Abstract

Stem-like cells and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) program are postulated to play important roles in various stages of cancer development, but their roles in breast cell carcinogenesis and intervention remain to be clarified. We investigated stem-like cell- and EMT-associated properties and markers in breast epithelial cells chronically exposed to low-dose 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and benzo[a]pyrene in the presence and absence of the preventive agents green tea catechins and grape seed extract. Our results indicate that stem-like cell- and EMT-associated properties and markers should be seriously considered as new cancer-associated indicators for detecting breast cell carcinogenesis and as endpoints for intervention of carcinogenesis.

Keywords: breast cell carcinogenesis, cancer stem-like cells, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, intervention of carcinogenesis, low-dose carcinogens

1. Introduction

Carcinogenesis of human breast epithelial cells from non-cancerous to pre-malignant and malignant stages is a multiyear, multistep, and multipath disease process involving cumulative genetic and epigenetic alterations [1,2]. More than 85% of breast cancers are sporadic and attributable to long-term exposure to environmental factors, such as chemical carcinogens [1–5]. Over 200 chemical carcinogens have been experimentally detected to acutely induce malignancy in cultured breast cells or mammary tumors in animals [1,3,5]. These carcinogens have been studied at high doses of micro- to milli-molar concentrations [1,3,6], which is appropriate in examining occupational exposure. However, considering that carcinogenesis of human tissues involves long-term exposure to environmental carcinogens at low doses, a high-dose approach may not serve as a proper way to study environmental exposure. Thus, it is imperative to take a chronic, low-dose approach to reveal environmental mammary carcinogens, at physiologically-achievable levels, capable of inducing human breast cell carcinogenesis.

Our carcinogenesis model has revealed that cumulative exposures to two environmental carcinogens, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), at physiologically-achievable pico-molar concentrations [7–10], induce immortalized, non-cancerous, human breast epithelial MCF10A cells to increasingly acquire cancer-associated properties [11–16]. NNK is a potent tobacco carcinogen in causing lung cancer [17]; although gastric administration of NNK into rats results in DNA-adduct formation in the mammary gland and development of mammary tumors [17–20], NNK is not currently recognized as a breast carcinogen. B[a]P, on the other hand, is an environmental, dietary, and tobacco carcinogen that is recognized as a mammary carcinogen in rodents; its metabolites form strong DNA adducts and cause DNA lesions [1,4,10,21–24]. Increasing epidemiological studies suggest a contributing role of tobacco carcinogens in breast cancer development [25–29]. Therefore, it is important to understand the activity of NNK and B[a]P, at physiologically-achievable levels, in inducing breast cell carcinogenesis.

In our model [11–16], 24 hours after subculturing, MCF10A cultures received 48-hour exposure to individual or combined NNK and B[a]P, each at 100 pM, as one exposure cycle, and cultures undergo 5 to 20 cycles of carcinogen exposure to induce progressive carcinogenesis. We detected that NNK and B[a]P exhibit comparable abilities to progressively induce breast epithelial cell carcinogenesis [15]. Although the combination of NNK and B[a]P additively increases degrees of acquired cancer-associated properties, the cumulative exposures to combined NNK and B[a]P were insufficient to induce cells to acquire tumorigenicity necessary to develop xenograft tumors in immune-deficient mice; thus, these non-tumorigenic NNK- and B[a]P-exposed cells are regarded as pre-malignant cells [15]. Hence, our model allows us to detect low-dose carcinogens capable of inducing non-tumorigenic, pre-malignancy of breast cells.

Using our model, we have already detected that green tea catechins (GTC) and grape seed proanthocyanidin extract (GSPE), at non-cytotoxic concentrations, are effective in intervention of NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis, measured by their ability to suppress the cancer-associated properties of reduced dependence on growth factors, anchorage-independent growth, and acinar-conformational disruption [12–16]. In rats, GTC has been shown to suppress mammary carcinogenesis induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and N-methyl-N-nitrosourea [30,31], and GSPE shows diet-dependent, chemopreventive activity in suppression of mammary tumors induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene [32]. Thus, it is important to further understand the preventive activity of GTC and GSPE in intervention of pre-malignant, breast cell carcinogenesis chronically induced by low-dose environmental carcinogens. Understanding such activity will be highly valuable to the intervention of pre-malignant carcinogenesis to reduce the health risk of sporadic breast cancer associated with long-term exposure to low doses of carcinogens.

It has been postulated that cancer stem-like cells are involved in generating and maintaining pre-malignant and malignant lesions [33–35], and development of stem-like cells may involve induction of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) program [36]. However, it is not clear whether cancer stem-like cells and the EMT program can be induced by long-term exposure to low doses of carcinogens in breast cell carcinogenesis. Whether preventive agents, like GTC and GSPE, are able to suppress the induction of cancer stem-like cells and the EMT program also remains to be clarified.

In this communication, we report the investigation of stem-like cell- and EMT-associated properties and markers progressively induced by chronic exposure of breast epithelial cells to low-dose NNK and B[a]P. We also used these properties and markers as targeted endpoints to verify the activity of non-cytotoxic GTC and GSPE in suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis. Our results suggest that the measurable, stem-like cell- and EMT-associated properties and markers should be considered as new cancer-associated indicators for detecting carcinogenesis of breast cells and targeted endpoints for preventive agents in intervention of carcinogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell cultures and reagents

Immortalized, non-cancerous, human breast epithelial MCF10A (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Rockville, MD) and derived cell lines were maintained in complete MCF10A (CM) medium (1:1 mixture of DMEM/Ham’s F12, supplemented with 100 ng/ml cholera enterotoxin, 10 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisol, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, and 5% horse serum) [15]. Human breast adenocarcinoma MCF7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. All cultures were maintained in medium supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in 5% CO2 at 37° C and subcultured every 3 days [15]. Stock aqueous solutions of NNK (Chemsyn, Lenexa, KS) and B[a]P (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) were prepared in DMSO and diluted with culture medium for assays. GTC (Polyphenon-60, a mixture of polyphenolic compounds containing 60% total catechins; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and GSPE (contains 74% proanthocyanidins; InterHealth Nutraceuticals, Benicia, CA) were prepared in distilled water and diluted with medium.

2.2. Cell lines for studies of induction and suppression of cell carcinogenesis

Twenty-four hours after each subculturing, MCF10A cells were treated with combined NNK and B[a]P each at 100 pM in the absence and presence of GTC or GSPE, at the maximal non-cytotoxic, preventive concentration of 40 μg/ml [13,16], for 48 hours, followed by subculturing, as one cycle of exposure [11–16]. MCF10A cells were repeatedly exposed to combined NNK and B[a]P for 5, 10, and 20 cycles to result in NB5, NB10, and NB20 cell lines, respectively. Cells were repeatedly exposed to combined NNK and B[a]P in the presence of GTC or GSPE for 20 cycles to result in NB/T-20 and NB/G-20 cell lines, respectively. After designated cycles of exposure, these cell lines were maintained, as stable cell lines, in CM medium in the absence of NNK, B[a]P, GTC, or GSPE and subcultured every 3 days.

2.3. Reduced dependence on growth factors assay

The low-mitogen (LM) medium contained reduced total serum and mitogenic additives to 2% of the concentration formulated in CM medium as described above [12–16]. One × 104 cells were seeded in 60-mm culture dishes and maintained in LM medium. Growing cell colonies that reached 0.5 mm diameter in 10 days were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and identified as cell clones acquiring the cancer-associated property of reduced dependence on growth factors.

2.4. Anchorage-independent cell growth assay

The base layer consisted of 2% low-melting agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) in CM medium. Then, 0.4% low-melting agarose in a mixture (1:1) of CM medium with 3-day conditioned medium prepared from MCF10A cultures was mixed with 5 × 104 cells and plated on top of the base layer in 60-mm diameter culture dishes. Growing colonies that reached 0.1 mm diameter by 20 days were identified as cell clones acquiring the cancer-associated property of anchorage-independent growth [12–16].

2.5. Cell mobility-healing assay

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and grown to confluence in CM medium. Cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and maintained in DMEM/Ham’s F12 medium supplemented with 2% horse serum for 15 hours [37]. The monolayer was then scratched with a 23-gauge needle (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to generate wounds and rinsed with CM medium to remove floating cells. Cultures were maintained in CM medium, and the wounded areas were examined 6 hours and 20 hours after scratches to detect healing. The area not healed by the cells was subtracted from the total area of the initial wound to calculate the wound healing area at time intervals of 6 hours and 24 hours, using Total Lab TL100 software (Total Lab, Newcastle, NE) [15,16].

