Abstract

L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs) are essential for generation of the electrical and mechanical properties of cardiac muscle. Furthermore, regulation of LTCC activity plays a central role in mediating the effects of sympathetic stimulation on the heart. The primary mechanism responsible for this regulation involves β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) stimulation of cAMP production and subsequent activation of protein kinase A (PKA). Although it is well established that PKA-dependent phosphorylation regulates LTCC function, there is still much we do not understand. However, it has recently become clear that the interaction of the various signaling proteins involved is not left to completely stochastic events due to random diffusion. The primary LTCC expressed in cardiac muscle, CaV1.2, forms a supramolecular signaling complex that includes the β2AR, G proteins, adenylyl cyclases, phosphodiesterases, PKA, and protein phosphatases. In some cases, the protein interactions with CaV1.2 appear to be direct, in other cases they involve scaffolding proteins such as A kinase anchoring proteins and caveolin-3. Functional evidence also suggests that the targeting of these signaling proteins to specific membrane domains plays a critical role in maintaining the fidelity of receptor mediated LTCC regulation. This information helps explain the phenomenon of compartmentation, whereby different receptors, all linked to the production of a common diffusible second messenger, can vary in their ability to regulate LTCC activity. The purpose of this review is to examine our current understanding of the signaling complexes involved in cardiac LTCC regulation.

Keywords: Calcium channel, β-adrenergic receptor, A kinase anchoring protein, E type prostaglandin receptor, cardiac myocyte, protein kinase A

1. Introduction

The proximity of the constituent components of a signaling pathway often plays a critical role in ensuring the speed, efficiency, and specificity of the functional responses they produce. This is especially true for the signaling mechanisms involved in regulating many different ion channels. Ion channels forming signaling complexes with kinase(s) and phosphatase(s) is a common theme [1]. While the localization of such signaling molecules is often achieved through direct protein-protein interactions, spatial organization can also be achieved indirectly via scaffolding proteins as well as the targeting of the relevant control elements to specific subcellular locations or lipid domains in the plasma membrane [1–3]. The spatial restriction of signaling also extends to aspects of those pathways that involve diffusible second messengers, such as cAMP. Accordingly, signaling complexes often include receptors and enzymes such as adenylyl cyclase that are responsible for second messenger production, as well as proteins such as phosphodiesterases (PDEs), which are involved in second messenger catabolism. The primary focus of this review will be on the signaling complexes important in maintaining the fidelity of L-type Ca2+ channel responses involving protein kinase A (PKA) in the heart.

2. Ca2+ Channels in the Heart

Ca2+ is a potent second messenger that controls a variety of cellular functions [4, 5]. This is particularly true in the heart, where the influx of Ca2+ through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels plays an essential role in regulating action potential duration, triggering myocyte contraction, and controlling gene transcription [6]. Thus, they are an important target for regulating cellular function by a number of different signal transduction pathways, including those involving PKA.

3. Molecular Structure of L-Type Ca2+ Channels

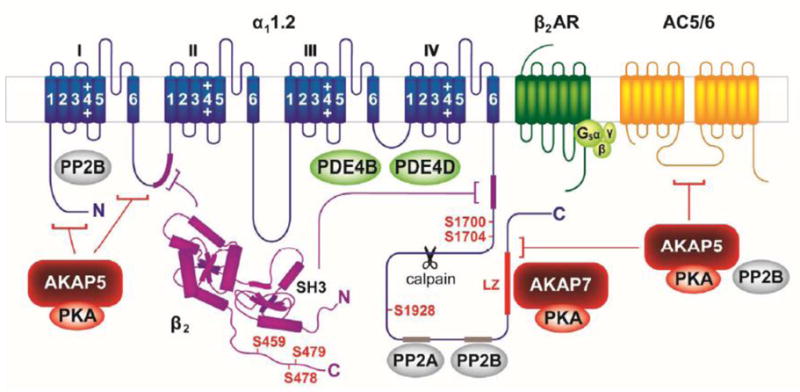

There are four types of LTCC, CaV1.1–1.4, each of which exists as a multimeric protein complex consisting of one of four different corresponding α1 subunits (α11.1–1.4) together with auxiliary β, α2δ, and γ subunits [7] (Fig. 1). The α1 subunit forms the ion-conducting pore and defines the specific type of Ca2+ channel. It consists of four homologous domains (I-IV) each containing six transmembrane segments (S1–S6) and a pore forming P-loop between segments 5 and 6. CaV1.2 is the predominant LTCC expressed in ventricular myocytes, while both CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 are expressed in atrial cells as well sinoatrial and atrioventricular node cells [8].

Figure 1.

The CaV1.2 signaling complex includes the α11.2 subunit, β2 subunit, A kinase anchoring proteins 5 and 7 (AKAP5 and AKAP7), protein kinase A (PKA), protein phosphatases 2A and 2B (PP2A and PP2B), the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), adenylyl cyclase 5/6 (AC5/6), stimulatory G protein (Gs), and phosphodiesterases 4B and 4D (PDE4B and PDE4D). PKA phosphorylation sites are indicated in red; sites of interaction with binding partners are indicated by corresponding color-coded segments or brackets. Site cleaved by calpain indicated by scissors. See text for details.

The distal C terminus (DCT) of the α11.2 subunit can undergo proteolytic cleavage by the Ca2+-activated protease calpain resulting in a long and a short form [9, 10]. The DCT can remain associated with the truncated α11.2 subunit after cleavage via a non-covalent interaction [9, 11, 12]. Expression of truncated α11.2 alone produces currents that are significantly greater than those produced by the full length subunit [9, 11–14], suggesting that the DCT has an autoinhibitory effect. Consistent with this idea, coexpression of the DCT as an independent polypeptide together with the α11.2 short form results in a decrease in the current produced by the truncated subunit alone [12]. It has been reported that the majority of α11.2 in heart may exist in the cleaved state [10, 15], however, see Dai et al. 2009 for evidence that 50% or more may exist in its uncleaved, full length form [1]. The C terminal fragment of α11.2 has also been reported to act as a Ca2+ channel associated transcription factor (CCAT) regulating a wide range of genes affecting neuronal signaling and excitability [16]. Whether or not it serves such a function in the heart has yet to be determined.

There are four different β subunit genes (β1–β4). These can undergo alternative splicing, resulting in numerous isoforms [17]. In the cytosol, the β subunit promotes surface expression of the channel complex. Once at the membrane, the β subunit is found at the cytosolic face of the channel, where it affects voltage-dependent activation and inactivation [18–20]. The α2δ subunits are generated from a single gene product, which is proteolytically cleaved but rejoined by disulfide linkage. The α2 subunit is extracellular, while the δ subunit consists of a single transmembrane segment with short intracellular and extracellular segments [21]. Like the β subunit, the α2δ subunits promote surface expression of the channel complex in addition to affecting channel gating [18, 22, 23]. In cardiac muscle, the CaV1.2 complex also includes a γ subunit, which can affect both activation and inactivation [24].

4. Regulation of CaV1.2

The regulation of CaV1.2 has been extensively studied because of its central role in contributing to the electrical and mechanical properties of the heart. Influx of Ca2+ through LTCCs is responsible for maintaining membrane depolarization during the plateau of the cardiac action potential. Subsequent inactivation then allows repolarization thus affecting action potential duration. In this way LTCCs play a critical role in determining refractory period duration, thereby ensuring that electrical activation of the myocardium occurs in the appropriate sequence [25]. Both gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations have been associated with cardiac arrhythmias [26, 27]. Influx of Ca2+ through CaV1.2 channels also has an essential function in excitation-contraction coupling by triggering the release of Ca2+ from type 2 ryanodine receptors (RyR2) found in the SR, which leads to subsequent contraction [6]. Consequently, β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) stimulation of LTCC activity plays a major role in the changes in both electrical and mechanical properties of the heart that occur during the fight-or-flight response [28]. Upon sympathetic stimulation, catecholamines bind to βARs, activating the stimulatory heterotrimeric G protein Gs by inducing the exchange of GDP for GTP on Gαs. Gαs dissociates from its Gβγ partners to stimulate AC production of cAMP, which in turn activates PKA [29].

