Abstract

Aggressive cancers in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phase are characterized by loss of cell adhesion, repression of E-cadherin, and increased cell mobility. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) differs in basal level of E-cadherin; predominantly exhibiting silenced expression due to epigenetic-related modifications. Accordingly, effective treatments are needed to modulate these epigenetic events that in turn can positively regulate E-cadherin levels. Herein, we investigated silibinin, a natural flavonolignan with anticancer efficacy against lung cancer, either alone or in combination with epigenetic therapies to modulate E-cadherin expression in a panel of NSCLC cell lines. Silibinin combined with HDAC inhibitor Trichostatin A [TSA; 7-[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]-N-hydroxy-4,6-dimethyl-7-oxohepta-2,4-dienamide] or DNMT inhibitor 5′-Aza-deoxycytidine (Aza) significantly restored E-cadherin levels in NSCLC cells harboring epigenetically silenced E-cadherin expression. These combination treatments also strongly decreased the invasion/migration of these cells, which further emphasized the biologic significance of E-cadherin restoration. Treatment of NSCLC cells, with basal E-cadherin levels, by silibinin further increased the E-cadherin expression and inhibited their migratory and invasive potential. Additional studies showed that silibinin alone as well as in combination with TSA or Aza downmodulate the expression of Zeb1, which is a major transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin. Overall these findings demonstrate the potential of combinatorial treatments of silibinin with HDAC or DNMT inhibitor to modulate EMT events in NSCLC cell lines, leading to a significant inhibition in their migratory and invasive potentials. These results are highly significant, since loss of E-cadherin and metastatic spread of the disease via EMT is associated with poor prognosis and high mortalities in NSCLC.

Introduction

Lung cancer is a deadly malignancy that is the leading cause of cancer-related mortalities globally (Ferlay et al., 2010). Despite the advancements in treatment options, the 5-year survival rate for lung cancer remains ∼15%. This is primarily attributed to the early metastatic spread of the disease within the lung and to distant organs, which involves epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of lung cancer cells including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells (Denlinger et al., 2010). NSCLC cells differ widely in their basal level of E-cadherin, which is an epithelial marker and responsible for the "integrity of the cell" by maintaining cell polarity, cell shape, and cell-cell contact (Lim et al., 2000; Bremnes et al., 2002; Chaffer and Weinberg, 2011). The differential expression of E-cadherin in NSCLC cell lines is due to its epigenetic silencing via deacetylation- and methylation-related events regulated by epigenetic enzymes, e.g., histone deacetylases (HDACs) and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) that deacetylate histones and methylate DNA, respectively (Johnstone, 2002; Jones and Baylin, 2002; Belinsky, 2004; Witta et al., 2006). This condenses the chromatin and thereby mechanistically silences the expression of several tumor suppressor genes including E-cadherin (Johnstone, 2002; Jones and Baylin, 2002; Belinsky, 2004; Witta et al., 2006).

In NSCLC cells, E-cadherin expression is downmodulated primarily through HDACs, which can be augmented by HDAC inhibitors (Marks et al., 2000; Witta et al., 2006; Kakihana et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). HDACs act in concert with other chromatin modifying enzymes, particularly DNMTs that methylate the gene promoter regions; E-cadherin has been reported to undergo methylation in ∼18% of the NSCLC tumor samples, as well as in NSCLC cell lines including H1299 (Zochbauer-Muller et al., 2001; Shames et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2009). Furthermore, loss of E-cadherin is an important parameter associated with resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy. Unlike resistant cells, NSCLC cell lines that are highly sensitive to EGFR TKIs retain moderate to high levels of E-cadherin (Yauch et al., 2005; Soltermann et al., 2008; Kakihana et al., 2009). Moreover, loss of E-cadherin is associated with poor prognosis and is a major contributor to the early mortalities in NSCLC patients (Lim et al., 2000; Thompson et al., 2005; Yauch et al., 2005; Witta et al., 2006; Frederick et al., 2007; Soltermann et al., 2008). In NSCLC cell lines, E-cadherin expression is modulated through two main signaling pathways, namely β-catenin and zinc finger proteins, including transcriptional repressors Snail, Slug, Zeb1, and SIP1 (Zeb2) (Postigo and Dean, 1999; Ohira et al., 2003; Peinado et al., 2004; Witta et al., 2006; Kakihana et al., 2009; Schmalhofer et al., 2009). Cooperative interactions between these transcriptional repressors and CtBP (a corepressor complex) promote the recruitment of epigenetic enzymes such as HDACs to negatively regulate E-cadherin expression (Peinado et al., 2004; Spaderna et al., 2008; Drake et al., 2009; Gemmill et al., 2011; Aghdassi et al., 2012). Among these transcriptional repressors, elevated levels of Zeb1 mRNA have been shown to be correlated with the loss of E-cadherin expression, especially in the EFGR-TKI insensitive NSCLC cell lines (Witta et al., 2006).

Several inhibitors of epigentic enzymes have shown potential in NSCLC control and are in clinical trials; however, their toxicity and cancer cell resistance are the limiting factors (Fantin and Richon, 2007; Issa and Kantarjian, 2009; Schrump, 2009; Robey et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2012). Some of these drugs include HDAC inhibitors [HDACi; e.g., Trichostatin A (TSA)] and DNMT inhibitors [DNMTi; e.g., 5′-Aza-deoxycytidine (Aza)], which are used in combination with each other or other agents to potentiate/synergize their efficacy (Belinsky et al., 2003; Zhong et al., 2007; Bots and Johnstone, 2009; Meeran et al., 2010). Thus, the overall emphasis is to develop effective and safe treatment regimens that could modulate epigenetic events in favor of positively regulating E-cadherin levels in NSCLC cell lines (Neal and Sequist, 2012) and thereby exert their anticancer activity.

In this regard, silibinin, a nontoxic chemopreventive agent, has shown strong anticancer efficacy against NSCLC cells in culture and nude mice (Mateen et al., 2010), together with the potential to alter enzymatic activity and protein levels of HDACs in NSCLC cells (Mateen et al., 2012). Specifically, silibinin was found to inhibit HDAC activity and decrease HDAC 1-3 levels in NSCLC cells, leading to an overall increase in global histone acetylation states of H3 and H4 (Mateen et al., 2012). Accordingly, here we examined the effect of silibinin, either alone or in combination with epigenetic therapies (HDAC or DNMT inhibitor), on regulating the mechanisms that are responsible for silencing E-cadherin in NSCLC cells. Furthermore, we also assessed whether such molecular alterations could be translated to the biologically relevant invasion and migration events of NSCLC cells with epigenetically silenced E-cadherin levels (H1299 and H157 cells) and those with basal E-cadherin levels (H322 and H358 cells).

