Abstract

Background:

We previously demonstrated that AIB1 overexpression is an independent molecular marker for shortened survival of bladder cancer (BC) patients. In this study, we characterised the role and molecular mechanisms of AIB1 in BC tumorigenicity.

Methods:

AIB1 expression was measured by immunohistochemistry in non-muscle-invasive BC tissue and adjacent normal bladder tissue. In addition, the tumorigenicity of AIB1 was assessed with in vitro and in vivo functional assays.

Results:

Overexpression of AIB1 was observed in tissues from 46 out of 146 patients with non-muscle-invasive BC and was an independent predictor for poor progression-free survival. Lentivirus-mediated AIB1 knockdown inhibited cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo, whereas AIB1 overexpression promoted cell proliferation in vitro. The growth-inhibitory effect induced by AIB1 knockdown was mediated by G1 arrest, which was caused by reduced expression of key cell-cycle regulatory proteins through the AKT pathway and E2F1.

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that AIB1 promotes BC cell proliferation through the AKT pathway and E2F1. Furthermore, AIB1 overexpression predicts tumour progression in patients with non-muscle-invasive BC.

Keywords: bladder cancer, AIB1, AKT, E2F1, proliferation

Bladder cancer (BC) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in Western countries and is the sixth most common cancer in the world (Pelucchi et al, 2006; Jemal et al, 2010). In China, the incidence of BC continues to rise. BC can be classified as non-muscle-invasive or muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma. Most newly diagnosed BCs (70–90%) are non-muscle-invasive (stage Ta or T1). Approximately two-thirds of non-muscle-invasive BCs will recur after initial management, and 5–30% of these will progress to muscle-invasive BC – for which the 5-year mortality is 60–70% (Jemal et al, 2010). Biomarkers may help to identify patients with non-muscle-invasive BC at higher risk for disease progression who might benefit from early aggressive intervention. However, to date, the identification of promising biomarkers that define the potential for BC progression has remained substantially limited. Moreover, the molecular mechanism underlying BC progression is still unknown (Konety and Lotan, 2008).

The amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1) gene, also known as SRC3, p/CIP, RAC3, ACTR, and TRAM1, is located on chromosome 20q12 and has been classified as a human oncogene (Anzick et al, 1997). Initially identified as a coactivator for nuclear steroid hormone receptors such as oestrogen receptor and androgen receptor, AIB1 was reported to promote proliferation in hormone-dependent cancers. However, recent clinical studies showed that AIB1 upregulation was associated with tumour aggressiveness and/or poor patient prognosis in several human hormone-independent cancers, including pancreatic (Ghadimi et al, 1999), oesophageal (Xu et al, 2007), gastric (Sakakura et al, 2000), colorectal (Xie et al, 2005), hepatocellular (Wang et al, 2002), and nasopharyngeal carcinomas (Liu et al, 2008). Previously, we demonstrated that overexpression of AIB1 is an independent molecular marker for shortened survival of BC patients (Luo et al, 2008). To date, however, the potential oncogenic role of AIB1 and its molecular mechanisms in BC are still unclear.

In this study, we investigated the impact of abnormalities in AIB1 expression on BC pathogenesis. We examined AIB1 protein expression in a series of primary non-muscle-invasive BC and adjacent normal mucosa tissues and cells, and assessed the clinical and prognostic significance of AIB1 in this cohort. In addition, we investigated the tumorigenicity of AIB1 and the molecular mechanisms underlying its oncogenic effects.

Materials and methods

Patients

In this study, we used computer-generated random numbers to select 146 patients from 438 consecutive patients with primary non-muscle-invasive BC treated with transurethral resection (TUR-Bt) between January 2005 and December 2008 at First Affiliated Hospital, Jiangmen Hospital, and Cancer Centre of Sun Yat-sen University. Among the selected patients, there were 117 men and 29 women, and the median age was 63 years (range: 27–83 years). The histological grade and stage were reassessed according to the 2004 World Health Organisation grading system and the sixth edition of the TNM classification system, respectively. Paraffin specimens were obtained by biopsy or TUR-Bt, and 20 adjacent normal mucosa tissues were used as controls. Fifteen pairs of cancer tissues and adjacent normal bladder specimens were snap-frozen in chilled liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further processing. This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of our institute.

Treatments and follow-up

All patients were treated with TUR-Bt and postoperative intravesical instillations once weekly for the first 6 weeks and then monthly up to 1 year. A total of 85 patients were administered mitomycin C and 61 patients were administered pirarubicin. Cystoscopy was performed at 3-month intervals during the first 2 years and at 6-month intervals after 2 years. The mean follow-up time was 39.1 months (range: 5–53 months). Disease progression was defined as an instance in which the recurrent tumour had a higher tumour stage than the primary tumour (local progression) or an instance in which distant metastasis occurred (distant progression). Data from patients whose follow-up ended without manifestation of tumour progression were censored.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) evaluation

Immunohistochemical studies were performed using a standard streptavidin–biotin–peroxidase complex method (Liu et al, 2008). In brief, tissue sections were deparaffinised and rehydrated, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min. For antigen retrieval, tissue slides were boiled in 10 mℳ citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a pressure cooker for 10 min. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 10% normal rabbit serum for 20 min. The slides were incubated with anti-AIB1, a monoclonal antibody directed at amino acids 376–389 of AIB1 (clone 34; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA, USA; diluted 1 : 50 in PBS), overnight at 4 °C. All incubations were performed in a moist chamber. Subsequently, the slides were sequentially incubated with biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin at a concentration of 1 : 100 for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, they were treated with a streptavidin–peroxidase conjugate for 30 min at 37 °C and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as a chromogen substrate. The nucleus was counterstained using Meyer's hematoxylin. Normal murine IgG was used in place of the primary antibody for negative controls. Known immunostaining positive slides of BC were used as positive controls. Positive expression of AIB1 in BC cells and in normal bladder mucosa cells was primarily detected in the nucleus.

