Abstract

Objective

Prior work has showed that nigral neuron density is related to the severity of parkinsonism proximate to death in older persons without a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD). We tested the hypothesis that neuron density in other brainstem aminergic nuclei is also related to the severity of parkinsonism.

Design

We studied brain autopsies from 125 deceased older adults without PD enrolled in the Memory and Aging Project, a clinical-pathologic investigation. Parkinsonism was assessed with a modified version of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). We measured neuron density in the substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe; and postmortem indices of Lewy body Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular pathologies.

Results

Mean age at death was 88.0 and global parkinsonism was 14.8 (SD=9.50). In a series of regression models which controlled for demographics and neuron density in the substantia nigra, neuron density in the locus coeruleus (Estimate, −0.261, S.E., 0.117, p=0.028) but not in the ventral tegmental area or dorsal raphe was associated with the severity of global parkinsonism proximate to death. These findings were unchanged in models which controlled for post-mortem interval, whole brain weight and other common neuropathologies including Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body pathology and cerebrovascular vascular pathologies.

Conclusion

In older adults without a clinical diagnosis of PD, neuron density in locus coeruleus nuclei is associated with the severity of parkinsonism and may contribute to late-life motor impairments.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Parkinsonism, Substantia Nigra, Locus Coeruleus

INTRODUCTION

Mild parkinsonian signs may be present in up to half of community-dwelling older persons without Parkinson’s disease (PD) by age 85 and are associated with a wide range of adverse health outcomes. 1–4 Most information about the neuropathology underlying parkinsonian signs comes from studies of persons with PD.5 The essential neuropathology of PD includes neuronal loss of nigral melanin-pigmented dopaminergic neurons, one of several aminergic nuclei located in the brainstem, with associated Lewy body pathology.6 However, both PET scans and post-mortem studies in persons with PD demonstrate neuronal loss in other brainstem aminergic nuclei.6–8 Several reports including one from this cohort reported that nigral neuron density in older adults without PD is associated with the severity of parkinsonism. 6,9–11 However, the nigra only accounts for only a small amount of the variance of parkinsonism raising the possibility that other degeneration of other brainstem aminergic nuclei which express Lewy body pathology contribute to the severity of parkinsonism in older adults.

The current study extends prior work by examining the hypothesis that neuron density in other brainstem aminergic nuclei is related to the severity of parkinsonism using clinical and post-mortem data from 125 cases in the Memory and Aging Project without a history of PD.12 First, we examined whether neuron density in other aminergic nuclei had independent effects with parkinsonism controlling for substantia nigra neuron density. Then we examined whether these associations were attenuated when controlling for other common neuropathologies which are also associated with parkinsonism in older adults.

METHODS

Subjects

Participants were from the Memory and Aging Project approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center. Each subject signed an informed consent for annual exam and an anatomic gift act for donation of brain at the time of death.12 At the time of these analyses complete post-mortem data were available for 128 cases and 3 cases with a history of PD were excluded.

Clinical Evaluation and Assessment of Parkinsonian Signs

Participants underwent a uniform structured clinical evaluation each year that included a medical history, neurologic examination, and neuropsychological performance tests.12 Trained nurse clinicians administered a 26-item mUPDRS.13 Four previously established parkinsonian sign scores were derived and scaled from 0 to 100 and aglobal parkinsonian sign score was constructed by averaging these four scores.13 The average interval between last clinical examination and death was on average 11.1 months (SD = 11.00).

Post-Mortem Evaluation

The average postmortem interval was 6.91 hours (SD = 4.29 hours) and brains weighed 1161gm (SD=123.0 gm). A complete neuropathologic evaluation was performed as previously described.9

