Abstract

Purpose

Ureteral cancer is a rare entity. Typical symptoms are painless hematuria as well as flank pain. Bone metastasis of ureteral cancer can occur in nearby bone structures, such as the spine, pelvis, and hip bone. Distal bone metastasis, such as that in the calcaneus bone, however, is rare.

Case report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the orthopedic clinic at the university hospital with a 3-month history of left heel pain. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her foot demonstrated a calcaneal lytic lesion. A biopsy of the lytic lesion showed urothelial carcinoma with squamous differentiation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed left hydronephrosis and an obstructive mass in the left ureter, at the iliac crossing. The patient received combined therapy that included local radiation, bisphosphonate, and chemotherapy, with complete resolution of her cancer-related symptoms. However, she eventually died from the progressive disease, 20 months after the initial diagnosis.

Conclusion

This case highlights the rare presentation of ureter cancer with an initial presentation of foot pain, secondary to calcaneal metastasis. Multimodality therapy provides effective palliation of symptoms and improved quality of life. We also reviewed the literature and discuss the clinical benefits of multidisciplinary cancer care in elderly patients.

Keywords: urothelial carcinoma, elderly, calcaneal acrometastasis, multimodality therapy, chemotherapy, radiation

Introduction

Ureteral cancer is rare. Ureteral urothelial carcinoma represents about 25% of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinomas.1–3 Batata et al2 found only 2.5% of 2566 primary urothelial carcinomas to be ureteral cancers. Of the 41 invasive ureteral cancers in Batata’s study, 92.7% were urothelial carcinomas.2 Williams and Mitchell3 found a 1:54 ratio of cases of ureteral carcinoma to cases of bladder carcinoma and reported that twice as many men had ureteral carcinoma as did women. Patients with upper urinary tract cancers usually present symptoms of gross hematuria, but flank pain, dysuria, and frequency of urination are other less common presentations.4–5

Bone metastasis from cancer can occur in nearby bone structures, such as the spine, pelvis, and hip bone.6 In contrast, acrometastases, or metastases to the bones of the hand or foot, are rare.7–14 Overall, studies show either a 2:1 or 3:1 ratio of hand and foot metastases.9–11 Of foot metastases, Zindrick et al12 found that 50% involve the talus, and 23% are located in the calcaneus. Acrometastases to the foot is most commonly derived from primary carcinomas in the lung, kidney, colon, and breast, but other sources include the bladder, uterus, and prostate.10,13,14 Due to the rarity of acrometastases, misdiagnosis is not uncommon and often causes delays in proper diagnosis and treatment.9 Herein, we present the first case of ureteral urothelial carcinoma in an elderly woman who initially presented with calcaneal metastasis.

Case report

In November 2010, an 82-year-old Caucasian female presented at the orthopedic clinic at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) with a 3-month history of left heel pain, for which she had been treated by a primary care physician with anti-inflammatories, without relief. She had no history of local injury or trauma; she also denied any hematuria. Her medical and family histories were significant for hypertension. Otherwise, she had been in good health and highly functional for her age. An X-ray of her left foot displayed radiolucency of the calcaneus (Figure 1). She was then evaluated by an orthopedic surgeon, and an orthopedic controlled ankle motion (CAM) boot and pain medications were prescribed for symptomatic treatment. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a left calcaneal lesion, and metastatic disease was suspected. A biopsy of the calcaneal lesion revealed metastatic urothelial-cell carcinoma with squamous differentiation (Figure 2). Further workup, including a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis, showed left hydronephrosis and an obstructive mass in the left ureter, at the iliac crossing (Figure 3). A technetium-99m bone scan revealed increased radioactive uptake in the left calcaneus (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Radiograph of the left foot, demonstrating a large lytic lesion and destruction of the calcaneus, the cuboid, and the fifth metatarsal.

