Abstract

Background: Plant-based and fiber-rich diets high in vegetables, fruit, and whole grains are recommended to prevent cancer and chronic conditions associated with renal cell carcinoma (RCC), such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. Diet may play a role in the etiology of RCC directly and/or indirectly.

Objective: In a large prospective cohort of US men and women, we comprehensively investigated dietary intake and food sources of fiber in relation to RCC risk.

Design: Participants of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study (n = 491,841) completed a self-administered questionnaire of demographics, diet, lifestyle, and medical history. Over 9 (mean) years of follow-up we identified 1816 incident cases of RCC. HRs and 95% CIs were estimated within quintiles by using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results: Total dietary fiber intake was associated with a significant 15–20% lower risk of RCC in the 2 highest quintiles compared with the lowest (P-trend = 0.005). Intakes of legumes, whole grains, and cruciferous vegetables were also associated with a 16–18% reduced risk of RCC. Conversely, refined grain intake was positively associated with RCC risk in a comparison of quintile 5 with quintile 1 (HR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.39; P-trend = 0.04). The inverse association between fiber intake and RCC was consistent among participants who never smoked, had a body mass index [BMI (in kg/m2)] <30, and did not report a history of diabetes or hypertension.

Conclusions: Intake of fiber and fiber-rich plant foods was associated with a significantly lower risk of RCC in this large US cohort. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00340015.

INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for nearly all cancers of the kidney in adults. Although relatively rare (diagnosis in 1 of 67 men and women during their lifetime), the age-adjusted incidence of RCC has been steadily increasing in the United States, doubling over the past 3 decades (1). This incidence is in accordance with the growing epidemic of obesity and hypertension, which along with smoking account for the most well-established risk factors for RCC (2). Surprisingly, the role of dietary factors is not well understood.

Plant-based and fiber-rich diets high in vegetables, fruit, and whole grains are recommended for the prevention of cancer and chronic conditions positively associated with RCC incidence, such as hypertension and diabetes (3, 4). Thus, diet may play a role in RCC etiology directly and/or indirectly. A pooled analysis of 13 prospective cohorts suggests that there may be great promise for fruit and vegetables in RCC prevention (5, 6), whereas the limited evidence from individual studies is not wholly consistent (7–10), and the mechanisms remain unclear. Beyond free radical scavenging antioxidants and phytochemicals, fiber is an important component of fruit and vegetables with a potential role in cancer prevention and body weight and blood glucose control (11). Dietary fiber also has the potential to lower RCC risk by reducing systemic and/or chronic inflammation (12–17). However, there are little prospective data for intake of fiber and other key food sources, such as whole grains and legumes, in relation to RCC risk.

In a large US cohort, we prospectively investigated the dietary intake of fiber and fiber-rich plant foods in relation to RCC risk. Because diet and lifestyle may modulate intermediate risk factors in RCC etiology, we further examined whether associations varied by BMI, history of hypertension or diabetes, and other major RCC risk factors.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study cohort

The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study is a large prospective cohort of US men and women aged 50–71 y residing in 6 states (California, Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania) and 2 metropolitan areas (Atlanta, GA, and Detroit, MI). At baseline in 1995–1996, participants completed a self-administered questionnaire of demographics, diet, and lifestyle; details of the study design were described previously (18). Of those who completed the baseline questionnaire satisfactorily (n = 566,399), we excluded proxy respondents (n = 15,760) and participants with prevalent cancer (as noted by cancer registry or self-report; n = 51,223) or end-stage renal disease (n = 997) at baseline, a mortality report only for any cancer (n = 2143), zero person-years of follow-up (n = 44), or extremely high (men: >6141 kcal; women: >4791 kcal) or low (men: <415 kcal; women: <318 kcal) total energy intake beyond twice the IQR of sex-specific Box-Cox transformed intake (19) (n = 4391). After exclusions, the baseline analytic cohort included 491,841 (n = 293,248 men; 198,593 women) participants. An additional questionnaire to collect further information on medical history and other risk factors was sent ∼6 mo after the baseline questionnaire; 302,162 participants (n = 176,179 men; 125,983 women) responded and met the inclusion criteria above (herein referred to as the “subcohort”). The conduct of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study was reviewed and approved by the Special Studies Institutional Review Board of the US National Cancer Institute, and all participants gave informed consent by virtue of completing and returning the questionnaire.

Dietary assessment

Participants were asked to report their usual dietary intake of foods and beverages over the past year in both frequency of intake and portion size in a 124-item food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) developed and validated by the National Cancer Institute (19, 20). Nutrient and total energy intakes were calculated by using the 1994–1996 US Department of Agriculture's Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (21, 22). The nutrient database for dietary fiber was informed by the method of the Association of Official Analytic Chemist (23). Fiber from grains, fruit, vegetables, and legumes (beans) were estimated by summing dietary fiber from all grains, all fruit, all vegetables, and all beans/legumes in the questionnaire, including mixed dishes, respectively. Food groups were created with the MyPyramid Equivalents Database version 1.0, which uses the corresponding recipe files to disaggregate food mixtures into their component ingredients, assign them to food groups, and calculate cup or ounce equivalents (24). For fruit and vegetables, a 1-cup equivalent (8 oz, 225 g, or 237 mL) is defined as 1 cup raw or cooked vegetables or fruit, 1 cup vegetable or fruit juice, 0.5 cups dried fruit, or 2 cups leafy salad greens (24). Legume cup equivalents are similarly defined as 1 cup cooked dry beans or peas. For the grain group, a 1-ounce equivalent (28 g) is defined as 1 regular slice of yeast bread; 0.5 cups rice, pasta, or cooked cereal; or 1 cup ready-to-eat cereal. We additionally investigated fruit and vegetable subgroups (eg, dark-green vegetables, orange vegetables, and starchy vegetables) and botanical families classified according to their phytochemical content and proposed mechanism of action (25). The FFQ was validated with 2 nonconsecutive 24-h dietary recalls in a subset of the cohort (19, 26). Energy-adjusted correlation coefficients in men and women, respectively, were 0.72 and 0.66 for dietary fiber intake and 0.72 and 0.61 for total fruit and vegetable intake.

