Abstract

Cardiovascular disease represents the major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus. Studies by us and others have implicated increased flux via aldose reductase (AR) as a key player in mediating diabetic complications, including cardiovascular complications. Data suggest that increased flux via AR in diabetics perpetuates increased injury after myocardial infarction, accelerates atherosclerotic lesion formation, and promotes restenosis via multiple mechanisms. Most importantly, studies have shown that increased generation of reactive oxygen species due to flux via AR has been a common feature in animal models of diabetic cardiovascular disease. Taken together, these considerations place AR in the center of biochemical and molecular stresses that characterize the cardiovascular complications of diabetes. Stopping AR-dependent signaling may hold the key to interrupting cycles of cellular perturbation and tissue damage in diabetic cardiovascular complications.

Keywords: Advanced glycation end products, Aldose reductase, Aldose reductase inhibitors, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular complications, Diabetes, hyperglycemia, ischemia reperfusion, Oxidative stress, Polyol pathway

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes and its cardiovascular complications such as atherosclerosis, restenosis, and cardiac ischemia are major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The mechanisms that mediate the aberrant response to vascular injury remain to be fully clarified in these disease processes. Strident advances in molecular genetics made it possible to knock-in or knock-out specific genes in animal models and, thereby, to study functional significance of those genes in a disease perspective [1]. Increasing evidence supports a key role for hyperglycemia-mediated reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in diabetic cardiovascular complications [2–8]. High levels of glucose are metabolized through Aldose Reductase (AR) and Sorbitol Dehydrogenase (SDH) to generate high intracellular levels of polyols and fructose. AR reduces glucose to sorbitol in the presence of NADPH, and SDH oxidizes sorbitol to fructose using NAD+. AR is ~35,900 Daltons cytoplasmic enzyme with a triose phosphate isomerase structural motif that contains ten peripheral alpha-helical segments surrounding an inner barrel of beta-pleated sheet segments [9]. AR (E.C. 1.1.1.21; AKR1B1, ALD2) is a member of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily [10] and has been extensively studied [11, 12] in relation to diabetes and its secondary complications pertaining to the cardiovascular system, kidney and the eyes.

The primary focus of this review will be on AR, the rate limiting enzyme of the polyol pathway that channels the entry of excess glucose into the cytosol of cardiovascular cells, including cardiomyoctes and vascular cells. We will present evidences that polyol flux through AR plays a central role in mediating diabetic cardiovascular complications, in part via ROS, with special reference to ischemia-reperfusion injury, atherosclerosis, and restenosis. Finally we will discuss the clinical application of various AR inhibitors, their beneficial role in reducing these cardiovascular complications in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects.

AR AND HYPERGLYCEMIA IN CARDIOVASCULAR CELLS

Chronic elevation of glucose affects many biological processes in cardiovascular cells. The metabolic homeostasis of these cardiovascular cells is impacted by a number of key pathways - including the polyol pathway, the cytoplasmic redox state, the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway, the glucosamine biosynthesis pathway and production of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [3, 13–16]. The increased activation of these specific pathways in hyperglycemia has specific functional repercussions. While in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells, chronic hyperglycemia causes enhanced glycolytic and mitochondrial oxidative metabolism; [7] in rat chronic hyperglycemia inhibits glycolytic rates and alters substrate use of cardiovascular cells [17]. Excess glucose levels and/or the metabolic flux [14] associated with these cells leads to generation of excess intracellular superoxide and other mediators of oxidative stress, a phenomenon which is acknowledged to play an important role in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications [3, 18–20]. The primary source(s) of electrons that fuel superoxide production is still controversial and are likely to be multi-factorial. Williamson and colleagues demonstrated a strong link between polyol pathway flux and the ratio of free cytosolic NADH to NAD+, a factor critical to vascular function and redox homeostasis [21, 22]. There are a number of interactions of the polyol pathway and its coenzymes with other metabolic pathways. Cheng and Gonzalez [23] demonstrated that increased turnover of NADPH due to flux through AR competed with the antioxidant enzyme glutathione (GSH) reductase for the same pool of cytoplasmic NADPH. As detoxification of ROS and other peroxides are dependent on the availability of NADPH, any alteration and imbalance might lead to inability of the cells to protect against oxidative stress. The metabolic scenario created through depletion of NADPH and accumulation of reduced NAD leads to imbalance in the redox state creating a hypoxia-like response, or “pseudohypoxia” [21]. Increased NADH due to elevated activity of the polyol pathway leads to increased synthesis of diacylglycerol (DAG), which in turn activates phospholipase C and the protein kinase C family [3]. DAG-dependent activation has been shown to play critical role in smooth muscle cell proliferation induced by high glucose [24].