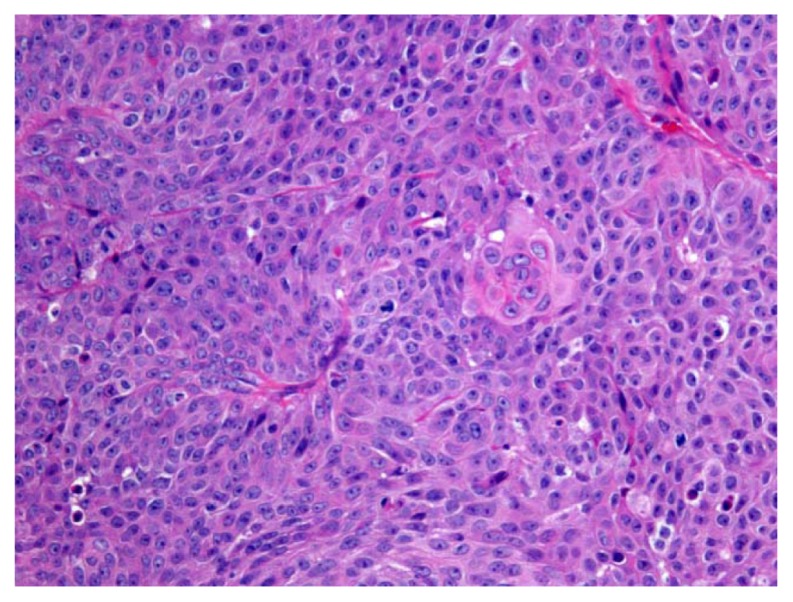

Figure 2.

Left calcaneal biopsy specimen showing urothelial carcinoma with squamous differentiation.

Notes: Hematoxylin and eosin; magnification 100×.

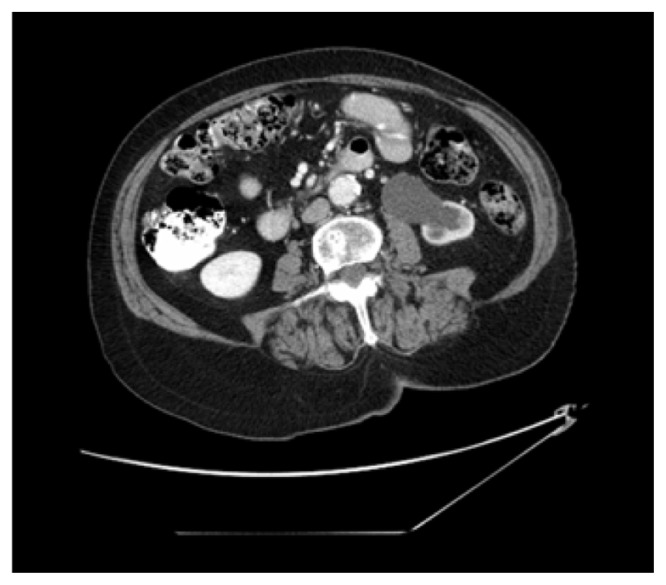

Figure 3.

Abdominal and pelvic CT scan revealing a left hydronephrosis with renal cortical atrophy and an obstructing mass at the iliac crossing of the left ureter.

Abbreviation: CT, computed tomography.

