Graphical abstract

Highlights

► Identification and characterisation of Toxoplasma sphingolipid synthase (TgSLS). ► Demonstration of TgSLS inositol phosphorylceramide synthase activity. ► Identification of inositol phosphorylceramide in Toxoplasma extracts. ► Delineation of role of host sphingolipid biosynthesis in Toxoplasma proliferation. ► Host biosynthesis non-essential for proliferation, de novo synthesis could be key.

Abbreviations: PI, phosphatidylinositol; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; IPC, inositol phosphorylceramide; SM, sphingomyelin; CPE, ceramide phosphorylethanolamine; NBD, C6-ceramide-N-[6-[(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)amino]hexanoyl]-d-erythro-sphingosine; CHAPS, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; TgSLS, Toxoplasma gondii sphingolipid synthase; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblasts

Keywords: Toxoplasma, Sphingolipid, Inositol phosphorylceramide synthase, Host–parasite interaction

Abstract

Sphingolipids are essential components of eukaryotic cell membranes, particularly the plasma membrane, and are involved in a diverse array of signal transduction pathways. Mammals produce sphingomyelin (SM) as the primary complex sphingolipid via the well characterised SM synthase. In contrast yeast, plants and some protozoa utilise an evolutionarily related inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC) synthase to synthesise IPC. This activity has no mammalian equivalent and IPC synthase has been proposed as a target for anti-fungals and anti-protozoals. However, detailed knowledge of the sphingolipid biosynthetic pathway of the apicomplexan protozoan parasites was lacking. In this study bioinformatic analyses indicated a single copy orthologue of the putative SM synthase from the apicomplexan Plasmodium falciparum (the causative agent of malaria) was a bona fide sphingolipid synthase in the related model parasite, Toxoplasma gondii (TgSLS). Subsequently, TgSLS was indicated, by complementation of a mutant cell line, to be a functional orthologue of the yeast IPC synthase (AUR1p), demonstrating resistance to the well characterised AUR1p inhibitor aureobasidin A. In vitro, recombinant TgSLS exhibited IPC synthase activity and, for the first time, the presence of IPC was demonstrated in T. gondii lipid extracts by mass spectrometry. Furthermore, host sphingolipid biosynthesis was indicated to influence, but be non-essential for, T. gondii proliferation, suggesting that whilst scavenging does take place de novo sphingolipid synthesis may be important for parasitism.

1. Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate, intracellular protozoan parasite, which is able to invade and colonise a wide variety of nucleated vertebrate cells. It is a member of the Apicomplexa, a diverse phylum including important pathogens of humans and domestic animals such as Plasmodium (the causative agent of malaria), Cryptosporidium (diarrhoea), Eimeria (coccidiosis in poultry) and Theileria (East Coast Fever in cattle). Toxoplasma has emerged as an opportunistic pathogen and toxoplasmosis is an important disease in the immunocompromised, particularly AIDS patients, those receiving anti-cancer chemotherapy and organ transplant recipients [1]. Toxoplasma infection in utero is also a significant cause of congenital defects in humans [1] and spontaneous abortion in economically important domestic animals [2].

Sphingolipids are amphipathic lipids comprising sphingosine as the basic building unit. More complex sphingolipids consist of a sphingosine backbone N-acylated with a long-chain fatty acid (i.e. ceramide) and substituted with a head group moiety (e.g. sphingomyelin, glucosylceramide and ceramide-1-phosphate) [3]. Ceramide is a sphingolipid that functions as a secondary messenger in ubiquitous, evolutionarily conserved, signalling mechanisms [4]. Complex sphingolipids are major components of the outer leaflet of eukaryotic plasma membranes that are thought to be involved, together with sterols, in the formation of micro-domains known as lipid rafts. These rafts have been proposed to function in a diverse array of processes from the polarised trafficking of lipid-modified proteins, to the assembly and activation of signal transduction complexes [5]. In the apicomplexan Plasmodium species, sphingolipid-enriched lipid rafts have been implicated in the interaction of the parasite with the host erythrocyte through the trafficking of both host and parasite glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored proteins [6]. In addition, it has been demonstrated, by the incorporation of tritiated serine, that both Plasmodium falciparum and T. gondii synthesise sphingolipids de novo [7,8]. Like mammals, P. falciparum synthesises the complex phosphosphingolipid sphingomyelin (SM) [9–11] and an orthologue of the mammalian enzyme, SM synthase, has been identified from the genome database [12]. T. gondii has also been indicated to synthesise SM, although at relatively low levels compared to glycosphingolipids [8], and the presence of this species has subsequently been confirmed using mass spectrometry [13]. However, the enzyme responsible for any SM synthase activity has remained unidentified in T. gondii, and uncharacterised in any apicomplexan. Furthermore, it has also been reported that the parasites harbour relatively high quantities of ceramide phosphorylethanolamine (CPE), a non-abundant species in mammalian cells [13]. In addition, the synthesis of the non-mammalian phosphosphingolipid, inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC), has also been reported in T. gondii [14]. Importantly, the biosynthetic enzyme, IPC synthase, has been validated as a drug target in both the fungi and the kinetoplastid protozoa [15–18], and its inhibition by the anti-fungal aureobasidin A has been proposed in T. gondii [14].

Notably, in addition to de novo synthesis, intracellular parasites such as T. gondii may scavenge sphingolipids or their precursors from the host cell [19]. Indeed it has been suggested that the CPE (and SM) found in intracellular tachyzoites forms may result from the concentration of non-abundant host-derived lipid [13]. Within the host cell T. gondii resides within a specialised parasitophorous vacuole (PV) formed immediately after invasion and delineated by the PV membrane (PVM) [20]. Although the PV resists fusion with host organelles it does demonstrate an intimate, high affinity association with the ER and mitochondrion [21], the latter facilitating the scavenging of host lipoic acid [22]. Furthermore, recent work has indicated that host-derived lipid is the primary contributor to the intravacuolar network that fills the lumen of the PV [23]. Toxoplasma scavenges a variety of fatty acids and lipids from the host, including phospholipids and cholesterol, some of which are further metabolised by the parasite [24,25]. The mechanism of lipid scavenging is unclear, although current data argue against passive diffusion, acquisition on invasion [25] and (at least in the case of cholesterol) vesicular trafficking [24]. It has been proposed that the transport of cholesterol to the PV could be mediated via a protein carrier [24], and the possibility of direct inter-organelle transfer of lipids between the closely associated PVM and host ER and mitochondrial membranes has been evoked [22,25]. The balance between de novo synthesised and scavenged lipid is unclear, however when host phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels are restricted it is likely that the parasites scavenge choline and synthesise PC de novo [25].

