Abstract

In order to colonize the host and cause disease, Candida albicans must avoid being killed by host defense peptides. Previously, we determined that the regulatory protein Ssd1 governs antimicrobial peptide resistance in C. albicans. Here, we sought to identify additional genes whose products govern susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides. We discovered that a bcr1Δ/Δ mutant, like the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant, had increased susceptibility to the antimicrobial peptides, protamine, RP-1, and human β defensin-2. Homozygous deletion of BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant did not result in a further increase in antimicrobial peptide susceptibility. Exposure of the bcr1Δ/Δ and ssd1Δ/Δ mutants to RP-1 induced greater loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and increased plasma membrane permeability than with the control strains. Therefore, Bcr1 and Ssd1 govern antimicrobial peptide susceptibility and likely function in the same pathway. Furthermore, BCR1 mRNA expression was downregulated in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant, and the forced expression of BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant partially restored antimicrobial peptide resistance. These results suggest that Bcr1 functions downstream of Ssd1. Interestingly, overexpression of 11 known Bcr1 target genes in the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant failed to restore antimicrobial peptide resistance, suggesting that other Bcr1 target genes are likely responsible for antimicrobial peptide resistance. Collectively, these results demonstrate that Bcr1 functions downstream of Ssd1 to govern antimicrobial peptide resistance by maintaining mitochondrial energetics and reducing membrane permeabilization.

INTRODUCTION

The fungus Candida albicans colonizes the skin and mucosal surfaces of healthy individuals, and colonization is necessary for the organism to cause both superficial and invasive disease. In order to successfully colonize the host and cause disease, C. albicans must resist killing by antimicrobial peptides produced by epithelial cells, leukocytes and platelets. In humans, these antimicrobial peptides include defensins, histatins, cathelicidins, kinocidins, and lactoferrin and transferrin family peptides (1).

Several mechanisms that enable C. albicans to resist the injurious effects of antimicrobial peptides have been identified. These mechanisms include inactivation of antimicrobial peptides via either cleavage by secreted aspartyl proteases (2) or binding by secreted fragments of Msb2 (3). In addition, stress response pathways within the fungus are important for resistance to antimicrobial peptides. For example, an intact Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is required for resistance to multiple antimicrobial peptides (4, 5). Previously, we determined that the regulatory factor Ssd1 plays a key role in antimicrobial peptide resistance in C. albicans (6). A strain in which SSD1 was deleted was hypersusceptible to certain antimicrobial peptides, whereas strains that overexpressed SSD1 were resistant to these peptides. In addition, in a murine model of disseminated candidiasis, an ssd1Δ/Δ null mutant had attenuated virulence, suggesting that Ssd1-mediated antimicrobial peptide resistance may contribute to virulence of C. albicans. However, the mechanism(s) through which SSD1 contributes to antimicrobial peptide resistance in C. albicans was unknown.

The goal of the current study was to identify additional genes whose products mediate peptide resistance in C. albicans. Using a candidate gene approach, we discovered that the BCR1 gene product, a transcription factor, functions downstream of SSD1 to mediate resistance to some antimicrobial peptides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The C. albicans mutant strains used in this study are summarized in Table 1. The 93 clinical strains of C. albicans that were screened were blood isolates obtained from a multicenter surveillance study of candidemia in South Korea (7) All strains were maintained on YPD agar (1% yeast extract [Difco], 2% peptone [Difco], and 2% glucose plus 2% Bacto agar). C. albicans transformants were selected on synthetic complete medium (2% dextrose and 0.67% yeast nitrogen base [YNB] with ammonium sulfate, and auxotrophic supplements). For use in the experiments, the strains were grown in YPD broth in a shaking incubator at 30°C overnight. The resulting yeasts were harvested by centrifugation and enumerated with a hemacytometer as previously described (8).

Table 1.

Strains of C. albicans used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CA024 | Wild type (bloodstream isolate) | |

| CA080 | Wild type (bloodstream isolate) | |

| DAY185 | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG::ARG4-URA3/arg4::hisG | 9 |

| CW195 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 | This study |

| CW193 | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1-BCR1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 | This study |

| rta2 Δ/Δ | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434::URA3 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG rta2::HIS1/rta2::ARG4 | This study |

| APRΔ-1 (ssd1Δ/Δ-I) | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434::URA3 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG ssd1::HIS1/ssd1::ARG4 | 6 |

| APRΔ-1comp (ssd1Δ/Δ-I::SSD1) | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434::URA3 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG ssd1::HIS1/ssd1::ARG4::SSD1 | 6 |

| ssd1Δ/Δ-bcr1Δ/Δ-I and ssd1Δ/Δ-bcr1Δ/Δ-II | ssd1Δ::HIS1/ssd1Δ::ARG4 bcr1Δ::URA3/bcr1Δ::NAT1 ura3Δ::λimm434/ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG | This study |

| ssd1Δ/Δ+BCR1-OE-I and ssd1Δ/Δ+BCR1-OE-II | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434::URA3 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG ssd1::HIS1/ssd1::ARG4 BCR1::pAgTEF1-NAT1-AgTEF1UTR-TDH3-BCR1/BCR1 | This study |

| bcr1Δ/Δ+SSD1-OE-I and bcr1Δ/Δ+SSD1-OE-II | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 SSD1::pAgTEF1-NAT1-AgTEF1UTR-TDH3-SSD1/SSD1 | This study |

| CJN1144 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 TEF1-ALS1::NAT1/ALS1 | 19 |

| CJN1153 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 TEF1-ALS3::NAT1/ALS3 | 19 |

| CJN1222 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 TEF1-HWP1::NAT1/HWP1 | 19 |

| CJN1259 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 TEF1-HYR1::NAT1/HYR1 | 19 |

| CJN1276 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 TEF1-RBT5::NAT1/RBT5 | 19 |

| CJN1281 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 TEF1-CHT2::NAT1/CHT2 | 19 |

| CJN1288 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 TEF1-ECE1::NAT1/ECE1 | 19 |

| JF11 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 PGA10::pAgTEF1-NAT1-AgTEF1UTR-TDH3-PGA10/PGA10 | This study |

| JF25 | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 CSA1::pAgTEF1-NAT1-AgTEF1UTR-TDH3-CSA1/CSA1 | This study |

| bcr1Δ/Δ+MAL31-OE | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 MAL31::pAgTEF1-NAT1-AgTEF1UTR-TDH3-MAL31/MAL31 | This study |

| bcr1Δ/Δ+RTA1-OE | ura3::λimm434/ura3:λimm434 his1::hisG::pHIS1/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 RTA1::pAgTEF1-NAT1-AgTEF1UTR-TDH3-RTA1/RTA1 | This study |

Strain construction.

