Abstract

Primary care clinics are an ideal setting for early identification and possibly treatment of adolescent obesity. However, despite practice recommendations promoting preventive screening and monitoring of obesity, implementation has been modest. In this study we interviewed providers to determine barriers to managing pediatric obesity, perceived skill in obesity interventions, and interest in additional training. The sensitivity of weight-related discussions and time were the two most significant barriers reported. We designed a brief training program, implemented it within a larger randomized controlled trial, and surveyed providers regarding its utility. The training was satisfactory to attendees and led to reported changes in practice patterns. Providers who received more complete training reported greater ease working with overweight teens and greater confidence that they could motivate teen patients to make healthy lifestyle changes compared with those who received less training. A fairly modest training intervention could improve patient care in the primary care setting.

Keywords: adolescent, obesity, primary care provider

Adolescent obesity is a major public health concern and recent estimates suggest that in 2009-2010 more than 18% of adolescents (aged 12-19) were obese.1 Pediatric primary care clinics are an ideal setting for identifying and possibly treating overweight adolescents. Walker and colleagues2 found that of all topics teens wanted to discuss with their doctors, body size or shape was most often reported (30% of girls) and, following acne, diet, and exercise were third and fourth respectively (28% and 20% of girls). Research suggests that adolescents perceive their physicians as credible sources of medical information3 and expect them to address healthy weight management.4 This makes the pediatric primary care provider (PCP) a potentially effective agent of positive behavior change. PCPs have the opportunity to influence the attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge of their adolescent patients by providing them with accurate weight management information. Further, the chronic nature of obesity requires long-term treatment and, as continuous care providers, PCPs are well positioned to support the ongoing weight management efforts of their young patients. PCPs are likely to see the same child over time, and while single contacts may be brief, the repeated opportunities for intervention over the duration of the relationship can be cumulatively powerful. Although many providers acknowledge the opportunity primary care practice presents for managing pediatric obesity and believe weight counseling is within their purview, many feel ineffective and underprepared to address overweight and obesity with their adolescent patients.5;6 In a survey of pediatricians and family practice physicians sampled from the American Medical Association Masterfile, less than 50% of PCPs assessed BMI percentiles regularly and 58% reported never, rarely, or only sometimes tracking patients over time concerning weight or weight-related behaviors.7

The objectives of this study were to: (1)conduct a needs assessment among pediatric primary care providers to determine their perceived barriers to managing pediatric obesity, perceived skill in obesity interventions, and interest in additional training; (2) design a brief training program for providers; (3) implement the training within a larger randomized controlled trial; and (4) survey8 providers to assess how useful they perceived the training to be. We describe here the methods for conducting the formative needs assessment and the qualitative results that informed the provider training before describing the training and the follow-up survey results.

Needs Assessment Interview Methods

We recruited a convenience sample of 11 health care providers representing three treatment settings—a health maintenance organization, an academic medical center, and school-based healthcare—within the Pacific Northwest. The sample included pediatricians (73%) and nurse practitioners (27%) from primary care (82%) or school settings (18%). Each provider participated in a 45-minute semi-structured interview. Participants were asked to describe the extent of their work with overweight and obese youth, barriers or challenges they faced in dealing with these patients and their families, the practitioner’s general comfort addressing weight-related issues with patients and their families, and their typical recommendations for care. We audio-recorded and transcribed the interviews and then coded the text using the ATLAS.ti qualitative analytic software. All study procedures were approved and monitored by the Institutional Review Board.

Needs Assessment Results

A number of themes emerged from the data. The two most prominent were the sensitivity of weight-related discussions and time as barriers to treatment. Providers spoke of weight being a very difficult topic to discuss with their adolescent patients. Most providers used BMI charts or an open-ended question about weight to begin a discussion. From there, they judged non-verbal cues (i.e., body language, eye contact) in order to decide how to proceed:

“I usually try not to say anything more than just allow the NUMBER [weight] to kind of speak for itself. Usually I’ll say “Oh yeah. It’s kind of up there.” Then I’ll say “Well you know a couple of things that you might consider thinking about are eating habits and also how much activity you get.” Usually depending on what the answer is I’ll just stop if I’m not getting much feedback that says “Yeah, I’d kind of like to keep talking.”

