Abstract

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Bdf1p associates with the basal transcription complexes TFIID and acts as a transcriptional regulator. Lack of Bdf1p is salt sensitive and displays abnormal mitochondrial function. The nucleotidase Hal2p detoxifies the toxic compound 3′ -phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate (pAp), which blocks the biosynthesis of methionine. Hal2p is also a target of high concentration of Na+. Here, we reported that HAL2 overexpression recovered the salt stress sensitivity of bdf1Δ. Further evidence demonstrated that HAL2 expression was regulated indirectly by Bdf1p. The salt stress response mechanisms mediated by Bdf1p and Hal2p were different. Unlike hal2Δ, high Na+ or Li+ stress did not cause pAp accumulation in bdf1Δ and methionine supplementation did not recover its salt sensitivity. HAL2 overexpression in bdf1Δ reduced ROS level and improved mitochondrial function, but not respiration. Further analyses suggested that autophagy was apparently defective in bdf1Δ, and autophagy stimulated by Hal2p may play an important role in recovering mitochondrial functions and Na+ sensitivity of bdf1Δ. Our findings shed new light towards our understanding about the molecular mechanism of Bdf1p-involved salt stress response in budding yeast.

Introduction

Like many other organisms, the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae possesses multiple mechanisms to adapt to various environmental stresses. When yeast encounters salt stress, for instance, the plasma membrane Na+-ATPase, encoded by ENA1/PMR2, pumps excess Na+ to outside of the cell [1]. Other pathways, like HOG-MAPK pathway and calcineurin signaling pathway may also be activated by salt stress [2]. In addition, many other genes, including NHA1 (encoding a Na+/H+ antiporter located at the plasma membrane), TRK1/TRK2 (encoding K+ transporters located at the plasma membrane), and NHX1 (encoding a Na+/H+ antiporter localized in the cytoplasm), also participate in salt stress response in yeast [3], [4].

Bromodomain Factor 1 (Bdf1p) belongs to the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family, a novel group of transcriptional regulators [5]–[8]. Bdf1p contains two copies of the bromodomain, which binds to the acetylated lysine residue(s) of histone H3 or H4 [9]–[11]. It also contains one copy of the extra-terminal (ET) domain, which can be phosphorylated by casein kinase 2 (CK-2) [7]–[8]. Bdf1p associates with the basal transcription complexes TFIID and corresponds to the carboxyl-terminal region of TAFII250 [12]. Bdf1p is also a member of the SWR1 complex, which is required for recruitment of histone H2A variant htz1 onto chromatin [13].

Previous studies have shown that BDF1 plays a role in multiple stresses, including salt, high temperature, caffeine and LiCl [14]. Our previous data demonstrate that BDF1 deletion causes mitochondria dysfunction and apoptosis under salt stress; and the Bdf1p-involved salt stress response is independent of Ena1p, Trk1p, MAPK pathway and calcineurin signaling pathway [15]. However, the molecular mechanism of Bdf1p-involved salt stress response remains unclear.

HAL2 (also named as MET22) encodes a bisphosphate-3′-nucleotidase, which converts toxic 3′ -phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate (pAp), the intermediate product of the sulfate assimilation pathway, into nontoxic AMP and Pi. Hal2p is inhibited by high concentration of Na+ or Li+, leading to pAp accumulation [16]. The accumulated pAp then inhibits the 5′-3′-exoribonuclease activity and blocks the biosynthesis of methionine [17]–[19].

In this study, we revealed that overexpression of HAL2 increased the salt resistance of bdf1Δ. We further demonstrated HAL2 expression was regulated by Bdf1p. Further analysis suggests that Hal2p may enhance bdf1Δ salt resistance by stimulating autophagy, which removes harmful substances, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) in bdf1Δ.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Strains Construction

All plasmids and the S. cerevisiae strains used in this study were listed in Table 1. HAL2 or BDF1 ORF was cloned into a 2-µm plasmid pYX242, resulting in pYX242-HAL2 or pYX242-BDF1, respectively. GFP-ATG8 was cloned into plasmid pRS316 [20], named pRS316-GFP-ATG8. The plasmids were transformed into different strains as described in the results section. The DNA fragments of the disruption cassettes for the target genes were amplified by four primers [21] and transformed into W303-1A or bdf1Δ [15], producing different deletion strains. The deletion strains were verified by PCR. The primers used for PCR amplification were listed in Table S1. BDF1-Flag strain was constructed as previously described [22].

Table 1. Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains | Genotype/Properties | Reference/Resource |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae W303 | MATa, leu2-3/112 ura3-1 trp1-1 his3-11/15 ade2-1 can1-100 | [14] |

| bdf1Δ | Derivative of W303: BDF1::kanMX4 | This study |

| W303+pYX242 | W303 transformed with empty pYX242 | This study |

| bdf1Δ+pYX242 | bdf1Δ transformed with empty pYX242 | This study |

| bdf1Δ+HAL2 | bdf1Δ transformed with pYX242-HAL2 | This study |

| bdf1Δ+BDF1 | bdf1Δ transformed with pYX242-BDF1 | This study |

| W303+HAL2 | W303-1A transformed with pYX242-HAL2 | This study |

| ena1Δ | Derivative of W303-1A: ENA1::HIS3 | [32] |

| hal2Δ | Derivative of W303-1A: HAL2::URA3 | This study |

| bdf1Δhal2Δ | Derivative of bdf1Δ: HAL2::URA3 | This study |

| BDF1-Flag | Derivative of W303-1A: BDF1::BDF1–Flag | Deposited in our lab |

| plasmids | ||

| pRS316-GFP-ATG8 | GFP-ATG8 fusion segments cloned to pRS316 | This study |

| pRS315-GFP-ATG8 | GFP-ATG8 fusion segments cloned to pRS315 | This study |

| pYX242+BDF1 | BDF1 ORF segments cloned to pYX242 | This study |

| pYX242+HAL2 | HAL2 ORF segments cloned to pYX242 | This study |

Spot dilution growth assay

The growth phenotype of the strains was analyzed by spot assay as previously described [23]. Briefly, cells were cultured overnight either in YPD media (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) or in complete synthetic defined (SD) medium (0.17% yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% (NH4)2SO4, 2% glucose, and supplemented with arginine, histidine, tryptophan, uracil, adenine and leucine). Cells were then harvested by centrifugation. Cells were washed twice and resuspended in ddH2O. The cell density was normalized to an OD600 = 1.0. Four µl of each ten-fold serial dilution of the cultures were spotted onto appropriate solid medium. Growth was monitored after 3 days at 30°C.

