Abstract

In cardiac muscle cells, ryanodine receptor (RyR) mediated Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) drives the contractile apparatus. Spontaneous bouts of inter-RyR Ca2+ induced Ca2+ release (CICR) generate an elemental unit of SR Ca2+ release called a spark. Sparks are localized events that terminate soon after they begin. The local control of sparks is not clearly understood. In this article, we review the potential regulatory role that the changing single RyR Ca2+ current may play. Moreover, we aggregate RyR data into a working scheme of inter-RyR CICR current control of sparks and a potential inter-RyR CICR termination mechanism that we call pernicious attrition.

In cardiac muscle, the action potential activates dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) Ca2+ channels across the surface membrane and transverse tubule membrane. Each DHPR mediates a small Ca2+ influx that activates underlying cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) Ca2+ release channels on the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Each open RyR2 mediates a relatively large Ca2+ flux into the cytosol. This DHPR-RyR2 Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) initiates cardiac excitation-contraction coupling (ECC). RyR2s are clustered at discrete SR release sites and just some are associated with DHPRs. Non-DHPR linked RyR2s are activated via inter-RyR2 CICR. The result is the large cytosolic Ca2+ transient that drives the contractile apparatus.

During diastole, RyR2 channels are predominantly closed. There is, however, always some probability that a RyR2 will spontaneously open. When one does, it mediates a Ca2+ flux into the cytosol and this Ca2+ can trigger inter-RyR2 CICR at that release site, generating a Ca2+ spark [1]. If not, the Ca2+ released represents non-spark RyR-mediated SR Ca2+ leak [2,3]. The cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by a typical spark is usually insufficient to activate RyR2s at neighboring release sites and thus sparks are local spatially-confined events. Abnormally large (or frequent sparks) can activate RyR2s at neighboring release sites, generating propagating SR Ca2+ waves that travel across the cells during diastole [4].

Sparks are thought to be normal events in cardiac muscle cells that contribute to the normal SR Ca2+ leak and consequently govern overall SR Ca2+ load [5]. Spontaneous Ca2+ waves are abnormal events. During a wave, some of the released Ca2+ will be extruded from the cell via Na-Ca2+ exchange (NCX) activity. Since NCX function is electrogenic, this may depolarize a cell during diastole sufficiently to trigger an action potential and possibly initiate a life-threatening arrhythmia. Despite decades of effort, the mechanisms that control the inter-RyR2 CICR underlying sparks and waves remain poorly understood. For example, the local negative control that counters the inherent positive feedback CICR is unknown. Also, we know that sparks are critically controlled by local intra-SR (luminal) Ca2+ levels but exactly how is unclear. Here, we describe the role of the single RyR2 Ca2+ current in CICR local control and its possible contribution to the luminal Ca2+ sensitivity and termination of sparks.

This review briefly describes how the luminal Ca2+ sensitivity of local SR Ca2+ release may rise in mammalian cardiac muscle. It describes the changes in single RyR2 Ca2+ current amplitude that naturally occur during a spark as well as the local cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by a single RyR2 opening event. The potential role of this signal in modulating local RyR2 activity is discussed and we coin the term pernicious attrition to describe the failure of local inter-RyR2 CICR as the signal becomes smaller. An attempt was made to present this growing complex body of information in a readable easily-understood way. It was impractical to describe and include all the quality studies that comprise this field but we hope this effort helps general interest readers understand local CICR control in heart better.

Luminal Ca2+ Sensitivity

Spark frequency increase dramatically as SR Ca2+ load rises [6] and sparks terminate when the local SR load (intra-SR free Ca2+ level) falls to a critical level [7-9], the termination threshold. It is thought that single RyR2 channels somehow “sense” changes in local SR load. This intra-SR Ca2+ sensing may arise from Ca2+ binding to the luminal side of the RyR2 protein itself or to an intra-SR protein that is closely associated with the RyR2 [10]. The most popular RyR2 luminal Ca2+ sensing mechanism involves the calsequestrin (CASQ), triadin (TD) and junctin (JN) proteins [11-14]. Indeed, there are naturally occurring RyR2, CASQ and TD mutations [15-19] linked to catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), a form of wave-evoked arrhythmia associated with abnormal RyR2 luminal Ca2+ sensitivity. It is commonly believed that intra-SR Ca2+ sensing mechanisms entirely explained the luminal Ca2+ sensitivity of SR Ca2+ sparks. There is, however, another way that local SR Ca2+ load may control local Ca2+ release.