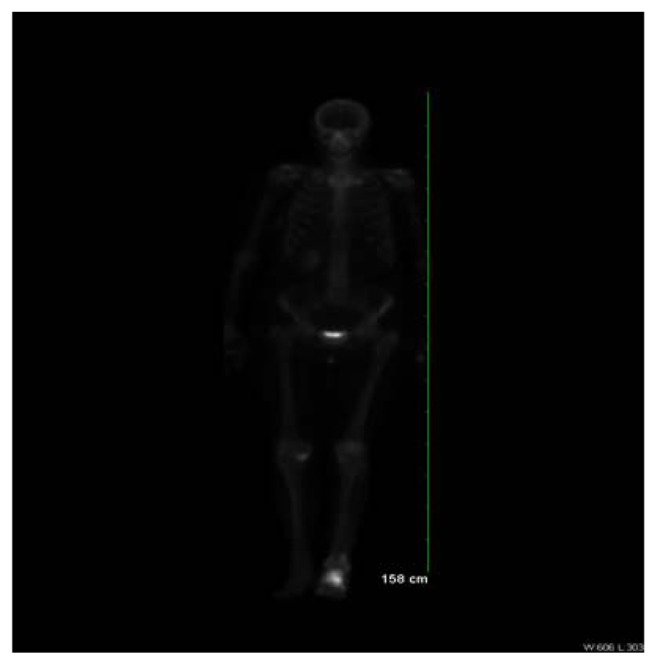

Figure 4.

Technetium-99m MDP whole body bone scan displaying intense increased radioactive uptake in the left calcaneus with mild increased radioactive uptake in the proximal and distal left fibula with some extension into the shaft.

Abbreviation: MDP, methylene-diphosphonate.

Following the results of the bone scan, the patient was referred to a medical and radiation oncology service for further disease management. She received palliative radiation to the metastatic site, followed by a five-cycle course of chemotherapy with gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8, and carboplatin at area under the curve (AUC) 4 on day 1 (given after gemcitabine) and every 21 days for four cycles. Additionally, she received intravenous zoledronic acid (ZOMETA®; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp, Basel, Switzerland) monthly for her bone metastasis. After 3 months of treatment, the patient regained functional status and ambulation, and began volunteer work again at a local gift shop.

In July 2011, the patient presented to her medical oncologist with new onset of dysuria and painful vaginal discharge. A pelvic examination revealed no obvious pathology. Urine cytology was negative for malignancy. However, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed a urethral mass with an elevated standardized uptake value. Subsequently, she was seen by an urologist. A cystoscopy found a vaginal mass around the urethra. A biopsy of the urethral mass revealed a high-grade metastatic urothelial carcinoma with lymphovascular-space invasion, consistent with the morphology of the previous biopsy of the calcaneal lytic lesion. Subsequently, she was treated, using second-line chemotherapy, with five doses of nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane®; Celgene Corp, Summit, NJ, USA) 260 mg/m2 intravenously every 3 weeks; additionally, she received palliative radiation to the urethral mass for pain control. At the time of restaging, the tumor size and pain level had decreased significantly as a result of treatment.

In February 2012, after a 4-month break from chemotherapy, during which the patient was pain-free and very active, the patient returned to the oncology clinic with a new complaint of a 1-week history of pain in the left buttock. A restaging PET scan showed metastatic disease progression in the pelvic bone and sacral areas as well as new pulmonary and hepatic metastases. She received three doses of third-line chemotherapy, pemetrexed (ALIMTA®; Eli Lilly and Co, Indianapolis, IN, USA) 500 mg/m2, every 3 weeks and palliative radiation to the pelvic and sacral metastases. She had significant pain relief, even to the point of completely discontinuing the fentanyl patch prescribed for pain control. Still, her disease unfortunately progressed several months later. She went on hospice care and died in August 2012.

Discussion

While bone metastases, or metastatic bone disease, are common, as demonstrated by Abrams et al,6 who found bone metastases in 27.2% of 1000 patients with malignant cancer, acrometastasis is a rare phenomenon. Hattrup et al15 found only ten cases of foot or ankle metastasis in more than 75,000 patients with primary tumors. Similarly, Wu and Guise8 found only four patients with foot acrometastasis in a total of 41,833 cancer patients. Often times, the primary tumor is not recognized before the occurrence of acrometastasis, as exemplified in our case. Hattrup et al15 found that nine of 17 patients with acrometastasis demonstrated foot or ankle pain as their chief complaint without a previously known primary malignancy. Gall et al7 emphasize that a common complaint of foot pain is a possible indicator for an unknown cancer. Thus, an occult cancer should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis of foot pain. Our case is the first reported case with foot pain/acrometastases as the initial symptom presentation of an occult ureteral cancer.