Aminergic Nuclei Neuron Density

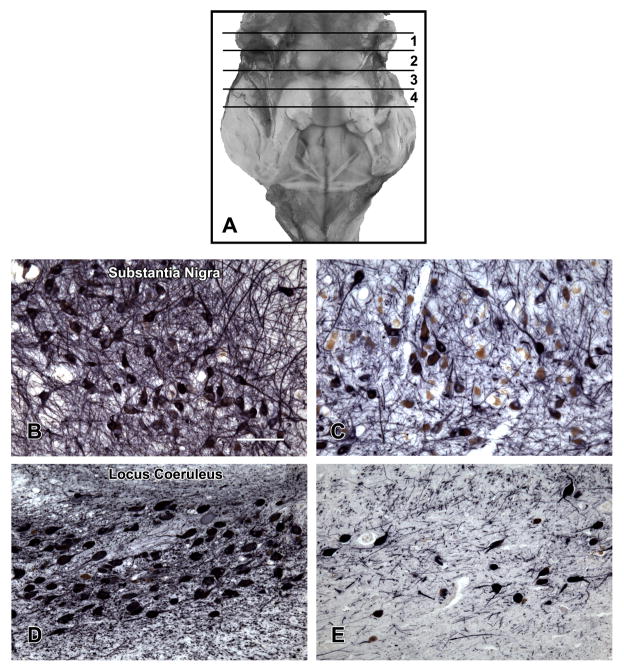

Four transverse blocks of fixed tissue were taken at the brainstem levels illustrated in Figure 1A.14 Tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin. The 6 μm sections were stained with Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and used to delineate and outline the regions of interest. We used 20 μm sections to perform immunohistochemistry with tyrosine hydroxylase (Immunostar or DAB, Hudson, WI) to identify neurons in the substantia nigra, paranigral nucleus and locus coeruleus with alkaline phosphatase as the chromogen. Serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe were identified using an anti-tryptophan hydroxylase monoclonal antibody (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) with diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. The regions of interest which were then outlined using software available on Stereo Investigator Program (MBF Biosciences, Williston, VT) attached to an Olympus BX60 microscope equipped with a motorized stage. All neurons counted in each of these 4 regions were divided by the area of the region to obtain the neuron density/μm2, the primary measure used in these analyses. Figure 1 contrast high and low neuron density in the substantia nigra (Figure 1B and 1C) and locus coeruleus (Figure 1D and 1E).

Figure 1. Locations of the Brainstem Tissue Blocks Containing Aminergic Nuclei.

A. The cerebellum has been removed to show the posterior aspect of the brain stem extending from the level of the superior colliculi rostrally to the obex caudally. The locations of the tissue blocks from which neuron density of substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe aminergic nuclei were obtained are shown. The black lines indicate the caudal aspect of the block. The first block was taken from the midbrain at the level of the exiting 3rd nerve fibers, and included (part of) the substantia nigra and paranigral nucleus of the ventral tegmental area. The second block at the level of the trochlear nucleus and the decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncles contained the rostral dorsal raphe nucleus. The third block, adjacent to the 2nd block, included the caudal dorsal raphe nucleus and the rostral locus coeruleus nuclei. The fourth block contained the main body of the locus coeruleus. B and C contrast low and high neuron density in the substantia nigra. D and E contrast low and high neuron density in the locus coeruleus.

Other Common Neuropathologies

Lewy bodies were identified in 6 μm sections with a mouse phosphorylated alpha-synuclein antibody (Wako Chemicals USA Inc, Richmond, VA) using alkaline phosphatase as the chromogen.9 The presence of Lewy bodies in any of these sites was considered sufficient for Lewy body pathology positivity. A composite measure of AD pathology was based on counts of neuritic plaques, diffuse plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles visualized with Bielschowsky silver stain.9 PHFtau was labeled with an antibody specific for phosphorylated tau (AT8, Innogenetics, San Ramon, CA, 1:1000) and its overall burden was quantified.15 Post-mortem indices of cerebrovascular pathologies included macroinfarcts, microinfarcts, and arteriolosclerosis were collected.9 The presence or absence of macroinfarcts and microinfarcts was used as a covariate in these analyses.

Statistical Analysis

The global parkinsonian sign score, the gait score and bradykinesia had positively skewed distributions and were subjected to a square root transformation, and the transformed scores were used as outcome variables in all analyses. Rigidity, and tremor were relatively infrequent and so were treated as present or absent in analyses. We used Spearman correlations to examine the interrelationship between neuron densities in the 4 aminergic nuclei. In our primary analyses, we employed separate regression analyses controlling for age, sex and education, to document the association of neuron density in the aminergic nuclei with global parkinsonism. A similar analytic approach was employed to examine the association of neuron density with each of the four individual parkinsonian signs. Age and neuron density in the four aminergic nuclei were standardized to facilitate comparison of parameter estimate in these analyses. We used linear regression models to examine parkinsonian gait and bradykinesia and logistic regressions for presence or absence of tremor and rigidity. Model assumptions of linearity, normality, independence of errors, and homoscedasticity of errors were examined graphically and analytically and were adequately met. All analyses were carried out using SAS/STAT software Version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) on a Hewlett Packard ProLiant ML350 server running LINUX. 16