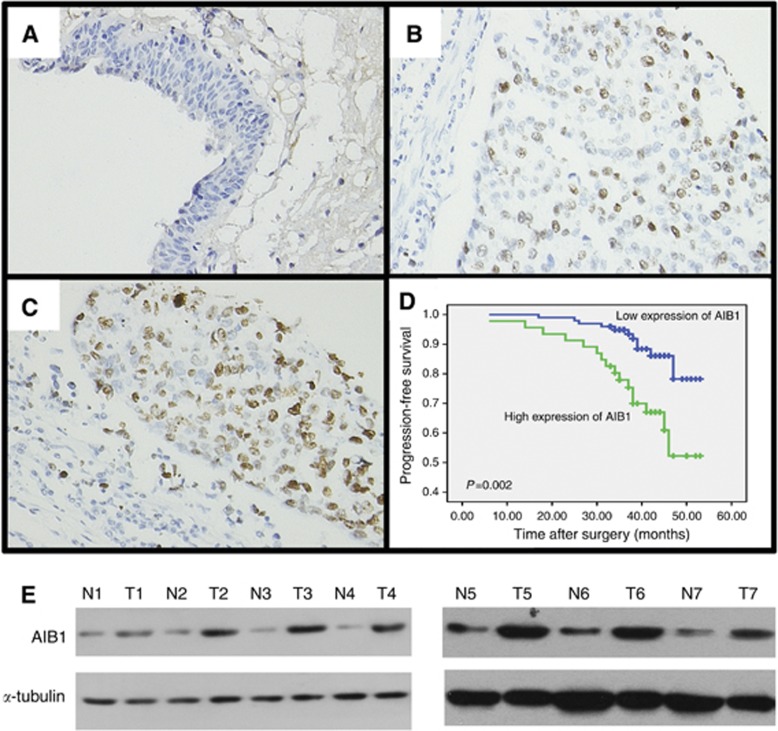

To evaluate the results of AIB1 IHC staining, the cancerous and noncancerous tissues were scored by assessing the percentage of positive cells with nuclear expression of AIB1 in each tissue section. Because AIB1 expression was detected in up to 10% of the epithelium of normal bladder mucosa, 0–10% was considered normal AIB1 expression (Figure 1A), whereas AIB1 expression in the nucleus of >10% cells was considered AIB1 overexpression (Figure 1B and C). Two independent observers blinded to clinicopathological information performed scoring.

Figure 1.

Expression and prognostic significance of amplified in breast cancer (AIB1) in BC. (A) Representative image of negative AIB1 IHC staining in normal bladder tissues. (B) Representative image of weak AIB1 IHC staining in BC tissues. (C) Representative image of positive AIB1 IHC staining in BC tissues. (D) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis according to AIB1 expression in 146 patients with non-muscle-invasive BC (log-rank test). (E) Western blotting analysis of AIB1 protein expression in pairs of matched BC (T) and adjacent normal tissues (N).

Western blotting

Equal amounts of whole tissue or cell lysates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) before incubation with primary antibodies against AIB1, p-AKT, AKT, E2F1, c-myc, cyclin D1, cyclin E, p27, CDK4, p21, or α-tubulin (BD Transduction Laboratories). The immunoreactive proteins were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell cultures and stable transfectants

Four BC cell lines – EJ (derived from an advanced grade 4 transitional cell carcinoma), BIU-87 (established from the bladder papillary urothelial carcinoma (T1G2)), 5637 (derived from the primary grade II bladder carcinoma), and T24 (established from a highly malignant grade III human urinary bladder carcinoma) – were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. A total of 5637 cells ectopically expressing were transfected with pcD-HCMV-AIB1-HA (AIB1 expression vector) or pcD-HCMV (empty vector), which were kindly provided by Professor Hongwu Chen (University of California at Davis), using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Transfected cells were selected in medium containing G418 (700 μg ml−1). Levels of ectopic AIB1 expression in individual clones were analysed by western blotting using AIB1 antibodies (BD Transduction Laboratories). EJ-shAIB1 cells were transfected with pUSEamp-myr-akt and pUSEamp empty vector (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Lake Placid, NY, USA). The ectopic expression of myr-AKT was detected by western blotting using tag myc antibodies.

AIB1 knockdown by lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA)

The vector pLLU2G, a kind gift from Professor Peng Xiang (Center for Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering, Sun Yat-sen University), was derived from pLL3.7 and contains separate GFP and shRNA expression elements, as well as elements required for lentiviral packaging (Dann et al, 2006). The two target sequences of AIB1 for constructing lentiviral shRNA are as follows: AIB1-shRNA1: 5′-AGACTCCTTAGGACCGCTT-3′ AIB1-shRNA2: 5′-GGTCTTACCTGCAGTGGTGAA-3′. Virus packaging was performed by transient transfection of 293FT cells with a transfer plasmid and three packaging vectors: pMDLg/pRRE, pRSV-REV, and pCMV-VSVG. Seventy-two hours after transfection, the lentiviral particles were collected and filtered, and then concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 50 000 g for 2.5 h at 4 °C. Subsequently, we infected the BC cell lines EJ and T24 with the lentivirus in a 24-well plate. Four days after infection, the knockdown efficiency of AIB1 was examined by western blotting.

MTT proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured with the use of MTT assay (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, about 1000 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cell proliferation was examined on 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 days followed the standard procedures. All experiments were repeated three times.

Colony-formation assay

EJ-shLuc, EJ-shAIB1, T24-shLuc, T24-shAIB1, 5637-pcD-HCMV-AIB1-HA, and 5637-pcD-HCMV cells were seeded in six-well plates at 500 cells per well. After incubation for 14 days, surviving colonies (>50 cells per colony) were stained with Giemsa (Invitrogen) and scored while being viewed under a dissecting microscope. All experiments were done in triplicate.

Cell-cycle analysis

EJ-shAIB1, EJ-shLuc, T24-shAIB1, T24-shLuc, 5637-pcD-HCMV-AIB1-HA, 5637-pcD-HCMV, EJ-shAIB1-pUSEamp, and EJ-shAIB1-pUSEamp-myr-AKT cells seeded in a six-well plate at a density of 15 × 105 cells per well were detached using trypsin and fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol. Cells were subsequently stained for cell-cycle analysis using a Coulter DNA-Prep Reagents kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Cellular DNA content from each sample was determined with FacScan apparatus (Beckman Coulter). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Tumour xenografts in nude mice

Female BALB/c-nu/nu athymic mice (4–5 weeks old), purchased from Shanghai Slac Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China), were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions and cared for in accordance with the guidelines of the laboratory animal ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen University. For the xenograft tumour growth assay, EJ-AIB1-shRNA1, which is more efficient against AIB1, or control EJ-shLuc cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of the mice (10 mice per group), and this was performed in triplicate. Two weeks after inoculation, tumour size was measured every 3–4 days until the tumours grew to a diameter of 20 mm or when the tumour burden exceeded 10% of the body weight, at which time the mice were killed by cervical dislocation. Tumour volume was calculated by the formula V=ab2/2, where a=longest axis and b=shortest axis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