Na+ or Li+ treatment

The overnight cultures were inoculated in 100 ml fresh medium and then grown to mid-log phase at 30°C. Half of the culture was transferred to media containing final concentration of 0.5 mol.L−1 NaCl or 0.1 mol.L−1 LiCl. Cells were grown at 30°C for 45 min for most of the experiments, except for concentration detection of Na+ (5 h) or pAp (4 h with NaCl or 2 h with LiCl). Samples without salt treatment were used as controls in all cases.

Determination of Na+ and pAp concentration

To detect the intracellular Na+ concentration, cells were washed four times with 20 mmol.L−1 MgCl2. The air-dried cells were nitrified in a nitrification tube with 3 ml nitric acid for 1 hour at room temperature. Five ml of ultra-pure water was then added to the nitrified cells and incubated in a Microwave Digestion System (Milestone) for 45 min at 120°C. The Na+ concentration in the nitrified cells was analyzed by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (SOLAAR) at 589 nm with air-acetylene flame and 1.1 L.min−1 gas flows [6], [24], [25].

To detect the intracellular pAp concentration, salt-treated cells were harvested and extracted with 1 ml of 2 mol.L−1 perchloric acid in a ice-bath for 15 min. Extracts were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min. 900 µl supernatant was adjusted to pH 6.0. After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered by filter membrane for HPLC analysis. Yeast nucleotide extraction and HPLC analysis were conducted as described previously [26]. 10 µl of each extract were analyzed by HPLC (SHIMADZU). Samples were applied to a reversed phase C18 column (5-µm particle size, GL Sciences), eluted and detected as described previously [26]. Nucleotide peaks were identified by co-injection with standards (AMP, ADP, ATP and pAp from Sigma).

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The treated cells were rapidly frozen by liquid nitrogen. Total yeast RNA was isolated using UNIQ-10 spin column RNA purification kits (BBI) in accordance with the manufacturer's instruction. Total RNA was treated with DNase I (Takara) to eliminate genomic DNA. 2 µg of DNA-free total RNA was used to synthesize the first strand of cDNA in 20 µl reverse transcription (RT).One µl of RT reaction product was used for qPCR using the LightCycle PCR System (Bio-Rad) and SYBR Green I monitoring method. The forward and reverse specific primers were listed in Table S1. The ACT1 gene was used as a reference for normalization. Fold changes in gene expression were calculated using the comparative 2−ΔΔt method [5].

Western blot

Protein sample preparation, SDS-PAGE and Western blots were performed as described previously [27]. Primary antibodies were polyclonal rabbit anti-yeast Hal2p, anti-β-tubulin (ANBO) and anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (ZSGB, ZB2301).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP was accomplished using ENZ ChIP kits (MILLIPORE) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Yeast cell wall was removed by zymolase as described previously [28]. Immunoprecipitation was performed with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-Flag (sc-807; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Primers used in ChIP amplifications were listed in Table S1.

Assessment of ROS, mitochondrial membrane potential (Δφ) and GFP-ATG8

Detection of ROS and assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δφ) were performed as described previously [15], [29]. The values of ROS, Δφ and GFP-ATG8 fluorescence were quantified as the relative fluorescence intensity using ImageJ software. Photographs were representatives of three independent experiments.

Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Nikon ECLIPSE 80i system equipped with a plan Apochromat 40× objective (NA = 0.95) and a plan Apochromat 60× oil objective (NA = 1.40). Images were acquired and analyzed using NIS-Elements AR 3.1 software.

Statistical Analysis of Data

A two-tailed t test, assuming equal variances, was used to determine whether the differences between the strains' behavior were statistically significant.

Results

1. The high sensitivity of bdf1Δ to salt stress was not caused by intracellular Na+ accumulation

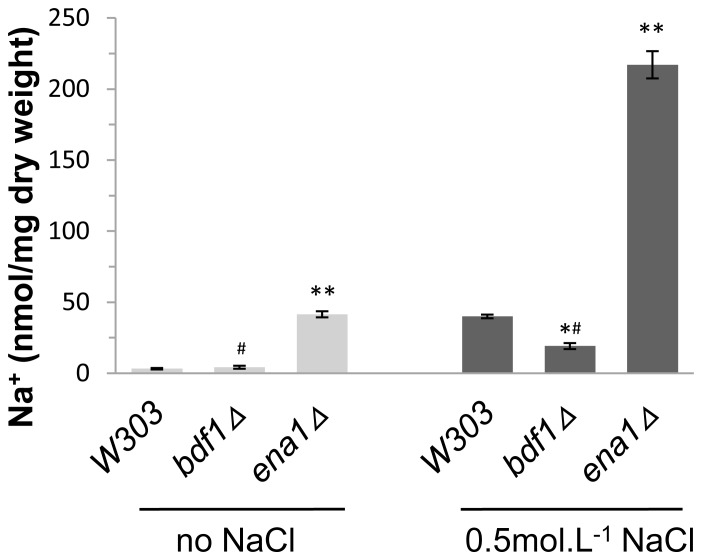

High Na+ concentration is one of the factors for toxicity of salt stress [4]. We asked if the salt sensitivity of bdf1Δ is due to Na+ toxicity. The intracellular Na+ concentration was detected by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. ENA1, which encodes a Na+-ATPase that pumps the excess intracellular Na+ out of the cells [30], [31], was used as a positive control. When cells were treated with NaCl, the Na+ concentration in ena1Δ was higher (p<0.01) than that in wild type (Fig. 1). It was also higher (p<0.01) than that in bdf1Δ either in the presence or absence of NaCl. Since both the bdf1Δ and ena1Δ mutants were sensitive to 0.5 mol.L−1 NaCl [15], these results suggested that the salt sensitivity of bdf1Δ was not caused by high intracellular Na+ concentration.

Figure 1. The intracellular Na+ concentration in bdf1Δ was lower than that in wild type.