To begin to understand the role of both de novo synthesis and scavenging of sphingolipid for T. gondii, we aimed to begin characterisation of the little understood parasite biosynthetic pathway and investigate the requirement, if any, for host sphingolipid. To these ends we herein report the identification and functional characterisation of a key enzyme in T. gondii sphingolipid synthesis that may represent a novel drug target and, in addition, show the delineation of the role of host biosynthesis in parasite proliferation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Selection, sequence analyses and cloning of candidate sphingolipid synthase

The T. gondii genome database (www.toxodb.org) was interrogated (Gish, 1996–2001) (http://blast.wustl.edu) with the two candidate sphingolipid synthase coding sequences previously identified from the genome database of the malaria parasite P. falciparum (plasmodb.org) [12]. A single sequence orthologue was identified, TgSLS accession number TGME49_046490, corresponding to the entry previously identified [13]. Sequence alignments were made using ClustalW [26] and phylogenetic analyses performed on the edited alignments using Maximum Parsimony, Protein Distance (PHYLIP Phylogeny Inference Package, version 3.5c) and Maximum Likelihood [27]. The candidate TgSLS open reading frame was amplified from genomic T. gondii DNA using Pfu polymerase (Promega) and the primer pair 5′TgSLSEcoRI (cgcgaattcATGCCCAGAACAGAGATG) and 3′TgSLS*HindIII (cccaagcttTTAGAGTCCCTCGATGGCGCGAACGAT). Cloning sites shown in lower case, with coding sequence in upper case. The product was purified, digested and cloned into the yeast expression vector pRS426MET25 creating pRS426 TgSLS.

2.2. Functional complementation of auxotrophic yeast AUR1 mutant

pRS426 TgSLS, together with pRS426 AUR1 and empty vector, were used to transform the YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1 Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain [28]. Transformants were selected on non-permissive SD-HIS-URA medium (0.17% Bacto yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% ammonium sulphate and 2% dextrose) or permissive SGR-HIS-URA medium (0.17% Bacto yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% ammonium sulphate, 4% galactose and 2% raffinose) containing the appropriate nutritional supplements at 30 °C.

2.3. In vitro assay of TgSLS activity

Microsomal membranes from exponentially growing YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1 pRS426 TgSLS or pRS426 AUR1 in SD-HIS-URA were prepared and the isolated membrane fraction re-suspended in storage buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2) with Complete® EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Applied Science) at a protein concentration of 10 mg/ml as described previously [18]. Microsomal membranes were subsequently washed in 40 mM CHAPS (4 °C, 60 min), isolated by centrifugation (150,000 × g, 4 °C and 100 min), re-suspended in storage buffer at 10 mg/ml and stored at −80 °C until use. The assay mix contained 1 mM donor substrate (bovine liver PI, PC or PE, Avanti Polar Lipids), 20 μg microsome prep, 100 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 6 mg/ml BSA and 5 μM NBD C6-ceramide [19]. Following incubation at 30 °C for 60 min the reaction was quenched by the addition of 150 μl of chloroform:methanol:water (10:10:3) and lipids separated and analysed as above. For inhibition experiments the reaction mix was pre-incubated for 30 min with appropriate quantities of aureobasidin A (Takara Bio Inc.) before the addition of NBD C6-ceramide.

2.4. Agar diffusion assay

YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1 complemented with TgSLS or AUR1 were assayed for susceptibility to aureobasidin A and myriocin (Sigma) as previously described [28]. Briefly, 2.4 OD600 units of logarithmically dividing cells were embedded in 15 ml of SD-HIS-URA with 0.8% agarose on 100 mm2 square Petri dishes (Sarstedt). Inhibitors were applied in DMSO at the concentrations indicated and the dishes incubated at 30 °C.

2.5. Mass spectrometry of T. gondii inositol phosphorylceramide

T. gondii (strain RH) were harvested from infected MEF host cells by passage through a 26 gauge needle and purified by separation on Sephadex-G25 columns (Amersham). Following PBS wash, the parasites were transferred to glass vials. Sphingolipid extracts were prepared as described [29] and analysed. The liquid chromatography-mass spectrometer consisted of a Waters Aquity UPLC system connected to a Waters LCT Premier orthogonal accelerated time of flight mass spectrometer (Waters, Millford, MA), operated in negative electrospray ionisation mode. Mass accuracy and reproducibility were maintained by using an independent reference spray by the LockSpray interference. The analytical column was a 100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 mm C8 Acquity UPLC BEH (Waters). The two mobile phases were A: methanol:water:formic acid (74:25:1); B: methanol:formic acid (99:1), both also contained 5 mM ammonium formate. A linear gradient was programmed as follows: 0.0 min: 80% B; 3 min: 90% B; 6 min: 90% B; 15 min: 99% B; 18 min: 99% B; 20 min: 80% B. The flow rate was 0.3 ml/min. Positive identification of all sphingolipid species was based on the accurate mass measurement with an error <5 ppm and their LC retention time.

2.6. Cell culture

T. gondii (strain RH, TATi-1; a kind gift from Prof Dominique Soldati-Favre, University of Geneva) were maintained in Vero cells grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Parasites were separated from host cell material by filtration through 3 and 5 μm polycarbonate filters (Millipore) after disruption by passage through a 26 gauge needle. Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO-K1) cells, the derived temperature sensitive serine palmitoyl transferase mutant SPB-1, plus SPB-1 complemented with cLCB-1 [30] were grown in Ham's F-12 media (Sigma–Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) at 37 °C or 33 °C (SPB-1 permissive temperature) with 5% CO2.

2.7. Suppression of host sphingolipid synthesis

For induction of the temperature-sensitive phenotype 105 cells were seeded into 24-well plates and incubated at 33 °C for 24 h. The medium was then replaced with Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS or, to form serum reduced media, 0.1% FBS, 1% Nutridoma-SP (Roche Applied Science), 250 μM oleic acid (Sigma Aldrich) and 5% fatty acid free Bovine Serum Albumen (BSA; Sigma Aldrich). The low-serum medium contains less than 1 μM sphingomyelin [31]. As indicated, myriocin (Sigma Aldrich) was added at this stage. Cells were then incubated at 39 °C for 72 h before T. gondii, purified as above, were added at a ratio of 2 parasites to 1 host cell and allowed to invade for 4 h. Subsequently, after washing with PBS, cells were incubated for a further 24 h in normal or serum reduced media before assay. Cell viability under these conditions was confirmed by staining with trypan blue (Sigma Aldrich).

2.8. Parasite invasion

T. gondii infected cells were fixed with methanol at −20 °C for 10 min, dried and stained with 300 nM DAPI in PBS for 5 min. Visualisation using an Olympus 1X-71 epifluorescent microscope allowed invasion to be scored.