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Treatments.

NSCLC cell lines were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and were tested and authenticated by polymorphic short tandem repeat profiling. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 U/ml of penicillin G and 100 mg/ml of streptomycin sulfate and maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. For experimental treatments, H1299 cells were plated and next day treated with either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (control), 3.75–12.5 µM silibinin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.33–1 µM TSA (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) or 1–5 µM Aza (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 or 48 hours. Similarly, H322 and H358 cells were plated and following day, treated with either DMSO (control) or 12.5 µM of silibinin for 120 hours. For cotreatments, H1299 cells were exposed to DMSO (control), silibinin (3.75 µM), TSA (0.5 µM), and Aza (5 µM), either alone or in combinations for 24–48 hours. The final concentration of DMSO in medium during different treatments did not exceed 0.1% (v/v). Compared with previous studies in which we assessed the cell growth inhibitory activity of silibinin (up to 75 µM concentration) in lung cancer cells (Mateen et al., 2010, 2012), here we chose relatively lower doses of silibinin (3.75–12.5 µM) so that silibinin alone or in combination with other drugs does not affect growth and death of NSCLC cells and thus could be used for future invasion and migration studies.

Immunoblotting.

Total cell lysates were prepared in nondenaturing lysis buffer and following estimation of protein concentration in lysates using BioRad DC protein assay kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA), 50–100 µg of protein lysate per sample was denatured in 2× sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 6 or 8% Tris-glycine gel. Separated proteins were transferred on to nitrocellulose membrane by Western blotting and membrane blocked for 1 hour in Odyssey blocking buffer and then incubated with specific primary antibodies, followed by either goat anti-rabbit 800 or goat anti-mouse 680 IR secondary antibody (both at 1:5,000 dilution) for 45 minutes. After the final wash, membranes were scanned using the Odyssey Infrared Imager (84 μm resolution, 0 mm offset with medium or high quality; LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). The antibodies used were E-cadherin (24E10) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) and Zeb1 (H-102) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Each membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) to ensure equal protein loading. As applicable, densitometric analysis of immunoblots was done by Scion Image program (NIH, Bethesda, MD), and densitometric values were adjusted to loading controls.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were fixed in 4% buffered formalin followed by incubation with ice cold 100% methanol. Cells were then blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline for 60 minutes and then incubated overnight at 4°C with desired primary antibodies. The following day, cells were incubated for 60 minutes with appropriate Alexa fluor secondary antibody and counterstained with DAPI for 5 minutes. Stained cell images were captured at 400× magnification using a Nikon D-Eclipse C1 confocal microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed using EZ-C1 Free viewer software (Nikon).

Invasion Assay.

Invasive potential of NSCLC was determined using matrigel coated trans-well chambers (8-micrometer pore size) from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). H1299 cells were plated in 100-mm plates and the following day were treated with DMSO (control), silibinin (3.75 µM), TSA (0.5 µM), and Aza (5 µM) alone or in combinations for 36 hours. After drug treatment, cells were harvested by brief trypsinization in all treatment groups, and then equal live cell numbers from these individual cell harvests were seeded in the upper chambers of trans-well in RPMI media containing 0.5% FBS in presence of drugs treatment. Similarly, H322 cells that were either untreated or treated with 12.5 µM silibinin for 96 hour were harvested and live equal cell numbers were seeded in the upper trans-well chambers. The lower chambers consisted of RPMI media containing 10% FBS. After 12–24 hours of incubation under standard culture conditions in the continuous presence of drugs treatment, noninvasive cells present on the upper surface of the membrane were scraped with cotton swabs, and the invasive cells present on the lower side of the membrane were fixed with ice-cold methanol, stained with hematoxylin/eosin, and mounted on glass slides. Images were captured using Canon Power Shot A640 camera (Canon, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) on a Zeiss inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany), and the invasive cells were manually counted at 400×.

Migration Assay.

Migration assay was performed similar to invasion assay described above, but trans-well chambers lacked the matrigel layer. All drug treatments were the same as detailed earlier. At similar time points, as in invasion assay, experiments were first conducted in the presence of drugs and then continued in their absence (drug-wash out studies) to assess the reversibility of drug effects in NSCLC cells.

Statistical Analyses.

Difference between treatment groups was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni t test using Sigma stat 2.03 software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Differential Effects of Silibinin, HDACi, and DNMTi on Re-expression of E-cadherin in NSCLC H1299 Cells.