All C. albicans mutant strains constructed for this study were derived from strain BWP17 (9). Deletion of the entire protein-coding regions of both alleles of RTA2 was accomplished by successive transformation with ARG4 and HIS1 deletion cassettes that were generated by PCR using the primers RTA2-5DR and RTA2-3DR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The resulting strain was subsequently transformed with a URA3-IRO1 fragment, which was released from pBSK-URA3 by NotI/PstI digestion, to reintegrate URA3 at its native locus (8). Proper integration of the URA3-IRO1 fragment was confirmed by PCR using the primers URA3-F and URA3-R (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

To delete the entire protein-coding region of BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant, deletion cassettes containing BCR1 flanking regions and the URA3 or NAT1 selection marker were amplified by PCR with primers BCR1-5DR and BCR1-3DR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), using pGEM-URA3 (9) and pJK795 (10) as templates, respectively. These PCR products were then used to successively transform a Ura− ssa1Δ/Δ strain.

To construct gene overexpression strains, a DNA fragment containing the NAT1 nourseothricin resistance gene and the TDH3 promoter was integrated upstream and adjacent to the protein-coding region of the gene to be overexpressed (11). The TDH3-BCR1 overexpression strains were constructed by transforming C. albicans with a DNA fragment generated by PCR using plasmid pCJN542 (11) as the template and the primers BCR1OE-5′ and BCR1OE-3′ (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Following a similar approach, primers SSD1OE-5′ and SSD1OE-3′ (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used for overexpression of SSD1, primers MAL31OE-5′ and MAL31OE-3′ were used for overexpression of MAL31, and primers RTA1OE-5′ and RTA1OE-3′ were used for overexpression of RTA1.

Radial diffusion assays.

The susceptibilities of the different C. albicans strains to the various antimicrobial peptides (Table 2) were determined using a radial diffusion assay (12). Organisms were mixed with 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid (PIPES) (10 mM, pH 7.5)-buffered agarose at a final concentration of 106 CFU/ml and then added to petri dishes. Next, cylindrical wells were cut into the agar, and 10-μg amounts of the antimicrobial peptides human neutrophil defensin 1 (HNP-1), human β-defensin 2 (hBD-2), LL-37, and RP-1 were added to the wells. After 3 h of incubation at 30°C, the plate was overlaid with YNB agar and incubated at 30°C for 24 h, and then the zone of inhibition were measured. Each experiment was performed at least twice.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial peptides used in this study

| Peptide | Class | Charge | Amino acid sequence | Secondary structure | Tissue source | Proposed mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protamine | Polyamine | +21 | PRRRRSSSRPIRRRRPRRASRRRRRRGGRRRR | Linear/extended | Reproductive tissues | Unknown for fungi | |

| Rational peptide 1 (RP-1) | Synthetic | +8 | ALYKKFKKKLLKSLKRLG | α-Helix | Modeled upon PF-4 α-helices | Perturbation of cell membrane and energetics | Current study |

| Human β-defensin 2 (hBD-2) | β-Defensin | +6 | GIGDPVTCLKSGAICHPVFCPRRYKQIGTCGLPGTKCCKKP | β-Hairpin/helix | Epidermis, mucosa | Perturbation of cell membrane, cell wall, and energetics | 14 |

| Human neutrophil protein 1 (HNP-1) | α-Defensin | +4 | ACYCRIPACIAGERRYGTCIYQGRLWAFCC | β-Hairpin | Neutrophil | Perturbation of cell membrane, ATP efflux and depletion | 31, 32 |

| LL-37 | Cathelicidin | +6 | LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES | Extended/helix | Epidermis, mucosa, neutrophil | Unknown for fungi |

Susceptibility to protamine sulfate and nonpeptide stressors.

The susceptibilities of the various C. albicans strains to protamine and nonpeptide stressors were tested using spot dilution assays. Serial 10-fold dilutions of C. albicans ranging from 105 to 101 CFU were plated in 5-μl volumes on YPD agar containing protamine sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich), SDS, or Congo red and incubated at 30°C. The growth was recorded every 24 h.

The susceptibilities of selected clinical isolates of C. albicans to amphotericin B, fluconazole, voriconazole, caspofungin, and micafungin were determined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M27-A3 method (13).

Real-time PCR.

C. albicans expression of BCR1, RTA2, and SSD1 was determined by real-time PCR. Total RNA was extracted from logarithmic-phase C. albicans cells using the hot-phenol method. In some experiments, the C. albicans strains (107 CFU/ml) were grown in the presence and absence of sublethal concentrations of RP-1 in PIPES (10 mM, pH 7.5) at serial time points prior to RNA extraction. Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out using the SYBR green PCR kit (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI 7000 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's protocol. The primers used in these experiments are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The results were analyzed by the ΔΔCT method, using the transcript level of the C. albicans ACT1 gene as the endogenous control. The mRNA levels for each gene were determined in at least three biological replicates, and the results were combined.

Flow cytometry.

Multicolor flow cytometry was used to assess the effects of the antimicrobial peptides on C. albicans. The fluorophores used were as follows: membrane permeabilization, propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich); transmembrane potential, 3,3-dipentyloxacarbocyanine (DiOC5) (Invitrogen); and phosphatidylserine accessibility, annexin V (allophycocyanin conjugate; Invitrogen) (14). In these experiments, 106 C. albicans cells were incubated with RP-1 (5 μg/ml) in 100 μl PIPES (pH 7.5) for 1 h with shaking at 30°C. The cells were stained for 10 min at room temperature by adding 900 μl stain buffer (PI, 5.0 μg/ml; DiOC5, 0.5 μM; and annexin V, 2.5 μM in 50 mM K+MEM). Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson). The fluorescence of at least 5 × 103 cells was analyzed.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in C. albicans gene expression and susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides were compared by analysis of variance. P values of ≤0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial peptide resistance in clinical C. albicans bloodstream isolates is distinct from antifungal resistance.

