Abstract

Placebo response in clinical trials of antidepressant medications is substantial and increasing. High placebo response rates hamper efforts to detect signals of efficacy for new antidepressant medications, contributing to more failed trials and delaying the delivery of new treatments to market. Media reports seize upon increasing placebo response and modest advantages for active drugs as reasons to question the value of antidepressant medication, which may further stigmatize treatments for depression and dissuade patients from accessing mental health care. Conversely, enhancing the factors responsible for placebo response may represent a strategy for improving available treatments for Major Depressive Disorder. A conceptual framework describing the causes of placebo response is needed in order to develop strategies for minimizing placebo response in clinical trials, maximizing placebo response in clinical practice, and talking with depressed patients about the risks and benefits of antidepressant medications. This review examines contributors to placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials and proposes an explanatory model. Research aimed at reducing placebo response should focus on limiting patient expectancy and the intensity of therapeutic contact in antidepressant clinical trials, while the optimal strategy in clinical practice may be to combine active medication with a presentation and level of therapeutic contact that enhances treatment response.

Introduction

Placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials has recently captured the attention of psychiatric researchers, clinicians, and the lay public. Scientific interest focuses on the influence of placebo response on signal detection in clinical trials and what its physiologic mechanisms reveal about the pathophysiology of Major Depressive Disorder. The public would like to know whether responses to antidepressants are caused by specific effects of the medications or are “just” placebo effects. Clinicians may alternately view placebo response as a challenge to their decisions to prescribe antidepressant medication and a potential tool to improve patient care. Complicating much of this discourse has been a murky understanding of what contributes to placebo response in clinical trials. This review presents a model of placebo response in order to aid in the interpretation of randomized controlled trial results to clinical practice, set an agenda for future research, and help clinicians speak with their patients about antidepressant treatments.

The Problem and the Promise of Rising Placebo Response

In antidepressant trials for adults, placebo response averages 31% compared to a mean medication response of 50%, and it has risen at a rate of 7% per decade over the past 30 years (1). Children and adolescents with Major Depressive Disorder exhibit even higher rates of placebo response (mean of 46% compared to a mean medication response of 59%) that have also been increasing over time (2). High placebo response reduces medication-placebo differences and leads investigators to make methodological modifications (i.e., the use of multiple study sites to increase sample size) that increase measurement error, both of which make it more difficult to demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of a putative antidepressant agent over placebo. Consequently, the average difference observed in published antidepressant trials between medication and placebo has decreased from an average of 6 points on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) scale in 1982 to 3 points in 2008 (3). For most currently approved antidepressants, less than half of the efficacy trials filed with the Food and Drug Administration for regulatory approval found active drug superior to placebo (4–5). While not all trials failing to distinguish medication from placebo represent false negatives, meta-analyses of antidepressant trials suggest that high placebo response rather than low medication response explains most of the variability in drug-placebo differences (2). The increasing number of failed trials in recent years has made developing psychiatric medications progressively more time-consuming (average of 13 years to develop a new medication) and expensive (estimates range from $800 million to $3 billion per new agent) compared to medications for non-CNS indications (6). These considerations contributed to recent decisions by several large pharmaceutical companies to reduce or discontinue research and development on medications for brain disorders, prompting warnings of “psychopharmacology in crisis” (7).

From a different perspective, enhancing the therapeutic components leading to placebo response may be a way of improving the clinical treatment of patients with depression. Major Depressive Disorder affects approximately 120 million people worldwide (including nearly 15 million American adults each year) and is a leading cause of disability due to illness (8). With currently available treatments, many patients will not experience sustained remission of their depression (9). As described further below, treatment with antidepressant medication involves much more than simply dispensing a pill: an expectation of improvement is instilled in patients receiving treatment, and they are exposed to a health care environment that has many supportive and therapeutic features. These non-pharmacologic aspects of clinical management likely cause a substantial portion of observed medication and placebo response in clinical trials (10), yet they are typically not provided to the same extent in standard clinical practice. Whereas it was once believed that the therapeutic effects of expectancy and contact with health care staff were transient, more recent data show that 75% of placebo responders stay well during the continuation phase of treatment (11). Thus, optimizing the therapeutic components leading to placebo response has the potential to significantly improve treatment outcomes in clinical practice.

Differentiating the Placebo Effect from Placebo Response

“Placebo response” can be defined as the change in symptoms occurring during a clinical trial in patients randomized to receive placebo. Placebo response, which is directly observed and quantified in a research study, is often conflated with the term placebo effect. A “placebo effect” can be defined as the therapeutic effect of receiving a substance or undergoing a procedure that is not caused by any inherent powers of the substance or procedure (12). For example, an inert cream has no “inherent powers” to relieve pain, but being informed the cream is an analgesic may result in a person feeling less pain when a painful stimulus is applied because the expectation of pain relief causes the release of endogenous opiates in the brain. While placebo effects are one contributor to the placebo response observed in a research study, there are many other factors that may also influence placebo response.

