Abstract

Measurement of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid (3HIA) in human urine has been shown to be a useful indicator of biotin status for a variety of clinical situations, including pregnancy. The work described herein presents a novel UPLC-MS/MS method for accurate and precise quantitation of urinary 3HIA. This method utilizes sample preparation prior to quantitation that has been simplified compared to the previous GC-MS method. To demonstrate the suitability of the UPLC-MS/MS method for human bio-monitoring, this method was used to measure 3-HIA in 64 human urine samples from eight healthy adults in whom marginal biotin deficiency had been induced experimentally by egg white feeding. 3HIA was detected in all specimens; the mean concentration [±standard deviation (SD)] was 80.6±51 μM prior to inducing biotin deficiency. Mean excretion rate for 3HIA (expressed per mol urinary creatinine) before beginning the biotin-deficient diet was 8.5±3.2 mmol 3HIA per mol creatinine and the mean increased threefold with deficiency. These specimens had been previously analyzed by GC-MS; the two data sets showed strong linear relationship with a correlation coefficient of 0.97. These results provide evidence that this method is suitable for bio-monitoring of biotin status in larger populations.

Keywords: Ultra high-performance liquid chromatography, UPLC-MS/MS, 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid, Biotin status indicator, Marginal biotin deficiency

Introduction

Marginal biotin deficiency has been shown to be a teratogen in several species [1–5], and concern has been raised that biotin deficiency could cause cleft palate or limb shortening defects in the human fetus [6]. Accordingly, there is a need for accurate, practical indicators of marginal biotin status [7]. Currently, the best indicators of biotin status in humans include the following: (1) enzymatic activity of the biotin-dependent enzyme propionyl-CoA carboxylase in peripheral blood lymphocytes [8], (2) urinary excretion rate of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid (3HIA) measured by GC-MS [9, 10], (3) plasma concentration of 3-hydroxyisovaleryl-carnitine (3HIA-carnitine) measured by LC-MS/MS [11], and (4) urinary excretion rate of 3HIA-carnitine measured by LC-MS/MS [12]. The free organic acid 3HIA and the conjugated 3HIA-carnitine are products of leucine catabolism; they are produced in increased quantities because metabolism of methylcrotonyl CoA is diverted to an alternate pathway due to reduced activity of the biotin-dependent enzyme 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase [13–15].

In previous reports concerning urinary excretion of 3HIA as an indicator of biotin status, the urinary concentration of 3HIA was determined by GC-MS [9, 10]. GC-MS was also utilized to determine the effect of phenotypical factors such as antiepileptic therapy, smoking, and pregnancy on urinary excretion of 3HIA [6, 9, 16–20]. Unfortunately, measurement of urinary 3HIA by GC-MS requires a complex and time consuming sample preparation, which includes a multi-step, liquid–liquid extraction procedure followed by derivatization to form the di-trimethylsilyl (TMS)-3HIA derivative [21]. In addition, diTMS-3HIA rapidly decomposes in the presence of trace amounts of water, requiring that sample analyses be performed in a timely manner. These issues rendered the GC-MS method problematic for large-scale population studies and other applications that would be facilitated by high-throughput methods. To overcome these limitations, we have explored the use of LC-MS/MS to accurately quantify a modest increase above normal of specific biotin-related metabolites [11, 12, 22, 23] rather than the broader metabolomic approach used successfully by others [24]. We report herein the development of a simple, high-throughput UPLC-MS/MS method for the rapid quantitation of urinary 3HIA excretion. To demonstrate suitability of the UPLC-MS/MS method for routine bio-monitoring of 3HIA in human urine, 3HIA was measured in urine samples from human subjects experimentally rendered marginally biotin deficient.

Experimental

Reagents and chemicals

Methanol (LC-MS Optima™ grade) and water (Omisolve®) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Deionized (DI) water used for this work was purified to 18 MΩ-cm resistivity using a Direct Q UV3 water purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA). 3HIA (>98% pure) was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR). The authentic internal standard (IS) [2H8]-3-hydroxyisovaleric acid was synthesized in our laboratory according to a previously published method [21]. All other reagents including formic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical (St. Louis, MO).

Equipment

Compounds were separated using a Waters Acquity Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) system (Millipore). Sample analysis was performed using a Thermo Electron TSQ Quantum Ultra tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS) (San Jose, CA). A Precision Scientific (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) shaking water bath was used to warm urine samples to 60 °C. Precipitates were removed from urine samples by centrifugation using an IEC Centra CL3-R centrifuge (Thermo IEC, Needham Heights, MA).

