Abstract

Objective

To investigate changes that took place between 2006 and 2010 in the inequity gap for antenatal care attendance and delivery at health facilities among women in Viet Nam.

Methods

Demographic, socioeconomic and obstetric data for women aged 15–49 years were extracted from Viet Nam’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey for 2006 (MICS3) and 2010–2011 (MICS4). Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine if antenatal care attendance and place of delivery were significantly associated with maternal education, maternal ethnicity (Kinh/Hoa versus other), household wealth and place of residence (urban versus rural). These independent variables correspond to the analytical framework of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health.

Findings

Large discrepancies between urban and rural populations were found in both MICS3 and MICS4. Although antenatal care attendance and health facility delivery rates improved substantially between surveys (from 86.3 to 92.1% and from 76.2 to 89.7%, respectively), inequities increased, especially along ethnic lines. The risk of not giving birth in a health facility increased significantly among ethnic minority women living in rural areas. In 2006 this risk was nearly five times higher than among women of Kinh/Hoa (majority) ethnicity (odds ratio, OR: 4.67; 95% confidence interval, CI: 2.94–7.43); in 2010–2011 it had become nearly 20 times higher (OR: 18.8; 95% CI: 8.96–39.2).

Conclusion

Inequity in maternal health care utilization has increased progressively in Viet Nam, primarily along ethnic lines, and vulnerable groups in the country are at risk of being left behind. Health-care decision-makers should target these groups through affirmative action and culturally sensitive interventions.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier les modifications du fossé des inégalités, survenues entre 2006 et 2010, en termes de fréquentation des soins prénatals et d'accouchement dans les établissements de santé, chez les femmes du Viet Nam.

Méthodes

Les données démographiques, socio-économiques et obstétriques des femmes âgées de 15 à 49 ans ont été extraites de l'Enquête en grappes à indicateurs multiples, effectuée au Viet Nam en 2006 (MICS3) et en 2010-2011 (MICS4). Une régression logistique multivariée a été effectuée pour déterminer si la fréquentation des soins prénatals et le lieu de l'accouchement étaient significativement associés au niveau d'éducation de la mère, à l'origine ethnique de la mère (Kinh/Hoa par rapport aux autres), à la richesse du foyer et au lieu de résidence (urbain ou rural). Ces variables indépendantes correspondent au cadre d'analyse de la Commission sur les déterminants sociaux de la santé.

Résultats

Des écarts importants entre les populations urbaines et rurales ont été constatés dans le MICS3 et dans le MICS4. Bien que la fréquentation des soins prénatals et les taux d'accouchement des établissements de santé se soient nettement améliorés entre les enquêtes (de 86,3 à 92,1% et de 76,2 à 89,7%, respectivement), les inégalités ont augmenté, en particulier entre les ethnies. Le risque de ne pas accoucher dans un établissement de santé a augmenté de façon significative chez les femmes issues des minorités ethniques des zones rurales. En 2006, ce risque était près de cinq fois plus élevé que chez les femmes de l'ethnie majoritaire Kinh/Hoa (rapport des cotes, RC: 4,67, intervalle de confiance IC à 95%: de 2,94 à 7,43); en 2010-2011, il a presque été multiplié par 20 (RC: 18,8; IC à 95%: de 8,96 à 39,2).

Conclusion

L'inégalité dans l'utilisation des soins de santé maternelle a augmenté progressivement au Viet Nam, principalement chez les ethnies, et les groupes vulnérables du pays risquent d'être laissés pour compte. Les décideurs des soins de santé devraient cibler ces groupes, en mettant en place une action positive et des interventions tenant compte de la culture.

Resumen

Objetivo

Investigar los cambios que tuvieron lugar entre 2006 y 2010 en la brecha de desigualdad respecto a la asistencia a cuidados prenatales y la prestación sanitaria en instalaciones sanitarias a mujeres de Viet Nam.

Métodos

Se obtuvieron datos demográficos, socio-económicos y obstétricos de mujeres de edades comprendidas entre los 15 y 49 años, a partir de la encuesta a base de indicadores múltiples de Viet Nam para los períodos 2006 (MICS3) y 2001-2011 (MICS4). Se realizó un análisis de regresión logística multivariada para determinar si la asistencia a cuidados prenatales y el lugar de prestación sanitaria estaban significativamente vinculados con la educación de la madre, la etnia materna (Kinh y Hoa frente a otras), los recursos familiares, así como el lugar de residencia (urbano frente a rural). Estas variables independientes corresponden al marco analítico de la Comisión sobre Determinantes Sociales de la Salud.

Resultados

Se hallaron grandes diferencias entre las poblaciones rurales y urbanas, tanto en MICS3 como en MICS4. Pese a que los índices de la asistencia a cuidados prenatales y de la tasa de partos en instalaciones sanitarias mejoraron substancialmente entre las encuestas (del 86,3 al 92.1% y del 76,2 al 89,7%, respectivamente), aumentaron las desigualdades, sobre todo en función del origen étnico. El riesgo de no dar a luz en un centro de salud aumentó significativamente entre las mujeres pertenecientes a minorías étnicas residentes en zonas rurales. En 2006, dicho riesgo era cinco veces mayor entre las mujeres de las etnias Kinh/Hoa (mayoría) (índice de probabilidad, IP: 4,67; 95% intervalo de confianza, IC: 2,94–7,43); en 2010-2011 llegó a ser casi 20 veces mayor (IP: 18,8; 95% IC: 8,96–39,2).