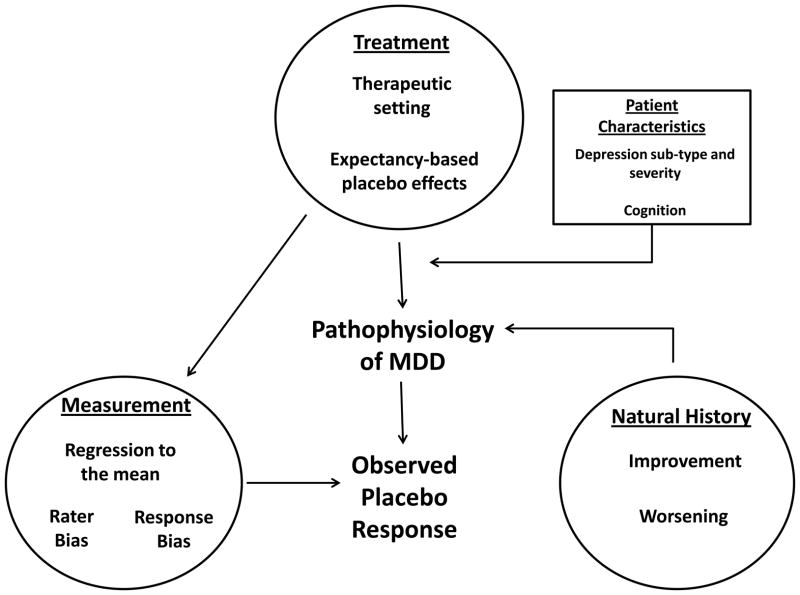

To clarify this differentiation further, the sources of symptom change in antidepressant clinical trials can be grouped into categories, which are depicted in Figure 1. Treatment factors comprise all the interventions and study procedures experienced by a patient in a clinical trial. Taking a pill believed to be an effective treatment for depression may generate a placebo effect (based on increased expectancy of improvement), while supportive contacts with study clinicians and undergoing medical procedures may also have therapeutic elements. Expectancy-based placebo effects and effects of the therapeutic setting may be moderated by demographic and clinical characteristics of participating patients. Measurement factors represent sources of bias and error inherent in measuring depressive symptoms, and natural history factors reflect spontaneous improvement and worsening in the patient’s condition that is unrelated to the study procedures. The symptom change observed in patient receiving placebo in a clinical trial (i.e., placebo response) is caused by the sum effects of these factors and their interactions. While large placebo effects may lead to large observed placebo response, it is also possible that high placebo response could be observed even where there are minimal placebo effects operative (i.e., if there has been substantial improvement resulting from the therapeutic setting, regression to the mean, rater bias, or spontaneous fluctuation in illness severity).

Figure 1.

A Model of Placebo Response in Antidepressant Clinical Trials.

Treatment Factors Contributing to Placebo Response

Expectancy-based placebo effects

Two theoretical approaches to understanding the mechanisms of placebo effects have been expectancy theory and classical conditioning (12). Expectancy theory postulates that placebo treatments instill a (conscious) positive expectation of improvement in the patient that actually causes the change in a patient’s symptoms. Conditioning theorists hold that placebo responses represent a type of non-conscious learning in which an individual associates improvement in symptoms (unconditioned response) with neutral stimuli such as pills, health care providers, or procedures (conditioned stimulus) that themselves become capable of eliciting an effect (conditioned response). In general, both conscious expectancy and non-conscious conditioning mechanisms likely contribute to the placebo effects observed in pharmacologic studies. However, given the importance of verbal information in shaping placebo effects and the fact that substantial placebo effects are observed in treatment-naïve patients, most empirical studies of the mechanisms of placebo effects in antidepressant clinical trials have focused on patient expectancy.

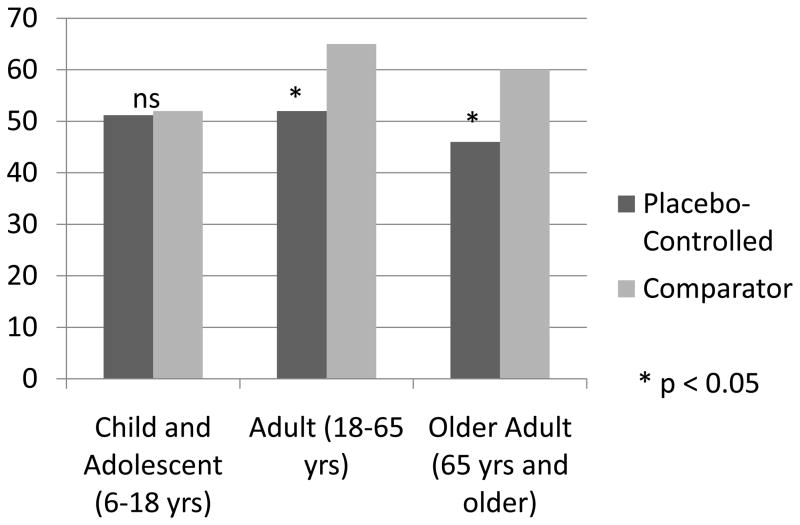

Khan et al (2004) first reported that the number of treatment arms in a study was negatively correlated with the “success” of the trial (defined as finding a significant difference between drug and placebo) (13). A greater number of treatment arms increases the probability of receiving active medication, which may increase patient expectations and generate higher placebo response. The influence of patient expectancy on antidepressant response also has been observed in comparisons of medication response between placebo-controlled trials (i.e., one or more medications compared to placebo) and active comparator trials (i.e., one or more medications with no placebo group). In adults and older adults with Major Depressive Disorder, mean medication response rates in comparator trials are significantly greater than the mean medication response rates in placebo-controlled trials (14–15). Patients in comparator trials know they have a 100% chance of receiving an active medication, which may increase their expectancy of improvement, leading to enhanced placebo effects and greater observed antidepressant response.

Consistent with these results, Papakostas and Fava (2009) reported that the probability of receiving placebo in a clinical trial was negatively correlated with antidepressant and placebo response (16). For each 10% decrease in the probability of receiving placebo, the probability of antidepressant response increased 1.8% and the probability of placebo response increased 2.6%. Similarly, Sinyor et al (2010) evaluated 90 randomized controlled trials of antidepressant medications for unipolar depression, comparing response and remission rates between trials comparing medication to placebo (drug-placebo), two medications to placebo (drug-drug-placebo), and one medication to another (drug-drug) (17). They found that medication response was significantly higher in drug-drug studies (65.4%) compared to drug-drug-placebo studies (57.7%) and drug-placebo studies (51.7%) (p < 0.0001). Response to placebo in placebo-controlled trials was significantly higher in drug-drug-placebo studies compared to drug-placebo studies (46.7% vs. 32.2%, respectively, p = 0.002).

The meta-analytic results suggest that the design of a clinical trial shapes patients’ expectancies of improvement during the trial, which in turn influence response to antidepressant medication and placebo. However, the veracity of this interpretation must be tested in studies which directly measure patient expectancy in different types of antidepressant clinical trials and determine the relation of expectancy to treatment outcome. Two studies measuring patient expectancy at baseline reported that higher expectancy predicts greater symptom improvement during treatment of depression with antidepressant medication (18–19). Moreover, a recent pilot study experimentally manipulated expectancy in subjects with Major Depressive Disorder by randomizing 43 adult outpatients to placebo-controlled (i.e., 50% chance of receiving active drug) or comparator (i.e., 100% chance of receiving active drug) administration of antidepressant medication (20). Randomization to the comparator condition resulted in significantly increased patient expectancy relative to the placebo-controlled arm of the study (t = 2.60, df 27, p = 0.015). Among patients receiving medication, a trend was observed for higher pre-treatment expectancy of improvement to be positively correlated with the change in depressive symptoms observed over the study (r = 0.44, p = 0.058). The manipulation of expectancy in this study permits the causal inference to be made that more positive expectancy leads to greater improvement in depressive symptoms, both within a single type of clinical trial and between different trial types.

