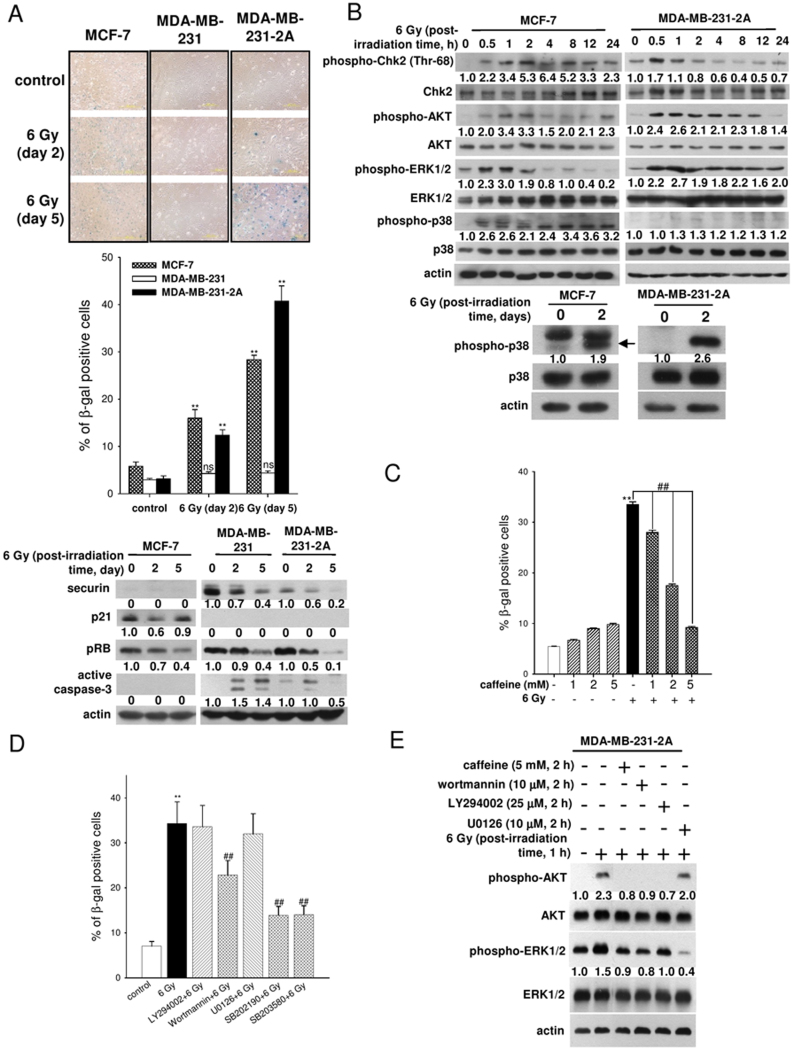

Western blot analysis was first used to confirm the securin protein levels in MCF-7 (low securin expression; p53 wild-type), MDA-MB-231 (high securin expression; p53-mutant) and securin-knockdown MDA-MB-231-2A (p53-mutant) human breast cancer cells (Fig. 1A, lower). Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining was performed to characterise radiation-induced senescence in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells (Fig. 1A, upper and middle), which correlated with the time-dependent reduction of pRB expression (Fig. 1A, lower). pRB downregulation was also observed in MDA-MB-231 cells that did not display a senescent phenotype (Fig. 1A, lower). In addition, p21 was not induced by radiation in these cells (Fig. 1A, lower). Moreover, radiation-induced apoptosis (as indicated by caspase-3 cleavage in Fig. 1A, lower, and Annexin V/Propidium Iodide double staining results in suppl. Fig. S1) in MDA-MB-231 cells was attenuated in securin-knockdown MDA-MB-231-2A cells. These results suggest that securin-deficient breast cancer cells were susceptible to radiation-induced senescence through RB- and p53/p21-independent pathways.

Figure 1. Radiation induced senescence in securin-deficient human breast cancer cells through the ATM and p38 MAPK pathways.

(A) Upper: MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-231-2A cells were exposed to 6 Gy radiation; then, SA-β-gal staining was performed 2 and 5 days after irradiation. Middle: the percentages of SA-β-gal-positive cells were quantified. Lower: the total cell extracts of MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-231-2A cells were prepared for western blot analysis. (B) Upper: MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells were treated with 6 Gy radiation followed by a 0–24-h recovery time. The levels of phospho-Chk2, -AKT, -ERK1/2, -p38, and total Chk2, AKT, ERK1/2, p38 were analysed through western blot analyses. Lower: MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells were treated with 6 Gy radiation followed by a 0–2-day recovery time. The levels of phospho-p38 and total p38 were analysed through western blot analyses. (C) MDA-MB-231-2A cells pretreated with or without the ATM/ATR inhibitor caffeine for 2 h were exposed to 6 Gy radiation; then, SA-β-gal staining was performed 5 days after irradiation. (D) MDA-MB-231-2A cells pretreated with or without a PI3K/AKT inhibitor (10 μM wortmannin or 25 μM LY294002), an ERK inhibitor (10 μM U0126) and p38 inhibitors (20 μM SB202190 and SB203580) for 2 h were exposed to 6 Gy radiation. Subsequently, SA-β-gal staining was performed 5 days after irradiation, and the percentages of SA-β-gal positive cells were quantified. (E) MDA-MB-231-2A cells pretreated with or without an ATM/ATR inhibitor (5 mM caffeine), a PI3K/AKT inhibitor (10 μM wortmannin and 25 μM LY294002) and an ERK1/2 inhibitor (10 μM U0126) for 2 h were exposed to 6 Gy radiation. Total cell extracts were prepared for Western blot analysis. A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between irradiated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.05 (#) and p < 0.01 (##) indicate significant differences between inhibitor-treated and untreated samples. Quantification of western blot bands was performed using densitometry and the proteins (A) or phospho-proteins/total protein (B, E); the ratio to actin is indicated.

To determine whether the DNA damage response was involved in radiation-induced senescence of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells, the levels of phospho-Chk2 (Th-68) were examined. The results showed that radiation elevated the levels of Chk2 phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). Treatment with caffeine (an ATM/ATR inhibitor) inhibited radiation-induced senescence in a dose-dependent manner in MDA-MB-231-2A cells (Fig. 1C). These findings suggest that the DNA damage response plays an important role in radiation-induced senescence in securin-deficient breast cancer cells.