Conclusión

La desigualdad en la utilización de los servicios maternos ha aumentado progresivamente en Viet Nam, sobre todo, entre las distintas etnias. Asimismo, los grupos desfavorecidos del país están en riesgo de marginalidad. Las autoridades sanitarias deben orientarse hacia estos grupos por medio de acciones afirmativas, así como de intervenciones culturalmente sensibles.

ملخص

الغرض

تحري التغيرات التي حدثت في الفترة من 2006 إلى 2010 في فجوة عدم الإنصاف المعنية بالتردد على خدمات الرعاية السابقة للولادة وإيتائها في المرافق الصحية بين السيدات في فييت نام.

الطريقة

تم استخلاص البيانات الديمغرافية والاجتماعية والاقتصادية والتوليدية للسيدات اللاتي تتراوح أعمارهن من 15 إلى 49 سنة من الدراسة الاستقصائية الجماعية متعددة المؤشرات المعنية بفييت نام لعام 2006 (MICS3) والفترة من 2010 إلى 2011 (MICS4). وتم إجراء الارتداد اللوجيستي متعدد المتغيرات لتحديد ما إذا كان التردد على خدمات الرعاية السابقة للولادة وأماكن إيتاء هذه الخدمات مرتبطاً إلى حد كبير بتثقيف الأم والأصل العرقي للأم (كينه/هوا مقابل غيرها من الأعراق) وثروات الأسر ومحل الإقامة (الحضر في مقابل الريف). وتتوافق هذه المتغيرات المستقلة مع الإطار التحليلي للجنة المعنية بالمحددات الاجتماعية للصحة.

النتائج

تم العثور على تباينات كبيرة بين سكان المناطق الحضرية وسكان المناطق الريفية في كلتا الفترتين MICS3 وMICS4. وعلى الرغم من تحسن معدلات التردد على خدمات الرعاية السابقة للولادة وإيتاء المرافق الصحية إلى حد كبير بين الدراسات الاستقصائية (من 86.3 % إلى 92.1 % ومن 76.2 % إلى 89.7 %، على التوالي)، إلا أن عدم الإنصاف زاد، ولاسيما عبر الأصول العرقية. وزادت إلى حد كبير المخاطر الناجمة عن عدم الولادة في مرافق صحية بين سيدات الأقلية العرقية اللاتي يعشن في المناطق الريفية. وفي عام 2006، ازدادت هذه المخاطر خمس مرات تقريباً بين سيدات عرقية كينه/هوا (الأغلبية) (نسبة الاحتمال: 4.67؛ فاصل الثقة 95 %: من 2.94 إلى 7.43)؛ وفي الفترة من 2010 إلى 2011، أصبحت أعلى 20 مرة تقريباً (نسبة الاحتمال: 18.8؛ فاصل الثقة 95 %: من 8.96 إلى 39.2).

الاستنتاج

ازداد عدم الإنصاف في الاستفادة من خدمات الرعاية الصحية للأمهات تدريجياً في فييت نام، وبشكل رئيسي عبر الأصول العرقية، وتتعرض الفئات سريعة التأثر في البلد إلى مخاطر التخلف عن الركب. وينبغي أن يستهدف صناع القرار في مجال الرعاية الصحية هذه الفئات من خلال إجراءات إيجابية وتدخلات تراعي الثقافات على اختلافها.

摘要

目的

调查在2006 年至2010 年之间越南妇女产前保健就诊情况以及在卫生设施分娩的不平等差距方面发生的变化。

方法

从越南的2006(MICS3)和2010–2011(MICS4)多指标集群调查摘录15 至49 岁妇女的人口、社会经济和产科数据。执行多变量逻辑回归来确定产前保健就诊率和分娩地点是否与孕产妇教育、孕产妇种族(京族/华族与其他种族比较)、家庭财富和居住地点(城市和农村)明显相关。这些独立变量与健康社会决定因素委员会的分析框架相对应。

结果

在MICS3 和MICS4 中都发现了城市和农村人口之间存在很大差异。尽管两次调查之间产前保健就诊率和卫生设施分娩率大大改善(分别从86.3 上升到 92.1%,从76.2 上升到89.7%),但是不平等现象加剧,在种族方面尤其如此。农村地区少数民族妇女不在卫生设施中生育的风险大大增加。在2006 年,这种风险比京族/华族(多数民族)女性高近五倍(优势比,OR:4.67;95% 置信区间,CI:2.94–7.43);在2010–2011 期间,则高出将近20 倍(OR:18.8;95% CI:8.96–39.2)。

结论

越南孕产妇保健利用的不公平现象逐步增加,主要表现在种族之间,该国的弱势群体面临着被抛在后面的风险。针对这些群体,卫生保健决策者应该采取积极的行动和文化上敏感的干预措施。

Резюме

Цель

Исследовать изменения, которые произошли в период между 2006 и 2010 гг. в вопросе неравенства при получении женщинами услуг дородового ухода в учреждениях здравоохранения во Вьетнаме.