4.1 G Protein Coupled Receptors

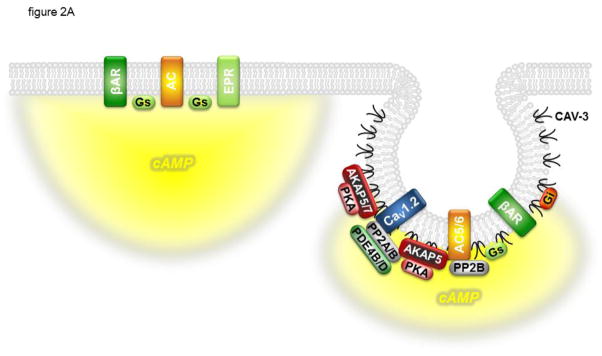

Many G Protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) stimulate cAMP production in the heart, but not all produce equivalent functional responses. This disparity includes differences in the ability of these receptors to regulate LTCC activity [30–33]. Such observations are a clear demonstration that cAMP signaling is spatially restricted or compartmentalized (Fig. 2). This situation reflects the fact that cAMP and PKA are not able to diffuse freely and that GPCRs, together with other components of the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway, are not uniformly distributed throughout the cell. Moreover, it suggests that CaV1.2 channels are in closer proximity to some receptors than others. Consistent with this idea, there is evidence that CaV1.2 interacts not only with PKA, but also many other components of the cAMP signaling pathway, including certain GPCRs.

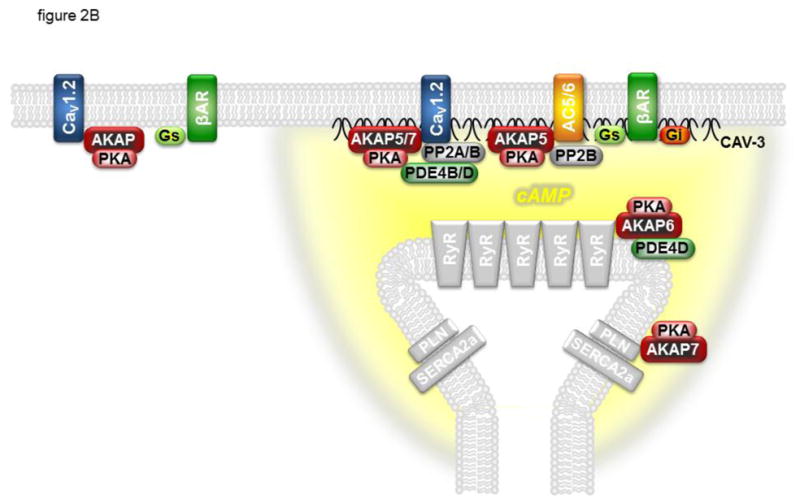

Figure 2.

CaV1.2 is regulated by cAMP confined to specific signaling domains. Panel A: β 1- and β2-adrenergic receptors (βARs) associated with CaV1.2 and caveolin-3 (CAV-3) signaling complexes in caveolae can stimulate cAMP production that regulates channel activity. E type prostaglandin receptors (EPRs) and βARs found outside of these signaling complexes can stimulate global changes in cAMP concentration that are not accessible to CaV1.2. Panel B: βARs associated with CaV1.2 and caveolin-3 at dyadic junctions, where caveolae are not present, can stimulate cAMP production that regulates channel activity as well as the activity of the type 2 ryanodine receptor (RyR2) and phospholamban (PLN). βARs not associated with CAV-3 and adenylyl cyclase (AC) are not able to stimulate cAMP production and regulates channel activity. In addition to the CaV1.2 signaling complex described in figure 1, CAV-3 associates with the inhibitory G protein (Gi), and AC5/6 associates with AKAP5 and PP2B. AKAPs also form signaling complexes with PLN and the type 2a sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA2a) as well as RyR2. See text for details.

4.1.1 β-Adrenergic Receptors

Both β1 and β2ARs are capable of stimulating cAMP production and enhancing sarcolemmal LTCC activity in cardiac ventricular myocytes. However, many studies suggest that only β1AR activation results in PKA dependent phosphorylation of non-sarcolemmal proteins, such as phospholamban and troponin I, which contribute to the increase in rate of myocyte contraction and relaxation characteristic of sympathetic stimulation [33–39]. These observations suggest that cAMP produced upon β1AR stimulation activates PKA more globally, whereas cAMP produced by β2AR stimulation is limited to activation of PKA specifically near LTCCs.

Demonstration of the locally restricted effect of β2AR stimulation in the heart was illustrated by the work of Chen-Izu et al. [40] using the cell attached configuration of the patch clamp technique to study regulation of LTCC activity in a patch of membrane where access to the extracellular surface was isolated from the rest of the intact cell by the recording electrode. Single LTCC activity was enhanced by activation of local β1 or β2ARs within the same patch of membrane from which channel activity was being recorded. However, while activation of distal β1ARs outside the isolated patch of membrane was still able to enhance channel activity, activation of distal β2ARs was not. Analogous results have been obtained in hippocampal neurons [41]. Such observations suggest that cAMP produced by β1AR stimulation is able to diffuse greater distances, while cAMP produced by β2AR stimulation is limited primarily to local PKA signaling domains. Contrary to this notion, MacDougal et al. [42], using FRET-based biosensors to measure responses in different subcellular compartments of intact myocytes, reported that β2AR production of cAMP may not be limited exclusively to PKA signaling domains. They also found evidence that localized PKA-dependent responses depends on phosphatase activity. On the other hand, Nikolaev et al. [43], using FRET-based biosensors together with scanning ion conductance microscopy, found that β2AR production of cAMP is specifically associated with the T-tubule network of normal adult cardiac myocytes, whereas β1ARs stimulating cAMP production appear to be distributed across the entire cell surface [43].

The observation that β2AR stimulation produces an effect limited to regulation of local LTCC function raises the possibility that the receptor might actually be part of a signaling complex that includes CaV1.2 as well as PKA. Consistent with this idea, coimmunoprecipitation studies revealed that the β2AR is constitutively associated with CaV1.2 along with Gs and AC [41, 44]. In vitro pull-down experiments with bacterially expressed fusion proteins indicate that the C terminus of the β2AR can directly bind to α 11.2 [41]. How Gs and AC are linked to CaV1.2 is unclear. However, A kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) associate with various AC isoforms including AC5 and AC6 (see section 4.3). Such interactions could recruit one or both AC isoforms to Cav1.2. In immunoprecipitation experiments, Balijepalli et al. [44] reported that CaV1.2 preferentially associates with β2ARs with little or no interaction with the β1ARs. The lack of CaV1.2 association with β1ARs has also been demonstrated in neuronal tissue [45]. Nichols et al. [46], on the other hand, found that both β1 and β2ARs co-immunoprecipiated with CaV1.2 from cardiac myocytes. However, the authors did not show control IgG precipitations leaving open the possibility that the β1 AR co-immunoprecipitation with CaV1.2 was not completely specific.

4.1.2 Prostaglandin Receptors

In the adult heart of various species, stimulation of EP2 or EP4 prostaglandin receptors (EPRs) increases cAMP and PKA activity in the cytosol, contrasting the ability of β1AR stimulation to activate both cytosolic and particulate PKA [31, 32, 47–50]. Despite the fact that EPR activation stimulates cAMP production, it has been reported to have no effect on Ca2+ transients, myocyte contraction, or LTCC activity in guinea-pig or rat ventricular myocytes [30–32] despite the fact that both β1AR and EPR activation produced a more global cAMP response that could be detected by a biosensor expressed throughout the cell [31, 51]. However, only β1AR stimulation produced a local cAMP response that could be detected by a biosensor targeted specifically to type II PKA signaling domains. This local cAMP response correlated with the ability of β1AR, but not EPR, stimulation to regulate LTCC function. This suggests that LTCCs are regulated by cAMP produced specifically in type II PKA signaling domains (Fig. 2A).

The reason cAMP produced by prostaglandins is unable to reach the PKA signaling domains and regulate LTCC activity is not known. One possibility is that phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity limits the diffusion of cAMP produced by EPRs from reaching CaV1.2 signaling complexes. Despite evidence that EPR stimulation can stimulate PDE activity [52], inhibiting PDE activity does not enable these receptors to regulate LTCC function [30, 31]. It has also been hypothesized that activation of Gi by EP3Rs might limit the reach of the cAMP response, similar to the way that Gi limits the reach of cAMP produced by β2ARs (see section 4.2). However, inhibition of Gi signaling with pertussis toxin does not enable EPR activation to regulate LTCCs [31].

