Abstract

This qualitative study examined the experiences of HIV-positive African-American and African Caribbean childbearing women related to decisions about HIV testing, status disclosure, adhering to treatment, decisions about childbearing, and experiences in violent intimate relationships. Twenty-three women completed a 60-minute in-depth interview. Six themes emerged: perceived vulnerability to HIV infection; feelings about getting tested for HIV; knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors after HIV diagnosis; disclosure of HIV status; living with HIV (positivity, strength, and prayer); and, experiences with physical and sexual violence. Three women (13%) reported perinatal abuse and 10 women (n = 23, 43.4%) reported lifetime abuse. Positive experiences and resilience were gained from faith and prayer. Most important to the women were the perceived benefits of protecting the health of their baby. Findings suggest that policies supporting early identification of HIV-positive childbearing women are critical in order to provide counseling and education in forming their decisions for safety precautions in violent intimate partner relationships.

Keywords: African-American, African Caribbean, childbearing, HIV/AIDS, intimate partner violence, women

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and interpersonal violence are global health issues disproportionately affecting childbearing women of African heritage. As a result, these women have the highest HIV/AIDS burden (Archibald, 2010; Brewer, Zhao, Metsch, Coltes, & Zenilman, 2007; CDC, 2010; Krishnan et al., 2008). Women of African heritage are more vulnerable because of inequities, inequalities, and partners who are involved in risky behaviors (Aral, Adimora, & Fenton, 2008; Adimora et al., 2006; Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010; Tillerson, 2008). Researchers have found that social inequities and inequalities such as poverty, social norms, and expectations make women vulnerable and at risk for violence (Tillerson, 2008).

Background and Significance

Intimate Partner Violence

Interpersonal violence is the use of physical force or power, either threatened or actual, against another person that results in, or has a high likelihood of resulting in, injury, death, psychological harm, or deprivation (World Health Organization [WHO], 2002). Interpersonal violence against women, particularly intimate partner violence, has been linked to increased vulnerability to HIV, underscoring global and public health implications in HIV prevention efforts (Campbell et al., 2002; Dunkle et al., 2006; Gielen, Gandour, Burke, Mahoney, McDonnell, & O’Campo, 2007). In addition, intimate partner violence propagates HIV transmission (Sareen, Pagura, & Grant, 2009; Silverman, Decker, Saggurti, Balaiah, & Raj, 2008). It has been linked to power imbalances associated with women’s inability to negotiate safe sex, maintain strong financial support, and realize economic stability. Economic challenges such as poverty force women to engage in sexual relations with older men and multiple partners (Aral, Adimora, & Fenton, 2008; Lichtenstein, 2008), limiting their choices to negotiate safe sex with subsequent exposure to HIV infection (Roundtree & Mulrany, 2010).

Exposure to HIV

Being exposed to HIV, and getting infected, place childbearing women in critical positions that require them to make important life changing decisions. These decisions include HIV testing, HIV status disclosure, adhering to treatment regimens, and decisions about continuing the pregnancy and parenting their child. Decisions may involve multiple interrelated factors, including individual beliefs, relationship status, and social and economic factors (Roundtree & Mulrany, 2010). Decisions about their pregnancy may be influenced by fear of disclosing their HIV status to intimate partners, family and/or friends (Peltzer, Chao, & Dana, 2008); and they fear that their experiences involving violence might increase, thus creating major barriers to accessing care services. A study involving HIV-positive Black women in four U.S. cities found that even though some women made the decision to have children, they expressed concern that if they got sick they would be unable to care for them and no one would take care of their children when they died (Kirshenbaum et al., 2004). Contrasting results related to childbearing women’s decisions were found in the literature (Craft, Delaney, Bautista, & Serovich, 2007; Gruskin, Ahmed, & Ferguson, 2008). Specifically, there were differences in results related to HIV-positive women’s decisions whether to continue with the pregnancy or to terminate it for reasons such as a strong desire to have children versus concerns for the child’s health and inability to care for the child when they were too ill. Kanniappan, Jeyapaul, and Kalyanwala (2008) found that women desired to keep the pregnancy, depending on available social support. Craft et al., (2007) found that almost 75% of HIV-positive women did not desire pregnancy. Limited research has explored HIV-positive childbearing women’s feelings and abuse experiences (Peltzer, Chao, & Dana, 2008).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to describe and explore African-American and African Caribbean women’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, feelings, interpersonal experiences related to participating in voluntary counseling and testing (VCT), disclosing their HIV status, and their decisions related to pregnancy care and parenting practices.