Методы

Демографические, социально-экономические и акушерские данные для женщин в возрасте 15-49 лет были взяты из кластерного обследования по многим показателям (MICS), проведенного во Вьетнаме в 2006 г. (MICS3) и 2010-2011 гг. (MICS4). В обследовании был использован метод многофакторной логистической регрессии с целью определить, насколько существенно зависит получение услуг дородового ухода и место родов от образования, этнической принадлежности матерей (кинь/хoa по сравнению с другими этносами), благосостояния семьи и места жительства (город или село). Эти независимые переменные соответствуют аналитической методике, используемой Комиссией по социальным детерминантам здоровья.

Результаты

В обоих кластерных обследованиях, MICS3 и MICS4, были обнаружены большие отличия в условиях оказания услуг для городского и сельского населения. Хотя качество дородового ухода и объем оказания этих услуг учреждениями здравоохранения существенно улучшились в период между обследованиями (с 86,3 до 92,1% и с 76,2 до 89,7%, соответственно), неравенство возросло, особенно по этническому признаку. Риск рождения ребенка не в медицинском учреждении значительно вырос среди женщин из этнических меньшинств, проживающих в сельской местности. В 2006 г. этот риск был почти в пять раз выше, чем среди женщин этнической принадлежности кинь/хоа (основные этносы) (отношение рисков, ОР: 4,67; 95% доверительный интервал, ДИ: 2,94–7,43); в 2010–2011 г. он был уже почти в 20 раз выше (ОР: 18,8; 95% ДИ: 8,96–39,2).

Вывод

Во Вьетнаме возросло неравенство в оказании услуг здравоохранения будущим матерям, в первую очередь, по этническому признаку. Кроме того, для уязвимых групп населения в данной стране существует рискуют не получить такие услуги. Лица, формирующие политику в области здравоохранения, должны направить усилия на оказание услуг этим группам посредством инициатив по обеспечению равноправия и учета культурных особенностей.

Introduction

Large disparities in health outcomes exist between countries and within them. These differences are largely defined and perpetuated by social structures and mediated by material and behavioural factors and by aspects of health-system delivery.1 These socially-determined and unjust differences, termed inequities, will pose a great challenge for policy-makers and health-care planners as the deadline for achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) approaches and the need to look beyond 2015 looms ahead.2 The MDGs have fuelled enormous efforts to improve public health and well-being throughout the world, but they inherently lack an equity perspective. Countries’ attempts to reach the MDGs at the national level may result in improved health for the more prosperous segments of society but can leave disadvantaged groups, such as ethnic minorities, the urban poor and migrant populations, in a worse situation than before.2 General public health interventions also tend to reach and benefit the more prosperous groups in society first. Thus, efforts to attain the MDGs, however commendable and necessary, tend to widen the inequity gap in health.3 The gap in health indicators within a society cannot be assessed by looking at aggregated data, which often conceal large and morally unjustifiable differences between the health of the social majority and of poor, marginalized minorities.4,5 For a full grasp of the vulnerable position of these groups, it is essential to look at subnational data, disaggregated along the structural determinants of inequity. However, insufficient and dysfunctional national and international reporting systems make this difficult to do. Health-care planners need to rely instead on estimates and data obtained through surveys, such as the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS),4,6 and even when survey data are available, they are rarely comprehensive or used by policy-makers.7

Maternal mortality has traditionally been used as an indicator of and a proxy for health system performance and quality because of the complex, multifaceted character of the interventions involved in skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care.8 Measuring maternal mortality is difficult because of underreporting in many societies and because different definitions are used.9 The fifth MDG, which sets targets for maternal health, involves not only indicators that measure maternal mortality, but also access to reproductive health services, including antenatal care and skilled birth attendance. These crucial components of the continuum of care for mother and child can be measured and used to assess the degree of inequity in health care delivery.

Viet Nam, a country with a growing economic and public sector, is going through an economic and demographic transition.10 Historically, the country has pursued the socialist goal of achieving universal health coverage. Hence, its health-care infrastructure covers a very large fraction of the population. Viet Nam has also set an example for the world in terms of mobilizing the population during health promotion campaigns. This was evident during tetanus eradication and Expanded Programme on Immunization activities.11 With a steady decline in maternal mortality, child mortality and malnutrition over the past decades, Viet Nam has also exceeded expectations for a middle-income country.12 However, evidence points to growing disparities in health outcomes and inequity in health has started to gain attention in recent years.5,13,14 The Vietnamese Ministry of Health has prioritized maternal and child health over the years and has made efforts to improve the health of mothers and children, but even in this area great inequities exist.15,16 In a previous paper we used data from the MICS3 survey conducted in 2006 to report on these differences in maternal health care utilization, particularly in antenatal care and skilled birth attendance.17 Data from MICS4, conducted in 2010–2011, is now available. The rapid social development that has taken place in Viet Nam in recent years makes it important to examine changes in the equity gap linked to antenatal care attendance and delivery in health facilities. The aim of this study is to examine these changes.