Mid-log phase cells were grown for 5 h with or without 0.5 mol.L−1 NaCl. The treated cells were washed with MgCl2 and air dried. The dried cells were nitrified with nitric acid. The Na+ concentration was analyzed by atomic absorption spectrophotometry at 589 nm. Error bars denote standard deviation (SD). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. wild type under the same treatment, # P<0.01 vs. ena1Δ under the same treatment, n = 3.

2. HAL2 overexpression in bdf1Δ increased salt stress resistance and bdf1ΔHal2Δ double deletion strain was more sensitive to salt stress

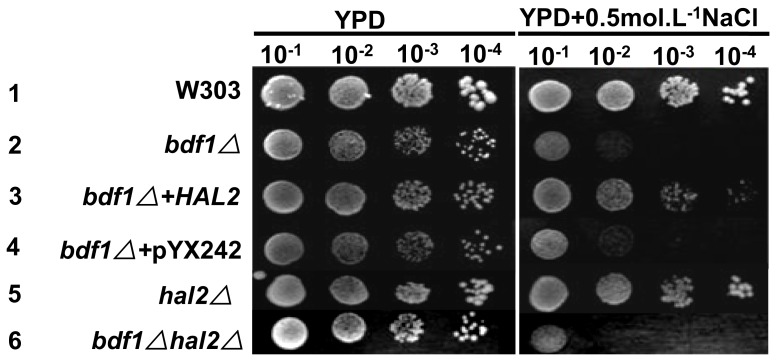

The nucleotidase Hal2p is a detoxifying enzyme and a target of high concentration of Na+, which competitively replaces Mg2+ in the active core of Hal2p [32]. To confirm whether Hal2p affects the salt sensitivity of BDF1 deletion, Hal2 deletion and HAL2 overexpression strains were constructed (Table 1). Overexpression of HAL2 in bdf1Δ significantly increased the resistance to salt stress (Fig. 2, line 3). HAL2 deletion alone had no significant effect on salt sensitivity in YPD medium (Fig. 2, line 5). The bdf1ΔHal2Δ double deletion, however, was more sensitive to Na+ stress (Fig. 2, line 6) than bdf1Δ single deletion. This result suggests salt sensitivity of the bdf1Δ can be ameliorated by overexpression of HAL2 and the BDF1- and HAL2-involved salt stress responses may be different.

Figure 2. Overexpression of HAL2 in bdf1Δ recovered its resistance to NaCl.

5 µl aliquots of 10-fold serial dilutions of the mid-log phase cultures were spotted onto YPD plates and incubated at 30°C for 3 d.

3. Deletion of BDF1 reduced the expression level of HAL2

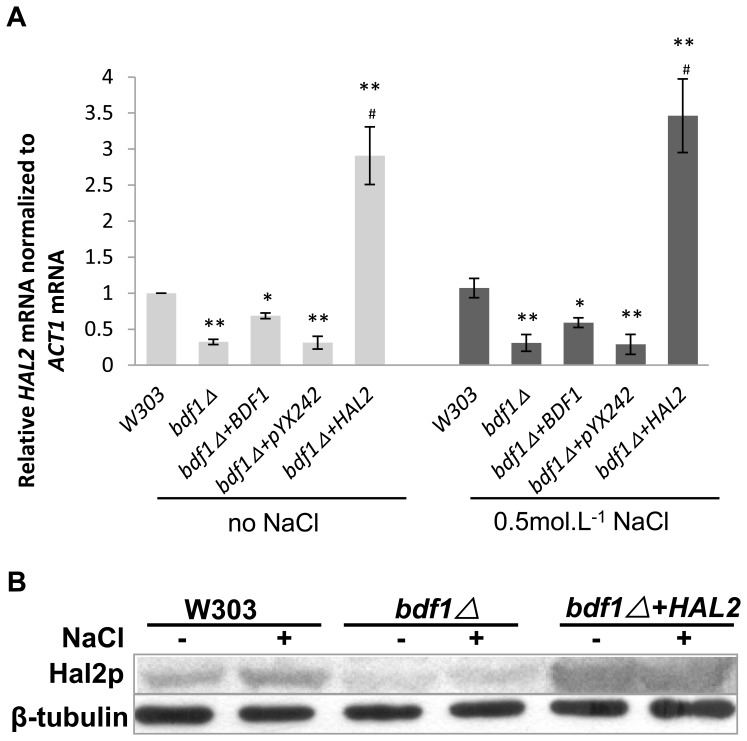

To confirm if HAL2 is involved in the bdf1Δ-induced salt sensitivity,the expression level of HAL2 was detected by RT-qPCR. As shown in Fig. 3A, the HAL2 mRNA level in the bdf1Δ mutant was about two folds lower than that in wild type (p<0.01). No significant changes in HAL2 mRNA levels were observed in the bdf1Δ strain between cells with and without NaCl (0.5 mol.L−1) treatment. When BDF1 was reintroduced into bdf1Δ strain using a 2 µ plasmid, HAL2 mRNA level was partially recovered, suggesting that BDF1 affects the HAL2 expression (Fig. 3A). Spot assay showed that bdf1Δ+BDF1 is less resistant to salt stress than the wild type (Fig. S1), suggesting that the expression level of the 2 µ plasmid encoded BDF1 is less than the endogenous BDF1. This is most likely the reason that the HAL2 mRNA level was only partially recovered in bdf1Δ+BDF1. The HAL2 mRNA level in bdf1Δ+HAL2 was about 9 folds higher than that in bdf1Δ (p<0.01) when cells were treated with or without NaCl. A similar pattern was observed at protein level by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B). After BDF1 was deleted, HAL2 protein level was reduced to ∼30% of that in wild type (p<0.01). The HAL2 protein level in bdf1Δ+HAL2 was about 9 folds higher than that in bdf1Δ. This indicated BDF1 could affect the HAL2 expression at mRNA level and protein level.

Figure 3. Deletion of BDF1 reduced HAL2 expression at both mRNA and protein levels.

The mid-log phase cultures in YPD at 30°C were incubated for 45 min with or without 0.5 mol.L−1 NaCl. (A) Relative fold-changes of HAL2 mRNA were calculated against the wild type without NaCl treatment. Error bars denote standard deviation (SD). **P<0.01 vs. wild type under the same treatment, # P<0.01 vs. bdf1Δ under the same treatment, n = 3. (B) The Hal2p protein level was analyzed with whole cell protein by Western blot. β-tubulin was used as control. The polyclonal Hal2p antibody and anti-β-tubulin antisera were used in Western blot analysis.