2.6. In vitro cell invasion and migration assay

The in vitro cell invasion assay was performed using 24-well Transwell insert-chambers with a polycarbonate filter with a pore size of 8.0 μm (Corning Costar, Lowell, MA). The upper side of the filter was coated with a Matrigel membrane (BD Biosciences). Two × 104 cells in serum-free medium were seeded on top of the Matrigel-coated filter in each insert-chamber. Then, insert-chambers were placed into wells on top of culture medium containing 10% horse serum as a chemoattractant. After 24 hours, the invasive ability of cells was determined by the number of cells translocated to the lower side of filters [15,38]

The in vitro migration assay was performed using 24-well Transwell insert-chambers with a polycarbonate filter without Matrigel. The migration ability of cells was determined by the number of cells translocated to the lower side from the upper side of filters [38,39].

2.7. Mammosphere formation

Cells were seeded on 100-mm culture dishes on top of a 1% agarose-coated, non-adherent culture plate, incubated in serum-free, complete MCF10A medium supplemented with 0.4% bovine serum albumin, and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37° C for 7 to 10 days to develop the primary mammospheres. Mammospheres were collected by centrifugation and dissociated enzymatically with 0.25% trypsin and pipetting; cell suspension was then seeded on non-adherent culture plates to develop the secondary mammospheres, and then cell suspension was prepared from the secondary mammospheres and seeded on non-adherent culture plates to develop the tertiary mammospheres [40].

2.8. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) assay

An ALDEFLUOR Kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) was used to detect ALDH-expressing cells [38]. One × 105 cells/ml were resuspended in assay buffer, mixed with activated Aldefluor substrate BAAA (BODIPY-aminoacetaldehyde), and incubated in the presence and absence of the ALDH inhibitor diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB) at 37° C for 40 minutes. Then, cells were resuspended in assay buffer for flow cytometric analysis by using a 15 milliwatt air-cooled argon laser to produce 488 nm light [41]. Fluorescence emission was collected with a 529-nm band pass filter. The mean fluorescence intensity of cells was quantified using Multicycle software (Phoenix Flow System, San Diego, CA). Cells incubated with BAAA in the presence of DEAB were used to establish the baseline of fluorescence for determining the ALDH-expressing cell population (%) in which ALDH activity was not inhibited by DEAB.

2.9. Immunofluorescence detection of CD44+ and CD24+ cells

Mammospheres were collected, rinsed with glycine wash buffer (130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4, 3.5 mM, NaH2PO4, and 100 mM glycine), fixed with 0.1% formaldehyde, and suspended in blocking buffer (130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4, 3.5 mM NaH2PO4, 8 mM NaN3, 0.1% BSA, 0.2% TritonX-100, and 0.05% Tween 20) [42]. Mammospheres were then incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated CD44-specific antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated CD24-specific antibody (BD Biosciences) at 4° C for 15 hours, followed by rinses with PBS and 0.1% Tween 20. CD44+ and CD24+ cells in mammospheres were imaged by confocal epifluorescence microscopy (Leica TCS SP2, Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany) and analyzed with Leica Lite software (Leica Microsystems). Then, the relative intensity of CD44 to CD24 in mammospheres was analyzed by ImageJ software [43].

2.10. Flow cytometric detection of CD44+ and CD24+ cells

Cells were trypsinized and rinsed with glycine wash buffer, fixed with 0.1% formaldehyde, resuspended in blocking buffer [42], and incubated with PE-conjugated CD44-specific antibody and FITC-conjugated CD24-specific antibody (BD Biosciences) at 4° C for 15 hours, as described above. Cells were then rinsed and resuspended in PBS. One × 105 cells/ml were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine CD44+ and CD24+ cell populations.

2.11. Western immunoblotting

Cells were lysed, and equal amounts of proteins in cell lysates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose filters for immunoblotting, as previously described [15,16]. Antibodies specific to E-Cadherin, Ep-CAM, MMP-9, Vimentin, and β-Actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antigen-antibody complexes on filters were detected by the Supersignal chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

2.12. Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to establish significant difference between various treatment groups; a P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Then, a pairwise analysis of dependent variables was performed with the Duncan multiple range test to verify the significance of differences between groups [15].

Statistical significance was analyzed by the Student t test; α levels were adjusted by the Simes method [44]. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis

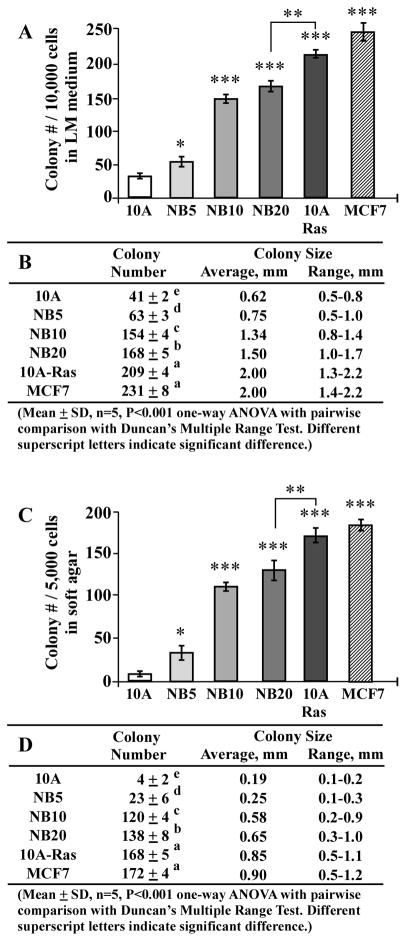

Acquisition of tumorigenicity is regarded as the key criterion for experimentally determining cellular malignancy; however, many human malignant cells, such as urinary bladder cancer J82 cells, are not tumorigenic [45]. Thus, other measurable, cancer-associated properties are needed in studying induction and intervention of cellular carcinogenesis. One such property, reduced dependence on growth factors, contributes to aberrantly-increased cell survivability and ultimately to cellular carcinogenesis [46–48]. Anchorage-independent growth also promotes aberrantly-increased cell survivability and contributes to cellular carcinogenesis because cell adhesion or anchorage to extracellular matrixes is important for normal cell survival in a multi-cell environment [49–50]. We have routinely used these two cancer-associated properties of reduced dependence on growth factors and anchorage-independent growth as targeted endpoints for measuring the progression of cellular carcinogenesis [12–15]. As demonstrated in previous reports [14,15], cumulative exposures of MCF10A cells to combined NNK and B[a]P, each at physiologically-achievable concentrations of 100 pM, for 5, 10, and 20 cycles, resulting in stable NB5, NB10, and NB20 cell lines, respectively. Increased exposures to NNK and B[a]P induced cells to acquire increased degrees of these two cancer-associated properties in an exposure-dependent manner, as determined by increased numbers of cell clones survived in LM medium and soft agar, respectively (Fig. 1). Additional studies revealed that cumulative exposures to NNK and B[a]P resulted in not only increased numbers but also increased sizes of cell colonies in LM medium (Fig. 1A and B) and soft agar (C and D) (MCF10A < NB5 < NB10 <NB20). As a comparison, two malignant cell lines, oncogenic H-Ras-expressing, MCF10A-Ras and the estrogen receptor-positive human breast adenocarcinoma MCF7 [51,52], developed higher numbers and larger sizes of cell colonies than did the pre-malignant NB5, NB10, and NB20 cells. These results indicate that cumulative exposures of breast cells to NNK and B[a]P resulted in increasing acquisition of the cancer-associated properties of reduced dependence on growth factors and anchorage-independent growth; however, these pre-malignant NNK- and B[a]P-exposed cell lines acquired significantly lower degrees of these cancer-associated properties than the malignant MCF10A-Ras and MCF7 cells.

Fig. 1.

NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis. MCF10A (10A) cells were repeatedly exposed to NNK combined with B[a]P each at 100 pM for 5, 10, and 20 cycles, resulting in NB5, NB10, and NB20 cell lines, respectively. MCF10A cells were stably transfected to ectopically express oncogenic H-Ras, resulting in MCF10A-Ras (10A-Ras) cells. MCF10A-Ras and MCF7 cell lines were used as malignant control lines. (A) To determine acquisition of the cancer-associated property of reduced dependence on growth factors, cells were seeded in LM medium for 10 days; cell colonies (≥ 0.5 mm diameter) were counted. (C) To determine acquisition of the cancer-associated property of anchorage-independent growth, cells were seeded in soft agar for 20 days; cell colonies (≥ 0.1 mm diameter) were counted. Columns, mean of triplicates; bars, SD. All results are representative of three independent experiments. The Student t test was used to analyze statistical significance, indicated by * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001; α levels were adjusted by the Simes method. (B and D) Tables show colony numbers, average colony size, and range of colony size determined in (A) and (C), respectively. Mean colony numbers in each group were analyzed by one-way ANOVA at P < 0.001 to indicate significant difference in number of colonies in various groups. To further determine the significant difference between individual groups, a pairwise analysis of variables was performed using the Duncan multiple range test. Means with different superscript letters (a, b, c, d, and e) indicate significant difference at P < 0.001 between groups; no significant difference was seen between groups with the same superscript.

3.2 NNK- and B[a]P-induced stem-like cell properties

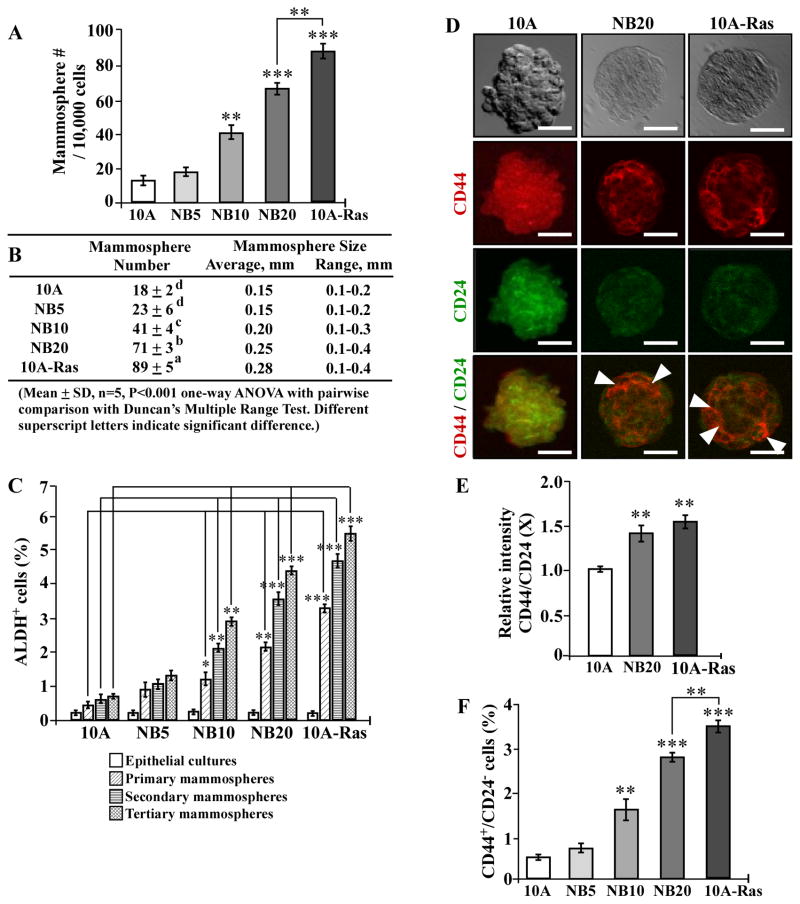

Stem-like cells are able to self-renew in serum-free medium and develop mammospheres in non-adherent cultures [40]. Considering the stem-like cell property of serum-independent, non-adherent growth, stem-like cells appear to acquire abilities of both reduced dependence on growth factors and anchorage-independent growth. Thus, whether cellular carcinogenesis may increase stem-like cells is an important question to be clarified. Breast stem-like cells exhibit high levels of ALDH activity [41] and express a high level of cell surface marker CD44 with a low level of CD24 [53]. Subpopulations of stem-like ALDH+ and CD44+/CD24− cells have been reportedly detected in MCF7 cultures [54,55]. Thus, whether ALDH+ and CD44+/CD24− cell populations are induced in NNK- and B[a]P-exposed MCF10A cells needs to be determined. Using agarose-coated culture plates, we successfully grew mammospheres from non-cancerous MCF10A, NNK- and B[a]P-exposed MCF10A, and MCF10A-Ras cells. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, accumulated exposures of MCF10A cells to NNK and B[a]P resulted in increased numbers and sizes of mammospheres in an exposure-dependent manner, as detected in parental and pre-malignant NB5, NB10, and NB20 cultures; higher numbers and larger sizes of mammospheres developed in MCF10A-Ras cultures than in NB5, NB10, and NB20 cultures. To verify if mammospheres acquired the stem-like cell property of self-renewal, mammospheres were maintained in non-adherent cultures and subcultured for two additional passages, resulting in primary, secondary, and tertiary mammospheres; non-stem-like cells that lack the ability of self-renewal would show limited growth and undergo anoikis in three passages [56]. Upon analysis, we detected significantly increased ALDH+ cell populations in mammospheres developed in NB10, NB20, and MCF10A-Ras cultures versus MCF10A counterpart cultures (Fig. 2C). Higher populations of ALDH+ cells developed in MCF10A-Ras cultures than in NB10 and NB20 cultures. Tertiary mammospheres contained higher populations of ALDH+ cells than secondary and primary counterpart mammospheres, and secondary mammospheres contained higher populations of ALDH+ cells than primary counterpart mammospheres. The results indicated that stem-like cell populations were enriched by increased passages. Using PE-conjugated CD44-specific antibody and FITC-conjugated CD24-specific antibody with confocal epifluorescence microscopy, we detected CD44+ and CD24+ cells in mammospheres (Fig. 2D). Analysis of CD44+ and CD24+ cell images revealed a higher relative intensity of CD44 to CD24 in NB20 and MCF10A-Ras mammospheres than in the parental MCF10A mammospheres (Fig. 2E). When we further analyzed CD44+ and CD24+ cell populations in mammospheres with flow cytometry, we detected significantly increased CD44+/CD24− cell populations in mammospheres of NB10, NB20, and MCF10A-Ras cells versus parental MCF10A counterpart cells; also, higher populations of CD44+/CD24− cells developed in MCF10A-Ras mammospheres than in NB10 and NB20 mammospheres (Fig. 2F). Thus, cumulative exposures to NNK and B[a]P resulted in increased stem-like cell population, which may be considered as a new cancer-associated property to be used to measure progress of cellular carcinogenesis.

Fig. 2.

NNK- and B[a]P-induced stem-like cell properties. (A) To determine cellular acquisition of the ability of serum-independent non-adherent growth, 1 × 104 MCF10A (10A), NB5, NB10, NB20, and MCF10A-Ras (10A-Ras) cells were seeded in non-adherent cultures for 10 days; then, mammospheres (≥ 0.1 mm diameter) were counted. (B) The table shows mammosphere numbers, average size, and range of size determined in (A). Mean mammosphere numbers in each group were analyzed by one-way ANOVA at P < 0.001 to indicate significant difference in number of colonies in various groups. To further determine the significant difference between individual groups, a pairwise analysis of variables was performed using the Duncan multiple range test. Means with different superscript letters (a, b, c, and d) indicate significant difference at P < 0.001 between groups. (C) Parental epithelial cells, and primary, secondary, and tertiary mammospheres were trypsinized, and ALDH-expressing (ALDH+) cell population (%) was determined by flow cytometry. (D) Representative images of co-immuno-staining of MCF10A, NB20, and MCF10A-Ras primary mammospheres with PE-conjugated CD44-specific antibody and FITC-conjugated CD24-specific antibody. Bars, 100 μm; magnification, 400X. Arrowheads indicate CD44+/CD24− cells. (E) The relative intensity of CD44 to CD24 (CD44/CD24) in mammospheres detected in 2D was analyzed by ImageJ, the level set in control MCF10A mammospheres as 1 (X, arbitrary unit). (F) Primary mammospheres were collected and trypsinized, cells were incubated with PE-conjugated CD44-specific antibody and FITC-conjugated CD24-specific antibody, and CD44+/CD24− cell population (%) was determined by flow cytometry. Columns, mean of triplicates; bars, SD. All results are representative of at least three independent experiments. The Student t test was used to analyze statistical significance, indicated by * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001; α levels were adjusted by the Simes method.

