There is overwhelming evidence that oxidative stress and oxidative damage play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (1–3). The sources of the increased oxidative stress in the respiratory compartment of COPD patients derive from the increased burden of oxidants from environmental exposures, such as cigarette smoke (CS) and air pollutants, and from the increased amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) released from leukocytes and macrophages involved in the inflammatory process in the lungs of COPD subjects (1–5). These ROS and RNS are capable of causing oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, carbohydrates and proteins, and thereby mediate an array of downstream processes that contribute to the development and progression of COPD. They also activate resident cells in the lung, particularly epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages, to generate chemotactic molecules that recruit additional inflammatory cells (neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes) into the lung (5–7), which in turn perpetuates oxidative stress in the lung. Collectively, these events lead to a vicious cycle of persistent inflammation, accompanied by chronic oxidative stress, which lead to disturbances in the protease-antiprotease balance, defects in tissue repair mechanisms, accelerated apoptosis and enhanced autophagy in lung cells, which have all been linked to the severity and progression of COPD (8–11).

CS is, by far, the most important source of environmentally derived ROS in COPD (12). CS contains more than 4000 different chemicals and generates more than 1015 oxidants per puff, directly or indirectly, through various processes such as the Haber-Weiss reaction (13). ROS, in turn, can induce lipid peroxidation and yield products such as malondialdehyde (MDA), which have the ability to stimulate pulmonary inflammation (5). COPD patients have increased MDA levels in the peripheral circulation, which increase further with progression of disease (14,15). Furthermore, the levels of lipid peroxidation products are also increased in the breath condensate and plasma of smokers and patients with stable COPD, with concentrations correlating inversely with lung function. ROS/RNS can initiate and propagate inflammatory responses by upregulating redox-sensitive transcription factors and activating their downstream signalling pathways (1,5) predominantly in epithelial cells and inflammatory cells (macrophages and neutrophils) in the lung. They also target signalling molecules, such as small G proteins and numerous proinflammatory transcription factors (eg, NF-κB) (7), to induce and sustain a proinflammatory state that enhances the production of cell-derived ROS. The principal ROS-generating enzyme system in inflammatory cells is NADPH oxidase; however, other enzyme systems are also activated, such as the xanthine/xanthine and the heme peroxidases system, which have all been shown to be upregulated in COPD patients (1,16). Similarly, RNS in the form of nitric oxide production is generated by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which in the presence of superoxide anion forms a powerful and damaging ROS, peroxynitrite anion (17). Upregulation of the iNOS system (and its downstream oxidative pathways) is believed to be one of the earliest (and pivotal) molecular events that trigger emphysema and pulmonary hypertension related to cigarette smoking (18). In addition, CS also compromises the antioxidant defenses of the lung by irreversibly modifying glutathione (GSH) and various redox-sensitive signalling proteins and transcription factors, such as the nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor expressed predominantly in epithelium and alveolar macrophages, which has an essential protective role in the lungs through the activation of an antioxidant response element that regulates antioxidant and cytoprotective genes (19,20). COPD patients may also exhibit decreased expression of heme oxygenase 1 and catalase, components of the Nrf2 response pathway, and decreases in catalase and cytochrome C oxidase subunits, components of the mitochondrial antioxidant pathway (19–21). This imbalance between oxidative stress and antioxidant defenses in the lung are believed to be a key step in the pathogenesis of the development and progression of COPD.

In the current issue of the Canadian Respiratory Journal, Zeng et al (22) (pages 35–41) showed that COPD patients have increased expression of MDA in induced sputum, which increases further during acute exacerbation, suggesting increased oxidative stress in the airways. Zeng et al also showed that the antioxidative markers (GSH and superoxide dismutase) in induced sputum were significantly down-regulated, resulting in an imbalance between oxidative stressors and antioxidants in the airways, especially during acute exacerbations. Although not evaluated in the study by Zeng et al, these perturbations in the oxidative balance could perpetuate (or amplify) the inflammatory responses in the lung and possibly contribute to disease progression and poor health outcomes during acute exacerbations.