2.9. Parasite proliferation

Following the 4 h invasion time, 1.0 μCi of [5,6-3H] uracil (GE Healthcare) was added per well and cultures incubated for 24 h. Supernatant was removed and cells then solublised with 250 μl of 1% (w/v) SDS containing 400 μg of unlabelled uracil/ml. 750 μl of 0.3 M TCA was then added and, after a 15 min incubation at 4 °C, precipitates were collected onto glass fibre filters in 96 well plates (Multiscreen HTS, Millipore) using a sampling manifold. The filters were washed twice with 0.3 M TCA and once with 95% ethanol, dried, placed in 10 ml of scintillation cocktail and the incorporated radioactivity then measured (Wallac 1450 MicroBeta TriLux, Perkin Elmer).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Identification of the T. gondii sphingolipid synthase

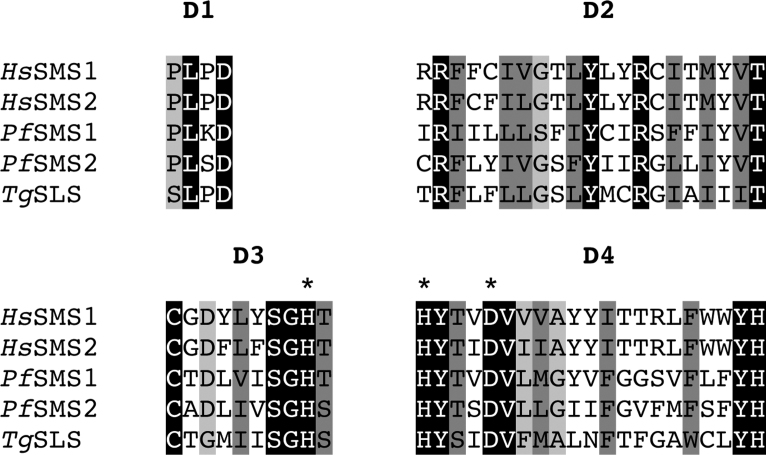

Although T. gondii has been demonstrated to synthesise complex sphingolipids de novo [7,8], the identity of the enzymes responsible for this have remained unclear. However, it has been shown, by incorporation of tritiated inositol, that T. gondii tachyzoites synthesise the non-mammalian, complex phosphosphingolipid, inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC) [14]. In addition, the synthesis of glycosphingolipids and sphingomyelin (SM), the predominant mammalian phosphospingolipid, have been similarly demonstrated [7,8]. Previous bioinformatic analyses have identified 2 orthologues of the mammalian SM synthase encoded by P. falciparum, PfSMS1 and 2 [12], an apicomplexan known to synthesise this sphingolipid species [9], and a single putative orthologue in the T. gondii genome [13]. This T. gondii predicted protein demonstrated only 28% and 27% identity to PfSMS1 and 2 respectively. However, further analyses of the predicted amino acid sequence identified the canonical SM synthase domains (D1-4) [12] (Fig. 1), strongly suggesting that this predicted protein is evolutionarily and functionally related to this class of enzymes. Phylogenetic analyses using the Maximum Parsimony algorithm (PHYLIP Phylogeny Inference Package, version 3.5c), of aligned amino acid sequence (TgSLS amino acids 92–362) including the active site residues defined by D3 and D4, supported this hypothesis and indicated that the apicomplexan sphingolipid (SL) synthases form a new group in a wider enzyme family that includes both SM and IPC synthases (Figure S1) [32]. However, further analyses using Maximum Likelihood and Protein Distance (PHYLIP) algorithms (data not shown) failed to support this result demonstrating the surprising divergence of TgSLS with respect to the other sphingolipid synthases, including PfSMS1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Identification of a candidate sphingolipid synthase from Toxoplasma gondii (TgSLS). Protein sequence alignment of D1, D2, D3 and D4 from HsSMS1 and 2, PfSMS1 and 2 and TgSLS. The positions highlighted in black are fully conserved; those in dark grey show conservation of strongly similar groups; those in light grey show conservation of weakly similar groups. The 3 residues of the predicted catalytic triad within D3 and D4 are designated by *.

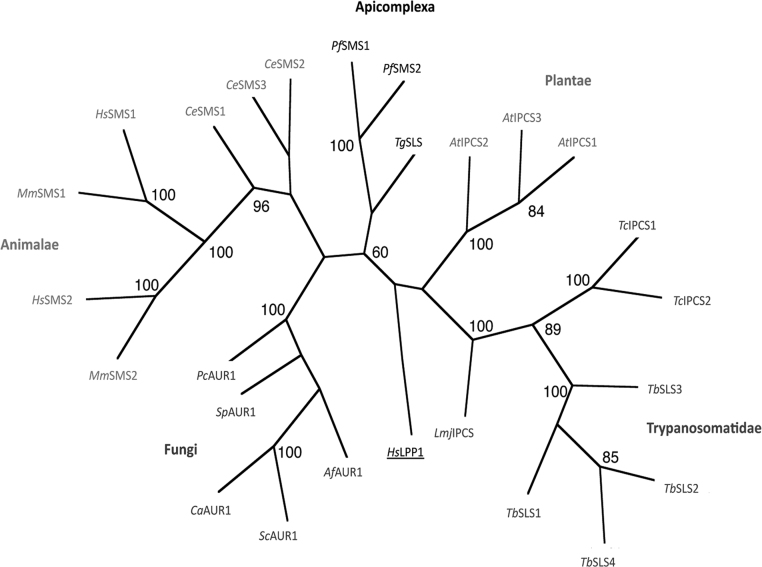

Supplementary Figure 1.

Maximum parsimony analyses of Animalae, Fungi, Trypanosomatidae, Plantae and Apicomplexa sphingolipid synthase predicted amino acid sequences. Bootstrap scores >60 indicated. Homo sapiens LPP1 (outgroup) accession number: O14494; T. gondii SLS: TGME49_046490; P. falciparum SMS1&2: PFF1210w and PFF1215w; Arabidopsis thaliana IPCS1-3: At3g54020.1, At2g37940.1, At2g29525.1; T. brucei SLS1-4: Tb09.211.1030, Tb09.211.1020, Tb09.211.1010, Tb09.211.1000; T. cruzi IPCS1&2: Tc00.1047053506885.124, Tc00.1047053510729.290; L. major IPCS: LmjF35.4990; Aspergillus fumigatus AUR1p: AAD22750; Candida albicans AUR1p: AAB67233; Pneumocystis carinii AUR1p: CAH17867; Saccharomyces cerevisiae AUR1p: NP_012922; Schizosaccharomyces pombe AUR1p: Q10142; Caenorhabditis elegans SMS1-3: Q9U3D4, AAA82341, AAK84597; Homo sapiens SMS1&2: AB154421, Q8NHU3; Mus musculus SMS1&2: Q8VCQ6, Q9D4B1.

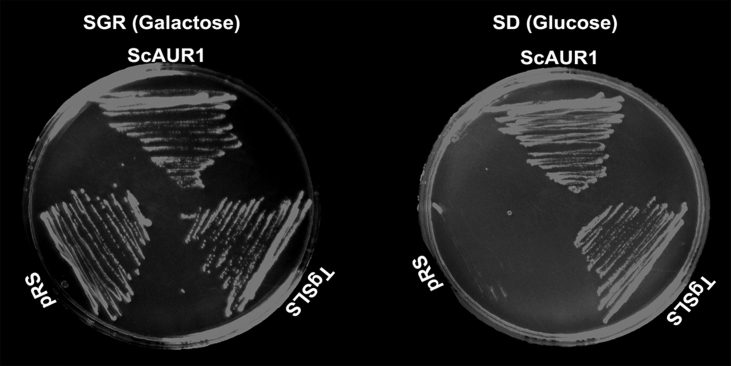

No functional analyses of these apicomplexan enzymes has previously been undertaken. Therefore, the open reading frame of the putative Toxoplasma SL synthase (TgSLS) was cloned into an URA3 selectable expression vector creating pRS426 TgSLS. Ectopic expression from this vector was subsequently demonstrated to restore the grow of YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1, the previously constructed AUR1 auxotrophic mutant [27], in non-permissive glucose containing media (Fig. 2). These data indicated that TgSLS is a functional orthologue of the yeast IPC synthase, AUR1p [33].