In summary, the consent procedure for pharmacotherapy trials, in which prospective participants become aware of the study design, the past effectiveness of the drugs and placebos used in the study, and the investigator’s opinions of the treatment options, influences patients’ expectancies of how participation in a clinical trial will affect their depressive symptoms. Expectancy appears to be a primary mechanism of placebo effects and significantly influences both observed placebo response as well as antidepressant medication response. In both treatment groups, patients are receiving a pill that they believe may represent a treatment for their condition.

Therapeutic setting

Since the ability to generate treatment expectancies requires relatively advanced cognitive capacities, it is puzzling to observe high placebo response in children with depression. Compared to adults, participants in pediatric Major Depressive Disorder trials are less cognitively equipped to understand the nature of the study in which they are participating, and they actually receive less information at the time of their enrollment into the study (since their parents provide informed consent). To evaluate the significance of expectancy effects in younger patients, Rutherford et al (2011) analyzed antidepressant response between comparator and placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants for children and adolescents with depressive disorders (21). Contrary to the large differences observed between these study types in adults and older adults with depression, there was no significant difference in medication response between comparator and placebo-controlled studies enrolling children and adolescents.

Rather than patient expectancy, what appeared to influence treatment response was the amount of therapeutic contact patients received: adolescents experienced greater placebo response as the number of study visits increased. In an antidepressant clinical trial, patients experiencing social isolation and decreased activity levels as part of their depressive illness enter a behaviorally activating and interpersonally rich new environment. They interact with research coordinators and medical staff, receive lengthy clinical evaluations by highly trained professionals, and are provided with diagnoses and psycho-education that explain their symptoms. Medical procedures are performed, such as blood tests, electrocardiograms, and vital sign measurements. Finally, clinicians meet with patients weekly to listen to their experiences and facilitate compliance by instilling faith in the effectiveness of treatment.

Considerable empirical evidence supports the therapeutic effectiveness of these interventions. Optimistic or enthusiastic physician attitudes, as compared to neutral or pessimistic attitudes, are associated with greater clinical improvements in medical conditions as diverse as pain, hypertension, and obesity (22). A therapeutic relationship in which clinicians provide patients with a clear diagnosis, give them opportunity for communication, and agree on the problem has been shown to produce faster recovery (23). In addition, physical aspects of the treatment such as the pill dosing regimen, the color of pills, and the technological sophistication of the treatment procedures can influence treatment response (24).

Posternak and Zimmerman (2007) investigated the influence of therapeutic contact frequency on antidepressant and placebo response in 41 RCTs of antidepressants for MDD (25). These investigators calculated the change in HRSD scores observed over the first 6 weeks of treatment in patients assigned to antidepressant medication and placebo, comparing studies having 6 weekly assessments (weeks 1–6) to those having 5 (weeks 1–4 and 6) and 4 (weeks 1–2, 4, and 6) assessments. Participants treated with placebo who returned for a week 3 visit experienced 0.86 greater reduction in HRSD scores between weeks 2 and 4 compared to those who did not, while participants having a week 5 visit had 0.67 greater reduction in HRSD scores between weeks 4 and 6 compared to those who did not. A cumulative therapeutic effect of additional follow up visits on placebo response was found: between weeks 2 and 6, patients with weekly visits improved 4.24 HRSD points, while those with 1 fewer visit improved 3.33 points and those with 2 fewer visits improved 2.49 points. Thus, the presence of additional follow up visits appeared to explain approximately 50% of the symptom change observed between weeks 2 and 6 among patients receiving placebo. Participants receiving active medication also experienced more symptomatic change with increased numbers of follow-up visits, but the relative effect of this increased therapeutic contact was approximately 50% less than that observed in the placebo group.

The intensive therapeutic contact found in clinical trials may be contrasted with what patients being treated with antidepressants receive in the community. In community samples of patients receiving antidepressant medication, 73.6% are treated exclusively by their general medical provider as opposed to a psychiatrist (26). Fewer than 20% of patients have a mental health care visit in the first 4 weeks after starting an antidepressant (27), and fewer than 5% of adults beginning treatment with antidepressant medications have as many as 7 physician visits in their first 12 weeks on the medication (28). Thus, assignment to placebo in an antidepressant clinical trial represents an intensive form of clinical management that has therapeutic effects.

Methods of controlling for expectancy and the therapeutic setting in clinical trials

Greater patient expectancy and therapeutic effects of the health care setting lead to increased placebo response and, to a lesser degree, increased medication response. A ceiling is placed on potential medication response by the relatively constant proportion of the sample who will not respond to treatment (due to diagnostic misclassification, treatment refractoriness, etc.). Since increased placebo response thereby decreases medication-placebo differences, investigators have sought to identify methods of minimizing placebo response (and the component of medication response caused by placebo response) as a means of improving signal detection in clinical trials. One strategy for dealing with expectancy-based placebo effects and therapeutic responses to the health care setting has been to conduct single-blind lead-in periods aimed at identifying and excluding participants whose symptoms respond quickly to placebo. Multiple analyses have determined that such lead-ins have not been effective in reducing placebo response or improving detection of drug-placebo differences (21, 29–30). However, one study suggests that double-blind lead-in periods, in which study personnel are also blinded to the duration of placebo lead-in, may be more effective (31).

Measurement Factors Contributing to Placebo Response

In most clinical trials, investigators assess change in the severity of patient’s depressive illness based on symptom changes that are self-reported by patients or elicited by trained raters. Measurements of depressive symptoms are subject to random error like any other measurement, but unlike more objective measurements, such as serum cholesterol or blood pressure, depression symptom severity scores also may be subject to additional sources of bias. Conceptually, one can distinguish cases in which a patient’s depression score decreased because his depressive illness actually improved from cases in which the score changed for other reasons.