To further investigate the molecular mechanism of radiation-induced senescence in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells, the activities of AKT, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK were examined through phosphorylation investigations. As shown in Fig. 1B, radiation increased the levels of phospho-AKT, -ERK1/2, and -p38. To determine the role of these signalling pathways, SA-β-gal staining was performed in the presence of inhibitors against PI3K/AKT (wortmannin and LY294002), MEK/ERK1/2 (U0126), and p38 (SB202190 and SB203580). SB202190 and SB203580 but not U0126 reduced radiation-induced senescence in MDA-MB-231-2A cells (Fig. 1D), indicating that p38 was a mediator of radiation-induced senescence. Interestingly, wortmannin but not LY294002 attenuated radiation-induced senescence even though both drugs inhibit AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 1D and 1E). Because wortmannin can also inhibit ATM16, its inhibitory effect on senescence might be a result of ATM inhibition.

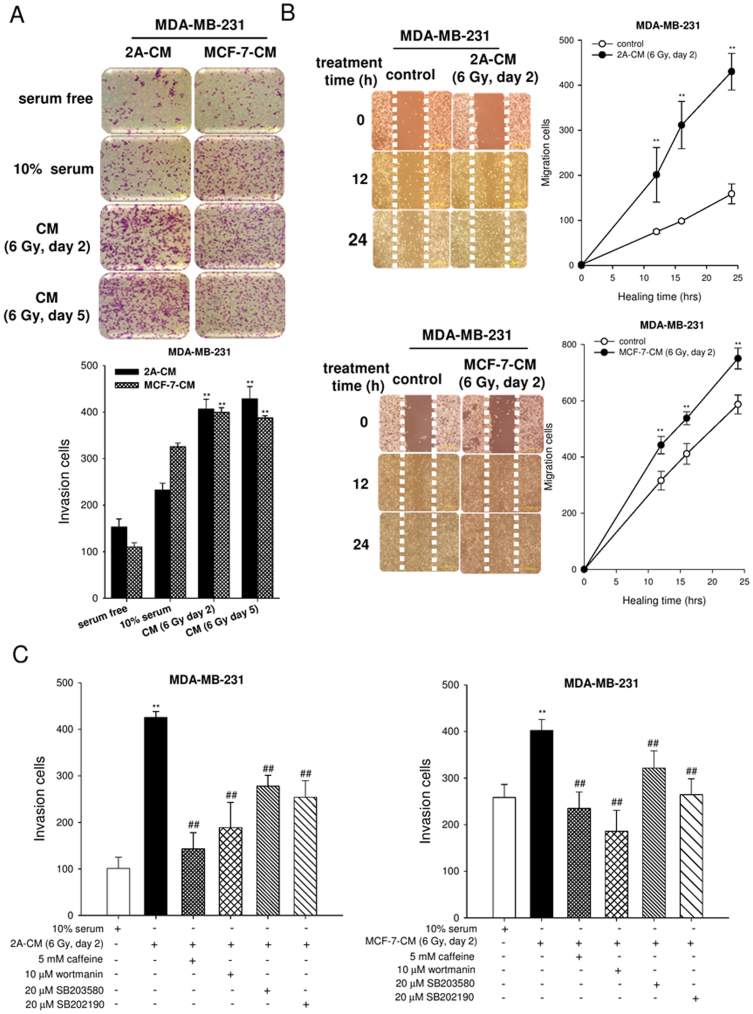

Radiation-induced SASPs promoted the migration and invasion of non-irradiated neighbouring cells

Recent evidence shows that cellular senescence is accompanied by the secretion of 40–80 SASP types1. To identify the radiation-induced SASPs, a cytokine array analysis was performed. As shown in suppl. Fig. S2, several proteins including cytokine IL-6, chemokine IL-8, IGFBP and GROα were secreted into conditioned medium (CM) of MDA-MB-231-2A cells (2A-CM). To verify whether these SASPs altered the behaviour of neighbouring cells, non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with the CM from irradiated MCF-7 (MCF-7-CM) and MDA-MB-231-2A (2A-CM) cells, and the levels of cell migration and invasion were examined using a wound-healing assay and a Boyden chamber assay, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2A and 2B, CM stimulated both invasion and migration of MDA-MB-231 cells. To investigate whether the blockage of radiation-induced senescence by inhibiting ATM and p38 pathways decreased the ability to promote invasion of neighbouring MDA-MB-231 cancer cells, the cells were incubated with CM from radiation-induced senescent MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells or with CM from cells pretreated with caffeine, wortmannin, SB203580 and SB202190 prior to irradiation. As shown in Fig. 2C, inhibition of the ATM and p38 pathways reduced the ability of irradiated MDA-MB-231-2A (left) and MCF-7 (right) cells to stimulate the invasiveness of non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells. These results show that radiation-induced senescent breast cancer cells have paracrine activity through secreting SASP factors to promote the migration and invasion of non-irradiated neighbouring cells.

Figure 2. The CM from radiation-induced senescent cells promoted the invasion and migration of non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells.

(A) Upper: MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with fresh medium, serum-free medium or CM for 16 h, and the collected filter membrane was stained with Giemsa. The effects of cell invasion were examined using a Boyden chamber assay. Lower: The numbers of invading cells were quantified. (B) A wound was produced on the cell layer with a pipette tip. The cells incubated with 2A-CM and MCF-7-CM were observed at the indicated time. Wound repair after 12–24 h of stimulation was observed under a microscope. The population of migrated cells was quantified. A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. (C) MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells were pretreated with or without an ATM/ATR inhibitor (caffeine 5 mM), a PI3K/AKT inhibitor (wortmannin 10 μM) and a p38MAPK inhibitor (SB203580, SB202190 20 μM) for 2 h were exposed to 6 Gy radiation. Subsequently, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 2A-CM or MCF-7-CM for 16 h, and the effects on cell invasion were examined using a Boyden chamber assay. The population of invading cells was quantified. A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.01 (##) indicates a significant difference in the CM from untreated and inhibitor-treated cells.