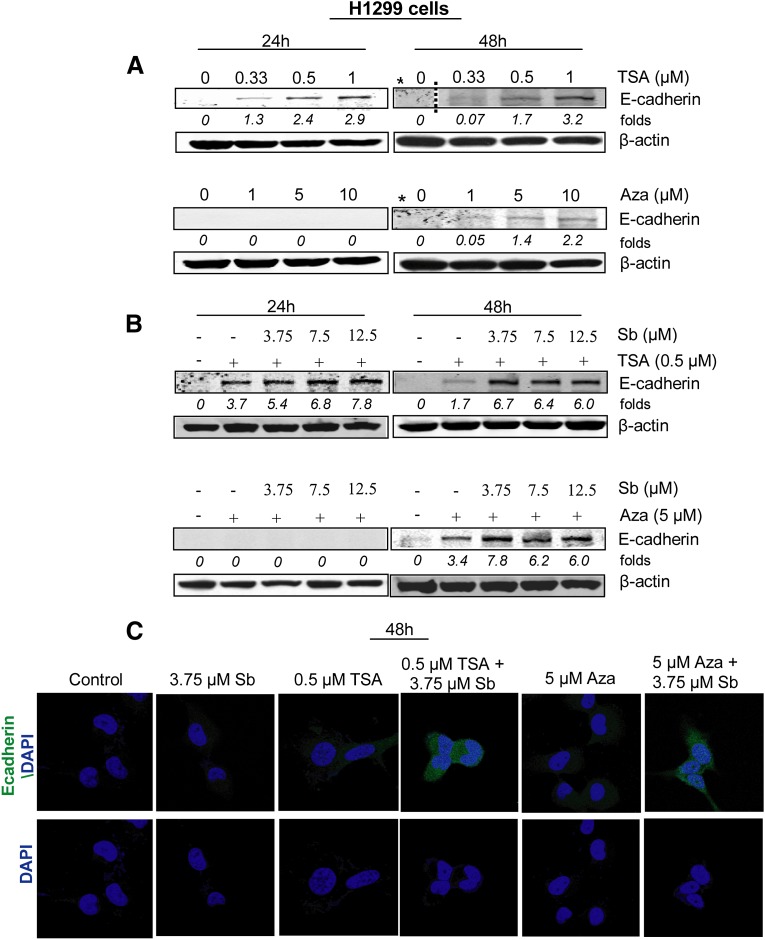

To compare the effect of silibinin, HDACi and DNMTi alone on the induction of E-cadherin levels, we first conducted a dose- and a time-dependent study with these agents alone in NSCLC H1299 cells. The cells were treated with DMSO (control), silibinin (3.75–12.5 µM), TSA (0.33–1 µM), or Aza (1–5 µM) for 24-48 hours, and then lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for E-cadherin expression (Fig. 1A). Silibinin alone could not re-express the epigenetically silenced E-cadherin levels during 24–48 hours of its treatment (data not shown because the immunoblot for E-cadherin was totally blank). The exposure of cells to HDACi (TSA) caused an increase in E-cadherin protein levels in a dose-dependent manner; however, the increase was more evident by 24 hours and tended to decrease by prolonged exposure (48 hours) as has been reported earlier for this HDACi (Kakihana et al., 2009). Conversely, H1299 cells treated with DNMTi (Aza) did not show early restoration of E-cadherin expression, but the drug significantly increased E-cadherin protein levels at later time points (48 hours) (Fig. 1A). These results showed that in H1299 cells, HDAC and DNMT inhibitors do elevate E-cadherin protein expression, as would be expected, by inhibiting chromatin-modifying enzymes that cause E-cadherin silencing.

Fig. 1.

Combination of silibinin with epigenetic therapeutics (HDAC or DNMT inhibitor) increases E-cadherin expression in NSCLC H1299 cells. H1299 cells were treated with either DMSO (control), silibinin (3.75–12.5 µM), TSA (0.33–1 µM), and Aza (1–10 µM) alone or in combination for indicated time points. Cell lysates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. (A-B) E-cadherin protein expression in total cell lysates after different treatments as labeled. (C) Immunofluorescence staining for E-cadherin (green)- and DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) after different treatments in H1299 cells. *Both TSA and Aza were run on the same gel at 48-hour time points, hence share the same control.

Synergistic Effect of Silibinin in Combination with Epigenetic Therapies (HDACi or DNMTi) on the Induction of E-cadherin Expression.

Next, we used one dose of TSA (0.5 µM) and Aza (5 µM) alone or in combination with low doses of silibinin (3.75–12.5 µM) and examined their effect on re-expression of E-cadherin levels in H1299 cells by immunoblotting (Fig. 1B) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 1C). The doses of HDAC and DNMT inhibitors were chosen based on their effect in moderately increasing E-cadherin protein levels. As shown in Fig. 1B, cotreatments of TSA + silibinin for 24 hours caused a marked increase in E-cadherin protein expression compared with single agent alone. Moreover, at 48 hours, when the E-cadherin level started to gradually decline in HDACi alone treatment, silibinin combination resulted in a strong increase in E-cadherin levels. Furthermore, a combination treatment of Aza + silibinin for 48 hours also increased E-cadherin levels, suggesting that silibinin treatments along with epigenetic drugs were effective in inducing E-cadherin levels.

Combinatorial Treatment of Silibinin with HDACi or DNMTi Inhibits the Migration and Invasion of NSCLC H1299 Cells.