4. Bdf1p does not regulate HAL2 expression directly

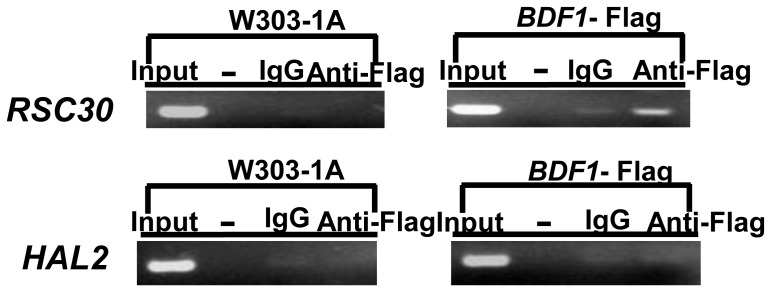

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was used to detect how HAL2 expression is regulated by Bdf1p. The promoter regions probed by ChIP correspond to nucleotides −200 to −1 relative to the translation start sites and these regions were used for PCR detection. The promoter of RSC30, which is directly bound by Bdf1p [33], was used as a positive control. Fig. 4 showed that the promoter region of RSC30 but not HAL2 was detected in Bdf1p immunoprecipitation. This result, together with that of HAL2 expression (Fig. 3), suggests that the HAL2 expression is positively regulated by Bdf1p but in an indirect manner. We speculate that other transcription factor(s) are involved to mediate the interaction between Bdf1p and HAL2 expression.

Figure 4. Bdf1p regulated HAL2 expression indirectly.

The anti-Flag antibody was used for Bdf1p precipitation and IgG was used as a negative control. The promoter regions probed by ChIP correspond to nucleotides −200 to −1. Error bars denote standard deviation (SD). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. wild type under the same treatment, n = 3.

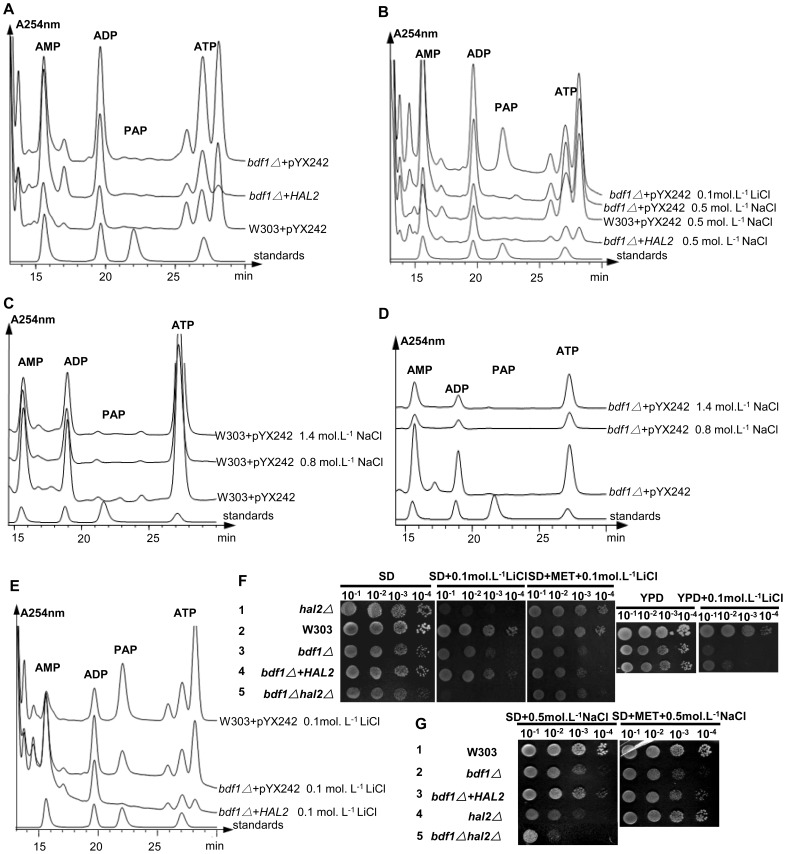

5. Salt sensitivity of bdf1Δ was not due to high level of intracellular pAp or the lack of methionine

Hal2p, a detoxifying enzyme, converts toxic 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate (pAp) into nontoxic AMP and Pi in the process of sulfate assimilation to methionine [34]. Methionine supplementation or HAL2 overexpression could improve salt tolerance [32]. Although there was no Na+ accumulation in bdf1Δ strain (Fig. 1), BDF1 deletion caused a decreased level of HAL2 expression (Fig. 3A). To see if the salt sensitivity of bdf1Δ is caused by pAp accumulation the intracellular pAp concentrations was measured by HPLC. Unlike the RS-16 strain of S cerevisiae, in which pAp accumulation was detectable when treated with NaCl (0.6 mol.L−1 or higher) [16], [34], no pAp was detected in wild type (W303 background) or its derived stains either without (Fig. 5A) or with (Fig. 5B) NaCl treatment, even when NaCl concentration was increased to 1.4 mol.L−1 (Fig. 5C, D). However, when cells were treated with 0.1 mol.L−1 of LiCl, accumulation of pAp was detected in wild type as previously reported [35] as well as in bdf1Δ (Fig. 5E). Overexpression of HAL2 diminished the pAp accumulation in bdf1Δ (Fig. 5E). Spot assay showed that overexpression of HAL2 in bdf1Δ partially suppressed the sensitivity to Li+ or Na+ in both YPD and SD media (Fig. 2, Lines 2 and 3 and Figs. 5F, lines 3 and 4, 5G, Lines 2 and 3). As reported previously [32], addition of methionine (20 mg.L−1) recovered the Na+ and Li+ resistance of hal2Δ. Addition of methionine did not, however, recover the salt sensitivity of bdf1Δ (Figs. 5F, lines 1 and 3, 5G, Lines 1 and 3). These results suggest that the high level of Hal2p was required for increasing the resistance of bdf1Δ to both sodium and lithium salt stress. It also suggests that the sensitivity of bdf1Δ to Na+ or Li+ stress was not due to the accumulation of pAp or lack of methionine.

Figure 5. Salt sensitivity of bdf1Δ was not due to intracellular pAp or the lack of methionine.