To identify naturally occurring C. albicans strains with altered susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides, a panel of 93 bloodstream isolates was screened for susceptibility to protamine, a helical cationic polypeptide that is frequently used to screen for antimicrobial peptide susceptibility (15, 16). Strains with markedly increased or decreased susceptibility to protamine were subsequently tested for susceptibility to other antimicrobial peptides, including RP-1, hBD-2, HNP-1, and LL-37. From this collection of strains, we selected strain CA024 (Amps), which was more susceptible than the DAY185 reference strain to hBD-2, LL-37, and RP-1 (Fig. 1A). We also selected strain CA080 (Ampr), was which less susceptible than strain DAY185 to all peptides tested. Of note, all of these strains had similar susceptibility to amphotericin B, fluconazole, voriconazole, caspofungin, and micafungin (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), suggesting that susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides is unrelated to susceptibility to conventional antifungal agents.

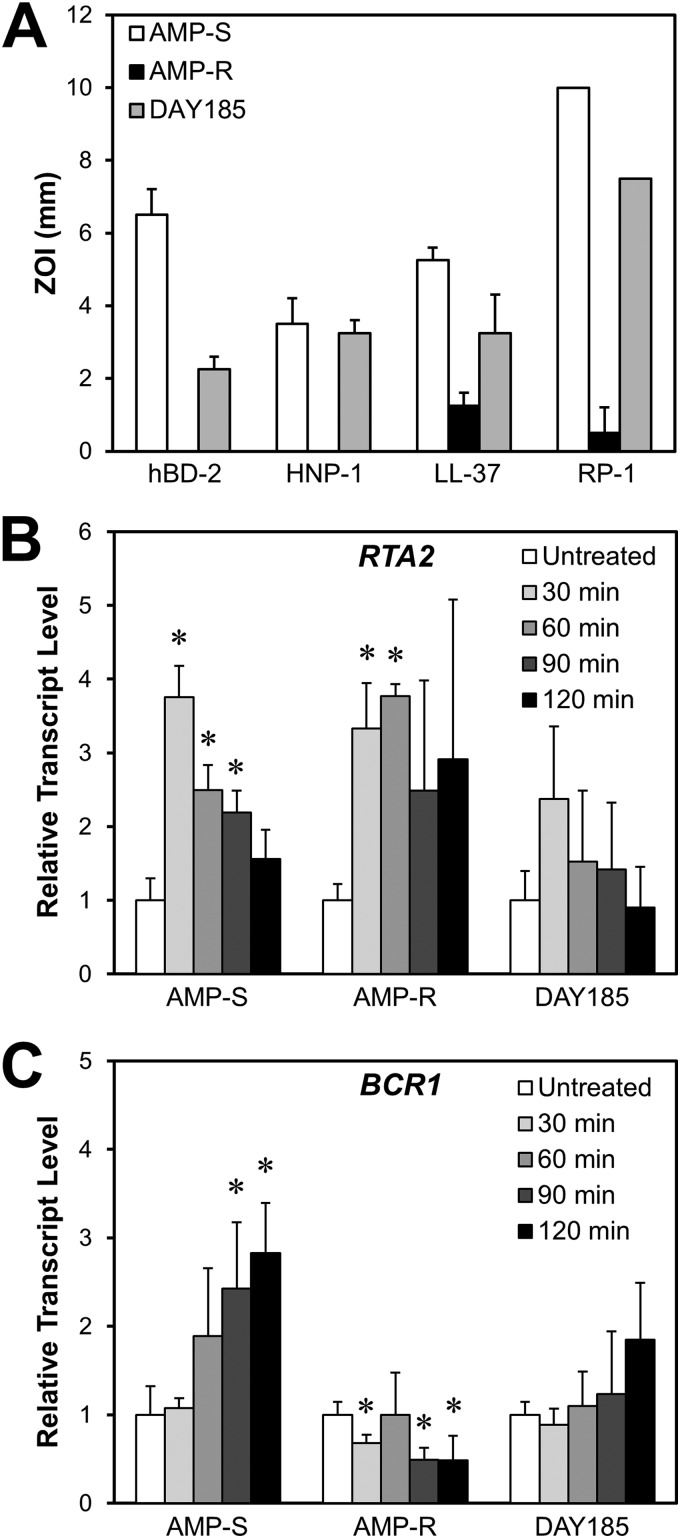

Fig 1.

Comparative antimicrobial peptide susceptibilities and time courses of RTA2 and BCR1 mRNA levels in two C. albicans bloodstream isolates (CA024 [Amps] and CA080 [Ampr]) with differing levels of antimicrobial peptide susceptibility and in the DAY185 reference strain. (A) Susceptibilities of the three C. albicans strains to the indicated antimicrobial peptides were determined by a radial diffusion assay at pH 7.5. Antimicrobial susceptibility was measured as the zone of inhibition (ZOI) after incubation at 30°C for 24 h. Results are means ± standard deviations (SD) from three independent experiments. (B and C) RTA2 (B) and BCR1 (C) transcript levels in the Amps, Ampr, and DAY185 strains after incubation for the indicated time in the presence of a sublethal concentration of RP-1 (2.5 μg/ml for Amps, 100 μg/ml for Ampr, and 5 μg/ml for DAY185). Transcript levels were measured by real-time PCR using ACT1 as the endogenous control gene and normalized to organisms incubated for 60 min in medium without RP-1 (untreated). Results are means ± SD for three biological replicates, each measured in duplicate. *, P < 0.05 compared to cells grown in the absence of RP-1. HNP-1, human neutrophil peptide 1; hBD-2, human β-defensin 2.

Expression profiling of candidate genes indicates that RTA2 and BCR1 are differentially expressed in the Amps and Ampr strains.

To assess the genes whose products mediate antimicrobial peptide resistance in C. albicans, the Amps and Ampr strains were exposed for various times to a sublethal concentration of RP-1 at which 90% of the organisms survived after a 1-h exposure (2.5 μg/ml for the Amps strain, 100 μg/ml for the Ampr strain, and 5 μg/ml for DAY185). Next, we used real-time PCR to compare the transcript levels of 9 candidate resistance genes in these strains. The products of the candidate genes were representative of targets or signaling pathway components known or hypothesized to contribute to microbial resistance to host defense peptides. These candidate genes included ones involved in cell wall integrity (GSL1), cell membrane integrity (RTA2), mitochondrial integrity (MDM10), transcriptional regulation (ADA2, ACE2, BCR1), stress response (HOG1, PBS2), and protein trafficking (VPS51).