Fig. 2.

TgSLS complements a yeast AUR1p auxotrophic mutant. The growth of YPH499 HIS-GAL-AUR1 transformed with pRS426 TgSLS, a positive control (pRS426 ScAUR1) and a negative control (empty pRS426, pRS) was supported on permissive SGR media (galactose as carbon source). In contrast, only pRS426 TgSLS and the positive control could grow on non-permissive SD media (glucose as carbon source).

3.2. The functionality of the T. gondii sphingolipid synthase

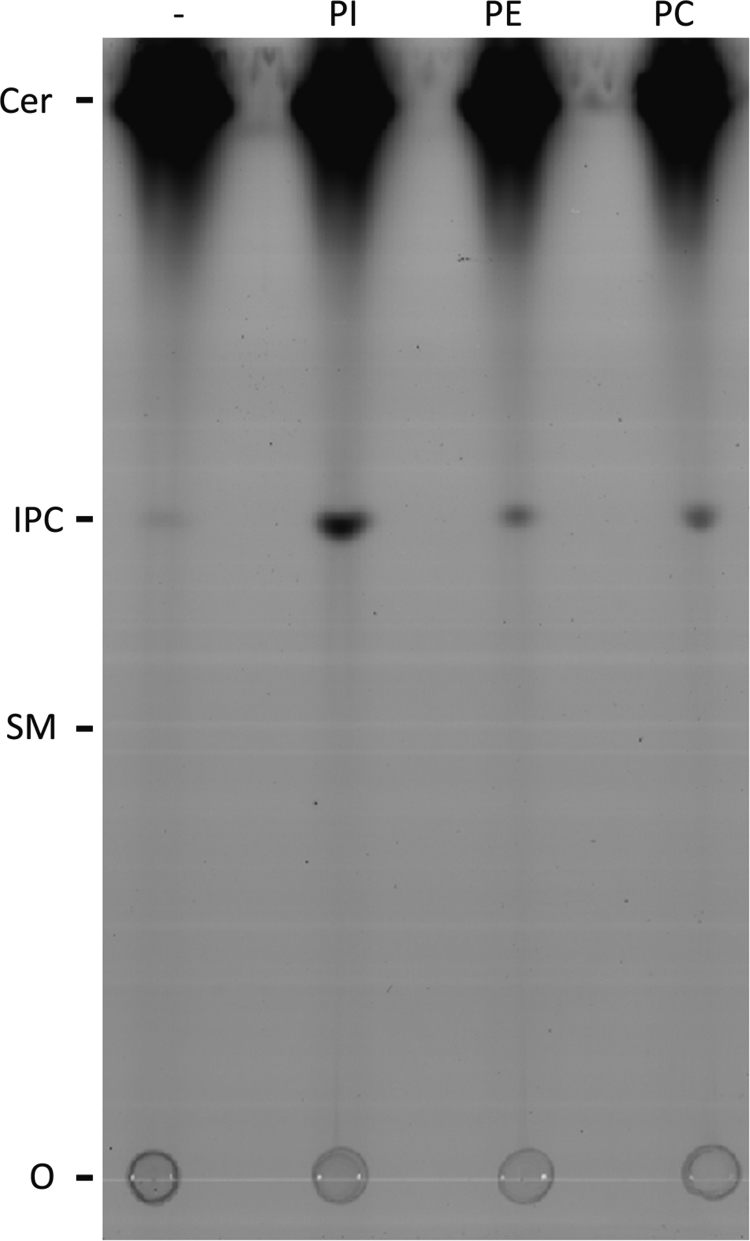

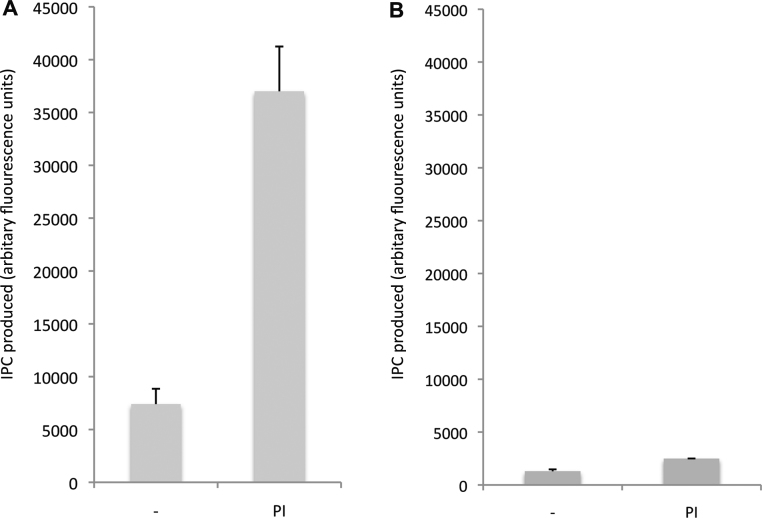

Given the evidence that Toxoplasma synthesise SM [7], IPC [14] and, perhaps, CPE [13] it was necessary to ascertain the functionality of TgSLS. To this end, microsomes were prepared from YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1 pRS426 TgSLS and formatted into an in vitro assay as previously described for other enzymes of this class [17,18,32]. The detergent wash in the preparation of the microsomes in this process removes lipids and therefore renders the enzyme largely dependent on the addition of exogenous substrate, the labelled acceptor substrate NBD-C6-ceramide and the donor substrate, phosphatidylinositol (for IPC synthesis) or phosphatidylcholine (for SM) [17]. TgSLS clearly synthesises a product migrating with IPC on the addition of exogenous PI, but no evidence for the utilisation of PC for SM synthesis or phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) for CPE synthesis was seen under the conditions employed (Fig. 3). The Toxoplasma enzyme clearly functions as an IPC synthase, an activity that is increased approximately 5-fold on the addition of the donor substrate PI to the assay (Figure S2A). There was also a small increase in IPC signal on the addition of both PC and PE. This small effect was consistent across four repeats and could be due to these lipids altering the composition of the micelles formed after the CHAPS wash, perhaps leading to increased availability of the remaining endogenous PI. In contrast, the yeast IPC synthase, AUR1p, is non-responsive to the mammalian PI employed in this assay system (Figure S2B) [18].

Fig. 3.

TgSLS functions as an inositol phosphorylceramide synthase. HPTLC fractionation of lipids after reaction of CHAPS-washed TgSLS extract with acceptor substrate NBD-C6-ceramide and either no donor substrate (−) or phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) or phosphatidylcholine (PC). Only the addition of PI led to a significant increase in the product formation, a species migrating with inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC). A representative image, O was the origin, ceramide (Cer) migrated at the front, markers from extracts of NBD-C6-ceramide labelled yeast (NBD-IPC) and mammalian Vero cells (NBD-SM).