“I see no value in pushing someone into a discussion that they’re not ready to have, I think that’s counterproductive. Those discussions where they’re [adolescent] ready to talk about it, usually just kind of take off and you find yourself having to actually put the brakes on, otherwise you’ve spent the whole morning, or the whole day, talking to that family about whatever because they get engaged. When there’s no engagement, to me that’s a signal, they’re not quite ready to go there. And it’s counterproductive to push.”

Several providers described frustration with lack of sufficient time to treat obesity. They reported that appointment times were too short to treat a chronic problem. A few providers reported wishing they had training in behavioral change techniques as they did not believe they were making satisfactory progress with their patients:

“… the most important thing is to have someone take the time to be able to engage in a longer discussion that helps to motivate and incent a desire to change. Because I can do just so much of that in one minute or three minutes and then I just have to stop.”

“With those very challenging kids that are very overweight, I feel like they need time. You know, they need more time, and that’s always a factor; we have ten minute appointments and you’re supposed to be talking about all these things. And I’m NOT an expert in it and I don’t have an expert to be able to refer to.”

“I think that talking about sexual activity is in some ways easier.”

It was apparent from the interviews that providers were seeking a model for more comfortably introducing weight related discussions and conducting them within the constraints of a typical office visit. We sought to provide such a model and resources in our training.

Provider Training Methods

The provider training was implemented as part of a larger randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a primary-care based, multi-component lifestyle intervention for overweight (≥ 90th percentile) adolescent females (SHINE).8 The intervention consisted of 16 group meetings (90 minutes each) over five months. Groups met weekly during the first three months and biweekly during months four and five. If unable to attend a particular group session, teens were offered telephone sessions. Over the first three months, parents were invited to separate weekly group meetings. At each session, teens were weighed and reviewed dietary and physical activity self-monitoring records. A full description of the multi-component intervention is elaborated in the main outcomes paper.8 In brief, the intervention included: (1) encouraging change in dietary intake and eating patterns, (2) increasing physical activity using developmentally tailored forms of exercise, (3) addressing other issues associated with obesity in adolescent girls (e.g., depression, disordered eating patterns, poor body image), and (4) training participants’ PCPs to support behavioral weight management goals collaboratively.