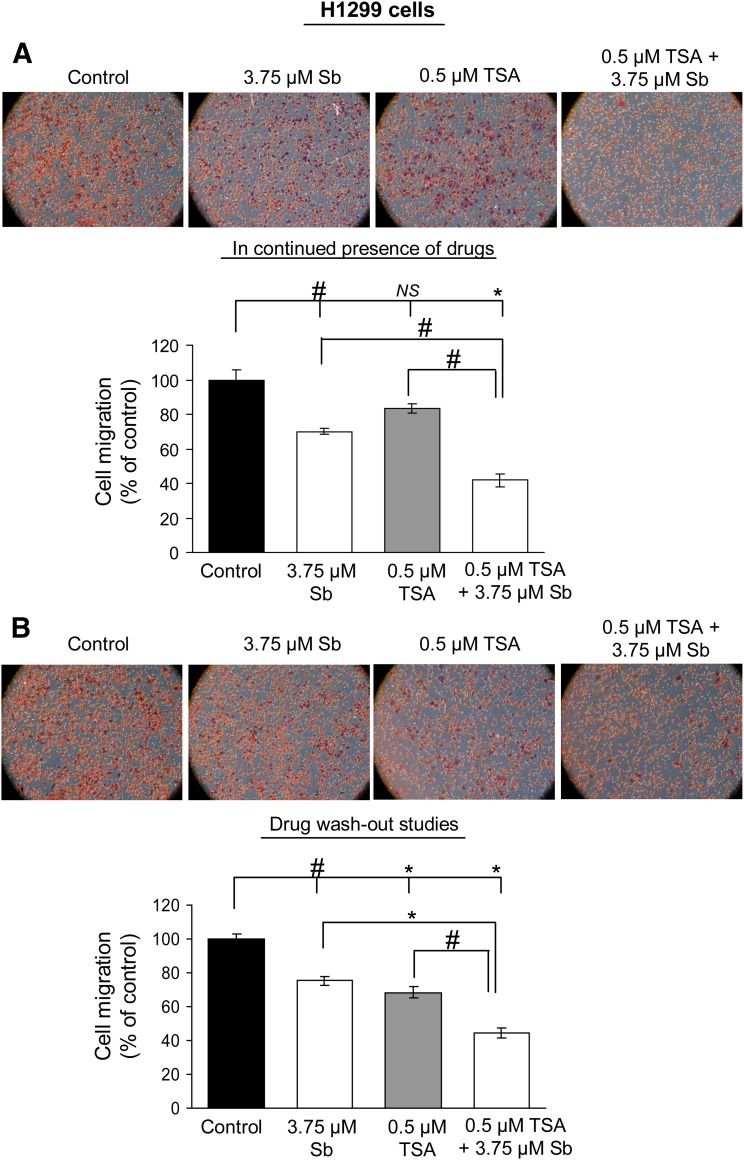

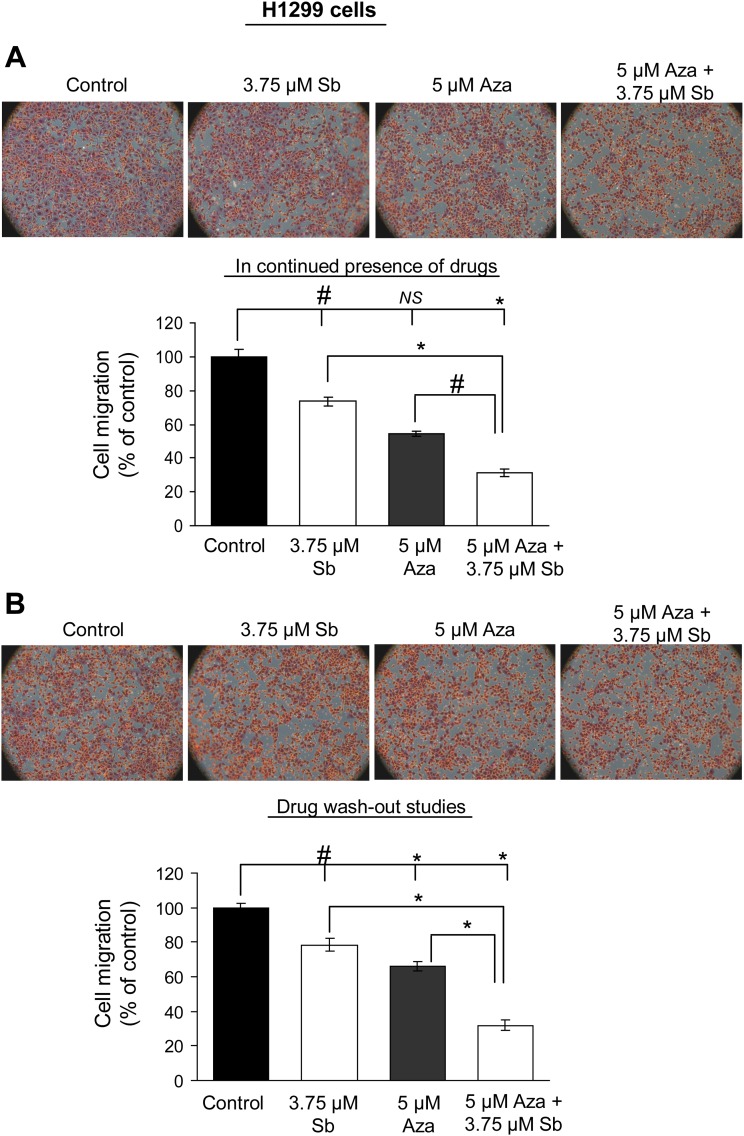

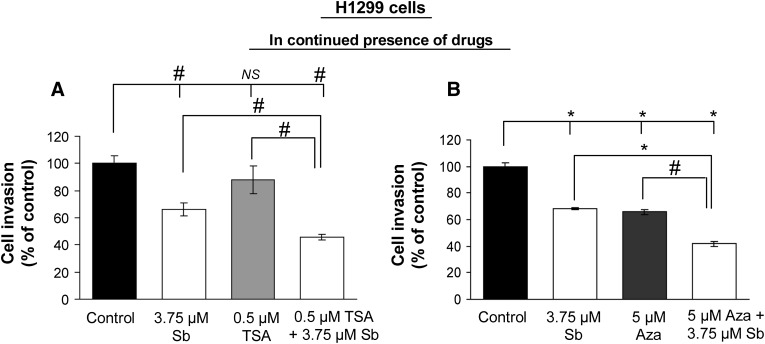

E-cadherin is considered to be a master regulator of EMT, and its disruption stimulates cancer cell invasion and migration, contributing to aggressive cellular phenotype (Thiery, 2002). To understand the biologic significance of E-cadherin re-expression by silibinin in combination with HDACi or DNMTi, we next conducted migration and invasion assays in H1299 cells. Cells were exposed to single or combination treatment of drugs, and after 36 hours, an equal number of live cells in each treatment group was replated in migration chambers in presence of drugs until the completion of 48 hours of treatment time. Our results show that combination treatments reduced cell migration by 58% and 69% (P < 0.001, for both) in TSA + silibinin and Aza + silibinin treatment groups, respectively (Figs. 2A and 3A). Also, whereas TSA alone was ineffective, both silibinin and Aza alone also inhibited cell migration by 26–30% (P < 0.05) and 46% (P < 0.001), respectively. Next, reversibility of these effects was tested by drug wash-out studies (Figs. 2B and 3B), wherein after initial combination treatment of cells with drugs for 36 hours, equal live cell numbers in each treatment group were replated in the trans-well invasion chambers in the absence of drug treatment until the completion of the next 12 hours. As shown in Figs. 2B and 3B, even in the absence of further drug treatment, silibinin in combination with either TSA or Aza was able to significantly inhibit (by 56 and 68%, P < 0.001, respectively) the migration of H1299 cells in an irreversible fashion. Next, under similar treatment conditions, the effect of these drug treatments on the invasive potential of H1299 cells was also evaluated. The combination treatments of TSA + silibinin and Aza + silibinin significantly reduced the invasion of H1299 cells compared with single agents alone (Fig. 4, A and B).

Fig. 2.

Silibinin in combination with TSA inhibits the migratory potential of H1299 cells. H1299 cells were treated with DMSO (control) or silibinin (3.75 µM) alone or in combination with TSA (0.5 µM) for 48 hours. Migratory potential was examined using migration chambers either in continuous presence (A) or absence (B) (wash-out studies) of drug treatment of H1299 cells. Cell migration data shown are mean ± S.E.M. of three samples. #P < 0.05; *P < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

Silibinin in combination with Aza inhibits the migratory potential of H1299 cells. H1299 cells were treated with DMSO (control) or silibinin (3.75 µM) alone or in combination with Aza (5 µM) for 48 hours. Migratory potential was examined using migration chambers either in continuous presence (A) or absence (B) (wash-out studies) of drug treatment of H1299 cells. Cell migration data shown are mean ± S.E.M. of three samples. #P < 0.05; *P < 0.001.

Fig. 4.

Silibinin in combination with TSA or Aza inhibits the invasiveness of H1299 cells. H1299 cells were treated with DMSO (control) or silibinin (3.75 µM) alone or in combination with either TSA (0.5 µM) (A) or Aza (5 µM) (B) for 48 hours. Effect of single/combination treatments on invasive potential of H1299 cells in the presence of continuous drug treatment was examined using invasion chambers. Cell invasion data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. of three samples. #P < 0.05; *P < 0.001.

Silibinin Enhances E-cadherin Expression and Concomitantly Reduces Zeb1 levels in NSCLC H322 and H358 Cells.