The following questions were explored: (a) What are the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and abuse experiences of HIV-positive women? (b) What influenced HIV-positive women’s decisions related to their participation in VCT, disclosure of HIV status, and continuing their pregnancy and parenting practices?

Methodology

Conceptual Model

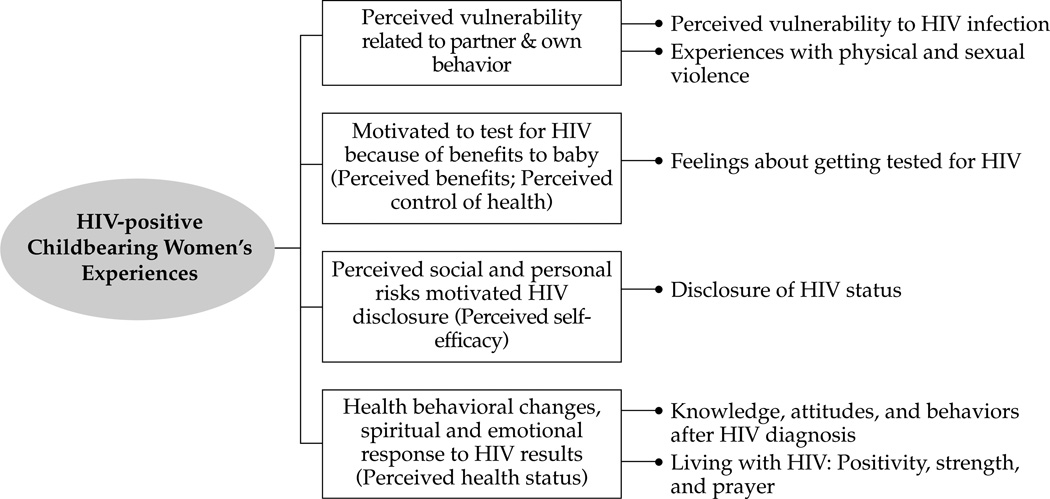

The Health Belief Model (HBM) (Pender, Murdaugh, & Parsons, 2006) provided the conceptual background for this study. The theory posits that decisions and behavioral outcomes are influenced by a confluence of interrelated concepts of cognitive perceptual factors of perceived control of health; perceived health status; perceived self-efficacy; and perceived benefits. Also important in the HBM are the modifying factors related to demographic, biological, and individual characteristics; interpersonal influences, and behavioral factors. Perceived risks and benefits could block or facilitate progression to positive outcomes or favorable decisions. Figure 1 illustrates the inter-relationships among the study themes and constructs of the HBM (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Model illustrating the inter-relationships among study themes and constructs of the Health Belief Model

Research Design, Setting and Sample

Setting

In Baltimore, there were 9,447 new cases of HIV; 667 were African-Americans and 348 were females. Total AIDS cases were 7,085 that included 421 African-Americans and 191 females. Baltimore women have a 37.6% prevalence rate (Baltimore City, 2009; CDC, 2009). AIDS cases were at 37.7 cases/100,000 population. HIV prevalence among African-Americans declined up to 10% in the previous 10 years, yet, African-Americans are eight times more likely to die from HIV and related diseases. Cumulative data for females in Baltimore diagnosed with HIV were 3,662, and with AIDS, 2,512 (Baltimore City, 2009).

United States Virgin Islands (USVI) has the second highest per capita rate for AIDS and the third highest per capita rate for HIV in the United States and five territories (CDC, 2009). At the end of 2010, the estimated numbers of persons living with HIV was 252; AIDS was 281 (Virgin Islands Department of Health [VIDOH], 2010). Six females were reported as HIV-infected and 5 women were reported with AIDS during 2010 (VIDOH, 2010). In communication with the Director of HOPE, INC., the cumulative numbers of females diagnosed with HIV since data was collected is 135 women; and 209 women have been diagnosed with AIDS (March 16, 2010).