Unfortunately, due to the rarity of acrometastasis and the numerous diseases and conditions that it imitates, misdiagnoses and delays in diagnosis are not uncommon.14 In the previously mentioned study by Hattrup et al,15 five of the nine unknown primary malignancy cases had delayed diagnoses that averaged 6.4 months. Similarly, Healey et al9 found five of 29 acrometastasis cases that were initially misdiagnosed. In our case, the patient was properly diagnosed within 3 weeks of presentation at our facility and within 4 months of the patient’s initial recognition of pain.

The prognosis and survival rates of acrometastases are poor. Hattrup et al15 calculated a mean survival rate of 12.3 months for 20 patients with acrometastasis. Maheshwari et al14 found a mean survival rate of 14.8 months in their study, with a range of 1 to 54 months, for patients with acrometastases. Our patient survived 20 months after the initial presentation of symptoms to the clinical staff at UNMC.

Given the poor prognosis for acrometastases, the importance of a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach is necessary for prompt diagnosis and effective treatment. Appropriate radiographic imaging, such as X-ray, MRI, and bone and CT scans, is a critical part of the investigation of the cause of the foot pain. Ultimately, a tumor-tissue biopsy is needed for establishing the histological diagnosis. In our case, the multimodality treatment that the patient received consisted of chemotherapy and radiation as well as bisphosphonate treatment. A multidisciplinary team, consisting of a primary care physician, an orthopedic surgeon, a medical oncologist, a urologist, and a radiation specialist, successfully communicated and worked together in order to properly and promptly diagnose and manage treatment of this case.

Urothelial ureteral cancer is a disease that disproportionately affects the elderly.1 The treatment of elderly patients with metastatic urothelial cancer is challenging due to a lack of prospective data regarding the appropriate disease management for this population. The standard treatment for ureteral urothelial cancer consists of nephroureterectomy, with removal of the bladder cuff.4 In 2010, Labanaris et al16 demonstrated the efficacy and safety of nephroureterectomy in elderly patients over the age of 80. Chemotherapy treatment for ureteral urothelial tumors involves similar treatment to that of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, due to the similar histology of these two diseases.4 Thus, gemcitabine-cisplatin combination therapy has become the standard of care for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma, good functional status, and proper kidney function.17 Palliative radiation can provide significant relief, with 83% of patients receiving partial pain relief and 54% receiving complete pain relief.18 Elderly patients have an increased risk of side effects from chemotherapy, due to factors such as decreased organ function, comorbidities, and polypharmacy.19 However, the elderly can still benefit as much from chemotherapy as can younger patients.20–22 In gemcitabine combination therapy, carboplatin can be effectively substituted for cisplatin in elderly patients with poor renal function, although carboplatin-based chemotherapy is less effective than cisplatin-based chemotherapy.23,24