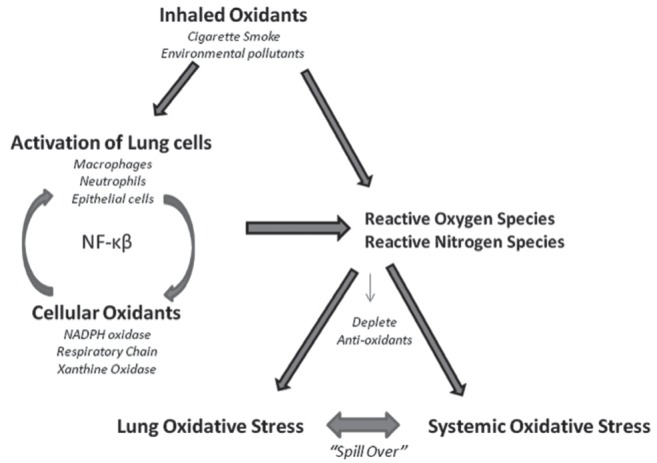

More interestingly, Zeng et al also measured the same pro- and antioxidants in the plasma of their study subjects, showing a surprising similar imbalance of oxidative stress versus antioxidant capacity in the systemic circulation. COPD is now widely recognized as not simply an inflammatory lung disease, but also a chronic systemic disease (23) with diverse extrapulmonary manifestations, especially in the cardiovascular system (24). Translocation of proinflammatory mediators from the lung into the circulation has been proposed as a potential mechanism of how COPD impacts cardiovascular disease (23,24). Consistent with this theory, recent animal studies have shown translocation of interleukin (IL)-6 from the lung into the bloodstream after endotoxin- or air pollution-induced lung inflammation (25,26). IL-6 translocation has been associated with vascular dysfunction and thrombosis (25–27), suggesting that lung inflammation is one of the driving forces of vascular disease. Systemic oxidative stress has also been shown to play a vital role the pathogenesis of vascular disease, such as atherosclerosis, and in triggering acute coronary events (28). Although translocation of oxidants and/or antioxidants from the lung into the circulation has not been previously documented, the close relationship of the oxidant/antioxidant balance in the lung with that in the systemic circulation, as reported by Zeng et al, suggests that these oxidative molecules generated in the lung may ‘spill over’ into the circulation (Figure 1). However, this hypothesis needs to be directly tested to determine whether oxidative stress from lung sources significantly contributes to the downstream cardiovascular disease associated with COPD. This mechanism could be even more relevant during an acute exacerbation of COPD in which the burden of oxidative stress in the lung is increased exponentially. There is good epidemiological evidence that acute lung infections trigger acute vascular events such as acute coronary syndrome (29,30) but the precise molecular pathways by which this occurs are largely unknown. Previous research has implicated lung inflammation driven by alveolar macrophages and molecules such as IL-6 (25,26); however, there may be other more salient molecules and pathways, such as downstream effects of oxidative stress, involved in this process.

Figure 1).

Oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in subjects exposed to inhaled oxidants such as cigarette smoke and environmental pollutants. Both oxidants generated from inhaled oxidants and by inflammatory cells in the lung contribute to a burden of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). The ROS and RNS deplete the normal antioxidant defenses (such as glutathione) of the lung, and activate redox-sensitive transcription factors that act as signalling molecules to perpetuate the inflammatory response in the lung. Collectively, this produces a pro-oxidative/proinflammatory state in the lung that promote the translocation or ‘spill over’ of oxidants and proinflammatory mediators into the circulation