We found that among these genes, only RTA2 and BCR1 were differentially expressed between the Amps and Ampr strains in response to the antimicrobial peptide RP-1. RTA2 mRNA levels increased significantly in both isolates after exposure to RP-1 for 30 min (Fig. 1B). However, upon further exposure to RP-1, RTA2 transcript levels progressively decreased in the Amps isolate but not in the Ampr isolate. In strain DAY185, there was a trend toward increased RTA2 transcript levels after 30 min of RP-1 exposure, but this difference did not achieve statistical significance (P = 0.09). The pattern of BCR1 mRNA expression also varied between the Amps and Ampr strains. Upon exposure to RP-1, BCR1 transcript levels progressively increased in the Amps strains but remained at below basal levels in the Ampr strain (Fig. 1C). Although BCR1 mRNA levels in strain DAY185 increased slightly after 120 min of exposure to RP-1, this trend was not statistically significant (P = 0.09). These findings suggested that RTA2 and BCR1 may govern or influence resistance to certain peptides such as RP-1.

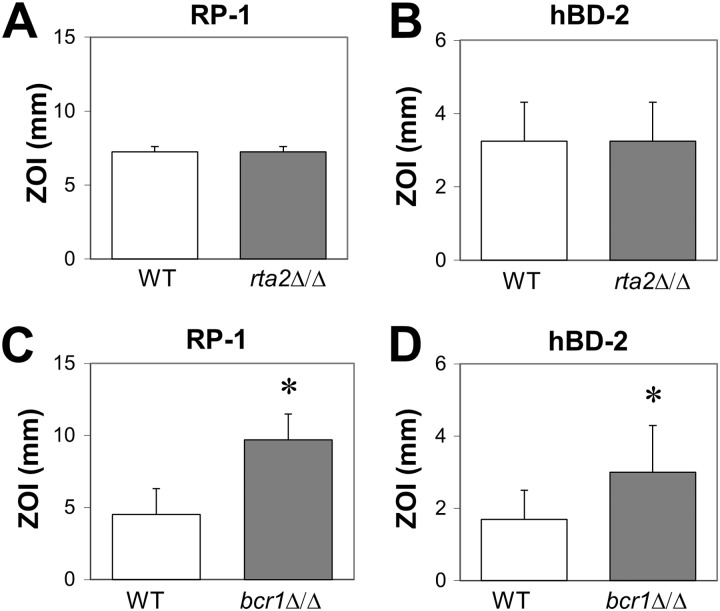

Contributions of RTA2 and BCR1 to intrinsic antimicrobial peptide resistance.

To determine the relationship of RTA2 and BCR1 to antimicrobial peptide resistance, we used a radial diffusion assay to assess the susceptibilities of rta2Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ mutants to antimicrobial peptides with different structure-activity relationships. The rta2Δ/Δ mutant had wild-type susceptibility to RP-1 and hBD-2 (Fig. 2A and B), possibly due to the presence of other members of the RTA gene family (RTA1, RTA3, and RTA4). On the other hand, the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant was more susceptible to both peptides than the wild-type strain (Fig. 2C and D). Thus, BCR1 is necessary for C. albicans to resist RP-1 and hBD-2, whereas RTA2 is not.

Fig 2.

Influence of RTA2 and BCR1 on C. albicans antimicrobial peptide susceptibility. The susceptibilities of the indicated strains of C. albicans to RP-1 (A and C) and hBD-2 (B and D) were determined by a radial diffusion assay after incubation at 30°C for 24 h. Results are the means ± SD from two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared to the wild-type strain (WT).

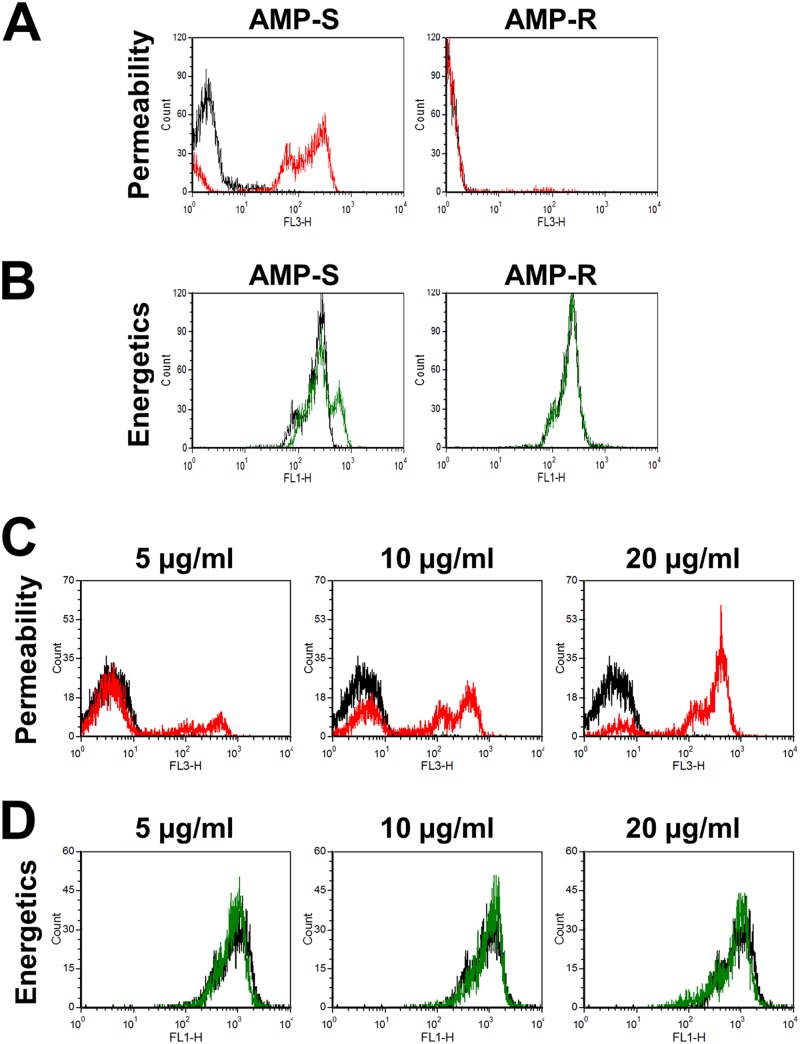

ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ mutants have increased susceptibility to both antimicrobial peptide and membrane stressors.