Regression to the mean

One source of apparent symptom change in antidepressant trials is regression to the mean, which is a statistical phenomenon occurring when repeated measurements associated with random error are made on the same subject over time (32). To illustrate, one can imagine that if an individual with a “true” Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) score of 10 underwent repeated ratings, a normal distribution with a mean of 10 would be obtained due to random error in measurement. If the initial value obtained happened to be unusually high or low, then the next observed value likely would be closer to the subject’s true mean score of 10 based on chance alone. Regression to the mean poses a problem at the group level in clinical trials, because a threshold depression severity score is set as an inclusion criterion (e.g., HAM-D > 16). Some of the individuals included in the study actually have true means below 16, and the tendency for the depression scores of these subjects to decrease on repeated measurement will give the appearance of group-level improvement when in fact no true change has occurred. This decrease in mean HAM-D scores will not be offset by a corresponding “upward” regression to the mean in those individuals whose HAM-D scores were initially underestimated, because these individuals will have been excluded from participation in the study.

Sources of bias

Rater bias occurs when an individual’s rating of symptom severity in an antidepressant clinical trial is influenced by underlying beliefs or motivations with respect to the treatments under study (33). For example, clinical raters typically perceive more symptom change in response to treatment than is self-reported by patients, possibly reflecting an excessive enthusiasm for detecting effects of the treatment under study (34–36). Assessments of eligibility for a clinical trial may be biased toward baseline score inflation when investigators have a financial incentive to recruit patients (37). Evidence for baseline score inflation comes from studies comparing clinician-administered HAM-D data with self-reported HAM-D scores obtained using interactive voice systems (38–39). These studies have found that clinician-rated HAM-D scores are significantly greater than self-reported scores at the time of patient enrollment, while the two assessment methods yield converging scores following randomization. This suggests that investigators are influenced, perhaps unconsciously, by the financial and professional returns accruing from an enrolled patient vs. a screen failure to increase their ratings of baseline depression severity.

Conversely, a response bias in psychological measurement is the systematic tendency of a subject to respond to questionnaire items on some basis other than what the items were designed to measure (40). Response bias occurs when respondents choose the response they perceive to be the most socially desirable or that is favored by the clinicians in a research study. The term “demand characteristics” has been used to describe cues that make participants in a research study aware of what results the experimenters hope to find, which can result in the participants altering their responses to conform to the researchers’ expectations (40). “Hawthorne effects” are a closely related phenomenon whereby subjects in an experiment improve or modify the aspect of their behavior under study simply by virtue of knowing the behavior is being measured (40). Response bias can be more problematic in antidepressant clinical trials compared to studies of non-psychiatric disorders due to the inherently subjective nature of rating illness severity based upon the verbal reports of patients.

Methods of minimizing measurement factors in clinical trials

Effect sizes for antidepressant medications relative to placebo are calculated by dividing the quotient of the mean improvement in the medication group and the mean improvement in the placebo group by the pooled standard deviation of the sample ([ImprovementMedication − ImprovementPlacebo]/Standard Deviation). As measurement error (and standard deviation) increases, the calculated effect size for antidepressant medication decreases, and the likelihood of detecting a statistically significant benefit of medication over placebo decreases. Thus, it is important for signal detection in antidepressant clinical trials to reduce measurement error. The primary method to reduce measurement error in antidepressant clinical trials is to institute a comprehensive and ongoing rater training program, in which inter-rater reliability is carefully measured and maintained at a minimum level. Unfortunately, information regarding inter-rater reliability in antidepressant clinical trials is almost never provided in published reports (41).

The problems posed by regression to the mean and rater bias (particularly baseline score inflation) in antidepressant clinical trials have been approached in several ways (42). One strategy involves specifying a minimum depression severity score required for enrollment into the study but then a priori setting a higher score threshold required for inclusion of the subject in the data analysis. Another technique is to blind raters at individual study sites to the timing of baseline assessment so that they are unaware which ratings will be used to ascertain patient eligibility for the study. Finally, many investigators now utilize two separate depression rating scales for clinical trials: one measure to determine subject eligibility, and a different scale to serve as the primary outcome measure in analyses.

A variant of these strategies is to utilize centralized raters to perform the screening and outcome measures in clinical trials (42). Using centralized raters provides investigators with access to a group of highly trained raters that are not often available to individual study sites. Centralized raters are less prone to bias by virtue of their off-site location and blinding to study entry criteria, patient phase of treatment, and treatment assignment. Thus, the use of centralized ratings may improve inter-rater reliability, relieve pressure to enroll patients, reduce biases toward baseline score inflation and observing improvement, and eliminate effects of repeated assessments by the same clinician. A relative disadvantage of using centralized raters is the necessity of assessing patients remotely via video conference or telephone rather than having a face to face interview.

Natural History Factors Contributing to Placebo Response

Given the ethical difficulties associated with following the untreated course of depression, few prospective non-intervention studies using modern diagnostic criteria exist that may be used to estimate the magnitude of spontaneous improvement that can be expected in acute depressive episodes (43). Alternate sources of information about the natural course of depressive disorders are psychotherapy studies utilizing a “wait-list” control group as a means of determining whether psychotherapy has an effect on depression beyond the passage of time. A recent meta-analysis of acute symptom change in wait-list control conditions found that individuals with Major Depressive Disorder experience an average improvement of 4 HAM-D points (Cohen’s d effect size = 0.5) over a mean follow up duration of 10 weeks (44). For comparison, meta-analyses of medication and placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials report standardized effect sizes of approximately 1.5 for medication conditions and 1.2 for placebo conditions (10). Thus, patients in wait-list control conditions experience approximately 33% of the improvement occurring with medication treatment and 40% of the improvement seen with placebo administration.

It is intriguing to speculate that natural history factors may be playing an increased role in antidepressant clinical trials over time as the population of patients enrolling in research studies changes. Most research participants in the 1960s and 1970s were recruited from inpatient psychiatric units, while current participants are symptomatic volunteers responding to advertisements (45). Studies are needed to compare the baseline characteristics, treatment response, and attrition rates of self-referred depressed patients compared to those who respond to advertisements. Natural history factors may be more important among the latter population, with the symptoms experienced by advertisement respondents being more variable and transient, resulting in increased placebo response rates, compared to self-referred patients.

It may be possible to mitigate natural history factors by requiring longer durations of current illness for inclusion in antidepressant trials, but the spontaneous fluctuation of depression severity is less subject to investigator control than measurement factors. Epidemiologic studies show that patients with Major Depressive Disorder typically experience symptoms for several months prior to seeking treatment (46). Patients are most likely to seek treatment during periods of increased stress or symptomatic worsening, so those who enroll in a clinical trial at this time of peak symptomatology may experience natural waning of symptoms or alleviation in the precipitating stressors irrespective of the treatment they are provided.