When treating the elderly with cancer, the distinction between chronological and biological age is important to consider in order to provide the best care for individual patients.20 Our patient demonstrated a good functional status and little comorbidity, which justified the use of chemotherapy despite her advanced age. While our patient did experience side effects, such as mild neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy, chemotherapy was otherwise well tolerated, with the occasional need for dose reduction. While the limitation of case report is obvious, our case underscores the urgent need for clinical trials designed specifically for elderly cancer patients, to determine the optimal therapy for this population.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of ureteral urothelial carcinoma with an initial presentation of foot pain/calcaneal metastasis. This rare metastasis should be included as a possibility in the differential diagnosis for foot pain, to prevent delays in diagnosis and treatment. Our case also highlights the benefits of multidisciplinary cancer care and multimodality treatment for an elderly patient.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the primary care physician, the urologist, the pathologist, and the radiation oncologist who participated in the care of our patient. JR was a student scholar working with JW during the study period.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Munoz JJ, Ellison LM. Upper tract urothelial neoplasms: incidence and survival during the last 2 decades. J Urol. 2000;164(5):1523–1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batata MA, Whitmore WF, Hilaris BS, Tokita N, Grabstald H. Primary carcinoma of the ureter: a prognostic study. Cancer. 1975;35(6):1626–1632. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197506)35:6<1626::aid-cncr2820350623>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams CB, Mitchell JP. Carcinoma of the ureter – a review of 54 cases. Br J Urol. 1973;45(4):377–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1973.tb12175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godoy G, Lerner SP. Upper tract tumors. In: Scardino PT, Linehan WM, Zelefsky MJ, et al., editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Genitourinary Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. pp. 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall MC, Womack S, Sagalowsky AI, Carmody T, Erickstad MD, Roehrborn CG. Prognostic factors, recurrence, and survival in transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: a 30-year experience in 252 patients. Urology. 1998;52(4):594–601. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams HL, Spiro R, Goldstein N. Metastases in carcinoma; analysis of 1000 autopsied cases. Cancer. 1950;3(1):74–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<74::aid-cncr2820030111>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gall RJ, Sim FH, Pritchard DJ. Metastatic tumors to the bones of the foot. Cancer. 1976;37(3):1492–1495. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197603)37:3<1492::aid-cncr2820370335>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu KK, Guise ER. Metastatic tumors of the foot. South Med J. 1978;71(7):807–808. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197807000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Healey JH, Turnbull AD, Miedema B, Lane JM. Acrometastases. A study of twenty-nine patients with osseous involvement of the hands and feet. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(5):743–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libson E, Bloom RA, Husband JE, Stoker DJ. Metastatic tumours of bones of the hand and foot. A comparative review and report of 43 additional cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1987;16(5):387–392. doi: 10.1007/BF00350965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarup S, Grant AC. Acrometastasis from a transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Orthopedics. 2000;23(2):161–162. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20000201-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zindrick MR, Young MP, Daley RJ, Light TR. Metastatic tumors of the foot: case report and literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;170:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lombardi RM, Amadio PC. Acrometastases. In: Sim FH, editor. Diagnosis and Management of Metastatic Bone Disease. New York: Raven Press; 1988. pp. 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maheshwari AV, Chiappetta G, Kugler CD, Pitcher JD, Jr, Temple HT. Metastatic skeletal disease of the foot: case reports and literature review. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(7):699–710. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hattrup SJ, Amadio PC, Sim FH, Lombardi RM. Metastatic tumors of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle. 1988;8(5):243–247. doi: 10.1177/107110078800800503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labanaris AP, Zugor V, Labanaris AP, Elias P, Kühn R. Radical nephrectomy and nephroureterectomy in patients over 80 years old. Int Braz J Urol. 2010;36(2):141–148. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382010000200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(17):3068–3077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong D, Gillick L, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases: final results of the Study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer. 1982;50(5):893–899. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820901)50:5<893::aid-cncr2820500515>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Repetto L. Greater risks of chemotherapy toxicity in elderly patients with cancer. J Support Oncol. 2003;1(4 Suppl 2):S18–S24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balducci L. The geriatric cancer patient: equal benefit from equal treatment. Cancer Control. 2001;8(Suppl 2):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bamias A, Efstathiou E, Moulopoulos LA, et al. The outcome of elderly patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma after platinum-based combination chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(2):307–313. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castagneto B, Zai S, Marenco D, et al. Single-agent gemcitabine in previously untreated elderly patients with advanced bladder carcinoma: response to treatment and correlation with the comprehensive geriatric assessment. Oncology. 2004;67(1):27–32. doi: 10.1159/000080282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shannon C, Crombie C, Brooks A, Lau H, Drummond M, Gurney H. Carboplatin and gemcitabine in metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium: effective treatment of patients with poor prognostic features. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(7):947–952. doi: 10.1023/a:1011186104428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellmunt J, Ribas A, Eres N, et al. Carboplatin-based versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy in the treatment of surgically incurable advanced bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80(10):1966–1972. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971115)80:10<1966::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]