3.3. NNK- and B[a]P-induced EMT-associated properties and markers

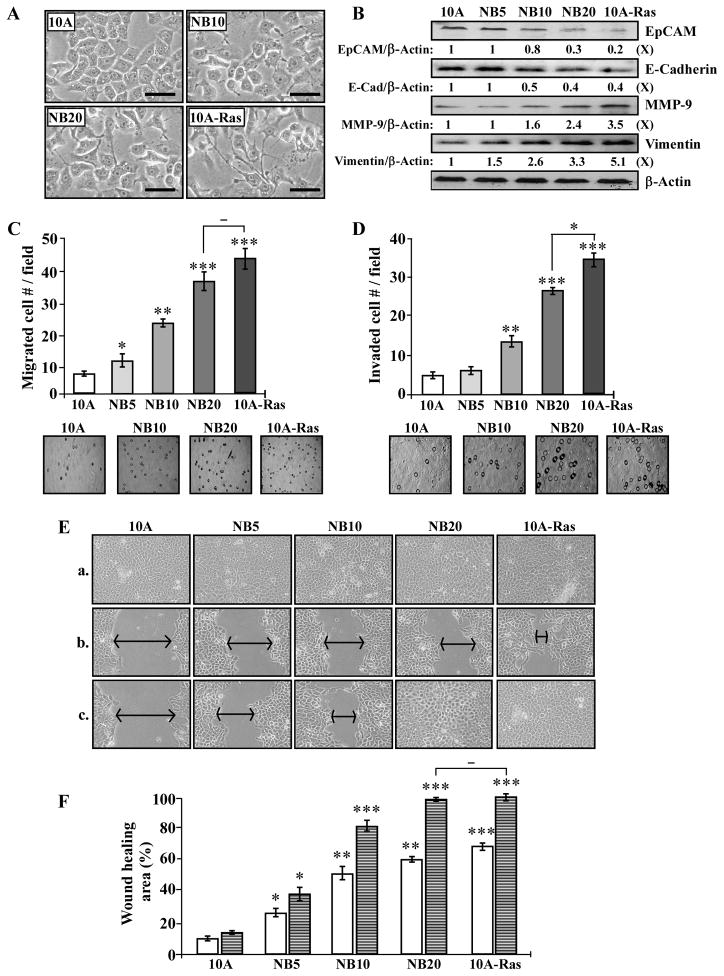

Studies have shown that the EMT program is involved in development of stem-like cells [36]. When the EMT program is induced in epithelial cells, the cells exhibit the fibroblastoid morphology of mesenchymal cells with increased invasive ability [57,58]. Ectopic expression of oncogenic H-Ras in MCF10A cells also induces mesenchymal morphology and EMT-associated markers [59]. In investigating whether chronic NNK and B[a]P exposure resulted in induction of the EMT program, we observed morphologic changes of MCF10A cells from a compactly-attached cobblestone-like epithelial morphology to a stable dispersed, spindle-like mesenchymal morphology in NB10 and NB20 cultures, compared with MCF10A-Ras cells, which exhibit typical mesenchymal cell morphology (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

NNK- and B[a]P-induced EMT-associated properties. (A) Representative morphological features of MCF10A (10A), NB10, NB20, and MCF10A-Ras (10A-Ras) cells. Bars, 100 μm; magnification, 400X. (B) Cell lysates were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using specific antibodies to detect levels of EpCAM, E-Cadherin, MMP-9, and Vimentin, with β-Actin as a control, and these levels were quantified by densitometry. The levels of EpCAM, E-Cadherin, MMP-9, and Vimentin were calculated by normalizing with the level of β-Actin and the level set in MCF10A cells (lane 1) as 1 (X, arbitrary unit). (C) Cellular migratory and (D) invasive activities were determined by counting the numbers of cells translocated through a polycarbonate filter without or with coated Matrigel, respectively, in 10 arbitrary visual fields. Panels show representative fields of migrated and invasive cells determined in (C) and (D). (E) Cellular acquisition of increased mobility was determined by wound healing assay. Cells were seeded in CM medium and grown to confluence (a); then, a linear area of cell layer was removed from each culture with a 23-gauge needle to produce wounded cultures, and the wounded areas were examined (magnification, 100X) 6 (b) and 20 hours (c) afterward. Arrows indicate width of wounded areas. (F) To quantitatively measure cell mobility detected in (E), the area not healed by the cells was subtracted from the total area of the initial wound to calculate the wound healing area (%) at intervals of 6 (white columns) and 20 hours (striated columns). Columns, mean of triplicates; bars, SD. All results are representative of three independent experiments. The Student t test was used to analyze statistical significance, indicated by * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001; α levels were adjusted by the Simes method.

Studying EMT-associated markers, we detected decreased levels of the epithelial markers E-Cadherin and EpCAM as well as increased levels of the mesenchymal markers Vimentin and MMP-9 in NB10, NB20, and MCF10A-Ras cells (Fig. 3B); changes of these EMT-associated markers were in concert with increased degrees of cellular carcinogenesis. During the EMT, reduction of E-Cadherin and EpCAM is involved in loss of cell-cell adhesion [60,61], while an increase of MMP-9 is involved in the breakdown of the extracellular matrix [62], and increased Vimentin is involved in filament expression and increased mobility [63]. Thus, addressing whether cellular carcinogenesis resulted in acquisition of EMT-associated properties [58], we detected increased levels of the EMT-associated properties of cell migration (Fig. 3C) and invasion (D) acquired by NB10 and NB20 cells; NB20 acquired higher levels of these properties than NB10 and levels comparable to MCF10A-Ras cells in cell migration, but significantly less than MCF10A-Ras cells in cell invasion. In addition, using a scratch/wound assay [37], we detected that NB20 cells acquired higher degrees of cell mobility than NB10 and NB5 cells, and NB20 cells acquired a degree of cell mobility comparable to MCF10A-Ras cells (Fig. 3E and F). Accordingly, these results indicate that cumulative exposures to NNK and B[a]P resulted in acquisition of EMT-associated properties in an exposure-dependent manner.

The ability of carcinogenic epithelial cells to produce increased stem-like cell populations in mammospheres may be mediated by the EMT program, as indicated by other studies [40,59,64]. Cancer stem-like cells have been postulated to play important roles in pre-malignant and malignant stages of cancer development [33,34,35], as well as in recurrent cancers after chemotherapy [65]. Thus, stem-like cell properties and EMT-associated properties and markers need to be seriously considered as new cancer-associated properties to be used as endpoints in measuring carcinogenesis progression.

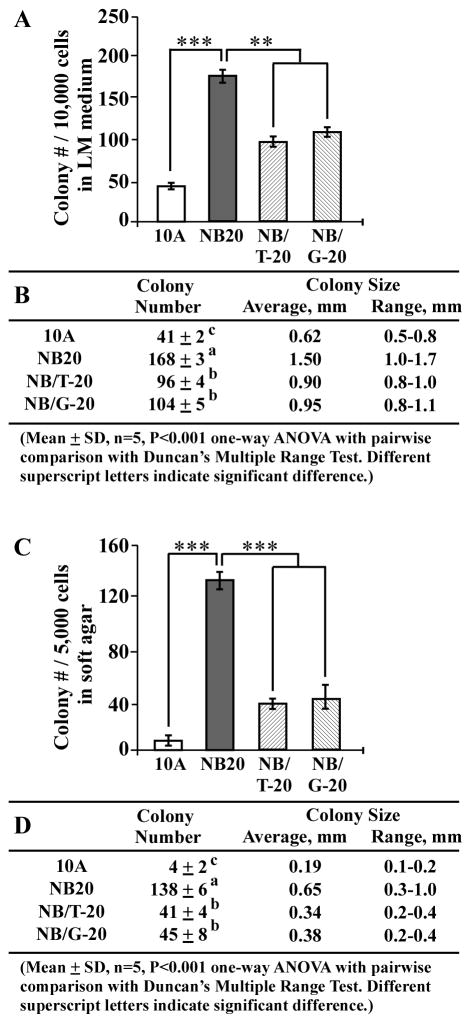

3.4. GTC and GSPE suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis

Using the cancer-associated properties of reduced dependence on growth factors and anchorage-independent growth as targeted endpoints, we investigated the activity of GTC and GSPE in suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis. Cumulative exposures of MCF10A cells to NNK and B[a]P in the presence of GTC and GSPE for 20 cycles resulted in NB/T-20 and NB/G-20 cell lines, respectively. Consistent with our reported results [14,15], GTC and GSPE at their maximal, non-cytotoxic concentration of 40 μg/ml were effective in suppressing the number of cell clones acquiring reduced dependence on growth factors (Fig. 4A and B) and anchorage-independent growth (C and D) in cultures of NB/T-20 and NB/G-20 cells versus NB20 cells. We detected that co-exposure to GTC or GSPE resulted in decreasing not only the numbers but also sizes of cell clones in LM medium (Fig. 4B) and soft agar (4D), indicating that co-exposure to GTC or GSPE reduced the NNK- and B[a]P-induced abilities of reduced dependence on growth factors and anchorage-independent growth. Exposure of MCF10A cells to GTC or GPSE alone did not result in any detectable changes in colony number or size (data not shown). These results indicate that non-cytotoxic GTC and GSPE were able to qualitatively and quantitatively suppress NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis.