ChIP assays were carried out with a ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification was performed using 25 μl of purified ChIP DNA with promoter-specific primers. The primer sequences for cyclin E, E2F1, and cyclin D1 were described previously (Louie et al, 2004; Zou et al, 2006). The primer sequences for c-myc were 5′-GGCTTCTCAGAGGCTTGGCGGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCCAGCGTCTAAGCAGCTGCAA-3′ (reverse). To ensure the PCR reaction was in the linear range, 25–38 cycles were performed. The final products were separated on 2% agarose gel and visualised after staining with ethidium bromide. Each ChIP assay was repeated three times and a representative result was presented.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

Dual luciferase reporter assay was performed as described previously (Tong et al, 2012) with slight modification. Briefly, the treated 5637 cells were lysed, and the activities of the firefly and Renilla luciferases were analysed using a dual luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All reporter gene assays were performed in triplicate and repeated twice. The results were expressed as the mean±s.e.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (SPSS Standard version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two groups were compared using χ2-test for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted from progression-free survival data. The univariate Cox proportional regression hazard model was used to analyse the correlation between variables and clinical outcomes. Multivariate survival analysis was performed on all parameters that were significant on univariate analysis using the Cox regression model. Of the prognostic parameters that contributed significantly to the model, the effect was calculated in terms of odds ratios and the associated 95% confidence intervals. Probability values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The expression of AIB1 in BC

The clinicopathological characteristics of the 146 patients studied were summarised in Table 1. Using the criteria described above, we found overexpression of AIB1 in 46 (31.5%) cancer tissue specimens. No significant correlation was found between AIB1 expression and patient age or sex, or tumour grade, stage, size, or multiplicity (P>0.05, Table 1). The immunohistochemistry results were confirmed by western blotting for AIB1 protein expression in 15 pairs of non-muscle-invasive BC and adjacent normal bladder specimens. Seven (46.7%) BCs showed upregulated AIB1 expression compared with adjacent normal bladder tissues. The seven non-muscle-invasive BC cases with upregulated expression of AIB1 are shown in Figure 1E.

Table 1. Association of AIB1 expression with clinicopathological characteristics of 146 patients with non-muscle-invasive BC.

| |

AIB1 protein | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Cases | Overexpression (%) | P-value |

| Gender |

|

|

0.700 |

| Male | 117 | 36 (30.8%) | |

| Female |

29 |

10 (34.5%) |

|

| Age (years) |

|

|

0.596 |

| ⩽60 | 65 | 19 (29.2%) | |

| >60 |

81 |

27 (33.3%) |

|

| pT status |

|

|

0.751 |

| pTa | 101 | 31 (30.7%) | |

| pT1 |

45 |

15 (33.3%) |

|

| WHO grade |

|

|

0.394 |

| Low grade | 93 | 27 (29.0%) | |

| High grade |

53 |

19 (35.8%) |

|

| Tumour multiplicity |

|

|

0.321 |

| Unifocal | 88 | 25 (28.4%) | |

| Multifocal |

58 |

21 (36.2%) |

|

| Tumour size |

|

|

0.119 |

| ⩽2.0 cm | 71 | 18 (25.3%) | |

| >2.0 cm | 75 | 28 (37.3%) | |

Abbreviations: pT=pathological T(TNM); WHO=World Health Organisation.

Correlation between AIB1 expression and tumour progression

A total of 18.5% (27/146) of patients showed tumour progression after an average of 39.1 months. Univariate Cox regression analysis identified AIB1 expression, clinical stage, tumour grade, and size to have a significant impact on progression-free survival (P=0.003, 0.002, 0.014 and 0.021, respectively; Table 2). Other clinicopathological variables, including age, sex, tumour multiplicity, and intravesical instillation regimen, showed no significant correlation with progression-free survival (P>0.05, Table 2). The parameters that were significant in univariate analysis were further examined in Cox regression multivariate analysis. The results showed that the expression of AIB1 (P=0.009, Figure 1D), tumour stage (P=0.003), and tumour grade (P=0.016) were independent predictors of tumour progression (Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis on the contribution of various potential prognostic parameters to progression-free survival of patients with non-muscle-invasive BC.

| Parameters | Categories | P-value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Univariate Cox regression analysis | ||||

| AIB1 expression | Normal vs over | 0.003 | 3.182 | 1.476–6.862 |

| Gender | Male vs female | 0.145 | 0.407 | 0.122–1.361 |

| Age (years) | ⩽60 vs >60 | 0.273 | 1.564 | 0.702–3.483 |

| pT status | pTa vs pT1 | 0.002 | 3.252 | 1.522–6.946 |

| WHO grade | Low vs high | 0.014 | 2.589 | 1.211–5.537 |

| Multiplicity | Unifocal vs multifocal | 0.357 | 1.426 | 0.670–3.036 |

| Tumour size (cm) | ⩽2.0 vs >2.0 | 0.021 | 2.603 | 1.158–5.847 |

| Intravesical instillation |

MMC vs THP |

0.944 |

0.983 |

0.618–1.564 |

|

Multivariate Cox regression analysis | ||||

| AIB1 expression | Normal vs over | 0.009 | 2.861 | 1.307–6.264 |

| pT status | pTa vs pT1 | 0.003 | 3.296 | 1.520–7.148 |

| WHO grade | Low vs high | 0.016 | 2.585 | 1.196–5.586 |

| Tumour size (cm) | ⩽2.0 vs >2.0 | 0.068 | 2.144 | 0.945–4.866 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; MMC=mitomycin C; OR=odds ratio; pT=pathological T(TNM); THP=pirarubicin; WHO=World Health Organisation.