Cells grown to OD600 = 0.2∼0.4 in SD medium were incubated at 30°C without or with different concentrations of NaCl for 4 h, or 0.1 mol.L−1 LiCl for 2 h. The intracellular pAp concentration was determined as described in Materials and Methods (A–E). 5 ul aliquots of 10-fold serial dilutions of the mid-log phase cultures were spotted onto plates and incubated at 30°C for 3 d (F, G).

In addition to its detoxifying function, Hal2p is involved in amino acid metabolism [34]. The hal2Δ exhibited Na+ sensitivity on medium lacking amino acids app:ds:lack(Fig. 5G, Line 4) but not on medium rich in amino acids (Fig. 2, Line 5). Meanwhile, bdf1Δhal2Δ double mutant showed enhanced sensitivity to Na+ compared to either single mutant (Fig. 5G, Lines 2, 4, 5 and Fig. S2). These results suggest that the pathway of Bdf1p-involved Na+ stress response could be different from that of Hal2p. This notion is supported by the fact that amino acids can rescue the salt stress of hal2 but not bdf1 mutants.

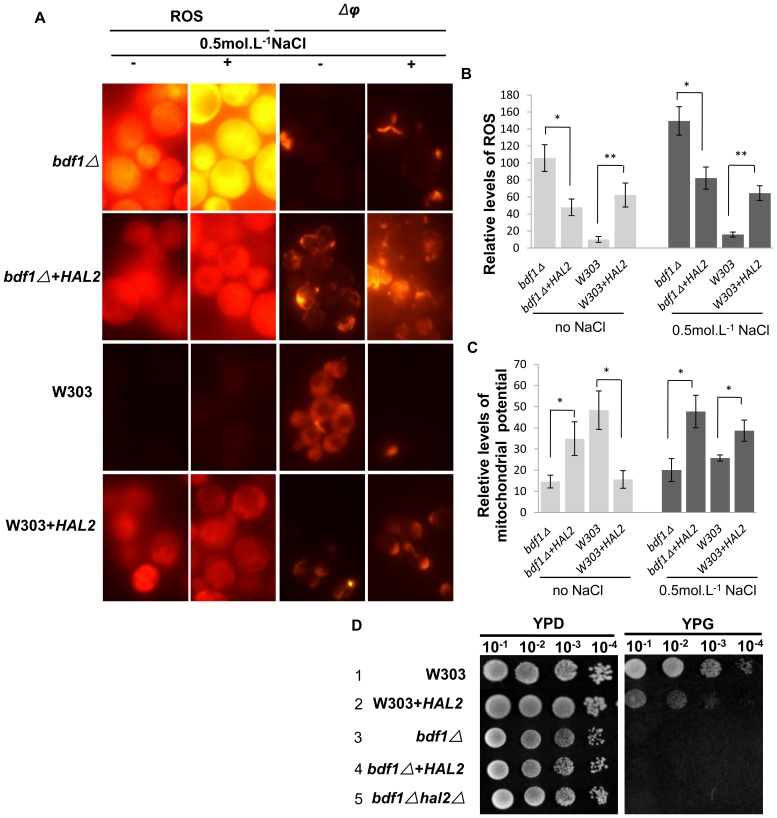

6. HAL2 overexpression reduced ROS accumulation and partially recovered mitochondrial function of bdf1Δ

It has been observed that salt stress in bdf1Δ caused an increase of ROS and decrease of Δφ [14], both are markers of apoptotic cell death. The bdf1Δ grows slowly in nonfermentable carbon sources, such as glycerol, due to its mitochondrial respiratory deficiency [36].

Because overexpression of HAL2 enhanced the salt resistance of bdf1Δ (Fig. 2, Line 3, Fig. 5G, Line 3), ROS levels and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δφ) were measured [37], [38], to see if HAL2 overexpression causes any changes of ROS level and mitochondrial membrane potential.

Our result showed that overexpression of HAL2 in bdf1Δ reduced the ROS level both in the absence (0.55 fold) (p<0.05) and in the presence (0.45 fold) (p<0.05) of NaCl (Fig. 6A, B). It also enhanced the Δφ (1.39 folds without NaCl, p<0.05; or 1.38 folds with NaCl, p<0.05) (Fig. 6A, C). These results suggest that HAL2 was indeed involved in the removal of ROS and in augment of Δφ in bdf1Δ cells. Surprisingly, overexpression of HAL2 in wild type induced ROS production (5.20 folds without NaCl, p<0.01; or 3.08 folds with NaCl, p<0.01) (Fig. 6A, B). HAL2 overexpression also decreased mitochondrial membrane potential (Δφ) (0.67 fold without NaCl, p<0.05; or 0.50 fold with NaCl, p<0.05) (Fig. 6A, C). Unlike the wild type, bdf1Δ did not grow normally on glycerol medium (YPG) even with HAL2 overexpression (Fig. 6D, Lines 3, 4) and HAL2 over-expression caused the wild type to grow slower (Fig. 6D, Lines 1, 2), suggesting that Hal2p helped to reduce ROS accumulation and recover the mitochondrial function but not the respiratory deficiency in bdf1Δ. The excess amount of Hal2p in wild type may cause damage to cells.

Figure 6. HAL2 overexpression affected ROS accumulation and partially affected the mitochondrial function.

Mid-log phase cells were incubated for 45 min with or without 0.5 mol.L−1 NaCl. ROS were detected by dihydrorhodamine 123. Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured with JC-1 (A) The ROS (B) and Δφ (C) fluorescence values were quantified as the relative fluorescence intensity per strain by ImageJ software and averaged from ∼50 cells. Error bars denote standard deviation (SD). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. strains without HAL2 overexpression under the same treatment, n = 4. (D) 5 ul aliquots of 10-fold serial dilutions of the mid-log phage cultures were spotted onto YPG plates and incubated at 30°C for 3 d.