Fig. 4.

GTC and GSPE suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis. MCF10A (10A) cells were repeatedly exposed to NNK combined with B[a]P each at 100 pM in the presence of GTC and GSPE at 40 μg/ml for 20 cycles, resulting in NB/T-20 and NB/G-20 cell lines, respectively. (A) To determine acquisition of the cancer-associated property of reduced dependence on growth factors, MCF10A, NB20, NB/T-20, and NB/G-20 cells were seeded in LM medium for 10 days; cell colonies (≥ 0.5 mm diameter) were counted. (C) To determine cellular acquisition of the cancer-associated property of anchorage-independent growth, cells were seeded in soft agar for 20 days; cell colonies (≥ 0.1 mm diameter) were counted. Columns, mean of triplicates; bars, SD. All results are representative of three independent experiments. The Student t test was used to analyze statistical significance, indicated by ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001; α levels were adjusted by the Simes method. (B and D) Tables show colony numbers, average colony size, and range of colony size determined in (A) and (C), respectively. Mean colony numbers in each group were analyzed by one-way ANOVA at P < 0.001 to indicate significant difference in number of colonies in various groups. To further determine the significant difference between individual groups, a pairwise analysis of variables was performed using the Duncan multiple range test. Means with different superscript letters (a, b, and c) indicate significant difference at P < 0.001 between groups.

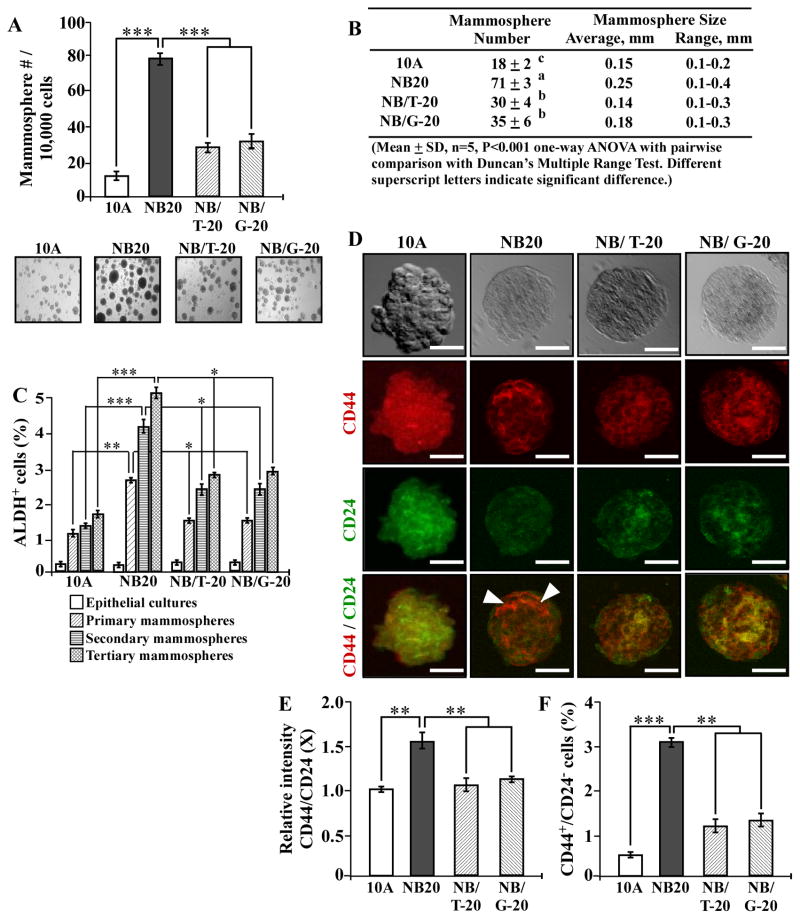

3.5. GTC and GSPE suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced stem-like cell properties

Using the stem-like cell properties of mammosphere formation and increased ALDH-positive and CD44+/CD24− cell populations as targeted endpoints, we furthered our investigation of GTC’s and GSPE’s activity in suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis. As shown in Fig. 5, co-exposure to GTC or GSPE reduced the numbers and sizes of mammospheres (A and B) as well as ALDH+ (C) and CD44+/CD24− (D, E, and F) cell populations in mammospheres induced by NNK and B[a]P, as determined in NB/T-20 and NB/G-20 cultures versus NB20 cultures. Exposure of MCF10A cells to GTC or GPSE alone did not result in any detectable changes in mammosphere number and size or ALDH+ and CD44+/CD24− cell populations (data not shown). These results indicate that non-cytotoxic GTC and GSPE were able to suppress NNK- and B[a]P-induced stem cell-like properties.

Fig. 5.

GTC and GSPE suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced stem-like cell properties. (A) To determine cellular acquisition of the ability of serum-independent non-adherent growth, 1 × 104 MCF10A (10A), NB20, NB/T-20, and NB/G-20 cells were seeded in non-adherent cultures for 10 days; then, mammospheres (≥ 0.1 mm diameter) were counted. Panels show representative fields of mammosphere cultures. (B) Table shows mammosphere numbers, average size, and range of size determined in (A). Mean mammosphere numbers in each group were analyzed by one-way ANOVA at P < 0.001 to indicate significant difference in number of colonies in various groups. To determine significant difference between individual groups, a pairwise analysis of variables was performed using the Duncan multiple range test. Means with different superscript letters (a, b, and c) indicate significant difference at P < 0.001 between groups. (C) Parental epithelial cells, primary mammospheres, secondary mammospheres, and tertiary mammospheres were trypsinized, and ALDH-expressing (ALDH+) cell population (%) in mammospheres was determined by flow cytometry. (D) Representative images of co-immuno-staining of MCF10A (10A), NB20, NB/T-20, and NB/G-20 primary mammospheres with PE-conjugated CD44-specific antibody and FITC-conjugated CD24-specific antibody. Bars, 100 μm; magnification, 400X. Arrowheads indicate CD44+/CD24− cells. (E) The relative intensity of CD44 to CD24 (CD44/CD24) in mammospheres detected in 2D was analyzed by ImageJ, the level set in control MCF10A mammospheres as 1 (X, arbitrary unit). (F) Primary mammospheres were trypsinized, cells were incubated with PE-conjugated CD44-specific antibody and FITC-conjugated CD24-specific antibody, and CD44+/CD24− cell population (%) was determined by flow cytometry. Columns, mean of triplicates; bars, SD. All results are representative of at least three independent experiments. The Student t test was used to analyze statistical significance, indicated by * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001; α levels were adjusted by the Simes method.