Patient Characteristics Moderating Placebo Response

Expectancy-based placebo effects are dependent upon intact cognition in order to generate placebo response (47), and a physiologic pathway must exist by which expectancy can influence the illness (i.e., minimal placebo effects are observed on tumor regression in metastatic cancer). However, among cognitively intact patients with depression, research has failed to identify consistent characteristics of patients likely to respond to placebo, giving rise to the term “the elusive placebo reactor” as early as the 1960s (48). Patient characteristics such as neuroticism, suggestibility, introversion, intelligence, and self-esteem have not been found to have significant associations with response to placebo (49). This has led many to reject the hypothesis that certain people respond to placebos while others do not, and instead the consensus view arose that most individuals appear capable of being influenced by placebo effects under the appropriate conditions (50).

While evidence for patient characteristics influencing placebo response has been limited, features of the depressive illness being treated appear to influence the magnitude of placebo response observed in an antidepressant clinical trial. One of the most replicated findings in recent years has been that placebo response decreases with increasing severity of baseline depression scores. Both Kirsch et al (2008) and Fournier et al (2010) found that placebo response significantly declined as baseline HAM-D increased (particularly as it exceeded a score of 25) (51–52). Other studies suggest that patients suffering from Major Depressive Disorder with Psychotic Features (53) and Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder (54) have decreased rates of placebo response, as do elderly depressed patients with early-onset (prior to age 60) depression (55).

Relationship of Placebo Response to Medication Response in Antidepressant Clinical Trials

A fascinating and important question in pharmacologic treatments is how to conceptualize the contribution of placebo response to medication response. “Medication response” denotes the change in symptoms occurring during a clinical trial in patients randomized to receive medication. In contrast, the “medication effect” is the specific physiologic effect of the medication being studied on the target disorder (e.g., the effect of serotonin reuptake inhibition on Major Depressive Disorder). By extension from Figure 1, medication response represents a combination of the specific medication effect with the previously described sources of placebo response (i.e., expectancy-based placebo effects, effects of the therapeutic setting, measurement factors, and natural history factors). The simplest and most common way to understand the nature of this combination is to assume that medication effects are additive with placebo response (i.e., placebo response is the same in the medication and placebo groups). In other words, if the observed placebo response in a clinical trial is 30% and the observed medication response is 50%, then the specific effects of the medication account for 50%–30% = 20% of the observed response. If the specific effects of medication are relatively constant between similar patient samples, differences in observed medication response between different types of antidepressant studies (e.g., placebo-controlled, comparator, open) would presumably be caused by differences in expectancy-based placebo effects and other non-pharmacologic factors.

The logic of clinical trials and their application to clinical treatment are based upon this “assumption of additivity” (56): medications are approved for use after demonstration of a significant difference compared to placebo, and the “number needed to treat” is calculated relative to placebo response. It is therefore surprising that there exists little to no evidence in the pharmacologic treatment of Major Depressive Disorder to prove that medication effects and the placebo response are additive. Equally possible is that all of the observed medication response is caused by the specific medication effect without any contribution from placebo response, in which case the medication effect would be substantially larger than that calculated based on additivity. Alternately, the presence of interactions between medication effects and sources of placebo response could result in the true contribution of medication effects to medication response being smaller than previously thought. For example, experiencing side effects known to be caused by the medication under study may “unblind” patients during a clinical trial, increasing their expectancy of improvement and leading to larger expectancy-based placebo effects.

To answer the question of how medication effects combine with sources of placebo response, it is necessary to conduct studies designed to test the assumption of additivity in antidepressant clinical trials. Kirsch (1990) has suggested that a modified form of the balanced placebo design may serve this function by randomizing a sample of patients with Major Depressive Disorder to be told they are receiving active medication vs. told they are receiving placebo (57). Each group is then further randomized to actually receive medication or placebo, allowing one to estimate the true drug effect by comparing response in the “Told Placebo/Receive Medication” and “Told Placebo/Receive Placebo” groups. Utilizing an active placebo with this study design would make it possible to control for unblinding by side effects as well. While this study design represents a cogent approach to disentangling medication effects from placebo response, ethical concerns with the temporary deception of depressed patients entailed in the balanced placebo design have precluded its use to date.

Alternatively, new statistical approaches have been developed to more accurately estimate the causal effect of medication on depression using standard clinical trial data sets. Muthen and Brown (2009) conceptually delimit four types of patients in a randomized controlled trial: those who would not respond to medication or placebo (‘Never responders’), those who would respond to both medication and placebo (‘Always responders’), those who would respond to medication but not placebo (‘Medication only responders’), and those who would respond to placebo but not medication (‘Placebo only responders’) (58). ‘Drug only responders’ are the group of interest to pharmacologic researchers, since these subjects are assumed to be experiencing a true medication effect. ‘Placebo only responders’ result from subjects experiencing adverse effects to medication, and they are assumed to be few in number. Applying growth mixture modeling with maximum-likelihood estimation to an antidepressant clinical trial data set, the authors report a method resulting in larger effect size estimates for ‘Drug only responders’ compared to conventional analyses. While this approach appears promising, it is not clear that it accounts for the possibility of interactions between medication effects and placebo response described above.

It appears likely that the specific effect of medication is at least partially additive with placebo response, though its precise magnitude cannot be determined without knowing whether there are significant medication effect x placebo response interactions. The considerations discussed in this section make clearer how rising placebo response makes it difficult to demonstrate statistically significant benefits of medications over placebo. First, rising placebo response leads to decreased medication-placebo differences (3), because the group of patients who do not respond to medication or placebo (i.e., ‘Never responders’) place a ceiling on medication response in an antidepressant clinical trial. An increase in placebo response thereby causes a corresponding decrease in the medication-placebo difference. Second, investigators have attempted to compensate for the decreasing effect sizes observed for antidepressant medication by employing multiple study sites to obtain larger sample sizes. The increased measurement error associated with multicenter clinical trials leads to decreased effect sizes for medication and often offsets the benefits of greater sample size.