Case ascertainment

Cancer cases were ascertained through linkage with the 8 original state cancer registries plus an additional 3 states (Arizona, Nevada, and Texas), to where participants commonly migrated. The cancer registries are certified by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries as being ≥90% complete within 2 y of cancer incidence. The validation of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health study case ascertainment methods are described in detail elsewhere (27). Follow-up for each subject began on the date of questionnaire return and continued until the date of cancer diagnosis, movement out of the registry area, death, or end of follow-up on 31 December 2006, whichever came first.

RCC endpoints were defined by anatomic site and histologic code by using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-0-3) (28). We restricted our definition of primary adenocarcinoma of the kidney (C649) to the following histology codes: 8140, 8141, 8190, 8200, 8211, 8251, 8255, 8260, 8270, 8280, 8310, 8312, 8316, 8320, 8323, 8370, 8440, 8450, 8480, 8481, 8490, 8500, 8504, 8510, 8521, 8550, 8570, 8940, and 8959. The 2 most common and distinctly defined histomorphologic subtypes of RCC were also investigated: clear cell (histology code 8310) and papillary (8260) adenocarcinomas (29). RCCs not otherwise specified were not included in the subtype analysis (histology code 8312) (29).

Statistical analysis

All dietary variables were adjusted for total energy intake by using the nutrient density method and are presented for ease of interpretability as grams or servings per 1000 kcal of total energy intake. Residual energy adjustment (30) produced similar results. We evaluated the association between fiber intake and fiber-rich plant food sources in relation to risk of RCC using Cox proportional hazards regression models with person-years as the underlying time metric. HRs, 95% CIs, and P values for linear trend (using the median value within quintiles) are reported across quintiles of intake with the lowest intake quintile representing the referent group. We also examined associations with continuous increments of intake (eg, 10 g/1000 kcal). We confirmed that the Cox proportional hazards assumption was met through assessment of interaction terms for the exposures with follow-up time. Multivariable models included the following covariates: age (modeled as a continuous covariate), sex, education (<8 y, 8–11 y, high school graduate, some college, or college graduate), marital status, family history of any cancer (first-degree relative), race [non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or other (Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaskan Native], BMI (<18.5, 18.5 to <25, 25 to <30, 30 to <35, ≥35; in kg/m2), smoking status (never, quit ≥10 y ago, quit 5–9 y ago, quit 1–4 y ago, quit <1 y ago or currently smoking and smoked ≤20 cigarettes/d, or quit <1 y ago or currently smoking and smoked >20 cigarettes/d), history of diabetes (yes or no), history of hypertension (yes or no), alcohol intake (none, 0 to <5, 5 to <15, 15 to <30, or ≥30 g/d), and red meat intake (g/1000 kcal; modeled in quintiles). Indicator variables were created for covariates with missing values (smoking status and personal history of hypertension). Exclusion of participants with missing values produced similar results. In the multivariable models, we also mutually adjusted for other dietary factors as appropriate (eg, fruit intake was adjusted for intake of vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, and vice versa). Physical activity was not strongly associated with RCC risk in this cohort (31, 32), and additional adjustment for activity levels did not materially change estimates in multivariable models.

We assessed whether associations varied by sex, histologic subtype, smoking status, race, BMI, history of hypertension or diabetes, or alcohol intake and conducted a lag analysis excluding the first 2 y of follow-up. We also assessed interactions with red meat intake, because we previously observed associations with RCC risk in this cohort (33). Statistical tests for interaction evaluated the significance of categorical cross-product terms in the multivariable-adjusted models. All statistical tests were 2-sided and were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

Over a mean follow-up of 9 y, we ascertained 1816 cases of RCC (n = 498 clear cell, n = 115 papillary cell, n = 1056 not otherwise specified, n = 147 otherwise specified). Participants in the highest compared with the lowest quintile of fiber intake were more likely to be never-smokers and college-educated and were less likely to be obese (Table 1). Participants with high fiber intake also tended to consume more fruit, vegetables, and legumes and less red meat than participants with low fiber intake.

TABLE 1.