Preparation of analytical standards, quality control standards, and subject samples

All human urine, including subject samples and pooled human urine for quality control (QC) purposes were thawed, warmed to 60 °C for 30 min, cooled to ambient temperature, and centrifuged at 3,000×g for 10 min to sediment urine precipitates as described previously [10]. The urine supernatant was either decanted by aspiration or sampled directly without disturbing the precipitate pellet. The human urine pool used to prepare QC standards was prepared by taking 40 mL aliquots from fresh untimed urine samples collected from six healthy adult volunteers (four female, two male). After pooling, the urine pool was thoroughly mixed, sub-aliquoted into 15 mL tubes, immediately frozen at −20 °C, and stored until needed.

Calibration standards were prepared from aqueous stocks of 3HIA and [2H8]-3HIA at concentrations of 125 μM. The analytical stock solutions were stored at −20 °C. From the 3HIA stock solutions, aqueous calibration standards with 3HIA concentrations of 5, 25, 50, 75, 100, and 125 μMwere prepared daily and interspersed among samples in each analytical batch. These concentrations span the range of 3HIA concentrations seen in biotin-sufficient and -deficient individuals after the fourfold dilution described below.

QC standards were prepared in the reference urine pool by adding a known quantity of 3HIA to produce final concentrations of 60, 250, or 400 μM. These concentrations were chosen to span the range of endogenous 3HIA concentrations measured in biotin-sufficient and biotin-deficient subjects. These urinary QC standards were sub-aliquoted into 100 μL volumes and stored at −70 °C.

Clinical study design

In order to compare 3HIA concentrations measured by the new UPLC-MS/MS method to the values previously published that were measured by the GC-MS method, 64 urine samples collected from eight participants (three women) obtained during experimental induction of asymptomatic marginal biotin deficiency were re-assayed by the new method. This research study was approved at the time and for the current analysis by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant as part of the consent process. Details for the experimental induction of biotin deficiency for this clinical study have been published previously [8, 25].

GC-MS analytical method

The GC-MS quantitative method utilized for the previously published sample analyses has been described previously [21]. Briefly, 3HIA and [2H8]-3HIA were both extracted from urine by a multi-step, liquid–liquid extraction procedure, TMS derivatives were synthesized using N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) and 1% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS); these diTMS-3HIA derivatives were quantitated by GC-MS against unlabeled 3HIA calibration standards using [2H8]-3HIA as the internal standard.