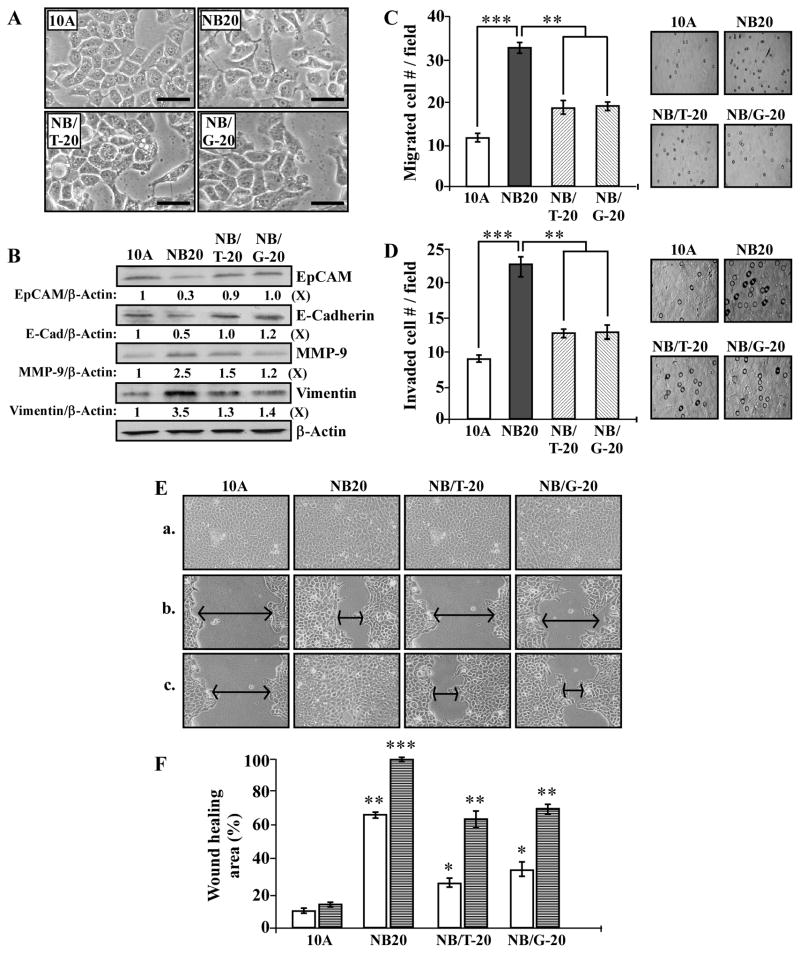

3.6. GTC and GSPE suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced EMT-associated properties and markers

Using EMT-associated cell morphology, markers, and properties as targeted endpoints, we investigated the activity of GTC and GSPE in suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced cellular carcinogenesis. As shown in Fig. 6A, mesenchymal-like cell morphology in NB20 cultures was not detected in NB/T-20 and NB/G-20 cultures. Expression of E-Cadherin and EpCAM was reduced in NB20 cells but not in NB/T-20 and NB/G-20 cells, and increases in MMP-9 and Vimentin in NB20 cells were reversed in NB/T-20 and NB/G-20 cells (Fig. 6B). In addition, the EMT-associated properties of increased cell migration (Fig. 6C), invasion (D), and mobility (E and F) acquired by NB20 cells were reversed in NB/T-20 and NB/G20 cells. Exposure of MCF10A cells to GTC or GPSE alone did not result in any detectable changes in these properties (data not shown). These results indicate that non-cytotoxic GTC and GSPE were able to protect epithelial cells from developing NNK- and B[a]P-induced EMT-associated morphological features, markers, and properties.

Fig. 6.

GTC and GSPE suppression of NNK- and B[a]P-induced EMT-associated properties. (A) Representative morphological features of MCF10A (10A), NB20, NB/T-20, and NB/G-20 cells. Bars, 100 μm; magnification, 400X. (B) Cell lysates were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using specific antibodies to detect levels of EpCAM, E-Cadherin, MMP-9, and Vimentin, with β-Actin as a control, and these levels were quantified by densitometry. The levels of EpCAM, E-Cadherin, MMP-9, and Vimentin were calculated by normalizing with the level of β-Actin and the level set in 10A cells (lane 1) as 1 (X, arbitrary unit). (C) Cellular migratory and (D) invasive activities were determined by counting the numbers of cells translocated through a polycarbonate filter without or with coated Matrigel, respectively, in 10 arbitrary visual fields. Panels show representative fields of migrated and invasive cells determined in (C) and (D). (E) Cellular acquisition of increased mobility was determined by wound healing assay. Cells were seeded in CM medium and grown to confluence (a); then, a linear area of cell layer was removed from each culture with a 23-gauge needle to produce wounded cultures, which were examined (magnification, 100X) 6 (b) and 20 hours (c) afterward. Arrows indicate width of wounded areas. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (F) To quantitatively measure cell mobility detected in (E), the area not healed by the cells was subtracted from the total area of the initial wound to calculate the wound healing area (%) at intervals of 6 (white columns) and 20 hours (striated columns). Columns, mean of triplicates; bars, SD. The Student t test was used to analyze statistical significance, indicated by * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001; α levels were adjusted by the Simes method.

Discussion

Cumulative exposures of non-cancerous human breast epithelial MCF10A to the carcinogens NNK and B[a]P, at physiologically-achievable concentrations, result in progression of cellular carcinogenesis to pre-malignant stages. This progression is measured by cellular acquisition of progressively-increased degrees of cancer-associated properties in an exposure-dependent manner, without the acquisition of tumorigenicity [11–16]. Although cellular acquisition of tumorigenicity is regarded as the gold standard for validating cell malignancy, many human cancer cells are not tumorigenic, such as urinary bladder cancer J82 cells [45]. Thus, using additional cancer-associated properties as measurable targeted endpoints should be seriously considered in studying cellular carcinogenesis progression and intervention of cellular carcinogenesis.

In this report, we presented results to reveal the values of acquisition of stem-like cell properties as well as EMT-associated markers and properties in measuring chronic induction of cellular carcinogenesis. Epithelial cells chronically exposed to NNK and B[a]P increasingly acquired stem-like cell properties of mammosphere formation and increased populations of ADLH-positive and CD44+/CD24− stem-like cells in mammospheres. The ability of carcinogen-exposed epithelial cells to develop mammospheres in serum-free, non-adherent cultures may be related to their combined abilities of reduced dependence on growth factors and anchorage-independent growth. The ability of carcinogenic epithelial cells to produce increased stem-like cell populations in mammospheres may be mediated by the EMT program, as indicated by many studies [40,59,64]. Our results revealed that the EMT-associated properties of mesenchymal morphology, cell migration, invasion, and mobility, as well as the EMT-associated markers of losing E-Cadherin and EpCAM and gaining MMP-9 and Vimentin were also increasingly acquired by epithelial cells chronically exposed to NNK and B[a]P. Accordingly, this exposure resulted in induction of the EMT program in epithelial cells, which in turn, supported development of mammospheres and an increase in stem-like cell population. Although cumulative exposures to NNK and B[a]P for 20 cycles failed to induce cellular acquisition of stem-like cell and EMT-associated properties to comparable levels acquired by tumorigenic, malignant MCF10A-Ras cells, the increased degrees of these properties acquired by the non-tumorigenic, pre-malignant NNK- and B[a]P-exposed cells clearly revealed carcinogenesis progression in an exposure cycle-dependent manner. Stem-like cells have been postulated to play important roles in not only malignant but also pre-malignant stages of cancer development [33–35]. Accordingly, NNK- and B[a]P-induced pre-malignant epithelial cells may have acquired pre-malignant stem-like cell properties, and pre-malignant stem-like cells may not be tumorigenic to immune-deficient animals. Cancer stem-like cells have also been postulated to play an important role in recurrent cancers after chemotherapy [65]. Thus, it is important to consider cellular acquisition of stem-like cell and EMT-associated properties and markers as new targeted endpoints in measuring progression and intervention of carcinogenesis. However, the mechanisms for carcinogen-induced stem-like cell properties and EMT-associated properties and markers remain to be determined.

For the first time, we demonstrated the activity of non-cytotoxic dietary green tea and grape seed extracts in suppression of stem-like cell properties and EMT-associated properties and markers induced by long-term exposure to NNK and B[a]P at a physiologically-achievable dose. Previously, we showed that GTC and GSPE, at a non-cytotoxic concentration of 40 μg/ml, effectively blocked NNK- and B[a]P-induced acquisition of the cancer-associated properties of reduced dependence on growth factors, anchorage-independent growth, and acinar-conformational disruption [11–15]. Here, we revealed that co-exposure to GTC and GSPE was effective in suppressing cellular acquisition of increased abilities of mammosphere formation, stem-like cell population, cell migration, invasion, and mobility induced by long-term exposure to NNK and B[a]P. The activity of dietary GTC and GSPE in protecting epithelial cells from acquiring stem-like cell and EMT-associated properties prevented epithelial cells from producing stem-like and mesenchymal cells. GTC and GSPE suppression of cellular acquisition of stem-like cell- and EMT-associated properties was indicated by reduction of the increased ADLH-positive and CD44+/CD24− cell populations and reversal of changes in expression of E-Cadherin, EpCAM, MMP-9, and Vimentin. However, whether dietary GTC and GSPE are able to protect mammary tissues from acquiring carcinogen-induced stem-like cell and EMT-associated properties to reduce the risk of invasive tumors, indicated by suppression of stem-like cell- and EMT-associated markers, remains to be studied.