Means and proportions for selected baseline characteristics of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study participants by total dietary fiber intake (n = 491,841)

| Quintile of dietary fiber intake |

|||||

| Characteristic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Fiber intake (g/1000 kcal) | 6.4 ± 0.0041 | 8.7 ± 0.002 | 10.4 ± 0.002 | 12.4 ± 0.003 | 16.8 ± 0.01 |

| Age (y) | 61.2 ± 0.02 | 61.8 ± 0.02 | 62.1 ± 0.02 | 62.4 ± 0.02 | 62.6 ± 0.02 |

| Male (%) | 59.6 | 59.6 | 59.6 | 59.6 | 59.6 |

| White, non-Hispanic (%) | 91.1 | 92.2 | 92.0 | 91.3 | 89.5 |

| Black, non-Hispanic (%) | 4.5 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 4.1 |

| Other race (%) | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 5.0 | 6.5 |

| College and postcollege (%) | 31.2 | 36.3 | 39.3 | 41.6 | 44.4 |

| Currently married (%) | 65.6 | 69.3 | 70.2 | 69.8 | 67.9 |

| Positive family history of cancer (%) | 48.1 | 49.0 | 49.1 | 49.0 | 48.0 |

| Never-smoker (%) | 27.4 | 33.5 | 36.5 | 38.4 | 40.1 |

| Current smoker or quit <1 y ago (%) | 26.8 | 15.8 | 11.4 | 8.4 | 5.9 |

| Alcohol intake (g) | 22.3 ± 0.16 | 15.1 ± 0.12 | 10.9 ± 0.09 | 7.9 ± 0.06 | 5.4 ± 0.04 |

| Obese, BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (%) | 24.4 | 23.8 | 22.2 | 20.3 | 16.8 |

| History of hypertension (%)2 | 43.6 | 43.6 | 43.3 | 43.5 | 42.5 |

| History of diabetes (%) | 6.7 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 10.6 |

| Daily dietary intake | |||||

| Fruit (servings/1000 kcal)3 | 0.7 ± 0.002 | 0.9 ± 0.002 | 1.1 ± 0.002 | 1.4 ± 0.002 | 1.8 ± 0.003 |

| Vegetables (servings/1000 kcal)34 | 0.7 ± 0.001 | 0.9 ± 0.001 | 1.1 ± 0.001 | 1.2 ± 0.002 | 1.7 ± 0.003 |

| Legumes (servings/1000 kcal)5 | 0.03 ± 0.0001 | 0.04 ± 0.0001 | 0.05 ± 0.0001 | 0.06 ± 0.0002 | 0.10 ± 0.0003 |

| Red meat (g/1000 kcal) | 43.9 ± 0.08 | 40.1 ± 0.07 | 36.0 ± 0.06 | 30.9 ± 0.06 | 21.9 ± 0.05 |

| Total energy (kcal) | 2012 ± 3.0 | 1934 ± 2.7 | 1837 ± 2.3 | 1749 ± 2.3 | 1642 ± 2.2 |

Mean ± SE (all such values).

Ascertained from a second questionnaire mailed within 6 mo of the baseline questionnaire.

MyPyramid Equivalents Database vegetables and fruit: 1 cup equivalent (8 oz, 225 g, or 237 mL) = 1 cup raw or cooked vegetable or fruit, 2 cups leafy salad greens, 1 cup vegetable or fruit juice, 0.5 cups dried fruit.

Does not include legumes.

MyPyramid Equivalents Database legumes: 1 cup equivalent = 1 cup cooked dried beans or peas.

Dietary fiber intake was associated with a significantly lower risk of RCC (Table 2). In a comparison of the highest with the lowest quintile, the association was similar for both soluble (HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.70, 0.97; P-trend = 0.02) and insoluble (HR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.65, 0.90; P-trend = 0.01; data in text only) fiber. However, when we evaluated fiber intake by food source, only fiber intake from legumes was significantly associated with a lower risk of RCC (HR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.69, 0.93; P-trend = 0.01).

TABLE 2.

HRs and 95% CIs for the association between dietary fiber intake and risk of renal cell carcinoma: NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study (n = 491,841)1

| Quintiles of intake |

||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | P-trend | |

| Fiber, total | ||||||

| Cases | 402 | 389 | 353 | 348 | 324 | |

| Median (g/1000 kcal) | 6.6 | 8.7 | 10.3 | 12.3 | 15.9 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.81 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.83, 1.10 | 0.75, 1.00 | 0.73, 0.99 | 0.69, 0.95 | 0.005 |

| Fiber, grain sources | ||||||

| Cases | 352 | 405 | 342 | 385 | 332 | |

| Median (g/1000 kcal) | 1.70 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 4 | 5.7 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 1.15 | 0.99 | 1.12 | 0.99 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 1.00, 1.33 | 0.85, 1.15 | 0.97, 1.30 | 0.84, 1.15 | 0.59 |

| Fiber, legume sources | ||||||

| Cases | 417 | 372 | 335 | 365 | 327 | |

| Median (g/1000 kcal) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 2.3 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.80 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.77, 1.02 | 0.69, 0.92 | 0.75, 1.00 | 0.69, 0.93 | 0.01 |

| Fiber, fruit sources | ||||||

| Cases | 379 | 379 | 357 | 363 | 338 | |

| Median (g/1000 kcal) | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.9 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.91 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.87, 1.16 | 0.82, 1.10 | 0.83, 1.13 | 0.77, 1.07 | 0.16 |

| Fiber, vegetable sources | ||||||

| Cases | 394 | 346 | 379 | 350 | 347 | |

| Median (g/1000 kcal) | 1.7 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 6.0 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.9 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.76, 1.02 | 0.84, 1.12 | 0.77, 1.04 | 0.78, 1.05 | 0.3 |

Cox proportional hazards regression model was adjusted for age, sex, education, race, marital status, family history of any cancer, BMI, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, and intake of alcohol, red meat, and total energy; fiber from various dietary sources was mutually adjusted for each other.