Supplementary Figure 2.

(A) In vitro assay of TgSLS with no donor substrate (−) or PI demonstrated that IPC synthase activity was increased approximately 5-fold in the presence of this donor substrate; (B) In contrast, in an equivalent assay ScAUR1 was non-responsive with the bovine PI utilised. AFU – arbitrary fluorescence units. Mean of 3 independent experiments, standard deviation indicated.

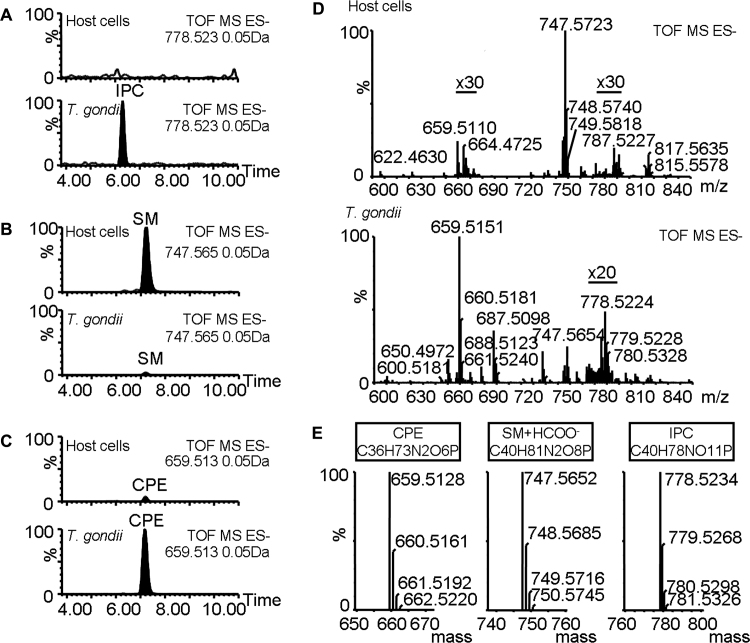

3.3. Inositol phosphorylceramide in T. gondii

Lipidomic analyses have identified the presence of SM, CPE, but not IPC in Toxoplasma [13]. Therefore, in order to investigate whether the parasite harbours this non-mammalian sphingolipid species analyses by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) [34] of lipids extracted from isolated T. gondii and host mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were performed (Fig. 4). The unambiguous identification of IPC was achieved by accurate mass determination by high resolution time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometry. A selected negative ion UPLC–TOF chromatogram, corresponding to the deprotonated C16-IPC species, of the T. gondii lipid extract exhibited a peak absent in the mammalian host cells (Fig. 4A). In contrast, selected negative ions corresponding to the formic acid adduct of SM (Fig. 4B) and deprotonated CPE (Fig. 4C) were detected in both host and parasite extracts, with CPE appearing enriched in T. gondii as previously recorded [13]. The mass spectrum of these peaks (Fig. 4D) showed an accurate mass measurement with errors with respect to the theoretical spectra (Fig. 4E), of 0.3 ppm and 3.5 ppm for SM and CPE, and 0.6 ppm for IPC. In addition, they demonstrated very similar isotopic patterns. These data demonstrate, for the first time, the presence of non-mammalian IPC (C18:1/C16:0) in T. gondii and strongly suggest that the IPC synthase activity of TgSLS seen in vitro above is also evident in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Inositol phosphorylceramide identification in Toxoplasma gondii lipid extracts. (A) Selected negative ion m/z 778.5234 (inositol phosphorylceramide, N-hexadecanoyl (N-C16) species, IPC); (B) selected negative ion m/z 747.5652 (sphingomyelin, N-hexadecanoyl (N-C16) species, SM); and (C) selected negative ion m/z 659.5128 (ceramide phosphorylethanolamine, N-hexadecanoyl (N-C16) species, CPE) UPLC–TOF chromatograms of mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) host cells and T. gondii lipid extracts. (D) Partial mass spectra (from 590 to 850 amu) corresponding to the 6 and 7.8 min range of a representative chromatogram obtained by UPLC/TOF-ESI(−) analysis of lipid extracts of host cells and T. gondii. Regions amplified (20× or 30×) as indicated. (E) Theoretical mass spectral pattern for the molecular ion region showing an (M–H)-ion for CPE and IPC and (M + HCOO−) for SM. CPE and SM were found in both samples, whereas IPC was only identified in T. gondii extracts.

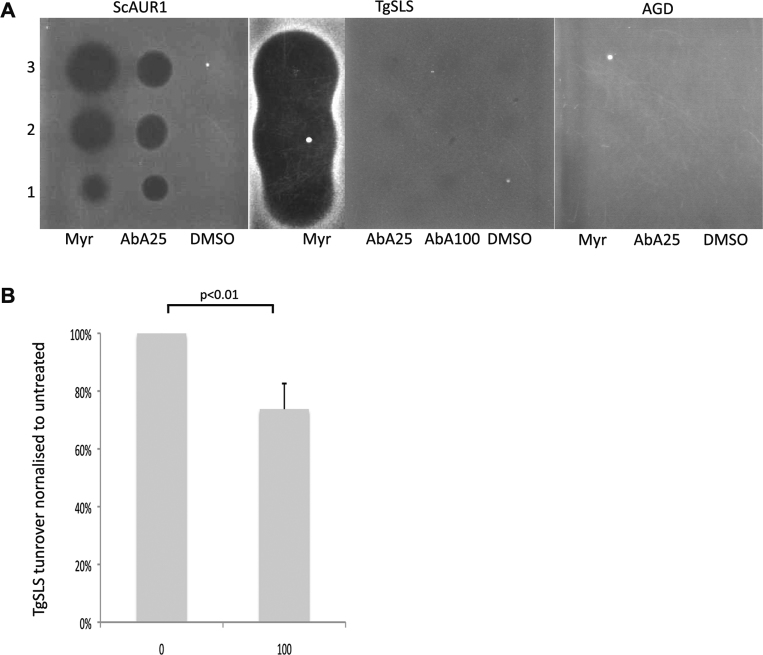

3.4. Inositol phosphorylceramide synthase as a drug target in T. gondii

The, then uncharacterised, Toxoplasma IPC synthase activity has previously been proposed as a drug target based on the efficacy of the potent, well-characterised fungal IPC synthase inhibitor aureobasidin A (AbA) against T. gondii within infected host cells [14]. To test this hypothesis we chose to analyse the sensitivity of YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1 pRS426 TgSLS to AbA by diffusion assay (Fig. 5A). AbA sensitive YPH499-HIS-GAL-AUR1 pRS426 AUR1 was used as a positive control and the sphingolipid bypass mutant AGD as a negative control. AGD is able to grow without synthesising sphingolipids and therefore is able to tolerate loss-of-function mutations in both serine palmitoyltransferase and IPC synthase [33]. These results demonstrated that TgSLS (the Toxoplasma IPC synthase) conferred AbA resistance to the yeast. The hyper-sensitivity to myriocin (an inhibitor of an upstream step in sphingolipid biosynthesis mediated by serine palmitoyltransferase) resembled that seen in the same mutant yeast complemented by the Leishmania major IPC synthase [28]. The reasons for this are unknown but perhaps reflect a sub-optimum functionality of the protozoan sphingolipid synthases in the yeast making the complemented lines more sensitive to upstream inhibition of sphingolipid biosynthesis.