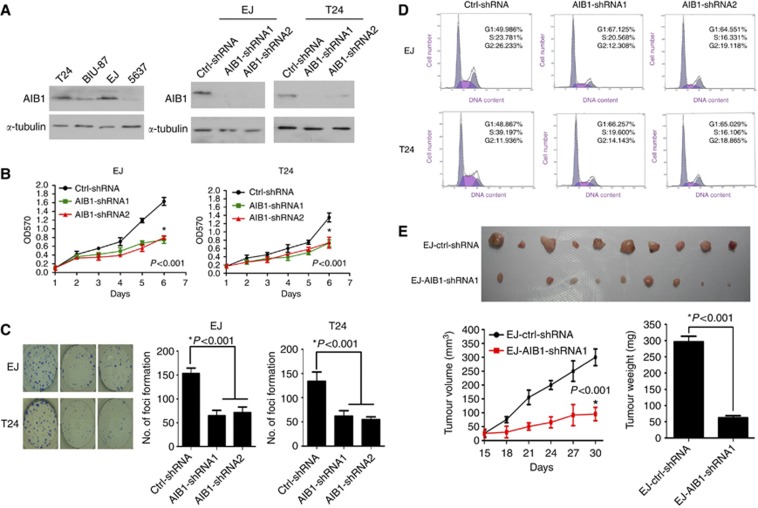

Short hairpin RNA-mediated AIB1 knockdown inhibited BC cell growth and proliferation in vitro and in vivo

To investigate the impact of AIB1 on BC cell line growth and proliferation, we first analysed AIB1 expression in four tumour-derived BC cell lines – EJ, BIU-87, T24, and 5637 – by western blotting. As shown in Figure 2A, EJ and T24 cells showed relatively higher levels of endogenous AIB1 protein expression to BIU-87 and 5637 cell lines. Subsequently, we infected EJ and T24 cells with lentivirus carrying shRNAs targeting AIB1. shAIB1 almost completely depleted intracellular AIB1 protein compared with control (shLuc), indicating high-efficiency AIB1 gene silencing (Figure 2A, right). MTT assay showed that knockdown of AIB1 dramatically reduced the proliferation of both EJ and T24 cells (Figure 2B). In agreement with this, the efficiency of foci formation was significantly inhibited (P<0.001) in EJ-shAIB1 and T24-shAIB1 cells compared with shLuc cells (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Depletion of endogenous AIB1 inhibited BC cell growth and proliferation in vitro and in vivo. (A) Western blotting analysis of BC cell lines showing endogenous AIB1 expression (left panel) and almost complete elimination of AIB1 expression after AIB1 knockdown in EJ and T24 cell lines (right panel). (B) Suppression of AIB1 in EJ and T24 cells dramatically reduced their proliferative ability, as determined by MTT assay. *P<0.001 by one-way ANOVA. (C) AIB1 knockdown in EJ and T24 cells markedly reduced their ability to form foci, as determined by the foci-formation assay. *P<0.001 by one-way ANOVA. (D) Cell-cycle analysis revealed that knocking down AIB1 expression in EJ and T24 cells increased the percentage of cells in the G1 phase and decreased the percentage in S phase. (E) Suppression of AIB1 dramatically inhibited tumor growth and proliferation in vivo as determined by a subcutaneous xenograft mice model. Actual sizes of representative tumours are shown in the upper panel, and the mean volume and weight of the tumours is shown in the lower panel. Results are presented as mean±s.e. (n=10 tumours). *P<0.001 by Student's t-test.

To investigate whether growth inhibition upon AIB1 depletion is related to alterations in the cell-cycle profile of BC cells, we analysed cellular DNA content with flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 2D, AIB1 knockdown in EJ and T24 cells induced G1 arrest.

To evaluate the effect of AIB1 depletion on BC cell growth in vivo, athymic nude mice were subcutaneously injected with EJ-shAIB1 cells or control EJ-shLuc cells. Tumours in mice injected with EJ-shAIB1 cells grew slower than those injected with control EJ-shLuc cells. One month after injection, the mean tumour volume and weight in mice injected with EJ-shAIB1 cells were significantly smaller than in mice injected with EJ-shLuc cells (Figure 2E).

Taken together, these data show that AIB1 is a significant determinant for BC cell growth and proliferation. Furthermore, AIB1 contributes to cell-cycle progression from G1 to S phase in BC cells.

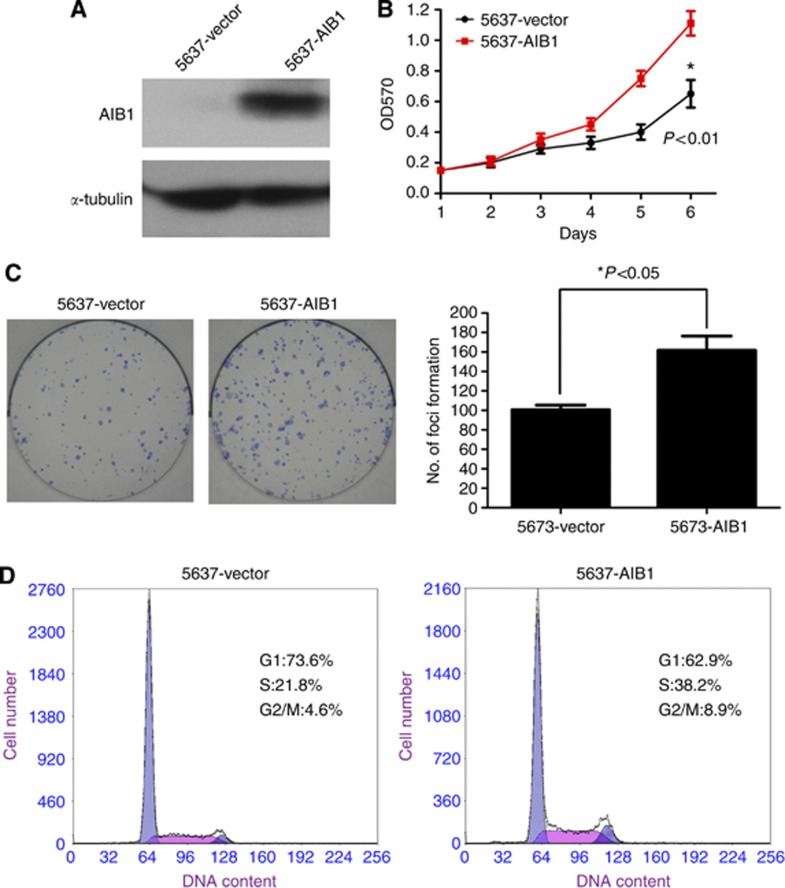

Ectopic overexpression of AIB1 promoted growth and proliferation of BC 5637 cells in vitro

To further determine the role of AIB1 in controlling BC cell growth and proliferation, we transfected BC 5637 cells, which showed almost undetectable expression of endogenous AIB1, with an AIB1 expression vector (Figure 3A). Using the MTT and foci-formation assays, we found that ectopic expression of AIB1 enhanced 5637 cell proliferation and growth compared with the control cells (Figure 3B and C, respectively). In addition, ectopic expression of AIB1 increased the percentage of 5637 cells in S phase, as determined with flow cytometry (Figure 3D). Collectively, these results provide evidence that elevated expression of AIB1 is important for the growth and proliferation of BC cells.