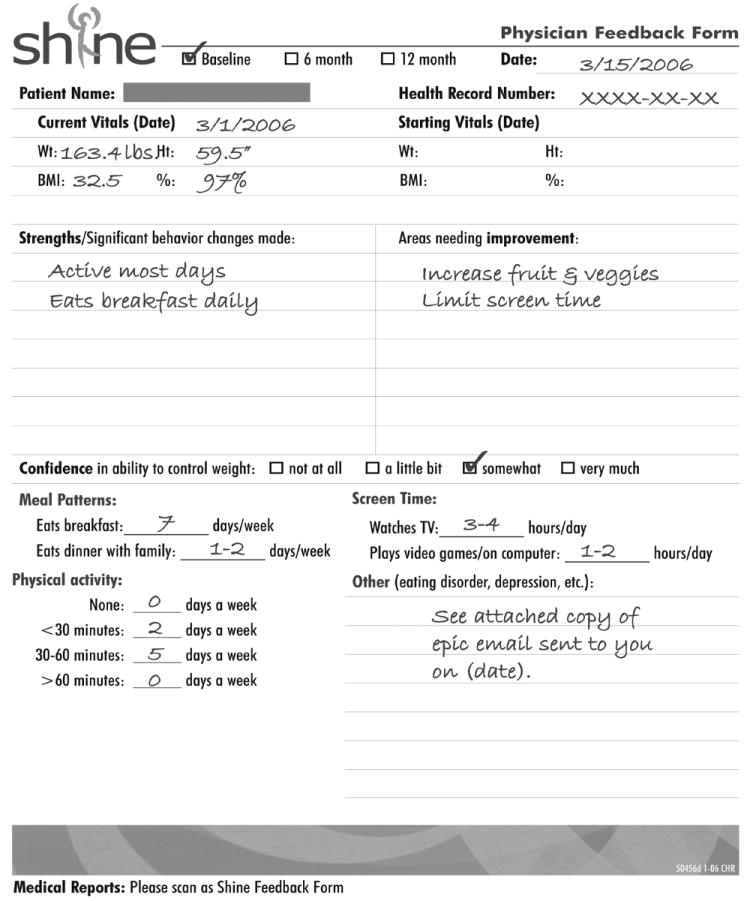

An essential and unique feature of the SHINE program was coordination of care with the pediatric primary care providers. A fundamental component was that providers received customized feedback regarding each of their patients enrolled in the intervention arm of the study. Prior to scheduled follow-up visits providers received summarized information gleaned from two study questionnaires—the baseline and follow-up assessments (see Figure 1). This tailored feedback included baseline and current height, weight, and BMI; significant behavior changes made and areas needing continued improvement; each adolescent’s perceived confidence in her ability to control her weight; meal patterns; physical activity patterns; screen time; and other participant-specific information. The three goals of the provider training were to: 1) promote provider confidence in motivating overweight teen patients to make healthy lifestyle changes, 2) provide resources and skills (motivational interviewing [MI] and brief negotiation) for addressing weight issues within a typical office visit structure, and 3) assist providers in fully utilizing tailored feedback about their patients’ weight management efforts.

Figure 1.

Physician feedback form.

A pediatrician who was a part of the investigator team led the training. We designed the training program to be implemented during two 90-minute sessions. In the first session, participants attended a presentation on how a pediatric primary care provider can help patients manage their weight. Recommendations included: collecting and reviewing objective feedback with patients, such as food diaries and lab test results; strengthening the patients’ commitment to positive behavioral change through MI using the FRAMES approach (provide feedback about personal risk, responsibility of patient, advice to change, menu of strategies, empathic style, and promote self-efficacy); brainstorming goals for healthy changes in diet and physical activity such as drinking fewer sweetened beverages and reducing screen time; reinforcing the importance of making healthy changes; expressing confidence in patients’ ability to make improvements, and sending home an after-visit summary with patient instructions. We recommended a structure that addressed the time constraints of short office visits and suggested a prototype weight-management visit. We also provided targeted instruction for using the feedback form to guide a patient visit.

For the second session, participants viewed a videotape created by the study team. The video demonstrated the study physician using an authoritarian, expert-based model to explore a mock patient’s motivation to lose weight. This was contrasted with the physician modeling the use of brief MI techniques with the mock patient. Both interventions were delivered within the brief office visit parameters. These distinct examples seeded a discussion about the pros and cons of using an MI approach to guide behavioral change with pediatric primary care patients and corrected the misconception that behavioral interventions need to be lengthy.