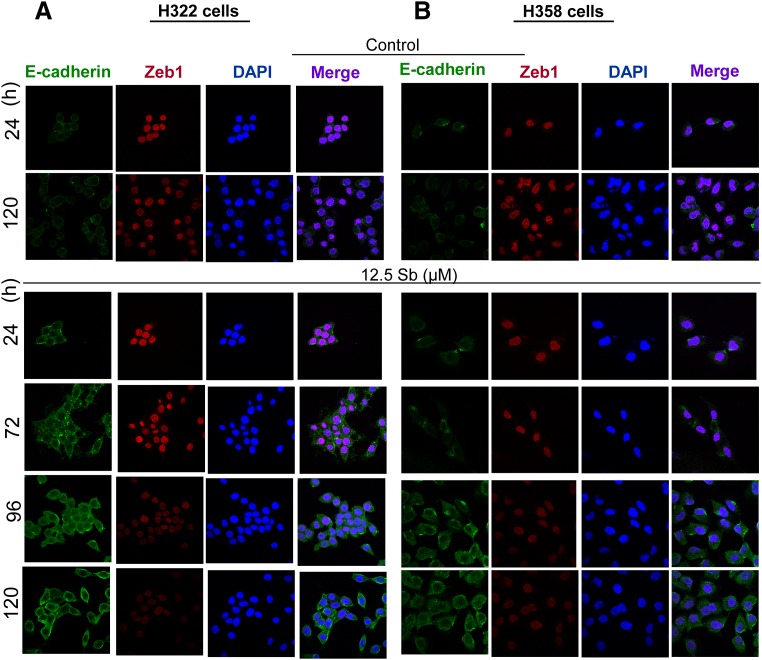

To further examine silibinin effects in NSCLC cell lines that differ vastly in their E-cadherin expression, we extended our studies in H322 and H358 cell lines, which are known to possess detectable E-cadherin levels (Witta et al., 2006). As observed by immunofluorescence, silibinin treatment at low dose (12.5 µM) resulted in a time-dependent (expression monitored as a function of time from 0 to 120 hours) increase in E-cadherin levels (Fig. 5, A and B). A concomitant decrease in nuclear levels of Zeb1 was also observed in this study, suggesting that an increase in E-cadherin levels by silibinin might be associated with a decrease in the levels of its transcriptional repressor, Zeb1, in NSCLC cell lines.

Fig. 5.

Silibinin treatment enhances E-cadherin and downmodulates Zeb1 expression in NSCLC H322 and H358 cells. H322 and H358 cells were treated with DMSO (control) or silibinin (12.5 µM) for 120 hours. Immunofluorescence staining is shown for E-cadherin (green)-, Zeb1 (red)-, and DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) in H322 (A) and H358 (B) cells. Cells were treated for 24–120 hours and subsequently processed as described in Materials and Methods.

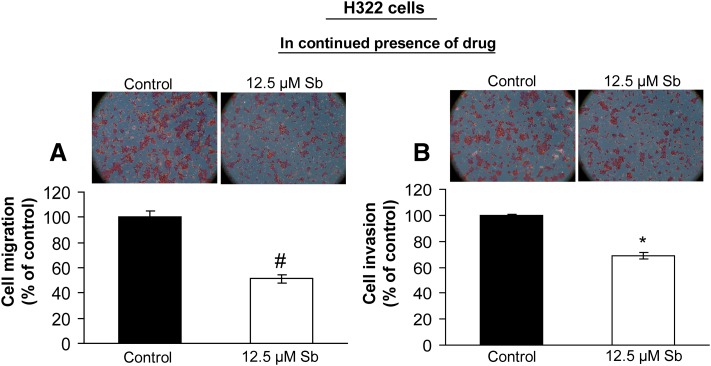

Silibinin Inhibits Cellular Migration and Invasion of NSCLC H322 Cells.

To decipher the biologic relevance of enhanced E-cadherin expression by silibinin in H322 cells, we next examined the migratory potential of these cells under similar treatment conditions, which showed E-cadherin re-expression. H322 cells treated with 12.5 µM silibinin for 96 hours were harvested, and then an equal number of live cells was suspended in the migration chambers. For 24 hours, cells were allowed to migrate toward the lower well containing RPMI media with 10% FBS. Thereafter, the migratory cells were fixed and stained. Quantitative analysis revealed that silibinin inhibited the migratory potential of H322 cells by 49% (P < 0.05; Fig. 6A). Similarly, silibinin also inhibited the invasion of H322 cells by 31% (P < 0.001; Fig. 6B), as determined by invasion assay. Since the dose of silibinin (12.5 µM) used in this study did not significantly alter viability of H322 cells (unpublished data), these findings established the anti-invasive and antimigratory properties of silibinin at the concentrations that not only enhanced E-cadherin levels but were also least cytotoxic to H322 cells.

Fig. 6.

Silibinin inhibits migration and invasion of H322 cells. H322 cells were treated with DMSO (control) or silibinin (12.5 µM) for 120 hours, and in the presence of continuous drug treatment, its effect on migratory (A) and invasive (B) potential of H322 cells was examined using migration and invasion chambers, respectively. Cell invasion/migration data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. of three samples. #P < 0.05; *P < 0.001.

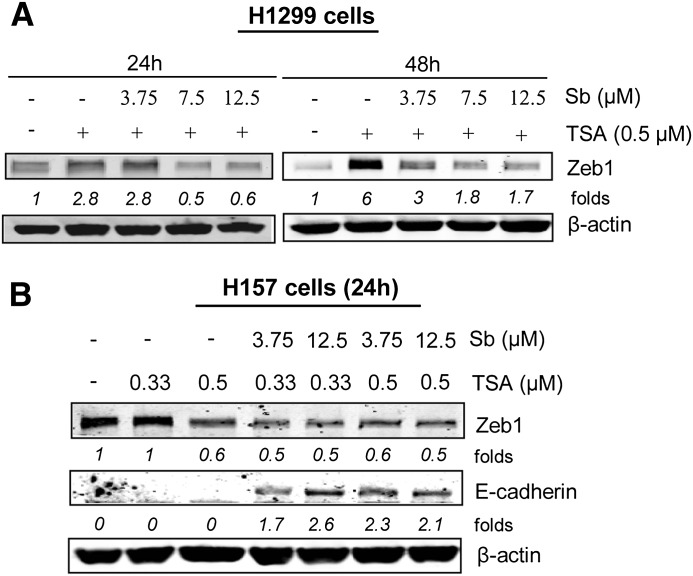

Silibinin Decreases Zeb 1 Protein Levels in NSCLC Cells.