The local SR Ca2+ load defines the magnitude of the trans-SR Ca2+ driving force. Thus, local load determines the single RyR2 Ca2+ current amplitude. The single RyR2 Ca2+ current provides the local Ca2+ signal that drives the inter-RyR2 CICR underlying the spark. As SR load rises, this local Ca2+ signal will become larger because the current is bigger. The larger local Ca2+ signal intuitively will increase the likelihood of inter-RyR2 CICR (i.e. sparks). As load falls, the local Ca2+ signal will become smaller and the likelihood that inter-RyR2 CICR starts (or continues) becomes less. The possible contribution of single RyR2 Ca2+ current in CICR local control is an embedded element, typically not emphasized, in several modeling studies [20-24]. Recently, Sato & Bers [24] have even described current control of sparks with impressive quantitative detail and current control seems to be gaining in popularity as a potentially significant load-dependent process that helps govern sparks and waves [8,9,25,26]. Until recently, this current control scenario has been experimentally difficult to verify because single RyR2 Ca2+ current and local SR load are difficult to differentially manipulate in cells. We recently overcame this obstacle and experimentally showed that single RyR2 Ca2+ current amplitude does indeed substantially contribute to spark local control [27].Thus, RyR2 luminal Ca2+ controls of sparks and waves is very likely due to a composite of processes that include intra-SR Ca2+ sensing mechanisms and single RyR2 current control of inter-RyR2 CICR.

The Single RyR2 Ca2+ Current

Single RyR2 function has been defined by incorporating the channel into planar lipid bilayers[10]. The RyR2 is a poorly selective Ca2+ channel [28] and multiple RyR2-permeable cations (K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+) are present in cells. There are normally no trans SR K+ or Mg2+ gradients and the high SR K+ permeability holds the SR at 0 mV [29], the K+ equilibrium potential. When the RyR2 opens, all RyR2-permeable ions enter the poorly selective pore. There is a net SR Ca2+ efflux (at 0 mV) because there is a trans-SR Ca2+ gradient. Without K and Mg present, the single RyR2 Ca2+ current (at 0 mV) can be as large as ~4 pA when super-physiological luminal Ca2+ levels (e.g. 10-50 mM) are present [30]. In cell-like salt solutions (i.e. 120 mM K, 1 mM free Mg and <100 μM free Ca2+ in the cytosol; 120 mM K, 1 mM free Mg and 1 mM free Ca2+ in the SR lumen), single RyR2 channel Ca2+ current amplitude at 0 mV is ~0.35 pA [27,31-33]. Since robust SR countercurrent assures that the SR Vm never strays far from 0 mV [29,33,34], the amplitude of the single RyR2 channel Ca2+ current is likely near 0.35 pA in cells if local intra-SR free Ca2+ is 1 mM.

Measurements suggest the local free Ca2+ level in the SR falls roughly 50% (to ~0.5 mM) during a spark [7,35,36]. Mathematical modeling, however, suggests it may fall even further (90%) depending on the speed of release termination and rate of Ca2+ transfer between regions inside the SR [8,9]. Our extensive single RyR2 permeation works [33,34,37-41] indicate that single RyR2 Ca2+ current amplitude (at 0 mV) will vary almost proportionally with local SR Ca2+ load. Thus, single RyR2 Ca2+ current (at 0 mV) may be 0.35 pA when a spark begins but would fall to 0.175 pA if local load decreased by 50% (or to 0.035 pA if it decreased by 90%) when the spark terminates.

The Local Cytosolic Ca2+ Signal Generated by a Single RyR2 Opening

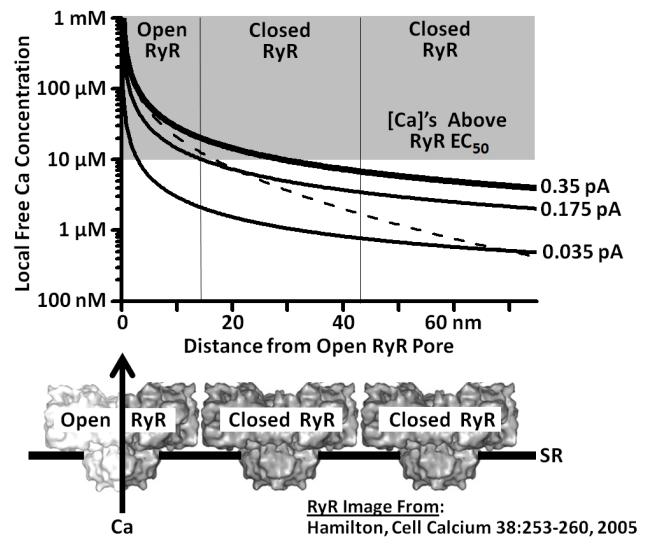

The local cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated around a Ca2+ point source, like an open RyR2 conducting a 0.35 pA Ca2+ current, can be calculated using standard diffusion theory [42-44]. Figure 1 plots the steady state local Ca2+ concentration around a 0.35 pA point source as a function of distance (thick solid curve). For the RyR, these steady state concentrations are likely established in <10 μs [45,46] and are sustained as long as the current is sustained. The elevation in local cytosolic Ca2+ generated by a 0.175 and 0.035 pA current are also shown (thin solid curve). The dashed curve is the elevation in local cytosolic Ca2+ level with the 0.35 pA current in the presence of 1 mM cytosolic BAPTA, a fast-binding Ca2+ buffer. To help interpret these curves, 3 adjacent RyR2s are depicted at the bottom of Figure 1. The adjacent RyR2s shown roughly reflect the known physical dimensions of the RyR2 [47,48] (central pore, cytosolic domain ~28 nm wide) as well as the known spacing between RyR2s at a release site [49] (center-to-center distance ~30 nm). The center of one RyR2 (Fig. 1, bottom left) is aligned with 0 nm on the plot and thus this RyR2 can be envisioned as the Ca2+ point source that is generating the various Ca2+ plots above.