Intake of various fiber-rich plant foods was also associated with a lower risk of RCC (Table 3). In a comparison of the highest with the lowest quintile, we observed a significant inverse association with intake of whole grains (HR: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.73, 0.98; P-trend = 0.05) and a positive association with refined grain intake (HR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.39; P-trend = 0.04). Intake of legumes was also significantly associated with a lower risk of RCC (HR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.70, 0.95; P-trend = 0.01). We observed no association with total fruit and/or vegetable intake. Results were similarly null for intake of whole fruit (excluding juice) and nonstarchy vegetables. In a comparison of the highest with the lowest quintile, we observed a suggestive inverse association for total cruciferous vegetable intake (HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.72, 0.97; P-trend = 0.18). When we excluded cabbage/coleslaw from the total cruciferous vegetable group, we found that high intake of broccoli and cauliflower/Brussels sprouts was associated with a statistically significant lower risk of RCC per 100-g/1000 kcal (HR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.55, 0.98; P = 0.04; data in text only). Similarly, intake of whole citrus fruit (orange, tangerine, tangelo and grapefruit) was inversely associated with RCC per 100 g/1000 kcal (HR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.74, 0.98; P = 0.03; data in text only). No associations were observed for intake of carrots, corn, tomato, grapes, bananas, white potatoes, yams, or other individually queried items. We also observed no association across various botanical subgroups, such as Curcurbitaceae (eg, cucumber and melon) and Rosaceae (eg, apple, strawberry, pear, and peach/plum) or for color subgroups (eg, green-leafy, dark-green, orange, or yellow vegetables).

TABLE 3.

HRs and 95% CIs for the association between intake of fiber-rich plant foods and risk of renal cell carcinoma: NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study (n = 491,841)1

| Quintiles of intake |

||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | P-trend | |

| Whole grains | ||||||

| Cases | 408 | 373 | 330 | 358 | 347 | |

| Median (servings/1000 kcal)2 | 0.13 | 0.3 | 0.49 | 0.69 | 1.1 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.84 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.79, 1.06 | 0.70, 0.94 | 0.76, 1.02 | 0.73, 0.98 | 0.05 |

| Refined grains | ||||||

| Cases | 330 | 355 | 369 | 363 | 399 | |

| Median (servings/1000 kcal)2 | 1.39 | 1.88 | 2.26 | 2.67 | 3.35 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 1.09 | 1.19 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.92, 1.25 | 0.95, 1.30 | 0.93, 1.28 | 1.02, 1.39 | 0.04 |

| Legumes | ||||||

| Cases | 409 | 381 | 353 | 350 | 323 | |

| Median (servings/1000 kcal)3 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.82 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.81, 1.07 | 0.75, 1.00 | 0.74, 0.99 | 0.70, 0.95 | 0.01 |

| Total vegetables4 | ||||||

| Cases | 386 | 360 | 362 | 337 | 371 | |

| Median (servings/1000 kcal)5 | 0.52 | 0.79 | 1 | 1.28 | 1.83 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.97 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.81, 1.08 | 0.82, 1.09 | 0.76, 1.02 | 0.84, 1.12 | 0.62 |

| Nonstarchy vegetables4 | ||||||

| Cases | 394 | 356 | 364 | 343 | 359 | |

| Median (servings/1000 kcal)5 | 0.45 | 0.69 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 1.61 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.86 |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.80, 1.07 | 0.83, 1.12 | 0.79, 1.07 | 0.83, 1.14 | |

| Cruciferous vegetables | ||||||

| Cases | 418 | 368 | 317 | 386 | 327 | |

| Median (servings/1000 kcal)5 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.16 | 0.33 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 0.18 |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.78, 1.04 | 0.68, 0.92 | 0.85, 1.13 | 0.72, 0.97 | |

| Total fruit | ||||||

| Cases | 391 | 383 | 326 | 351 | 365 | |

| Median (servings/1000 kcal)5 | 0.3 | 0.67 | 1.01 | 1.44 | 2.26 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.98 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.86, 1.15 | 0.74, 1.00 | 0.80, 1.09 | 0.84, 1.15 | 0.69 |

| Whole fruit, excluding juice | ||||||

| Cases | 375 | 394 | 366 | 334 | 347 | |

| Median (servings/1000 kcal)5 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.59 | 0.9 | 1.52 | |

| Multivariable HR | 1.00 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.94 | |

| 95% CI | Reference | 0.91, 1.20 | 0.86, 1.16 | 0.76, 1.04 | 0.84, 1.17 | 0.14 |

Cox proportional hazards regression model was adjusted for age, sex, education, race, marital status, family history of any cancer, BMI, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, and intake of alcohol, red meat, and total energy; fruit, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains were mutually adjusted for each other.

MyPyramid Equivalents Database grains: 1 oz equivalent (28 g) = 1 slice bread; 0.5 cups rice, pasta, cooked cereal; 1 cup ready-to-eat cereal.

MyPyramid Equivalents Database legumes: 1 cup equivalent (8 oz, 225 g, or 237 mL) = 1 cup cooked dried beans or peas.

Does not include legumes.

MyPyramid Equivalents Database vegetables and fruit: 1 cup equivalent = 1 cup raw or cooked vegetable or fruit, 2 cups leafy salad greens, 1 cup vegetable or fruit juice, 0.5 cups dried fruit.