4.2 G Proteins

The original collision coupling model assumes signaling proteins diffuse randomly throughout the membrane, interacting only briefly [53]. However, Rodbell and coworkers provided early evidence that G proteins are actually part of larger signaling complexes [54]. Immunoprecipitation experiments have shown that CaV1.2 is part of a macromolecular signaling complex that includes Gs [41, 44]. Although antibodies to CaV1.2 did not pull down Gi, they did demonstrate an interaction with caveolin-3, which is the muscle specific caveolin typically associated with the formation of caveolae (see section 6). Caveolin-3 in turn was found to associate with Gi. The molecular basis for these G protein interactions is not yet known, but the functional significance is reflected by the important effects that both Gs and Gi coupled receptors have on CaV1.2 function. One of the best studied example involves β2AR regulation of the LTCC. β2ARs can couple not only to Gs but also to Gi [34]. The β2AR can thus limit cAMP production by inhibiting AC through its ability activate Gi. This mechanism appears to be an effective means of spatially restricting cAMP production and PKA-dependent regulation of various target proteins, including CaV1.2 in cardiac myocytes [35, 36, 55, 56]. This was demonstrated by Chen-Izu et al. (63), who reported that blocking Gi signaling with pertussis toxin resulted in the ability of LTCCs to be regulated by distal as well as local β 2ARs (see section 4.1.1). It has also been demonstrated that β1ARs can couple to Gi as well as Gs following protein kinase C (PKC) activation [57], although the effect this has on the spatial distribution of cAMP production following stimulation of this receptor is unknown.

4.3 Adenylyl Cyclase

A CaV1.2/PKA signaling complex that includes a GPCR and the G protein through which it acts is not sufficient to produce spatially restricted cAMP dependent responses such as those associated with βAR stimulation. Inclusion of AC is also a critical factor. Balijepalli et al. [44] found that immunoprecipitation of CaV1.2 pulled down AC5/6 in addition to β2AR, Gs and PKA. Although the mechanism for the interaction between CaV1.2 and AC5/6 was not determined, Bauman et al. [58] used a heterologous expression system to demonstrate that AKAP5 (human AKAP79 or rodent AKAP150) is able to anchor PKA directly to both AC5 and AC6 [58, 59], the predominant isoforms in the heart [60]. It was subsequently shown that AKAP9 (Yotiao), is associated with AC activity in cardiac tissue, although it did not bind AC5 or AC6 [61]. AKAP6 (mAKAP or AKAP100), on the other hand, was found to selectively bind AC5 in cardiac myocytes, anchoring it to RyR2 [62]. However, the work of Nichols et al. [46] demonstrated that AKAP5 anchors AC5/6 to a signaling complex in cardiac myocytes that includes CaV1.2. They reported that the interaction of AKAP5 and AC5/6 with CaV1.2 was not direct, but instead via caveolin-3, which also binds a subset of CaV1.2 channels (see section 5). Through this interaction, βAR stimulation was found to preferentially phosphorylate CaV1.2 channels specifically associated with caveolin-3.

4.4 Phosphodiesterases

Hydrolysis of cAMP by PDEs can also play a critical role in restricting the effective radius of cAMP signaling and LTCC regulation in cardiac myocytes [63, 64]. Jurevicius et al. [65] elegantly demonstrated this by recording macroscopic currents generated by LTCCs at one end of an intact frog ventricular myocyte while activating βARs in either the same end (locally) or the opposite end (distally). Under normal conditions, LTCC activity was only affected by activating local βARs. However, stimulation of distal βARs was able to regulate LTCCs when PDE activity was inhibited. It should be noted that LTCC responses in the frog heart are mediated exclusively by β2ARs [66]. This suggests that PDE activity is responsible for ensuring that β2AR cAMP production affects only local LTCC function. It has been hypothesized that β2AR stimulation can stimulate PDE activity via Gi-dependent regulation of phosphoinositide 3 kinase γ (PI3Kγ) and that this is responsible for spatially restricting the effect of β2AR effects on LTCC function [67]. However, there is some controversy over what PDE isoforms are regulated by PI3Kγ in the heart and whether or not it affects LTCC activity [68].

The common perception is that PDEs restrict cAMP movement by acting as functional barriers to diffusion. However, computational models of cAMP signaling in cardiac myocytes suggest that this is not the case. Assuming that cAMP is able to diffuse at rates equivalent to free diffusion, PDE activity alone is not sufficient to create a gradient [48, 69]. However, if one assumes that cAMP diffusion is limited by some other mechanism, non-uniform distribution of PDEs can contribute to the generation of gradients by regulating the activity of cAMP degradation within a microdomain.

At least four different PDE families are involved in cAMP metabolism in mammalian cardiac tissue, PDE1, PDE2, PDE3, and PDE4, with each subtype represented by multiple genes products [64]. Furthermore, the relative level of expression of each isoform varies considerably among species, as does the apparent distribution between membrane and cytosolic fractions. PDE2, PDE3, and PDE4 isoforms contribute to spatially restricted cAMP signaling in cardiac myocytes [63, 64]. Furthermore, different Gs coupled receptors that stimulate LTCC activity exhibit differences in sensitivity to inhibition of PDE3 and/or PDE4 [30]. This implies that different PDEs may be associated with specific receptors as well as specific subpopulations of CaV1.2. Consistent with this idea, upon heterologous expression, different PDE4D isoforms can be recruited to β2AR via β-arrestin following receptor activation [70, 71]. It is not known whether β-arrestin also associates with the β2AR in the CaV1.2 complex in the heart, but if so, this mechanism could further contribute to the spatiotemporal restriction of cAMP signaling in the vicinity of such a complex. De Arcangelis et al. [72] demonstrated that various PDE4D isoforms are able to interact with the β2AR in neonatal ventricular myocytes. Furthermore, specific inhibition of PDE4D8 and PDE4D9 was found to enhance βAR stimulation of the spontaneous contraction rate in these cells. However, it is unclear what role if any regulation of LTCC activity plays in these responses.

Association with AKAPs is another means of achieving PDE localization [3]. The PDE4D3 isoform can be recruited to various subcellular compartments by directly or indirectly binding to AKAP6 [73, 74], AKAP9 (AKAP350) [75], and AKAP12 (gravin or AKAP250) [76]. These AKAPs act in part to assemble PKA and PDE4D into a complex in which localized phosphorylation of PDE4D by PKA results in its stimulation [73, 77].

PDE4B and PDE4D are also part of a signaling complex with CaV1.2 in mouse ventricular myocytes [78]. Whether or not this interaction is direct or perhaps involves an AKAP was not determined. However, βAR stimulation of LTCC activity was only enhanced in myocytes from PDE4B knockout animals. On the other hand, βAR stimulation of intracellular Ca2+ transients and myocyte contraction were enhanced in both PDE4B and PDE4D knockout mice. This is consistent with the idea that PDE4D is part of the RyR2 signaling complex [79].

4.5 Protein Kinases

4.5.1 Protein Kinase A

The role of PKA-dependent phosphorylation in regulation of cardiac LTCCs was first established over thirty years ago [28, 80]. Subsequent biochemical studies suggested the C terminus of the α11.2 subunit as the likely location of PKA-dependent phosphorylation. This was supported by work reporting that the truncated or α11.2 short form is not phosphorylated in vitro [81]. Furthermore, deletion of the α11.2 DCT has also been reported to cause a loss of β-adrenergic regulation [82]. However, the small size of the current observed in myocytes from transgenic animals expressing the truncated channel protein could have potentially obscured the ability to observe a PKA-dependent response. Early on, serine-1928 in the DCT was identified as the main target for PKA-dependent phosphorylation in vitro [15, 83] (Fig. 1). Such observations led to speculation that phosphorylation of this residue releases the autoinhibitory effect that the DCT has on the rest of the channel [1]. In support of this idea, both C-terminal truncation of α11.2 and phosphorylation by PKA produce a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage-dependence of channel gating [9, 11–13, 84, 85]. C-terminal truncation and PKA phosphorylation also have effects on modal gating of the channel (see section 4.6) [86, 87]. However, difficulties in reliably and reproducibly reconstituting regulation of Cav1.2 in heterologous expression systems left doubt about the role of serine-1928 [7, 13, 88, 89]. It has been suggested that in exogenous expressions systems, differences in basal phosphorylation might have preempted subsequent stimulatory responses in some studies, which could explain the inconsistencies [1]. However, the role that this residue plays was brought further into question by Ganesan et al. [90], who used an endogenous expression system to conclude that serine-1928 is not essential for PKA-mediated stimulation of CaV1.2 activity. They found that in cardiac myocytes in which native LTCC activity was inhibited, expression an α11.2 subunit in which serine-1928 was mutated to an alanine produced a Ca2+ current that was still sensitive to βAR stimulation. Perhaps the most definitive test for the role of serine-1928 phosphorylation was provided by Lemke et al. [91], who mutated serine-1928 to alanine in knock-in mice and found that stimulation of the LTCC current by the βAR agonist isoproterenol or the AC agonist forskolin was unaffected.