Methods

Data sources and sampling

The Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) was designed by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for the collection of internationally comparable data. The General Statistics Office in Viet Nam has conducted the MICS over the past decade. MICS3 covered 8356 households and 10 063 women aged 15–49 years. Response rates were nearly 100% for households and 94.1% for women, respectively. MICS4 covered 11 642 households and 12 115 women aged 15–49, and response rates were 99.8% for households and 96.3% for women, respectively. The surveys included three sets of questionnaires: (i) a household questionnaire used to collect information on the household, its members and dwelling characteristics; (ii) a questionnaire administered only to women of reproductive age (15–49 years) living in the household; and (iii) a questionnaire on children younger than 5 years living in the household, administered to mothers or caretakers. The English-language MICS questionnaires were translated into Vietnamese, pre-tested and subsequently modified and revised for the Vietnamese context. The questionnaire for women included modules for child mortality and maternal and neonatal health. The sampling method used has been reported in detail elsewhere.18,19 For this study, data from MICS3 and MICS4 were extracted and analysed with authorization from UNICEF.

Variables of interest

The dependent variables were antenatal care coverage and place of delivery, which are recognized as key determinants of maternal health and indicators of progress towards MDG5. For MICS, antenatal care coverage is defined as the percentage of women aged 15–49 years – among those who had a liveborn during the two years before the survey – who received antenatal care from skilled health personnel at least once. “Skilled personnel” includes accredited health professionals such as midwives, physicians and nurses, but not traditional birth attendants. Place of delivery is dichotomized as delivery in a health facility (private or public) or outside the health system (home delivery).

Inequity is commonly defined as an unjust difference between social groups attributable to socioeconomic determinants.1 For this study we used as independent variables the following structural determinants, which correspond to the framework proposed by the Commission on Social Determinants of Health: maternal education, mother’s ethnicity, household wealth and place of residence.1 To capture differences between the most disadvantaged groups and the general population, we dichotomized all independent variables. Ethnicity was defined on the basis of maternal lineage as either Kinh/Hoa or non-Kinh/Hoa. The Hoa are ethnically Chinese. Although they are the sixth largest minority group in Viet Nam, their living standards are on a par with those of the Kinh majority. Maternal education was defined as either having attended school or never having done so. Household economic status was determined by means of an asset and household economic status index developed using principal component analysis to calculate a wealth score. The assets considered were radio, television, mobile phone, telephone, refrigerator, bicycle, motorbike, car and boat. Household status was based on floor, roof and wall material, type of fuel used, number of rooms used for sleeping, availability of electricity and water and type of toilet facilities.18 Households that scored in the lowest quintile were considered poor and the rest, non-poor.

Data analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression to analyse effects and associations between maternal health care utilization and the structural determinants of interest. We stratified all structural determinants to detect changes over time in subgroups. We used Pearson’s χ2 tests to detect differences between groups, with a P-value of < 0.05 considered indicative of statistical significance. We performed statistical analyses with STATA version 12 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, United States of America).

Results

In total, 9473 women were interviewed for MICS3 and 11 663 for MICS4. In this study, we included women aged 15–49 years who had given birth two years before the interview. This resulted in a total sample of 2386 women. The mean age of the women was 27.6 and 27.4 years in MICS3 and MICS4, respectively (P = 0.41). Socioeconomic status differed significantly between the women interviewed in the two surveys (Table 1). MICS4 had a significantly larger proportion of women who were non-poor, had attended school and belonged to the ethnic majority. It also had a larger proportion of women from urban areas than MICS3. Maternal health care utilization differed between the two survey samples as well. A larger proportion of women had delivered in a facility and had attended antenatal care in MICS4 than in MICS3. The rate of home delivery rate dropped significantly, by more than 50%, between MICS3 and MICS4 (Table 1). However, despite an overall increase in maternal health care utilization, the rate of delivery at health facilities remained significantly higher among women from non-poor households (Fig. 1), which shows that the equity gap persisted. A comparison of antenatal care attendance among different household economic groups revealed similar findings (data not shown).

Table 1. Characteristics of mothers interviewed for Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) 3 and 4, Viet Nam, 2006 and 2010–2011 .

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 (MICS3) (n = 1023) | 2010–2011 (MICS4) (n = 1363) | ||

| Household economic quintile/status | |||

| Fiftha | 172 (16.8) | 305 (22.4) | – |

| Fourth | 195 (19.1) | 268 (19.7) | – |

| Third | 194 (19.0) | 240 (17.6) | – |

| Second | 178 (17.4) | 223 (16.4) | – |

| First | 284 (27.8) | 327(24.0) | 0.001 |

| 2nd to 5th quintiles | 739 (72.2) | 1036 (76.0) | – |

| Poorest quintile | 284 (27.8) | 327 (24.0) | 0.037 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Kinh/Hoa (majority) | 726 (71.0) | 1076 (78.9) | |

| Non-Kinh/Hoa (minority) | 297 (29.0) | 287 (21.1) | < 0.001 |

| Maternal education | |||

| Attended school | 906 (88.6) | 1273 (93.4) | – |

| Never attended school | 117 (11.4) | 90 (6.6) | < 0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Currently married | 995 (97.3) | 1342 (98.5) | – |