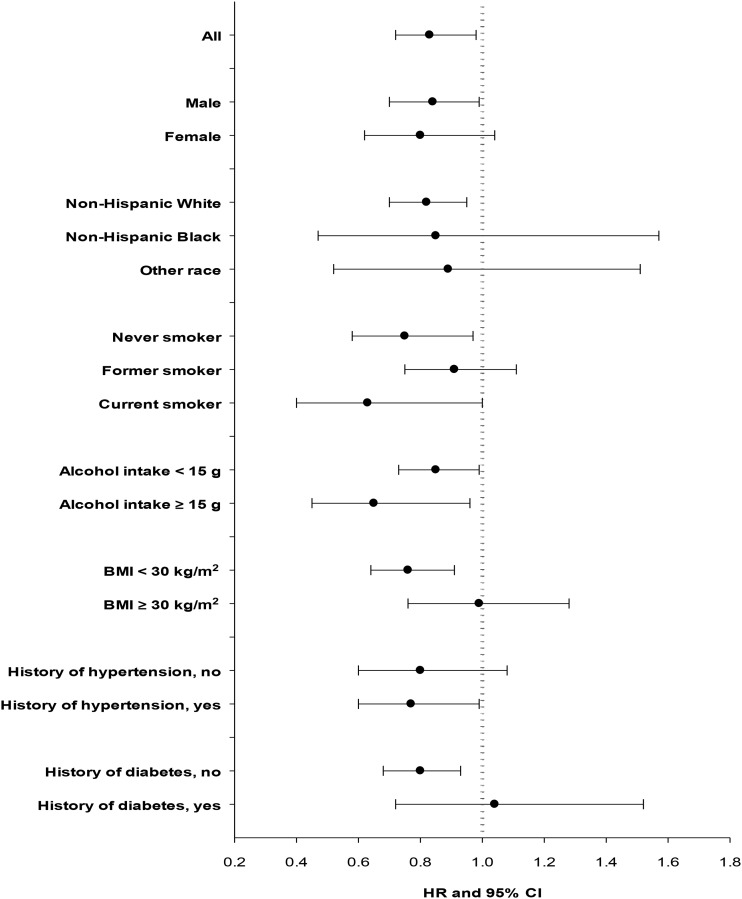

As shown in Figure 1, the association between total dietary fiber intake (per 10 g/1000 kcal) and RCC risk did not vary substantially by sex, race, alcohol intake, or history of hypertension (P-interaction > 0.20 for all). Fiber intake was associated with a lower risk of RCC regardless of smoking status (P-interaction = 0.09). We observed similar inverse associations in never-smokers (HR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.58, 0.97) and current smokers (HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.40, 1.00), but the reduction in risk was small and statistically insignificant among former smokers. Body mass was a strong effect modifier of the association between dietary fiber intake and RCC risk (P-interaction = 0.007). Fiber intake was associated with a significantly lower risk of RCC (HR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.64, 0.91) among nonobese participants (BMI <30) and was similarly associated with a lower risk in analyses restricted to normal-weight (BMI <25) participants only (HR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.51, 0.99; data in text only). However, no association was observed among the obese (BMI ≥30) participants (HR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.76, 1.28). Likewise, we observed no association among participants with a history of diabetes (HR: 1.04; 95%: 0.72, 1.52) but observed an inverse association among participants without a history of diabetes (HR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.68, 0.93; P-interaction = 0.10). Among participants who consumed at least one serving of red meat per day (≥50 g/1000 kcal), we observed a strong inverse association between fiber intake and RCC (HR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.30, 0.82), whereas a weaker inverse association was observed among participants who consumed less red meat (HR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.75, 1.01), but the interaction was only marginally significant (P = 0.05; data in text only). We observed no clear pattern of associations for fiber or fiber-rich foods by subtype among the subset of RCC cases with a more specific histopathologic classification.

FIGURE 1.

HRs and 95% CIs for renal cell carcinoma per 10-g/1000-kcal increase in dietary fiber intake according to selected characteristics. The dots indicate HRs, and the horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs. Dietary fiber intake was modeled as continuous (per 10 g/1000 kcal) in fully adjusted models. P-interaction values across the strata categories: 0.64, 0.67, 0.09, 0.20, 0.007, 0.96, and 0.10, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this large US cohort of middle-aged adults, dietary fiber intake was associated with a lower risk of RCC and was consistent among participants who never smoked, were not obese, and did not report a history of diabetes or hypertension. Over the past 2 decades, the association between fiber intake and RCC risk has been reported in one other prospective cohort (34) and in a handful of case-control studies (35–39). In the 2 largest studies, no association was observed in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (34), whereas total dietary fiber intake was inversely related to RCC risk in a large Canadian population-based case-control study (35). In clinical trials and prospective studies, dietary fiber intake has been linked to markers of renal health and cancer risk, including lower systemic inflammation and blood pressure levels, and to improved insulin sensitivity (4, 12, 40, 41).

Although our findings for dietary fiber intake were consistent across most RCC risk factors, including smoking status, alcohol intake, and history of hypertension, we observed no association between fiber and RCC among participants who were considered obese (BMI ≥30) or had a positive history of diabetes. The lack of an association in these 2 groups may reflect the modest effect of a single dietary component in cancer risk compared with the interplay of multiple carcinogenic and inflammatory mechanisms associated with obesity (42). However, it may also suggest that maintenance of normal body weight and/or normal blood glucose may be one pathway through which fiber intake may lower the risk of RCC. Fiber slows digestion and the postprandial glucose response by slowing the entry of glucose into the bloodstream, thereby reducing insulin stimulation (43). Because a fiber-rich meal is processed more slowly and nutrient absorption occurs over a greater period of time, fiber is linked to a number of positive effects on obesity- and insulin-related factors, including satiety, weight management, adiponectin levels, and diabetes risk (4, 44, 45). Beyond effects on weight and blood glucose control, fiber may also play a more direct role in RCC risk. Potentially proinflammatory colonic bacterial metabolism end products, such as phenols, indoles, and amines, are absorbed from the gut and cleared by the kidneys (46). Thus, a high-fiber diet, by altering gut metabolism, may decrease the generation and absorption of potential toxins (12). Furthermore, the fermentation of soluble dietary fiber by colonic bacteria produces short-chain fatty acids, which reenter the circulatory system and are linked to many positive effects from improved insulin sensitivity to antiinflammatory and anticancer properties (47). Among patients with chronic kidney disease, a condition of cumulative renal tissue damage and impaired function, high dietary fiber intake has been associated with lower serum concentrations of inflammatory markers and decreased mortality (12). Dietary fiber intake was also previously associated with decreased mortality due to cancer and inflammatory diseases in this (16) and other large prospective studies (13–15, 17).