AR AND ATHEROSCLEROSIS

An important question has thus been to study the role of AR in cardiovascular disease. In recent years, there have been few studies which highlighted the role of AR in atherosclerosis. Inherently, mice display much lower levels of AR compared to human subjects. Hence, to develop a more relevant means to test the role of AR in murine models, a transgenic mouse line in which human AR (hAR) was expressed via a histocompatibility gene promoter [25] was used to study the effect of diabetes to accelerate atherosclerosis. This transgene had AR activity comparable to that of humans. Upon crossing onto the atherogenic LDL receptor null background, the hAR transgene had an effect on acceleration of atherosclerosis particularly in streptozotocin induced diabetic mice [26]. In contrast, no significant effect of the hAR transgene was observed in non-diabetic mice. In parallel with increased atheroslerosis, the diabetic mice overexpressing hAR in the LDL receptor null background showed a decrease in anti-oxidant defenses, as observed by alteration of GSH. On the contrary, expression of hAR in high fat diet-fed mice with mild insulin resistance without hyperglycemia had no effect on vascular lesions, at least over the time course studied [27]. Thus, plausible evidence was shown to substantiate the fact that hyperglycemia is needed and might need to be sufficiently increased to provide substrate for AR in the acceleration of atherosclerosis.

In contrast, another study demonstrated increased lesion area in diabetic and non-diabetic AR knockout mice in apoE null background [28]. The lesions showed increased presence of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), an oxidative marker which correlated with the lesion size and this was attributed to defective clearance of toxic phospholipid aldehydes because of the AR deficient genotype. The lesions were shown to be highly stable as demonstrated by more collagen [28]. These contrasting reports lead to a paradox on the precise role of AR in cardiovascular disease. A plethora of questions arose regarding the ambiguity; wherein it was assumed either association of compensatory regulation in the AR null mice lead to alteration in vascular function or genetic over-expression simulates the disease pathophysiology. Emerging studies on the impact of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH-2) in detoxifying 4-HNE [29] adds further complexity to the interpretation of lipotoxoic aldehyde levels in AR overexpressing and AR null mice. Thus, further investigation of the interplay between AR and ALDH-2 in detoxifying 4-HNE and other lipotoxic aldehydes in hAR and AR null mice is critical to resolving these contrasting findings.

Our recent study has elucidated that over-expression of hAR in apoE null mice made diabetic by streptozotocin is proatherogenic and that expression specifically in endothelial cells leads to increased pathology [30]. However, the highlight of the study was that use of a competitive inhibitor that reduces AR activity was found to reduce the lesion size significantly [30]. Overexpression of hAR led to endothelial dysfunction and increased expression of VCAM-1 and MMP-2. Diabetic hAR overexpressing mice aortic rings demonstrated decreased acetylcholine mediated endothelial vasorelaxation compared to the wild-type aorta. Endothelial cell specific overexpression of hAR imparted a similar effect [30]. In support of this study, other pharmacological studies of AR inhibition have shown improvement in acetylcholine induced relaxation of diabetic aorta in various murine models. These findings suggest that increased activity of the AR pathway in hyperglycemia is partly responsible for the abnormal endothelium-dependent relaxation in the diabetic blood vessel.

AR expression has been reported in CD68+ cells (monocytes/macrophages) in human atherosclerotic plaque macrophages [31]. Monocyte-derived macrophages isolated from human blood when incubated with oxLDL demonstrated increased AR gene expression and activity along with increased ROS. Inhibition of AR in these oxLDL-stimulated cells attenuated ROS generation. Similarly, endothelial function was improved and VCAM-1 and MMP-2 expression reduced by both pharmacological inhibition and targeted silencing of AR in ECs exposed to high oxLDL [30].

An additional mechanism proposed for AR-mediated accelerated atherosclerosis is through advanced glycation end (AGE) linked RAGE activation. In support of this, studies in smooth muscle cells incubated with AGE-bovine serum albumin (AGE-BSA) resulted in greater increments of ICAM-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), migration and monocyte adhesion in AR transgenic versus wild-type cells [32]. These AGE adduct mediated increases were suppressed either by pharmacological inhibition of AR using ARI (zopolrestat) or molecular intervention using AR antisense oligonucleotides [33].

AR IN THE MYOCARDIUM AND THE ROLE IN ISCHEMIA

Glucose flux via AR is known to be increased under ischemic conditions, irrespective of the presence or absence of diabetes [17, 34–37]. Several studies using isolated perfused hearts and transient occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery in mice and rats have shown enhanced glucose flux via AR [34, 35, 38, 39]. Pharmacological intervention using AR inhibitors reduced ischemic injury, attenuated ROS generation, improved glycolysis, increased ATP levels, and maintained the ionic balance (sodium and calcium homeostasis) in the heart [34, 35, 38, 39].