Previously, we found that SSD1 was required for C. albicans to resist multiple antimicrobial peptides (6). Therefore, we compared the susceptibility to protamine and nonpeptide stressors of an ssd1Δ/Δ mutant with that of the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant. We found that the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant was hypersusceptibile to protamine, the cell membrane stressor SDS, and the cell wall stressor Congo red (Fig. 3). The bcr1Δ/Δ mutant also had increased susceptibility to protamine and SDS, but it had near-wild-type susceptibility to Congo red. As expected, the susceptibility of the ssd1Δ/Δ::SSD1 and bcr1Δ/Δ::BCR1 complemented strains to all stressors was similar to that of the wild-type strain. Collectively, these data indicate that both SSD1 and BCR1 are required for wild-type resistance to both protamine and SDS.

Fig 3.

Susceptibilities of the ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ mutants to protamine and nonpeptide stressors. Images of serial 10-fold dilutions of the indicated strains that were plated onto YPD agar containing 2 mg/ml protamine sulfate, 0.1% SDS, or 300 μg/ml Congo red and incubated at 30°C for 2 days are shown.

BCR1 functions downstream of SSD1.

Next, we investigated the genetic relationship between SSD1 and BCR1 in governing antimicrobial peptide resistance in C. albicans.

To determine if SSD1 and BCR1 function in either a common pathway or parallel pathways, we constructed and analyzed a mutant that lacked both SSD1 and BCR1. The ssd1Δ/Δ bcr1Δ/Δ double mutant had same susceptibility to protamine as the bcr1Δ/Δ single mutant (Fig. 4A), indicating that SSD1 and BCR1 likely function in the same pathway.

Fig 4.

Epistasis analysis of BCR1 and SSD1. (A) Susceptibilities of independent ssd1Δ/Δ bcr1Δ/Δ double deletion mutants to protamine (1.8 mg/ml). (B) Effects of deletion of SSD1 and BCR1 on BCR1 and SSD1 mRNA expression. Total RNA was isolated from the indicated strains grown in YPD at 30°C to early log phase, after which expression of BCR1 and SSD1 was determined by real-time PCR and normalized ACT1. Results are means ± SD for three biological replicates, each measured in duplicate. *, P < 0.05 compared to the wild type (DAY185). (C and D) Effects of overexpression of BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant (C) and overexpression of SSD1 in the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant (D) on susceptibility to protamine (2 mg/ml).

To determine whether BCR1 was upstream or downstream of SSD1, we used real-time PCR to measure BCR1 mRNA expression in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant and SSD1 mRNA expression in the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant. We found that BCR1 transcript levels were reduced in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant compared to the wild-type strain, whereas SSD1 mRNA levels were unchanged in the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant. These findings suggest that BCR1 is downstream of SSD1 (Fig. 4B).

To verify that BCR1 acts downstream of SSD1, we overexpressed BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant and overexpressed SSD1 in the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant by placing a copy of each of these genes under the control of the strong TDH3 promoter. The forced expression of BCR1 in the ssd1ΔΔ mutant partially restored resistance to protamine (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, overexpression of SSD1 in the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant had no effect on resistance to protamine (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these findings suggest that BCR1 governs antimicrobial peptide resistance at least in part by functioning downstream of SSD1.

SSD1 and BCR1 have differing effects on susceptibility to different antimicrobial peptides.

Because different antimicrobial peptides have different structures and modes of action (17), it is likely that resistance to different antimicrobial peptides is governed by distinct signaling pathways. To investigate this possibility, we compared the susceptibilities of the ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ single mutants, the ssd1Δ/Δ PTDH3-BCR1 overexpression strain, and the ssd1Δ/Δ bcr1Δ/Δ double mutant to four different antimicrobial peptides (Table 2; Fig. 5). Both the ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ single mutants had increased susceptibility to the α-helix peptide RP-1 and to the β-hairpin peptide hBD-2. Also, overexpression of BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant partially reversed its hypersusceptibility to these peptides. Interestingly, deletion of BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant resulted in even greater susceptibility to RP-1 but did not further increase susceptibility to hBD-2. These results suggest that both SSD1 and BCR1 mediate C. albicans resistance to RP-1 and hBD-2, and they are consistent with the hypothesis that BCR1 functions downstream of SSD1.

Fig 5.

Effects of SSD1 and BCR1 deletion or overexpression on susceptibility of C. albicans to diverse antimicrobial peptides. The susceptibilities of the indicated strains of C. albicans to HNP-1, hBD-2, LL-37, and RP-1 were measured using a radial diffusion assay. The zones of growth inhibition were imaged after incubation at 30°C for 24 h.

In contrast, SSD1 was necessary for resistance to the β-hairpin peptide HNP-1 and the linear peptide LL-37, whereas BCR1 was not. Only the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant, and not the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant, had increased susceptibility to these peptides (Fig. 5). In addition, neither overexpression of BCR1 nor deletion of BCR1 influenced the susceptibility of the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant to these peptides. Collectively, these results indicate that while SSD1 governs resistance to multiple antimicrobial peptides, BCR1 mediates resistance to only a subset of them.

Both SSD1 and BCR1 are required for resistance to membrane permeabilization and maintenance of mitochondrial membrane potential upon exposure to RP-1.