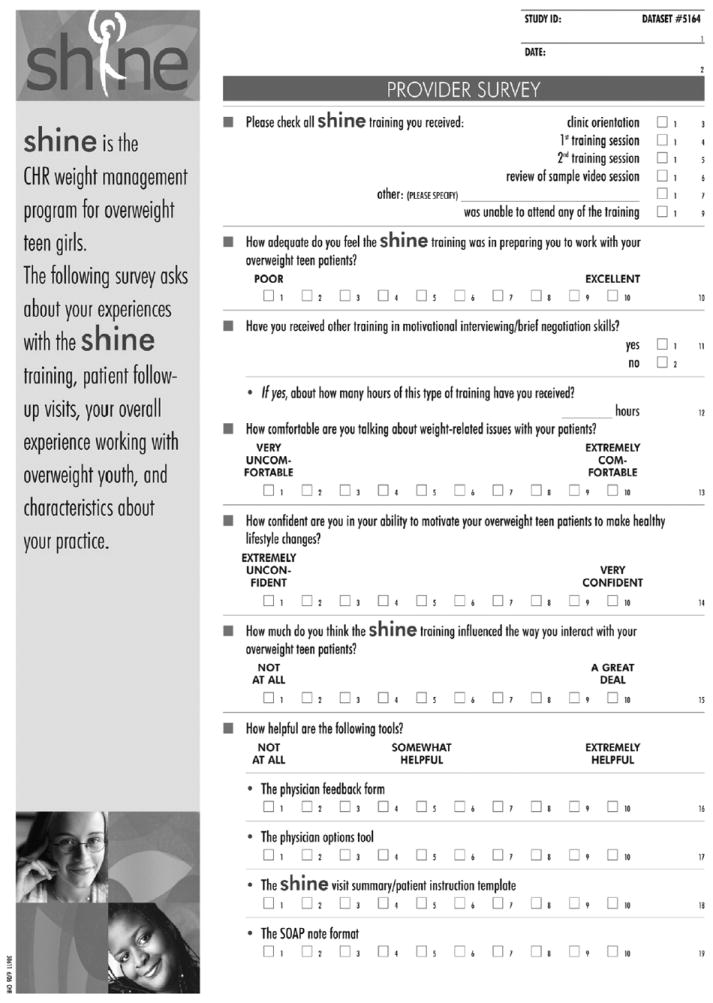

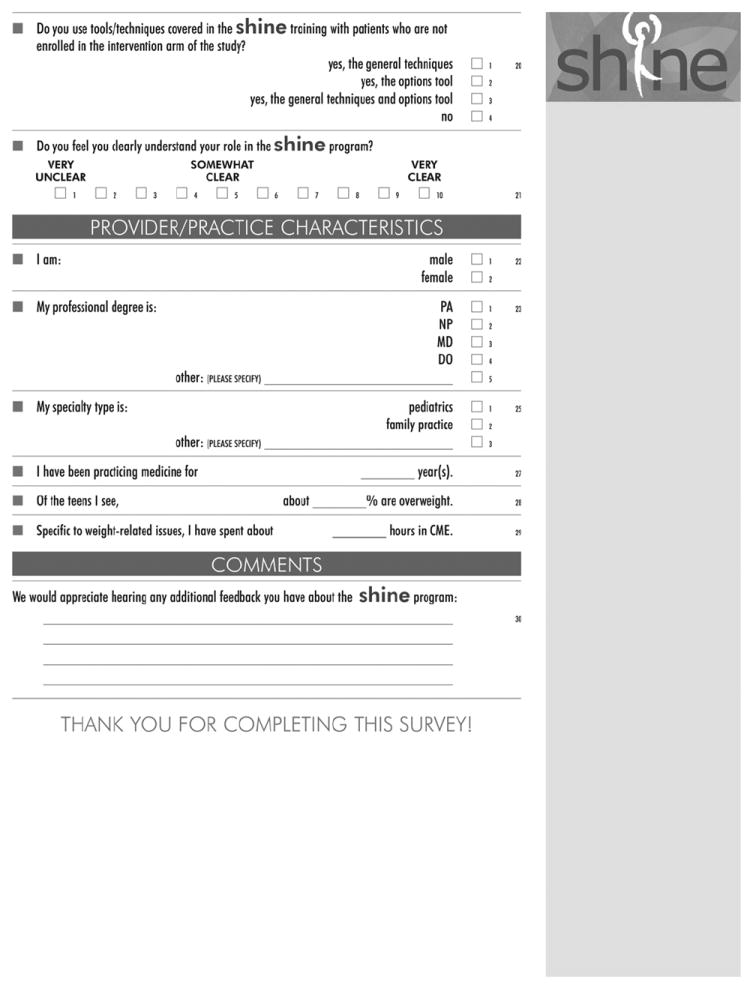

We mailed surveys to all primary care providers who attended the training or had patients enrolled in the SHINE clinical trial. All providers received the survey after having implemented the intervention with one or more study participants. The survey assessed providers’ practice characteristics as well as their satisfaction with the training and their perceptions about its utility (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Provider survey.

Provider Training Follow-up Survey Results

Of the 85 physicians with patients enrolled in the SHINE program who attended at least one training, 62 (73%) responded by returning a survey. Table 1 shows the characteristics of those respondents. Of the respondents, 28 (45%) attended both provider trainings and 34 (55%) completed at least one session. Table 2 compares practice patterns of those receiving partial training to those receiving complete training. Providers overall rated the training moderately adequate (mean= 6.28, SD= 1.99; with 1 being poor and 10 being excellent) in preparing them to work with overweight teens. However, there was a statistically significant difference (p>.0001) in ratings between those who received complete training compared with those who did not. Providers who attended the full training rated its utility higher (mean= 7.43, SD=1.26) compared with those who had only partial training (mean= 5.28, SD= 1.99). Regardless of exposure to the trainings, most providers reported comfort in talking about weight-related issues with their patients (mean= 7.61, SD= 1.6; 1= very uncomfortable, 10= very comfortable). Providers were less confident in their ability to motivate their overweight teen patients to make healthy lifestyle changes (mean= 6.11, SD= 1.66; 1 = extremely unconfident and 10 = very confident). They reported that study training moderately influenced the way they interacted with patients (mean= 5.75, SD= 1.95; 1 = not at all and 10 = a great deal).