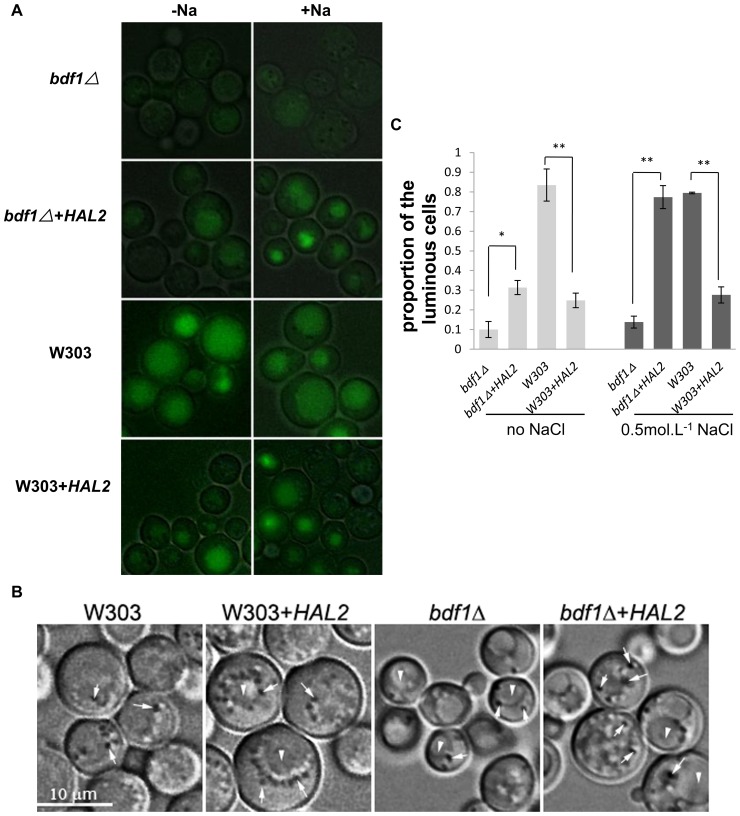

7. Autophagy was defective in bdf1Δ and stimulated by HAL2 overexpression

Autophagy is an intracellular catabolic process through autophagosomes to degrade the cytosolic components [39]–[41]. This process counteracts with internal and external stresses and alters the cell metabolic equilibrium [39]. We speculate that autophagy plays a role in the Hal2p involved ROS removal. To test this possibility, we tagged the Atg8p, which localizes on the inner membrane of autophagosome [42], [43], with GFP at its N-terminus (GFP-ATG8) as a marker to detect the autophagy level [43], [44]. The autophagosomes were also observed using a bright-field light microscope.

We first checked the autofluorescence background of strains with no GFP tag. All strains showed a similar but constant autofluorescence with or without NaCl treatment (data not shown). The GFP-ATG8 of bdf1Δ cells exhibited very weak GFP fluorescence regardless of NaCl treatment (Fig. 7A). Overexpression of HAL2 in bdf1Δ significantly increased the fluorescence intensity of GFP-ATG8. Proportion of cells with fluorescence was also increased (p<0.05) either with or without NaCl treatment (Fig. 7C). Overexpression of HAL2 in wild type also caused an increase in fluorescence intensity, either with or without NaCl treatment (Fig. 7A) although the proportion of cells with GFP fluorescence (Fig. 7C) reduced. This reduction could be due to cell death induced by autophagy. Overall, Na+ stress enhanced autophagy fluorescence in all the strains (Fig. 7A). We also observed more autophagosomes around the vacuoles in both bdf1Δ and wild type strains with HAL2 overexpression (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that HAL2 overexpression could stimulate autophagy.

Figure 7. BDF1 was required for autophagy and HAL2 stimulated autophagy.

Yeast cells of OD600>1.5 were collected from SC medium and incubated for 45 min with (+) or without (−) 0.5 mol.L−1 NaCl. (A) Cells were transformed with the pRS316-GFP-ATG8. The GFP-ATG8 fluorescence images were merged with bright field images to show the outlines of the cells. (B) The autophagosomes were observed by a bright-field light microscope. Arrows indicate autophagosomes; arrowheads indicate vacuoles. (C) Cells with fluorescence were measured from about 200 cells. Error bars denote standard deviation (SD). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. strains without HAL2 overexpression under the same treatment, n = 3.

Taken together, we believed that HAL2 overexpression reduced ROS accumulation and partially recovered the mitochondrial function in the bdf1Δ. In contrast, overexpression of HAL2 in wild type appeared to damage the respiration of mitochondria possibly by the excessive autophagy and recycling of cytoplasmic contents, such as mitochondria, into the vacuole. The excessive autophagy may cause stress itself, therefore, increasing the ROS level in wild type cells.

Discussion

1. Overexpression of HAL2 reduces saltsensitivity of bdf1Δ possibly via removal of ROS by HAL2-stimulated autophagy

High intracellular Na+ concentration is one of the most important factors to salt stress in yeast. Our data showed, however, that the concentrations of Na+ in wild type and bdf1Δ were similar and both were lower than that of ena1Δ (Fig. 1). Ena1p is the Na+-ATPase that pumps the excess intracellular Na+ out of the cells [30]. This indicates the sodium discharge pump is functional in bdf1Δ and Na+ toxicity is not the main reason of bdf1Δ salt sensitivity.

To investigate the possible reasons of bdf1Δ salt sensitivity, we identified several genes that can recover salt sensitivity of bdf1Δ, and HAL2 is one of them. Overexpression of HAL2 in bdf1Δ recovered its sensitivity to Na+ in both rich (Fig. 2, Line 3) and minimal media (Fig. 5G, Line 3).

We previously reported that the BDF1 deletion aggravated apoptosis under Na+ stress due to mitochondrial dysfunction [15]. Overexpression of HAL2 restrained bdf1Δ Na+ sensitivity (Fig. 2, Fig. 5G). Therefore, the mitochondria function index ROS and Δφ as well as cells growth on a non-fermentable carbon source were examined. Overexpression of HAL2 in bdf1Δ increased the Δφ and decreased the ROS level (Fig. 6). The opposite effect, however, occurred when HAL2 was overexpressed in wild type. Cells (W303+HAL2, Table 1) displayed ROS accumulation, Δφ decrease and growth decrease on glycerol containing medium (Fig. 6). These data indicate that HAL2 overexpression recovered part of the mitochondria functions in bdf1Δ mutant but may induce harmful effects in the wild type cells.

Comparison of GSH/GSSG ratio between WT+HAL2 and bdf1Δ+HAL2 after salt treatment showed that the GSH/GSSG ratio of bdf1Δ+HAL2 is much higher than that of WT+HAL2 (Chen and Bao, unpublished data). This result further suggests that HAL2 overexpression may reduce the ROS level of bdf1Δ under salt stress.