Figure 3.

Ectopic overexpression of AIB1 promoted growth and proliferation of BC 5637 cells in vitro. (A) Levels of ectopically expressed AIB1 in 5637 cells were examined by western blotting. (B) Representative results of MTT assays demonstrate that 5637-pcD-HCMV-AIB1-HA cells showed more proliferative ability than 5637-pcD-HCMV cells. *P<0.01 by Student's t-test. (C) Ectopic expression of AIB1 increased foci formation, as determined by the foci-formation assay. The number of foci formed by the 5637-pcD-HCMV and 5637-pcD-HCMV-AIB1-HA groups are shown in the right panel. Results are reported as mean±s.e. *P<0.05 by Student's t-test. (D) Ectopic expression of AIB1 decreased the percentage of cells in the G1 phase and increased the percentage of cells in S phase, as revealed by cell-cycle analysis.

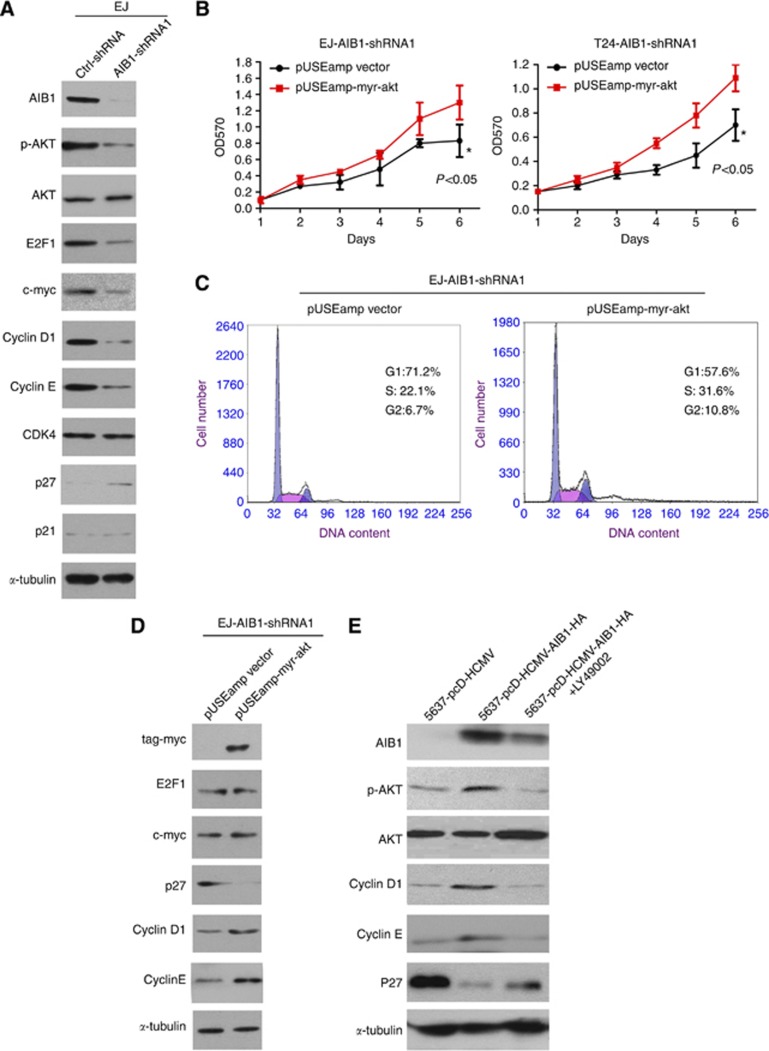

AIB1 promotes BC cell growth and proliferation though the AKT pathway and E2F1

Because our results suggested that AIB1 has a role in the transition from G1 to S phase in BC cells, we used western blotting to analyse the expression of key cell-cycle regulatory proteins after modulating AIB1 expression. As shown in Figure 4A, AIB1 knockdown in EJ cells reduced the expression of p-AKT, E2F1, c-myc, cyclin D1, and cyclin E, and induced p27 expression. No changes were noted in CDK4 and p21 levels.

Figure 4.

Depletion of AIB1 altered expression of the AKT pathway and key cell-cycle regulatory proteins. (A) Western blotting revealed that AIB1 knockdown in EJ cells caused a decrease in p-AKT, E2F1, c-myc, cyclin D1, and cyclin E and an increase in p27. (B) Transfection of constitutively activated AKT (myr-AKT) into EJ-shAIB1 and T24-shAIB1 cells restored proliferation, as determined by MTT assay. *P<0.05 by Student's t-test. (C) Upon myr-AKT transfection into EJ-AIB1-shRNA1 cells, the percentage of cells in G1 phase decreased and the percentage in S phase increased. (D) Introduction of myr-AKT into EJ-AIB1-shRNA1 cells restored the levels of E2F1, c-myc, cyclin D1, and cyclin E and reduced the levels of p27 protein compared with control vector. (E) In 5637 cells ectopically expressing AIB1, p27 levels were partially restored, whereas p-AKT, cyclin D1, and cyclin E levels decreased.

To confirm that the AKT pathway is indeed involved in AIB1-mediated regulation of BC proliferation, we transfected constitutively active AKT (myr-AKT) into EJ-shAIB1 cells and observed the cells' proliferative ability. The MTT assay showed, as anticipated, that EJ-shAIB1 cells regained high proliferative capability upon expression of myr-AKT (Figure 4B). Consistently, we also observed that the percentage of cells in G1 phase decreased concurrently with an increased percentage in S phase (Figure 4C).

Next, we performed western blotting to assess the effect of myr-AKT expression on the levels of E2F1, c-myc, cyclin D1, cyclin E, and p27 in EJ-shAIB1 cells. As shown in Figure 4D, ectopic expression of myr-AKT in EJ-shAIB1 cells increased the levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin E, which was accompanied by a decrease in p27; intriguingly, it did not alter the expression of E2F1 or c-myc. These results suggest that another heretofore unknown mechanism, and not the AKT pathway, is involved in AIB1-mediated upregulation of E2F1 and c-myc expression.

Moreover, we also found that p-AKT, cyclin D1, and cyclin E levels increased and p27 levels decreased when AIB1 was ectopically overexpressed in 5637 cells. However, treatment with PI3K inhibitor LY294002 partially restored p27 levels and reduced p-AKT, cyclin D1, and cyclin E levels in AIB1-overexpressing 5637 cells (Figure 4E). These data further support involvement of the AKT pathway in AIB1-mediated regulation of BC cell proliferation.