Table 1.

Provider Characteristics

| Characteristic | n (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Gender (n=61) | ||

| Female | 45 (74%) | - |

| Specialty (n=58) | ||

| Pediatrics | 49 (84%) | - |

| Family Practice | 9 (16%) | - |

| Professional Degree (n=61) | ||

| MD/DO | 50 (82%) | - |

| NP/PA | 9 (15%) | - |

| Other | 2 (3%) | - |

| Mean years of medical practice (n=60) | - | 14.00 (8.77) |

| Mean hours of Weight management-related CME (n=47) | - | 9.15 (15.47) |

| Mean hours of previous training in Motivational Interviewing/ Brief Negotiation (n=35) | - | 7.26 (6.84) |

Table 2.

Pediatric Provider Survey Responses

| N | Incomplete Training Received Mean (SD) | Complete Training Received Mean (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Adequacy of provider training in preparation to work with overweight teens (1= poor, 10= excellent) | 60 | 5.28 (1.99) | 7.43 (1.26) | <.0001 |

| Comfort in talking about weight-related issues with patients (1= very uncomfortable, 10= very comfortable) | 62 | 7.47 (1.73) | 7.79 (1.45) | 0.45 |

| Confidence in ability to motivate overweight teen patients to make healthy lifestyle changes (1= extremely unconfident, 10= very confident) | 62 | 5.56 (1.50) | 6.79 (1.62) | .003 |

| Degree to which provider training influenced interaction with overweight patients (1= not at all, 10= a great deal) | 61 | 5.45 (2.08) | 6.11 (1.75) | 0.19 |

Discussion

We conducted this multiphase study to learn about pediatric primary care providers’ perceived practice barriers in managing adolescent obesity, perceived skill level in addressing weight management with their teen patients, and interest in additional training. Our formative research suggested that providers’ perceived barriers to treatment were consistent with those in the literature,5;9 that is, that their greatest challenges were the delicate nature of weight-related discussions with adolescent patients and lack of time to sensitively intervene during a regular office visit. Providers were seeking a model to efficiently and tactfully introduce discussions and interventions for their overweight patients. As part of a primary care based intervention for overweight adolescents we gave providers tailored feedback about their adolescent overweight patients’ progress in a lifestyle intervention for weight management. Based on feedback from interviews with providers, we conducted a training designed to 1) promote provider confidence in motivating overweight teen patients to make healthy lifestyle changes, 2) provide resources and skills (MI and brief negotiation) for addressing weight issues within a typical office visit structure, and 3) assist providers in fully utilizing tailored feedback about their patients’ weight management efforts. Most pediatric primary care providers in the regional health plan where this study was conducted participated in at least some portion of the training program and reported favorable impressions overall. Survey results suggest moderate changes in PCP practice patterns as a result of the training. PCPs who received complete training were significantly more satisfied with the adequacy of the provider training than those who received incomplete training. Providers who received more complete training reported greater ease working with overweight teens and greater confidence that they could motivate teen patients to make healthy lifestyle changes.