Studies performed in transgenic mice expressing human-relevant levels of AR showed increased cardiac injury during ischemia/reperfusion [35]. A more direct relationship of glucose flux via AR to oxidative stress was demonstrated in cardiac injury. AR influenced the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) and was linked to generation of hydrogen peroxide and diminished antioxidant status as measured by GSH. Antioxidants or ARIs significantly reduced generation of ROS and inhibited MPTP opening in AR transgenic mitochondria after I/R [39]. Taken together, these studies implicate AR and ROS through the AR pathway as a key player in mediating I/R injury in the heart. In rabbit hearts subjected to I/R injury inhibition of AR was protective [40], although it has also been reported to abolish the cardioprotective effects of ischemic preconditioning [41]. Others [42] showed increases in AR activity during ischemia consistent with our earlier publication [34]; on the contrary they were unable to demonstrate cardio-protection with ARIs in a glucose-perfused isolated rat heart ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) model. Though reasons for these contrasting findings are not clear, it may be speculated that model-dependent variations and substrate availability during ischemia may underlie the apparent differences.

4-HNE accumulates during I/R. AR has been proposed to detoxify these aldehydes that accumulate during I/R. While studies from Chen et al. show reduction of 4-HNE by activation of ALDH2 and protection of hearts from ischemic damage, [29] other reports, including studies from our group, [43] have demonstrated increased injury, poor functional recovery and increased oxidative stress after myocardial I/R in mice hearts overexpressing AR. Further, mice expressing human AR displayed greater injury and higher malonyldialdehyde (MDA) content with reduced GSH [39]. Studies in rodent hearts subjected to I/R showed increases in the polyol pathway activity associated with oxidative damage. On the contrary, AR null mice were reported to have reduced oxidative stress and protection against ischemic injury [44]. In rat hearts subjected to I/R, increases in polyol pathway activity exacerbated oxidative damage [45]. Furthermore, AR inhibition in animals did not cause increases in lipid peroxidation products such as MDA [45, 46–49]. However further studies on comprehensive measurements of 4-HNE and the role of ALDH2 will enable us to understand the role of AR as a potential detoxifying enzyme in ischemic hearts.

Changes in AR expression have been demonstrated in failing hearts during diabetes. Type 2 diabetic rat hearts show increased substrate flux via AR and SDH [50]. Studies in dogs have linked changes in AR expression to progression of pacing induced heart failure [51]. In humans, increases in AR expression were observed in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and diabetic cardiomyopathy [52]. These reports underscore the importance of AR in the etiology of heart failure.

AR AND VASCULAR INJURY

AR is implicated in proliferation of smooth muscle cell (SMC) growth in a model of vascular repair. Intervention of AR prevents SMC growth in culture and in situ in balloon-injured carotid arteries [24, 53–57]. Increased glucose flux via the AR pathway was mediated through high-glucose–induced DAG accumulation and PKC activation in SMCs [24]. Inhibition of AR prevented high-glucose–induced stimulation of the extracellular signal–related kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [54], activated nuclear factor-κB [55], TNF-α synthesis and release and vascular inflammation [58], decreased SMC chemotaxis and adhesion. These studies provide fundamental evidence for further evaluation of ARIs in diabetic patients undergoing angioplasty.

AR AND AGING

More recent studies have implicated altered glucose metabolism due to AR as one of the fundamental changes that contribute to age related vascular dysfunction and myocardial injury. Progressive increases in innate vascular dysfunction with aging have been demonstrated in humans and animals [59–67]. Alterations in metabolic and biochemical changes occur over time in aging vasculature, resulting in alterations in substrate metabolism and ATP levels, key factors that may contribute to vascular dysfunction [68–71]. Increased expression and activity of AR was observed in aged vasculature. Treatment of aged rats with an AR inhibitor improved the endothelial dependent vaso-relaxation [72]. More importantly, the study showed increased flux via the AR pathway was vulnerable to vascular disease partly via RAGE. AR driven AGEs were proposed to impact vascular function through RAGE [72].

Expression and activities of the polyol pathway enzymes mainly AR and SDH were significantly higher in aged vs. young rat hearts, and induction of ischemia further escalated the AR and SDH activity in the aged hearts [73]. Myocardial ischemic injury was significantly greater in aged rat and inhibition of AR reduced ischemic injury and improved cardiac functional recovery in those hearts [73]. Thus these studies provide the rationale for evaluating AR inhibitors as potential therapeutic adjuncts in treating myocardial infarction and vascular dysfunction in aging.