GTC (Polyphenon-60) contains approximately 60% catechins, and it also contains 10% minor flavanols, 20% polymeric flavonoids, and other minor components [66]. Volatile fractions of tea contain more than 600 different molecules, including carbohydrates, caffeine, adenine, gallic acids, tannins, gallotannins, quercetin glycosides, carotenoids, tocopherols, vitamins (A, K, B, C), and small amounts of aminophylline [67]. Catechins are the most widely studied anti-cancer agents in green tea [68]. Only a few other green tea components, such as caffeine [69] and vitamin D [70], have been shown to exhibit anti-cancer activities. Similarly, GSPE contains 74% proanthocyanidins as well as flavonols, flavan-3-ols, anthocyanins, stilbenes, sugar, organic acid, and amino acid [71,72]; however, only proanthocyanidins are shown to have anti-cancer activities. Whether other components in GTC and GSPE, besides catechins and proanthocyanidins, may exhibit potent anticancer activities remains to be determined.

Our model presents a unique feature in that it is able to determine breast cell carcinogenesis progression chronically induced by cumulative exposures to carcinogens at a physiologically-achievable dose. Using our model, we demonstrated that cellular carcinogenesis was accompanied by acquisition of stem-like cell and EMT-associated properties and markers. These measurable properties and markers should be considered as new cancer-associated properties in studies of breast cell carcinogenesis and may serve as new targeted endpoints in detection of carcinogenesis progression. Thus, our system provides a platform equipped with measurable targeted endpoints to identify preventive agents effective in suppression of cellular carcinogenesis induced by long-term exposure to carcinogens. NNK and B[a]P are recognized as potent environmental carcinogens in the development of pulmonary cancers [4,17]. Although NNK and B[a]P may not induce tumorigenic carcinogenesis of breast cells, they induce cellular acquisition of various cancer-associated properties, including stem-like and EMT-associated properties; therefore, their carcinogenic roles in breast cancer development, even in pre-malignant stages, should be recognized. Indeed, prevention of cellular carcinogenesis at various stages is the key to reduce the risk of cancer development, and effective intervention of pre-malignant carcinogenesis is highly important in cancer prevention. It is important to consider the use of non-cytotoxic, dietary GTC and GSPE in early prevention of pre-malignant cell carcinogenesis in sporadic breast cancer development associated with long-term exposure to low doses of environmental carcinogens. Furthering technology of using dietary GTC and GSPE in prevention of pre-malignant cell carcinogenesis, especially to intervene in the acquisition of stem-like cell and EMT-associated properties, may allow us to overcome a current obstacle in control of cancer stem-like cell resistance to therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported by a grant from the University of Tennessee, College of Veterinary Medicine, Center of Excellence in Livestock Diseases and Human Health [to H-C.R.W.]; and the National Institutes of Health [CA125795 and CA129772 (H-C.R.W.)].

We are grateful to Ms. M. Bailey for textual editing of the manuscript. We thank Ms. DJ Trent for technique support in flow cytometric analysis of CD44+ and CD24+ cell populations. We thank Dr. J Dunlap for technique support for the use of confocal epifluorescence microscopes in immunofluorescence detection of CD44+ and CD24+ cells.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- B[a]P

benzo[a]pyrene

- CM

complete MCF10A

- DEAB

diethylaminobenzaldehyde

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GSPE

grape seed proanthocyanidin extract

- GTC

green tea catechins

- LM

low mitogen

- NNK

4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- PE

phycoerythrin

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Guengerich FP. Metabolism of chemical carcinogens. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:345–351. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelloff GJ, Hawk ET, Sigman CC. Cancer chemoprevention. Vol. 2. Totowa: Human Press; New Jersey: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBruin LS, Josephy PD. Perspectives on the chemical etiology of breast cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;1:119–128. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecht SS. Tobacco smoke carcinogens and breast cancer. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. 2002;39:119–126. doi: 10.1002/em.10071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roukos DH, Murray S, Briasoulis E. Molecular genetic tools shape a roadmap towards a more accurate prognostic prediction and personalized management of cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:308–312. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.3.3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta RG. Experimental basis for the prevention of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1275–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecht SS. Tobacco smoke carcinogens and lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1194–1210. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.14.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obana H, Hori S, Kashimoto T, Kunita N. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human fat and liver. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1981;27:23–27. doi: 10.1007/BF01610981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hecht SS, Carmella G, Chen M, Dor Koch JF, Miller AT, Murphy SE, Jensen JA, Zimmerman CL, Hatsukami DK. Quantitation of urinary metabolites of a tobacco-specific lung carcinogen after smoking cessation. Cancer Res. 1999;59:590–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Besaratinia A, Maas, Brouwer EM, Moonen EJ, De Kok TM, Wesseling GJ, Loft S, Kleinjans JC, Van Schooten FJ. A molecular dosimetry approach to assess human exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in pubs. Carcinogenesis. 2003;23:1171–1176. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.7.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mei J, Hu H, McEntee M, Song P, Wang HCR. Transformation of noncancerous human breast epithelial cell MCF10A induced by the tobacco-specific carcinogen NNK. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;79:95–105. doi: 10.1023/a:1023326121951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siriwardhana N, Wang HCR. Precancerous carcinogenesis of human breast epithelial cells by chronic exposure to benzo[a]pyrene. Mol Carcinogenesis. 2008;47:338–348. doi: 10.1002/mc.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siriwardhana N, Choudhary S, Wang HCR. Precancerous model of human breast epithelial cells induced by the tobacco-specific carcinogen NNK for prevention. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:427–441. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song X, Siriwardhana N, Rathore K, Wang HCR. Grape seed proanthocyanidin suppression of breast cell carcinogenesis induced by chronic exposure to combined 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and benzo[a]pyrene. Mol Carcinogenesis. 2010;49:450–463. doi: 10.1002/mc.20616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathore K, Choudhary S, Odoi A, Wang HCR. Green tea catechin intervention of reactive oxygen species-mediated ERK pathway activation and chronically induced breast cell carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:174–183. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rathore K, Wang HCR. Green tea catechin extract in intervention of chronic breast cell carcinogenesis induced by environmental carcinogens. Mol Carcinogenesis. 2012;51:280–289. doi: 10.1002/mc.20844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hecht SS. Recent studies on mechanisms of bioactivation and detoxification of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), a tobacco specific lung carcinogen. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1996;26:163–181. doi: 10.3109/10408449609017929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hecht SS, Hatsukami DK, Bonilla LE, Hochalter JB. Quantitation of 4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butanoic acid and enantiomers of 4-hydroxy-4-(3-pyridyl)butanoic acid in human urine, A substantial pathway of nicotine metabolism. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:172–179. doi: 10.1021/tx980214i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chhabra SK, Anderson LM, Perella C, Desai D, Amin S, Kyrtopoulos SA, Souliotis VL. Coexposure to ethanol with N-nitrosodimethylamine or 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone during lactation of rats, marked increase in O(6)-methylguanine-DNA adducts in maternal mammary gland and in suckling lung and kidney. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;169:191–200. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohnishi T, Fukamachi K, Ohshima Y, Jiegou X, Ueda S, Iigo M, Takasuka N, Naito A, Fujita K, Matsuoka Y, Izumi K, Tsuda H. Possible application of human c-Ha-ras proto-oncogene transgenic rats in a medium-term bioassay model for carcinogens. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:436–443. doi: 10.1080/01926230701302541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavalieri E, Rogan E, Sinha D. Carcinogenicity of aromatic hydrocarbons directly applied to rat mammary gland. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00390478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li A, Zhang W, Sahin AA, Hittelman WN. DNA adducts in normal tissue adjacent to breast cancer, a review. Cancer Detect Prev. 1999;23:454–462. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1500.1999.99059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rundle A, Tang D, Hibshoosh H, Estabrook A, Schnabel F, Cao W, Grumet S, Perera FP. The relationship between genetic damage from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in breast tissue and breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1281–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin H. Synergistic mechanisms in carcinogenesis by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and by tobacco smoke, a bio-historical perspective with updates. Carcinogenesis. 2011;22:1903–1930. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds P, Hurley S, Goldberg DE, Anton-Culver H, Bernstein L, Deapen D, Horn-Ross PL, Peel D, Pinder R, Ross RK, West D, Wright WE, Ziogas A. Active smoking, household passive smoking, and breast cancer, evidence from the California Teachers Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:29–37. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson KC, Miller AB, Collishaw NE, Palmer JR, Hammond SK, Salmon AG, Cantor KP, Miller MD, Boyd NF, Millar J, Turcotte F. Active smoking and secondhand smoke increase breast cancer risk, the report of the Canadian Expert Panel on Tobacco Smoke and Breast Cancer Risk (2009) Tobacco Control. 2011;20:e2. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.035931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds P, Goldberg D, Hurley S, Nelson DO, Largent J, Henderson KD, Bernstein L. Passive smoking and risk of breast cancer in the California teachers study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3389–3398. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwasaki M, Tsugane S. Risk factors for breast cancer, epidemiological evidence from Japanese studies. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1607–1614. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadri G, Mahjub H. Passive or active smoking, which is more relevant to breast cancer. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:254–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kavanagh KT, Hafer LJ, Kim DW, Mann KK, Sherr DH, Rogers AE, Sonenshein GE. Green tea extracts decrease carcinogen-induced mammary tumor burden in rats and rate of breast cancer cell proliferation in culture. J Cell Biochem. 2001;82:387–398. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roomi MW, Roomi NW, Ivanov V, Kalinovsky T, Niedzwiecki A, Rath M. Modulation of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea induced mammary tumors in Sprague- Dawley rats by combination of lysine, proline, arginine, ascorbic acid and green tea extract. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:291–295. doi: 10.1186/bcr989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim H, Hall P, Smith M, Kirk M, Prasain JK, Barnes S, Grubbs C. Chemoprevention by grape seed extract and genistein in carcinogen-induced mammary cancer in rats is diet dependent. J Nutr. 2004;134:3445S–3452S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3445S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farnie G, Clarke RB. Mammary stem cells and breast cancer-role of Notch signalling. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:169–175. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville E, Ginestier C, Dontu G, Birnbaum D, Wicha MS. Cancer stem cells in breast, current opinion and future challenges. Pathobiology. 2008;75:75–84. doi: 10.1159/000123845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kakarala M, Wicha MS. Implications of the cancer stem-cell hypothesis for breast cancer prevention and therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2813–2820. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Polyak K, Brisken C, Yang J, Weinberg RA. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipton A, Klinger I, Paul D, Holley RW. Migration of mouse 3T3 fibroblasts in response to a serum factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;11:2799–2801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.11.2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choudhary S, Sood S, Donnell RL, Wang HCR. Intervention of human breast cell carcinogenesis chronically induced by 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:876–885. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albini A, Iwamoto Y, Kleinman HK, Martin GR, Aaronson SA, Kozlowski JM, McEwan RN. A rapid in vitro assay for quantitating the invasive potential of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3239–3245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, Wicha MMS. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ginestier A, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Jacquemier J, Viens P, Kleer CG, Liu S, Schott A, Hayes D, Birnbaum D, Wicha MS, Dontu G. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duong MT, Akli S, Wei C, Wingate HF, Liu W, Lu Y, Yi M, Mills GB, Hunt KK, Keyomarsi K. LMW-E/CDK2 deregulates acinar morphogenesis, induces tumorigenesis, and associates with the activated b-Raf-ERK1/2-mTOR pathway in breast cancer patients. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.ImageJ. Image processing and analysis in Java. http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/