The focus of this research is important as this simple training intervention could improve patient care in the primary care setting. Further, because providers have an ongoing relationship with patients this support can be sustained over time. We found it fairly easy to implement our program. We attribute this to the involvement of two of our co-investigators who were practicing physicians in the health delivery system. Engaging these partners was likely a key to our success. Their ability to represent physicians’ perspectives and their keen awareness of the environmental particulars and potential barriers greatly shaped our approach to the training and the development of the feedback form. One of these providers led our training and both were able to be an ongoing presence in the health plan to answer questions about the study and to promote use of the feedback form. Providers were receptive to feedback and were able to incorporate it into their routine office visits. With continued use of technologies to extend the reach of health care, a future direction could involve online completion of assessments prior to a scheduled office visit which could result in summarized feedback provided to the physician in advance. Similarly, electronic devices employed in the waiting room, such as handheld devices or personal digital assistants (PDAs), could generate feedback to direct the course of the imminent visit. Further, healthy eating and exercise could be assessed within the context of broader age-relevant health targets (i.e., contraceptive management, helmet wearing, smoking cessation) and these targets could be addressed during the visit using the same model of MI and brief negotiation. In the Healthy Teens intervention, Olson et al. 10 utilized a PDA to administer a screener assessing interest in change and percieved confidence to change tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and risky alcohol use. Clinicians were trained in brief MI in a manner similar to the SHINE study. The authors reported that the use of this low-cost technology combined with promotion of patient-centered counseling influenced teens to increase exercise and milk intake. In addition to the potential to improve weight-related outcomes, there is also evidence to suggest that discussions of these types of relevant and, in some cases, sensitive health topics during primary care visits may have a positive impact on youth perceptions of care and on youth activation and engagement in treatment.11 It is feasible to expect that a similar program could be easily implemented in other practice settings. The training was minimally burdensome to providers and the costs of producing and conducting the training were modest. Costs would include the development of the training materials and compensation for the trainer.

Strengths and Limitations

This intervention was conducted in a single health maintenance organization and samples for both the formative interviews and the follow-up survey were small thus the generalizability of our findings is limited. In addition, we did not measure providers’ perceptions and behaviors before and after the training so we were unable to determine if this relatively simple training increased provider confidence or skill or if those factors improved patient outcomes. This paper describes one component of a much larger multi-component study8 and these hypotheses were not part of the planned analyses. Important next steps would be to replicate this study with larger samples in an alternative practice setting, such as private medical practice, and to measure the impact of the provider training in weight loss outcomes for patients.

Conclusion

After conducting a needs assessment, based on feedback we received, we created and conducted a brief training for primary care providers who treat overweight and obese adolescents. We determined that exposure to a modest intensity provider training intervention (two 90-minute sessions) led to reported changes in practice patterns and primary care providers felt reasonably comfortable discussing weight-related issues with their patients. This type of intervention could easily be provided as part of continuing medical education (CME) addressing pediatric obesity. The fact that nearly half of our sample had not had any training in brief MI and had spent very little CME hours in obesity-specific education suggests there is a need for this type of training.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues in the Pediatrics and Family Practice Divisions of Kaiser Permanente Northwest, without their assistance this study could not have been conducted. We also thank Dana Foley and Jill Pope for their helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number HD050931].

Contributor Information

Lynn L. DeBar, Email: lynn.debar@kpchr.org.

Philip Wu, Email: philip.wu@kp.org.

John Pearson, Email: john.pearson@kp.org.

Victor J. Stevens, Email: victor.stevens@kpchr.org.

Reference List

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker Z, Townsend J, Oakley L, et al. Health promotion for adolescents in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325:524. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7363.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry CL, Griffin G, Murray DM. Assessing needs for youth health promotion. Prev Med. 1985;14:379–393. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(85)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Health care information sources for adolescents: Age and gender differences on use, concerns, and needs. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:170–176. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Story MT, Neumark-Stzainer DR, Sherwood NE, et al. Management of child and adolescent obesity: attitudes, barriers, skills, and training needs among health care professionals. Pediatrics. 2002;110:210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrin EM, Vann JC, Lazorick S, et al. Bolstering confidence in obesity prevention and treatment counseling for resident and community pediatricians. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang TT, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. Pediatricians’ and family physicians’ weight-related care of children in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBar LL, Stevens VJ, Perrin N, et al. A primary care-based, multicomponent lifestyle intervention for overweight adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e611–e620. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrin EM, Flower KB, Garrett J, Ammerman AS. Preventing and treating obesity: pediatricians’ self-efficacy, barriers, resources, and advocacy. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5:150–156. doi: 10.1367/A04-104R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Lee PW, Starr P. Changing adolescent health behaviors: the healthy teens counseling approach. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S359–S364. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JD, Wissow LS. Discussion of sensitive health topics with youth during primary care visits: relationship to youth perceptions of care. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]