| Not married | 28 (2.7) | 21 (1.5) | 0.04 |

| Place of residence | |||

| Urban | 226 (22.1) | 542 (39.8) | – |

| Rural | 797 (77.9) | 821 (60.2) | < 0.001 |

| Maternal health care utilization | |||

| Skilled antenatal care at least once | |||

| Yes | 883 (86.3) | 1255 (92.1) | – |

| No | 140 (13.7) | 108 (7.9) | < 0.001 |

| Place of delivery | |||

| Health facility | 780 (76.2) | 1222 (89.7) | – |

| Home | 243 (23.8) | 141 (10.3) | < 0.001 |

a Wealthiest.

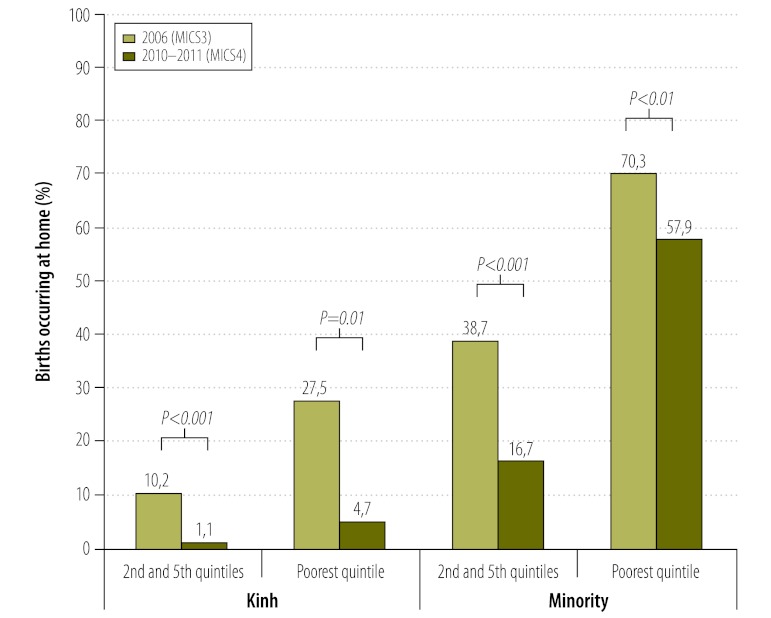

Fig. 1.

Equity gaps in delivery in health facilities, by maternal ethnicity and education and household economic status, Viet Nam, 2006 and 2010–2011

MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.

When data were stratified by place of residence, large disparities were noted between urban and rural areas. In both surveys, almost all women living in urban areas reported having received skilled antenatal care and having delivered at a health facility (Table 2). Thus, the changes in maternal health care utilization described previously took place entirely in the rural population and further analysis will focus on this subgroup.

Table 2. Maternal health care utilization, by place of residence, Viet Nam, 2006 and 2010–2011.

| Maternal health care utilization | No. (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban |

Rural |

||||||

| Yes | No | P | Yes | No | P | ||

| Skilled antenatal care | |||||||

| 2006 (MICS3) | 221 (97.8) | 5 (2.2) | – | 662 (83.1) | 135 (16.9) | – | |

| 2010–2011 (MICS4) | 531 (98.0) | 11 (2.0) | 0.87 | 724 (88.2) | 97 (11.8) | < 0.01 | |

| Health facility delivery | |||||||

| 2006 (MICS3) | 224 (99.1) | 2 (0.9) | – | 556 (69.8) | 241 (30.2) | – | |

| 2010–2011 (MICS4) | 532 (98.2) | 10 (1.8) | 0.33 | 690 (84.0) | 131 (16.0) | < 0.001 | |

MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.