FIGURE 1.

Local Ca2+ diffusion around one open RyR2 channel. Local free Ca2+ concentration is plotted as a function of distance from the center of a Ca2+ point source of 0.35, 0.175 or 0.035 pA. Local Ca2+ concentrations were calculated as specified elsewhere [44]. Three RyR channels (one open, two closed) are illustrated at bottom to provide interpretive context. The Ca2+ activation EC50 of single the cardiac RyR channel in cell-like salt solution is ~10 μM [30] and super-EC50 Ca2+ concentrations are indicated by the shaded area on the plot. The dashed line represents local Ca2+ levels when there is a 0.35 pA Ca2+ current with 1 mM cytosolic BAPTA present.

In cell-like salt solutions, the measured RyR2 cytosolic Ca2+ activation EC50 is ~10 μM [27,30]. Figure 1 shows that the physiological RyR2 Ca2+ current of 0.35 pA will elevate the local cytosolic Ca2+ to >20 μM around the open RyR2 and to >10 μM across half of the immediately adjacent RyR2. The super-EC50 Ca2+ levels over an adjacent closed RyR2 would intuitively trigger inter-RyR2 CICR and initiate a spark. When the single RyR2 Ca2+ current is 0.175 pA (not 0.35 pA), there is sub-EC50 Ca2+ levels over the adjacent RyR2 and thus inter-RyR2 CICR would be less likely to occur. Note that these predictions are based on well-established experimental measurements (RyR2 Ca2+ EC50, RyR2 current amplitude and RyR2 physical size/spacing in cells) as well as simple diffusion theory. How accurately this describes local RyR2 Ca2+ cross talk in living cells remains to be determined.

If single RyR2 Ca2+ current is large enough to act upon the Ca2+ regulatory sites of a neighboring RyR2, then should also have some action on the Ca2+ regulatory sites of RyR2 actually mediating the current. After all, the Ca2+ regulatory sites of the RyR2 mediating the current are much closer to the open pore. We will define this prospect as auto-RyR2 Ca2+ feed through. Auto-RyR2 Ca2+ feed through is when the Ca2+ flux through an open RyR2 feeds back and acts on the cytosolic regulatory sites of the same RyR2 conducting the flux. This is not inter-RyR2 CICR where the Ca2+ flux through an open RyR2 acts on the cytosolic regulatory sites of a nearby neighboring RyR2 channel. Several studies have reported auto-RyR2 Ca2+ feed through [43,44,50,51]. However, these studies usually done with super-physiological RyR2 Ca2+ fluxes (>2.5 pA) and/or enhanced RyR2 cytosolic Ca2+ sensitivity. The cytosolic Ca2+ sensitivity is typically enhanced using caffeine or ATP (without cytosolic Mg2+ present). In cell-like salt solutions, the physiological Ca2+ flux is considerably smaller and cytosolic Ca2+ sensitivity is normally not pharmacologically potentiated in cells. In cell-like salt solutions, experiments show that there is very little (if any) auto-RyR2 Ca2+ feed through activation in cells [44], despite popular belief.

While experiments show there is little (if any) auto-RyR2 feed through, the explanation is not totally clear. Figure 1 illustrates that the cytosolic local free Ca2+ around an open RyR2 mediating even a small Ca2+ current is above that RyR2’s cytosolic Ca2+ EC50 (~10 μM). Also, the cytosolic Ca2+ EC50 of Cs+ conducting (no Ca2+ flux) and Ca2+ conducting (>4 pA of Ca2+ flux) RyR2’s are the same (~2 μM) [44]. These observations imply that a RyR2’s cytosolic Ca2+ activation sites are somehow insensitive to the Ca2+ fluxing though that same channel’s open pore. In other words, single RyR2’s are immune to auto-RyR2 Ca2+ feed through activation [44]. We have speculated that this immunity may arise because Ca2+ is already occupying the cytosolic activation site(s) of the open RyR2 [44] and thus the fluxed Ca2+ has little effect. Note that cytosolic Ca2+ activation sites on neighboring RyR2s would not be occupied. Thus, the Ca2+ fluxing through an open RyR2 can act on the cytosolic sites of neighboring RyR2’s and drive inter-RyR2 CICR. The current control discussed in this review applies to inter-RyR2 CICR, not auto-RyR2 feed through activation.

Possible Role of Inter-RyR2 Current Control of Sparks

Logically, the likelihood of inter-RyR2 CICR occurring at a SR Ca2+ release site will critically depend on the magnitude of the local cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by the opening of an individual RyR2 channel [20-25,27]. The magnitude of this signal will depend on both the amplitude of the single RyR2 Ca2+ current and the duration of the opening event. It is clear that local SR Ca2+ load modulates single RyR2 open times (duration and frequency) by acting on intra-SR RyR2 Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms [11-14] perhaps in part by modulating the RyR2’s cytosolic Ca2+ and/or ATP sensitivity [11,13,52]. Local SR Ca2+ load also determines single RyR2 current amplitude because it sets the SR Ca2+ driving force. These two actions likely work in concert to govern the likelihood of inter-RyR2 CICR (sparks) and generate the load sensitivity of SR Ca2+ release.