The findings of Zeng et al have therapeutic implications. Oxidative stress inhibits the expression of glucocorticoid receptors, which are required for corticosteroid binding and translocation to target genes. Thus, in a pro-oxidant milieu, corticosteroids are relatively ineffective, which may explain the poor therapeutic performance of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD. Because an oxidant/antioxidant imbalance is implicated in the pathogenesis of COPD, therapeutic intervention to correct the imbalance could be effective in the treatment of COPD and may boost the therapeutic potential of corticosteroids, specifically during acute exacerbation. Therefore, targeting oxidative stress with antioxidants or boosting the endogenous levels of antioxidants is likely to have a beneficial outcome in the treatment of COPD. Antioxidants, such as glutathione, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, Nrf2 activators and dietary polyphenols (resveratrol, and green tea catechins/quercetin), have all been reported to increase intracellular thiol status and GSH biosynthesis, leading to detoxification of free radicals and oxidants, with attenuation of the resulting inflammatory responses in the lung (31). Because a variety of oxidants, free radicals and aldehydes are implicated in the pathogenesis of COPD, it is reasonable that therapeutic administration of multiple antioxidants will be needed to effectively correct the oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in the lung and dampen the inflammatory response associated with COPD, particularly during acute exacerbations of COPD. This therapeutic intervention may also correct the systemic oxidant/antioxidant imbalance and the downstream systemic comorbidities caused by COPD and during acute COPD exacerbation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rahman I, MacNee W. Role of oxidants/antioxidants in smoking-induced lung diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21:669–81. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson D, Macnee W. Targeted treatment in COPD: A multi-system approach for a multi-system disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:321–35. doi: 10.2147/copd.s2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman I, MacNee W. Lung glutathione and oxidative stress: Implications in cigarette smoke-induced airway disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L1067–088. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.6.L1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida T, Tuder RM. Pathobiology of cigarette smoke induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1047–82. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–42. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishida M, Maruyama Y, Tanaka R, Kontani K, Nagao T, Kurose H. G[alpha]i and G[alpha]o are target proteins of reactive oxygen species. Nature. 2000;408:492–5. doi: 10.1038/35044120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poli G, Leonarduzzi G, Biasi F, Chiarpotto E. Oxidative stress and cell signalling. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:1163–82. doi: 10.2174/0929867043365323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Senescence hypothesis for the pathogenetic mechanism of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:596–601. doi: 10.1513/pats.200904-017RM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Alveolar cell senescence in patients with pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:886–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1374OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Churg A, Wright JL. Proteases and emphysema. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:153–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000149592.51761.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavarra E, Lucattelli M, Gambelli F, et al. Human SLPI inactivation after cigarette smoke exposure in a new in vivo model of pulmonary oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L412–L417. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snider GL. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: risk factors, pathophysiology and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 1989;40:411–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.40.020189.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Church DF, Pryor WA. Free radical chemistry of cigarette smoke and its toxicological implications. Environ Health Perspect. 1985;64:111–26. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8564111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kluchova Z, Petrasova D, Joppa P, Dorkova Z, Tkacova R. The association between oxidative stress and obstructive lung impairment in patients with COPD. Physiol Res. 2007;56:51–6. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montano M, Cisneros J, Ramirez-Venegas A, et al. Malondialdehyde and superoxide dismutase correlate with FEV(1) in patients with COPD associated with wood smoke exposure and tobacco smoking. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:868–74. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.491840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinamonti S, Leis M, Barbieri A, et al. Detection of xanthine oxidase activity products by EPR and HPLC in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:771–9. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen-Heininger YM, Persinger RL, Korn SH, et al. Reactive nitrogen species and cell signaling: Implications for death or survival of lung epithelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:9S–16S. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2206008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanzetti M, da Costa CA, Nesi RT, et al. Oxidative stress and nitrosative stress are involved in different stages of proteolytic pulmonary emphysema. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1993–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boutten A, Goven D, Boczkowski J, Bonay M. Oxidative stress targets in pulmonary emphysema: Focus on the NRF2 pathway. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:329–46. doi: 10.1517/14728221003629750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kensler TW, et al. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-NRF2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malhotra D, Thimmulappa R, Navas-Acien A, et al. Decline in NRF2-regulated antioxidants in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease lungs due to loss of its positive regulator, DJ-1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:592–604. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-380OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Zeng M, Li Y, Jiang Y, Lu G, Huang X, Guan K. Local and systemic oxidative stress and glucocorticoid receptor in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Can Resp J. 2012:35–41. doi: 10.1155/2013/985382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Eeden SF, Sin DD. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A chronic systemic inflammatory disease. Respiration. 2008;75:224–38. doi: 10.1159/000111820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Eeden SF, Leipsic J, Man SF, Sin DD. The relationship between lung inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2012;186:11–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0455PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamagawa E, Suda K, Yuan W, et al. Endotoxin-induced translocation of interleukin-6 from lungs to the systemic circulation. Innate Immun. 2009;15:251–8. doi: 10.1177/1753425909104782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kido T, Tamagawa E, Bai N, et al. Particulate matter induces translocation of IL-6 from the lung to the systemic circulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:197–204. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0427OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suda K, Tsuruta M, Eom J, et al. Acute lung injury induces cardiovascular dysfunction: Effects of IL-6 and budesonide/formoterol. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:510–6. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0169OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buffon A, Biasucci LM, Liuzzo G, D’Onofrio G, Crea F, Maseri A. Widespread coronary inflammation in unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:5–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Farrington P, Vallance P. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2611–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corrales-Medina VF, Musher DM, Wells GA, Chirinos JA, Chen L, Fine MJ. Cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: Incidence, timing, risk factors, and association with short term mortality. Circulation. 2012;125:773–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman I. Antioxidant therapeutic advances in COPD. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2008;2:351. doi: 10.1177/1753465808098224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]