RESULTS

Summary of Parkinsonian Signs and Aminergic Nuclei Neuron Density

These analyses included 125 cases. Clinical characteristics at their last visit and post-mortem indices are included in Table 1. Global parkinsonism was associated with age and education but not with sex (Table 2, Model 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Post-Mortem Indices (N=125)

| Variable | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at Death (years) | 88.0 (5.75) |

| Sex (female) | 84 (67.2%) |

| White, non-Hispanic (N, %) | 121 (96.8%) |

| Education (years) | 14.5 (2.64) |

| Last Mini-mental Status (max 30) | 24.6 (6.36) |

| GLOBAL PARKINSONISM (max 100) | 14.8 (9.50) |

| Parkinsonian gait (max 100) | 36.0 (20.48) |

| Rigidity (max 100) | 7.4 (13.89) |

| Tremor (max 100) | 2.6 (4.13) |

| Bradykinesia (max 100) | 16.5 (13.12) |

| POST-MORTEM INDICES | |

| Aminergic Nuclei (neuron density/μm2) | |

| Substantia Nigra | 31.2 (10.10) |

| Ventral Tegmental Area | 95.5 (44.35) |

| Dorsal Raphe | 102.5(25.56) |

| Locus Coeruleus | 41.1 (14.71) |

| Lewy body pathology | 27 (22.2%) |

| Alzheimer’s pathology (summary) | 0.56 (0.50) |

| Tau tangles | 5.3 (5.77) |

| Chronic macroinfarct | 35 (28.0%) |

| Chronic microinfarct | 26 (20.8%) |

| Arteriolosclerosis (moderate-severe) | 50 (40.0%) |

Table 2.

Aminergic Nuclei Neuron Density and Global Parkinsonism Score *

| Term | Demographic | Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | 0.083 | 0.109 | 0.100 | 0.117 | 0.167 | 0.138 |

| Age | 0.268 (0.108,0.014) | 0.244 (0.107,0.024) | 0.242 (0.113,0.035) | 0.265 (0.111,0.018) | 0.223 (0.110, 0.046) | 0.203 (0.119,0.091) |

| Sex | −0.017 (0.243,0.944) | −0.006 (0.242,0.979) | 0.052 (0.250,0.836) | 0.001 (0.249,0.998) | 0.049 (0.242,0.840) | 0.072 (0.253,0.775) |

| Education | 0.113 (0.043,0.011) | 0.094 (0.043,0.033) | 0.096 (0.046,0.038) | 0.086 (0.044,0.052) | 0.090 (0.043,0.037) | 0.091 (0.045,0.049) |

| Substantia Nigra | −0.273 (0.113,0.018) | −0.327 (0.136,0.018) | −0.293 (0.113,0.011) | −0.265 (0.112,0.020) | −0.298 (0.136,0.031) | |

| Ventral Tegmental Area | 0.020 (0.126,0.872) | 0.011 (0.127,0.931) | ||||

| Dorsal Raphe | −0.078 (0.117,0.504) | 0.012 (0.128,0.928) | ||||

| Locus Coeruleus | −0.261 (0.117,0.028) | −0.273 (0.130,0.039) |

The outcome for all models was global parkinsonian score proximate to death. Estimated from a series of regression models [Estimate (Standard Error, p Value)].

Neuron densities in the aminergic nuclei (Table 1) were highly correlated with pairwise correlations between r=0.66 to r=0.84. Neuron density in the substantia nigra was highly associated with neuron density in the ventral tegmental area (r=0.84, p<0.001); dorsal raphe (r=0.81, p<0.001) and locus coeruleus (r=0.84, p<0.001). Neuron density in the ventral tegmental area was related to neuron density in the dorsal raphe (r=0.76, p<0.001) and locus coeruleus (r=0.66, p<0.001). Neuron density in the dorsal raphe was correlated with neuron density in the locus coeruleus (r=0.69, p<0.001).