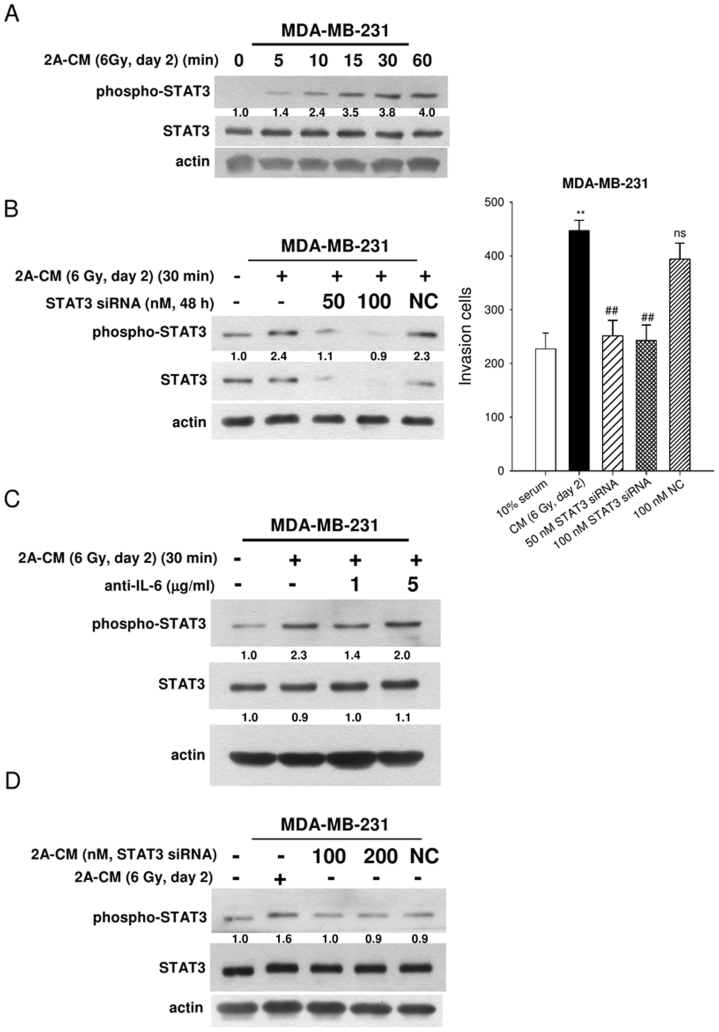

The IL-6/STAT3 signalling loop was required for the paracrine activity of senescent breast cancer cells

IL-6, a multifunctional cytokine that modulates cell survival and apoptosis, is upregulated in response to oncogene-induced senescence and is required for maintaining senescence in an autocrine manner17. A cytokine array analysis showed increased IL-6 release in radiation-induced senescent MDA-MB-231-2A cells (suppl. Fig. S2). The persistently high levels of IL-6 in 2A-CM were confirmed using an ELISA (Fig. 3A). Neutralisation using an IL-6 antibody reduced CM-induced migration and invasion of non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3B). The transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) has been shown to upregulate IL-6 gene expression, thereby accelerating tumour growth and metastasis18. Radiation activated STAT3 in MDA-MB-231-2A cells, as indicated by phosphorylation (Fig. 3C), which correlated with an increase in STAT3 transcriptional activity (Fig. 3D). STAT3 knockdown using siRNA or a dominant-negative mutant (DN) decreased radiation-induced STAT3 phosphorylation and IL-6 release (Fig. 3E and suppl. Fig. S3). Consistently, the CM from irradiated STAT3-knockdown MDA-MB-231-2A cells did not increase the invasion of non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3F). Therefore, the STAT3-dependent IL-6 release in 2A-CM promoted the invasion of non-irradiated neighbouring cells.

Figure 3. The effects of IL-6/STAT3 on cell invasion and migration.

(A) The levels of IL-6 in CM from MDA-MB-231-2A irradiated with 6 Gy followed by 0–120 h of recovery time were measured using an ELISA. (B) The effects of neutralisation of IL-6 antibody on CM-induced migration (left) and invasion (right) of non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells were examined using wound-healing and Boyden chamber assays, respectively. The numbers of invasive/migrated cells was quantified. A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.01 (##) indicates a significant difference between the group receiving CM alone and the CM + IL-6 Ab cells. (C) Western blot analysis was performed to determine the levels of phospho-STAT3 in MDA-MB-231-2A cells treated with radiation followed by 0–48 h recovery time. (D) The 4XM67TATA-Luc plasmid and the control SV-Luc plasmid were transfected into MDA-MB-231-2A cells. Then, the luciferase activity was measured after radiation. (E) Left: MDA-MB-231-2A cells were transfected with scrambled (NC) or STAT3 siRNA followed by radiation. The levels of phospho-STAT3 and STAT3 were ascertained by western blot analyses. Right: IL-6 secreted from cells transfected with STAT3 siRNA followed by radiation was measured using an ELISA. (F) Treatment was described in Figure 3E. The effects on MDA-MB-231 cell invasion were examined using a Boyden chamber assay. The population of invading cells was quantified. A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.01 (##) indicates a significant difference between CM from non-transfected and siRNA-transfected cells. Quantification of western blot bands was performed using densitometry, and the phospho-STAT3/STAT3 ratio to actin is indicated.

Because IL-6 is known to activate STAT319, we hypothesised that IL-6/STAT3 signalling acted as an autocrine or paracrine loop to promote cell invasion. Indeed, 2A-CM rapidly induced STAT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). To investigate the essential role of STAT3 in the invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells, endogenous STAT3 was knocked down using siRNA or a dominant-negative mutant (DN; Fig. 4B left, and suppl. Fig. S4A). As shown in Fig. 4B (right) and suppl. Fig. S4B, STAT3-knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells were resistant to 2A-CM-induced cell invasion. To exclude the possibility that factors other than IL-6 could activate STAT3, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 2A-CM neutralised by an anti-IL-6 antibody. As shown in Fig. 4C, the IL-6 antibody blocked 2A-CM-induced STAT3 phosphorylation. In addition, CM from senescent STAT3-knockdown MDA-MB-231-2A cells did not induce STAT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that the IL-6/STAT3 pathway may act as a signalling loop to maintain or amplify SASP effects.

Figure 4. The role of IL-6/STAT3 in 2A-CM-induced cell invasion.