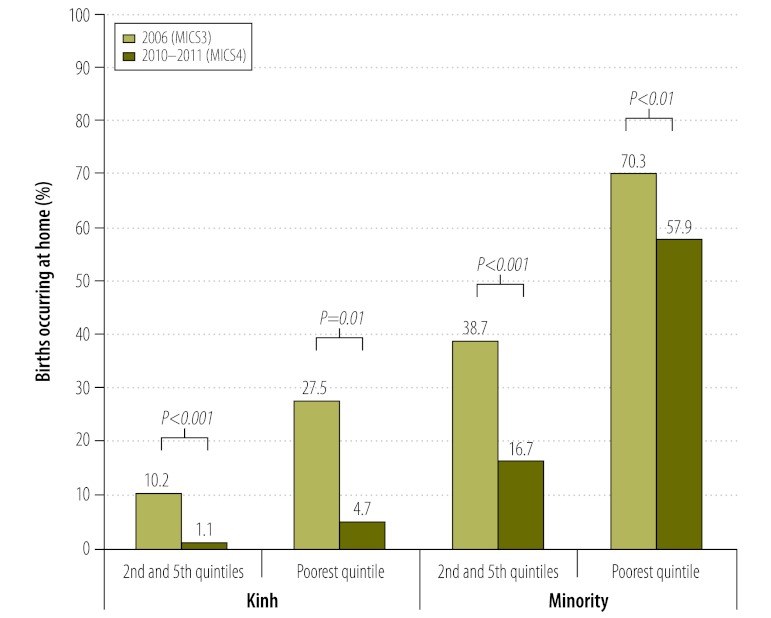

Among women in rural areas, the proportion of those who were poor was similar in the two surveys (34.3% and 36.8%, respectively; P = 0.29). However, the MICS4 sample had a slightly higher percentage of Kinh women (70.4% versus 64.4%; P < 0.01) than the MICS3 sample, as well as a higher percentage of women who had attended school (89.9% versus 85.6%; P < 0.01). In the sample of rural women, all socioeconomic variables – household economic status, maternal education and maternal ethnicity – were associated with maternal health care utilization in both surveys. Maternal age was not associated with antenatal care attendance or place of delivery in the univariate regression and was therefore excluded from the multivariate model. Table 3 shows the odds ratios (ORs) for absence of skilled antenatal care and home delivery among women in rural areas, by maternal and household characteristics. The elevated odds among poor women persisted across surveys and the OR for delivering at home for women belonging to ethnic minorities versus women of Kinh/Hoa ethnicity increased fourfold between MISC3 and MISC4 (Table 3). Although the rate of home delivery decreased among both Kinh/Hoa and non-Kinh/Hoa women, the drop was greatest in the first group (Fig. 2). Thus, inequity in this area has increased. Similar improvements between surveys were not found for antenatal care attendance, which improved significantly only among non-poor Kinh women in rural areas (Fig. 3).

Table 3. Results of multivariate regression showing change between MICS3 and MICS4 in the relative odds of maternal health care utilization in the rural population, by maternal and household socioeconomic indicators, Viet Nam, 2006 and 2010–2011.

| Maternal health care utilization | 2006 (MICS3) |

2010–2011 (MICS4) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No./n | OR (95% CI) | No./n | OR (95% CI) | ||

| No skilled antenatal care | |||||

| Household economic status | |||||

| 2nd to 5th quintiles | 34/524 | 1 | 10/519 | 1 | |

| Poorest quintile | 101/273 | 2.56 (1.43–4.57) | 87/302 | 4.54 (2.04–10.1) | |

| Maternal ethnicity | |||||

| Kinh/Hoa (majority) | 30/513 | 1 | 13/578 | 1 | |

| Non-Kinh/Hoa (minority) | 105/284 | 3.40 (1.88–6.16) | 84/243 | 5.39 (2.58–11.3) | |

| Maternal education | |||||

| Attended school | 75/682 | 1 | 44/738 | 1 | |

| Never attended school | 55/115 | 2.85 (1.73–4.71) | 30/83 | 7.03 (3.84–12.9) | |

| Home delivery | |||||

| Household economic status | |||||

| 2nd to 5th quintiles | 71/524 | 1 | 13/519 | 1 | |

| Poorest quintile | 170/273 | 2.84 (1.78–4.51) | 118/302 | 4.69 (2.34–9.39) | |

| Maternal ethnicity | |||||

| Kinh/Hoa (majority) | 61/513 | 1 | 10/578 | 1 | |

| Non-Kinh/Hoa (minority) | 180/284 | 4.67 (2.94–7.43)a | 121/243 | 18.8 (8.96–39.2)a | |

| Maternal education | |||||

| Attended school | 150/682 | 1 | 74/738 | 1 | |

| Never attended school | 91/115 | 3.48 (2.00–6.04) | 57/83 | 3.39 (1.85–6.21) | |

CI, confidence interval; MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; OR, odds ratio.

a Confidence intervals for MICS3 and MICS4 do not overlap.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of home deliveries among rural women, by ethnicity and household economic status, Viet Nam, 2006 and 2010–2011

MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.

Note: Pearson’s χ2 test was used to detect differences between groups.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of rural mothers who did not attend antenatal care during their most recent pregnancy, by ethnicity and household economic status. Viet Nam, 2006 and 2010–2011

MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; NS, not significant.

Note: Pearson’s χ2 test was used to detect differences between groups.

Discussion

This study has shown the persistence of inequities in maternal health care utilization in Viet Nam along socioeconomic and ethnic lines through a comparison of data on antenatal care attendance and health facility delivery from MICS3 (2006) and MICS4 (2010–2011). On the basis of the findings we conclude that the rate of delivery in health facilities has improved overall in the rural population, but that this improvement has been unevenly distributed among ethnic groups and women in different economic strata. Poor women belonging to ethnic minorities were less likely to deliver at home in 2010–2011 than in 2006, but rates of facility delivery improved more for non-poor women. Hence, the relative odds of delivering at home among poor, ethnic minority versus non-poor, Kinh/Hoa women increased significantly between MICS3 and MICS4. Antenatal care attendance also improved between MICS3 and MICS4, but the improvement was only statistically significant among non-poor, Kinh/Hoa women.