Consistent with our findings for dietary fiber intake, some fiber-rich plant foods were also related to a lower risk of RCC, including legumes and whole grains. Two renal cancer case-control studies investigated various dietary sources of fiber and reported a significant inverse association for fiber from vegetables, but not grains or fruit (legumes were not evaluated separately) (36, 39). A single case-control study in Uruguay reported a significant inverse association between legume intake and renal cancer (48), whereas no association was observed in a large US cohort (9). We found very little previous data on whole grain intake and renal cancer, and only one Italian case-control study reported an inverse association for whole grains (49) and a positive association for refined grain food sources, such as bread and pasta (50). Compared with other dietary fiber sources, legumes contain the highest levels of resistant starch, which resists digestion through the stomach and small intestine until it reaches the bacteria within the colon and delivers many of the benefits of both soluble and insoluble fiber (42). In addition to fiber, whole grains and legumes are also rich in other vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals. For example, they each contain phytate or phytic acid (inositol hexophosphate)—a naturally occurring bioactive compound excreted in the urine and shown to inhibit the formation of renal calculi or kidney stones (51); however, there is only limited evidence to suggest that inositol hexophosphate may also play a role in cancer prevention (52).

Although we did not find total fruit or vegetable intake to be related to RCC risk, we observed suggestive inverse associations for cruciferous vegetables and whole citrus fruit. A pooled analysis of 13 cohorts reported that total fruit and vegetable intake (≥600 g/d compared with <200 g/d) was associated with an ∼30% reduced risk of RCC (6). Specific types of vegetables, including broccoli and carrots, were also inversely associated with RCC risk in the previous pooled analysis (6). However, results from individual cohorts in Europe, the United States, and Finland observed no association for total intake of fruit or vegetables (7, 9, 10). Similar to our findings, one US prospective investigation reported inverse associations between intake of cruciferous vegetables and vitamin C–rich fruit and vegetables and RCC risk, but only among men (9). The inverse association between cruciferous vegetables and RCC is further supported by findings in previous case-control studies (38, 39, 53, 54). Potential synergy among dietary fiber and other components of fiber-rich foods, such as antioxidants and bioactive compounds, challenge our ability to definitively determine whether dietary fiber per se or the other nutrients that are present in fiber-rich foods provide the potential health benefits. However, studies of antioxidant compounds and RCC risk have not yielded consistent results (7, 9, 39, 54).

To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective investigation of dietary fiber intake and RCC risk to date. Recognizing that a high intake of fiber and fiber-rich plant foods often clusters with a healthier overall eating pattern and lifestyle, we carefully considered the potential role of other risk factors related directly or indirectly to our exposure and outcome and conducted stratified analyses to begin to address this issue. The inverse association between dietary fiber intake and RCC risk remained among participants with healthy characteristics (eg, never-smokers, normal weight, or no history of hypertension), but the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured or unknown risk factors remains. The cohort provided a wide range of overall fiber intake for analyses, but associations with intake of fiber from various sources was not wholly consistent and was likely measured with some component of error. The finding for legumes and legume fiber is interesting; however, intake was relatively low in this population (median MyPyramid Equivalents Database servings in the highest quintile or top 20% equates to ∼2 cups of cooked dry beans or peas per week in a 2000-kcal-per-day diet). Further investigation of legumes and other fiber sources in a more ethnically diverse population with a wider range of intake could be informative. The prospective design avoids recall and selection bias, but it is also important to recognize that diet and lifestyle information ascertained by self-report from older adults at one point in time may not be entirely reflective of lifelong cumulative exposures or the most pertinent time period for RCC etiology. Because of the large number of comparisons, it is also possible that some of our findings may have been due to chance. Our new findings will need to be replicated in other prospective studies and biologically plausible mechanisms further explored.

In this large US cohort, intake of dietary fiber and several fiber-rich plant foods were associated with lower risk of RCC. The inverse association between dietary fiber intake and RCC was consistent among participants who never smoked, were normal-to-overweight, and did not report a history of diabetes or hypertension but did not hold among participants who were obese or had a history of diabetes. Our results did not definitively point to a particular source or type of fiber and may reflect potential synergy among dietary fiber and other components of fiber-rich foods. Overall, our findings support our hypothesis that plant-based and fiber-rich diets recommended for the prevention of cancer, as well as chronic conditions associated with RCC incidence, may play a role in RCC etiology both directly and indirectly. Our biologically plausible findings bring to light new hypotheses that can be explored further in epidemiologic and laboratory studies.