Fig. 5.

TgSLS sensitivity to a verified yeast AUR1p inhibitor. (A) Agar diffusion assay of YPH499 HIS-GAL-AUR1 complemented yeast showed that, as expected, ScAUR1 complemented yeast were sensitive to myriocin at 1 mM (Myr) and aureobasidin A at 25 μM (AbA25). In contrast, TgSLS complemented yeast were resistant to AbA at 25 μM and 100 μM (AbA100), but hyper-sensitive to myriocin (1 mM) as evidenced by large zones of exclusion. AGD, the sphingolipid bypass mutant yeast lacking functional SPT and AUR1, acted as the negative control. DMSO was the vehicle control. (B) In vitro assay of the inhibitory effect of aureobasidin A (AbA) on TgSLS demonstrated that the Toxoplasma enzyme is only marginally, but significantly (p < 0.01), sensitive to the drug at a high concentration (100 μM). Fluorescence intensity of IPC was established following fractionation by HPTLC and normalised with respect to an untreated control. Mean of 3 independent experiments, standard deviation indicated.

To further investigate any inhibition of Toxoplasma IPC synthase activity by AbA the microsomal assay described above was employed (Fig. 5B). Small, but statistically significant, inhibition of enzyme turnover was noted at 100 μM. However, in contrast it should be noted that the aureobasidin A is a tight binding inhibitor of the yeast IPC synthase (AUR1p) with a reported IC50 of 0.2 nM [33]. Together, these data demonstrate that TgSLS is largely resistant to AbA and, as such, resembles the characterised, AbA-resistant IPC synthase from the kinetoplastid protozoan parasite, L. major [28].

Therefore, TgSLS is not the target for aureobasidin A in T. gondii and the previously reported efficacy [14] may be due to unidentified off target host effects as hypothesised for the kinetoplastid protozoa T. cruzi [35].

3.5. The role of host sphingolipid biosynthesis in T. gondii proliferation

As demonstrated above and previously [7] T. gondii have the ability to synthesise sphingolipids de novo. However, as an intracellular parasite T. gondii may also utilise host sphingolipids. In order to unravel the roles of host synthesis in parasite proliferation, Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells with a temperature sensitive serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) were utilised as host cells [30,31]. SPT is the first and rate-limiting enzyme in eukaryotic sphingolipid biosynthesis and in this cell line, SPB-1, the LCB1 subunit of this heterodimeric enzyme is thermolabile. At the non-permissive temperature virtually no SPT activity is detectable and sphingolipids are depleted when the SPB-1 cells are grown with minimal sera [36]. This phenotype is reversed by stable transfection of cDNA encoding cLCB1 [36]. Like T. gondii, the bacterial pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis (the causative agent of trachoma) resides within a non-fusagenic inclusion. Within SPB-1 cells C. trachomatis are completely unable to replicate at the non-permissive temperature, demonstrating that host sphingolipid biosynthesis is essential for intracellular growth of this pathogen [37] which acquires newly synthesised SM via the host exocytic pathway [38–41].