This study has limitations. Although more than 20 000 households were sampled in the two surveys combined, a fairly small sample of women was included in the analysis because those who had not had a liveborn in the two preceding years were excluded. This made it impossible to disaggregate data into subgroups for sub-analyses of maternal health care utilization in specific regions or among ethnic minority groups. Another limitation is that the sample may not be representative. For example, very few poor women from urban areas were included (11 in MICS3 and 25 in MICS4),18,19 perhaps because of an urban bias in the construction of the asset index20 or a skewed sampling procedure. In either case, the vulnerable situation of the urban poor, a particularly disadvantaged group, is not reflected. This group is likely to have less social capital than the rural poor because of social exclusion and isolation.21 Furthermore, the proportion of women belonging to ethnic minorities was slightly higher than the national average in both MICS3 and MICS4.

We analysed maternal health care utilization as a proxy for maternal mortality.22 In MICS3, the sisterhood method was used to calculate the maternal mortality ratio, which was 162 deaths per 100 000 live births.18 However, the necessary data for a similar estimation was not collected in MICS4.19 This is the reason that we resorted to using proxy indicators.

In MICS methodology, child mortality is calculated using the Brass estimation technique.23 This method provides point estimates with considerable variance and bias. Thus, it allows for the study of trends but makes direct comparisons between two time points quite undertain.23,24 In the final report for MICS4, the mortality rate among children less than 5 years of age whose mothers belonged to an ethnic minority was estimated at 39 deaths per 1000 live births by the Brass method.19 In the MICS3 survey, the corresponding rate was 35 deaths per 1000 live births.18 These figures, combined with decreased mortality among Kinh/Hoa children less than 5 years of age, point not only to greater inequity but also to increased child mortality among ethnic minorities. However, these data come from a relatively small sample and represent indirect measurements. Hence, any conclusions must be drawn with caution. From our findings it is more legitimate to conclude that inequity in maternal and child health has increased in Viet Nam, and that this also holds true for maternal and child mortality.

The dependent variables examined in this study, antenatal care coverage and delivery at health facilities, were maternal health care indicators collected in both MICS3 and MICS4. The World Health Organization recommends at least four antenatal care visits during pregnancy.25 The National Guidelines for Reproductive Health issued by Viet Nam’s Ministry of Health stipulate three or more antenatal care visits.26 The number of such visits was recorded in MICS4 but not in MICS3. Hence, we were unable to analyse this variable in our study. Skilled birth attendance is another indicator of maternal health care utilization commonly surveyed and analysed. This variable was collected in both MICS3 and MICS4 but showed a strong interaction with place of delivery. Only a very small number of women delivering at home did so in the presence of a skilled birth attendant. Furthermore, skilled attendance (or skilled care) at birth connotes delivery in an “enabling environment” with access to emergency obstetric care if required.27 We therefore felt that place of delivery was a more appropriate variable to include in the analysis.

The comparison of maternal care utilization between MICS3 and MICS4 also revealed some improvements worth mentioning. In the five years between surveys the rate of delivery at home was halved. This remarkable finding reflects the rapid economic transition occurring in Viet Nam at present. Infrastructural improvements and the growth of the middle class are driving the expansion and improvement of the health system and reducing geographical and economic barriers to health care, particularly for urban and non-poor rural residents.28,29 Nonetheless, our findings show that some vulnerable groups are being left behind and that the equity gap is widening. Conditions in Viet Nam differ from those that exist in nearby countries. In China, for example, large discrepancies exist between urban and rural populations in terms of maternal mortality, but there is no evidence that the equity gap is widening as a result of economic expansion.30,31 Thailand, on the other hand, has managed to close the equity gap in the provision of maternal care by adopting pro-poor policies and universal health coverage.32,33

In Viet Nam, maternal health care utilization between urban and rural areas shows striking differences. Large inequities exist along socioeconomic and ethnic lines. The causes and determinants of these inequities are manifold and diverse, as has been shown in several studies.29,34,35 Informal payments and a growing private sector, together with weak public health insurance, generate inequities because people’s ability to pay for services parallels the increasing income divide in society.34 Additionally, modernization has generated greater social complexity, with fewer opportunities for the less educated in society.35 According to our findings, in Viet Nam ethnic minorities are even more vulnerable than other disadvantaged groups during this time of economic transition. In addition to being less educated and poorer, ethnic minorities face cultural and linguistic barriers in accessing health care that are compounded by a lack of culturally sensitive programmes and interventions.36,37 Future efforts to reduce inequity in health, both in Viet Nam and globally, must be holistic; interventions targeting vulnerable groups must be designed not just on the basis of material wealth, but also ethnicity and education.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted within the Evidence for Policy and Implementation (EPI-4) project, established by leading Swedish health-oriented institutions to help conduct capacity-building towards evidence-informed decision-making on policies and interventions to improve the health of disadvantaged groups in relation to MDGs 4, 5 and 6 in China, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam.

Funding:

The Evidence for Policy and Implementation (EPI-4) project has been funded through a grant from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social determinants of health discussion paper 2 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.popline.org/node/216706 [accessed 31 January 2013].