Aminergic Nuclei Neuron Density and Global Parkinsonism

We examined global parkinsonism as a function of neuron density in each of the other aminergic nuclei in separate regression analyses. We used the adjusted R2 to convey the strength of the association. The core model which included terms for age, sex, education and substantia nigra neuron density explained 10.9% of the variance of global parkinsonism (Table 2, Model A). Neuron density in the locus coeruleus showed an independent association with global parkinsonism and explained an additional 6% of the variance of global parkinsonism as compared to the core model (Table 2, Model D versus Model A). By contrast, neuron density in the ventral tegmental area and dorsal raphe were not related to the level of global parkinsonism (Table 2, Models B and C). In a final model, neuron density in locus coeruleus remained associated with global parkinsonism when controlling for demographics and neuron density in the substantia nigra, VTA and dorsal raphe in a single model (Table 2, Model E).

Neuron density in locus coeruleus remained associated with parkinsonism when controlling for the post-mortem interval (Estimate; −0.262, S.E., 0.117, p=0.027) and the weight of brains at the time of autopsy (Estimate, −0.246, S.E., 0.117, p=0.037).

Aminergic Nuclei Neuron Density, Common Neuropathologies and Global Parkinsonism

The assessment of both Lewy body pathology and neuronal loss in the aminergic nuclei is essential for the post-mortem staging of PD.6 While none of the cases in this study had a clinical diagnosis of PD, we examined whether neuron density in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus remained associated with global parkinsonism when we controlled for the presence of Lewy body pathology. The estimates for the associations of neuron density in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus with global parkinsonism remained unchanged after adding a term for Lewy body pathology (Table 3, Model B versus Model A)

Table 3.

Locus Coeruleus Neuron Density, Common Neuropathologies and Global Parkinsonism Score *

| Term | Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E | Model F | Model G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | 0.167 | 0.174 | 0.177 | 0.200 | 0.164 | 0.192 | 0.231 |

| Substantia Nigra | −0.265 (0.112,0.020) | −0.235 (0.114,0.041) | −0.234 (0.113,0.042) | −0.244 (0.113,0.033) | −0.261 (0.112,0.022) | −0.231 (0.0112.041) | −0.160 (0.115,0.168) |

| Locus Coeruleus | −0.261 (0.117,0.028) | −0.229 (0.119,0.057) | −0.239 (0.118,0.044) | −0.264 (0.117,0.026) | −0.276 (0.118,0.021) | −0.295 (0.117,0.013) | −0.256 (0.120,0.036) |

| Lewy body pathology | 0.391 (0.280,0.167) | 0.452 (0.281,0.110) | |||||

| Alzheimer’s disease pathology | 0.167 (0.108,0.127) | 0.083 (0.113,0.467) | |||||

| Macroinfarcts | 0.321 (0.247,0.197) | 0.283 (0.256,0.283) | |||||

| Microinfarcts | 0.330 (0.281,0.244) | −0.151 (0.291,0.604) | |||||

| Arteriolosclerosis | 0.262 (0.125,0.038) | 0.256 (0.126,0.044) |

The outcome for all models was global parkinsonian score proximate to death. Estimated from a series of regression models adding terms for different post-mortem indices [Estimate, Standard Error, p Value). All these models adjusted for age, sex, and education which are not shown in this table.

Prior work suggests that global parkinsonism is associated with other common neuropathologies.9 Therefore we examined we examined whether the association of neuron density in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus and global parkinsonism was attenuated when we controlled for the presence of a composite measure of AD pathology, macroinfarcts, microinfarcts and arteriolosclerosis. The estimates for the associations of both substantia nigra and locus coeruleus with the severity of parkinsonism proximate to death remained unchanged when controlling for each of these pathologies (Table 3, Models C, D, E and F compared to Model A).

In further analyses, we added terms to model B (Table 3) to control for CERAD score [2.5 (SD=1.11)] and the overall burden of tau tangles. Adding these terms did not affect the association of substantia nigra and locus coeruleus neuron density with parkinsonism (results not shown).

In a final model, which included all the pathologies in a single model the association of neuron density in the substantia nigra and parkinsonism was attenuated and no longer significant. In contrast, neuron density in the locus coeruleus remained associated with parkinsonism (Table 3, Model G).

Aminergic Nuclei Neuron Density and Individual Parkinsonian Signs

Next we examined the association of neuron density in aminergic nuclei and the individual parkinsonian signs controlling for age, sex, education and substantia nigra neuron density. Neuron density in the locus coeruleus showed a trend for an association with (Estimate −0.390, S.E., 0.203, p=0.057) the level of bradykinesia proximate to death, but not to parkinsonian gait, rigidity or tremor (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

This clinical-autopsy study of 125 older adults without PD, extends prior work which focused on nigral neuron density by examining the association of neuron density in 3 additional aminergic nuclei with the severity of parkinsonism proximate to death. Although neuron density in these aminergic nuclei was highly correlated, only neuron density in the locus coeruleus showed an independent association with the severity of global parkinsonism and bradykinesia proximate to death. This association persisted even when we controlled for AD and Lewy body pathology and several cerebrovascular pathologies that have been reported to be associated with the severity of parkinsonism. These findings suggest that neuron density in the locus coeruleus contributes to the development of mild parkinsonian signs in older adults without PD.