Implications for the Antidepressant-Placebo Controversy

Media coverage of placebo response has been used as a platform for critiques of the pharmaceutical industry and a stalking horse for questioning the efficacy of antidepressants. For example, a recent “60 Minutes” report on CBS titled “Treating Depression: Is There a Placebo Effect?” (59) focused on a meta-analysis of 35 clinical trials of 4 antidepressants for Major Depressive Disorder published in 2008 (52). Standardized mean effect sizes were calculated for the pre-post symptom change observed in participants randomized to antidepressant medication and placebo, resulting in an effect size of 1.24 for medication and 0.92 for placebo (p < 0.001). However, when standardized mean differences between drug and placebo were examined as a function of initial depression severity, the difference in mean effect size exceeded the threshold for a “clinically significant” difference (defined as an effect size difference of 0.5) only among patients with a baseline HAM-D score ≥ 28.

Criticism of this meta-analysis has focused on its relatively small and selective sample of the available studies. In addition, comparing overall mean differences between drug and placebo groups does not account for different trajectories of treatment response (60) and is relatively insensitive to large and significant changes experienced by subgroups of the sample (61). However, other analyses using different methods and samples have reported similar findings, suggesting that the mean HAM-D difference between antidepressant medication and placebo may be modest for patients with milder depression (51).

A frequent conclusion drawn from these studies by the media as well as the public is that “antidepressants do not work better than no treatment at all”. This conclusion represents an incorrect interpretation of the data, which may have the dangerous public health consequence of dissuading patients with depression from accessing treatment. First, patients receiving antidepressants in clinical trials improve a great deal—the standardized mean effect size of 1.24 for antidepressant treatment is large. Second, being assigned to placebo in an antidepressant trial is far from “no treatment,” since it entails intensive contact with health care staff that greatly exceeds what is delivered in standard community treatment. More accurately, the above meta-analytic findings suggest that eliciting placebo effects and providing a therapeutic setting are powerful treatments for mild to moderate depression, and the specific effects of antidepressant medication result in small additional decreases in HAM-D scores over these interventions.

In order to benefit from placebo effects and a therapeutic setting, patients must receive some type of treatment. Most psychiatrists would agree that deception and the covert prescription of placebo are unethical for patients with depression. The question facing clinicians then becomes: of currently available treatments, what is the optimal way to elicit placebo effects and provide a therapeutic setting for patients with milder forms of depression? Some policy-makers have advised utilizing psychotherapy as the initial treatment approach, presumably as a means of eliciting placebo responses without the cost and potential side effect burden associated with antidepressants (62). While this may be reasonable for some patients, we would caution against blanket recommendations in favor of a thoughtful consideration of the risks and benefits of medication and psychotherapy for each individual. Psychotherapy is not always cheaper than antidepressant medication—analyses of their comparative cost-effectiveness have mostly shown minimal differences (63), and in some populations psychotherapy may be more expensive than medication as a treatment for depression (64). Like medication, psychotherapy may be associated with significant side effects, such as worsening symptoms and the fostering of dependence and regression (65). Finally, both psychotherapy and antidepressant medication may have therapeutic effects beyond merely decreasing HAM-D scores that should be considered. For example, treatment with antidepressant medication has been shown to result in salutary personality change (i.e., decreased neuroticism) compared to cognitive therapy or placebo (66).

Future Directions: Developing Strategies for Maximizing and Minimizing Placebo Response in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

Valid evaluation of putative antidepressant agents requires that placebo response be minimized in the drug development setting, while the best care for patients with depression may involve maximizing placebo response in clinical treatments. Data presented in this review suggest that the next generation of research aimed at reducing placebo response should focus on limiting patient expectancy and the intensity of therapeutic contact in antidepressant clinical trials (see Table 2). More research is needed to elucidate how antidepressant study design, the content and process of informed consent discussions, and clinician attitudes affect patient expectancy and treatment outcome. Designs in which patients have a higher probability of receiving placebo (i.e., 50%) may be preferable to designs randomizing patients to multiple active treatment arms and placebo. In terms of therapeutic contact intensity, future studies should examine whether clinical trials could be made more efficient and generalizable to clinical practice by reducing the amount of contact with health care staff to levels resembling treatment in the community. However, it must be determined whether acceptable attrition rates and patient safety can be maintained while reducing placebo response.

Table 2.

Study Design Features Influencing Placebo Response in Antidepressant Clinical Trials.

| Increase placebo response | Decrease placebo response | Strength of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| More study sites | Fewer study sites | Strong |

| Poor rater blinding | Good rater blinding with blind assessment | Strong |

| Multiple active treatment arms | Single active treatment arm | Strong |

| Lower probability of receiving placebo | Higher probability of receiving placebo | Strong |

| Single baseline rating | Multiple baseline ratings | Medium |

| Briefer duration of illness in current episode | Longer duration of illness in current episode | Medium |

| More study visits | Fewer study visits | Medium |

| Sample of symptomatic volunteers | Sample of self-referred patients | Weak |

| Optimistic/enthusiastic clinicians | Pessimistic/neutral clinicians | Weak |

Conversely, the optimal strategy in clinical practice may be to combine active medication with a presentation and level of therapeutic contact that enhances placebo effects, leading to greater medication response. Updated clinical management techniques may involve educating patients about the effectiveness of the prescribed medication and utilizing a confident and enthusiastic interpersonal style. While efforts to identify the “elusive placebo reactor” have historically been unsuccessful, it is possible that demographic or clinical characteristics related to the formulation of treatment expectancies or patients’ experience of the treatment setting may be associated with placebo response. Identifying patients likely to respond to these factors may permit them to be targeted with enhanced interventions. In developing these interventions, it may be useful to employ more “objective” measures of treatment response such as neuroimaging in order to ensure these interventions actually improve depression rather than simply introduce response biases.

A limitation of this review is that there is not sufficient space to address the neurobiology of placebo effects. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of expectancy-based placebo effects have provided converging evidence suggesting that the brain areas associated with generating and maintaining expectancies comprise prefrontal cortex subregions, orbitofrontal cortex, and the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (67). In treatment for depression, response to placebo has been associated with regionally-specific alterations in brain metabolism that represent a sub-set of the areas associated with response to antidepressant medication (68). Research aimed at further elucidating the biological pathways that lead to placebo effects is underway, and results of these studies are likely to yield information about the pathophysiology of Major Depressive Disorder and the mechanisms of action of antidepressant treatments.