Levels of E-cadherin and Zeb1 are inversely correlated and have been shown to be associated with resistance to EGFR-TKI in NSCLC cell lines (Witta et al., 2006, 2009). As shown earlier in Fig. 1, in presence of silibinin, both TSA and Aza treatments significantly restored E-cadherin protein levels. Under similar conditions, when H1299 cells were treated with TSA (0.5 µM) alone, it dramatically increased the protein levels of Zeb1 in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 7A). The combination of 3.75 µM silibinin dose with TSA (0.5 µM), although ineffective in reducing Zeb1 levels by 24 hours, showed significant effect in reducing Zeb1 levels by 48 hours. Interestingly, increasing the dose of silibinin to 7.5 and 12.5 µM with TSA (0.5 µM) combination for 24–48 hours further reduced the levels of this transcriptional repressor (Fig. 7A). Silibinin alone did not show any effects on Zeb1 levels in these studies (unpublished data). This finding indicates that silibinin in combination with HDACi possibly targets Zeb1 levels, while exerting its efficacy in re-expressing E-cadherin levels in H1299 cells. To further validate our findings, we next employed H157 cells, which do not exhibit an increase in E-cadherin (mRNA and protein) levels by HDACi due to their suppression by Zeb1 (Kakihana et al., 2009). We treated H157 cells to TSA (0.33–0.5 µM) alone or in combination with silibinin (3.75–12.5 µM) for 24 hours (Fig. 7B), and cell lysates were then analyzed for E-cadherin and Zeb1 protein levels. As illustrated in Fig. 7B, HDACi treatment did not alter the levels of both E-cadherin and Zeb1 at 0.33 µM dose in H157 cells. However, at 0.5 µM dose, it did cause a decrease in Zeb1 without affecting E-cadherin levels. More importantly, addition of low doses of silibinin synergized with the lower dose (0.33 µM) of HDACi in inducing E-cadherin expression together with a decrease in Zeb1 protein levels (Fig. 7B), although silibinin alone had no such effect (unpublished data). Together, these results suggest that whereas low doses of silibinin alone cannot re-express silenced E-cadherin in NSCLC cells, silibinin could synergize with HDACi such as TSA in upregulating E-cadherin levels possibly by a downmodulation of Zeb1, which is a major transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin.

Fig. 7.

Silibinin treatment reduces Zeb1 protein expression in NSCLC cells. (A) H1299 cells were treated with DMSO (control) or silibinin (3.75 µM) alone or in combination with either TSA (0.5 µM) or Aza (5 µM) for indicated time points. Cell lysates were prepared, and Zeb1 expression in total cell lysates was determined by immunoblotting. (B) H157 cells were treated with either DMSO (control) or TSA (0.33–0.5 µM) alone or in combination with silibinin (3.75–12.5 µM) for 24 hours. Cell lysates were prepared and E-cadherin and Zeb1 protein levels in total cell lysates were determined by immunoblotting.

Discussion

Downregulation or aberrant expression of E-cadherin is identified in several human cancers including colorectal, pancreas, lung, prostate, breast, etc., where poorly differentiated tumors contain reduced levels of E-cadherin (Beavon, 2000; Strathdee, 2002; Onder et al., 2008). Functional inactivation of E-cadherin occurs through varying genetic (irreversible) and epigenetic (reversible) alterations as well as transcriptional silencing of the human E-cadherin gene (CDH1) (Onder et al., 2008). Genetic mechanisms regulating E-cadherin expression include somatic mutations and loss of heterozygosity of the wild-type allele, which promotes tumorigenesis and induces tumor cell invasiveness. However, the incidence of E-cadherin mutations is rare in cancers, and alternative epigenetic mechanisms have been shown to play a preferential role in silencing its gene expression (Peinado et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005). The changes in epigenome result in reversible alterations in its gene expression patterns, which together with various other genetic abnormalities, contribute to the onset and progression of NSCLC (Nephew and Huang, 2003; Bowman et al., 2006). Akin to other malignacies, in NSCLC, loss of E-cadherin expression is a critical event associated with EMT and metastasis as well as cancer cell proliferation and drug resistance to apoptosis/anoikis (Onder et al., 2008; Zavadil et al., 2008; Kakihana et al., 2009).

E-cadherin is one of the predominant members of the cadherin family that is present within epithelial cells and localized on the basolateral membrane in the adherens junctions (Thiery, 2002; Zavadil et al., 2008; Chaffer and Weinberg, 2011). Cadherins (including E-cadherin) are a group of cell-adhesion molecules and are comprised of transmembrane glycoproteins responsible for maintaining cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion (Bremnes et al., 2002). Under normal conditions, E-cadherin has a functional role in physiologic processes such as embryonic morphogenesis and wound healing (Thiery, 2002; Liu et al., 2005). However, loss of this epithelial marker is crucial for EMT of the epithelial-derived solid tumors that acquire a mesenchymal phenotype resulting in increased tumor invasiveness and metastasis (Thiery, 2002; Onder et al., 2008; Tsuji et al., 2009; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). In NSCLC, studies have linked EMT and cancer progression to inflammation, since the production of inflammatory mediators (e.g., cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2) negatively regulates E-cadherin expression (Dohadwala et al., 2006). Apart from genetic and epigenetic events, downregulation of E-cadherin in human tumors also occurs via mechanisms like proteolytic cleavage (through matrix metalloproteinases), internalization/degradation of E-cadherin (through Hakai—an E3 ubiqutin ligase) (Le et al., 1999; Pece and Gutkind, 2002; Nawrocki-Raby et al., 2003). Transcriptional repressors (e.g., Zeb1) also regulate E-cadherin levels and induce EMT, promoting tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis (Spaderna et al., 2008; Drake et al., 2009; Gemmill et al., 2011). Specifically in NSCLC, Zeb1 has been shown to suppress the expression of E-cadherin by binding with its two 5′-CACCTG (E-box) sequences (Verschueren et al., 1999; Clarhaut et al., 2009). Zeb1 interaction with E-cadherin promoter has been shown to involve CtBP, a transcriptional corepressor protein that further enhances the binding of HDACs to the promoter regions of E-cadherin (Postigo and Dean, 1999). Knockdown of Zeb1 in NSCLC H661 cells has been shown to increase E-cadherin levels (Kakihana et al., 2009).Clinically, E-cadherin is used as a biomarker to predict responses to EGFR-TKI therapy in NSCLC patients (Witta et al., 2006; Soltermann et al., 2008). Taken together, the overall importance of this epithelial marker clearly suggests that studies are needed to identify the agents that could re-express epigenetically silenced E-cadherin levels in NSCLC.