Acknowledgments

Cancer incidence data from the Atlanta metropolitan area were collected by the Georgia Center for Cancer Statistics, Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. Cancer incidence data from California were collected by the California Department of Health Services, Cancer Surveillance Section. Cancer incidence data from the Detroit metropolitan area were collected by the Michigan Cancer Surveillance Program, Community Health Administration, State of Michigan. The Florida cancer incidence data used in this report were collected by the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDC) under contract with the Florida Department of Health (FDOH). Cancer incidence data from Louisiana were collected by the Louisiana Tumor Registry, Louisiana State University Medical Center in New Orleans. Cancer incidence data from New Jersey were collected by the New Jersey State Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology Services, New Jersey State Department of Health and Senior Services. Cancer incidence data from North Carolina were collected by the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry. Cancer incidence data from Pennsylvania were supplied by the Division of Health Statistics and Research, Pennsylvania Department of Health, Harrisburg, PA. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions. Cancer incidence data from Arizona were collected by the Arizona Cancer Registry, Division of Public Health Services, Arizona Department of Health Services. Cancer incidence data from Texas were collected by the Texas Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch, Texas Department of State Health Services.

We are indebted to the participants in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study for their outstanding cooperation. We also thank Sigurd Hermansen and Kerry Grace Morrissey from Westat (study outcomes ascertainment and management) and Leslie Carroll and Adam Risch at Information Management Services (data support and analysis). We acknowledge the loss and memory of Arthur Schatzkin, visionary investigator who founded the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—CRD: conceived of the project, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript; and YP, W-HC, BIG, ARH, and RS: contributed to the design of the study, the analysis, and/or the study components. All authors critically reviewed and approved of the final manuscript. None of the authors had any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, et al. , SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2008. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow WH, Dong LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2010;7(5):245–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, Gansler T, Andrews KS, Thun MJ, Nutrition TACS, Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin 2006;56:254–81 (Published erratum appears in CA Cancer J Clin 2007;57(1):66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH, Jr, Ferreri S, Knudtson M, Koraym A, Waters V, Williams CL. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev 2009;67:188–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willett WC. Fruits, vegetables, and cancer prevention: turmoil in the produce section. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:510–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JE, Mannisto S, Spiegelman D, Hunter DJ, Bernstein L, van den Brandt PA, Buring JE, Cho E, English DR, Flood A, et al. Intakes of fruit, vegetables, and carotenoids and renal cell cancer risk: a pooled analysis of 13 prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18(6):1730–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Bertoia M, Albanes D, Mayne ST, Männistö S, Virtamo J, Wright ME. No association between fruit, vegetables, antioxidant nutrients and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2010;126:1504–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rashidkhani B, Lindblad P, Wolk A. Fruits, vegetables and risk of renal cell carcinoma: a prospective study of Swedish women. Int J Cancer 2005;113:451–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JE, Giovannucci E, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Curhan GC. Intakes of fruits, vegetables, vitamins A, C, and E, and carotenoids and risk of renal cell cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15(12):2445–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Weikert S, Boeing H, Pischon T, Olsen A, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Becker N, Linseisen J, Lahmann PH, Arvaniti A, et al. Fruits and vegetables and renal cell carcinoma: findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Int J Cancer 2006;118(12):3133–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Slavin JL. Position of the American Dietetic Association: health implications of dietary fiber. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:1716–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnamurthy VMR, Wei G, Baird BC, Murtaugh M, Chonchol MB, Raphael KL, Greene T, Beddhu S. High dietary fiber intake is associated with decreased inflammation and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2012;81:300–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajani UA, Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Dietary fiber and C-reactive protein: findings from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. J Nutr 2004;134:1181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs DR, Andersen LF, Blomhoff R. Whole-grain consumption is associated with a reduced risk of noncardiovascular, noncancer death attributed to inflammatory diseases in the Iowa Women's Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landberg R. Dietary fiber and mortality: convincing observations that call for mechanistic investigations. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:3–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park Y, Subar AF, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Dietary fiber intake and mortality in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1061–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chuang SC, Norat T, Murphy N, Olsen A, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Boutron-Ruault MC, Perquier F, Dartois L, Kaaks R, et al. Fiber intake and total and cause-specific mortality in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schatzkin A, Subar AF, Thompson FE, Harlan LC, Tangrea J, Hollenbeck AR, Hurwitz PE, Coyle L, Schussler N, Michaud DS, et al. Design and serendipity in establishing a large cohort with wide dietary intake distributions: the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:1119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Freedman LS, Carroll RJ, Subar AF, Brown CC, Butcher MS, Mouw T, Leitzmann M, et al. Performance of a food-frequency questionnaire in the US NIH-AARP (National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons) Diet and Health Study. Public Health Nutr 2008;11:183–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, McIntosh A, Rosenfeld S. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:1089–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subar AF, Midthune D, Kulldorff M, Brown CC, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A. Evaluation of alternative approaches to assign nutrient values to food groups in food frequency questionnaires. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tippett KS. Design and operation: the Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals and the Diet and Health Knowledge Survey, 1994-96. Beltsville, MD: US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 1998.

- 23.Prosky L, Asp NG, Furda I, DeVries JW, Schweizer TF, Harland BF. Determination of total dietary fiber in foods and food products: collaborative study. J Assoc Off Anal Chem 1985;68:677–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friday JE, Bowman SA. MyPyramid Equivalents Database for USDA Survey Food Codes, 1994-2002 version 1.0. Beltsville, MD: US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Community Nutrition Research Group; 2006. Available from: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg/ (cited 4 June 2012).