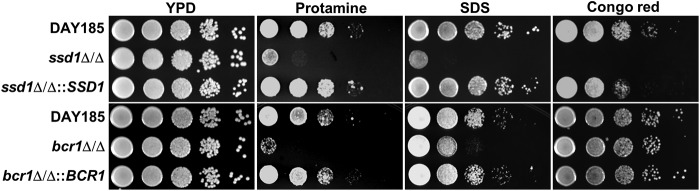

Next, using flow cytometric assays of plasma membrane permeability and mitochondrial membrane potential, we investigated the effects of RP-1 on the different C. albicans strains. Treatment of the Amps strain with RP-1 at 5 μg/ml caused a substantial increase in propidium iodide fluorescence, indicating an increase in membrane permeability (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, the baseline propidium iodide fluorescence of the Ampr strain was lower than that of the Amps strain, and it did not increase after exposure to RP-1. In addition, at the concentration of RP-1 that was used, there was no change DiOC5 fluorescence in either strain, indicating that there was no detectable change in mitochondrial membrane energetics (Fig. 6B). As predicted by the susceptibility data, the response of DAY185 to RP-1 was intermediate to those of the Amps and Ampr strains. Although the baseline propidium iodide membrane permeability of DAY185 was similar to that of the Amps strain, exposure of DAY185 to 5 μg RP-1 per ml resulted in only a modest increase in permeability (Fig. 6C). However, exposure of DAY185 to increasing concentrations of RP-1 resulted in a progressive increase in permeability but had only a modest effect on mitochondrial energetics (Fig. 6D). These data indicate that under the conditions tested, the main effect of RP-1 on susceptible strains of C. albicans is to increase membrane permeability and that any significant effect of RP-1 on mitochondrial energetics must occur after 1 h. The data also suggest that the Ampr strain has an altered plasma membrane, which results in decreased permeability even in the absence of RP-1.

Fig 6.

Effects of RP-1 on C. albicans plasma membrane permeability and mitochondrial membrane potential. The indicated strains of C. albicans were exposed to RP-1 at pH 7.5 for 1 h and then analyzed by flow cytometry. (A and C) Histograms of propidium iodide fluorescence, a measure of membrane permeabilization, of the Amps and Ampr strains exposed to 5 μg/ml RP-1 (A) and of strain DAY185 exposed to 5 to 20 μg/ml RP-1 (C). The fluorescence of untreated control cells is indicated by the black lines, and the fluorescence of cells exposed to RP-1 is indicated by the red lines. (B and D) Histogram of DiOC5 fluorescence, a measure of mitochondrial membrane potential, of the Amps and Ampr strains exposed to 5 μg/ml RP-1 (B) and of strain DAY185 exposed to 5 to 20 μg/ml RP-1 (D). The fluorescence of untreated control cells is indicated by the black lines, and the fluorescence of cells exposed to RP-1 is indicated by the green lines.

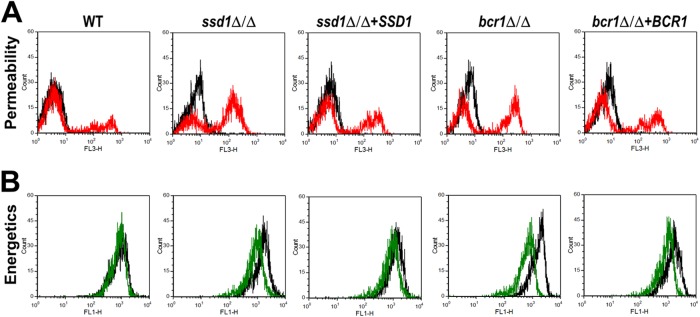

Next, we investigated the mechanisms by which the ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ mutants became hypersusceptible to RP-1. Treatment of both of these mutants with RP-1 caused greater membrane permeabilization than in the DAY185 control strain (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, RP-1 exposure resulted in a reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential in the ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ mutants (Fig. 7B). Importantly, complementation of the ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ mutants largely restored the wild-type phenotype in these assays. Of note, RP-1 did not lead to increased surface exposure of phosphatidylserine in either the ssd1Δ/Δ or bcr1Δ/Δ mutant under the assay conditions used (data not shown), indicating that these mutants did not have greater susceptibility to RP-1-induced programmed cell death within the 1-h time period tested. Therefore, these findings suggest that SSD1 and BCR1 mediate early resistance to RP-1 by maintaining homeostatic membrane integrity and mitochondrial energetics.

Fig 7.

Effects of RP-1 on plasma membrane permeability and mitochondrial membrane potential of the ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ mutants. The indicated strains of C. albicans were exposed to 5 μg/ml RP-1 at pH 7.5 for 1 h and then analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Histogram of propidium iodide fluorescence, a measure of membrane permeabilization. The fluorescence of untreated control cells is indicated by the black lines, and the fluorescence of cells exposed to RP-1 is indicated by the red lines. (B) Histogram of DiOC5 fluorescence, a measure of mitochondrial membrane potential. The fluorescence of untreated control cells is indicated by the black lines, and the fluorescence of cells exposed to RP-1 is indicated by the green lines.

The antimicrobial peptide susceptibility of the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant cannot be rescued by previously known BCR1 target genes.

Prior studies have shown that Bcr1 governs the expression of genes that specify cell surface proteins involved in adherence and biofilm formation, both in vitro and in vivo (18–20). We used an overexpression-rescue approach in an attempt to identify Bcr1 target genes that govern antimicrobial peptide resistance. The susceptibility to protamine was determined for bcr1Δ/Δ strains that overexpressed ALS1, ALS3, CHT2, CSA1, ECE1, HYR1, HWP1, PGA10, RBT5, MAL31, and RTA1. However, none of these strains had restoration of protamine resistance, indicating that other Bcr1 target genes mediate antimicrobial peptide resistance.

DISCUSSION

The current data support the model that Bcr1 mediates resistance to some antimicrobial peptides by functioning downstream of Ssd1. In support of this model, we found that homozygous deletion of either SSD1 or BCR1 rendered C. albicans hypersusceptible to similar stressors, including protamine, RP-1, hBD-2, and SDS. In addition, deletion of either gene resulted in a similar response to RP-1, namely, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and increased membrane permeabilization. Finally, deletion of BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant did not result in increased susceptibility to protamine and hBD-2. Thus, Bcr1 and Ssd1 appear to function in the same pathway. However, Ssd1 appears to govern resistance to a broader spectrum of antimicrobial peptides, and Bcr1 contributes to resistance to a subset of these peptides (Fig. 8).

Fig 8.

Proposed model of the interactions of Ssd1 and Bcr1 in the regulation of C. albicans susceptibility to different antimicrobial peptides.