(A) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 2A-CM for 0–60 min. The levels of phospho-STAT3 and total STAT3 were examined through western blot analyses. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with scrambled (NC) or STAT3 siRNA followed by 2A-CM treatment. The levels of phospho-STAT3 and total STAT3 in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 2A-CM were examined by western blot analyses (left). The effects of cell invasion were analysed using a Boyden chamber assay (right). The population of invading cells was quantified. A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.01 (##) indicates a significant difference between CM from non-transfected and siRNA-transfected cells. (C) The effects of neutralisation with an IL-6 antibody on levels of phospho-STAT3 in non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells were examined by western blot analyses. (D) MDA-MB-231-2A cells were transfected with scrambled (NC) or STAT3 siRNA followed by radiation. The MDA-MB-231 cells were treated by 2A-CM from non-transfected and siRNA-transfected cells. The levels of phospho-STAT3 were examined by western blot analysis. Quantification of western blot bands was performed using densitometry, and the phospho-STAT3/STAT3 ratio to actin is indicated. In (C), the STAT3/actin ratio is also indicated.

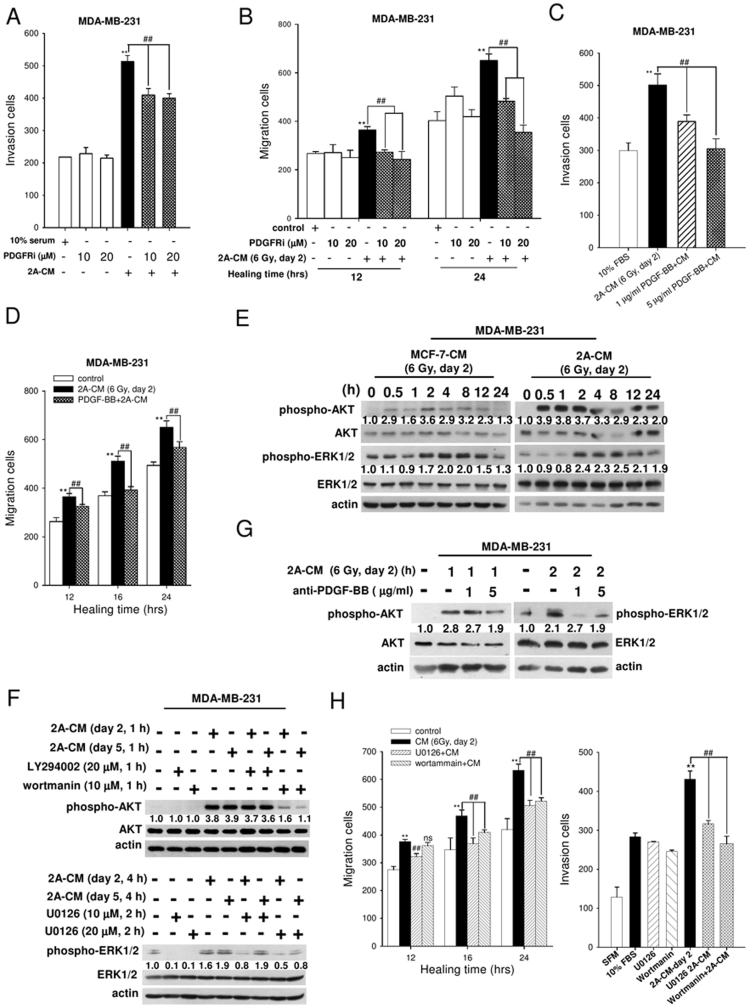

PDGF/PDGFR signalling acted as a mediator between SASPs and non-irradiated neighbouring cells

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) secreted by senescent cells is a growth factor that regulates cell growth and division of pericytes, which cover endothelial cell channels to provide stability and control perfusion of blood vessels20. The PDGFR (α and β) is a trans-membrane receptor tyrosine kinase activated by PDGF. Once activated, tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor activates a number of downstream signalling pathways, including PI3K/AKT, ERK1/2, PLC/PKC, and STAT, which are involved in cell growth and survival, transformation, migration, vascular permeability, stroma modulation and wound healing21,22. A cytokine array analysis showed an increased release of the PDGFR ligand PDGF-BB in the CM of radiation-induced senescent MDA-MB-231-2A cells (suppl. Fig. S2). To investigate whether PDGFR promotes the invasion of neighbouring cells, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with a PDGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor III and incubated with 2A-CM. As shown in Fig. 5A and 5B, the PDGFR inhibitor attenuated CM-induced cell invasion and migration. To confirm the role of the PDGF/PDGFR pathway, the PDGF-BB in 2A-CM was neutralised with an antibody. As shown in Fig. 5C and 5D, the anti-PDGF-BB antibody reduced the CM-induced invasion and migration of MDA-MB-231 cells.

Figure 5. The effects of PDGF-BB/PDGFR signalling on cell invasion and migration.

(A) MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-treated with a PDGFR inhibitor for 1 h and cultured with 2A-CM for 16 h. The effects of cell invasion were examined using a Boyden chamber assay. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-treated with a PDGFR inhibitor for 1 h and incubated with 2A-CM for 0–24 h. The effects on cell migration were examined through a wound-healing assay. For (A) and (B), A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.01 (##) indicates a significant difference between CM from untreated and inhibitor-treated cells. (C) and (D) The effects of neutralisation of a PDGF-BB antibody on CM-induced invasion and migration of non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells were examined using Boyden chamber and wound-healing assays, respectively. The numbers of invading/migrated cells was quantified. A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.01 (##) indicates a significant difference between cells treated with CM alone and PDGF-BB Ab +CM. (E) The levels of phospho-AKT, -ERK1/2, total AKT and ERK1/2 in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with CM from irradiated MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells were analysed through western blot analyses. (F) MDA-MB-231 cells were pretreated with U0126, LY294002 and wortmannin followed by 2A-CM treatment. The levels of active AKT and ERK1/2 were ascertained through western blot analyses. (G) The effects of neutralisation of a PDGF-BB antibody on levels of phospho-AKT and -ERK1/2 in non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells were examined through western blot analyses. (H) MDA-MB-231 cells were pretreated with 20 μM U0126, 20 μM LY294002 and 10 μM wortmannin for 2 h followed by 2A-CM treatments. The numbers of migratory (left) and invading (right) cells were examined using Boyden chamber and wound-healing assays, respectively. A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.01 (##) indicates a significant difference between cells with and without inhibitor pretreatments. Quantification of western blot bands was performed using densitometry, and the phospho-proteins/total protein ratio to actin is indicated.