Mild parkinsonian signs are common affecting up to 50% of older adults by age 85 and associated with a wide range of adverse health outcomes.1–4 These impairments can be expected to affect an increasing number of older adults given the projected aging of our population, anticipated to grow from 40 million persons over age 65 in the US to more than 70 million persons over 65 in 2030.17 With a public health problem of this magnitude, it is essential to understand its underlying neuropathology to facilitate the development of effective interventions. Few studies have investigated the neuropathology of parkinsonian signs in older persons without PD. An earlier study reported that neuronal loss occurs in older persons with incidental Lewy bodies and controls without PD, but did not assess signs of parkinsonism. 11 Several recent studies including one study in the current cohort, reported that nigral neuronal loss is associated with the severity of parkinsonian signs in older adults without clinical PD but only accounted for a small amount of the variance of parkinsonism.9,10 These reports linking PD pathology in the substantia nigra with late-life parkinsonian signs suggest that investigations of other anatomic sites affected by Lewy body pathology might also contribute to parkinsonian signs in older persons without PD.

The relationship between idiopathic PD and late-life mild parkinsonian signs is not clear. Recent work supports the notion that Lewy body pathology accumulates throughout the nervous system over many years, although the clinical symptoms are not severe enough to warrant a clinical diagnosis of PD.8 Furthermore, there appears to be a topographic selectively of neuronal loss within affected regions.11 Neuronal loss in traditional PD is not limited to dopaminergic nigral neurons, one of several aminergic nuclei located in the brainstem. Neurotransmitters for aminergic neurons are derived from aromatic amino acids including tyrosine (precursor of dopamine) or tryptophan (precursor of serotonin). Dopamine and serotonin are synthesized in the CNS through a common enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase and in noradrenergic neurons, dopamine is the precursor for the synthesis of norepinephrine.18 Both ante-mortem PET scans and post-mortem studies demonstrate that during its course PD also affects other aminergic nuclei including noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus and serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe.6–8 The contribution of pathology in other aminergic nuclei to clinical manifestations of PD is unclear.

The current study extends prior studies of the pathologic basis of parkinsonism in older adults without PD in several important ways. First it shows that neuron density in locus coeruleus is associated with the severity of parkinsonism and bradykinesia proximate to death, in addition to nigral neuron density. While the intercorrelation of neuron density was high among the 4 aminergic nuclei examined in this study, only neuron density in the locus coeruleus showed an independent association with was the severity of parkinsonism when controlling for substantia nigra neuron density. These findings suggest that investigations of other sites in the brainstem and spinal cord which have been reported to be affected in traditional PD may also be associated with mild parkinsonian signs in older adults without PD. Additional studies employing a wider range of non-motor clinical functions which have been reported to be affected in traditional PD would be useful for determining the clinical consequences of neuron density in the dorsal raphe and ventral tegmental area. Finally, these findings support the notion that both the location within the CNS as well as the burden of PD pathology may be important determinants of the severity of clinical symptoms in older persons without a clinical diagnosis of PD.

An important finding in the current study is that locus coeruleus neuron density accounted for more of the variance of parkinsonism than neuron density of the substantia nigra (6% versus 2.5%) despite the well known link between motor symptoms and nigral pathology (Table 2 model D versus model A). Nonetheless, when considered together neuron density in the locus coeruleus and substantia nigra showed an additive effect together accounting almost 8.5 % of the variance of global parkinsonian score (Table 3 Model D ) which is about the same amount of variance accounted for by age, sex and education in a model alone (Table 2, Demographic). These findings have important translational implications since they suggest that neuron density in both the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus may be unrecognized contributors to the development of mild parkinsonian signs in older persons without PD.19–21 These data also underscore that further investigations of other non-nigral sites known to be affected in traditional PD may contribute to a fuller understanding of the pathologic substrate which underlies parkinsonian signs in older adults without a clinical diagnosis of PD.