In summary, placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials is a fascinating and complex phenomenon worthy of scientific investigation. Investigating the mechanisms of placebo effects has the potential to illuminate the pathophysiology of depression as well as the active ingredients of clinical trials. The public health benefit of research on placebo effects is that knowledge of their mechanisms may permit the development of strategies to modulate their magnitude depending on the context, thereby improving signal detection in drug development studies and increasing antidepressant response in clinical treatment.

Figure 2.

Response rates to antidepressant medication in placebo-controlled and comparator study designs for children and adolescents, adults, and older adults.

Table 1.

Sources of placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials.

| Factor | Contributes to placebo response | Influences pathophysiology of MDD | Susceptible to modification |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Measurement Factors | + | − | + |

|

| |||

| Natural History Factors | + | +/− | − |

|

| |||

| Treatment Factors | |||

| Expectancy-based placebo effects | + | + | + |

| Therapeutic Setting | + | + | + |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants K23 MH085236 (BRR) and T32 MH015144 (SPR), a Hope for Depression Research Foundation grant (BRR), and a NARSAD Young Investigator Award (BRR).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Rutherford has no disclosures to report, and Dr. Roose has served as a consultant to Pfizer and Forest Laboratories. This paper has not been previously presented.

Contributor Information

Bret R Rutherford, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Drive, Box 98, New York, NY 10032, 212 543 5746 (telephone), 212 543 6100 (fax).

Steven P. Roose, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

References

- 1.Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M. Placebo Response in Studies of Major Depression: Variable, Substantial, and Growing. JAMA. 2002;287:1840–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridge JA, Birmaher B, Iyengar S, Barbe RP, Brent DA. Placebo Response in Randomized Controlled Trials of Antidepressants for Pediatric Major Depressive Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:42–49. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan A, Bhat A, Kolts R, Thase ME, Brown W. Why has the Antidepressant-Placebo Difference in Antidepressant Clinical Trials Diminished over the Past Three Decades? CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2010;16:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan A, Khan S, Brown WA. Are placebo controls necessary to test new antidepressants and anxiolytics? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5:193–197. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702002912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooper M, Amsterdam JD. Do clinical trials reflect drug potential? A review of FDA evaluation of new antidepressants. 39th Annual NCDEU Meeting; Boca Raton. June 11–14, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nutt D, Goodwin G. ECNP Summit on the future of CNS drug research in Europe 2011: Report prepared for ECNP by David Nutt and Guy Goodwin. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2011;21:495–499. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cressey D. Psychopharmacology in crisis. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/news.2011.367.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2004: Changing History, Annex Table 3: Burden of disease in DALYs by cause, sex, and mortality stratum in WHO regions, estimates for 2002. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, Niederehe G, Thase ME, Lavori PW, Lebowitz BD, McGrath PJ, Rosenbaum JF, Sackeim HA, Kupfer DJ, Luther J, Fava M. Acute and Longer-Term Outcomes in Depressed Outpatients Requiring One or Several Treatment Steps: A STAR*D Report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirsch I, Sapirstein G. Listening to prozac but hearing placebo: A meta-analysis of antidepressant medication. Prev Treat. 1998 posted at http://journals.apa.org/prevention/volumeI/pre0010002a.html.