Both the PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 pathways act as signalling proteins downstream of PDGFR21,22. Our results showed that the CM activated AKT and ERK1/2, as indicated by their phosphorylation in non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5E). Wortmannin but not LY294002 blocked AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 5F, upper), indicating that 2A-CM-induced AKT activation was dependent on ATM but not PI3K. U0126 inhibited 2A-CM-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 5F, lower), confirming the activation of ERK signalling. Neutralisation of PDGF-BB using an antibody reduced the levels of phospho-AKT and -ERK1/2 induced by 2A-CM in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5G). In addition, wortmannin and U0126 reduced 2A-CM-induced migration and invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5H). These results suggest that PDGF-BB/PDGFR signalling acts as a mediator to induce AKT and ERK1/2 pathway activation and promote the invasion and migration of neighbouring cells.

SASPs induced angiogenesis involving the IL-6R/STAT3 and PDGF-BB/PDGFR pathways

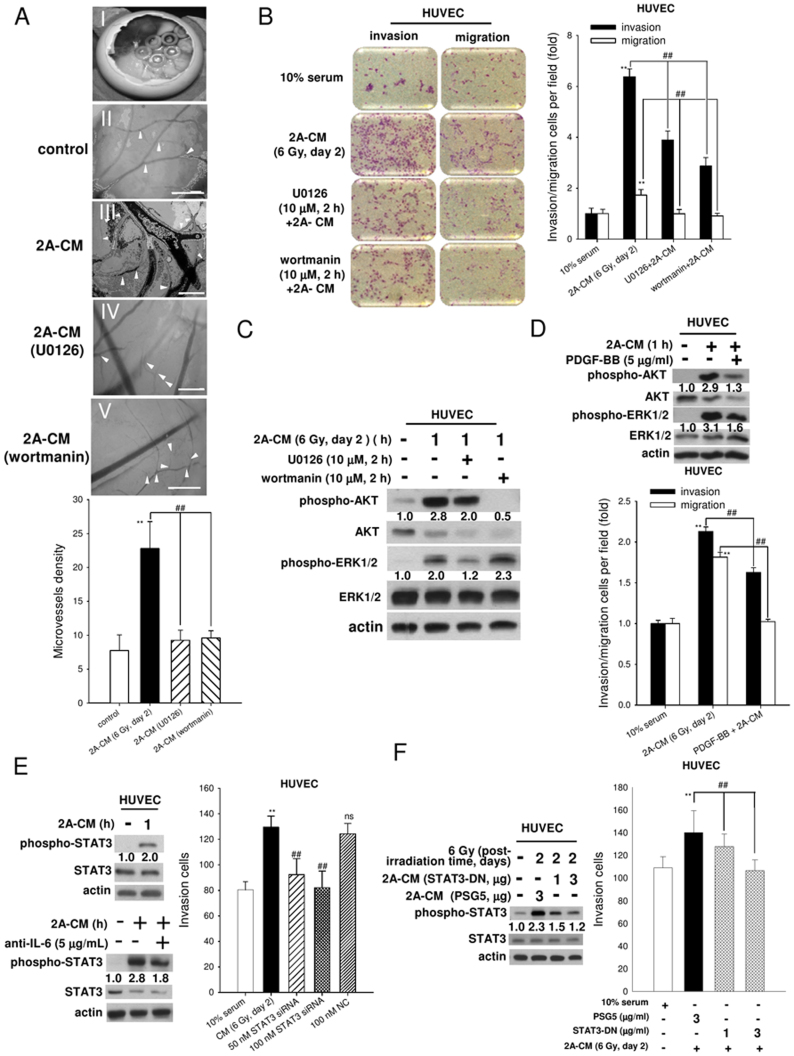

It has been reported that the CM from senescent fibroblasts stimulate angiogenesis9. To investigate whether the CM from senescent MDA-MB-231-2A breast cancer cells also promote angiogenesis, the chicken CAM assay was performed (Fig. 6A-I). 2A-CM induced angiogenesis compared with the control medium (Fig. 6A-II and -III). U0126 and wortmannin inhibited CM-induced angiogenesis (Fig. 6A-IV and -V), indicating that SASPs induced angiogenesis through the AKT and ERK1/2 pathways. It has been reported that endothelial cells play an important role in angiogenesis23. To investigate whether SASPs in CM increase the invasive and migratory ability of endothelial cells, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were incubated with 2A-CM. As shown in Fig. 6B, 2A-CM significantly stimulated HUVEC invasion and migration. Consistently, wortmannin and U0126 inhibited HUVEC invasion and migration. In addition, both AKT and ERK1/2 were activated by 2A-CM in HUVECs, which were inhibited by wortmannin and U0126, respectively (Fig. 6C). These results indicated that the PDGF-BB/PDGFR pathway may mediate SASP-induced angiogenesis. Indeed, neutralisation of PDGF-BB with an antibody reduced 2A-CM-induced activation of AKT and ERK1/2 and HUVEC invasion and migration (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. CM induced angiogenesis in chicken chorioallantoic membrane and HUVEC invasion through the IL-6/STAT3 and PDGF-BB/PDGFR pathways.

(A) The observation window was opened on fertilised chicken eggs at day 2 of incubation (A-I). Microvessels (arrow head) were observed under a dissecting scope on chicken embryos treated with control medium and 2A-CM from cells pretreated without or with inhibitors (wortmannin and U0126, 10 μM) (A-II to -V). (B–F) HUVECs were pretreated with inhibitors, U0126 and wortmannin and incubated with 2A-CM. In (B), the effects of cell invasion and migration were examined using a Boyden chamber assay with coated and non-coated membranes, respectively. In (C), the levels of phospho-AKT, total AKT, phospho-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 were analysed by western blot analysis. In (D), the effects of neutralisation of a PDGF-BB antibody on levels of phospho-AKT and -ERK1/2 in HUVECs were examined by western blot analysis (upper part), and the levels of cell invasion and migration were examined using the Boyden chamber assay (lower). In (E), the effects of neutralisation of IL-6 antibody on levels of phospho-STAT3 in HUVECs were examined by western blot analysis (left and lower). Right: MDA-MB-231-2A cells were transfected with scrambled or STAT3 siRNA followed by irradiation. The effects on HUVEC invasion were examined using a Boyden chamber assay. In (F), the levels of phospho-STAT3 in HUVECs treated with CM from MDA-MB-231-2A cells transfected with STAT3-DN followed by irradiation were determined through western blot analyses (left). The effects of cell invasion were examined using a Boyden chamber assay (right). A p value of <0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between CM-treated and untreated samples. A p value of <0.01 (##) indicates a significant difference between cells treated with CM alone and pretreated with inhibitors (U0126 and wortmannin), neutralised PDGF-BB antibody, STAT3 siRNA, or STAT3-DN. Quantification of western blot bands was performed using densitometry, and the phospho-proteins/total protein ratio to actin is indicated.