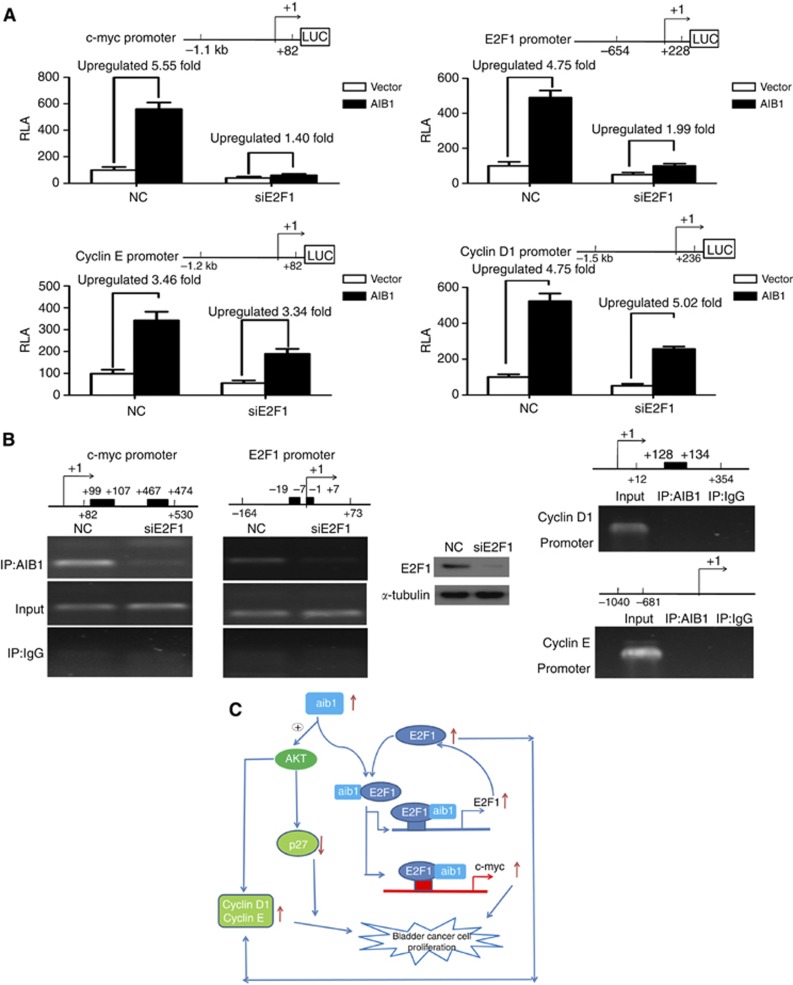

Because previous studies provided evidence that AIB1 coactivates E2F1 and promotes breast cancer cell proliferation (Louie et al, 2004), we hypothesised that E2F1 may also be involved in AIB1-mediated regulation of cell-cycle genes. As illustrated in Figure 5A, luciferase reporter assays showed that E2F1 was required for the transcriptional activity of AIB1 on the c-myc and E2F1 promoters (upregulated ratio: 5.55 vs 1.40 for c-myc; 4.75 vs 1.99 for E2F1; Figure 5A upper panel), but was not required for AIB1 activity on the cyclin E and cyclin D1 promoters (upregulated ratio: 3.46 vs 3.34 for cyclin E; 5.23 vs 5.02 for cyclin D1; Figure 5A lower panel). Similarly, ChIP assay showed an obvious decrease in AIB1 recruitment to the E2F1-binding site in the c-myc or E2F1 promoter in E2F1-silenced EJ cells, in contrast to control cells. We did not find AIB1 present on the promoter of cyclin D1 or cyclin E (Figure 5B). Collectively, these data suggest that AIB1 may regulate E2F1 and c-myc expression by functioning as a transcriptional coactivator of E2F1, rather than through the AKT pathway.

Figure 5.

AIB1 increased E2F1 and c-myc expression by acting as a coactivator of E2F1. (A) 5637 cells were first transfected with siE2F1 or control siRNA. After 36 h, the cells were co-transfected with the pGL3-indicated gene promoter luciferase, pRL-TK Renilla luciferase construct, and pcD-HCMV-AIB1-HA or pcD-HCMV plasmid. Thirty-six hours later, the luciferase activity of the cyclin D1, cyclin E, c-myc, or E2F1 promoter was measured and normalised relative to luciferase activity. The bar shows the average±s.d. of three independent experiments. (B) EJ cells were transfected with negative control siRNA or siE2F1. Forty-eight hours later, the ChIP experiment was carried out to evaluate the enrichment of AIB1 on the c-myc and E2F1 promoters (left panel). The knockdown efficiency of E2F1 was assessed by western blotting (insert). ChIP assay revealed no AIB1 on the cyclin D1 or cyclin E promoter (right panel). Regions of genomic sequence analysed by PCR are indicated on the schematic of each gene promoter. The black rectangular frame in each schematic represents potential E2F1-binding sites analysed with the Transcription Element Search System (at http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess?RQ=SEA-FR-Query) by entering human E2F1 accession number (TRANSFAC) T01542 in the factor filter option. (C) Proposed schematic of the potential mechanisms by which AIB1 stimulates BC cell proliferation.

Discussion

In this study, we found that high expression of AIB1 was an independent predictor of poor progression-free survival for patients with non-muscle-invasive BC. These findings identify AIB1 as a potential prognostic marker that may help guide individual therapeutic management of patients with non-muscle-invasive BC.

AIB1 is correlated with tumour progression after TUR-Bt of BC, and our results show that AIB1 is upregulated in BC (Luo et al, 2008). This suggests that AIB1 may have a key role in the development and/or growth of BC. Previous studies implicate AIB1 in the development and function of the mammalian reproductive system. Aib1−/− mice displayed many developmental defects, including retarded growth and small body size, suggesting that AIB1 regulates proliferation in normal tissues (Xu et al, 2000; Ying et al, 2005; Han et al, 2006). In cancer tissues, AIB1 upregulation promotes proliferation and tumour growth in a broad spectrum of cancers, such as breast and prostate (Louie et al, 2004; Zhou et al, 2005). In our recent study, we observed a positive correlation between AIB1 expression and Ki-67 expression in our cohort of patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (Luo et al, 2008). These results suggested that AIB1 may exert oncogenic effects in BC partly by promoting cell proliferation. To test this, AIB1 expression was initially detected by western blotting in four human bladder carcinoma cell lines, T24, BIU-87, EJ, and 5637. The T24 and EJ cell lines exhibited relatively high levels of endogenous AIB1, whereas the 5637 cell line showed almost undetectable levels of AIB1. Further functional studies demonstrated that shRNA-mediated silencing of AIB1 expression in both EJ and T24 cells led to G1 arrest, decreased foci-formation ability, and reduced cell growth and proliferation in vitro and in vivo. AIB1 overexpression in 5637 cells elicited the opposite effect. These data support our emerging view that AIB1 is an important factor in BC cell proliferation and tumour growth.