Under unfavorable conditions like nutrient deprivation, yeast cells can make molecules recycled by a non-selective autophagy process for their own cytosolic components with the autophagosomes, which are visible under the bright-field microscope [39], [40], [45]. Since Hal2p overexpression caused both positive and negative impacts on the mitochondria function (Fig. 6), we app:ds:conjecturespeculate that the non-selective degradation process in autophagy may play a role in this process.

Defective autophagy with high level of ROS and mitochondria dysfunction [46] was observed in bdf1Δ (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Overexpression of HAL2 in bdf1Δ induced autophagy, elevated the fluorescence intensity of GFP-Atg8p, partially restored mitochondrial function and Na+ resistance. This led us to conclude that Hal2p overexpression stimulates autophagy and the defect of autophagy in bdf1Δ could be one of the causes for Na+ sensitivity. We speculated that the autophagy induced by HAL2 overexpression is probably related to amino acids imbalance. The overexpression of HAL2, a participator of methionine biosynthesis, probably mediates some amino acids starvation, therefore inducing autophagy and recovering the salt stress sensitivity of bdf1Δ. This is further confirmed by our microarray analysis, which showed that many genes related to amino acids metabolism and iron acquisition were upregulated, when HAL2 was overexpressed in bdf1Δ (Chen and Bao, unpublished data).

2. Hal2p and Bdf1p respond to salt stress via different mechanisms

Methionine supplementation rescued the growth of hal2Δ mutants but not bdf1Δ mutants, suggesting the differences in Na+ stress response between HAL2 and BDF1. In addition, HAL2 overexpression recovered the cell growth of bdf1Δ under either Li+ or Na+ stress (Fig. 5F, G), but no significant difference of pAp accumulation was observed under Na+ stress suggesting that the mechanisms mediated by Bdf1p and Hal2p in response to these two salts are different.

HAL2 deficiency caused Na+ sensitivity but only on medium lacking amino acid (Fig. 5G, Line 4), possibly because Hal2p is related to amino acid metabolism [34]. The bdf1Δhal2Δ double deletion mutant showed enhanced sensitivity to NaCl compared to the two single deletion mutants (Fig. 5G, Lines 2, 4, 5). This result further suggests that the mechanism of Hal2p-mediated in Na+ stress response is different from that of Bdf1p-mediated.

One interesting phenomenon we observed is that unlike the S. cerevisiae RS-16 background strain [16], [34], no pAp was detected in W303 background strains even under a high level of NaCl stress (Fig. 5A–D). Under Li+ stress, there was a high level of pAp accumulation in both W303 wild type and the derived bdf1Δ and pAp accumulation in bdf1Δ cells under Li+ stress could be diminished by HAL2 overexpression (Fig. 5E). This indicated that pAp accumulation was not related to Na+ salt sensitivity of bdf1Δ. Methionine supplementation rescued the growth of hal2Δ mutants but not bdf1Δ mutants,

The difference in pAp accumulation between W303 and RS-16 is probably due to the different genotypes of the two strains. W303, but not RS-16, is ade1 mutant (Table 1) [16], [34]. As a result, the colony of W303 appears to be remarkably red, a sign of red pigment accumulation due to ade1 defect.

Supporting Information

Expression of BDF1 using a 2 μ plasmid enhanced the salt resistance of bdf1Δ . 5 µl aliquots of 10-fold serial dilutions of the mid-log phase cultures were spotted onto YPD plates with or without NaCl and incubated at 30°C for 3 d.

(TIF)

bdf1Δhal2Δ double deletion is more sensitive to salt stress. 5 µl aliquots of 10-fold serial dilutions of the mid-log phase cultures were spotted onto YPD plates with or without NaCl and incubated at 30°C for 3 d.

(TIF)

Primers used in the current study.

(DOCX)