Study Design and Sample

This in-depth qualitative design study was a component of a larger mixed methods study. The quantitative study included demographic data and the use of questionnaires to obtain information on attitudes, knowledge, beliefs, decisions related to testing and disclosure, health and parenting practices; as well as questionnaires related to depression, and self-esteem. A total of 67 women were recruited and consent was obtained for the parent study. Inclusion criteria were: African-American and African Caribbean women clinically diagnosed as HIV-positive; pregnant or having infants 12 months or younger; receiving pre-natal care; self-reported interpersonal violence currently, or within 12 months prior to the pregnancy; residing in Baltimore and the USVI. Exclusion criteria were: not meeting any of the above criteria or medically diagnosed with mental or psychiatric illness. Data and findings presented here are from the 23 women (N = 23) who agreed to participate in the qualitative study.

Institutional Review Board Approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Johns Hopkins University and the USVI before participant recruitment and data collection began. A total of 67 women included in this study had given consent for the larger study. The 23 women described in the qualitative study reported here volunteered to complete the in-depth interviews and signed an additional consent form.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Flyers were posted at data collection sites. Approximately 60-minute in-depth interviews were conducted using a structured interview guide. Interviewers used probe questions to direct the focus of the interviews. Questions included demographic information such as age, years of formal education, pregnancy health history, decisions about HIV testing, learning about their diagnosis, pregnancy and parenting practices, disclosure of HIV status, behaviors and changes in intimate relationships related to HIV test results, and partner relationships. Women were interviewed until no new information was generated, suggesting that data saturation was reached.

Instrumentation

The in-depth interview guide was designed by the research team to obtain data about the women’s beliefs, feelings, and attitudes that may be influenced by their HIV/AIDS status and related stigma experiences. The research team formulated the content for the questions based upon previous studies examined, as well as gaps in what has been studied. The open-ended questions for the interview were designed to allow the women to tell their “story” using “their own words.” Questions included: testing status; how the decision was made about testing; attitudes, beliefs, and feelings after they learned of their HIV status; disclosure of their HIV status to whom and when; after disclosure, changes in their relationships with partners (i.e., conflict, physical, sexual and/or mental violence/abuse); family, friends (i.e., cutoff/isolation, conflict, physical, sexual and/or mental violence/abuse); since learning their status had they changed anything they did or said in relation to their HIV status; after becoming aware of their status had it changed their beliefs, feelings and attitudes related to parenting; other questions were also asked about sources and types of social support. The in-depth interviews lasted approximately 45–60 minutes.

Ensuring Scientific Rigor and Trustworthiness

For credibility and confirmability, the interview guide reflected questions that generated information related to childbearing women’s HIV and interpersonal experiences. The guide was reviewed by a nurse scholar whose area of expertise is women, maternal and child health. Second, the four investigators independently conducted manual analysis, constantly comparing the raw data to transcribed interviews in an iterative process to be certain both were comparable. Using multiple analysts (triangulation) for qualitative analyses is desirable and strongly recommended by qualitative scholars to strengthen credibility of the results (Polit & Beck, 2012). Third, themes and exemplars were compared across research team members. Differences in wording of the themes were fully explored (Patton, 2002). One investigator conducted a computer analysis using NVivo and coding of themes, which were confirmed by another investigator. Relevant discussions during conferences, transcribed interviews, raw data, and notes of activities during data collection can be traced through an audit trail ensuring auditability. Returning themes to participants for validation is a desirable step in some phenomenological approaches. The Giorgi approach does not require this step (Polit & Beck, 2012).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis (Patton, 2002; Polit & Beck, 2012; Sandelowski, 2008). Giorgi’s phenomenological approach included identifying significant statements from each transcribed interview, forming meanings, and then organizing the common patterns in clusters of themes in an iterative process constantly comparing them with the raw data to ensure accuracy.

Results

Demographic Results

Although 24 women consented to participate in the qualitative study, one woman was lost to follow-up and only 23 women completed the interview. The 23 women ranged in age from 18 to 38 years and were recruited and interviewed from February, 2008, to January, 2010. Seventeen women lived in Baltimore and six in the USVI. Ten to 15 participants is an adequate sample size to reach data saturation in qualitative studies (Sandelowski, 2008). Of the 23 women, 20 were pregnant and three were parenting with an infant that was less than 12 months of age. Those who were pregnant had gestational ages ranging from 15 to 39 weeks. Time since diagnosis of HIV ranged from one month to nine years, with an average of 2.5 years. Three women (13%) reported abuse experiences during pregnancy and 10 (43.4%) reported lifetime abuse. Six themes were identified.