- 11.Khan A, Redding N, Brown WA. The persistence of the placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2008:791–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart-Williams S, Podd J. The placebo effect: dissolving the expectancy versus conditioning debate. Psychol Bull. 2004;30:324–340. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan A, Kolts RL, Thase ME, Krishnan RR, Brown W. Research Design Features and Patient Characteristics Associated with the Outcome of Antidepressant Clinical Trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2045–2049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutherford BR, Sneed JR, Roose SP. Does Study Design Affect Outcome? The Effects of Placebo Control and Treatment Duration in Antidepressant Trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:172–181. doi: 10.1159/000209348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sneed JR, Rutherford BR, Rindskopf D, Roose SP. Design Makes a Difference: A Meta-Analysis of Antidepressant Response Rates in Placebo-Controlled versus Comparator Trials in Late-Life Depression. Am J Geri Psychiatry. 2008;16:65–73. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181256b1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papakostas GI, Fava M. Does the probability of receiving placebo influence clinical trial outcome? A meta-regression of double-blind, randomized clinical trials in MDD. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2009;19:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinyor M, Levitt AJ, Cheung AH, Schaffer A, Kiss A, Dowlati Y, Lanctot KL. Does Inclusion of a Placebo Arm Influence Response to Active Antidepressant Treatment in Randomized Controlled Trials? Results from Pooled and Meta-Analyses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:270–279. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04516blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer B, Pilkonis PA, Krupnick JL, Egan MK, Simmens SJ, Sotsky SM. Treatment Expectancies, Patient Alliance, and Outcome: Further Analyses from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:1051–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krell HV, Leuchter AF, Morgan M, Cook IA, Abrams M. Subject Expectations of Treatment Effectiveness and Outcome of Treatment with an Experimental Antidepressant. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1174–1179. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutherford BR, Marcus S, Sneed JR, Devanand DP, Roose SP. Expectancy Effects in the Treatment of Depression: A Pilot Study. poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutherford BR, Sneed JR, Tandler J, Peterson BS, Roose SP. Deconstructing Pediatric Depression Trials: An Analysis of the Effects of Expectancy and Therapeutic Contact. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Blazi Z, Kleijnen J. Context effects. Powerful therapies or methodological bias? Eval Health Prof. 2003;26:166–79. doi: 10.1177/0163278703026002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bass MJ, Buck C, Turner L, Dickie G, Pratt G, Robinson HC. The physician’s actions and the outcome of illness in family practice. J Fam Pract. 1986;23:43–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benedetti F. Mechanisms of Placebo and Placebo-Related Effects Across Diseases and Treatments. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:33–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. Therapeutic effect of follow-up assessments on antidepressant and placebo response rates in antidepressant efficacy trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:287–292. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.028555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National Patterns in Antidepressant Treatment by Psychiatrists and General Medical Providers: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1064–1074. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stettin GD, Yao J, Verbrugge RR, Aubert RE. Frequency of follow-up care for adult and pediatric patients during initiation of antidepressant therapy. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:453–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrato EH, Libby AM, Orton HD, de Gruy FV, Brent DA, Allen R, Valuck RJ. Frequency of Provider Contact after FDA Advisory on Risk of Pediatric Suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:42–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein DJ, Baldwin DS, Dolberg OT, Despiegel N, Bandelow B. Which factors predict placebo response in anxiety disorders and major depression? An analysis of placebo controlled studies of escitalopram. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1741–1746. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trivedi M, Rush J. Does a Placebo Run-In or a Placebo Treatment Cell Affect the Efficacy of Antidepressant Medications? Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;11:33–43. doi: 10.1038/npp.1994.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faries DE, Heiligenstein JH, Tollefson GD, Potter WZ. The double-blind variable placebo lead-in period: results from two antidepressant clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:561–568. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:215–220. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcus SM, Gorman JM, Tu X. Rater bias in a blinded randomized placebo-controlled psychiatry trial. Stat Med. 2006;25:2762–2770. doi: 10.1002/sim.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rief W, Nestoriuc Y, Weiss S, Welzel E, Barsky AJ, Hofmann SG. Meta-analysis of the placebo response in antidepressant trials. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert MJ, Hatch DR, Kingston MD. Zung, Beck, and the Hamilton rating scales as measures of treatment outcome: a meta-analytic comparison. J Clin Consult Psych. 1986;54:54–59. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landin R, DeBrtoa DJ, DeVries TA, Potter WZ, Demitrack The Impact of restrictive Entry Criterion During the Placebo Lead-In Period. Biometrics. 2000;56:271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Katzelnik DJ, DeBrota DJ, Chappell PB, Modell JG. Is It Easier to Find What You Are Looking for if You Think You Know What It Looks Like? J Clin Psychopharm. 2007;27:121–125. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3180387820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenberg RP, Bornstein RF, Greenberg MD, Fisher S. A meta-analysis of antidepressant outcome under “blinder” conditions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:664–669. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeBrota DJ, Demitrack MA, Landin R, Kobak KA, Greist JH, Potter W. A comparison between interactive voice response system–administered HAM-D and clinician-administered HAM-D in patients with major depressive episode. Paper presented at: 39th Annual Meeting, New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; June 1–4, 1999; Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paulhus DL. Measurement and Control of Response Bias. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc; 1991. pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulsant BH, Kastango KB, Rosen J, Stone RA, Mazumdar S, Pollock BG. Interrater Reliability in Clinical Trials of Depressive Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 Sep 1;159:1598–1600. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobak KA, Kane JM, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA. Why do clinical trials fail? The problem of measurement error in clinical trials: time to test new paradigms? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:1–5. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31802eb4b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Coryell WH, Endicott J, Taylor J. Long-term outcome of episodes of major depression. JAMA. 1984;252:788–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rutherford BR, Mori S, Sneed JR, Pimontel MA, Roose SP. Contribution of Spontaneous Improvement to Placebo Response in Depression: A Meta-Analytic Review. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brody B, Leon AC, Kocsis JH. Antidepressant Clinical Trials and Subject Recruitment: Just Who Are Symptomatic Volunteers? Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1245–1247. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11060864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kisely S, Scott A, Denney J, Simon G. Duration of untreated symptoms in common mental disorders: association with outcome. Br J Psych. 2006;189:79–80. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.019869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benedetti F, Arduino C, Costa S. Loss of expectation-related mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease makes analgesic therapies less effective. Pain. 2006;121:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liberman RP. The elusive placebo reactor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1967;5:557–566. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shapiro AK, Morris LA. The placebo effect in medical and psychological therapies. In: Garfield SL, Bergins AE, editors. Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change: an empirical analysis. New York: Aldine Publishing; 1978. pp. 477–536. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doongaji DR, Vahia VN, Bharucha MP. On placebos, placebo responses and placebo responders. A review of psychological, psychopharmacological and psychophysiological factors. J Postgrad Med. 1978;24:147–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J. Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity: A Patient-Level Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB. Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5:260–268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glassman AH, Roose SP. Delusional depression: a distinct clinical entity? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:424–427. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290058006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Koszycki D, Laliberte MA, van Zyi LT, Baker B, Swenson JR, Ghatavi K, Abramson BL, Dorian P, Guertin MC. Effects of Citalopram and Interpersonal Psychotherapy on Depression in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. The Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) Trial. JAMA. 2007;297:367–379. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roose SP, Sackeim HA, Krishnan KRR, Pollock BG, Alexopoulos G, Lavretsky H, Katz IR, Hakkarainen H. Antidepressant Pharmacotherapy in the Treatment of Depression in the Very Old: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2050–2059. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kirsch I. Are Drug and Placebo Effects in Depression Additive? Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:733–735. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00832-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirsch I. Changing Expectations: A Key to Effective Psychotherapy. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muthen B, Brown HC. Estimating drug effects in the presence of placebo response: Causal inference using growth mixture modeling. Statist Med. 2009;28:3363–3385. doi: 10.1002/sim.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.“Treating Depression: Is There a Placebo Effect?” 60 Minutes. CBS Broadcasting, Inc; Feb 19, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gueorguieva R, Mallincrodt C, Krystal JH. Trajectories of Depression Severity in Clinical Trials of Duloxetine: Insights into Antidepressant and Placebo Responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1227–1237. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thase ME, Larsen KG, Kennedy SH. Assessing the ‘true’ effect of active antidepressant therapy v. placebo in major depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:501–507. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Depression: The treatment and management of depression in adults. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; London: 2009. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lave JR, Frank RG, Schulberg HC, Kamlet MS. Cost-Effectiveness of Treatments for Major Depression in Primary Care Practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:645–651. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Domino ME, Foster EM, Vitello B, Kratochvil CJ, Burns BJ, Silva SG, Reinecke MA, March JS. Relative cost-effectiveness of treatments for adolescent depression: 36–week results from the TADS randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:711–720. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a2b319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barlow DH. Negative effects from psychological treatments. Amer Psychologist. 2010;65:13–19. doi: 10.1037/a0015643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam J, Shelton R, Schalet B. Personality Change During Depression Treatment: A Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1322–1330. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Petrovic P, Dietrich T, Fransson P, Andersson J, Carlsson K, Ingvar M. Placebo in Emotional Processing—Induced Expectations of Anxiety Relief Activate a Generalized Modulatory Network. Neuron. 2005;46:957–969. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mayberg HS, Silva JA, Brannan SK, Tekell JL, Mahurin RK, McGinnis S, Jerebek PA. The functional neuroanatomy of the placebo effect. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:728–737. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]