Quantitation by UPLC-MS/MS

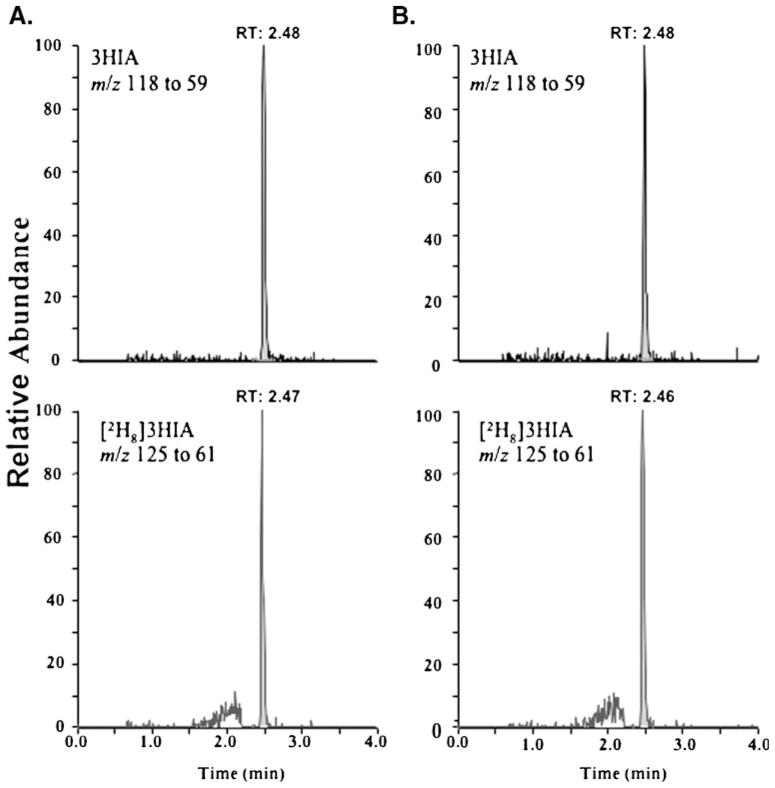

For quantitative analysis, subject urine samples and QC standards were diluted fourfold by mixing 25 μL of sample with 75 μL of DI water and vortexing for 10 s. All samples had IS added to yield a final concentration of 25 μM. Samples were cooled to 5 °C in the autosampler during analysis and 1 μL of each was injected onto a Waters Acquity UPLC system equipped with an HSS T3 (2.1×100 mm, 1.8 μm) column (Millipore) maintained at 55 °C. The mobile phases were 0.01% formic acid and methanol. The initial mobile phase composition was 0% methanol at the time of injection and was held constant for 1 min. The percentage of methanol in the mobile phase composition was increased linearly to 100% over 2 min, and then decreased to 0% over 0.2 min. The column was allowed to re-equilibrate for 0.8 min to complete the LC cycle. The flow rate was held constant at 400 μL/min throughout the LC cycle. The switching valve on the TSQ Quantum MS was used to divert the first 200 μL (equivalent to 30 s) of effluent flow containing un-retained compounds to waste. The retention time for both 3HIA and IS ranged between 2.44 and 2.48 min for all samples analyzed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Representative chromatograms for: A a prepared 60 μM urine QC sample, B a representative human subject urine sample

The electrospray voltage and source temperature were optimized at −4,000 V (negative mode electrospray ionization) and 350 °C, respectively. 3HIA and [2H8]-3HIA were acquired in selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode monitoring the ion transitions of m/z 117.0 to 59.1 and m/z 125.0 to 61.0, respectively. The collision energy was optimized for both compounds at 20 V. Xcalibur software (Version 2.0, San Jose, CA) was used to control the overall operation of the UPLC system and the mass spectrometer.

Results and Discussion

A novel UPLC-MS/MS method is reported that is suitable for routine measurement of the urinary concentration of 3HIA. In contrast to the previously utilized GC-MS method, extraction and derivatization steps are not required. To characterize the quantitative performance of the method, the linear range, limit of quantitation, reproducibility, and repeatability of interday and intraday precision and accuracy were determined. To evaluate the relationship of results of this new method to results of previous studies utilizing 3HIA as an indicator of marginal biotin deficiency, the UPLC-MS/MS method was used to determine the concentration of 3HIA in 64 urine samples from subjects who had been rendered progressively biotin deficient.

Before samples analysis, the linearity, limit of detection, and limit of quantitation were determined on three nonsequential days; freshly prepared calibration standards were quantitated individually (n=6 calibration standards per curve). Calibration curves for each analytical batch were constructed by plotting the peak area ratio of analyte to IS against the ratio of the concentration of 3HIA to the concentration of IS. An unweighted linear regression was performed on the data from each of the three calibration curves. The mean slope (±SD) was 1.47±0.16, and the mean y-intercept was −0.0084±0.143. The mean correlation coefficient was 0.97 with a range of 0.96–1.00. The limit of quantitation (LOQ) was determined to be 6.5 pmol 3HIA on column (injection volume of 1 μL) with signal to noise >10, corresponding to an LOQ in undiluted urine of 26 μM.

Assessment of method accuracy and precision

The precision and accuracy of the method across the calibration range was assessed by replicate measurements of reference urine QC standards at three levels (Table 1). The three QC levels were chosen based on biologically relevant 3HIA concentrations. A representative urine pool was constructed from urine samples from six healthy adults as described above in “Preparation of analytical standards, quality control standards, and subject samples.” The mean urinary 3HIA concentration in the pool was 39.1±6.8 μM (mean±1 SD) based on nine replicate measurements. Various amount of unlabeled 3HIA were added to aliquots of the pooled urine to generate the final QC concentrations of 60, 250, and 400 μM 3HIA. Intraday precision and accuracy for each QC standard were calculated as % relative standard deviation (%RSD) and % relative error (%RE), respectively and are presented in Table 1. The interday precision and accuracy (Table 2) demonstrate the suitability of the UPLC-MS/MS method for quantitation of 3HIA across the physiological range of urinary 3HIA concentrations observed in healthy humans.

Table 1.