More recently, Fuller et al. [92] provided new evidence supporting the idea that PKA-dependent phosphorylation does indeed regulate CaV1.2 channel function by interfering with the autoinhibitory effect of the DCT fragment. But rather than involving serine-1928, they found that it actually requires phosphorylation of serine-1700, which is located in the proximal C-terminus of the truncated α11.2 subunit where it interfaces with the DCT peptide (Fig. 1). A key to reconstitution was found to be careful titration of AKAP expression. However, these studies were conducted using the truncated α11.2 subunit expressed together with a separate DCT fragment. Whether or not phosphorylation of serine-1700 plays a similar role in regulating the uncleaved α11.2 subunit has not been determined. Previous studies have demonstrated that mutation of serine-1928 in the full length subunit prevents PKA-dependent regulation [93, 94]. It is conceivable that the presence of both cleaved and uncleaved forms of the channel found in native cardiac myocytes could obfuscate the potential role of serine-1928, especially in light of evidence that LTCCs exist as oligomers [95].

Evidence that PKA phosphorylates at least one β subunit isoform has also led some to hypothesize that CaV1.2 regulation requires coexpression of α11.2 and β subunits [96, 97]. It was reported that PKA can phosphorylate serines-459, -478, and -479 of the cardiac β2 subunit splice variant β2a [98]. Mutating serines-478 and -479, but not -459, to alanines was reported to eliminate current stimulation by PKA [96]. However, even though serines-478 and -479 are conserved in most other β2 splice variants, they are absent in β1, β3, and β4 subunits. Therefore, because α11.2 can interact with several different β subunits [14, 99] and not all have corresponding phosphorylation sites, the role that β subunits may play PKA dependent regulation of LTCCs remains uncertain [100]. In fact, Brandmayr et al. [101] used transgenic mouse models to demonstrate that deletion of the C terminal portion of the β2 subunit, which contains the putative phosphorylation sites, did not alter the ability of βAR stimulation to regulate LTCC activity.

It has also been suggested that PKA-dependent phosphorylation of ahnak, a 700-kDa protein that is reported to bind CaV1.2 β2 subunits, may explain how channel activity is regulated [102]. It has been hypothesized that ahnak prevents the β2 subunit from interacting with α11.2, but following ahnak phosphorylation the β2 and α11.2 subunits are then able to come together, causing an increase in CaV1.2 current.

4.5.2 Protein Kinase C

Activation of PKC via Gq linked α1-adrenergic, endothelin, or angiotensin receptors has been reported to stimulate, inhibit, or both stimulate and inhibit LTCC activity in the heart [7, 103]. PKC has been reported to inhibit cloned CaV1.2 channels consisting of α11.2, β1b, and α2δ1 by phosphorylating threonine residues -27 and -31 in the amino terminus [104]. The mechanism for PKC stimulation of cardiac LTCC function is less clear. While it has been shown that serine-1928 can be phosphorylated by PKC [105], this is much less prominent than PKA phosphorylation of that residue [106]. Evidence suggests that at least some of the PKC effects on LTCC function involve recruitment of the enzyme to adaptor proteins known as receptors for activated C kinse (RACKs) [107]. However, PKC has also been shown to interact directly with α11.2 [105] as well as indirectly through AKAP5 [108].

4.6 Protein Phosphatases

Phosphatases are necessary to ensure the reversibility of kinase dependent phosphorylation. Perhaps the first evidence that phosphatases are part of a signaling complex associated with cardiac LTCCs came from electrophysiological studies looking at the effect of phosphatase inhibitors on rundown or spontaneous loss of single channel activity recorded in isolated patches of membrane. Ono and Fozzard demonstrated that rundown could be reversed by exposure of the intracellular surface of the membrane patch to the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid [109]. Okadaic acid also increases currents through cardiac LTCCs reconstituted in planar lipid bilayers [110]. Several pieces of evidence indicate that protein phosphatase type 2A (PP2A) and in some systems type 1 (PP1) are involved in reversing the effects PKA phosphorylation has on LTCCs [88]. For example, purified PP1 and PP2A inhibit whole cell LTCC currents that have been upregulated by βAR stimulation in isolated cardiac myocytes [111, 112]. Conversely, inhibition of PP1 and PP2A reverse or prevent PKA-mediated increases in LTCC currents [113, 114].

A more detailed analysis has provided some evidence for the idea that PP1 and PP2A differentially regulate different modes of channel gating, suggesting that there may be more than one phosphorylation site regulating LTCC activity. As discussed above, CaV1.2 exhibits modal gating: in mode 0 the channel open probability is near zero, in mode 1 the channel exhibits an increase in open probability due to bursts of brief openings, and in mode 2 the channel exhibits very long openings [115]. β-Adrenergic stimulation induces a switch from mode 0 to modes 1 and 2 [87]. Experiments using different inhibitors suggest PP1 and PP2A may be specific for regulating the transition between these different modes of gating [115, 116].

These observations suggest that a phosphatase is closely associated with Cav1.2. In fact, PP2A coimmunoprecipitates with CaV1.2 in neuronal preparations and reverses PKA-mediated phosphorylation of serine-1928 on α11.2 [117]. PP2A actually binds to two regions of the α11.2 subunit: residues 1795–1818 and 1965–1971 [118, 119].

Initial studies did not indicate that inhibition of protein phosphatase type 2B (PP2B or calcineurin) had any effect on LTCC currents in cardiac myocytes [114, 120] or neurons [121]. However, more recent work shows that PP2B regulates CaV1.2 activity in cardiac, neuronal, and smooth muscle cells [94, 122, 123]. AKAP5 recruits PP2B to CaV1.2 in neurons [94], and PP2B coimmunoprecipitates with CaV1.2 in cardiac myocytes [46, 123]. Furthermore, PP2B binds to the N and C-termini of the α11.2 subunit [123]. At the C terminus, the interaction involves residues 1943–1971, which are adjacent to the phosphorylation site at serine-1928 [118, 123]. Whereas this direct interaction is readily detectable by co-immunoprecipitation, the AKAP5-mediated interaction is not, as detergent used to solubilize CaV1.2 disrupts the AKAP5-PP2B interaction (Patriarchi and Hell, unpublished observation). Interestingly, even though PP2B was able to dephosphorylate CaV1.2, expression of a constitutively active form of the phosphatase actually increased the size of the endogenous LTCC current [123], which is different from the inhibitory action of AKAP5-anchored PP2B reported for neuronal CaV1.2 [94]. PP2B bound to the C-terminus of α11.2 might dephosphorylate a site of an unidentified kinase that otherwise inhibits channel activity whereas AKAP5-anchored PP2B likely acts by dephosphorylating stimulatory PKA sites.

The demonstration that CaV1.2 is part of a signaling complex that includes more than one type of phosphatase supports the idea that multiple phosphorylation sites, both stimulatory and inhibitory, are involved in regulating LTCC activity.

5. A Kinase Anchoring Proteins

PKA is an inactive tetramer consisting of two regulatory (inhibitory) (R) and two catalytic (C) subunits. Distinct genes encode four R (RIα, β and RIIα, β) and three C subunits (Cα, β, and γ). Suppression of C subunit catalytic activity is released following the binding of two molecules of cAMP to each R subunit [124]. It is now widely accepted that AKAPs play an essential role in orchestrating many different cAMP-dependent signaling events by tethering PKA and other regulatory enzymes together to form signaling complexes [125, 126]. PKA binding to AKAPs involves an amphipathic α helix that binds RII and in some cases RI dimers [127–129]. AKAPs, in turn, are recruited to specific subcellular locations through lipid membrane interactions or specific interaction with other proteins [130–132]. At least forty-three AKAP family members have been identified, with multiple isoforms generated by alternative splicing [132]. Many AKAPs were originally named based on their apparent molecular weight. This nomenclature has led to complications due to variations in electrophoretic mobility of different orthologs. In this review, we refer to AKAPs by their gene name, giving their other common names in parentheses.