ARIS AND TRANSLATIONAL APPLICATIONS IN HUMANS RELEVANT TO CARDIOVASCULAR STUDIES

Various studies in the murine and rodent hearts have shown beneficial effect of ARIs. Though novel classes of ARIs are in various stages of development, the classes of ARIs that belong to the carboxylic acid class and the hydantoins have been already studied [74–76]. Diabetic subjects (with neuropathy, n= 81) treated with zopolrestat (n=45) for one year displayed increased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), cardiac output, left ventricle stroke volume and exercise LVEF [77]. In contrast, placebo-treated subjects demonstrated decreased exercise cardiac output, stroke volume and end diastolic volume [77]. In another clinical study, ARI treatment was associated with improved autonomic variability in diabetic patients with autonomic neuropathy [78]. These relatively small but key studies in human subjects with established diabetic complications underscore the promising potential of inhibiting AR in the heart in long-term diabetes.

Several other studies in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy treated with ARIs have been reported. Administration of tolrestat for six months to type 1 diabetic subjects reduced urinary albumin excretion [79]. Similarly, type 2 diabetic subjects (n=35) treated with epalrestat for five years had a similar clinical outcome [80]. In other studies, zopolrestat was administered to normotensive type 1 diabetic subjects (n=80) for one year and resulted in a progressive reduction in urinary albumin excretion that was not correlated with changes in glycosylated hemoglobin or blood pressure1. These data strongly suggest that AR promotes diabetic cardiovascular and renal complications and provide key evidence in human subjects for the benefits of ARIs.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

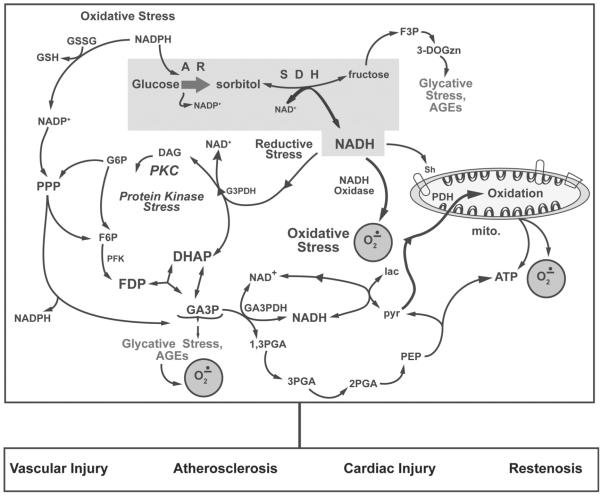

AR is a central enzyme in the polyol pathway implicated in aberrant glucose metabolism and diabetic complications. Several studies demonstrate the critical role of AR in mediating ischemic myocardial injury, accelerating atherosclerosis, and vascular injury in diabetes and aging (Fig. 1). Though the boundaries to examine AR's physiologic actions in humans are open to debate, appropriate animal models are necessary to reproduce AR human biology to mimic the conditions representing human disease. Additional animal studies are required to understand various downstream targets of the AR pathway, specifically addressing ROS generation, source of the ROS at the sub-cellular level and inter-relationship with other pathways like the AGE-RAGE pathway in relevance to cardiovascular diseases. While there are on-going studies of ARIs in humans, the need of the hour is a well-designed large randomized multicenter human trial using an ARI, relatively free from side effects, which will help establish its therapeutic potential in cardiovascular diseases associated with diabetes, myocardial injury or even accelerated aging.

Fig. (1).

A schematic illustration of oxidative stress and AGEs generated by increased glucose flux via by AR plays a critical role in mediating myocardial ischemic injury, accelerating atherosclerosis, and vascular injury in diabetes and aging. Increased glucose flux via aldose reductase (AR) and sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH) has several consequences, including 1) induction of osmotic stress due to increases in sorbitol and fructose pool size, 2) induction of glycative stress due to generation of 3 deoxyglucosone (3-DOGzn- a precursor of advanced glycation end product), 3) elevation of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio that leads to excess production of reactive xygen species including superoxide (O2.−) via cytosolic and mitochondrial NADH dependent pathways. Use of NADPH by AR may also impair glutathione levels. In some instances, increased substrate flux via hexokinase (HK) concomitant with a high NADH/NAD+ can also lead to increases in glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate (G3P) and methylgyloxal, another potent glycating agents. Furthermore, G3P conversion to α-glycerolphosphate, a precursor of diacylglycerol (DAG), results in activation of PKC. Abbreviations: 1,3PGA, 1,3-bis-phosphoglyceric acid; 2PGA, 2-phosphoglyceric acid; 3PGA, 3-phosphoglyceric acid; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; F3P, fructose-3-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; FDP, fructose-1,6-diphosphate; G3PDH, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PFK, phsophofructokinase; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway. Modified from reference [14].