During diastole in cardiac cells, there is always a low but finite probability that a RyR2 will open spontaneously. When one does, the likelihood that it triggers inter-RyR2 CICR (i.e. a spark) depends on the magnitude of the local cytosolic Ca2+ signal it generates. Since RyR2 open times are exponentially distributed, there are many more short than long spontaneous openings. We have reported that only the longest single RyR2 openings are likely to drive inter-RyR2 CICR and evoke sparks [30]. This suggests spark frequency is normally low during diastole primarily because spontaneous long duration RyR2 openings are relatively rare.

When local SR load rises above normal levels, each spontaneous single RyR2 opening will carry a larger than normal Ca2+ flux and thus generate a larger than normal local Ca2+ signal. Consequently, shorter openings (and there are exponentially more of them) will be sufficient to drive inter-RyR2 CICR (sparks). If so, then spark frequency will increase nearly exponentially as local load rises. Moreover, higher intra-SR Ca2+ also shifts (via intra-SR RyR2 regulatory mechanisms) the distribution of RyR2 open times to longer values [11,13,53], so spark frequency will sky rocket (super-exponentially increase) as local SR Ca2+ load increases. The sparks generated will be bigger because the larger local Ca2+ signals (generate by each individual opening) will recruit more RyR2s per spark. The resulting frequent large sparks are more likely to trigger arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves. On the other hand, lower SR Ca2+ load simultaneously decreases single RyR2 current amplitude (due to smaller Ca2+ driving force) and shortens single RyR2 open time (via intra-SR Ca2+ regulator mechanisms). The possible ramifications of the latter warrants further consideration.

As local load falls during a spark, the cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by the open RyR2’s will intuitively become at some point too small to drive (or sustain) inter-RyR2 CICR. At this point, RyR2’s that spontaneously close will no longer be re-activated by inter-RyR2 CICR. Eventually, all RyR2’s will close and local release will terminate. In this scheme, sparks terminate because RyR2’s inherently/spontaneously close and fail to re-open. They fail to re-open because the cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by individual RyR2 openings is no longer sufficient to drive inter-RyR2 CICR. We call this current-dependent termination mechanism pernicious attrition. Pernicious attrition is not stochastic attrition. Stochastic attrition specifically refers to the probability that all open RyR2 will spontaneously close at the same moment. During pernicious attrition, RyR2 closing is asynchronous. We call it pernicious because the smaller RyR2 Ca2+ current devastates inter-RyR2 CICR in a way that is not easily seen or noticed. This is an interesting possibility because termination is commonly attributed solely to processes that directly turn-off RyR2’s. Pernicious attrition contributes to termination by limiting a signal that turns-on RyR2s (i.e. the local Ca2+ trigger signal that drives inter-RyR2 CICR). We have presented a preliminary report describing this mechanism [26]. Subsequently Laver et al [25] described similar process that they refer to as “induction decay”. Much more work is clearly required to fully understand the potential contribution of these mechanisms to spark local control.

Single RyR2 Current and Spark/Wave Control

Single inter-RyR2 current control likely contributes to the local control of sparks and waves in cardiac muscle cells. The key word here is contributes. For example, the presence of current control does not mean that calsequestrin (CASQ) dependent RyR2 luminal Ca2+ regulation is not important. Current control very likely works in synergy with CASQ-dependent RyR2 regulation during overall spark local control. Also, the existence of pernicious attrition does not mean that other potential CICR termination mechanisms are not significant. Current control likely operates in concert with these other local control phenomena to terminate sparks.

Some possible contributions of current control during various spark/wave phenomena are outlined in Table 1. Current control likely contributes to the luminal Ca2+ sensitivity of sparks. It may help explain why sparks terminate when SR Ca2+ falls to a set termination threshold and why that threshold changes when caffeine is present. Current control also explains the existence of non-spark SR Ca2+ leak as recently described by Williams et al. [23] and Sato & Bers [24]. It also may help explain how drugs that shorten RyR2 open time end up limiting SR Ca2+ waves. Indeed, few proposed local control process in our experience integrate this smoothly and broadly with our present understanding of CICR local control.