Intraday precision and accuracy for diluted QC standards

| Batch | QC 60 μM | QC 250 μM | QC 400 μM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision (%RSD) | Precision (%RSD) | Accuracy (%RE) | Precision (%RSD) | Accuracy (%RE) | Accuracy (%RE) | |

| 1 | 13.7 | 8.5 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 6.7 |

| 2 | 12.8 | 6.1 | 7.7 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 16.0 |

| 3 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 14.4 |

Calculated as the % relative standard deviation (RSD) for the QC standards measured in triplicate for each concentration in each independent batch after correction for endogenous content of 3HIA in the urine. Expressed as % relative error (%RE) and calculated as [(corrected mean calculated concentration)−(nominal concentration/nominal concentration)]×100. Dilution factor=4

Table 2.

Interday mean concentration, precision, and accuracy for prepared and diluted QC standards

| Nominal concentration (μM) | Mean calculated concentration (μM) | Precision (%CV) | Accuracy (%RE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60 (n=9) | 67.4 | 10.2 | 12.3 |

| 250 (n=9) | 256 | 7.02 | 2.43 |

| 400 (n=9) | 409 | 3.42 | 2.36 |

Calculated from the linear least-squares regression composed for the calibration standards (n=6) for the three separate analytical batches. Calculated as the coefficient of variation (%CV) for the QC standard (n=9) concentrations after correction for endogenous content of 3HIA in urine. Expressed as % relative error (%RE) and calculated as [(corrected mean calculated concentration−nominal concentration)/nominal concentration]×100. Dilution factor=4

Application of the UPLC-MS/MS method to human samples

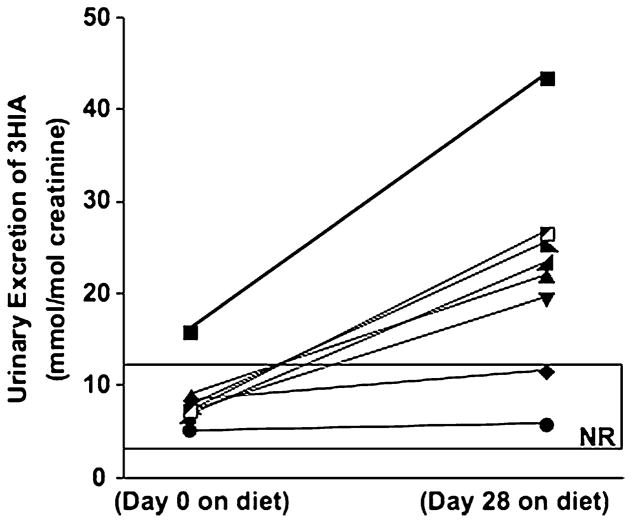

To demonstrate the suitability of the UPLC-MS/MS method for human bio-monitoring, the method was used to measure 3HIA in 64 human samples. These samples were obtained from eight normal healthy adults in whom marginal biotin deficiency had been induced experimentally by egg white feeding [8]. 3HIA was detected in all specimens; the mean concentration (±SD) was 80.6±51 μM before beginning the biotin-deficient diet. Mean excretion rate for 3HIA (expressed per mole urinary creatinine) before beginning the biotin-deficient diet was 8.5±3.2 mmol 3HIA per mole creatinine, and the mean excretion rate increased about 3 fold (p<0.02 by Wilcoxon Sign Rank test) after 28 days on the biotin-deficient diet (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Excretion of 3HIA in human urine before (Day 0) and after (Day 28) induction of marginal biotin deficiency by egg white feeding. NR denotes normal range