In the present study, we focused our efforts on elucidating the effects of silibinin, a non-toxic photochemical with established anticancer activity against various epithelial malignancies including lung cancer (Singh et al., 2006; Tyagi et al., 2009; Mateen et al., 2010; Ramasamy et al., 2011; Tyagi et al., 2011), on the mechanisms that are responsible for silencing E-cadherin expression in NSCLC. Our results have clearly demonstrated that silibinin (at low noncytotoxic doses) in combination with TSA (an HDACi) or Aza (a DNMTi) strongly upregulates E-cadherin protein levels in H1299 cells. Concomitantly, at similar time points, cotreatment of TSA and silibinin drastically reduced Zeb1 levels, implicating the role of this transcriptional repressor in epigenetically suppressing the expression of E-cadherin in these NSCLC cells. By using H157 cells, we also found that the effect of low doses of silibinin combined with HDAC or DNMT inhibitor in upregulating E-cadherin expression might not entirely depend on the regulation of epigenetic enzymes (HDACs and DNMTs) but also possibly involves the downmodulation of Zeb1 levels. Our results in H322 and H358 cell lines further supported this notion, where silibinin treatment enhanced the cellular levels of E-cadherin while inversely reducing the nuclear Zeb1 levels. With regard to the biologic significance of these findings, silibinin alone and in combination with epigenetic drugs (HDAC or DNMT inhibitor) inhibited both invasion and migration of NSCLC cells. This finding suggests that following the drug treatments, an increased expression of E-cadherin was, in part, responsible for restricting the transformation of cells to a mesenchymal phenotype. Taken together, our results show the potential of silibinin alone and in combination with epigenetic drugs in downmodulating the expression of Zeb1 so as to restore E-cadherin expression and thereby efficiently inhibiting the invasion and migration of NSCLC cells. In summary, present findings are highly significant in establishing that although silibinin alone may be used to prevent EMT in early stages of the disease, the HDACi or DNMTi in combination with silibinin would be an effective treatment regimen to suppress NSCLC progression to more advanced (poorly differentiated) stages of this deadly malignancy, thereby advocating the clinical usefulness of this natural agent.

Abbreviations

- Aza

5′-Aza-deoxycytidine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DNMTs

DNA methyltransferases

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HDACs

histone deacetylases

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer cells

- TSA

Trichostatin A

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Mateen, Raina, Chan, R. Agarwal.

Conducted experiments: Mateen, Raina, C. Agarwal.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: C. Agarwal, Chan, R. Agarwal.

Performed data analysis: Mateen, Raina, R. Agarwal.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Mateen, Raina, Chan, R. Agarwal.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grants CA113876 and CA102514].