Table 1.

| Finding | Current Control Contribution |

|---|---|

|

Intra-SR RyR2 Ca2+ Regulatory Sites

Gyorke et al. (2004) Jiang et al. (2004) |

These sites modulate single RyR2 open time (OT). Higher load increases OT while lower loads decrease it. Both single RyR2 current amplitude (defined by trans-SR Ca driving force) and RyR2 OT (in part defined by intra-SR Ca sites) determine the size* of local cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by a single RyR2 opening. This in turn determines the likelihood of inter-RyR2 CICR. |

|

SR Load Controls Spark Frequency

Lukyanenko et al. (2001) Zima et al. (2010) |

Load influences both single RyR2 current amplitude (via Ca driving force) and RyR2 OT (via intra-SR Ca sites). This duel action renders inter-RyR2 CICR exquisitely sensitive to even small changes in local SR Ca load. |

|

Sparks terminate when SR Ca2+

falls to a termination threshold Rice et al (1999), Hinch (2004), Zima et al (2008), Ramay et al (2011) & Sato and Bers (2011) |

As local SR load falls, single RyR2 current amplitude gets smaller and RyR2 OTs shorter. At some point (threshold), RyR2’s spontaneously that close will no longer be re-activated by local CICR and will remain closed. Soon all RyR2’s will be closed and local spark terminated. We call this process pernicious attrition. |

|

Sparks Peak Before Underlying

Local SR Ca2+ Release Ends Zima et al (2008) |

This implies RyR2s close asynchronously during spark termination and is consistent with current control and pernicious attrition (see above). |

|

Calsequestrin KO Causes CPVT but

SR Release Still Load Dependent Knollmann etal. (2006) |

Calsequestrin is participates in intra-SR RyR2 Ca2+ regulation and its absence alters this regulation leading to larger more frequent sparks. Load still defines single RyR2 current amplitude so release/sparks are still load dependent. |

|

RyR2, CASQ or TD Mutations Can

Promote Ca2+ Waves Causing CPVT Priori et al. (2002) & Roux-Buisson (2012) Terentyev et al. (2008) |

The RyR2-TD-CASQ complex participates in intra-SR RyR2 Ca2+ regulation and alterations in this complex result in larger more frequent waves. They likely lengthen RyR2 OT, increasing likelihood of inter-RyR2 CICR at any set load. |

|

Caffeine Promotes Sparks/Waves

Trafford et al. (1995) Porta et al. (2011) |

Caffeine makes single RyR2 more Ca2+ sensitive. Consequently, smaller single RyR2 Ca2+ currents can drive inter-RyR2 CICR, increasing spark/wave frequency. |

|

Caffeine Reduces SR Ca2+ Spark

Termination Threshold Domeier et al. (2010) |

Since caffeine heightens RyR2 Ca2+ sensitivity, local load must fall further before the cytosolic signal driving inter-RyR2 CICR fails (i.e. pernicious attrition starts). |

|

Non-spark SR Ca2+ Leak Exists

Zima et al. (2010) Santiago et al. (2010) |

During diastole, single RyR2 spontaneously open at a very low frequency. If the cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by an opening fails to trigger inter-RyR2 CICR, then Ca2+ released during that opening represents non-spark SR Ca2+ leak. |

|

Ryanodol & Imperatoxin Evoke

Trains of Sparks at SR Release Sites Terentyev et al. (2002) Ramos-Franco et al. (2010) |

These drugs likely evoke sustained sub-conductance openings of 1 or 2 RyR2’s at a release site, generating a prolonged elevation in the local cytosolic Ca2+ level. This makes RyR2 more likely to open and/or respond to smaller than normal local Ca2+ trigger stimuli (generated by local single RyR2 openings). |

|

Carvedilol & Flecainide Reduce

RyR2 Open Time, Stopping CPVT Watanabe et al. (2009) Zhou et al. (2011) |

The drug-evoked reduction in RyR2 OT decreases the size* of the cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by an individual RyR2 opening. This reduces the likelihood of inter-RyR2 CICR and limiting the initiation of sparks/waves that trigger CPVT. |

size refers to the combination amplitude, duration and spatial width of the local Ca2+ trigger signal.

What is the experimental evidence supporting the existence of inter-RyR2 CICR current control? In cells, single RyR2 Ca2+ current and SR load inherently vary in parallel. This makes it very difficult to distinguish their individual regulatory contributions. We recently devised a way to differentially manipulate single RyR2 Ca2+ current and SR Ca2+ load in permeabilized cardiomyocytes [27]. This method involves replacing cytosolic K with large RyR2-permeable organic cations that enter the RyR2 pore and consequently limits Ca2+ flux through the pore. Single channel studies confirmed that this experimental manipulation does not alter other aspects of RyR2 function (i.e. its gating). Spark frequency followed the change in single RyR2 Ca2+ current (frequency decreased), not the change in load. Sparks terminated earlier even though SR Ca2+ load was higher, suggesting local CICR termination is tightly linked to decreasing single RyR2 current. We also reported that high SR Ca2+ loads did not evoke Ca2+ waves when the large RyR2-permeable organic cation was present (i.e. when the single RyR2 Ca2+ current was limited). At the high SR loads, subsequent removal of the large organic cation immediately resulted in waves [27]. This suggests waves (like sparks) are not solely governed by intra-SR Ca2+ acting at intra-SR RyR2 Ca2+ regulatory sites. Another process, one linked to single RyR2 current amplitude also plays a substantial role in local spark/wave control [27]. That other process is likely current control.