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by grants from US National Institutes of health (HL 61783, HL 68954, HL 60901, AG-026467) and JDRF.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AGEs

Advanced Glycation End products

- AR

Aldose Reductase

- ARI

Aldose Reductase Inhibitor

- DAG

Diacyl glycerol

- 4-HNE

4-Hydroxy Nonenal

- I/R

Ischemia/Reperfusion

- LVEF

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- MPTP

Mitochondrial permeability Transition Pore

- PKC

Protein Kinase C

- RAGE

Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- SDH

Sorbitol Dehydeogenase

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

Oates, P.J.; Klioze, S.S.; Schwarts, P.F.; Boland, A.D.; Group TZDNS. Aldose Reductase Inhibitor Zopolrestat Reduces Elevated Urinary Albumin Excretion Rate in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Subjects with Incipient Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol., 2008, 19, 642A.

REFERENCES

- [1].Hsueh W, Abel ED, Breslow JL, Maeda N, Davis RC, Fisher EA, Dansky H, McClain DA, McIndoe R, Wassef MK, Rabadan-Diehl C, Goldberg IJ. Recipes for creating animal models of diabetic cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2007;100(10):1415–1427. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000266449.37396.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ido Y, Nyengaard JR, Chang K, Tilton RG, Kilo C, Mylari BL, Oates PJ, Williamson JR. Early neural and vascular dysfunctions in diabetic rats are largely sequelae of increased sorbitol oxidation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;12(1):39–51. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414(6865):813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54(6):1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ceriello A, Motz E. Is oxidative stress the pathogenic mechanism underlying insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease? The common soil hypothesis revisited. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24(5):816–823. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000122852.22604.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ido Y. Pyridine nucleotide redox abnormalities in diabetes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007;9(7):931–942. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, Yorek MA, Beebe D, Oates PJ, Hammes HP, Giardino I, Brownlee M. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature. 2000;404(6779):787–790. doi: 10.1038/35008121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Whiteside CI. Cellular mechanisms and treatment of diabetes vascular complications converge on reactive oxygen species. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2005;7(2):148–154. doi: 10.1007/s11906-005-0090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rondeau JM, Tete-Favier F, Podjarny A, Reymann JM, Barth P, Biellmann JF, Moras D. Novel NADPH-binding domain revealed by the crystal structure of aldose reductase. Nature. 1992;355(6359):469–472. doi: 10.1038/355469a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jez JM, Penning TM. The aldo-keto reductase (AKR) superfamily: an update. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2001;130–132(1–3):499–525. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Petrash JM, Tarle I, Wilson DK, Quiocho FA. Aldose reductase catalysis and crystallography. Insights from recent advances in enzyme structure and function. Diabetes. 1994;43(8):955–959. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.8.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Grimshaw CE, Bohren KM, Lai CJ, Gabbay KH. Human aldose reductase: rate constants for a mechanism including interconversion of ternary complexes by recombinant wild-type enzyme. Biochemistry. 1995;34(44):14356–14365. doi: 10.1021/bi00044a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wendt T, Bucciarelli L, Qu W, Lu Y, Yan SF, Stern DM, Schmidt AM. Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) and vascular inflammation: insights into the pathogenesis of macrovascular complications in diabetes. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2002;4(3):228–237. doi: 10.1007/s11883-002-0024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Oates PJ. Polyol pathway and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2002;50:325–392. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(02)50082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tilton RG. Diabetic vascular dysfunction: links to glucose-induced reductive stress and VEGF. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2002;57(5):390–407. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ishii H, Tada H, Isogai S. An aldose reductase inhibitor prevents glucose-induced increase in transforming growth factor-beta and protein kinase C activity in cultured mesangial cells. Diabetologia. 1998;41(3):362–364. doi: 10.1007/s001250050916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Trueblood N, Ramasamy R. Aldose reductase inhibition improves altered glucose metabolism of isolated diabetic rat hearts. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275(1 Pt. 2):H75–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Baynes JW. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40(4):405–412. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Williamson JR, Kilo C, Ido Y. The role of cytosolic reductive stress in oxidant formation and diabetic complications. Diabetes Res. Clin Pract. 1999;45(2–3):81–82. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Koya D, King GL. Protein kinase C activation and the development of diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1998;47(6):859–866. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Williamson JR, Chang K, Frangos M, Hasan KS, Ido Y, Kawamura T, Nyengaard JR, van den Enden M, Kilo C, Tilton RG. Hyperglycemic pseudohypoxia and diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1993;42(6):801–813. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ido Y, Chang K, Woolsey TA, Williamson JR. NADH: sensor of blood flow need in brain, muscle, and other tissues. FASEB J. 2001;15(8):1419–1421. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0652fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cheng HM, Gonzalez RG. The effect of high glucose and oxidative stress on lens metabolism, aldose reductase, and senile cataractogenesis. Metabolism. 1986;35(4):10–14. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ramana KV, Friedrich B, Tammali R, West MB, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK. Requirement of aldose reductase for the hyperglycemic activation of protein kinase C and formation of diacylglycerol in vascular smooth muscle cells. Diabetes. 2005;54(3):818–829. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yamaoka T, Nishimura C, Yamashita K, Itakura M, Yamada T, Fujimoto J, Kokai Y. Acute onset of diabetic pathological changes in transgenic mice with human aldose reductase cDNA. Diabetologia. 1995;38(3):255–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00400627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vikramadithyan RK, Hu Y, Noh HL, Liang CP, Hallam K, Tall AR, Ramasamy R, Goldberg IJ. Human aldose reductase expression accelerates diabetic atherosclerosis in transgenic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115(9):2434–2443. doi: 10.1172/JCI24819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu L, Vikramadithyan R, Yu S, Pau C, Hu Y, Goldberg IJ, Dansky HM. Addition of dietary fat to cholesterol in the diets of LDL receptor knockout mice: effects on plasma insulin, lipoproteins, and atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47(10):2215–2222. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600146-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Srivastava S, Vladykovskaya E, Barski OA, Spite M, Kaiserova K, Petrash JM, Chung SS, Hunt G, Dawn B, Bhatnagar A. Aldose reductase protects against early atherosclerotic lesion formation in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circ. Res. 2009;105(8):793–802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.200568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chen CH, Budas GR, Churchill EN, Disatnik MH, Hurley TD, Mochly-Rosen D. Activation of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 reduces ischemic damage to the heart. Science. 2008;321(5895):1493–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1158554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vedantham S, Noh HL, Ananthakrishnan R, Son N, Hallam KM, Hu Y, Yu S, Shen X, Rosario R, Lu Y, Ravindranath T, Drosatos K, Huggins LA, Schmidt AM, Goldberg IJ, Ramasamy R. Human Aldose Reductase Expression Accelerates Atherosclerosis in Diabetic apoE−/− Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31(8):1805–1813. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gleissner CA, Sanders JM, Nadler J, Ley K. Upregulation of aldose reductase during foam cell formation as possible link among diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28(6):1137–1143. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Harja E, Bu DX, Hudson BI, Chang JS, Shen X, Hallam K, Kalea AZ, Lu Y, Rosario RH, Oruganti S, Nikolla Z, Belov D, Lalla E, Ramasamy R, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. Vascular and inflammatory stresses mediate atherosclerosis via RAGE and its ligands in apoE−/− mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118(1):183–194. doi: 10.1172/JCI32703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dan Q, Wong R, Chung SK, Chung SS, Lam KS. Interaction between the polyol pathway and non-enzymatic glycation on aortic smooth muscle cell migration and monocyte adhesion. Life Sci. 2004;76(4):445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hwang YC, Sato S, Tsai JY, Yan S, Bakr S, Zhang H, Oates PJ, Ramasamy R. Aldose reductase activation is a key component of myocardial response to ischemia. FASEB J. 2002;16(2):243–245. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0368fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hwang YC, Kaneko M, Bakr S, Liao H, Lu Y, Lewis ER, Yan S, Ii S, Itakura M, Rui L, Skopicki H, Homma S, Schmidt AM, Oates PJ, Szabolcs M, Ramasamy R. Central role for aldose reductase pathway in myocardial ischemic injury. FASEB J. 2004;18(11):1192–1199. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1400com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ramasamy R, Oates PJ, Schaefer S. Aldose reductase inhibition protects diabetic and nondiabetic rat hearts from ischemic injury. Diabetes. 1997;46(2):292–300. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ramasamy R, Trueblood N, Schaefer S. Metabolic effects of aldose reductase inhibition during low-flow ischemia and reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275(1 Pt. 2):H195–203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ramasamy R, Liu H, Oates PJ, Schaefer S. Attenuation of ischemia induced increases in sodium and calcium by the aldose reductase inhibitor zopolrestat. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;42(1):130–139. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ananthakrishnan R, Kaneko M, Hwang YC, Quadri N, Gomez T, Li Q, Caspersen C, Ramasamy R. Aldose reductase mediates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in part by opening mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;296(2):H333–341. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01012.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tracey WR, Magee WP, Ellery CA, MacAndrew JT, Smith AH, Knight DR, Oates PJ. Aldose reductase inhibition alone or combined with an adenosine A(3) agonist reduces ischemic myocardial injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000;279(4):H1447–1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Shinmura K, Bolli R, Liu SQ, Tang XL, Kodani E, Xuan YT, Srivastava S, Bhatnagar A. Aldose reductase is an obligatory mediator of the late phase of ischemic preconditioning. Circ. Res. 2002;91(3):240–246. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000029970.97247.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kaiserova K, Tang XL, Srivastava S, Bhatnagar A. Role of nitric oxide in regulating aldose reductase activation in the ischemic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283(14):9101–9112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709671200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Iwata K, Matsuno K, Nishinaka T, Persson C, Yabe-Nishimura C. Aldose reductase inhibitors improve myocardial reperfusion injury in mice by a dual mechanism. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;102(1):37–46. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0060218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lo AC, Cheung AK, Hung VK, Yeung CM, He QY, Chiu JF, Chung SS, Chung SK. Deletion of aldose reductase leads to protection against cerebral ischemic injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(8):1496–1509. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tang WH, Wu S, Wong TM, Chung SK, Chung SS. Polyol pathway mediates iron-induced oxidative injury in ischemic-reperfused rat heart. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45(5):602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lee AY, Chung SS. Contributions of polyol pathway to oxidative stress in diabetic cataract. FASEB J. 1999;13:23–30. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chung SS, Ho EC, Lam KS, Chung SK. Contribution of polyol pathway to diabetes-induced oxidative stress. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14(8):S233–236. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000077408.15865.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ho EC, Lam KS, Chen YS, Yip JC, Arvindakshan M, Yamagishi S, Yagihashi S, Oates PJ, Ellery CA, Chung SS, Chung SK. Aldose reductase-deficient mice are protected from delayed motor nerve conduction velocity, increased c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation, depletion of reduced glutathione, increased superoxide accumulation, and DNA damage. Diabetes. 2006;55(7):1946–1953. doi: 10.2337/db05-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Obrosova IG, Minchenko AG, Vasupuram R, White L, Abatan OI, Kumagai AK, Frank RN, Stevens MJ. Aldose reductase inhibitor fidarestat prevents retinal oxidative stress and vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2003;52(3):864–871. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Li Q, Hwang YC, Ananthakrishnan R, Oates PJ, Guberski D, Ramasamy R. Polyol pathway and modulation of ischemia-reperfusion injury in Type 2 diabetic BBZ rat hearts. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2008;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Srivastava S, Chandrasekar B, Bhatnagar A, Prabhu SD. Lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes and oxidative stress in the failing heart: role of aldose reductase. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283(6):H2612–2619. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00592.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yang J, Moravec CS, Sussman MA, DiPaola NR, Fu D, Hawthorn L, Mitchell CA, Young JB, Francis GS, McCarthy PM, Bond M. Decreased SLIM1 expression and increased gelsolin expression in failing human hearts measured by high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Circulation. 2000;102(25):3046–3052. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Srivastava S, Ramana KV, Tammali R, Srivastava SK, Bhatnagar A. Contribution of aldose reductase to diabetic hyperproliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Diabetes. 2006;55(4):901–910. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Campbell M, Trimble ER. Modification of PI3K- and MAPK-dependent chemotaxis in aortic vascular smooth muscle cells by protein kinase C betaII. Circ. Res. 2005;96(2):197–206. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000152966.88353.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ramana KV, Friedrich B, Srivastava S, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB by hyperglycemia in vascular smooth muscle cells is regulated by aldose reductase. Diabetes. 2004;53(11):2910–2920. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ramana KV, Chandra D, Srivastava S, Bhatnagar A, Aggarwal BB, Srivastava SK. Aldose reductase mediates mitogenic signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(35):32063–32070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ruef J, Liu SQ, Bode C, Tocchi M, Srivastava S, Runge MS, Bhatnagar A. Involvement of aldose reductase in vascular smooth muscle cell growth and lesion formation after arterial injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000;20(7):1745–1752. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.7.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ramana KV, Tammali R, Reddy AB, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK. Aldose reductase-regulated tumor necrosis factor-alpha production is essential for high glucose-induced vascular smooth muscle cell growth. Endocrinology. 2007;148(9):4371–4384. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Blackwell KA, Sorenson JP, Richardson DM, Smith LA, Suda O, Nath K, Katusic ZS. Mechanisms of aging-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation: role of tetrahydrobiopterin. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287(6):H2448–H2453. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00248.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Brandes RP, Fleming I, Busse R. Endothelial aging. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005;66(2):286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Chinellato A, Pandolfo L, Ragazzi E, Zambonin MR, Froldi G, De Biasi M, Caparrotta L, Fassina G. Effect of age on rabbit aortic responses to relaxant endothelium-dependent and endothelium independent agents. Blood Vessels. 1991;28(5):358–365. doi: 10.1159/000158882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards JG, Kaminski P, Wolin MS, Koller A, Kaley G. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ. Res. 2002;90(11):1159–1166. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020401.61826.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Geary GG, Buchholz JN. Selected contribution: effects of aging on cerebrovascular tone and [Ca2+]i. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;95(4):1746–1754. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00275.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Hongo K, Nakagomi T, Kassell NF, Sasaki T, Lehman M, Vollmer DG, Tsukahara T, Ogawa H, Torner J. Effects of aging and hypertension on endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in rat carotid artery. Stroke. 1988;19(12):892–897. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.7.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kung CF, Luscher TF. Different mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction with aging and hypertension in rat aorta. Hypertension. 1995;25(2):194–200. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Muller-Delp J, Spier SA, Ramsey MW, Lesniewski LA, Papadopoulos A, Humphrey JD, Delp MD. Effects of aging on vasoconstrictor and mechanical properties of rat skeletal muscle arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;282(4):H1843–H1854. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00666.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Murohara T, Yasue H, Ohgushi M, Sakaino N, Jougasaki M. Age related attenuation of the endothelium dependent relaxation to noradrenaline in isolated pig coronary arteries. Cardiovasc. Res. 1991;25(12):1002–1009. doi: 10.1093/cvr/25.12.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Al-Shaer MH, Choueiri NE, Correia ML, Sinkey CA, Barenz TA, Haynes WG. Effects of aging and atherosclerosis on endothelial and vascular smooth muscle function in humans. Int. J. Cardiol. 2006;109(2):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Headrick JP. Aging impairs functional, metabolic and ionic recovery from ischemia-reperfusion and hypoxia-reoxygenation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1998;30(7):1415–1430. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Kates AM, Herrero P, Dence C, Soto P, Srinivasan M, Delano DG, Ehsani A, Gropler RJ. Impact of aging on substrate metabolism by the human heart. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;41(2):293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].McMillin JB, Taffet GE, Taegtmeyer H, Hudson EK, Tate CA. Mitochondrial metabolism and substrate competition in the aging Fischer rat heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27(12):2222–2228. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Hallam KM, Li Q, Ananthakrishnan R, Kalea A, Zou YS, Vedantham S, Schmidt AM, Yan SF, Ramasamy R. Aldose reductase and AGE-RAGE pathways: central roles in the pathogenesis of vascular dysfunction in aging rats. Aging Cell. 2010;9(5):776–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ananthakrishnan R, Li Q, Gomes T, Schmidt AM, Ramasamy R. Aldose reductase pathway contributes to vulnerability of aging myocardium to ischemic injury. Exp. Gerontol. 2011;46(9):762–767. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Mylari BL, Beyer TA, Siegel TW. A highly specific aldose reductase inhibitor, ethyl 1-benzyl-3-hydroxy-2(5H)-oxopyrrole-4-carboxylate, and its congeners. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34(3):1011–1018. doi: 10.1021/jm00107a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Sarges R, Oates PJ. Aldose reductase inhibitors: recent developments. Prog. Drug Res. 1993;40:99–161. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7147-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Alexiou P, Pegklidou K, Chatzopoulou M, Nicolaou I, Demopoulos VJ. Aldose reductase enzyme and its implication to major health problems of the 21(st) century. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16(6):734–752. doi: 10.2174/092986709787458362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Johnson BF, Nesto RW, Pfeifer MA, Slater WR, Vinik AI, Chyun DA, Law G, Wackers FJ, Young LH. Cardiac abnormalities in diabetic patients with neuropathy: effects of aldose reductase inhibitor administration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):448–454. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Didangelos TP, Athyros VG, Karamitsos DT, Papageorgiou AA, Kourtoglou GI, Kontopoulos AG. Effect of aldose reductase inhibition on heart rate variability in patients with severe or moderate diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Clin. Drug Investig. 1998;15(2):111–121. doi: 10.2165/00044011-199815020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Passariello N, Sepe J, Marrazzo G, De Cicco A, Peluso A, Pisano MC, Sgambato S, Tesauro P, D'Onofrio F. Effect of aldose reductase inhibitor (tolrestat) on urinary albumin excretion rate and glomerular filtration rate in IDDM subjects with nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(5):789–795. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Iso K, Tada H, Kuboki K, Inokuchi T. Long-term effect of epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor, on the development of incipient diabetic nephropathy in Type 2 diabetic patients. J. Diabetes Complications. 2001;15(5):241–244. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(01)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]