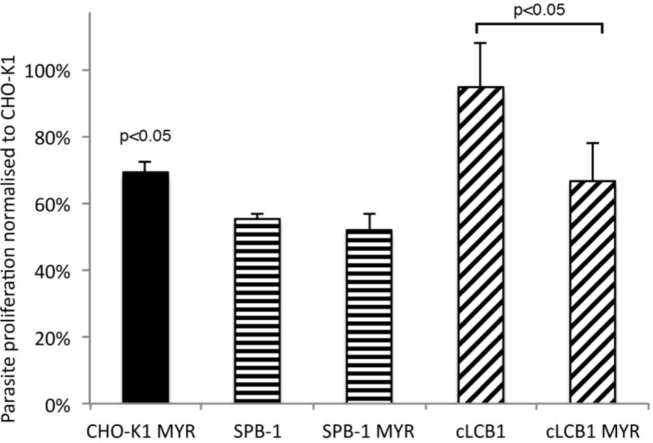

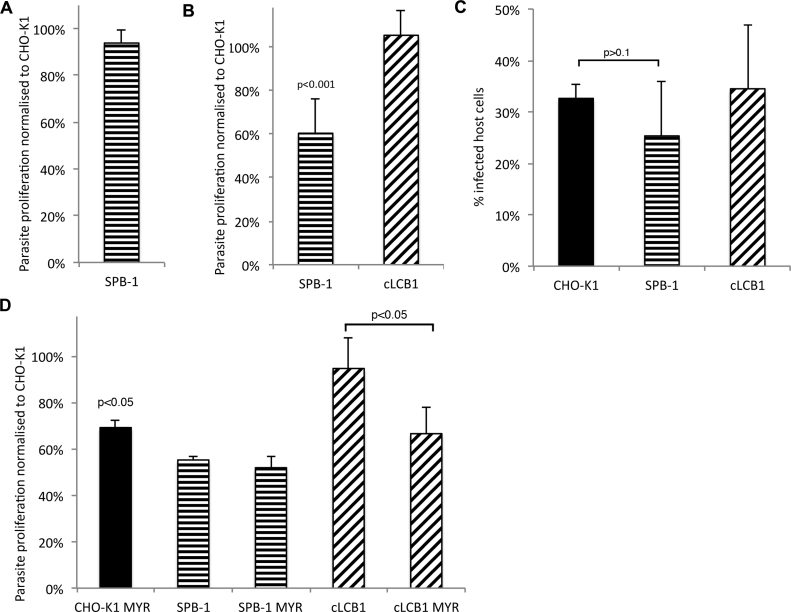

Utilising the same conditions employed in study of C. trachomatis replication [37], the proliferation of T. gondii in SPB-1 CHO cells was investigated. Briefly, before invasion host cells (both SPB-1 and controls) were incubated for 72 h at the non-permissive temperature (39 °C) in either complete or serum-reduced media. In the same media the cells were infected with isolated T. gondii as described in Section 2, and proliferation established by measuring [3H]-uracil incorporation as previously described [42] (Fig. 6A and B). It was clear that under the non-permissive conditions but in complete media the parasites replicated as well in the SPT deficient SPB-1 cells as they did in the wild type parental line (Fig. 6A). In contrast, with serum-reduced media T. gondii proliferation in the ts mutant cells was significantly reduced compared with the wild type control (p < 0.001; Fig. 6B). Notably, this effect was rescued in SPB-1 cells complemented by the expression LCB1 from stably transfected cDNA. Furthermore, these results are not due to differential T. gondii invasion as, under these conditions, there was no significant difference (p > 0.1) in the invasion rate between any of the cell lines employed (Fig. 6C). SPT can also be specifically inhibited by the natural product sphingosine analogue, myriocin [43]. Importantly, this induced a similar decrease in T. gondii proliferation in wild type CHO cells to that seen in the SPB-1 mutant. No effect was observed on treatment of the SPB-1 cells in which SPT activity was already suppressed, indicating that the effect seen in wild type cells was due to inhibition of host SPT and not the uncharacterised parasite orthologue (Fig. 6D). This may be due to the Toxoplasma SPT being either resistant or inaccessible to myriocin. Alternatively modulation of parasite SPT activity may have only a limited effect on proliferation. However, whilst host sphingolipid biosynthesis clearly plays a role in parasite replication, unlike for the bacterium C. trachomatis [37], it is non-essential. Furthermore, the addition of serum to the media negated any effect, indicating that scavenging from the extracellular milieu can compensate for the lack of host SPT activity. Notably, previous studies of T. gondii development within enucleated cells did not record any significant differences in parasite growth compared to nucleated controls [44]. Taken together these results indicate that host synthesis is not immediately critical for the ability of the parasite to grow, although prolonged depletion of sphingolipids (both synthesised and exogenous for 96 h) does influence proliferation (an approximate 40% reduction). This contrasts with the intra-cellular kinetoplastid, protozoan parasite Leishmania mexicana where suppression of host sphingolipid synthesis and depletion of extracellular lipid showed no effect on parasite proliferation [45].

Fig. 6.

Analyses of the role of host serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) in Toxoplasma gondii proliferation and invasion. Cells were cultured in 10% FCS (A) or in serum-reduced media (B) at the non-permissive temperature (39 °C). In the presence of complete media, T. gondii proliferation was the same in wild type (CHO-K1) and SPT-compromised (SPB-1) host cells (A). However, in serum-reduced media proliferation was significantly (p < 0.001) decreased in SPB-1 cells compared to the control (CHO-K1 and SPB-1 cLCB1) lines (B). All results normalised with respect to proliferation in parental CHO-K1 cells. Analyses of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate, standard deviation indicated. This effect was not due to significant differential invasion of the host cell lines (p > 0.1; C). Analyses of 3 independent experiments, standard deviation indicated. To analyse the effect of chemical inhibition of SPT, cells were cultured in serum-reduced media at the non-permissive temperature (39 °C) in the presence or absence of the inhibitor, myriocin (D). Myriocin treatment reduced Toxoplasma proliferation (p < 0.05) in wild type (CHO-K1) cells to similar levels to those seen in untreated SPT-compromised (SPB-1) host cells. The compound had no effect on proliferation in SPB-1 cells but exerted a similar effect to wild type in complemented mutant cells (SPB-cLCB1; p < 0.05). All results normalised with respect to proliferation in parental CHO-K1 cells. Analyses of experiments performed in triplicate, standard deviation indicated.

4. Conclusion

T. gondii is an important cause of disease in humans and domestic animals and a model apicomplexan pathogen [46]. The essential, eukaryotic sphingolipids have been implicated in the interaction of the related apicomplexan P. falciparum with its anucleate host cell, the erythrocyte [6]. In this study we utilised the ability of T. gondii to invade and colonise a wide range of nucleated vertebrate cells to examine the role host sphingolipid synthesis in invasion and proliferation. Genetic and chemical inhibition of the host pathway, coupled with depletion of media lipid, inhibited parasite proliferation (but not invasion). However, in contrast to the bacterium C. trachomatis [37], T. gondii was still able to replicate under these conditions. Notably, while auxotrophic for sterols [24], T. gondii have maintained the ability to synthesise sphingolipids de novo [7]. It could be hypothesised that this allows the parasite to survive and replicate in conditions of greatly reduced host sphingolipid biosynthesis. However, the protozoan biosynthetic pathway and the identity of the enzymes that constitute it remained relatively uninvestigated. In this study we showed that the identified T. gondii SL synthase demonstrated IPC synthase activity in vitro, and that this non-mammalian lipid species is detectable by mass spectrometry in parasite extracts. Given the status of the fungal AUR1p and kinetoplastid IPC synthases as promising drug targets [3], the identification of the T. gondii orthologue opens up the possibility of targeting this enzyme with novel anti-protozoals. However, the ability of the parasite to scavenge sphingolipid from the host may complicate the viability of TgSLS as a pharmaceutical target and clearly the balance between de novo synthesis and scavenging merits further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Gemma Fabrias (RUBAM) and Diane Lincoln (Durham University) for technical support, and Dr. Ehmke Pohl (Durham) for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Prof. Dominique Soldati-Favre (University of Geneva) for providing the T. gondii strain.

This work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Research Council (BB/D52396X/1) and Royal Society (2005/R1) grants to P.W.D. and a British Council/Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst Academic Research Collaboration Award to P.W.D. and R.T.S., J.G.M. and N.K.W.K. were funded by the Overseas Research Student Award Scheme. This work was also supported in part by a Wolfson Research Institute Small Grant Award to P.W.D., Grant-in-aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to K.H.) and Generalitat de Catalunya (J.C., Grant 2009 SGR 1072).