At the time when there were inconsistencies in the ability to reconstitute PKA-dependent regulation of CaV1.2 channel function in heterologous expression systems, it had already been shown that AKAPs were necessary for PKA regulation of other types of ion channels in different systems [1]. Based on such observations, Hosey and colleagues [93] suggested that this might also be true for PKA-dependent regulation of cardiac LTCCs. Consistent with this idea, they reported that α11.2 could be phosphorylated by PKA in HEK293 cells stably expressing wild type AKAP5 (human AKAP79, rodent AKAP150), but not an AKAP5 mutant unable to bind PKA. They also demonstrated that Ht31, a peptide derived from the AKAP RII docking site that disrupts PKA binding [133], blocked PKA-dependent regulation of LTCC in native cardiac myocytes. In neurons, it has been shown that AKAP5 binds to three different sites on α 11.2 (Fig. 1) [134]. Although this AKAP was thought to be absent or in low abundance in the heart, recent studies clearly show its presence [1, 46]

The first AKAP found to be associated with CaV1.2 was the microtubule associated protein MAP2B [106]. However, MAP2B is expressed primarily in nerve tissue. On the other hand, Hulme et al. [135] demonstrated that AKAP7 (AKAP15 or AKAP18) is abundant in heart, where it coimmunoprecipitates and colocalizes with Cav1.2. Furthermore, it had been shown that PKA-dependent regulation of CaV1.2 currents could be reconstituted in HEK293 cells in the presence but not the absence of AKAP7 [131]. Finally, a peptide derived from the LZ-like motif that mediates AKAP7 binding to CaV1.2 was found to block β-adrenergic stimulation of L-type Ca2+ currents in native cardiac myocytes [135]. However, it is important to keep in mind that this peptide could also have displaced AKAPs other than AKAP7.

The above results suggest that both AKAP5 and AKAP7 play a role in regulating LTCC in cardiac myocytes. If this is true, the question remains as to how preventing the interaction of either one of these AKAPs alone was able to completely block PKA-dependent stimulation of the current in native myocytes. Part of the answer may lie in the fact that there is overlap in the docking sites. In fact one of the AKAP5 binding sites on α11.2 overlaps with the leucine zipper (LZ)-like motif that anchors AKAP7 [94, 134, 135] (Fig. 1).

More recently, Nichols et al. [46] examined the role of AKAP5 in sympathetic regulation of cardiac LTCC function using a knockout mouse model. They found that in the absence of this AKAP, the ability of β-adrenergic stimulation to enhance cytosolic Ca2+ transients in cardiac myocytes was blocked. Yet, unexpectedly, β-adrenergic stimulation of the LTCC current appeared to remain intact. This suggested that AKAP5 is not essential for regulation of cardiac LTCC activity. However, biochemical analysis using serine-1928 as a “readout” revealed that in wild type animals, β-adrenergic stimulation only led to phosphorylation of the subpopulation of LTCCs associated with caveolin-3, but in knockout animals β-stimulation preferentially phosphorylated those LTCCs not associated with caveolin-3. According to their results, AKAP5 targets AC, PP2B and PKA to a signaling complex associated with caveolin-3, which includes a subset of CaV1.2 (Fig. 2B). This facilitates the localized production of cAMP necessary for PKA-dependent phosphorylation of CaV1.2 associated with caveolin-3 as well as the SR proteins RyR2 and phospholamban. The authors suggest that in the absence of AKAP5, AC is redistributed to where it can contribute to βAR regulation of LTCCs not associated with caveolin-3, but regulation of RyR2 and phospholamban is lost. The authors also demonstrated that deleting the PKA binding domain of AKAP5 did not affect the ability of βAR stimulation to enhance Ca2+ transients. This finding suggests that PKA must be anchored to this signaling complex by other means as well. One possibility is through AKAP7, which has been reported to interact with the LZ-like domain on CaV1.2 [135]. However, it has recently been shown that PKA-dependent regulation of LTCC currents is intact in cardiac myocytes from AKAP7 knockout animals [136]. The fact that disrupting leucine zipper interactions blocks LTCC regulation suggests that some other leucine-zipper containing AKAP may be involved. Possible candidates include AKAP6 [137], AKAP9 [138], and AKAP13 (AKAP-Lbc) [139].

6. Lipid Rafts, Caveolae, and Cavoeolin-3

An alternative mechanism for the assembly of signaling complexes associated with CaV1.2 is through the colocalization of proteins in specific membrane domains [2]. The tight packing of sphingolipids and cholesterol in the plasma membrane creates microdomains called lipid rafts. These cholesterol rich domains can assemble signaling proteins with ion channels [140–142]. Proteins associated with lipid rafts are resistant to detergent (Triton X-100) solubilization and can be found in the low density membrane fractions obtained by sucrose density gradient centrifugation [143].

Caveolae are a morphologically distinct subset of lipid rafts that appear as 50–100 nm invaginations in the plasma membrane of many different cell types, including cardiac myocytes [140, 142, 144]. Caveolae are also specifically associated with the membrane protein caveolin [145]. There are three different types of caveolins: caveolin-1, -2, and -3. Caveolin-3 is sometimes referred to as the muscle specific caveolin, as it is found primarily (although not exclusively) in cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle. Caveolar proteins are typically associated with low density membrane fractions also containing caveolin-3. However, there is evidence that in cardiac myocytes not all caveolin-3 is associated with lipid rafts [146]. Some, but not all, CaV1.2 are present in caveolar fractions of the plasma membrane [44, 46, 147] along with varying amounts of other proteins associated with the cAMP/PKA signaling cascade. These include β1- and β 2ARs, AC5/6, Gs, Gi, PP2A, and the type II R subunit of PKA [32, 44, 46, 146, 148]. As described in previous sections of this review, many of these components of the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway have been tied to CaV1.2 via protein-protein interactions, either directly or indirectly. In some cases, the common connection may actually be through caveolin-3, by virtue of its caveolin scaffolding domain (CSD), which is a 20 amino acid sequence found in the membrane proximal N terminus [145, 149]. This may be important in forming signaling complexes in T-tubule membrane domains that are in close proximity to the junctional SR (Fig. 2B), where caveolae appear to be absent [150]. Another possibility is that some proteins are targeted to lipid rafts and caveolae by post-translational modifications such as myristoylation and/or palmitoylation. These include the β2AR, caveolins, G proteins, AKAP5, AKAP7, and the CaV1.2 β2a subunit [99, 151–155].

Cyclodextrins deplete membrane of cholesterol and disrupt caveolae [156] thereby altering responses associated with these signaling platforms [142]. Rybin et al. [148] first suggested that caveolae play a role in creating the local response associated with β 2ARs in cardiac myocytes. They found the majority of β2ARs in neonatal ventricular myocytes in caveolar membrane fractions and that disrupting caveolae by depleting membrane cholesterol enhanced cAMP production in response to β2AR activation. Cholesterol depletion enhanced the sensitivity of the LTCC response to β2AR stimulation [33], an effect similar to that produced by pertussis toxin block of Gi signaling, suggesting that caveolar signaling complexes are involved in Gi attenuation and localization of β2-adrenergic responses. The increase in sensitivity could also be due to disruption of the interaction between caveolin-3 and AC, which has an inhibitory effect on cyclase activity [148, 157].

Balijepalli et al. [44] demonstrated that caveolin-3, the β2AR, Gs, Gi, AC5/6, PKA, and CaV1.2 coimmunoprecipitate with each other. Furthermore, disruption of caveolae by cholesterol depletion or siRNA knockdown of caveolin-3 prevented β2-adrenergic stimulation of the LTCC current in neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes when Gi signaling was first blocked by pertussis toxin [44]. These observations indicate that caveolin-3 and more generally caveolae play some role in either the formation of the β 2AR-CaV1.2 complex or its colocalization with other signaling components.

Other studies have demonstrated that lipid rafts and/or caveolae are also important in β 1AR regulation of LTCCs. Agarwal et al. [32] found that cholesterol depletion enhanced β 1AR stimulation of LTCC function in adult cardiac myocytes. This correlated with the ability of cholesterol depletion to enhance cAMP signaling in microdomains associated specifically with type II PKA signaling as measured using FRET-based biosensors. Cholesterol depletion did not alter the β1AR sensitivity of global cAMP responses. The authors also demonstrated that cholesterol depletion had no effect on more global cAMP response produce by EPR activation. Those results correlated with the fact the β 1ARs were found in caveolar and non-caveolar fractions of the plasma membrane, while EPRs were only found in non-caveolar fractions [32], suggesting that PKA-dependent regulation of CaV1.2 involves localized production of cAMP by receptors in a signaling complex associated with caveolae/lipid rafts (Fig. 2A).