Themes

The six themes identified are consistent with the HBM constructs: perceived vulnerability to HIV infection; feelings about getting tested for HIV; knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors after HIV diagnosis; disclosure of HIV status; living with HIV: positivity, strength, and prayer; and, experiences with physical and sexual violence. Pseudonyms were used to protect the women’s identities.

Theme 1: Perceived Vulnerability to HIV Infection

The women were interviewed during pre-natal visits when they had the HIV testing done. Women reported a perceived vulnerability to HIV infection prompted by the acknowledgement of their own and their partners’ risky behaviors. Women described risks related to their partner’s risk status, such as drug use or multiple partners, and their risk or vulnerability related to unprotected or forced sex, sexual activities with a partner known to be a drug user, or to have had multiple partners. As Kenya noted,

“I was mentally prepared because I knew I was at risk. My partner then was an intravenous drug user. I was not surprised because at the time I was living a mostly risky and unhealthy lifestyle …”

Some women knew that they could get infected with HIV, yet failed to take action to prevent infection. Perception of low risk prevented them from taking the necessary precautions to protect themselves. One Virgin Islander was HIV-positive as a result of vertical transmission from her mother and the others were previously diagnosed as positive prior to this pregnancy.

Theme 2: Feelings about Getting Tested for HIV

This theme described women’s experiences related to the decision to get tested, and what might have influenced their decisions to get tested. The decision to get tested for HIV for the majority of women was voluntary, even though the women could have opted out of getting tested. Some were unaware about their option to opt-out, and instead reported that they were given laboratory forms to have what they believed were “normal pregnancy” blood tests. After the testing was completed, they were informed of the results and they realized that HIV testing was included. Therefore, it seemed that the majority of the women in this sample did not make a deliberate decision to be tested for HIV, however, they welcomed the opportunity to be tested for their overall health. In spite of this, perceived benefits for the baby were an important and significant motivator for women to get tested for their health in general when given the choice to be tested. Anna noted,

“It was not optional to me. For the health of my baby and myself” and Chris said, “… more concerned about the baby versus me.”

Theme 3: Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors after HIV Diagnosis

This theme describes the emotions and feelings that the women recalled when they first learned of their HIV status. Many of the women who participated in this study learned of their status before their current pregnancy, which was not what the investigators had anticipated. Women reported a wide range of emotional experiences after they were informed of their HIV status, ranging from shock, anger, disbelief, fears and fear of dying, both for themselves and their unborn child. A few women had more positive responses to learning about their HIV-positive status and they described how their knowing their status had influenced their subsequent health practices. These emotions started with an initial shock and disbelief. Chris said,

“Oh my God, I am going to die,” “Baby [will] die.” “More afraid than anything, angry, concerned about baby versus me. Afraid, angry, and devastated.”

The anguish that some women felt after learning of their HIV status prompted concerns about the welfare of their children. As Anna reported,

“I am going to die. I am going to leave my kids - who am I going to leave them with? Just about my kids.”

Other women had positive attitudes and were making positive health-promoting steps to adhere to HIV treatments as well as adopting healthy lifestyles. Lizzy reported,

“Yes, I watch what I eat. I am more conscious … I stay healthy, I am taking my medicines.”

Theme 4: Disclosure of HIV Status

This theme demonstrated how women made decisions about disclosing their HIV-positive status, who they disclosed to, their own feelings about disclosure, as well as how those to whom they disclosed responded to them. Women were found to disclose their HIV status to family members first, followed by disclosing to friends. Cecilia reported,

“My friend Tasha. She hugged me and we cried together. She has not changed as my best friend … She told me everything would be alright.”

Yet, other women experienced feelings of anguish, sadness, and isolation from the reactions they received from family and friends. Kenya said,

“… they ostracized me and my kids and told my kids I was gonna die.”

The women did not provide specific reasons for disclosing to family members first. It was clear that the women who reported to family members or friends knew they will be supported. In addition, women did not report experiencing partner violence after disclosing their HIV status, so the authors did not find a direct link between HIV disclosure and partner violence. Nevertheless, some of the women’s fear to disclose to their partners after being diagnosed suggested that they might have feared some form of retribution. Other women were already in abusive relationships before being diagnosed with HIV.