References

- 1.Chowdhury M.N. Toxoplasmosis: a review. Journal of Medicine. 1986;17:373–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubey J.P. Toxoplasma, Hammondia, Besnotia, Sarcocystis, and other cyst-forming coccidia of man and animals. In: Kreier J.P., editor. Parasitic protozoa. Academic Press; New York: 1977. pp. 101–237. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young S.A., Mina J.G., Denny P.W., Smith T.K. Sphingolipid and ceramide homeostasis: potential therapeutic targets. Biochemistry Research International. 2012;2012:248135. doi: 10.1155/2012/248135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith W.L., Merrill A.H., Jr. Sphingolipid metabolism and signaling minireview series. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:25841–25842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons K., Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haldar K., Mohandas N., Samuel B.U., Harrison T., Hiller N.L., Akompong T. Protein and lipid trafficking induced in erythrocytes infected by malaria parasites. Cellular Microbiology. 2002;4:383–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azzouz N., Rauscher B., Gerold P., Cesbron-Delauw M.F., Dubremetz J.F., Schwarz R.T. Evidence for de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis in Toxoplasma gondii. International Journal for Parasitology. 2002;32:677–684. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerold P., Schwarz R.T. Biosynthesis of glycosphingolipids de-novo by the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2001;112:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansorge I., Jeckel D., Wieland F., Lingelbach K. Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes utilize a synthetic truncated ceramide precursor for synthesis and secretion of truncated sphingomyelin. Biochemical Journal. 1995;308:335–341. doi: 10.1042/bj3080335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elmendorf H.G., Haldar K. Plasmodium falciparum exports the Golgi marker sphingomyelin synthase into a tubovesicular network in the cytoplasm of mature erythrocytes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1994;124:449–462. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haldar K., Uyetake L., Ghori N., Elmendorf H.G., Li W.L. The accumulation and metabolism of a fluorescent ceramide derivative in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1991;49:143–156. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90137-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huitema K., Van Den Dikkenberg J., Brouwers J.F., Holthuis J.C. Identification of a family of animal sphingomyelin synthases. EMBO Journal. 2004;23:33–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welti R., Mui E., Sparks A., Wernimont S., Isaac G., Kirisits M. Lipidomic analysis of Toxoplasma gondii reveals unusual polar lipids. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13882–13890. doi: 10.1021/bi7011993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonda S., Sala G., Ghidoni R., Hemphill A., Pieters J. Inhibitory effect of aureobasidin A on Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2005;49:1794–1801. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1794-1801.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgopapadakou N.H. Antifungals targeted to sphingolipid synthesis: focus on inositol phosphorylceramide synthase. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2000;9:1787–1796. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.8.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanada K. Sphingolipids in infectious diseases. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;58:131–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mina J.G., Mosely J.A., Ali H.Z., Shams-Eldin H., Schwarz R.T., Steel P.G. A plate-based assay system for analyses and screening of the Leishmania major inositol phosphorylceramide synthase. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2010;42:1553–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mina J.G., Pan S.Y., Wansadhipathi N.K., Bruce C.R., Shams-Eldin H., Schwarz R.T. The Trypanosoma brucei sphingolipid synthase, an essential enzyme and drug target. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2009;168:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heung L.J., Luberto C., Del Poeta M. Role of sphingolipids in microbial pathogenesis. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74:28–39. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.28-39.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stedman T.T., Joiner K.A. En roue to the vacuole:tacing the secretary pathway of Toxoplasma gondii. In: Gordon S., editor. Advances in cell and molecular biology of membranes and organelles. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1999. pp. 233–261. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinai A.P., Webster P., Joiner K.A. Association of host cell endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria with the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole membrane: a high affinity interaction. Journal of Cell Science. 1997;110:2117–2128. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.17.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford M.J., Thomsen-Zieger N., Ray M., Schachtner J., Roos D.S., Seeber F. Toxoplasma gondii scavenges host-derived lipoic acid despite its de novo synthesis in the apicoplast. EMBO Journal. 2006;25:3214–3222. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caffaro C.E., Boothroyd J.C. Evidence for host cells as the major contributor of lipids in the intravacuolar network of Toxoplasma-infected cells. Eukaryotic Cell. 2011;10:1095–1099. doi: 10.1128/EC.00002-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coppens I., Sinai A.P., Joiner K.A. Toxoplasma gondii exploits host low-density lipoprotein receptor-mediated endocytosis for cholesterol acquisition. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;149:167–180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charron A.J., Sibley L.D. Host cells: mobilizable lipid resources for the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Cell Science. 2002;115:3049–3059. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.15.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeanmougin F., Thompson J.D., Gouy M., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1998;23:403–405. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stamatakis A., Hoover J., Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for RAxML web-servers. Systematic Biology. 2008;75:758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denny P.W., Shams-Eldin H., Price H.P., Smith D.F., Schwarz R.T. The protozoan inositol phosphorylceramide synthase: a novel drug target which defines a new class of sphingolipid synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:28200–28209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600796200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merrill A.H., Jr., Sullards M.C., Allegood J.C., Kelly S., Wang E. Sphingolipidomics: high-throughput, structure-specific, and quantitative analysis of sphingolipids by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Methods. 2005;36:207–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanada K., Nishijima M., Akamatsu Y. A temperature-sensitive mammalian cell mutant with thermolabile serine palmitoyltransferase for the sphingolipid biosynthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:22137–22142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanada K., Nishijima M., Kiso M., Hasegawa A., Fujita S., Ogawa T. Sphingolipids are essential for the growth of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Restoration of the growth of a mutant defective in sphingoid base biosynthesis by exogenous sphingolipids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:23527–23533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mina J.G., Okada Y., Wansadhipathi-Kannangara N.K., Pratt S., Shams-Eldin H., Schwarz R.T. Functional analyses of differentially expressed isoforms of the Arabidopsis inositol phosphorylceramide synthase. Plant Molecular Biology. 2010;73:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9626-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagiec M.M., Nagiec E.E., Baltisberger J.A., Wells G.B., Lester R.L., Dickson R.C. Sphingolipid synthesis as a target for antifungal drugs. Complementation of the inositol phosphorylceramide synthase defect in a mutant strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by the AUR1 gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:9809–9817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munoz-Olaya J.M., Matabosch X., Bedia C., Egido-Gabas M., Casas J., Llebaria A. Synthesis and biological activity of a novel inhibitor of dihydroceramide desaturase. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:946–953. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Figueiredo J.M., Dias W.B., Mendonca-Previato L., Previato J.O., Heise N. Characterization of the inositol phosphorylceramide synthase activity from Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochemical Journal. 2005;387:519–529. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanada K., Hara T., Nishijima M., Kuge O., Dickson R.C., Nagiec M.M. A mammalian homolog of the yeast LCB1 encodes a component of serine palmitoyltransferase, the enzyme catalyzing the first step in sphingolipid synthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:32108–32114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Ooij C., Kalman L., van I., Nishijima M., Hanada K., Mostov K. Host cell-derived sphingolipids are required for the intracellular growth of Chlamydia trachomatis. Cellular Microbiology. 2000;2:627–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derre I., Swiss R., Agaisse H. The lipid transfer protein CERT interacts with the Chlamydia inclusion protein IncD and participates to ER-Chlamydia inclusion membrane contact sites. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7:e1002092. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elwell C.A., Jiang S., Kim J.H., Lee A., Wittmann T., Hanada K. Chlamydia trachomatis co-opts GBF1 and CERT to acquire host sphingomyelin for distinct roles during intracellular development. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7:e1002198. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanada K., Kumagai K., Tomishige N., Yamaji T. CERT-mediated trafficking of ceramide. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1791:684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heinzen R.A., Scidmore M.A., Rockey D.D., Hackstadt T. Differential interaction with endocytic and exocytic pathways distinguish parasitophorous vacuoles of Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia trachomatis. Infection and Immunity. 1996;64:796–809. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.796-809.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mack D.G., McLeod R. New micromethod to study the effect of antimicrobial agents on Toxoplasma gondii: comparison of sulfadoxine and sulfadiazine individually and in combination with pyrimethamine and study of clindamycin, metronidazole, and cyclosporin A. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1984;26:26–30. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyake Y., Kozutsumi Y., Nakamura S., Fujita T., Kawasaki T. Serine palmitoyltransferase is the primary target of a sphingosine-like immunosuppressant, ISP-1/myriocin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;211:396–403. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romano J.D., Bano N., Coppens I. New host nuclear functions are not required for the modifications of the parasitophorous vacuole of Toxoplasma. Cellular Microbiology. 2008;10:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali H.Z., Harding C.R., Denny P.W. Endocytosis and sphingolipid scavenging in Leishmania mexicana amastigotes. Biochemistry Research International. 2012;2012:691363. doi: 10.1155/2012/691363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joiner K.A., Roos D.S. Secretory traffic in the eukaryotic parasite Toxoplasma gondii: less is more. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;157:557–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]