The physiologic basis for the association between locus coeruleus neuron density and parkinsonism in the current study is uncertain. Locus coeruleus modulates the survival of nigral dopaminergic neurons and may affect symptoms in PD through modulation of nigrostriatal function.22 Further, recent studies have suggested a link between locus coeruleus and rest tremor.23 The major roles of the locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system involve arousal, attention and response to stress. For example, changes in firing of locus coeruleus neurons anticipate a wide range of behavioral changes including wake/sleep, focused attention and accurate task performances.24 These attentional functions of locus coeruleus might also account for its association with the severity of parkinsonism, especially bradykinesia, in the current study. Finally, a recent study using an adeno-associated viral vector documented that locus coeruleus cells project to the ventral horn of the spinal cord suggesting a pathway which might explain the association with motor function observed in this study.25

Our results also suggest that neuron density in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus are not the only cause of parkinsonism in old age, since Lewy body pathology and cerebrovascular pathologies measured in other brain regions were also associated with the severity of parkinsonism (Table 3). It is important to note that while these findings were statistically significant, these pathologies together with demographics explain less than 25% of the variance of parkinsonism (Table 3, Model G). There are several reasons why our study may have underestimated the contributions of these pathologies to mild parkinsonian signs in old age. First, the post-mortem indices for AD pathology were preferentially collected from traditional cognitive-related brain regions rather than motor-related cortical regions and it would be important to examine the contribution of tau tangles in the aminergic nuclei. Second other motor-related regions rostral and caudal to the substantia nigra were not examined and like the locus coeruleus are likely to make separate contributions to the severity of parkinsonism.8,26 Furthermore other known pathologies such as white matter loss were not measured. Finally it should also be noted that the link between locus coeruleus and parkinsonism might reflect regional neuronal loss in the pontine tegmentum and could be a marker for neuronal loss in other nearby structures like the pedunculopontine nucleus. Further studies are needed to replicate these findings and to determine the degree to which subclinical accumulation of other neuropathologies contribute to development of parkinsonian signs in old age.

There are several strengths to the study, including the community-based cohort with large numbers of women and men coming to autopsy following high rates of clinical follow-up and high autopsy rates. Uniform structured clinical procedures were used that included a detailed quantitative assessment of parkinsonian signs that has been widely used in other studies. Uniform structured post-mortem procedures were also used that assessed several common neuropathologies as well as several post-mortem indices of PD including brainstem aminergic nuclei. Stereology for total number of neurons in aminergic nuclei was not done in the current study. However, the approach employed allowed for high-throughput estimation of neuron density in multiple brainstem sites suitable for correlation analyses in large-scale studies. Thus, results of the current study could be confounded by age-related neuron and neuropil loss, which could variably attenuate the density values. Finally, all examiners were blinded to previous evaluations and the results of brain autopsy, and neuropathologic evaluation was performed blinded to the clinical data, reducing the potential for bias.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources For Study: Supported by the National Institute of Health grants R01AG17917, R01AG24480, R01NS079623 and K08AG034290, the Illinois Department of Public Health, and the Robert C. Borwell Endowment Fund.

We thank all the participants in the Memory and Aging Project. We also thank Traci Colvin and Tracey Nowakowski for project coordination; John Gibbons for data management; Wenqing Fan, MS for statistical programming and the staff of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Footnotes

Access to Data: Dr. Buchman and co-authors had full access to the data, have the right to publish all the data, and have had the right to obtain independent statistical analyses of the data. Dr. Buchman takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Authors Roles: Research project: Drs. Buchman, Nag Lim, Shulman, VanderHorst, Leurgans, Schneider, and Bennett were involved in the conception, organization and execution of the project. Statistical Analysis: Drs. Buchman, Leurgans and Bennett were involved in the design, execution and review of the statistical analyses. Manuscript: Dr. Buchman wrote the first draft and Drs. Nag, Lim, Shulman, VanderHorst, Schneider and Bennett reviewed and critiqued this and subsequent drafts of the manuscript.

Full Financial Disclosures of all Authors for the Past Year: The authors have reported no conflicts of interest.