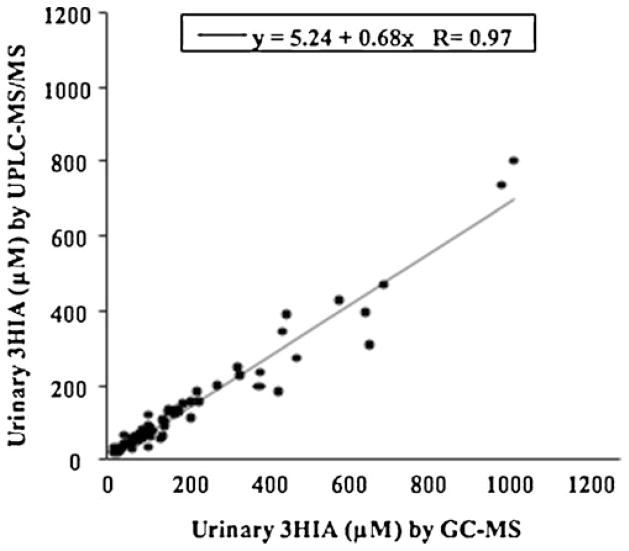

Individual measurements obtained with the novel UPLC-MS/MS method correlated strongly with previous GC-MS measurements (Fig. 3); the correlation coefficient was 0.97, and the coefficient of determination R2 was 0.95. These data provide evidence that the assays are complementary. However, the slope of the regression line was 0.68 suggesting that the two analyses differed by approximately 30%. The source of this difference is unknown. This discrepancy might have arisen from the different unlabeled 3HIA standards used for instrument calibrations. The 3HIA standards for the GC-MS measurements were prepared in our laboratory because at that time no commercial source was available; we reported purity of the 3HIA and [2H8]-3HIA were approximately >95% on the basis of elemental analyses, proton NMR, GC, and GC-MS [21], but no gravimetric analysis was performed. The novel UPLC-MS/MS method was calibrated against authentic commercial 3HIA standards. Moreover, the samples we analyzed by the UPLC-MS/MS method had been stored frozen at −70 °C for more than a decade. These observations emphasize the established importance of contemporaneous control(s) that are appropriate for the scientific question (e.g., biotin sufficient vs. biotin deficient).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of urinary 3HIA concentrations (μM) measured using the UPLC-MS/MS method against the GC-MS method

Assessment of urine matrix effects

In order to assess effects of the urine matrix at the standard fourfold dilution used for all determinations by this ULC-MS/MS method, we measured the average ratio of the absolute peak area for the [2H8]-3HIA internal standard in reference QC standard and individual human urine samples relative to the absolute peak area for the [2H8]-3HIA internal standard in contemporaneously measured calibration standards prepared in water. In the 27 QC samples prepared in pooled urine, the average ratio was 89%. In the 64 study subject samples, the average ratio was 94%. These observations suggest that urine matrix had minimal effects on detection of 3HIA at the dilution used for the urine samples.

Conclusions

The UPLC-MS/MS approach described in this report provides a precise and accurate method for measuring the concentration of 3HIA in urine specimens. This UPLC-MS/MS method has distinct technical advantages over the GC-MS method including simplified sample preparation and increased sample stability compared to the diTMS-3HIA derivatives that will likely lead to increased productivity, reduced analysis costs, and a reduction in sample preparation errors. This study provides evidence that this method is suitable for human bio-monitoring and provides increased capacity to assess biotin status in larger populations exposed to varying phenotypical factors that have the potential to alter biotin status.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following agencies: National Institutes of Health, grants R37 DK36823 (DMM), R37 DK36823-26S1 (DMM), and R01 DK79890-01S1 (DMM); Arkansas Biosciences Institute, Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Proceeds Act of 2000 (DMM and GB). The project described was supported by Award Number 1UL1RR029884 from the National Center for Research Resources. We thank Katie Estes and Anna Bogusiewicz, Ph.D., at UAMS for their technical assistance, and Marie Tippett at UAMS for editorial support.

Contributor Information

Thomas D. Horvath, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W. Markham Street, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA

Nell I. Matthews, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W. Markham Street, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA

Shawna L. Stratton, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W. Markham Street, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA

Donald M. Mock, Email: mockdonaldm@uams.edu, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W. Markham Street, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA. Department of Pediatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W. Markham Street, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA

Gunnar Boysen, Email: gboysen@uams.edu, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W. Markham Street, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA.