We further investigated whether the IL-6/STAT3 pathway was involved in SASP-induced HUVEC invasion. As shown in Fig. 6E (left upper and lower), STAT3 activation was induced by 2A-CM in HUVECs, which was attenuated by neutralisation with an IL-6 antibody. In addition, CM from irradiated STAT3-knockdown MDA-MB-231-2A cells lost the ability to stimulate HUVEC invasion (Fig. 6E, right). Consistently, the CM from irradiated MDA-MB-231-2A cells transfected with STAT3-dominant-negative (DN) plasmids did not activate STAT3 or promote HUVEC invasion (Fig. 6F). Therefore, we propose that SASPs induce angiogenesis through the PDGF-BB/PDGFR and IL-6/STAT3 signalling pathways.

Discussion

Senescence is a metabolically active form of irreversible growth arrest that halts the proliferation of damaged cells. It is considered a tumour suppressive program. However, there is increasing evidence suggesting that senescence is also associated with the disruption of the tissue microenvironment and development of a pro-oncogenic environment, principally via SASP secretion24. We found that radiation induced senescence in breast cancer cells with low securin expression; these cells in turn released SASPs to promote the migration and invasion of neighbouring cancer cells.

Securin correlates with a poor prognosis in multiple tumour types including breast tumors25. Securin loss has been reported to sensitise cancer cells to various anticancer agents26, and securin downregulation by a full-length antisense mRNA, antisense oligonucleotides, and siRNA inhibits cell proliferation and tumour formation in several cancers27,28,29. However, the role of securin in senescence is still controversial. Securin overexpression induces senescence in normal fibroblasts but attenuates anticancer drug-induced senescence in human colon cancer cells30,31. Our previous and current studies showed that radiation induced senescence in securin-depleted breast and colon cancer cells8, indicating that securin is a negative regulator of senescence in cancer cells. Thus, it is possible that securin plays an opposite role in normal and cancer cells. Ionising radiation is known to induce senescence in both normal and cancer cells. Our present findings showed that radiation-induced senescence in both MCF-7 human breast cancer cells with low expression of securin and securin-knockdown MDA-MB-231-2A cells promoted the invasion and migration of the neighbouring cells.

The hallmark of senescent cells is irreversible p53/p21- or p16INK4a/pRb-dependent cell cycle arrest. Thus, loss of p53 or p16INK4a pathway may disrupt the senescence response in cancer cells32. However, our previous study showed that securin depletion induces senescence after irradiation in human cancer cells regardless of functional p53 expression8. In this study, we also found that neither the p53/p21- nor the p16INK4a/pRb pathways were required for radiation-induced senescence in human breast cancer cells. Consistently, it has been reported that downregulation of p300 histone acetyltransferase activity induces senescence independent of the p53 and p16INK4a pathway33. Thus, other mechanisms may contribute to stress-induced senescence. Our results indicated that the ATM and p38 pathways were required for radiation-induced senescence in human breast cancer cells with low securin expression.

After radiation, the DNA damage response (ATM/Chk2) is activated immediately, whereas the SASPs develop slowly over several days, suggesting that there are other, slower events that facilitate SASP release34. We found that both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A human breast cancer cells activated Chk2 and AKT early and transiently after irradiation; however, p38 MAPK was activated more slowly. Several studies have indicated that p38 MAPK inhibition during DNA damage-induced senescence reduces the expression of SASPs such as IL-6 and IL-8 that may contribute to cancer cell metastasis35,36. In contrast, a recent report showed that p38 MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of SASPs36. Our present study showed that inhibition of both the AKT and p38 MAPK pathways decreased CM-induced invasion of neighbouring MDA-MB-231 cells, which might be due to the reduction of SASP secretion. Taken together, we suggest that p38 MAPK activation, with slow and chronic kinetics, is involved in radiation-induced senescence in both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells and consequently promotes the invasion and migration of cancer cells through SASP secretion.

Twelve proteins were upregulated in the CM from radiation-induced senescent MDA-MB-231-2A cells (Suppl. Fig. S2). We have demonstrated that both the IL-6/STAT3 and the PDGF-BB signalling pathways were essential for SASP-induced cell migration and invasion. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other SASPs also act to promote these autocrine and paracrine phenomena after irradiation. For example, it has been shown that expression of IGFBP, which acts as regulator of senescence/immortalisation, is increased in senescent cells37. This result suggests that the SASPs secreted from radiation-induced senescent MDA-MB-231-2A cells play a functional role to initiate and maintain cellular senescence. Other SASPs such as MIP-3α, GM-CSF and MCP-1, which are secreted from senescent cells, stimulate the innate immune system and may eliminate senescent cells10. Both the chemokine IL-8 and GROα have also been described as having pro-tumourigenic functions12. Therefore, we suggest that the SASPs secreted from radiation-induced senescent MDA-MB-231-2A human breast cancer cells maintain senescence and promote the invasion of neighbouring cells through autocrine and paracrine activities, respectively. Further investigations are needed to confirm their roles.

A recent report has demonstrated that STAT3-induced tumorigenesis is mediated by IL-6 signalling auto-regulation17. In this study, we showed that radiation induced senescence and STAT3 activation in MDA-MB-231-2A human breast cancer cells and subsequently promoted IL-6 secretion into the CM in a post-irradiation time-dependent manner, suggesting that STAT3 activation contributes to IL-6 secretion through autocrine activity. As shown in our results, dominant-negative transfection and knockdown of STAT3 in MDA-MB-231-2A cells reduced the invasion of non-irradiated MDA-MB-231 and HUVECs induced by the CM from radiation-induced senescent MDA-MB-231-2A cells. Therefore, we suggest that IL-6/STAT3 promotes the invasion of neighbouring cells through paracrine activity.

Emerging evidence has revealed that the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) due to the migration of endothelial cells in the tumour microenvironment increases cancer cell metastasis through trans-endothelial invasion20,38,39. In this study, we found that the CM from radiation-induced senescent MDA-MB-231-2A cells promoted HUVEC invasion and angiogenesis in chicken chorioallantoic membrane through activation of the ATM/AKT and ERK1/2 pathways. Because HUVECs are isolated from normal human umbilical veins and angiogenesis occurs in microvessels (capillaries), using capillary-derived endothelial cells might provide more physiologically relevant results. However, it has been demonstrated that HUVECs maintain the phenotype of endothelial cells in vivo, including angiogenesis40. In addition, we showed that the microvessels in chicken chorioallantoic membrane were reduced by ATM/AKT and ERK1/2 inhibitors. Thus, by combining the inhibition of ATM/AKT and ERK1/2 during radiotherapy, breast cancer metastasis after irradiation might be inhibited through the reduction of angiogenesis.