- 2.Waage J, Banerji R, Campbell O, Chirwa E, Collender G, Dieltiens V, et al. The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015. Lancet. 2010;376:991–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61196-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victora CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA, Gwatkin D, Claeson M, Habicht JP. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet. 2003;362:233–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13917-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg RL, McClure EM. Disparities in interventions for child and maternal mortality. Lancet. 2012;379:1178–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60474-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barros AJ, Ronsmans C, Axelson H, Loaiza E, Bertoldi AD, Franca GV, et al. Equity in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in Countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet. 2012;379:1225–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byass P, Graham WJ. Grappling with uncertainties along the MDG trail. Lancet. 2011;378:1119–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friel S, Loring B, Aungkasuvapala N, Baum F, Blaiklock A, Chiang TL, et al. Policy approaches to address the social and environmental determinants of health inequity in Asia–Pacific. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012;24:896–914. doi: 10.1177/1010539512460569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T. Maternal mortality at the end of a decade: signs of progress? Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:561–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization & The World Bank. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank estimates Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chongsuvivatwong V, Phua KH, Yap MT, Pocock NS, Hashim JH, Chhem R, et al. Health and health-care systems in southeast Asia: diversity and transitions. Lancet. 2011;377:429–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61507-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Country social analysis – ethncity and development in Vietnam. Summary Report Washington: East Asia and Pacific Region, The World Bank; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acuin CS, Khor GL, Liabsuetrakul T, Achadi EL, Htay TT, Firestone R, et al. Maternal, neonatal, and child health in southeast Asia: towards greater regional collaboration. Lancet. 2011;377:516–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62049-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee for Ethnic Minority Affairs. Final report: analysis of the P135-II Baseline Survey. Hanoi: United Nations Development Programme; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowles JC, Bales S, Cuong LQ, Oanh TTM, Luon DH. Health equity in Viet Nam: a situation analysis focused on maternal and child mortality Ha Long: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Målqvist M, Nga NT, Eriksson L, Wallin L, Hoa DP, Persson LA. Ethnic inequity in neonatal survival: a case-referent study in northern Vietnam. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:340–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.02065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran TK, Nguyen CT, Nguyen HD, Eriksson B, Bondjers G, Gottvall K, et al. Urban–rural disparities in antenatal care utilization: a study of two cohorts of pregnant women in Vietnam. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:120. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goland E, Hoa DT, Målqvist M. Inequity in maternal health care utilization in Vietnam. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:24. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United Nations Children’s Fund. Monitoring the situation of children and women – Viet Nam multiple indicator cluster survey 2006, final report Hanoi: General Statistics Office; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.United Nations Children’s Fund. Monitoring the situation of children and women – Viet Nam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2011, final report Hanoi: General Statistics Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howe LD, Hargreaves JR, Huttly SR. Issues in the construction of wealth indices for the measurement of socio-economic position in low-income countries. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2008;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soeung SC, Grundy J, Sokhom H, Blanc DC, Thor R. The social determinants of health and health service access: an in depth study in four poor communities in Phnom Penh Cambodia. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yazbeck AS. Challenges in measuring maternal mortality. Lancet. 2007;370:1291–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Step-by-step guide to the estimation of child mortality. New York: United Nations Publications; 1990. Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/population/techcoop/DemEst/stepguide_childmort/stepguide_childmort.html [accessed 31 January 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewbank DC. The sources of error in Brass's method for estimating child survival: the case of Bangladesh. Popul Stud (Camb) 1982;36:459–74. doi: 10.1080/00324728.1982.10405598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villar J, Ba'aqeel H, Piaggio G, Lumbiganon P, Miguel Belizan J, Farnot U, et al. WHO antenatal care randomised trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. Lancet. 2001;357:1551–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04722-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National clinical guidelines on reproductive health care services Hanoi: Ministry of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussein J, Bell J, Nazzar A, Abbey M, Adjei S, Graham W. The skilled attendance index: proposal for a new measure of skilled attendance at delivery. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12:160–70. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leon DA. Cities, urbanization and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:4–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friel S, Chiang TL, Youngtae C, Yan G, Hashimoto H, Jayasinghe S, et al. Review article: freedom to lead a life we have reason to value? A spotlight on health inequity in the Asia Pacific region. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011;23:246–63. doi: 10.1177/1010539511402053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng XL, Zhu J, Zhang L, Song L, Hipgrave D, Guo S, et al. Socio-economic disparities in maternal mortality in China between 1996 and 2006. BJOG. 2010;117:1527–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanqiu G, Ronsmans C, Lin A. Time trends and regional differences in maternal mortality in China from 2000 to 2005. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:913–20. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prakongsai P, Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V. The equity impact of the universal coverage policy: lessons from Thailand. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 2009;21:57–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P. Equity in maternal and child health in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:420–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.068791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Målqvist M, Hoa DT, Thomsen S. Causes and determinants of inequity in maternal and child health in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:641. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cleland JG, Van Ginneken JK. Maternal education and child survival in developing countries: the search for pathways of influence. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:1357–68. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rheinländer T, Samuelsen H, Dalsgaard A, Konradsen F. Perspectives on child diarrhoea management and health service use among ethnic minority caregivers in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:690. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.An analysis of the situation of children in Dien Bien Dien Bien Provincial People's Committee & United Nations Children’s Fund; 2010. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/vietnam/resources_15554.html [accessed 31 January 2013]. [Google Scholar]