ASB and SN are supported by grants from the NIH; JMS is supported by grants from the NIH/NIA (K08AG034290), the Parkinson’s Study Group and Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, and a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; ASPL: Canadian Institutes of Health Research Bisby Fellowship; American Academy of Neurology Clinical Research Training Fellowship; Dana Foundation Clinical Neuroscience; James S. McDonnell Foundation; VV: NIH, Judy Goldberg Foundation; Thomas Hartman Foundation; SEL: NIH/NIA; JAS: NIH and Advisory Board-Eli Lily; DAB: NIH, has received honoraria for non-industry sponsored lectures; has served as a paid consultant to Danone, Inc., Wilmar Schwabe GmbH & Co., Eli Lilly, Inc., Schlesinger Associates, and the Gerson Lehrman Group.

References

- 1.Louis ED, Bennett DA. Mild Parkinsonian signs: An overview of an emerging concept. Movement Disorders. 2007;22(12):1681–1688. doi: 10.1002/mds.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis ED, Tang MX, Schupf N. Mild parkinsonian signs are associated with increased risk of dementia in a prospective, population-based study of elders. Movement Disorders. 2010;25(2):172–178. doi: 10.1002/mds.22943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou G, Duan L, Sun F, Yan B, Ren S. Association between mild parkinsonian signs and mortality in an elderly male cohort in China. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2010;17(2):173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.07.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchman AS, Leurgans SE, Boyle PA, Schneider JA, Arnold SE, Bennett DA. Combinations of Motor Measures More Strongly Predict Adverse Health Outcomes in Old Age: The Rush Memory and Aging Project, a Community-Based Cohort Study. BMC Medicine. 2011;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greffard S, Verny M, Bonnet A-M, et al. Motor Score of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale as a Good Predictor of Lewy Body-Associated Neuronal Loss in the Substantia Nigra. Archives of Neurology. 2006;63(4):584–588. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickson DW, Braak H, Duda JE, et al. Neuropathological assessment of Parkinson’s disease: refining the diagnostic criteria. The Lancet Neurology. 2009;8(12):1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarow C, Lyness SA, Mortimer JA, Chui HC. Neuronal Loss Is Greater in the Locus Coeruleus Than Nucleus Basalis and Substantia Nigra in Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases. Arch Neurol. 2003 Mar 1;60(3):337–341. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braak H, Tredici KD, Rüb U, de Vos RAI, Jansen Steur ENH, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2003;24(2):197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchman AS, Shulman JM, Nag S, et al. Nigral pathology and parkinsonian signs in elders without Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(2):258–266. doi: 10.1002/ana.22588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Abbott RD, et al. Parkinsonian signs and substantia nigra neuron density in decendents elders without PD. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(4):532–539. doi: 10.1002/ana.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain Oct. 1991;114 ( Pt 5):2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and Findings From the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012 Apr 2; doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett DA, Shannon KM, Beckett LA, Wilson RS. Dimensionality of parkinsonian signs in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999 Apr;54(4):M191–196. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.4.m191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeArmond SJ, Fusco MM, Dewey MM. Structure of the human brain. A Photographic atlas. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Arnold SE, Wilson RS. The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(5):406–412. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SAS/STAT® Software for Unix, Version (9.18) [computer program] Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2002–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Census Bureau News Report. Dramatic Changes in US Aging. 2006 www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/aging_population/cv06-36.html.

- 18.Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickson D, Fujishiro H, DelleDonne A, et al. Evidence that incidental Lewy body disease is pre-symptomatic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2008;115(4):437–444-444. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DelleDonne A, Klos KJ, Fujishiro H, et al. Incidental Lewy Body Disease and Preclinical Parkinson Disease. Archives of Neurology. 2008;65(8):1074–1080. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frigerio R, Fujishiro H, Maraganore DM, et al. Comparison of Risk Factor Profiles in Incidental Lewy Body Disease and Parkinson Disease. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66(9):1114–1119. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rommelfanger KS, Weinshenker D. Norepinephrine: The redheaded stepchild of Parkinson’s disease. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2007;74(2):177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaias IU, Marzegan A, Pezzoli G, et al. A role for locus coeruleus in Parkinson tremor. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012 Jan 3;2012:5. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter ME, Yizhar O, Chikahisa S, et al. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(12):1526–1533. doi: 10.1038/nn.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruinstroop E, Cano G, Vanderhorst VGJM, et al. Spinal projections of the A5, A6 (locus coeruleus), and A7 noradrenergic cell groups in rats. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2012;520(9):1985–2001. doi: 10.1002/cne.23024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke RE, Dauer WT, Vonsattel JPG. A critical evaluation of the Braak staging scheme for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(5):485–491. doi: 10.1002/ana.21541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]