References

- Aghdassi A, Sendler M, Guenther A, Mayerle J, Behn CO, Heidecke CD, Friess H, Büchler M, Evert M, Lerch MM, et al. (2012) Recruitment of histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 by the transcriptional repressor ZEB1 downregulates E-cadherin expression in pancreatic cancer. Gut 61:439–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beavon IR. (2000) The E-cadherin-catenin complex in tumour metastasis: structure, function and regulation. Eur J Cancer 36 (13 Spec No):1607–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belinsky SA. (2004) Gene-promoter hypermethylation as a biomarker in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 4:707–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belinsky SA, Klinge DM, Stidley CA, Issa JP, Herman JG, March TH, Baylin SB. (2003) Inhibition of DNA methylation and histone deacetylation prevents murine lung cancer. Cancer Res 63:7089–7093 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bots M, Johnstone RW. (2009) Rational combinations using HDAC inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 15:3970–3977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman RV, Yang IA, Semmler AB, Fong KM. (2006) Epigenetics of lung cancer. Respirology 11:355–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremnes RM, Veve R, Hirsch FR, Franklin WA. (2002) The E-cadherin cell-cell adhesion complex and lung cancer invasion, metastasis, and prognosis. Lung Cancer 36:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. (2011) A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science 331:1559–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Varghese DS, Gillam MC, Peyton M, Modi B, Schiltz RL, Girard L, Martinez ED. (2012) Differential response of cancer cells to HDAC inhibitors trichostatin A and depsipeptide. Br J Cancer 106:116–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarhaut J, Gemmill RM, Potiron VA, Ait-Si-Ali S, Imbert J, Drabkin HA, Roche J. (2009) ZEB-1, a repressor of the semaphorin 3F tumor suppressor gene in lung cancer cells. Neoplasia 11:157–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denlinger CE, Ikonomidis JS, Reed CE, Spinale FG. (2010) Epithelial to mesenchymal transition: the doorway to metastasis in human lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 140:505–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohadwala M, Yang SC, Luo J, Sharma S, Batra RK, Huang M, Lin Y, Goodglick L, Krysan K, Fishbein MC, et al. (2006) Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent regulation of E-cadherin: prostaglandin E(2) induces transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and snail in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 66:5338–5345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake JM, Strohbehn G, Bair TB, Moreland JG, Henry MD. (2009) ZEB1 enhances transendothelial migration and represses the epithelial phenotype of prostate cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell 20:2207–2217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantin VR, Richon VM. (2007) Mechanisms of resistance to histone deacetylase inhibitors and their therapeutic implications. Clin Cancer Res 13:7237–7242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. (2010) Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 127:2893–2917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick BA, Helfrich BA, Coldren CD, Zheng D, Chan D, Bunn PA, Jr, Raben D. (2007) Epithelial to mesenchymal transition predicts gefitinib resistance in cell lines of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and non-small cell lung carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther 6:1683–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmill RM, Roche J, Potiron VA, Nasarre P, Mitas M, Coldren CD, Helfrich BA, Garrett-Mayer E, Bunn PA, Drabkin HA. (2011) ZEB1-responsive genes in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett 300:66–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144:646–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JP, Kantarjian HM. (2009) Targeting DNA methylation. Clin Cancer Res 15:3938–3946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone RW. (2002) Histone-deacetylase inhibitors: novel drugs for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 1:287–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Baylin SB. (2002) The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 3:415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakihana M, Ohira T, Chan D, Webster RB, Kato H, Drabkin HA, Gemmill RM. (2009) Induction of E-cadherin in lung cancer and interaction with growth suppression by histone deacetylase inhibition. J Thorac Oncol 4:1455–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TL, Yap AS, Stow JL. (1999) Recycling of E-cadherin: a potential mechanism for regulating cadherin dynamics. J Cell Biol 146:219–232 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SC, Jang IG, Kim YC, Park KO. (2000) The role of E-cadherin expression in non-small cell lung cancer. J Korean Med Sci 15:501–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YN, Lee WW, Wang CY, Chao TH, Chen Y, Chen JH. (2005) Regulatory mechanisms controlling human E-cadherin gene expression. Oncogene 24:8277–8290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks PA, Richon VM, Rifkind RA. (2000) Histone deacetylase inhibitors: inducers of differentiation or apoptosis of transformed cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:1210–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateen S, Raina K, Jain AK, Agarwal C, Chan D, Agarwal R. (2012) Epigenetic modifications and p21-cyclin B1 nexus in anticancer effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors in combination with silibinin on non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Epigenetics 10:1161–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateen S, Tyagi A, Agarwal C, Singh RP, Agarwal R. (2010) Silibinin inhibits human nonsmall cell lung cancer cell growth through cell-cycle arrest by modulating expression and function of key cell-cycle regulators. Mol Carcinog 49:247–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeran SM, Ahmed A, Tollefsbol TO. (2010) Epigenetic targets of bioactive dietary components for cancer prevention and therapy. Clin Epigenetics 1:101–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki-Raby B, Gilles C, Polette M, Bruyneel E, Laronze JY, Bonnet N, Foidart JM, Mareel M, Birembaut P. (2003) Upregulation of MMPs by soluble E-cadherin in human lung tumor cells. Int J Cancer 105:790–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal JW, Sequist LV. (2012) Complex role of histone deacetylase inhibitors in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:2280–2282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nephew KP, Huang TH. (2003) Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer initiation and progression. Cancer Lett 190:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira T, Gemmill RM, Ferguson K, Kusy S, Roche J, Brambilla E, Zeng C, Baron A, Bemis L, Erickson P, et al. (2003) WNT7a induces E-cadherin in lung cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:10429–10434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder TT, Gupta PB, Mani SA, Yang J, Lander ES, Weinberg RA. (2008) Loss of E-cadherin promotes metastasis via multiple downstream transcriptional pathways. Cancer Res 68:3645–3654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pece S, Gutkind JS. (2002) E-cadherin and Hakai: signalling, remodeling or destruction? Nat Cell Biol 4:E72–E74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H, Portillo F, Cano A. (2004) Transcriptional regulation of cadherins during development and carcinogenesis. Int J Dev Biol 48:365–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo AA, Dean DC. (1999) ZEB represses transcription through interaction with the corepressor CtBP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:6683–6688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy K, Dwyer-Nield LD, Serkova NJ, Hasebroock KM, Tyagi A, Raina K, Singh RP, Malkinson AM, Agarwal R. (2011) Silibinin prevents lung tumorigenesis in wild-type but not in iNOS-/- mice: potential of real-time micro-CT in lung cancer chemoprevention studies. Clin Cancer Res 17:753–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robey RW, Chakraborty AR, Basseville A, Luchenko V, Bahr J, Zhan Z, Bates SE. (2011) Histone deacetylase inhibitors: emerging mechanisms of resistance. Mol Pharm 8:2021–2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmalhofer O, Brabletz S, Brabletz T. (2009) E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and ZEB1 in malignant progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 28:151–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrump DS. (2009) Cytotoxicity mediated by histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer cells: mechanisms and potential clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res 15:3947–3957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shames DS, Girard L, Gao B, Sato M, Lewis CM, Shivapurkar N, Jiang A, Perou CM, Kim YH, Pollack JR, et al. (2006) A genome-wide screen for promoter methylation in lung cancer identifies novel methylation markers for multiple malignancies. PLoS Med 3:e486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Deep G, Chittezhath M, Kaur M, Dwyer-Nield LD, Malkinson AM, Agarwal R. (2006) Effect of silibinin on the growth and progression of primary lung tumors in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:846–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltermann A, Tischler V, Arbogast S, Braun J, Probst-Hensch N, Weder W, Moch H, Kristiansen G. (2008) Prognostic significance of epithelial-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-epithelial transition protein expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14:7430–7437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaderna S, Schmalhofer O, Wahlbuhl M, Dimmler A, Bauer K, Sultan A, Hlubek F, Jung A, Strand D, Eger A, et al. (2008) The transcriptional repressor ZEB1 promotes metastasis and loss of cell polarity in cancer. Cancer Res 68:537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee G. (2002) Epigenetic versus genetic alterations in the inactivation of E-cadherin. Semin Cancer Biol 12:373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Xu W, Wang Q, Xiao W, Xu R. (2009) Potential of DNMT and its Epigenetic Regulation for Lung Cancer Therapy. Curr Genomics 10:336–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiery JP. (2002) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2:442–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EW, Newgreen DF, Tarin D. (2005) Carcinoma invasion and metastasis: a role for epithelial-mesenchymal transition? Cancer Res 65:5991–5995, discussion 5995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji T, Ibaragi S, Hu GF. (2009) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell cooperativity in metastasis. Cancer Res 69:7135–7139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi A, Agarwal C, Dwyer-Nield LD, Singh RP, Malkinson AM, Agarwal R. (2011) Silibinin modulates TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma mediated signaling to regulate COX2 and iNOS expression in tumorigenic mouse lung epithelial LM2 cells. Mol Carcinog 51:832–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi A, Singh RP, Ramasamy K, Raina K, Redente EF, Dwyer-Nield LD, Radcliffe RA, Malkinson AM, Agarwal R. (2009) Growth inhibition and regression of lung tumors by silibinin: modulation of angiogenesis by macrophage-associated cytokines and nuclear factor-kappaB and signal transducers and activators of transcription 3. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2:74–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschueren K, Remacle JE, Collart C, Kraft H, Baker BS, Tylzanowski P, Nelles L, Wuytens G, Su MT, Bodmer R, et al. (1999) SIP1, a novel zinc finger/homeodomain repressor, interacts with Smad proteins and binds to 5′-CACCT sequences in candidate target genes. J Biol Chem 274:20489–20498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witta SE, Dziadziuszko R, Yoshida K, Hedman K, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr, Hirsch FR. (2009) ErbB-3 expression is associated with E-cadherin and their coexpression restores response to gefitinib in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol 20:689–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witta SE, Gemmill RM, Hirsch FR, Coldren CD, Hedman K, Ravdel L, Helfrich B, Dziadziuszko R, Chan DC, Sugita M, et al. (2006) Restoring E-cadherin expression increases sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 66:944–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yauch RL, Januario T, Eberhard DA, Cavet G, Zhu W, Fu L, Pham TQ, Soriano R, Stinson J, Seshagiri S, et al. (2005) Epithelial versus mesenchymal phenotype determines in vitro sensitivity and predicts clinical activity of erlotinib in lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 11:8686–8698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavadil J, Haley J, Kalluri R, Muthuswamy SK, Thompson E. (2008) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res 68:9574–9577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Peyton M, Xie Y, Soh J, Minna JD, Gazdar AF, Frenkel EP. (2009) Histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin enhances anti-tumor effect of erlotinib in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines. J Thorac Oncol 4:161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Fields CR, Su N, Pan YX, Robertson KD. (2007) Pharmacologic inhibition of epigenetic modifications, coupled with gene expression profiling, reveals novel targets of aberrant DNA methylation and histone deacetylation in lung cancer. Oncogene 26:2621–2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zöchbauer-Müller S, Fong KM, Virmani AK, Geradts J, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. (2001) Aberrant promoter methylation of multiple genes in non-small cell lung cancers. Cancer Res 61:249–255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]