7. Summary

PKA-dependent phosphorylation plays an essential role in LTCC regulation. However, the exact mechanism for this regulatory effect is still an area of active investigation. Current evidence supports the idea that it may involve phosphorylation of one or more residues on α11.2, which then disrupts the autoinhibitory effect of the distal C terminal region of this subunit.

Another important aspect of LTCC regulation is the interaction of CaV1.2 with PKA. There is evidence that AKAP5 and AKAP7 can directly tether PKA to CaV1.2, while AKAP5 may also link PKA to CaV1.2 indirectly via caveolin-3. However, the precise roles of AKAP5 and AKAP7 have yet to be resolved. An intriguing possibility is that different AKAPs may be involved in regulating different subpopulations of LTCCs under different conditions and they can substitute for each other in corresponding KO animals.

In addition to PKA, regulation of CaV1.2 also depends on close association with AC and a GPCR. AKAPs appear to be important in targeting AC to CaV1.2 signaling complexes, while receptors such as the β2AR are physically linked to a subpopulation of CaV1.2 that is associated with caveolin-3. Evidence supporting a similar interaction between CaV1.2 and the β1AR is mixed. However, functional studies support the notion that at least some LTCCs are regulated via a localized cAMP response produced by β1ARs associated with lipid rafts. This highlights the potential importance of signaling complexes formed not only by protein-protein interactions, but also by colocalization of signaling proteins in specific membrane domains.

The fact that different receptors associated with cAMP production do not have the same effects on LTCC function is quite remarkable. EPRs produce cAMP without affecting channel function, β2ARs appear to affect only local channels, while β1ARs seem to affect both local and distal channels. The exact mechanism for this behavior is not well understood, but there is now evidence that this may involve the inclusion of PDEs as part of the CaV1.2 signaling complex.

Finally, reversal of PKA-dependent responses depends on phosphatase activity, and we now know that the CaV1.2 is actually capable of interacting with more than one type of phosphatase. This supports the interesting possibility that multiple phosphorylation sites are involved in regulating CaV1.2 activity.

In conclusion, rather than stochastically finding their targets, it is becoming increasingly clear that many, perhaps most, signaling proteins are linked in different ways to their ultimate targets, CaV1.2 being the prototypical one for ion channel regulation.

Highlights.