Theme 5: Living with HIV: Positivity, Strength, and Prayer

Some women expressed their strong reliance on spiritual beliefs and faith in God to help them through the experience. They believed the situation was beyond their control, so they placed their fate in a higher power, demonstrating the women’s acceptance and strength in their faith. Chris reported,

“It is scary, but at the same time, you have to have faith, believe in yourself; have courage and pray.” “Spiritual faith is strong – [I am] more mature. [I] appreciate life more, little things. Pray every day for a cure.”

Clara noted that some women felt a sense of worth and increased confidence when they were pregnant and felt a sense of accomplishment. This renewed sense of self-worth lifted their depression,

“My depression got much better during the pregnancy because the baby gave me a lot to think about and a lot to plan and I was not depressed at all. I was happy. It was amazing …”

The majority of the Virgin Island women expressed strong beliefs in God but did not believe the church or the community would understand or be supportive, so they did not disclose their status to these groups. Maggie noted,

“It is very difficult here with the community about the HIV … they make a big deal about it.”

Theme 6: Experiences with Physical and Sexual Violence

This theme captured the women’s descriptions of traumatic events in their childhood and adulthood, which included a pervasive prevalence of interpersonal violence, potentially placing them at risk for HIV infection. One of the participants was raped by her boyfriend’s father, who was HIV positive. This demonstrated a strong link between sexual violence and HIV infection. Kenya reported,

“When I was younger … I got raped at 8 years …”

A related story was from Erica, who reported,

“I got HIV at 12, raped by my boyfriend’s father who was HIV-infected …”

Anna reported emotional and sexual abuse even before her pregnancy,

“… yes, before I was HIV, he abused me, we did not use protection during sex, no use of safe sex practices. Calls me names, puts me down and humiliates me.”

Discussion

This study contributes to nursing knowledge by providing additional evidence about the experiences of HIV-positive African-American and African Caribbean pregnant and parenting women. This study represents one of the first studies that included childbearing women of the USVI. This is particularly important as women of the USVI frequently travel to the mainland (USA) and receive care in that health-care system. Although the goal was to compare and contrast the women’s experiences from the two different settings, it was found that the women shared similar experiences. The findings from the study suggest that the women experienced complex and diverse situations regardless of the setting.

It was found that across the settings, women who acknowledged their partners’ high risk behaviors disclosed to them immediately. These study findings are similar to those who found the highest disclosure with partners (51.7%; n =116) (Peltzer, Chao, & Dana, 2008). Women may have felt that if their partners were engaged in risky behaviors, then they were the reason they got infected. Other women who disclosed to family members and close friends expected positive social support, motivating them to disclose their HIV status.

Women’s knowledge about HIV and available treatment options seemed to be most influential in their participation in testing. Twenty-two of the 23 women had at least one child before the current pregnancy and none felt the need to terminate the pregnancy, which is consistent with the findings of Kisakye, Akena, and Kaye (2010). All the women in this study received care in comprehensive clinics, which prepared them for healthy pregnancy and delivery experiences and may have resulted in the women having a better emotional outlook for their babies. Women reported that their decision to adhere to HIV treatment was strongly motivated by perceived benefits to their baby. Getting tested was important in order to enable them to start antiretroviral treatment early. Similar findings were reported by Craft et al., (2007), who found young pregnant women to be particularly concerned about transmitting the HIV to their unborn children. Other researchers have found similar results (Minnie, Klopper, & Walt, 2008).

Even though the current study did not explore stigma experiences, some women reported perceived feelings of isolation and fear that prevented them from disclosing. African Caribbean women were particularly aware of the stigmatization of people living with HIV/AIDS in the USVI and were reluctant to disclose their status to persons other than close family, friends, or health-care providers. Archibald reported similar findings in churchgoing African Caribbean people living in the United States (2010). The Virgin Islander women more frequently reported family, church, and community stigma related to HIV. Fear and stigma were the reasons that the older African-American adult participants in the southern United States failed to disclose their HIV infection (Foster & Gaskins, 2009). These results demonstrated that 13% (n = 3) of the women reported perinatal abuse and 43% (n = 10) reported lifetime abuse. The 13% reported in this study falls within the range of 0.9 – 20.1% reported by Coker, Sanders, and Doug (2004). These results are consistent with a population-based study that reported lifetime abuse at 28.9% (n = 6,790) among women (Coker et al., 2002).