The AIB1 gene was initially recognised as a member of the steroid receptor coactivator family, and that it identified as a transcriptional coactivator of steroid receptors, such as oestrogen receptor (Anzick et al, 1997), progesterone receptor (Han et al, 2006), and androgen receptor (Gnanapragasam et al, 2001), then recruited to the promoter/enhancer of target genes by nuclear receptors, leads to further recruit other factors, such as acetyltransferases (CBP and p300), histone acetyltransferases, and methyltransferases (CARM1 and PRMT1) to mediate chromatin remodelling and enhance receptor-dependent transcription (McKenna and O'Malley, 2002). However, there are cumulative clinical studies showing that AIB1 is also associated with cancers that are not hormone dependent, such as gastric (Sakakura et al, 2000), liver (Wang et al, 2002), pancreatic (Ghadimi et al, 1999), and colon (Xie et al, 2005). Consistent with this, our previous results showed that BC cases displayed negative staining for progesterone receptor and androgen receptor, and no significant correlations were found between the expression of AIB1 and oestrogen receptor (Luo et al, 2008). This suggested that AIB1 may promote BC cell growth and proliferation through a hormone-independent pathway. Thus, several key cell-cycle genes associated with the G1 to S phase transition were examined by western blotting. Concomitant with a decrease in AIB1 by shRNA-mediated knockdown was a decrease in the expression of c-myc, cyclin D1, cyclin E, and E2F1. AIB1 has been reported to induce cell proliferation and tumorigenesis by activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway (Zhou et al, 2003; Oh et al, 2004; Torres-Arzayus et al, 2004), which is also implicated in BC progression (Oka et al, 2006; Eblin et al, 2007). Thus, as expected, repressed AIB1 expression coincided with significantly reduced p-AKT levels, and these results were confirmed by the reverse experiment – introducing constitutively active AKT (myr-AKT) into EJ-shAIB1 cells. Interestingly, myr-AKT indeed restored cyclin D1 and cyclin E expression and reduced p27 expression, but it did not restore E2F1 or c-myc expression, suggesting that another mechanism was also involved in AIB1's effects on BC cell cycle.

AIB1 has also been identified as a coactivator for transcription factors, including E2F1 (Louie et al, 2004), AP-1 (Lee et al, 1998), NF-κB (Werbajh et al, 2000), STAT6 (Arimura et al, 2004), and PEA3 (Qin et al, 2008). Given that cyclin D1, cyclin E, c-myc, and E2F1 itself are well-characterised targets of transcriptional regulation by E2F1 (DeGregori et al, 1995; Muller et al, 2001; Ren et al, 2002; Trimarchi and Lees, 2002), we examined whether the E2F1 pathway is involved in AIB1-mediated control of their expression. Interestingly, using a luciference reporter assay, we found that AIB1's transcriptional activity on c-myc and E2F1 was dependent on the presence of E2F1, whereas its transcriptional activity on cyclin D1 and cyclin E was not. This finding was supported by a ChIP experiment showing that AIB1 enrichment on the c-myc and E2F1 promoters was almost completely eliminated when endogenous E2F1 was inhibited. We did not detect the presence of AIB1 on the promoter of cyclin D1 or cyclin E.

Based on previous studies (Louie et al, 2004; Oh et al, 2004; Torres-Arzayus et al, 2004; Yan et al, 2006) and the results from our current study, we propose that AIB1 promotes BC cell proliferation through at least two distinct mechanisms. In one mechanism, AIB1 controls expression of the key cell-cycle genes cyclin D1, cyclin E, and p27 by activating the AKT pathway, and this function can be abolished by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002. In the other mechanism, AIB1 promotes E2F1 and c-myc expression by functioning as a coactivtor of E2F1 in a hormone-independent manner. Importantly, these two mechanisms are expected to cross-talk. The increased expression of E2F1 triggered by AIB1 enhanced the upregulated function of AIB1 on cyclin D1 and cyclin E by the PI3K/AKT pathway. Because AIB1 is a coactivator of many other transcription factors, it is possible that AIB1 may modulate cell growth and proliferation through these other factors. A schematic representation of the potential molecular mechanisms underlying AIB1's effects in BC is provided in Figure 5C. More studies are needed to confirm this model and elucidate whether other signalling pathways also contribute to the BC growth and proliferation mediated by AIB1 expression.

In summary, AIB1 overexpression seems to indicate an aggressive phenotype of non-muscle-invasive BC with high risk of disease progression after initial treatment. Further functional study revealed that AIB1 promotes BC cell proliferation and tumour growth by activating the AKT pathway and acting as coactivator of E2F1. These findings may be helpful in clinical practice for selecting non-muscle-invasive BC patients who might require a more intensive follow-up and/or more aggressive treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30900539, 81201743, and 81172429), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (09ykpy35), the Science and Information Technology Foundation of Guangzhou (2011J2200065), and the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Foundation (2008B030301112 and 2010B031600036). We thank Professor Jheri Dupart for improving the language and presentation of this manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

- Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, Azorsa DO, Tanner MM, Guan XY, Sauter G, Kallioniemi OP, Trent JM, Meltzer PS. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1997;277:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura A, van Peer M, Schroder AJ, Rothman PB. The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP (NCoA-3) is up-regulated by STAT6 and serves as a positive regulator of transcriptional activation by STAT6. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31105–31112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann CT, Alvarado AL, Hammer RE, Garbers DL. Heritable and stable gene knockdown in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11246–11251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604657103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGregori J, Kowalik T, Nevins JR. Cellular targets for activation by the E2F1 transcription factor include DNA synthesis- and G1/S-regulatory genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4215–4224. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eblin KE, Bredfeldt TG, Buffington S, Gandolfi AJ. Mitogenic signal transduction caused by monomethylarsonous acid in human bladder cells: role in arsenic-induced carcinogenesis. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:321–330. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadimi BM, Schrock E, Walker RL, Wangsa D, Jauho A, Meltzer PS, Ried T. Specific chromosomal aberrations and amplification of the AIB1 nuclear receptor coactivator gene in pancreatic carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:525–536. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65298-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnanapragasam VJ, Leung HY, Pulimood AS, Neal DE, Robson CN. Expression of RAC 3, a steroid hormone receptor co-activator in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1928–1936. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SJ, DeMayo FJ, Xu J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-1 and SRC-3 differentially modulate tissue-specific activation functions of the progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:45–55. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konety B, Lotan Y. Urothelial bladder cancer: biomarkers for detection and screening. Bju Int. 2008;102:1234–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Kim HJ, Na SY, Kim TS, Choi HS, Im SY, Lee JW. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 coactivates activating protein-1-mediated transactivations through interaction with the c-Jun and c-Fos subunits. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16651–16654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MZ, Xie D, Mai SJ, Tong ZT, Shao JY, Fu YS, Xia WJ, Kung HF, Guan XY, Zeng YX. Overexpression of AIB1 in nasopharyngeal carcinomas correlates closely with advanced tumor stage. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:728–734. doi: 10.1309/QMDTL82JKEX6E7H2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie MC, Zou JX, Rabinovich A, Chen HW. ACTR/AIB1 functions as an E2F1 coactivator to promote breast cancer cell proliferation and antiestrogen resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5157–5171. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5157-5171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JH, Xie D, Liu MZ, Chen W, Liu YD, Wu GQ, Kung HF, Zeng YX, Guan XY. Protein expression and amplification of AIB1 in human urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and overexpression of AIB1 is a new independent prognostic marker of patient survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2554–2561. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell. 2002;108:465–474. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller H, Bracken AP, Vernell R, Moroni MC, Christians F, Grassilli E, Prosperini E, Vigo E, Oliner JD, Helin K. E2Fs regulate the expression of genes involved in differentiation, development, proliferation, and apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:267–285. doi: 10.1101/gad.864201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh A, List HJ, Reiter R, Mani A, Zhang Y, Gehan E, Wellstein A, Riegel AT. The nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1 mediates insulin-like growth factor I-induced phenotypic changes in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8299–8308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka N, Tanimoto S, Taue R, Nakatsuji H, Kishimoto T, Izaki H, Fukumori T, Takahashi M, Nishitani M, Kanayama HO. Role of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt pathway in bladder cancer cell apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1093–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelucchi C, Bosetti C, Negri E, Malvezzi M, La Vecchia C. Mechanisms of disease: the epidemiology of bladder cancer. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2006;3:327–340. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Liao L, Redmond A, Young L, Yuan Y, Chen H, O'Malley BW, Xu J. The AIB1 oncogene promotes breast cancer metastasis by activation of PEA3-mediated matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) and MMP9 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5937–5950. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00579-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B, Cam H, Takahashi Y, Volkert T, Terragni J, Young RA, Dynlacht BD. E2F integrates cell cycle progression with DNA repair, replication, and G(2)/M checkpoints. Genes Dev. 2002;16:245–256. doi: 10.1101/gad.949802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakura C, Hagiwara A, Yasuoka R, Fujita Y, Nakanishi M, Masuda K, Kimura A, Nakamura Y, Inazawa J, Abe T, Yamagishi H. Amplification and over-expression of the AIB1 nuclear receptor co-activator gene in primary gastric cancers. Int J Cancer. 2000;89:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong ZT, Cai MY, Wang XG, Kong LL, Mai SJ, Liu YH, Zhang HB, Liao YJ, Zheng F, Zhu W, Liu TH, Bian XW, Guan XY, Lin MC, Zeng MS, Zeng YX, Kung HF, Xie D. EZH2 supports nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell aggressiveness by forming a co-repressor complex with HDAC1/HDAC2 and Snail to inhibit E-cadherin. Oncogene. 2012;31:583–594. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Arzayus MI, de Mora JF, Yuan J, Vazquez F, Branson R, Rue M, Sellers WR, Brown M. High tumor incidence and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in transgenic mice define AIB1 as an oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi JM, Lees JA. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2002;3:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wu MC, Sham JST, Zhang WG, Wu WQ, Guan XY. Prognostic significance of c-myc and AIB1 amplification in hepatocellular carcinoma—a broad survey using high-throughput tissue microarray. Cancer. 2002;95:2346–2352. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werbajh S, Nojek I, Lanz R, Costas MA. RAC-3 is a NF-kappa B coactivator. Febs Lett. 2000;485:195–199. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D, Sham JS, Zeng WF, Lin HL, Bi J, Che LH, Hu L, Zeng YX, Guan XY. Correlation of AIB1 overexpression with advanced clinical stage of human colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu FP, Xie D, Wen JM, Wu HX, Liu YD, Bi J, Lv ZL, Zeng YX, Guan XY. SRC-3/AIB1 protein and gene amplification levels in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Lett. 2007;245:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JM, Liao L, Ning C, Yoshida-Komiya H, Deng CX, O'Malley BW. The steroid receptor coactivator SRC-3 (p/CIP/RAC3/AIB1/ACTR/TRAM-1) is required for normal growth, puberty, female reproductive function, and mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:6379–6384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120166297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Yu CT, Ozen M, Ittmann M, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. Steroid receptor coactivator-3 and activator protein-1 coordinately regulate the transcription of components of the insulin-like growth factor/AKT signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11039–11046. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying H, Furuya F, Willingham MC, Xu J, O'Malley BW, Cheng SY. Dual functions of the steroid hormone receptor coactivator 3 in modulating resistance to thyroid hormone. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7687–7695. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7687-7695.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Hashimoto Y, Kwak I, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. Role of the steroid receptor coactivator SRC-3 in cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7742–7755. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7742-7755.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HJ, Yan J, Luo WP, Ayala G, Lin SH, Erdem H, Ittmann M, Tsai SY, Tsai NJ. SRC-3 is required for prostate cancer cell proliferation and survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7976–7983. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou JX, Zhong Z, Shi XB, Tepper CG, deVere White RW, Kung HJ, Chen H. ACTR/AIB1/SRC-3 and androgen receptor control prostate cancer cell proliferation and tumour growth through direct control of cell cycle genes. Prostate. 2006;66:1474–1486. doi: 10.1002/pros.20477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]