Ssd1 is an RNA-binding protein and a component of the regulation of Ace2 and morphogenesis (RAM) pathway (21). In C. albicans, this pathway governs multiple processes, including filamentation and cell wall integrity (22, 23). Consistent with our results, others have found that deletion of SSD1 in C. albicans results in increased susceptibility to Congo red (23). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bck1 phosphorylates Ssd1, thereby governing its activity (24). Ssd1 is almost certainly a substrate of Bck1 in C. albicans as well (22). Although the transcription factor Bcr1 was initially found to regulate adherence and biofilm formation, a recent study found that Bcr1 and Ace2 share multiple common target genes, suggesting that Bcr1 may function in the RAM pathway (25). Most importantly, Bck1 was discovered to phosphorylate Bcr1 and regulate its transcriptional activity (26). Thus, Bcr1 and Ssd1 are targets of the same kinase, and this commonality is consistent with the model that Bcr1 and Ssd1 act in the same response pathway to govern susceptibility to certain antimicrobial peptides and SDS.

We also found that BCR1 mRNA expression was reduced in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant and that overexpression of BCR1 in the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant partially restored resistance to protamine, RP-1, and hBD-2. Conversely, SSD1 transcript levels were not reduced in the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant, and overexpression of SSD1 in this strain failed to restore antimicrobial peptide resistance. Collectively, these results indicate that Bcr1 functions downstream of Ssd1. Whether Ssd1 governs BCR1 mRNA expression directly or indirectly is not yet known. However, in S. cerevisiae, Ssd1 binds to specific mRNAs, governing their localization within the cell and inhibiting their translation (24). If Ssd1 functions similarly in C. albicans, we would predict that it influences BCR1 mRNA levels by an indirect mechanism.

Although Bcr1 and Ssd1 function in the same pathway, our data indicate that Ssd1 governs resistance to a wider range of stressors than Bcr1. For example, the ssd1Δ/Δ mutant was highly susceptible to Congo red, HNP-1, and LL-37, whereas the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant was not. These results indicate that Ssd1 governs resistance to these stressors independently of Bcr1 and suggest that there must be incomplete overlap among Bcr1 and Ssd1 target genes.

Interestingly, although Ace2 and Bcr1 are both members of the RAM pathway and both govern biofilm formation, we found that an ace2Δ/Δ mutant had wild-type susceptibility to protamine and RP-1 (S. Jung and S. Filler, unpublished data). Therefore, either Ace2 target genes are not involved in resistance to the study antimicrobial peptides under the conditions tested or the compensatory changes in the cell wall induced by deletion of ACE2 mask any increase in susceptibility to these peptides under these experimental conditions.

Even though the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant had increased susceptibility to several antimicrobial peptides, it seemed paradoxical that BCR1 mRNA levels were upregulated in the Amps clinical isolate. We speculate that this upregulation of BCR1 represents a compensatory response and that the Amps strain is hypersusceptible to antimicrobial peptides by another mechanism.

Although the mechanisms by which antimicrobial peptides kill bacteria have been studied extensively, less is known about how they antagonize fungi. Under the specific time and conditions tested, we found that the major effect of RP-1 on the Amps and DAY185 strains was to cause an increase in membrane permeability. At the concentration tested, RP-1 did not increase membrane permeability in the Ampr strain, which was highly resistant to the growth-inhibitory effects of RP-1. The finding that the capacity of RP-1 to induce membrane permeabilization directly correlated with its capacity to inhibit growth supports the model that induction of membrane permeabilization is a key component of the antifungal activity of this peptide.

RP-1 had different effects on mitochondrial energetics in different strains. Under the conditions tested, RP-1 had minimal effects on the mitochondrial energetics of any of the wild-type strains. However, it markedly reduced the mitochondrial energetics of both the ssd1Δ/Δ and bcr1Δ/Δ mutants. These results suggest that Ssd1 and Bcr1 are required for C. albicans to sustain mitochondrial membrane potential when exposed to RP-1. Furthermore, it is possible that the upregulation of BCR1 that occurred when the Amps strain was exposed to RP-1 prevented this strain from losing mitochondrial membrane potential, even though it was still killed. In prior studies, we have shown that certain antimicrobial peptides can induce programmed cell death-like effects (e.g., phosphatidylserine accessibility) in C. albicans, particularly after 2 hours or more of exposure (14). However, in the current study, which focused on the early (1-h) response profile, no such effects were observed. Future studies will investigate the roles of Bcr1 and Ssd1 in early versus late mechanisms of resistance to antimicrobial peptides.

It is notable that the signaling pathways that govern biofilm formation in the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa also regulate susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides. For example, a P. aeruginosa mutant that lacks the transcriptional regulator PsrA is defective in biofilm formation and has increased susceptibility to the bovine neutrophil antimicrobial peptide indolicidin (27). Moreover, PhoQ, which is a member of a two-component regulatory system, governs both biofilm formation and antimicrobial peptide resistance in P. aeruginosa and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (28–30). Based on the link between biofilm formation and antimicrobial peptide resistance in organisms from two different phyla, it seems probable that both processes depend on factors that influence the cell wall and cell surface.