Limitations of the Study

The study has limitations. First, the study targets the experience of childbearing African-American and African Caribbean women. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to non-childbearing women and other ethnic or racial groups. Second, some of the HIV-positive women were participating in comprehensive pregnancy programs, which may have influenced their feelings, their experiences about testing, about continuing the pregnancy, and treatment and health practices. These women may not represent the universe of other childbearing HIV-infected women. Third, the women resided in urban areas of the United States and the USVI, and their experiences may not represent the experiences of other HIV-positive childbearing women. Fourth, the women were of low socioeconomic status, and were not representative of women from diverse socioeconomic status. Even with these limitations, the findings provide insights into the experiences of HIV-infected low-income childbearing African-American and African Caribbean women and may be useful for informing practice and providing future directions for research.

Implications for Midwifery Practice

The insight gained from this study may be useful for midwifery care practices. The philosophy of midwifery care embraces respect for human dignity, individuality, and diversity among women receiving care, proving complete and accurate information to assist women in making informed decisions and involvement of the women’s designated family members in all health-care experiences (American College of Nurse Midwives [ACNM], 2010). The model of care promotes a partnership with the woman, acknowledging her life experiences and knowledge.

Midwifery care begins with comprehensive assessments, which should also include the women’s lifetime abuse experiences as well as current relationship status and partner abuse. Such assessments could occur during all phases of the women’s healthcare and is important for building trust and the women’s feelings of safety in disclosing abuse status to midwives. Midwifery care that offers focused counseling to provide women with accurate information about HIV testing and treatment options is important. The findings from this study suggested that women with this knowledge opted to get tested. Women also indicated that once knowing their status, they were motivated to initiate treatment, which was perceived as beneficial to their babies. Counseling could provide strategies to enhance social networks and empower women to safely disclose their HIV status and initiate HIV care and treatment interventions early.

The positive social support that the women reported they received from family and friends could have increased their motivation to perform health-promoting behaviors, which is supported in the HBM. Also important is the need for midwives to integrate the women’s spiritual beliefs and faith in motivating them to perform health-promoting behaviors. As this study demonstrated, women relied on their faith for strength to deal with the challenges they faced, as demonstrated in other studies (Minnie, Klopper, & Walt, 2008).

Midwives can also be active advocates for the healthcare policies that make comprehensive reproductive care available for all women. In an economy that threatens cuts to entitlement programs and other women’s health services, midwives can continue to advocate universal screening for intimate partner violence, and HIV testing and counseling, as part of women’s healthcare, including follow-up care for appropriate treatment options. This is critical given the high percentage of women in this study that reported lifetime abuse and who may have been unknowingly exposed to HIV.

Implications for Future Research

There are gaps in knowledge about what influences health practices of HIV-infected childbearing women, particularly women of African roots. Research is needed that identifies the heterogeneity of beliefs, cultural practices that influence the experiences of women related to testing, disclosure, continuing pregnancy, and adherence to treatment and parenting practices. Additional research is needed with diverse groups of women from other ethnic groups to explore more in-depth fear and stigma, as well as other negative and positive experiences.

There is a need for more prevention interventions that simultaneously address the complex interactions between interpersonal violence and HIV among childbearing women. Studies that include supportive cultural components, practices that promote positivity and prayer, and echo the voices of women in this study are warranted. Research that investigates what is required to support the women’s ability to safely disclose HIV status to partners and family members is also needed; as well as how to safely engage the support network in a manner that supports HIV treatment and reproductive care.

Conclusions

The women in this study expressed a variety of experiences related to their HIV and interpersonal violence status. Their experiences related to getting tested for HIV was contingent upon perceived vulnerability to HIV infection and perceived benefits to their unborn children. After getting tested, they faced many challenges related to disclosing their status. Disclosure considerations such as when, to whom, and the risks, were influenced by knowledge of their partner’s risky behaviors, as well as the social support they received. Through all these experiences, the women found that strong spiritual beliefs and positive attitudes gave them strength and resilience to cope with the complex situations they experienced related to their HIV status and interpersonal violence in their relationships.

Acknowledgements

Funding was obtained from the Caribbean Export Center for Health Disparities (R24 MD001123-02) and the Caribbean Exploratory NIMHD Research Center of Excellence (Grant # 5 P20MD002286), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities/NIH, University of the Virgin Islands.