There is also evidence supporting current control that does not involve the use of non-physiological large organic cations. In SR-load controlled permeabilized cardiomycytes, Bovo et al. [54] recently reported that spark frequency decreases when a small amount of cytosolic BAPTA, instead of EGTA, is present. Since load was controlled, the change in spark frequency was not due to a change in SR Ca2+ load. They reasoned that BAPTA, a fast Ca2+ buffer, had likely limited cytosolic Ca2+ diffusion around the open RyR2 pore, in effect reducing the local cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by each open RyR2. The reduced signal would be less likely to activate neighboring RyR2’s (i.e. driving inter-RyR2 CICR). This does not prove current control but it is consistent with it. Also, flecainide [55] and carvedilol [56] both reduce single RyR2 mean open time, which will reduce the size the cytosolic Ca2+ signal generated by an individual RyR2 channel opening. Current control would explain why these drugs ultimately reduce SR Ca2+ wave frequency. Thus, it seems clear that inter-RyR2 CICR current control plays at least some role in regulating SR Ca2+ sparks.

One caveat, when considering the possibility of inter-RyR2 CICR current control, is the existence of RyR2 coupled gating. In our hands [27], individual RyR2s incorporated into planar bilayers have a mean open time of 8.5 ms when activated by 10 μM cytosolic Ca2+ (1 mM Ca2+ luminal). Since the average spark time-to-peak (TTP) in analogous solutions is ~20 ms, we suggest that than 96% of measured single RyR2 openings are shorter than spark TTP [27]. This implies individual RyR2s may open and close many times during a spark. However, there is evidence that gating of neighboring RyR2s may be allosterically coupled by the FK-506 binding protein (FKBP) [57]. This allosteric coupling is proposed to functionally couple channels so that neighboring RyR2s open and close together (i.e. in a lock-step fashion). Lock-step closing of multiple channels would represent a robust means to terminate local CICR. Consequently, allosteric coupled gating has been included in various theoretical models that describe CICR local control [21,58,59]. Does such allosteric coupling exist in cells? This is a difficult question to answer. Allosterically coupled RyR2 gating has been observed in vitro in a few single channel studies [57,60]. However, functional coordination of neighboring RyR2 channels by inter-RyR2 CICR has also been reported in some in vitro studies [27,44,61]. In our view, the almost incomprehensible free energy that would be required to allosterically couple the gating of huge macromolecules like RyR2 channels strongly suggests that it is unlikely to occur in cells. Further, simultaneous sparks and blink measurements indicate that sparks peak (i.e. release termination begins) before the underlying SR Ca2+ release ends [7]. This implies RyR2 closing during spark termination is not synchronous. This is consistent with the relatively rounded peaks of cardiac sparks (i.e. synchronous lock-step closing of all active RyR2s would intuitively generate sharp spark peaks). Of course, these observations might be explained if small subgroups of allosterically coupled RyR2s were closing asynchronously [62]. The more prudent explanation, however, is that individual RyR2s are simply closing asynchronously during spark termination. If so, then RyR2 function during a spark is interdependent because neighboring channels interact through inter-RyR2 CICR but each active channel gates individually (i.e. not in an allosterically coupled fashion).

In summary, experiment and modeling both indicate that the single RyR2 Ca2+ current amplitude plays a substantial regulatory role in the local control of inter-RyR CICR at SR Ca2+ release sites in cardiac muscle. Local inter-RyR2 CICR current control is load dependent because the trans-SR Ca2+ driving force is determined by the local SR Ca2+ load. We suggest that inter-RyR2 CICR current control works in synergy with other well-established RyR luminal Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms to generate the load sensitivity of cardiac SR Ca2+ release. We have also discussed a process we call pernicious attrition that describes the point where the single RyR2 Ca2+ current (load) becomes insufficient to support the continuation of local inter-RyR2 CICR.

Highlights.

Single RyR2 current is a key determinant of local inter-RyR2 CICR control.

This local current control of CICR works in synergy with other RyR2 regulatory mechanisms.

Pernicious attrition may contribute to the termination of local CICR events.

Acknowledgements

This effort was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-HL057832 and R01-AR054098 (M.F.). We would like to thank Dr. Demetrio J. Santiago for help preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None Declared