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30170021, 30671143 and 30570031). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 2. Hirata D, Harada S, Namba H, Miyakawa T (1995) Adaptation to high-salt stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphoprotein phosphatase (calcineurin) and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol Gen Genet 249: 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Serrano R, Gaxiola R (1994) Microbial models and salt stress tolerance in plants. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 13: 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Serrano R, Mulet JM, Rios G, Marquez JA, de Larrinoa IF, et al. (1999) A glimpse of the mechanisms of ion homeostasis during salt stress. J Exp Bot 50: 1023–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chung J, Bachelder RE, Lipscomb EA, Shaw LM, Mercurio AM (2002) Integrin (alpha 6 beta 4) regulation of eIF-4E activity and VEGF translation: a survival mechanism for carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol 158: 165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Nadal E, Calero F, Ramos J, Ariño J (1999) Biochemical and genetic analyses of the role of yeast casein kinase 2 in salt tolerance. J Bacteriol 181: 6465–6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lygerou Z, Conesa C, Lesage P, Swanson RN, Ruet A, et al. (1994) The yeast BDF1 gene encodes a transcription factor involved in the expression of a broad class of genes including snRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 5332–5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sawa C, Nedea E, Krogan N, Wada T, Handa H, et al. (2004) Bromodomain factor 1(Bdf1) is phosphorylated by protein kinase CK2. Mol Cell Biol 24: 4734–4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ladurner AG, Inouye C, Jain R, Tjian R (2003) Bromodomains mediate an acetyl-histone encoded antisilencing function at heterochromatin boundaries. Mol Cell 11: 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matangkasombut O, Buratowski S (2003) Different sensitivities of bromodomain factors 1 and 2 to histone H4 acetylation. Mol Cell 11: 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pamblanco M, Poveda A, Sendra R, Rodríguez-Navarro S, Pérez-Ortín JE, et al. (2001) Bromodomain factor 1 (Bdf1) protein interacts with histones. FEBS Lett 496: 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matangkasombut O, Buratowski RM, Swilling NW, Buratowski S (2000) Bromodomain factor 1 corresponds to a missing piece of yeast TFIID. Genes Dev 14: 951–962. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krogan NJ, Keogh MC, Datta N, Sawa C, Ryan OW, et al. (2003) A Snf2 family ATPase complex required for recruitment of the histone H2A variant Htz1. Mol Cell 12: 1565–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Jesus Ferreira MC, Bao X, Laize V, Hohmann S (2001) Transposon mutagenesis reveals novel loci affecting tolerance to salt stress and growth at low temperature. Current Genetics 40: 27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu X, Yang H, Zhang X, Liu L, Lei M, et al. (2009) Bdf1p deletion affects mitochondrial function and causes apoptotic cell death under salt stress. FEMS Yeast Res 9: 240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murguía JR, Bellés JM, Serrano R (1996) The yeast HAL2 nucleotidase is an in vivo target of salt toxicity. J Biol Chem 271: 29029–29033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dichtl B, Stevens A, Tollervey D (1997) Lithium toxicity in yeast is due to the inhibition of RNA processing enzymes. EMBO J 16: 7184–7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomas D, Cherest H, Surdin-Kerjan Y (1989) Elements involved in S-adenosylmethionine -mediated regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MET25 gene. Mol Cell Biol 9: 3292–3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thomas D, Surdin-Kerjan Y (1997) Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol Biol Rev 61: 503–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sikorski RS, Hieter P (1989) A system of shuttle vectors and yeast strains desinged for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics 122: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Casalone E, Barberio C, Cavalieri D, Ceccarelli I, Riparbelli M, et al. (1999) Disruption and phenotypic analysis of six novel genes from chromosome IV of Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveal YDL060w as an essential gene for vegetative growth. Yeast 15: 1691–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wach A, Brachat A, Poehlmann R, Philippsen P (1994) New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10: 1793–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu X, Zhang X, Wang C, Liu L, Lei M, et al. (2007) Genetic and comparative transcriptome analysis of bromodomain factor 1 in the salt stress response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Curr Microbiol 54: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dunn T, Gable K, Beeler T (1994) Regulation of cellular Ca2+ by yeast vacuoles. J Biol Chem 269: 7273–7278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lim CK, Peters TJ (1989) Isocratic reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography of ribonucleotides, deoxynucleotides, cyclic nucleotides and deoxycyclic nucleotides. J Chromatogr 461: 259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Camougrand N, Grelaud-Coq A, Marza E, Priault M, Bessoule JJ, et al. (2003) The product of the UTH1 gene, required for Bax-induced cell death in yeast, is involved in the response to rapamycin. Mol Microbiol 47: 495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braunstein M, Rose AB, Holmes SG, Allis CD, Broach JR (1993) Transcriptional silencing in yeast is associated with reduced nucleosome acetylation. Genes Dev 7: 592–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petrangeli E, Lenti L, Buchetti B, Chinzari P, Sale P, et al. (2009) Lipido-sterolic extract of Serenoa repens (LSESr, Permixon) treatment affects human prostate cancer cell membrane organization. J Cell Physiol 219: 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haro R, Garciadeblas B, Rodríguez-Navarro A (1991) A novel P-type ATPase from yeast involved in sodium transport. FEBS Lett 291: 189–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wieland J, Nitsche AM, Strayle J, Steiner H, Rudolph HK (1995) The PMR2 gene cluster encodes functionally distinct isoforms of a putative Na+ pump in the yeast plasma membrane. EMBO J 14: 3870–3882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gläser HU, Thomas D, Gaxiola R, Montrichard F, Surdin-Kerjan Y, et al. (1993) Salt tolerance and methionine biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae involve a putative phosphatase gene. EMBO J 12: 3105–3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bianchi MM, Costanzo G, Chelstowska A, Grabowska D, Mazzoni C, et al. (2004) The bromodomain-containing protein Bdf1p acts as a phenotypic and transcriptional multicopy suppressor of YAF9 deletion in yeast. Mol Microbiol 53: 953–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Todeschini AL, Condon C, Benard L (2006) Sodium-induced GCN4 expression controls the accumulation of the 5′to 3′RNA degradation inhibitor, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate. J Biol Chem 281: 3276–3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chernyakov I, Whipple JM, Kotelawala L, Grayhack EJ, Phizicky EM (2008) Degradation of several hypomodified mature tRNA species in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is mediated by Met22 and the 5′-3′exonucleases Rat1 and Xrn1. Genes Dev 22: 1369–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tehlivets O, Scheuringer K, Kohlwein SD (2007) Fatty acid synthesis and elongation in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta 1771: 255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liang Q, Zhou B (2007) Copper and manganese induce yeast apoptosis via different pathways. Mol Biol Cell 18: 4741–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Knorre DA, Ojovan SM, Saprunova VB, Sokolov SS, Bakeeva LE, et al. (2008) Mitochondrial matrix fragmentation as a protection mechanism of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Biochemistry 73: 1254–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cebollero E, Reggiori F (2009) Regulation of autophagy in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 1413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Inoue Y, Klionsky DJ (2010) Regulation of macroautophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Semin. Cell Dev Biol 21: 664–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reggiori F, Klionsky DJ (2002) Autophagy in the eukaryotic cell. Eukaryot Cell 1: 11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kirisako T, Ichimura Y, Okada H, Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, et al. (2000) The reversible modification regulates the membrane-binding state of Apg8/Aut7 essential for autophagy and the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J Cell Biol 151: 263–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xie Z, Nair U, Klionsky DJ (2008) Atg8 controls phagophore expansion during autophagosome formation. Mol Biol Cell 19: 3290–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xie Z, Nair U, Geng J, Szefler MB, Rothman ED, et al. (2009) Indirect estimation of the area density of Atg8 on the phagophore. Autophagy 5: 217–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kissová I, Salin B, Schaeffer J, Bhatia S, Manon S, et al. (2007) Selective and non-selective autophagic degradation of mitochondria in yeast. Autophagy 3: 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Suzuki SW, Onodera J, Ohsumi Y (2011) Starvation Induced Cell Death in Autophagy-defective yeast mutants is caused by mitochondria dysfunction. PLoS ONE 6: e17412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression of BDF1 using a 2 μ plasmid enhanced the salt resistance of bdf1Δ . 5 µl aliquots of 10-fold serial dilutions of the mid-log phase cultures were spotted onto YPD plates with or without NaCl and incubated at 30°C for 3 d.

(TIF)

bdf1Δhal2Δ double deletion is more sensitive to salt stress. 5 µl aliquots of 10-fold serial dilutions of the mid-log phase cultures were spotted onto YPD plates with or without NaCl and incubated at 30°C for 3 d.

(TIF)

Primers used in the current study.

(DOCX)