In conclusion, we suggest that radiation-induced senescence in MCF-7 (low expression of securin) and MDA-MB-231-2A (securin-knockdown) cancer cells is p53/p21- and p16INK4a/pRb-independent but securin dependent. Furthermore, in both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells, the ATM and p38 pathways were involved in radiation-induced senescence. Secretion of SASPs from radiation-induced senescent MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231-2A cells promoted the invasion and migration of neighbouring cells through the activation of various signalling pathways. Among the released SASPs, PDGF-BB activated PDGFR signalling, which activated ATM/AKT and ERK1/2 pathways. Furthermore, IL-6 was induced by radiation through STAT3 in the breast cancer cells with low securin expression, which can then activate IL-6/STAT3 signalling in neighbouring cells.

Methods

Chemicals and antibodies

Propidium iodide (PI) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO). U0126, LY294002, wortmannin, SB202190, SB203580 and PDGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor III were purchased from Merck Calbiochem (San Diego, MA). N-acetyl-L-cysteine and caffeine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The anti-PDGF-BB and anti-IL-6 antibodies were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The anti-phospho-Chk2 (Th-68), Chk2, Rb (4H1), anti-phospho-p38, anti-phospho-AKT (Ser-473), anti-AKT, anti-phospho-ERK1/2, anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr-705) and anti-STAT3 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). The monoclonal anti-securin antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridgeshire, UK). The anti-actin antibody was purchased from Chemicon International (California, USA). The anti-p21Cip1/WAF1 (Ab-1) mouse mAb (EA10) antibody was purchased from Merck Calbiochem. Anti-p38 and anti-ERK1/2 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-caspase-3 was purchased from Imgenex (San Diego, CA).

Cell culture

The MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell lines, kindly provided by Dr. Ji-Hshiung Chen (Department of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Tzu Chiu University, Taiwan)8, were grown in DMEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 1 mM sodium pyruvate solution. The human securin small hairpin RNA securin-knockdown MDA-MB-231-2A cells were kindly provided by Dr. Ji-Hshiung Chen (Department of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Tzu Chi University)8 and selected using DMEM containing 0.5 μg/ml puromycin dihydrochloride. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), purchased from Sciencell Research Laboratories, were grown in endothelial cell medium (ECM) supplemented with 5% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator and passaged every 2 days (310/Thermo, Forma Scientific, Inc., Marietta, OH).

X-ray irradiation

Radiation was generated using an X-ray machine (RS2000; RAD Source Technologies) operating at 160 kVp (peak kilovoltage) and 25 mA, as described previously8. The cells were replenished with fresh medium and immediately subjected to X-ray irradiation. A 6-Gy radiation dosage was chosen for this study according to our previous finding that senescence was induced by 3–6 Gy irradiation8.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining

Senescent cells were analysed using a β-gal staining kit (Cell Signaling) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells was then calculated as described previously8.

Western blot analysis

Preparation of cellular protein extracts and procedures for western blot analysis were described in our previous studies8,41.

Conditioned media and ELISA

To generate the senescent conditioned media (CM), MDA-MB-231-2A cells were grown in DMEM for 24 h with or without inhibitors followed by irradiation. After a post-irradiation period of 2 or 5 days, the media were collected and centrifuged at 2000 × g for 5 min at 4°C to remove the cell debris or filtered through a 0.22-μm filter (Millipore); then, the CM were stored at −80°C. An ELISA kit from R&D Systems was used to detect IL-6 (D6050) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Luciferase reporter assay

MDA-MB-231-2A cells were transfected with 100 ng of pCEP4-SV40-luc or pTATA-TK-luc 4XM67 using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche) following the manufacturer's protocol. The transfected cells were exposed to irradiation 4 and 8 h before the luciferase activity assay was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega) using Sirius luminometer (Berthold Detection System). The STAT3-dependent luciferase activity or control pCEP4-SV40-luc were calculated by the resulting activity of each transfectant expressed relative to the background level obtained from the control group.

Boyden chamber analysis

An invasion assay was performed using gelatin (Sigma)-coated membranes (pore size, 8 μm; BD Biosciences). The membrane was soaked in 0.5 M acetic acid for 24 h to allow for pore enlargement; subsequently, the membrane was rinsed twice with double deionised water (ddH2O) before being soaked in 100 μg/mL gelatin for 16 h. Approximately 8 × 103 cells were suspended in 1% (MDA-MB-231) and 5% (HUVECs) serum medium and plated in the top chamber (Neuro Probe, Inc.). Medium supplemented with 10% serum DMEM or senescent CM was used as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber. After incubation for 16 h, the cells remaining on the bottom side of the membrane were stained with Giemsa (Merck), imaged and counted.

Wound-healing assay

The cells were cultured at a density of 8 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates for 24 h, resulting in a monolayer more than 90% confluent. The monolayer cells were scraped with a 200-μl pipette tip to generate a wound and treated with control medium or CM for various periods. Images were collected after 4–36 h of the same wound position. The wound area was determined by outlining the wound, and the migrated cells in the wound area were calculated manually.

Antibody arrays

CM and control medium were analysed using antibody arrays kit (RayBio™ Human Cytokine Antibody Array 5 Map) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Signal intensities were quantified using the gel-digitising software Un-Scan-It gel (ver. 5.1; Silk Scientific, Inc., Orem, UT) and normalised to the positive control for each sample, which were then normalised across all samples.

STAT3 siRNA knockdown and overexpression of a STAT3 dominant-negative plasmid

STAT3 small interfering RNA (siRNA) ([5′/3′] sense: AAG AUA CCU GCU CUG AAG AAA CUG C; antisense: GCA GUU UCU UCA GAG CAG GUA UCU U; VHS40491) and scrambled siRNA (12935-100) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). MDA-MB-231-2A cells were transfected with the above siRNA oligonucleotides using X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with 1 μg/ml and 3 μg/ml of PSG5 vector or pEF-STAT3 dominant-negative plasmid using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche). After transfection, the cells were subjected to irradiation or western blot analysis as described above.

The chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay

Chicken embryos were purchased from Animal Health Research Institute (Taiwan, R.O.C.). Briefly, 10-day-old chick embryos were removed from the shells. Sterilised silicone O-rings were placed on the chicken CAM surfaces above the dense subectodermal plexus, and 20 μl of concentrated CM was concentrated tenfold using spin-X UF centrifugal concentrators (Corning, USA) and then added in the middle of the O-ring and incubated at 37°C. After 48 h, angiogenesis of the chicken embryos was examined under a dissecting scope and photographed. At the end of the experiment, the embryos were sacrificed by opening their air sacs.

Statistical analyses

All data are represented by the mean ± standard error of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance, and further post hoc testing was performed using the statistical software GraphPad Prism 4 (Graph-Pad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA). A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Author Contributions

Y.-C. performed the majority of experiments and data analysis. P.-M. participates in data analysis and drafted the manuscript. Q.-Y. and Y.-H. performed the chicken chorioallantoic membrane assay. C.-W. carried out the Luciferase Reporter assay. Y.-J. participates in data analysis. S.-J. conceived and designed experiments, as well as coordinated and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 99-2314-B-320-004-MY3).

References

- Ren J. L., Pan J. S., Lu Y. P., Sun P. & Han J. Inflammatory signaling and cellular senescence. Cell. Signal. 21, 378–383 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora E., Arendt T., Bennett M. & Narita M. Impact of cellular senescence signature on ageing research. Ageing Res. Rev. 10, 146–152 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado M. & Serrano M. The power and the promise of oncogene-induced senescence markers. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 472–476 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. & d'Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 729–740 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le O. N. et al. Ionizing radiation-induced long-term expression of senescence markers in mice is independent of p53 and immune status. Aging Cell 9, 398–409 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliouat-Denis C. M. et al. p53-independent regulation of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression and senescence by Chk2. Mol. Cancer Res. 3, 627–634 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solbach C., Roller M., Eckerdt F., Peters S. & Knecht R. Pituitary tumor-transforming gene expression is a prognostic marker for tumor recurrence in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. BMC Cancer 6, 242 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. S. et al. Depletion of securin induces senescence after irradiation and enhances radiosensitivity in human cancer cells regardless of functional p53 expression. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 77, 566–574 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppe J. P., Desprez P. Y., Krtolica A. & Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 5, 99–118 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier F. & Campisi J. Four faces of cellular senescence. J. Cell Biol. 192, 547–556 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A., Kauppinen A. & Kaarniranta K. Emerging role of NF-kappaB signaling in the induction of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Cell. Signal. 24, 835–845 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuilman T. & Peeper D. S. Senescence-messaging secretome: SMS-ing cellular stress. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 81–94 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlotides G., Eigler T. & Melmed S. Pituitary tumor-transforming gene: physiology and implications for tumorigenesis. Endocr. Rev. 28, 165–186 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S. et al. PTTG overexpression promotes lymph node metastasis in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 69, 3283–3290 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panguluri S. K., Yeakel C. & Kakar S. S. PTTG: an important target gene for ovarian cancer therapy. J. Ovarian Res. 1, 6 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkaria J. N. et al. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase related kinases by the radiosensitizing agent wortmannin. Cancer Res. 58, 4375–4382 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. L. et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation up-regulates interleukin-6 autocrine production: a biochemical and genetic study of established cancer cell lines and clinical isolated human cancer cells. Mol. Cancer 9, 309 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. Regulation of metastases by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling pathway: clinical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 1362–1366 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Kortylewski M. & Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 41–51 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. & Jain R. K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473, 298–307 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matei D. et al. PDGF BB induces VEGF secretion in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 6, 1951–1959 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson L. E. & Soriano P. PDGFRbeta signaling regulates mural cell plasticity and inhibits fat development. Dev. Cell 20, 815–826 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W. et al. 5-Formylhonokiol exerts anti-angiogenesis activity via inactivating the ERK signaling pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 43, 146–152 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin R. J. & Anderson R. M. Cellular Senescence - its role in cancer and the response to ionizing radiation. Genome Integr. 2, 7 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbagabriel S., Fernando M., Waldman F. M., Bose S. & Heaney A. P. Securin is overexpressed in breast cancer. Mod. Pathol. 18, 985–990 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney A. P. et al. Expression of pituitary-tumour transforming gene in colorectal tumours. Lancet 355, 716–719 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakar S. S. & Malik M. T. Suppression of lung cancer with siRNA targeting PTTG. Int. J. Oncol. 29, 387–395 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. et al. Inhibitory effects of anti-sense PTTG on malignant phenotype of human ovarian carcinoma cell line SK-OV-3. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog. Med. Sci. 24, 369–372 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solbach C. et al. Pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG): a novel target for anti-tumor therapy. Anticancer Res. 25, 121–125 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y., Zhao W., Zhou C., Wawrowsky K. & Melmed S. PTTG1 attenuates drug-induced cellular senescence. PLoS ONE 6, e23754 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y. H. et al. Overexpression of the pituitary tumor transforming gene induces p53-dependent senescence through activating DNA damage response pathway in normal human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22630–22638 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beausejour C. M. et al. Reversal of human cellular senescence: roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. EMBO J. 22, 4212–4222 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieur A., Besnard E., Babled A. & Lemaitre J. M. p53 and p16(INK4A) independent induction of senescence by chromatin-dependent alteration of S-phase progression. Nat. Commun. 2, 473 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund A., Orjalo A. V., Desprez P. Y. & Campisi J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 238–246 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene G. F. et al. Correlation of metastasis-related gene expression with metastatic potential in human prostate carcinoma cells implanted in nude mice using an in situ messenger RNA hybridization technique. Am. J. Pathol. 150, 1571–1582 (1997). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund A., Patil C. K. & Campisi J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J. 30, 1536–1548 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Cellular senescence as a tumor-suppressor mechanism. Trends Cell Biol. 11, S27–31 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valastyan S. & Weinberg R. A. Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell 147, 275–292 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. & Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. et al. In vitro angiogenesis by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) induced by three-dimensional co-culture with glioblastoma cells. J. Neurooncol. 92, 121–128 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S. J., Chao J. I., Lee Y. J. & Hsu T. S. Regulation of gamma-H2AX and securin contribute to apoptosis by oxaliplatin via a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. Toxicol. Lett. 179, 63–70 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information