References

- [1].Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zima AV, Bovo E, Bers DM, Blatter LA. Ca2+ spark-dependent and -independent sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in normal and failing rabbit ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 2010;588:4743–4757. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.197913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Santiago DJ, Curran JW, Bers DM, Lederer WJ, Stern MD, Ríos E, et al. Ca sparks do not explain all ryanodine receptor-mediated SR Ca leak in mouse ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2111–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wier WG, ter Keurs HEDJ, Marban E, Gao WD, Balke CW. Ca2+ ‘Sparks’ and Waves in Intact Ventricular Muscle Resolved by Confocal Imaging. Circulation Research. 1997;81:462–469. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Díaz ME, O’Neill SC, Eisner DA. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content fluctuation is the key to cardiac alternans. Circ. Res. 2004;94:650–656. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000119923.64774.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lukyanenko V, Gyorke S. Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves in saponin-permeabilized rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1999;521(Pt 3):575–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zima AV, Picht E, Bers DM, Blatter LA. Termination of cardiac Ca2+ sparks: role of intra-SR [Ca2+], release flux, and intra-SR Ca2+ diffusion. Circ. Res. 2008;103:e105–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.183236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sobie EA, Lederer WJ. Dynamic local changes in sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium: physiological and pathophysiological roles. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012;52:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hake J, Edwards AG, Yu Z, Kekenes-Huskey PM, Michailova AP, McCammon JA, et al. Modelling cardiac calcium sparks in a three-dimensional reconstruction of a calcium release unit. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2012;590:4403–4422. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.227926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fill M, Copello JA. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gyorke I, Hester N, Jones LR, Gyorke S. The role of calsequestrin, triadin, and junctin in conferring cardiac ryanodine receptor responsiveness to luminal calcium. Biophys J. 2004;86:2121–8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74271-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Beard NA, Laver DR, Dulhunty AF. Calsequestrin and the calcium release channel of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;85:33–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Qin J, Valle G, Nani A, Nori A, Rizzi N, Priori SG, et al. Luminal Ca2+ regulation of single cardiac ryanodine receptors: insights provided by calsequestrin and its mutants. J. Gen. Physiol. 2008;131:325–334. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].di Barletta MR, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Nori A, Memmi M, Terentyev D, Turcato F, et al. Clinical phenotype and functional characterization of CASQ2 mutations associated with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2006;114:1012–1019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.623793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liu N, Colombi B, Memmi M, Zissimopoulos S, Rizzi N, Negri S, et al. Arrhythmogenesis in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: insights from a RyR2 R4496C knock-in mouse model. Circ. Res. 2006;99:292–298. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000235869.50747.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kannankeril PJ, Mitchell BM, Goonasekera SA, Chelu MG, Zhang W, Sood S, et al. Mice with the R176Q cardiac ryanodine receptor mutation exhibit catecholamine-induced ventricular tachycardia and cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:12179–12184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600268103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kalyanasundaram A, Bal NC, Franzini-Armstrong C, Knollmann BC, Periasamy M. The calsequestrin mutation CASQ2D307H does not affect protein stability and targeting to the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum but compromises its dynamic regulation of calcium buffering. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:3076–3083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gyorke S, Volpe P, Priori SG, di Barletta MR, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Nori A, et al. Clinical phenotype and functional characterization of CASQ2 mutations associated with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2006;114:1012–1019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.623793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Roux-Buisson N, Cacheux M, Fourest-Lieuvin A, Fauconnier J, Brocard J, Denjoy I, et al. Absence of triadin, a protein of the calcium release complex, is responsible for cardiac arrhythmia with sudden death in human. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:2759–2767. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rice JJ, Jafri MS, Winslow RL. Modeling gain and gradedness of Ca2+ release in the functional unit of the cardiac diadic space. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1871–1884. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77030-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hinch R. A mathematical analysis of the generation and termination of calcium sparks. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1293–1307. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74203-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ramay HR, Liu OZ, Sobie EA. Recovery of cardiac calcium release is controlled by sarcoplasmic reticulum refilling and ryanodine receptor sensitivity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;91:598–605. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Williams GSB, Chikando AC, Tuan H-TM, Sobie EA, Lederer WJ, Jafri MS. Dynamics of calcium sparks and calcium leak in the heart. Biophys. J. 2011;101:1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sato D, Bers DM. How does stochastic ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca leak fail to initiate a Ca spark? Biophys. J. 2011;101:2370–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Laver DR, Kong CHT, Imtiaz MS, Cannell MB. Termination of calcium-induced calcium release by induction decay: An emergent property of stochastic channel gating and molecular scale architecture. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yonkunas MJ, Fill M, Gillespie D. Modeling Ca Induced Ca Release Between Neighboring Ryanodine Receptors. Biophysical Journal. 2012;102:138a. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Guo T, Gillespie D, Fill M. Ryanodine Receptor Current Amplitude Controls Ca2+ Sparks in Cardiac Muscle. Circulation Research. 2012 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tinker A, Williams AJ. Divalent cation conduction in the ryanodine receptor channel of sheep cardiac muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Gen. Physiol. 1992;100:479–493. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Somlyo AV, McClellan G, Gonzalez-Serratos H, Somlyo AP. Electron probe X-ray microanalysis of post-tetanic Ca2+ and Mg2+ movements across the sarcoplasmic reticulum in situ. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:6801–6807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Porta M, Zima AV, Nani A, Diaz-Sylvester PL, Copello JA, Ramos-Franco J, et al. Single ryanodine receptor channel basis of caffeine’s action on Ca2+ sparks. Biophys. J. 2011;100:931–938. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mejia-Alvarez R, Kettlun C, Rios E, Stern M, Fill M. Unitary Ca2+ current through cardiac ryanodine receptor channels under quasi-physiological ionic conditions. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:177–86. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kettlun C, Gonzalez A, Rios E, Fill M. Unitary Ca2+ current through mammalian cardiac and amphibian skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor Channels under near-physiological ionic conditions. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:407–17. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gillespie D, Fill M. Intracellular calcium release channels mediate their own countercurrent: the ryanodine receptor case study. Biophys. J. 2008;95:3706–3714. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gillespie D, Chen H, Fill M. Is ryanodine receptor a calcium or magnesium channel? Roles of K(+) and Mg(2+) during Ca(2+) release. Cell Calcium. 2012;51:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shannon TR, Guo T, Bers DM. Ca2+ scraps: local depletions of free [Ca2+] in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum during contractions leave substantial Ca2+ reserve. Circ Res. 2003;93:40–5. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000079967.11815.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Brochet DXP, Yang D, Di Maio A, Lederer WJ, Franzini-Armstrong C, Cheng H. Ca2+ blinks: rapid nanoscopic store calcium signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500059102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gillespie D, Xu L, Wang Y, Meissner G. (De)constructing the ryanodine receptor: modeling ion permeation and selectivity of the calcium release channel. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:15598–15610. doi: 10.1021/jp052471j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gillespie D, Giri J, Fill M. Reinterpreting the anomalous mole fraction effect: the ryanodine receptor case study. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2212–2221. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gillespie D. Energetics of divalent selectivity in a calcium channel: the ryanodine receptor case study. Biophys. J. 2008;94:1169–1184. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.116798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wang Y, Xu L, Pasek DA, Gillespie D, Meissner G. Probing the role of negatively charged amino acid residues in ion permeation of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Biophys. J. 2005;89:256–265. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.056002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Xu L, Wang Y, Gillespie D, Meissner G. Two Rings of Negative Charges in the Cytosolic Vestibule of Type-1 Ryanodine Receptor Modulate Ion Fluxes. Biophysical Journal. 2006;90:443–453. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stern MD. Theory of excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Biophys J. 1992;63:497–517. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81615-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Xu L, Meissner G. Regulation of cardiac muscle Ca2+ release channel by sarcoplasmic reticulum lumenal Ca2+ Biophys. J. 1998;75:2302–2312. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77674-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Liu Y, Porta M, Qin J, Ramos J, Nani A, Shannon TR, et al. Flux regulation of cardiac ryanodine receptor channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010;135:15–27. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Soeller C, Cannell MB. Numerical simulation of local calcium movements during L-type calcium channel gating in the cardiac diad. Biophys. J. 1997;73:97–111. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Langer GA, Peskoff A. Role of the diadic cleft in myocardial contractile control. Circulation. 1997;96:3761–3765. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Samsó M, Wagenknecht T, Allen PD. Internal structure and visualization of transmembrane domains of the RyR1 calcium release channel by cryo-EM. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:539–544. doi: 10.1038/nsmb938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Serysheva II, Hamilton SL, Chiu W, Ludtke SJ. Structure of Ca2+ release channel at 14 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca(2+) release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1528–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sitsapesan R, Williams AJ. Regulation of the gating of the sheep cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-release channel by luminal Ca2+ J. Membr. Biol. 1994;137:215–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00232590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Laver DR. Ca2+ stores regulate ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels via luminal and cytosolic Ca2+ sites. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2007;34:889–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tencerová B, Zahradníková A, Gaburjáková J, Gaburjáková M. Luminal Ca2+ controls activation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor by ATP. J. Gen. Physiol. 2012;140:93–108. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kong H, Wang R, Chen W, Zhang L, Chen K, Shimoni Y, et al. Skeletal and cardiac ryanodine receptors exhibit different responses to Ca2+ overload and luminal ca2+ Biophys. J. 2007;92:2757–2770. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.100545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bovo E, Mazurek SR, Fill M, Zima AV. Effects of Cytosolic Ca Buffering on Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca Leak in Permeabilized Rabbit Ventricular Myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 2012;102:103a. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Watanabe H, Chopra N, Laver D, Hwang HS, Davies SS, Roach DE, et al. Flecainide prevents catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice and humans. Nat. Med. 2009;15:380–383. doi: 10.1038/nm.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Zhou Q, Xiao J, Jiang D, Wang R, Vembaiyan K, Wang A, et al. Carvedilol and its new analogs suppress arrhythmogenic store overload-induced Ca2+ release. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1003–1009. doi: 10.1038/nm.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Marx SO, Gaburjakova J, Gaburjakova M, Henrikson C, Ondrias K, Marks AR. Coupled gating between cardiac calcium release channels (ryanodine receptors) Circ Res. 2001;88:1151–8. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Stern MD, Song LS, Cheng H, Sham JS, Yang HT, Boheler KR, et al. Local control models of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. A possible role for allosteric interactions between ryanodine receptors. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:469–89. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.3.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sobie EA, Dilly KW, Santos Cruz J, Lederer WJ, Jafri MS. Termination of cardiac Ca(2+) sparks: an investigative mathematical model of calcium-induced calcium release. Biophys. J. 2002;83:59–78. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gaburjakova J, Gaburjakova M. Identification of changes in the functional profile of the cardiac ryanodine receptor caused by the coupled gating phenomenon. J. Membr. Biol. 2010;234:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Laver DR. Coupled calcium release channels and their regulation by luminal and cytosolic ions. Eur. Biophys. J. 2005;34:359–368. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0483-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Calcium sparks. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:1491–1545. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]