- 25.Smith SA, Campbell DR, Elmer PJ, Martini MC, Slavin JL, Potter JD. The University of Minnesota Cancer Prevention Research Unit vegetable and fruit classification scheme (United States). Cancer Causes Control 1995;6:292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Kahle LL, Midthune D, Potischman N, Schatzkin A. Evaluation of 2 brief instruments and a food-frequency questionnaire to estimate daily number of servings of fruit and vegetables. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71:1503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaud DS, Midthune D, Hermansen S, Leitzmann MF, Harlan LC, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A. Comparison of cancer registry case ascertainment with SEER estimates and self-reporting in a subset of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. J Registry Manag 2005;32:70–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO. International classification of diseases for oncology. 3rd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willett W, Stampfer MJ. Total energy intake: implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol 1986;124:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore SC, Chow W-H, Schatzkin A, Adams KF, Park Y, Ballard-Barbash R, Hollenbeck A, Leitzmann MF. Physical activity during adulthood and adolescence in relation to renal cell cancer. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George SM, Moore SC, Chow W-H, Schatzkin A, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE. A prospective analysis of prolonged sitting time and risk of renal cell carcinoma among 300,000 older adults. Ann Epidemiol 2011;21:787–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daniel CR, Cross AJ, Graubard BI, Park Y, Ward MH, Rothman N, Hollenbeck AR, Chow W-H, Sinha R. Large prospective investigation of meat intake, related mutagens, and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:155–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen NE, Roddam AW, Sieri S, Boeing H, Jakobsen MU, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Halkjaer J, Vineis P, Contiero P, et al. A prospective analysis of the association between macronutrient intake and renal cell carcinoma in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Cancer 2009;125(4):982–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Hu J, La Vecchia C, DesMeules M, Negri E, Mery L. Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research. Nutrient and fiber intake and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Nutr Cancer 2008;60:720–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galeone C, Pelucchi C, Talamini R, Negri E, Montella M, Ramazzotti V, Zucchetto A, Maso LD, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Fibre intake and renal cell carcinoma: a case-control study from Italy. Int J Cancer 2007;121:1869–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindblad P, Wolk A, Bergstrom R, Adami HO. Diet and risk of renal cell cancer: a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997;6:215–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolk A, Gridley G, Niwa S, Lindblad P, McCredie M, Mellemgaard A, Mandel JS, Wahrendorf J, McLaughlin JK, Adami HO. International renal cell cancer study. VII. Role of diet. Int J Cancer 1996;65(1):67–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Brock KE, Ke L, Gridley G, Chiu BC, Ershow AG, Lynch CF, Graubard BI, Cantor KP. Fruit, vegetables, fibre and micronutrients and risk of US renal cell carcinoma. Br J Nutr 2011:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King DE, Egan BM, Woolson RF, Mainous AG, 3rd, Al-Solaiman Y, Jesri A. Effect of a high-fiber diet vs a fiber-supplemented diet on C-reactive protein level. Arch Intern Med 2007;167(5):502–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.He K, Hu FB, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Willett WC, Liu S. Changes in intake of fruits and vegetables in relation to risk of obesity and weight gain among middle-aged women. Int J Obes 2004;28(12):1569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hursting SD, Dunlap SM. Obesity, metabolic dysregulation, and cancer: a growing concern and an inflammatory (and microenvironmental) issue. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1271:82–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slavin JL. Position of the American Dietetic Association: health implications of dietary fiber. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:1716–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.González Rodríguez DC, Solano RL, Gonzalez Martinez JC. [Adiponectin, insulin and glucose concentrations in overweight and obese subjects after a complex carbohydrates (fiber) diet.] Arch Latinoam Nutr 2009;59:296–303 (in Spanish). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi L, Rimm E, Liu S, Rifai N, Hu FB. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, cereal fiber, and plasma adiponectin concentration in diabetic men. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1022–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evenepoel P, Meijers BK, Bammens BR, Verbeke K. Uremic toxins originating from colonic microbial metabolism. Kidney Int Suppl 2009(114):S12–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Brownawell AM, Caers W, Gibson GR, Kendall CW, Lewis KD, Ringel Y, Slavin JL. Prebiotics and the health benefits of fiber: current regulatory status, future research, and goals. J Nutr 2012;142:962–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aune D, De Stefani E, Ronco A, Boffetta P, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Acosta G, Mendilaharsu M. Legume intake and the risk of cancer: a multisite case-control study in Uruguay. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20:1605–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.La Vecchia C, Chatenoud L, Negri E, Franceschi S. Session: whole cereal grains, fibre and human cancer wholegrain cereals and cancer in Italy. Proc Nutr Soc 2003;62:45–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bravi F, Bosetti C, Scotti L, Talamini R, Montella M, Ramazzotti V, Negri E, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Food groups and renal cell carcinoma: a case-control study from Italy. Int J Cancer 2007;120(3):681–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prieto RM, Fiol M, Perello J, Estruch R, Ros E, Sanchis P, Grases F. Effects of Mediterranean diets with low and high proportions of phytate-rich foods on the urinary phytate excretion. Eur J Nutr 2010;49:321–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vucenik I, Shamsuddin AM. Protection against cancer by dietary IP6 and inositol. Nutr Cancer 2006;55:109–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsu CC, Chow W-H, Boffetta P, Moore L, Zaridze D, Moukeria A, Janout V, Kollarova H, Bencko V, Navratilova M, et al. Dietary risk factors for kidney cancer in eastern and central Europe. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan JM, Gago-Dominguez M, Castelao JE, Hankin JH, Ross RK, Yu MC. Cruciferous vegetables in relation to renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 1998;77:211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]