We attempted to identify Bcr1 target genes that mediate antimicrobial peptide resistance using an overexpression-rescue approach that was focused on genes involved in biofilm formation and cell wall structure. However, none of the overexpressed genes reversed the antimicrobial peptide susceptibility of the bcr1Δ/Δ mutant. Thus, it is likely that other Bcr1 target genes are responsible for resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Alternatively, Bcr1-mediated resistance may require the simultaneous action of multiple downstream genes. Future work to identify the Bcr1 target genes that mediate resistance to antimicrobial peptides holds promise to provide new insights into the mechanisms by which C. albicans resists this key host defense mechanism. In turn, identification of such resistance genes and proteins may reveal novel antifungal targets for improved prevention or therapy of fungal infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2010-013-E00023) and the National Institutes of Health (R01AI054928, R01DE017088, and R01AI39001).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00285-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Yount NY, Yeaman MR. 2012. Emerging themes and therapeutic prospects for anti-infective peptides. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 52: 337– 360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meiller TF, Hube B, Schild L, Shirtliff ME, Scheper MA, Winkler R, Ton A, Jabra-Rizk MA. 2009. A novel immune evasion strategy of Candida albicans: proteolytic cleavage of a salivary antimicrobial peptide. PLoS One 4: e5039 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Szafranski-Schneider E, Swidergall M, Cottier F, Tielker D, Roman E, Pla J, Ernst JF. 2012. Msb2 shedding protects Candida albicans against antimicrobial peptides. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002501 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vylkova S, Jang WS, Li W, Nayyar N, Edgerton M. 2007. Histatin 5 initiates osmotic stress response in Candida albicans via activation of the Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1876– 1888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Argimon S, Fanning S, Blankenship JR, Mitchell AP. 2011. Interaction between the Candida albicans high-osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway and the response to human beta-defensins 2 and 3. Eukaryot. Cell 10: 272– 275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gank KD, Yeaman MR, Kojima S, Yount NY, Park H, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG, Fu Y. 2008. SSD1 is integral to host defense peptide resistance in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 7: 1318– 1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jung SI, Shin JH, Song JH, Peck KR, Lee K, Kim MN, Chang HH, Moon CS. 2010. Multicenter surveillance of species distribution and antifungal susceptibilities of Candida bloodstream isolates in South Korea. Med. Mycol. 48: 669– 674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park H, Myers CL, Sheppard DC, Phan QT, Sanchez AA, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG. 2005. Role of the fungal Ras-protein kinase A pathway in governing epithelial cell interactions during oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell. Microbiol. 7: 499– 510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilson RB, Davis D, Mitchell AP. 1999. Rapid hypothesis testing with Candida albicans through gene disruption with short homology regions. J. Bacteriol. 181: 1868– 1874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shen J, Guo W, Kohler JR. 2005. CaNAT1, a heterologous dominant selectable marker for transformation of Candida albicans and other pathogenic Candida species. Infect. Immun. 73: 1239– 1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nobile CJ, Solis N, Myers CL, Fay AJ, Deneault JS, Nantel A, Mitchell AP, Filler SG. 2008. Candida albicans transcription factor Rim101 mediates pathogenic interactions through cell wall functions. Cell. Microbiol. 10: 2180– 2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yount NY, Yeaman MR. 2004. Multidimensional signatures in antimicrobial peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101: 7363– 7368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts, 3rd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yount NY, Kupferwasser D, Spisni A, Dutz SM, Ramjan ZH, Sharma S, Waring AJ, Yeaman MR. 2009. Selective reciprocity in antimicrobial activity versus cytotoxicity of hBD-2 and crotamine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106: 14972– 14977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yeaman MR, Soldan SS, Ghannoum MA, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG, Bayer AS. 1996. Resistance to platelet microbicidal protein results in increased severity of experimental Candida albicans endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 64: 1379– 1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park H, Liu Y, Solis N, Spotkov J, Hamaker J, Blankenship JR, Yeaman MR, Mitchell AP, Liu H, Filler SG. 2009. Transcriptional responses of Candida albicans to epithelial and endothelial cells. Eukaryot. Cell 8: 1498– 1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yeaman MR, Yount NY. 2003. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol. Rev. 55: 27– 55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fanning S, Xu W, Solis N, Woolford CA, Filler SG, Mitchell AP. 2012. Divergent targets of Candida albicans biofilm regulator Bcr1 in vitro and in vivo. Eukaryot. Cell 11: 896– 904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nobile CJ, Andes DR, Nett JE, Smith FJ, Yue F, Phan QT, Edwards JE, Filler SG, Mitchell AP. 2006. Critical role of Bcr1-dependent adhesins in C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2: e63 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nobile CJ, Mitchell AP. 2005. Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Curr. Biol. 15:1150– 1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saputo S, Chabrier-Rosello Y, Luca FC, Kumar A, Krysan DJ. 2012. The RAM network in pathogenic fungi. Eukaryot. Cell 11: 708– 717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bharucha N, Chabrier-Rosello Y, Xu T, Johnson C, Sobczynski S, Song Q, Dobry CJ, Eckwahl MJ, Anderson CP, Benjamin AJ, Kumar A, Krysan DJ. 2011. A large-scale complex haploinsufficiency-based genetic interaction screen in Candida albicans: analysis of the RAM network during morphogenesis. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002058 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Song Y, Cheon SA, Lee KE, Lee SY, Lee BK, Oh DB, Kang HA, Kim JY. 2008. Role of the RAM network in cell polarity and hyphal morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:5456– 5477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jansen JM, Wanless AG, Seidel CW, Weiss EL. 2009. Cbk1 regulation of the RNA-binding protein Ssd1 integrates cell fate with translational control. Curr. Biol. 19: 2114– 2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Finkel JS, Xu W, Huang D, Hill EM, Desai JV, Woolford CA, Nett JE, Taff H, Norice CT, Andes DR, Lanni F, Mitchell AP. 2012. Portrait of Candida albicans adherence regulators. PLoS Pathog. 8: e1002525 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gutierrez-Escribano P, Zeidler U, Suarez MB, Bachellier-Bassi S, Clemente-Blanco A, Bonhomme J, Vazquez de Aldana CR, d'Enfert C, Correa-Bordes J. 2012. The NDR/LATS kinase Cbk1 controls the activity of the transcriptional regulator Bcr1 during biofilm formation in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002683 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gooderham WJ, Bains M, McPhee JB, Wiegand I, Hancock RE. 2008. Induction by cationic antimicrobial peptides and involvement in intrinsic polymyxin and antimicrobial peptide resistance, biofilm formation, and swarming motility of PsrA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 190:5624– 5634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gooderham WJ, Gellatly SL, Sanschagrin F, McPhee JB, Bains M, Cosseau C, Levesque RC, Hancock RE. 2009. The sensor kinase PhoQ mediates virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 155: 699– 711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prouty AM, Gunn JS. 2003. Comparative analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium biofilm formation on gallstones and on glass. Infect. Immun. 71: 7154– 7158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shprung T, Peleg A, Rosenfeld Y, Trieu-Cuot P, Shai Y. 2012. Effect of PhoP-PhoQ activation by broad repertoire of antimicrobial peptides on bacterial resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 4544– 4551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vylkova S, Li XS, Berner JC, Edgerton M. 2006. Distinct antifungal mechanisms: beta-defensins require Candida albicans Ssa1 protein, while Trk1p mediates activity of cysteine-free cationic peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50: 324– 331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Edgerton M, Koshlukova SE, Araujo MW, Patel RC, Dong J, Bruenn JA. 2000. Salivary histatin 5 and human neutrophil defensin 1 kill Candida albicans via shared pathways. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44: 3310– 3316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.