Ca2+ influx by L-type Ca2+ channels trigger Ca2+ release and cardiac contraction

We discuss how VGCC are regulated by GPCR via cAMP/PKA

VGCC form signaling complexes with β2AR, Gs, adenylyl cyclase, and PKA

VGCC also associate with the protein phosphatases PP2A and PP2B

These complexes regulate channel activity in a highly localized manner

Abbreviations

- LTCC

L-type Ca2+ channel

- βAR

β-adrenergic receptor

- EPR

E type prostaglandin receptor

- RyR2

type 2 ryanodine receptor

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- PP

protein phosphatase

- AKAP

A kinase anchoring protein

- PKA

protein kinase A

- DCT

distal C terminus

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- GPCR

G protein coupled receptor

- SERCA2a

type 2a sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase

- PLN

phospholamban

- CAV-3

caveolin-3

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: THE AUTHORS DECLARE THAT THERE IS NO CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dai S, Hall DD, Hell JW. Supramolecular assemblies and localized regulation of voltage-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:411–52. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Best JM, Kamp TJ. Different subcellular populations of L-type Ca2+ channels exhibit unique regulation and functional roles in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:376–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beene DL, Scott JD. A-kinase anchoring proteins take shape. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carafoli E. Calcium signaling: a tale for all seasons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1115–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032427999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 1995;80:259–68. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bers DM, Perez-Reyes E. Ca channels in cardiac myocytes: structure and function in Ca influx and intracellular Ca release. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:339–60. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao T, Cuadra AE, Ma H, Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Cheng T, et al. C-terminal fragments of the alpha 1C (CaV1. 2) subunit associate with and regulate L-type calcium channels containing C-terminal-truncated alpha 1C subunits. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21089–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao T, Puri TS, Gerhardstein BL, Chien AJ, Green RD, Hosey MM. Identification and subcellular localization of the subunits of L-type calcium channels and adenylyl cyclase in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19401–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerhardstein BL, Gao T, Bunemann M, Puri TS, Adair A, Ma H, et al. Proteolytic processing of the C terminus of the alpha(1C) subunit of L-type calcium channels and the role of a proline-rich domain in membrane tethering of proteolytic fragments. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8556–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulme JT, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Lin TW, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Autoinhibitory control of the CaV1. 2 channel by its proteolytically processed distal C-terminal domain. J Physiol. 2006;576:87–102. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikala G, Klockner U, Varadi M, Eisfeld J, Schwartz A, Varadi G. cAMP-dependent phosphorylation sites and macroscopic activity of recombinant cardiac L-type calcium channels. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;185:95–109. doi: 10.1023/a:1006878106672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei X, Perez-Reyes E, Lacerda AE, Schuster G, Brown AM, Birnbaumer L. Heterologous regulation of the cardiac Ca2+ channel α1 subunit by skeletal muscle β and gamma subunits. Implications for the structure of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21943–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Jongh KS, Murphy BJ, Colvin AA, Hell JW, Takahashi M, Catterall WA. Specific phosphorylation of a site in the full-length form of the alpha 1 subunit of the cardiac L-type calcium channel by adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Biochem. 1996;35:10392–402. doi: 10.1021/bi953023c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez-Ospina N, Tsuruta F, Barreto-Chang O, Hu L, Dolmetsch R. The C terminus of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel Ca(V)1. 2 encodes a transcription factor. Cell. 2006;127:591–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foell JD, Balijepalli RC, Delisle BP, Yunker AM, Robia SL, Walker JW, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of calcium channel beta-subunits in canine and human heart: evidence for differential subcellular localization. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:183–200. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00207.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singer D, Biel M, Lotan I, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F, Dascal N. The roles of the subunits in the function of the calcium channel. Science. 1991;253:1553–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1716787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamp TJ, Perez-Garcia MT, Marban E. Enhancement of ionic current and charge movement by coexpression of calcium channel beta 1A subunit with alpha 1C subunit in a human embryonic kidney cell line. J Physiol. 1996;492 (Pt 1):89–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chien AJ, Zhao X, Shirokov RE, Puri TS, Chang CF, Sun D, et al. Roles of a membrane-localized beta subunit in the formation and targeting of functional L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30036–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.30036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jay SD, Sharp AH, Kahl SD, Vedvick TS, Harpold MM, Campbell KP. Structural characterization of the dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel alpha 2-subunit and the associated delta peptides. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3287–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bangalore R, Mehrke G, Gingrich K, Hofmann F, Kass RS. Influence of L-type Ca channel alpha 2/delta-subunit on ionic and gating current in transiently transfected HEK 293 cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H1521–H1528. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolphin AC. Calcium channel auxiliary alpha(2)delta and beta subunits: trafficking and one step beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:542–55. doi: 10.1038/nrn3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L, Katchman A, Morrow JP, Doshi D, Marx SO. Cardiac L-type calcium channel (Cav1. 2) associates with gamma subunits. FASEB J. 2011;25:928–36. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-172353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antzelevitch C. Role of spatial dispersion of repolarization in inherited and acquired sudden cardiac death syndromes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2024–H2038. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00355.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, et al. Ca(V)1. 2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antzelevitch C, Pollevick GD, Cordeiro JM, Casis O, Sanguinetti MC, Aizawa Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cardiac calcium channel underlie a new clinical entity characterized by ST-segment elevation, short QT intervals, and sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2007;115:442–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reuter H. Calcium channel modulation by neurotransmitters, enzymes and drugs. Nature. 1983;301:569–74. doi: 10.1038/301569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levitzki A. From epinephrine to cyclic AMP. Science. 1988;241:800–5. doi: 10.1126/science.2841758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rochais F, bi-Gerges A, Horner K, Lefebvre F, Cooper DM, Conti M, et al. A specific pattern of phosphodiesterases controls the cAMP signals generated by different Gs-coupled receptors in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;98:1081–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218493.09370.8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warrier S, Ramamurthy G, Eckert RL, Nikolaev VO, Lohse MJ, Harvey RD. cAMP microdomains and L-type Ca2+ channel regulation in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2007;580:765–76. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal SR, Macdougall DA, Tyser R, Pugh SD, Calaghan SC, Harvey RD. Effects of cholesterol depletion on compartmentalized cAMP responses in adult cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:500–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calaghan S, White E. Caveolae modulate excitation-contraction coupling and beta2-adrenergic signalling in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:816–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao RP, Zhu W, Zheng M, Chakir K, Bond R, Lakatta EG, et al. Subtype-specific beta-adrenoceptor signaling pathways in the heart and their potential clinical implications. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:358–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao RP, Hohl C, Altschuld R, Jones L, Livingston B, Ziman B, et al. Beta 2-adrenergic receptor-stimulated increase in cAMP in rat heart cells is not coupled to changes in Ca2+ dynamics, contractility, or phospholamban phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19151–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao RP, Lakatta EG. Beta 1-adrenoceptor stimulation and beta 2-adrenoceptor stimulation differ in their effects on contraction, cytosolic Ca2+, and Ca2+ current in single rat ventricular cells. Circ Res. 1993;73:286–300. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altschuld RA, Starling RC, Hamlin RL, Billman GE, Hensley J, Castillo L, et al. Response of failing canine and human heart cells to β2- adrenergic stimulation. Circulation. 1995;92:1612–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.6.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuschel M, Zhou YY, Spurgeon HA, Bartel S, Karczewski P, Zhang SJ, et al. Beta2-adrenergic cAMP signaling is uncoupled from phosphorylation of cytoplasmic proteins in canine heart. Circulation. 1999;99:2458–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calaghan S, Kozera L, White E. Compartmentalisation of cAMP-dependent signalling by caveolae in the adult cardiac myocyte. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen-Izu Y, Xiao RP, Izu LT, Cheng H, Kuschel M, Spurgeon H, et al. G(i)-dependent localization of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor signaling to L-type Ca(2+) channels. Biophys J. 2000;79:2547–56. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76495-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davare MA, Avdonin V, Hall DD, Peden EM, Burette A, Weinberg RJ, et al. A beta2 adrenergic receptor signaling complex assembled with the Ca2+ channel Cav1. 2. Science. 2001;293:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5527.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macdougall DA, Agarwal SR, Stopford EA, Chu H, Collins JA, Longster AL, et al. Caveolae compartmentalise beta2-adrenoceptor signals by curtailing cAMP production and maintaining phosphatase activity in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of the adult ventricular myocyte. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:388–400. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nikolaev VO, Moshkov A, Lyon AR, Miragoli M, Novak P, Paur H, et al. Beta2-adrenergic receptor redistribution in heart failure changes cAMP compartmentation. Science. 2010;327:1653–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1185988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balijepalli RC, Foell JD, Hall DD, Hell JW, Kamp TJ. Localization of cardiac L-type Ca(2+) channels to a caveolar macromolecular signaling complex is required for beta(2)-adrenergic regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7500–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503465103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qian H, Matt L, Zhang M, Nguyen M, Patriarchi T, Koval OM, et al. beta2-Adrenergic receptor supports prolonged theta tetanus-induced LTP. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:2703–12. doi: 10.1152/jn.00374.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nichols CB, Rossow CF, Navedo MF, Westenbroek RE, Catterall WA, Santana LF, et al. Sympathetic stimulation of adult cardiomyocytes requires association of AKAP5 with a subpopulation of L-type calcium channels. Circ Res. 2010;107:747–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayes JS, Brunton LL, Mayer SE. Selective activation of particulate cAMP-dependent protein kinase by isoproterenol and prostaglandin E1. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:5113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saucerman JJ, Zhang J, Martin JC, Peng LX, Stenbit AE, Tsien RY, et al. Systems analysis of PKA-mediated phosphorylation gradients in live cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12923–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600137103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Benedetto G, Zoccarato A, Lissandron V, Terrin A, Li X, Houslay MD, et al. Protein kinase A type I and type II define distinct intracellular signaling compartments. Circ Res. 2008;103:836–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.174813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buxton IL, Brunton LL. Compartments of cyclic AMP and protein kinase in mammalian cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:10233–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warrier S, Belevych AE, Ruse M, Eckert RL, Zaccolo M, Pozzan T, et al. Beta-adrenergic and muscarinic receptor induced changes in cAMP activity in adult cardiac myocytes detected using a FRET based biosensor. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:C455–C461. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00058.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu S, Li Y, Kim S, Fu Q, Parikh D, Sridhar B, et al. Phosphodiesterases coordinate cAMP propagation induced by two stimulatory G protein-coupled receptors in hearts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6578–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117862109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tolkovsky AM, Levitzki A. Theories and predictions of models describing sequential interactions between the receptor, the GTP regulatory unit, and the catalytic unit of hormone dependent adenylate cyclases. J Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1981;7:139–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schlegel W, Kempner ES, Rodbell M. Activation of adenylate cyclase in hepatic membranes involves interactions of the catalytic unit with multimeric complexes of regulatory proteins. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:5168–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuschel M, Zhou YY, Cheng H, Zhang SJ, Chen Y, Lakatta EG, et al. G(i) protein-mediated functional compartmentalization of cardiac beta(2)-adrenergic signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22048–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou YY, Cheng H, Bogdanov KY, Hohl C, Altschuld R, Lakatta EG, et al. Localized cAMP-dependent signaling mediates beta 2-adrenergic modulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1611–H1618. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belevych AE, Juranek I, Harvey RD. Protein kinase C regulates functional coupling of beta1-adrenergic receptors to Gi/o-mediated responses in cardiac myocytes. FASEB J. 2004;18:367–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0647fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bauman AL, Soughayer J, Nguyen BT, Willoughby D, Carnegie GK, Wong W, et al. Dynamic regulation of cAMP synthesis through anchored PKA-adenylyl cyclase V/VI complexes. Mol Cell. 2006;23:925–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Efendiev R, Samelson BK, Nguyen BT, Phatarpekar PV, Baameur F, Scott JD, et al. AKAP79 interacts with multiple adenylyl cyclase (AC) isoforms and scaffolds AC5 and -6 to alpha-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate (AMPA) receptors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14450–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ishikawa Y, Homcy CJ. The adenylyl cyclases as integrators of transmembrane signal transduction. Circ Res. 1997;80:297–304. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piggott LA, Bauman AL, Scott JD, Dessauer CW. The A-kinase anchoring protein Yotiao binds and regulates adenylyl cyclase in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13835–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kapiloff MS, Piggott LA, Sadana R, Li J, Heredia LA, Henson E, et al. An adenylyl cyclase-mAKAPbeta signaling complex regulates cAMP levels in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23540–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.030072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischmeister R, Castro LR, bi-Gerges A, Rochais F, Jurevicius J, Leroy J, et al. Compartmentation of cyclic nucleotide signaling in the heart: the role of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Circ Res. 2006;99:816–28. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000246118.98832.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mika D, Leroy J, Vandecasteele G, Fischmeister R. PDEs create local domains of cAMP signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jurevicius J, Fischmeister R. cAMP compartmentation is responsible for a local activation of cardiac Ca2+ channels by β-adrenergic agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:295–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skeberdis VA, Jurevicius J, Fischmeister R. Beta-2 adrenergic activation of L-type Ca++ current in cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:452–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marcantoni A, Levi RC, Gallo MP, Hirsch E, Alloatti G. Phosphoinositide 3-kinasegamma (PI3Kgamma) controls L-type calcium current (ICa,L) through its positive modulation of type-3 phosphodiesterase (PDE3) J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:329–36. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kerfant BG, Zhao D, Lorenzen-Schmidt I, Wilson LS, Cai S, Chen SR, et al. PI3Kgamma is required for PDE4, not PDE3, activity in subcellular microdomains containing the sarcoplasmic reticular calcium ATPase in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2007;101:400–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iancu RV, Jones SW, Harvey RD. Compartmentation of cAMP signaling in cardiac myocytes: a computational study. Biophys J. 2007;92:3317–31. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.095356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baillie GS, Sood A, McPhee I, Gall I, Perry SJ, Lefkowitz RJ, et al. beta-Arrestin-mediated PDE4 cAMP phosphodiesterase recruitment regulates beta-adrenoceptor switching from Gs to Gi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:940–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262787199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 71.Perry SJ, Baillie GS, Kohout TA, McPhee I, Magiera MM, Ang KL, et al. Targeting of cyclic AMP degradation to beta 2-adrenergic receptors by beta-arrestins. Science. 2002;298:834–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1074683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De AV, Liu R, Soto D, Xiang Y. Differential association of phosphodiesterase 4D isoforms with beta2-adrenoceptor in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33824–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dodge-Kafka KL, Soughayer J, Pare GC, Carlisle Michel JJ, Langeberg LK, Kapiloff MS, et al. The protein kinase A anchoring protein mAKAP coordinates two integrated cAMP effector pathways. Nature. 2005;437:574–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dodge KL, Khouangsathiene S, Kapiloff MS, Mouton R, Hill EV, Houslay MD, et al. mAKAP assembles a protein kinase A/PDE4 phosphodiesterase cAMP signaling module. EMBO J. 2001;20:1921–30. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tasken KA, Collas P, Kemmner WA, Witczak O, Conti M, Tasken K. Phosphodiesterase 4D and protein kinase a type II constitute a signaling unit in the centrosomal area. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21999–2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Willoughby D, Wong W, Schaack J, Scott JD, Cooper DM. An anchored PKA and PDE4 complex regulates subplasmalemmal cAMP dynamics. EMBO J. 2006;25:2051–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Conti M, Richter W, Mehats C, Livera G, Park JY, Jin C. Cyclic AMP-specific PDE4 phosphodiesterases as critical components of cyclic AMP signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5493–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leroy J, Richter W, Mika D, Castro LR, Abi-Gerges A, Xie M, et al. Phosphodiesterase 4B in the cardiac L-type Ca(2)(+) channel complex regulates Ca(2)(+) current and protects against ventricular arrhythmias in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2651–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI44747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lehnart SE, Wehrens XH, Reiken S, Warrier S, Belevych AE, Harvey RD, et al. Phosphodiesterase 4D deficiency in the ryanodine-receptor complex promotes heart failure and arrhythmias. Cell. 2005;123:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Osterrieder W, Brum G, Hescheler W, Trautwein W, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. Injection of subunits of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase into cardiac myocytes modulates Ca+2 current. Nature. 1982;298:576–8. doi: 10.1038/298576a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yoshida A, Takahashi M, Nishimura S, Takeshima H, Kokubun S. Cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation and regulation of the cardiac dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca channel. FEBS Lett. 1992;309:343–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80804-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fu Y, Westenbroek RE, Yu FH, Clark JP, III, Marshall MR, Scheuer T, et al. Deletion of the distal C terminus of CaV1. 2 channels leads to loss of beta-adrenergic regulation and heart failure in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12617–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mitterdorfer J, Froschmayr M, Grabner M, Moebius FF, Glossmann H, Striessnig J. Identification of PK-A phosphorylation sites in the carboxyl terminus of L-type calcium channel alpha 1 subunits. Biochem. 1996;35:9400–6. doi: 10.1021/bi960683o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hulme JT, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Phosphorylation of serine 1928 in the distal C-terminal domain of cardiac CaV1. 2 channels during beta1-adrenergic regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16574–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607294103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wei X, Neely A, Lacerda AE, Olcese R, Stefani E, Perez-Reyes E, et al. Modification of Ca2+ channel activity by deletions at the carboxyl terminus of the cardiac α1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1635–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hess P, Lansman JB, Tsien RW. Different modes of Ca channel gating behaviour favoured by dihydropyridine Ca agonists and antagonists. Nature. 1984;311:538–44. doi: 10.1038/311538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yue DT, Herzig S, Marban E. β-Adrenergic stimulation of calcium channels occurs by potentiation of high-activity gating modes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:753–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Herzig S, Neumann J. Effects of serine/threonine protein phosphatases on ion channels in excitable membranes. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:173–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zong X, Schreieck J, Mehrke G, Welling A, Schuster A, Bosse E, et al. On the regulation of the expressed L-type calcium channel by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:340–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00373908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ganesan AN, Maack C, Johns DC, Sidor A, O’Rourke B. Beta-adrenergic stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in cardiac myocytes requires the distal carboxyl terminus of alpha1C but not serine 1928. Circ Res. 2006;98:e11–e18. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202692.23001.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lemke T, Welling A, Christel CJ, Blaich A, Bernhard D, Lenhardt P, et al. Unchanged beta-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac L-type calcium channels in Ca v 1.2 phosphorylation site S1928A mutant mice. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34738–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804981200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fuller MD, Emrick MA, Sadilek M, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular mechanism of calcium channel regulation in the fight-or-flight response. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra70. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gao T, Yatani A, Dell’Acqua ML, Sako H, Green SA, Dascal N, et al. cAMP-dependent regulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels requires membrane targeting of PKA and phosphorylation of channel subunits. Neuron. 1997;19:185–96. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oliveria SF, Dell’Acqua ML, Sather WA. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron. 2007;55:261–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dixon RE, Yuan C, Cheng EP, Navedo MF, Santana LF. Ca2+ signaling amplification by oligomerization of L-type Cav1. 2 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1749–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116731109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Gao T, Hosey MM. Functional regulation of L-type calcium channels via protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of the beta(2) subunit. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33851–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Haase H, Karczewski P, Beckert R, Krause EG. Phosphorylation of the L-type calcium channel beta subunit is involved in beta-adrenergic signal transduction in canine myocardium. FEBS Lett. 1993;335:217–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80733-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gerhardstein BL, Puri TS, Chien AJ, Hosey MM. Identification of the sites phosphorylated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase on the beta 2 subunit of L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels. Biochem. 1999;38:10361–70. doi: 10.1021/bi990896o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dolphin AC. Beta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2003;35:599–620. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000008026.37790.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miriyala J, Nguyen T, Yue DT, Colecraft HM. Role of CaVbeta subunits, and lack of functional reserve, in protein kinase A modulation of cardiac CaV1. 2 channels. Circ Res. 2008;102:e54–e64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.171736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brandmayr J, Poomvanicha M, Domes K, Ding J, Blaich A, Wegener JW, et al. Deletion of the C-terminal Phosphorylation Sites in the Cardiac beta-Subunit Does Not Affect the Basic beta-Adrenergic Response of the Heart and the Cav1. 2 Channel. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22584–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.366484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Haase H, Alvarez J, Petzhold D, Doller A, Behlke J, Erdmann J, et al. Ahnak is critical for cardiac Ca(V)1. 2 calcium channel function and its beta-adrenergic regulation. FASEB J. 2005;19:1969–77. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3997com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kamp TJ, Hell JW. Regulation of cardiac L-type calcium channels by protein kinase A and protein kinase C. Circ Res. 2000;87:1095–102. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McHugh D, Sharp EM, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Inhibition of cardiac L-type calcium channels by protein kinase C phosphorylation of two sites in the N-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12334–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210384297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yang L, Liu G, Zakharov SI, Morrow JP, Rybin VO, Steinberg SF, et al. Ser1928 is a common site for Cav1. 2 phosphorylation by protein kinase C isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:207–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Davare MA, Dong F, Rubin CS, Hell JW. The A-kinase anchor protein MAP2B and cAMP-dependent protein kinase are associated with class C L-type calcium channels in neurons. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30280–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang ZH, Johnson JA, Chen L, El-Sherif N, Mochly-Rosen D, Boutjdir M. C2 region-derived peptides of p-protein kinase C regulate cardiac Ca2+ channels. Circ Res. 1997;80:720–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.5.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Klauck TM, Faux MC, Labudda K, Langeberg LK, Jaken S, Scott JD. Coordination of three signaling enzymes by AKAP79, a mammalian scaffold protein. Science. 1996;271:1589–92. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ono K, Fozzard HA. Phosphorylation restores activity of L-type calcium channels after rundown in inside-out patches from rabbit cardiac cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;454:673–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang Y, Townsend C, Rosenberg RL. Regulation of cardiac L-type Ca channels in planar lipid bilayers by G proteins and protein phosphorylation. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:C1473–C1479. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.6.C1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hescheler J, Kameyama M, Trautwein W, Mieskes G, Soling HD. Regulation of the cardiac calcium channel by protein phosphatases. Eur J Biochem. 1987;165:261–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kameyama M, Hescheler W, Mieskes G, Trautwein W. The protein-specific photophatase 1 antagonizes the beta- adrendergic increase of the cardiac Ca current. Pflügers Arch. 1986;407:461–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00652635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hartzell HC, Hirayama Y, Petit-Jacques J. Effects of protein phosphatase and kinase inhibitors on the cardiac L-type Ca current suggest two sites are phosphorylated by protein kinase A and another protein kinase. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:393–414. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Frace AM, Hartzell HC. Opposite effects of phosphatase inhibitors on L-type calcium and delayed rectifier currents in frog cardiac myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;472:305–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ono K, Fozzard HA. Two phosphatase sites on the Ca2+ channel affecting different kinetic functions. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;470:73–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wiechen K, Yue DT, Herzig S. Two distinct functional effects of protein phosphatase inhibitors on guinea-pig cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;484:583–92. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]