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the following. From the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing - Mathew Hayat, PhD, Biostatistician; Amy Goh, RN, BSN, Iye Kamara, RN, BSN; and Ayanna Johnson, RN, BSN, Research Assistants; Nadiyah Johnson, Academic Program Coordinator. From the Caribbean Exploratory Research Center, University of the Virgin Islands, School of Nursing - Ophelia Powell-Torres, RN, MSN, Desiree Bertrand, RN, MSN, and Edris Evans, RN, BSN Research Assistants; Lorna Sutton, BA, MPA, Administrative Coordinator; and Tyra DeCastro, Administrative Assistant.

Contributor Information

Veronica Njie-Carr, University of Delaware School of Nursing, Newark, DE.

Phyllis Sharps, Department of Community Public Health, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, MD.

Doris Campbell, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, and Visiting Professor, Caribbean Exploratory NCMHD Research Center, School of Nursing, University of the Virgin Islands, St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands.

Gloria Callwood, Director Caribbean Exploratory NCMHD Research Center, School of Nursing, University of the Virgin Islands, St, Thomas, United States Virgin Islands.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Coyne-Beasley T, Doherty I, Stancil TR, et al. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;41(5):616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Nurse Midwives. Philosophy and scope of practice. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.mid-wife.org. [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO, Adimora AA, Fenton KA. Understanding and responding to disparities in HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in African Americans. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):337–340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald C. HIV/AIDS-Associated Stigma among Afro-Caribbean People Living in the United States. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;24(5):362–364. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore City Report. HIV/AIDS and African Americans. Baltimore City HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Profile. 2009 Ref Type: Online Source. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer TH, Zhao W, Metsch LR, Coltes A, Zenilman J. High-risk behaviors in women who use crack: knowledge of HIV serostatus and risk behavior. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17(7):533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV/AIDS and African Americans. 2010 Accessed from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2009. HIV Surveillance Report. 2011;21 [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt H, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Sanderson M, Doug B. Partner violence during pregnancy and risk of adverse outcomes. Paediatric & Perinatal Epidemiology. 2004;18(4):260–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft SM, Delaney RO, Bautista DT, Serovich JM. Pregnancy decisions among women with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11(6):927–935. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Khuzwayo N, et al. Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behaviour among young men in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS. 2006;20(16):2107–2114. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247582.00826.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PP, Gaskins SW. Older African American’s management of HIV/AIDS stigma. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1306–1312. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2007;8(2):178–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin S, Ahmed S, Ferguson L. Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling in health facilities—what does this mean for the health and human rights of pregnant women? Developing World Bioethics. 2008;8(1):23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanniappan S, Jeyapaul MJ, Kalyanwala S. Desire for motherhood: exploring HIV-infected women’s desires, intentions and decision-making in attaining motherhood. AIDS Care. 2008;20(6):625–630. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenbaum SB, Hirky AE, Correale J, Goldstein RB, Johnson MO, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. “Throwing the dice”: pregnancy decision-making among HIV-infected women in four U.S. cities. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(3):106–113. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.106.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisakye P, Akena WO, Kaye DK. Pregnancy decisions among HIV-infected pregnant women in Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2010;12(4):445–454. doi: 10.1080/13691051003628922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Dunbar MS, Minnis AM, Medlin CA, Gerdts CE, Padian NS. Poverty, gender inequities, and women’s risk of human immunodefi ciency virus/AIDS. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1136:101–110. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein B. Domestic violence, sexual ownership, and HIV risk in women in the American deep south. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(4):701–714. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minne K, Klopper H, Walt C. Factors contributing to the decision by pregnant women to be tested for HIV. Health Sa Gesondheid. 2008;13(4):50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. London: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health Promotion in Nursing Practice. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Chao LW, Dana P. Family planning among HIV positive and negative prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clients in a resource poor setting in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. (4th ed.) 2008;13(5):973–979. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9365-5. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rountree M, Mulraney M. HIV/AIDS risk reduction intervention for women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2008;38(2):207–216. doi: 10.1007/s10615-008-0183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski MJ. Justifying qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 2008;31(3):193–195. doi: 10.1002/nur.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Pagura J, Grant B. Is intimate partner violence associated with HIV infection among women in the United States? General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(3):274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among married Indian women. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(6):703–710. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson K. Explaining racial disparities in HIV/AIDS incidence among women in the US: A systematic review. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(20):4132–4143. doi: 10.1002/sim.3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgin Islands Department of Health HIV Surveillance. Online from: Virgin Islands Department of Health HIV Surveillance. (2010) Annual Report. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. World report on violence and health (ISBN 9241545615) Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]