- 44.Simes RJ. An improved Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1986;73:751–754. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marshall CJ, Franks LM, Carbonell AW. Markers of neoplastic transformation in epithelial cell lines derived from human carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;58:1743–1751. doi: 10.1093/jnci/58.6.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanahan A, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campisi J, Morreo G, Pardee AB. Kinetics of G1 transit following brief starvation for serum factors. Exp Cell Res. 1984;152:459–466. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(84)90647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larsson O, Zetterberg A, Engstrom W. Consequences of parental exposure to serum-free medium for progeny cell division. J Cell Science. 1985;75:259–268. doi: 10.1242/jcs.75.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valentijn AJ, Zouq N, Gilmore AP. Anoikis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:421–425. doi: 10.1042/BST0320421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reddig PJ, Juliano RL. Clinging to life, cell to matrix adhesion and cell survival. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:425–439. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Datta S, Hoenerhoff MJ, Bommi P, Sainger R, Guo WJ, Dimri M, Band H, Band V, Green JE, Dimri GP. Bmi-1 cooperates with H-Ras to transform human mammary epithelial cells via dysregulation of multiple growth-regulatory pathways. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10286–10295. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choudhary S, Rathore K, Wang HCR. FK228 and oncogenic H-Ras synergistically induce Mek1/2 and Nox-1 to generate reactive oxygen species for differential cell death. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21:831–840. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32833ddba6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cioce M, Gherardi S, Viglietto G, Strano S, Blandino G, Muti P, Ciliberto G. Mammosphere-forming cells from breast cancer cell lines as a tool for the identification of CSC-like- and early progenitor-targeting drugs. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2878–2887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Engelmann K, Shen H, Finn OJ. MCF7 side population cells with characteristics of cancer stem/progenitor cells express the tumor antigen MUC1. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2419–2426. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Iovino F, Wicinski J, Cervera N, Finetti P, Hur MH, Diebel ME, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Viens P, Xerri L, Bertucci F, Stassi G, Dontu G, Birnbaum D, Wicha MS. Breast cancer cell lines contain functional cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity and a distinct molecular signature. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1302–1313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JM, Dedhar S, Kalluri R, Thompson EW. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition, new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:973–981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu M, Casimiro MC, Wang C, Shirley LA, Jiao X, Katiyar S, Ju X, Li Z, Yu Z, Zhou J, Johnson M, Fortina P, Hyslop T, Windle JJ, Pestell RG. p21CIP1 attenuates Ras- and c-Myc-dependent breast tumor epithelial mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like gene expression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19035–19039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910009106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wijnhoven BP, Dinjens WN, Pignatelli M. E-cadherin-catenin cell-cell adhesion complex and human cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87:992–1005. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Litvinov SV, Balzar M, Winter MJ, Bakker HA, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Prins F, Fleuren GJ, Warnaar SO. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (Ep-CAM) modulates cell-cell interactions mediated by classic cadherins. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1337–1348. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagase H, Woessner JF. Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21491–21494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vuoriluoto K, Haugen H, Kiviluoto S, Mpindi JP, Nevo J, Gjerdrum C, Tiron C, Lorens JB, Ivaska J. Vimentin regulates EMT induction by Slug and oncogenic H-Ras and migration by governing Axl expression in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:1436–1448. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dimri G, Band H, Band V. Mammary epithelial cell transformation, insights from cell culture and mouse models. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:171–179. doi: 10.1186/bcr1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Mejia EG, Ramirez-Mares MV, Puangpraphant S. Bioactive components of tea: cancer, inflammation and behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:721–731. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jayabalan R, Subathradevi B, Marimuthu S, Sathishkumar M, Swaminathan K. Changes in free-radical scavenging ability of kombucha tea during fermentation. Food Chem. 2008;109:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thakur VS, Gupta K, Gupta S. The chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic potentials of tea polyphenols. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:191–199. doi: 10.2174/138920112798868584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sabisz M, Skladanowski A. Modulation of cellular response to anticancer treatment by caffeine: inhibition of cell cycle checkpoints, DNA repair and more. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2008;9:325–336. doi: 10.2174/138920108785161497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Norton R, O’Connell MA. Vitamin D: potential in the prevention and treatment of lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cavaliere C, Foglia P, Gubbiotti R, Sacchetti P, Samperi R, Laganà A. Rapid-resolution liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry for determination and quantitation of polyphenols in grape berries. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:3089–3099. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shiraishi M, Fujishima H, Chijiwa H. Evaluation of table grape genetic resources for sugar, organic acid, and amino acid composition of berries. Eupytica. 2010;174:1–13. [Google Scholar]