References

- 1.Zempleni J, Mock D. Marginal biotin deficiency is teratogenic. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;223(1):14–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe T, Endo A. Teratogenic effects of maternal biotin deficiency in mouse embryos examined at midgestation. Teratol. 1990;42:295–300. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420420313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe T, Endo A. Biotin deficiency per se is teratogenic in mice. J Nutr. 1991;121:101–104. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mock DM, Mock NI, Stewart CW, LaBorde JB, Hansen DK. Marginal biotin deficiency is teratogenic in ICR mice. J Nutr. 2003;133:2519–2525. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.8.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe T, Dakshinamurti K, Persaud TVN. Biotin influences palatal development of mouse embryos in organ culture. J Nutr. 1995;125:2114–2121. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.8.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mock D. Marginal biotin deficiency is common in normal human pregnancy and is highly teratogenic in the mouse. J Nutr. 2009;139(1):154–157. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.095273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Said HM. Biotin: the forgotten vitamin. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75 (2):179–180. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratton SL, Bogusiewicz A, Mock MM, Mock NI, Wells AM, Mock DM. Lymphocyte propionyl-CoA carboxylase and its activation by biotin are sensitive indicators of marginal biotin deficiency in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):384–388. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mock NI, Malik MI, Stumbo PJ, Bishop WP, Mock DM. Increased urinary excretion of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid and decreased urinary excretion of biotin are sensitive early indicators of decreased status in experimental biotin deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:951–958. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mock DM, Henrich CL, Carnell N, Mock NI. Indicators of marginal biotin deficiency and repletion in humans: validation of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid excretion and a leucine challenge. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1061–1068. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stratton SL, Horvath TD, Bogusiewicz A, Matthews NI, Henrich CL, Spencer HJ, Moran JH, Mock DM. Plasma concentration of 3-hydroxyisovaleryl carnitine is an early and sensitive indicator of marginal biotin deficiency in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(6):1399–1405. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stratton SL, Horvath TD, Bogusiewicz A, Matthews NI, Henrich CL, Spencer HJ, Moran JH, Mock DM. Urinary excretion of 3-hydroxyisovaleryl carnitine is an early and sensitive indicator of marginal biotin deficiency in humans. J Nutr. 2011;141(3):353–358. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.135772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweetman L, Williams JC. Branched chain organic acidurias. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. 7. Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1995. pp. 1387–1422. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roschinger W, Millington DS, Gage DA, Huang ZH, Iwamoto T, Yano S, Packman S, Johnston K, Berry SA, Sweetman L. 3-Hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine in patients with deficiency of 3-methylcrotonyl CoA carboxylase. Clin Chim Acta. 1995;240(1):35–51. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(95)06126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maeda Y, Ito T, Ohmi H, Yokoi K, Nakajima Y, Ueta A, Kurono Y, Togari H, Sugiyama N. Determination of 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine and other acylcarnitine levels using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in serum and urine of a patient with multiple carboxylase deficiency. J Chromatogr B. 2008;870(2):154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sealey WM, Teague AM, Stratton SL, Mock DM. Smoking accelerates biotin catabolism in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:932–935. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.4.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mock DM, Quirk JG, Mock NI. Marginal biotin deficiency during normal pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(2):295–299. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mock DM. Marginal biotin deficiency is teratogenic in mice and perhaps humans: a review of biotin deficiency during human pregnancy and effects of biotin deficiency on gene expression and enzyme activities in mouse dam and fetus. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16:435–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mock DM, Dyken ME. Biotin catabolism is accelerated in adults receiving long-term therapy with anticonvulsants. Neurology. 1997;49(5):1444–1447. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.5.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mock DM, Mock NI, Lombard KA, Nelson RP. Disturbances in biotin metabolism in children undergoing long-term anticonvulsant therapy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26(3):245–250. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199803000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mock DM, Jackson H, Lankford GL, Mock NI, Weintraub ST. Quantitation of urinary 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid using deuterated 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid as internal standard. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1989;18:652–656. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200180903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horvath TD, Stratton SL, Bogusiewicz A, Pack L, Moran J, Mock DM. Quantitative measurement of plasma 3-hydroxyisovaleryl carnitine by LC-MS/MS as a novel bio-marker of biotin status in humans. Anal Chem. 2010;82(10):4140–4144. doi: 10.1021/ac1003213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horvath TD, Stratton SL, Bogusiewicz A, Owen SO, Mock DM, Moran JH. Quantitative measurement of urinary excretion of 3-hydroxyisovaleryl carnitine by LC-MS/MS as an indicator of biotin status in humans. Anal Chem. 2010;82 (22):9543–9548. doi: 10.1021/ac102330k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preinerstorfer B, Schiesel S, Lämmerhofer M, Lindner W. Metabolic profiling of intracellular metabolites in fermentation broths from beta-lactam antibiotics production by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methods. J Chromatography A. 2010;1217(3):312–328. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vlasova TI, Stratton SL, Wells AM, Mock NI, Mock DM. Biotin deficiency reduces expression of SLC19A3, a potential biotin transporter, in leukocytes from human blood. J Nutr. 2005;135 (1):42–47. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]